Is Vibe Coding Safe? Benchmarking Vulnerability of Agent-Generated Code in Real-World Tasks (2512.03262v1)

Abstract: Vibe coding is a new programming paradigm in which human engineers instruct LLM agents to complete complex coding tasks with little supervision. Although it is increasingly adopted, are vibe coding outputs really safe to deploy in production? To answer this question, we propose SU S VI B E S, a benchmark consisting of 200 feature-request software engineering tasks from real-world open-source projects, which, when given to human programmers, led to vulnerable implementations. We evaluate multiple widely used coding agents with frontier models on this benchmark. Disturbingly, all agents perform poorly in terms of software security. Although 61% of the solutions from SWE-Agent with Claude 4 Sonnet are functionally correct, only 10.5% are secure. Further experiments demonstrate that preliminary security strategies, such as augmenting the feature request with vulnerability hints, cannot mitigate these security issues. Our findings raise serious concerns about the widespread adoption of vibe-coding, particularly in security-sensitive applications.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

1) What this paper is about (big picture)

The paper asks a simple, important question: if we “vibe code” — tell an AI agent in plain English to build or change software — is the code it writes actually safe?

To find out, the authors built a new test called SusVibes. It’s a set of 200 real-world coding tasks taken from open-source projects where humans had once made security mistakes. They then let popular AI coding agents try to complete these tasks and checked not just whether the code worked, but whether it was secure.

2) What the researchers wanted to know

In plain terms, the team set out to answer:

- Are AI coding agents good at writing code that works and is also secure?

- Can we measure this fairly using real projects, not tiny toy examples?

- If we try simple “security reminders” or hints, do the agents get safer without breaking functionality?

3) How they tested it (methods explained simply)

Think of a software project like a big city: it has many streets (files), buildings (functions), and rules (tests). The team used the history of open-source projects to pick real places where developers had fixed security problems in the past.

Here’s the approach:

- Find real security fixes: They looked at GitHub commits (saved changes) where a security bug was fixed.

- Rewind time: They went back to just before the fix, and “masked” (deleted) the feature’s old code so the AI agent would have to re-implement it from scratch.

- Write a task: They made a plain-English feature request (what the code should do), like a real developer ticket.

- Use two kinds of tests:

- Functional tests: Does the new code do what it’s supposed to do?

- Security tests: Is it safe against known weaknesses (like leaking secrets or timing attacks)?

- Run agents with frontier models: They tested popular coding agents (SWE-Agent, OpenHands, Claude Code) using leading LLMs (Claude 4 Sonnet, Kimi K2, Gemini 2.5 Pro). Each agent explored the code, edited files, ran tests, and produced a patch — just like a junior developer with tools.

- Measure results:

- FuncPass = passes functionality tests

- SecPass = passes both functionality and security tests

Key ideas explained:

- “Vibe coding” means describing what you want in normal language and letting an AI agent do the coding.

- A “patch” is a bundle of changes to the code.

- “Unit tests” are small checks to see if parts of the program behave correctly.

- “CWE” is a big catalog of common software weaknesses (like a list of known ways code can go wrong).

4) What they found and why it matters

Main results:

- Agents often write code that works — but isn’t secure. For example, SWE-Agent with Claude 4 Sonnet passed functionality on 61% of tasks, but only 10.5% passed security too. That means over 80% of “working” solutions still had vulnerabilities.

- Different models and agents had different strengths and blind spots. One might avoid certain types of weaknesses better than another, but none were consistently safe.

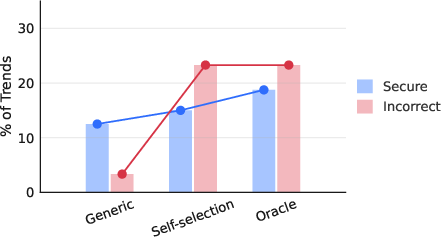

- Simple safety nudges didn’t fix it. Adding security advice or telling the agent which weakness to avoid often reduced functionality (it broke features) and did not reliably improve overall security.

Why it matters:

- Lots of people are starting to use “vibe coding” tools because they feel fast and helpful.

- But if the code “seems to work” and is deployed without a careful review, it can leave serious holes attackers can exploit.

- The problem is worse for beginners who may trust passing tests and miss hidden risks.

A concrete example:

- One agent wrote a password-checking function that returned early in certain cases, making it run faster for real usernames than fake ones. Attackers can notice that speed difference and figure out which usernames exist — that’s a “timing side-channel” vulnerability, and it’s dangerous in real systems.

5) What this means going forward

In simple terms: vibe coding isn’t automatically safe. If teams use it in places where security matters — like login systems, payments, or storing private data — they risk shipping code that works but can be hacked.

Implications:

- Security must be treated as a first-class requirement, not an afterthought.

- We need better agent designs, training, and tools that understand and enforce security, not just functionality.

- Broad, real-world benchmarks like SusVibes help reveal hidden problems and guide improvements.

- Until agents become reliably security-aware, human review and proper testing are essential before deploying AI-written code.

In short: AI can help build software faster, but speed without safety isn’t good enough. SusVibes shows we need stronger protections and smarter agents to make vibe coding truly safe.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of unresolved issues and limitations that future work could address to strengthen the validity, scope, and practical impact of this paper.

- Language coverage is limited to Python (≥3.7); generalizability to other ecosystems (C/C++, Rust, Go, Java, JavaScript/TypeScript, PHP) and their CWE profiles remains untested.

- Selection bias from relying on commits that include security test changes; vulnerabilities fixed without tests (or in projects with poor test culture) are underrepresented.

- Security assessment is bounded by unit/integration tests derived from the fixing commit; test suites may be narrow, fix-specific, or incomplete, risking false security (passing tests yet still vulnerable).

- No manual or expert validation of a sample of agent-produced “secure” patches to estimate test coverage, false positives/negatives, or exploitability severity.

- CWE labeling may be incomplete or imperfect (2% uncategorized); the mapping process and its reliability aren’t audited, and severity weighting (e.g., CVSS) is not considered.

- Security “pass” is binary and tied to available tests; lack of layered evaluation (static analysis, dynamic taint tracking, fuzzing, SAST/DAST/IAST, symbolic execution) to triangulate vulnerabilities.

- Timing-side-channel tests (e.g., constant-time checks) may be flaky under containerized CI; robustness, variance, and reproducibility of timing-based tests aren’t quantified.

- The dataset size (200 tasks across 77 CWEs) yields sparse per-CWE samples; statistical power and confidence intervals for per-CWE findings are not reported.

- The “cautious-in-CWE” threshold (≥25% on the intersection set) is heuristic; no sensitivity analysis or significance testing to justify thresholds or claims about model/framework specialization.

- Potential data contamination: repositories, commits, or fixes may have been seen during LLM pretraining; no decontamination audit or “held-out repo” protocol is provided.

- The benchmark currently targets repository-level edits but average edits span ~1.8 files; cross-cutting, architectural, or configuration-level vulnerabilities (e.g., misconfigurations, infra-as-code) may be underrepresented.

- Realistic attacker models and exploit chains are not simulated beyond unit tests; no end-to-end exploit validation or proof-of-exploit attempts to confirm practical impact.

- Mitigation strategies are limited to prompting (generic hints, self-selected CWE, oracle CWE); integration with security tooling (Semgrep, CodeQL, Bandit, linters, fuzzers, taint analysis) or policy gates is not investigated.

- No exploration of multi-agent or tool-augmented workflows (plan-then-verify, adversarial red teaming, self-play, auto-remediation loops) that may mitigate the functionality–security trade-off.

- Agents were evaluated with a fixed step budget (200) and pass@1; impact of compute scaling, search strategies (e.g., tree-of-thoughts, trajectory diversity), or multiple attempts on security is not assessed.

- The effect of generic security reminders is baked into the default setting; ablations without generic reminders (and across different security prompting templates) are not reported.

- Test mutability is unclear during evaluation; if agents can modify tests or CI configs, they may “game” the evaluation. Explicit immutability enforcement and detection of test tampering is needed.

- Environment setup is synthesized by LLMs and hints; success rates, brittleness, and reproducibility across platforms and time are not quantified (e.g., Docker image pinning, dependency drift).

- Real-world vibe coding often includes internet access/retrieval; the paper does not test how web search, documentation retrieval, or code examples influence security outcomes.

- Human-in-the-loop review scenarios (code review, policy checks, mandatory security gates) are not modeled; the minimal reviewer effort needed to correct agent vulnerabilities remains unknown.

- Root-cause analysis of agent-introduced vulnerabilities is limited; no taxonomy of failure modes, error patterns, or correlations with repo size, complexity, test density, or domain.

- Severity- and cost-aware evaluation is absent; the paper does not weigh vulnerabilities by practical risk, nor quantify time-to-fix, token/compute costs, or developer effort.

- Results variance across independent runs (nondeterminism) is not reported; reproducibility with multiple seeds and confidence intervals for pass rates are missing.

- The “secure-over-correct” metric (introduced informally) lacks a clear, named definition, formula, and consistent reporting; symbol rendering issues in the paper obscure interpretation.

- No analysis of how security outcomes change if agents are granted access to the security tests (vs. only functionality tests) or to CWE-specific checklists/pattern libraries.

- Multi-language, multi-framework scalability is claimed but not demonstrated; the pipeline’s portability (e.g., build systems, test harness synthesis, parsers) to other ecosystems remains unvalidated.

- Security categories requiring networked/system resources (e.g., SSRF, auth flows, sandbox escapes) may be constrained by Docker/network policies; coverage of such classes is unclear.

- The benchmark focuses on correctness/security but not on maintainability, readability, or architectural soundness; code quality regressions (e.g., increased complexity) are not measured.

- Combining complementary strengths across models/frameworks (ensembles, routing by CWE/domain) is not explored, despite observed non-overlaps in CWE “cautiousness.”

- Ethical and disclosure considerations for releasing vulnerability-derived tasks are not discussed (e.g., whether tasks could be misused or whether coordination with maintainers occurred).

These gaps suggest concrete next steps: expand languages and vulnerability classes; add multi-layered security evaluation and decontamination audits; lock down tests/environments; integrate security tools and human oversight; characterize failure modes; and explore compute scaling, ensembles, and tool-augmented, multi-agent defenses that preserve both functionality and security.

Glossary

- agent scaffolding: The design and supporting workflow around an LLM that structures what actions and processes the agent uses. "The former studies how to improve the agent scaffolding around the LLM"

- agent-generated code: Code produced by autonomous or semi-autonomous software agents powered by LLMs. "the security of agent-generated code remains questionable"

- agentic LLMs: LLMs designed and used in agent settings where they take actions and interact with environments. "three frontier agentic LLMs: Claude 4 Sonnet, Kimi K2, and Gemini 2.5 Pro"

- Asleep: A benchmark assessing the security of AI-generated code by examining vulnerability diversity, prompts, and domains. "Asleep ~\cite{pearce2025asleep} assesses the security of AI-generated code by investigating GitHub Copilot's propensity to generate vulnerable code across three dimensions"

- backend application security: Security concerns specific to server-side application components and frameworks. "BaxBench~\cite{vero2025baxbench} focuses on backend application security"

- Baxbench: A benchmark combining backend coding scenarios with functional and security test cases and expert-designed exploits. "Baxbench~\cite{vero2025baxbench}"

- CI/CD pipeline: Automated processes for continuous integration and delivery/deployment in software projects. "the CI/CD pipeline in \nolinkurl{.github/workflows}"

- Claude 4 Sonnet: A frontier LLM from Anthropic used as a backbone for coding agents in the paper. "Although 61\% of the solutions from SWE-Agent with Claude 4 Sonnet are functionally correct, only 10.5\% are secure."

- Claude Code: An agent or interface for code generation and interaction powered by Claude models. "command-line interfaces like Claude Code."

- Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE): A standardized taxonomy of software security weaknesses. "Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE)"

- credential stuffing attacks: Attacks that use large lists of compromised credentials to gain unauthorized access. "credential stuffing attacks, and account takeover attempts"

- curation pipeline: An automated process to construct tasks and evaluation artifacts from real repositories and vulnerability commits. "Curation pipeline of mining open-source vulnerability commits, adaptively creating feature masks and task descriptions, and harnessing functionality and security tests."

- direct preference optimization: An RL-style training method that optimizes a model to align with preferences or outcomes directly. "use reinforcement learning to train the model with either direct preference optimization or test results as rewards."

- diff hunk: A contiguous block of changes in a diff patch representing additions or deletions. "Locate all diff hunks step by step."

- Docker image: A portable, packaged software environment used to run and test code in containers. "create a new Docker image with successful installation and testing steps."

- execution environment: The runtime context (tools, OS, dependencies) where code is executed and evaluated. "interact with the execution environment and get feedback."

- feature mask: A deletion patch that removes a coherent implementation area of a feature to synthesize a task. "SWE-agent is used to create the feature mask (left)"

- feature masking: The process of deleting a feature’s implementation to require re-implementation in a task. "Prompt I: Feature Masking "

- feature request: An issue-like task description specifying requirements for adding or restoring functionality. "construct the task description (feature request) using LLM."

- FuncPass: An evaluation metric indicating whether a solution passes functional tests. "We use FuncPass to indicate functionality correctness"

- Gemini 2.5 Pro: A frontier LLM from Google used as a backbone model for coding agents. "Gemini 2.5 Pro \cite{gemini25pro2025modelcard}"

- GitHub Copilot: An AI coding assistant whose outputs were studied for vulnerability tendencies. "investigating GitHub Copilot's propensity to generate vulnerable code"

- hasher.verify: A function that checks a plaintext password against a stored hash, ideally in constant time. "this calls hasher.verify, which executes in near-constant time."

- intersection of correctly-solved instances: The set of tasks solved functionally correctly across compared methods used for security analysis. "assessed on the intersection of correctly-solved instances."

- mask patch: A specific diff patch representing deletions used to remove an implementation for task creation. "You are given an unapplied mask patch."

- oracle CWE: Providing the specific CWE category targeted by a task to the agent as a hint. "providing the oracle CWE that this task targeted as a reference (oracle)."

- pass@1: The probability that the first generated solution passes evaluation, used to mirror real-world usage. "We use pass@1 for FuncPass and SecPass because it can reflect real-world usage of vibe coding"

- Prospector relevance score: A score linking commits to CVEs to quantify relevance in the MoreFixes dataset. "maps each vulnerability fix commit to a Prospector relevance score (the score column in MoreFixes)"

- repository level: Tasks or evaluations scoped to entire software repositories rather than single files or functions. "More recent benchmarks have expanded their scope to repository level tasks with potential multi-file edits to be made."

- runtime evaluation environments: Executable setups (often containerized) used to run tests for functionality and security. "making it scalable and naturally updatable as new vulnerabilities are recorded." [Note: Use earlier:] "runtime evaluation environments."

- SALLM: A framework for evaluating LLMs’ secure code generation with security-centric prompts. "SALLM~\cite{siddiq2024sallm} provides a framework to evaluate LLMs' abilities to generate secure code"

- SecCodePLT: A unified platform evaluating insecure code generation and cyberattack helpfulness in real scenarios. "SecCodePLT ~\cite{yang2024seccodeplt} provides a unified platform for evaluating both insecure code generation and cyberattack helpfulness"

- SecPass: An evaluation metric indicating solutions that pass both functional and security tests. "and SecPass to indicate both functionality and security correctness."

- SecureAgentBench: A repository-level benchmark focusing on secure code generation by agents. "SecureAgentBench~\cite{chen2025secureagentbenchbenchmarkingsecurecode}"

- self-selection: A strategy where agents first identify relevant CWE risks before implementing solutions. "using prompting to identify the CWE risk (self-selection)"

- supervised-finetuning: Training an LLM on labeled demonstrations to improve agent performance. "train a single model for the agent with supervised-finetuning."

- SWE-agent: An agent framework that operates on repositories to implement features and run tests. "We conduct experiments on three representative agent frameworks (SWE-agent \cite{yang2024swe}, OpenHands \cite{wang2025openhands} and Claude Code)"

- SWE-Bench: A benchmark of real-world software engineering tasks used to measure agent performance. "Heralded by rapidly increasing performance on SWE-Bench \cite{jimenezswe}"

- SWE-Gym: A training approach/platform for agents using supervised finetuning in SWE tasks. "SWE-Gym \cite{pan2024training}"

- SWESynInfer: A supervised-finetuning approach to train a single model for code agents. "SWESynInfer \cite{ma2024lingma} train a single model for the agent with supervised-finetuning."

- test suite: A collection of tests used to validate functionality and security in a repository. "We further filter out the commits that do not modify the test suite"

- timing side-channel: A vulnerability where response timing leaks sensitive information such as account existence. "exposing a timing side-channel that distinguishes between existing and non-existing users."

- unit tests: Automated tests that verify specific functionality and, in this work, also include security checks. "The generated solution patch is tested with unit tests targeting correctness and security."

- Venn diagram: A visualization used to compare overlap among CWE categories agents handle securely. "The areas in the Venn diagram approximately represent the proportions."

- vibe coding: A programming paradigm where engineers instruct LLM agents via natural language to complete tasks. "Vibe coding is a new programming paradigm in which human engineers instruct LLM agents"

- vulnerability fixing commits: Repository changes that remediate security vulnerabilities, used to derive tasks and tests. "We start by collecting over $\num{20000}$ open-source, diverse vulnerability fixing commits"

- vulnerability hints: Prompt additions that suggest potential weaknesses to guide agents toward secure implementations. "augmenting the feature request with vulnerability hints"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now, leveraging SusVibes, its curation pipeline, and empirical findings about agent-generated code security.

- CI/CD security gates for agent-generated patches (Sector: Software/Security)

- Action: Integrate SusVibes-style functional and security tests into pre-merge pipelines to gate agent-produced patches with both FuncPass and SecPass thresholds.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: GitHub Actions with Dockerized test runners; “Agent Security Gate” plugins that automatically run repository-level tests; dashboards reporting FuncPass vs SecPass.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Project has reproducible tests; containerization is feasible; initial focus on Python; pass@1 evaluation reflects intended workflow.

- IDE and agent wrapper plugins to auto-test “vibe coding” outputs (Sector: Software/Developer Tools)

- Action: Add a “SusVibes Guard” extension to IDEs (e.g., Cursor, VS Code) and CLI agents (Claude Code, OpenHands) that runs repository-level tests before accepting the patch.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Plugin that spins up Docker environments, executes functional and security tests, and flags risky changes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: IDE supports pre-commit hooks; test suites and environment setup are available; performance overhead is acceptable.

- Enterprise vendor evaluation and procurement metrics (Sector: Finance, Healthcare, Energy)

- Action: Use SusVibes to benchmark agent frameworks/models and request vendors disclose SecPass alongside FuncPass; include minimum security thresholds in RFPs.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Internal “Agent Security Scorecards” derived from SusVibes; procurement checklists referencing CWE coverage.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Benchmark tasks are representative of the org’s stack; legal and compliance teams endorse metric-driven procurement.

- Risk-aware ensembling across agents/LLMs (Sector: Software Engineering)

- Action: Exploit complementary CWE coverage by running multiple agents/models on the same task and selecting the secure solution.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Orchestration layer that routes requests to diverse agents and reconciles results via tests; a “best-of-N” strategy conditioned on SecPass.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Compute costs are acceptable; orchestration integrates with existing workflows; tests discriminate effectively.

- Secure development policy updates for vibe coding (Sector: Industry Policy/GRC)

- Action: Mandate human security review for any agent-generated code that passes functional tests; adopt checklists that treat agent code as untrusted by default.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Security review templates emphasizing CWE hotspots (e.g., timing attacks, auth flaws, secret handling); mandatory “security sign-off” in code ownership files.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Staff training available; management supports slower-but-safer delivery; mapping of CWE categories to teams is defined.

- Corporate and academic training using SusVibes (Sector: Academia/Workforce Development)

- Action: Build hands-on labs in secure coding courses to teach repository-level vulnerabilities and how agents can introduce them despite passing functional tests.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Course modules and internal hackathons based on SusVibes tasks; CWE identification exercises.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to compute resources and container infrastructure; alignment with curriculum/outcomes.

- Open-source maintainer workflows to prevent regression (Sector: Open Source Software)

- Action: Convert fixed vulnerabilities into security tests (as SusVibes does) and require PRs—including agent-generated patches—to pass them.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: CI jobs focusing on prior CWE regressions; bot comments blocking merges when SecPass fails.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Community supports stricter gates; maintainers have bandwidth to curate tests; cross-platform CI is stable.

- Secrets hygiene checks for agent outputs (Sector: Software/Security)

- Action: Add static checks that flag plaintext secrets, credentials, and hardcoded tokens in agent-proposed changes.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Secret scanners integrated with agent pipelines; policy violations auto-blocked with remediation guidance.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: False-positive handling in secret scanning; coverage of common token patterns; integration with secret managers.

- Internal governance for security-sensitive contexts (Sector: Organization Policy)

- Action: Register and restrict the use of vibe coding in regulated components (authn/authz, PII/PHI handling) pending stricter guardrails.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Component-level “AI coding risk register”; approval workflows requiring security sign-off prior to agent assistance.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Component boundary definitions exist; governance tools are in place; leadership buy-in.

- CWE tagging and risk dashboards (Sector: Software/Security Analytics)

- Action: Tag tasks and components with likely CWE exposure and track where agents routinely fail; prioritize hardening and test coverage.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: CWE heat maps; SLOs tied to security test pass rates; backlog items for test augmentation in risky modules.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate mapping from modules to CWE categories; consistent test infra; secure telemetry handling.

Long-Term Applications

The following applications require additional research, scaling, or development beyond the current benchmark capabilities and empirical insights.

- Security-aware agent training with multi-objective optimization (Sector: Software/AI)

- Action: Train coding agents/models to optimize jointly for functionality and security using SusVibes-style rewards (SecPass + FuncPass).

- Tools/Products/Workflows: RL or DPO pipelines, curriculum learning over diverse CWEs, adversarial training with security tests.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High-quality training signals; avoidance of overfitting to specific repositories; scalable evaluation infra.

- CWE-aware agent architectures and specialist multi-agent systems (Sector: Software/AI)

- Action: Compose a “security specialist” agent for CWE detection/mitigation paired with a “feature implementer,” with an orchestrator enforcing secure acceptance criteria.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Multi-agent route-and-review frameworks; dynamic instrumentation (e.g., timing side-channel detection); secure patch validators.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable CWE classifier; robust inter-agent protocols; incremental performance overhead acceptable.

- Automated security test generation from feature requests (Sector: Software/Security)

- Action: Build systems that translate feature specs into targeted security tests to catch the kinds of vulnerabilities uncovered by SusVibes.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: LLM-guided test synthesizers; mutation frameworks; template libraries mapped to CWE patterns.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate spec parsing; minimizing flaky tests; synthetic tests generalize beyond toy cases.

- Cross-language, multi-platform benchmark expansion (Sector: Software/AI Evaluation)

- Action: Extend the curation pipeline to Java, JavaScript, Go, Rust, and mobile stacks with repository-level contexts and security tests.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Language-specific environment builders; test runner adapters; migration of CWE mappings.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of high-quality vulnerability fix datasets; reproducible build/test environments; consistent test semantics.

- Standardized certification for coding agents (Sector: Policy/Regulation)

- Action: Establish industry standards (e.g., minimum SecPass per domain) for certifying AI coding agents used in regulated sectors.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Independent testing labs; public scorecards; compliance frameworks akin to SOC2/ISO27001 for agent usage.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Multi-stakeholder consensus; legal frameworks; ongoing maintenance of certified benchmarks.

- Continuous security monitoring and drift detection for agents (Sector: MLOps/SRE)

- Action: Track long-term security performance of agents, detect degradation or drift, and trigger retraining or guardrail updates.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “Security Telemetry” pipelines; drift metrics for SecPass; automated rollback and quarantine of failing agent workflows.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Stable baselines; data privacy compliance; reliable change attribution mechanisms.

- Privacy/PII compliance enforcement for agent code (Sector: Healthcare/Finance)

- Action: Combine static and dynamic analyses to ensure agent outputs do not mishandle sensitive data and meet regulatory requirements.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: PII detectors; data flow taint analysis; compliance test suites mapped to HIPAA/GDPR.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate detection with low false positives; regulatory interpretations encoded in tests; organizational readiness.

- IDE-level real-time “Agent Security Score” and recommendations (Sector: Developer Tools)

- Action: Surface predictive risk scoring in the IDE as agents propose patches; offer secure alternatives and automatic refactor suggestions.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: On-device/static analyzers; lightweight test runners; security hinting systems; CWE-aware code actions.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Fast inference and testing; developer acceptance; effective UX that avoids alert fatigue.

- Robust environment-building automation (Sector: DevOps/Infrastructure)

- Action: Generalize the automated Docker/CI recreation approach to complex monorepos and polyglot stacks.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: “Environment Builder” services; CI synthesis agents; test output parsers for heterogeneous runners.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to internal build pipelines; accurate dependency resolution; cost and performance constraints.

- Security-aware model fine-tuning for CWE recognition and mitigation (Sector: AI/Model Development)

- Action: Improve agents’ ability to correctly identify relevant CWEs pre-implementation and to apply secure patterns reliably.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Fine-tuning datasets with feature requests, CWE tags, and secure patches; evaluation suites focused on CWE recall/precision.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High-quality labeled data; avoiding functionality regressions; generalization across domains.

- Sector-specific secure vibe coding playbooks (Sector: Robotics, Energy, Industrial IoT)

- Action: Publish tailored workflows for safety-critical systems, defining where vibe coding is permissible and the guardrails required.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Domain-specific checklists; formal verification hooks for critical modules; strict isolation of agent changes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Domain experts define boundaries; tooling for formal checks; conservative integration policies.

- Regulatory guidance on AI-assisted coding (Sector: Public Policy)

- Action: Develop public standards (e.g., NIST/ENISA guidance) on evaluating and deploying coding agents, including repository-level security testing requirements.

- Tools/Products/Workflows: Public benchmarks and conformance suites; reporting obligations on agent-related incidents.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Cross-sector collaboration; alignment with existing secure software development frameworks.

Notes on Assumptions and Feasibility

- Current benchmark coverage is Python-centric; generalization requires language-specific datasets and runners.

- Many applications depend on the existence and quality of repository-level test suites; where lacking, test augmentation is necessary.

- Pass@1 reflects typical single-shot usage of vibe coding; organizations may choose multi-shot or human-in-the-loop workflows to improve outcomes.

- Security prompting alone is insufficient and can harm functionality; treat guardrails as complementary to testing, not a replacement.

- Compute and orchestration costs for multi-agent/ensemble workflows must be justified by security gains; prioritize high-risk modules.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.