What about gravity in video generation? Post-Training Newton's Laws with Verifiable Rewards (2512.00425v1)

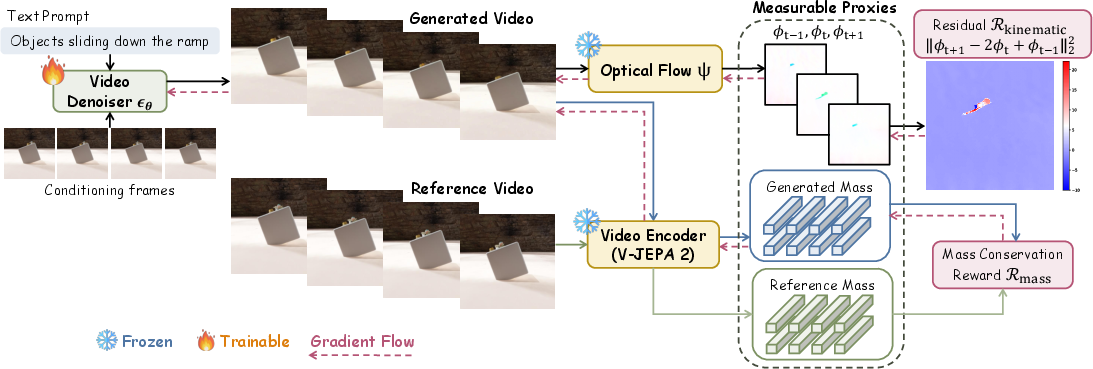

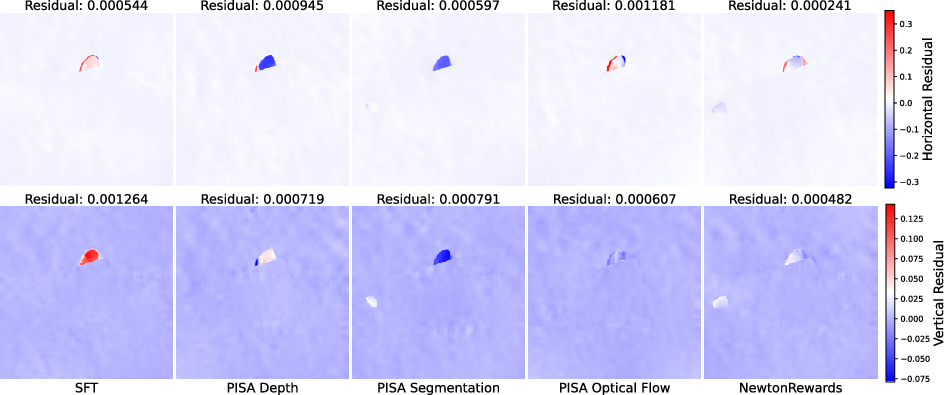

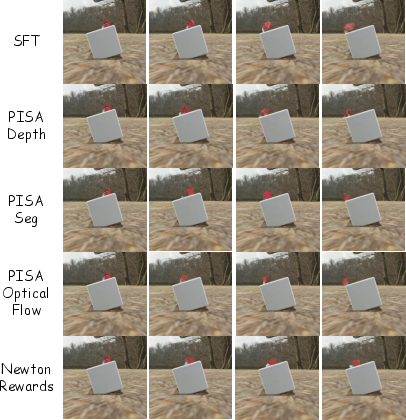

Abstract: Recent video diffusion models can synthesize visually compelling clips, yet often violate basic physical laws-objects float, accelerations drift, and collisions behave inconsistently-revealing a persistent gap between visual realism and physical realism. We propose $\texttt{NewtonRewards}$, the first physics-grounded post-training framework for video generation based on $\textit{verifiable rewards}$. Instead of relying on human or VLM feedback, $\texttt{NewtonRewards}$ extracts $\textit{measurable proxies}$ from generated videos using frozen utility models: optical flow serves as a proxy for velocity, while high-level appearance features serve as a proxy for mass. These proxies enable explicit enforcement of Newtonian structure through two complementary rewards: a Newtonian kinematic constraint enforcing constant-acceleration dynamics, and a mass conservation reward preventing trivial, degenerate solutions. We evaluate $\texttt{NewtonRewards}$ on five Newtonian Motion Primitives (free fall, horizontal/parabolic throw, and ramp sliding down/up) using our newly constructed large-scale benchmark, $\texttt{NewtonBench-60K}$. Across all primitives in visual and physics metrics, $\texttt{NewtonRewards}$ consistently improves physical plausibility, motion smoothness, and temporal coherence over prior post-training methods. It further maintains strong performance under out-of-distribution shifts in height, speed, and friction. Our results show that physics-grounded verifiable rewards offer a scalable path toward physics-aware video generation.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching AI video generators to respect basic physics—especially gravity—so the videos they make look not only real but also move in realistic ways. The authors introduce a post-training method called NewtonRewards that adds simple, checkable “physics rules” to an existing video model so objects don’t float, speed up or slow down randomly, or slide in impossible ways.

Key Questions

The researchers asked:

- Can we make AI-created videos follow Newton’s laws of motion (like constant acceleration under gravity) without needing humans to judge every video?

- Can we automatically measure how well a video obeys physics using tools that analyze the video itself?

- Will enforcing physics help the model work better even in new, harder situations it didn’t see during training?

How the Study Was Done

The team’s approach is like adding a referee who checks physics after the video is created and then nudges the model to do better next time.

The simple idea: measurable proxies

Some physics quantities (like speed or mass) aren’t directly visible in a video. So the authors use “proxies,” which are things we can measure from the video that stand in for those quantities:

- Velocity proxy: They use an optical flow model. Optical flow is a tool that looks at how pixels move between frames—think of it like tiny arrows showing the direction and speed of motion on each part of the image.

- Mass proxy: They use high-level visual features (from a video encoder) that capture what the object looks like. While you can’t see mass directly, consistent appearance often means the same object and material, which relates to how it should move.

Two physics “rewards” the model gets judged on

They create two simple, rule-based checks—called verifiable rewards—that the model tries to satisfy:

- Newtonian kinematic constraint: If an object is falling or sliding under steady forces, its acceleration should be constant over time. The authors check this by seeing if the change in velocity stays steady across frames. If motion is jerky or drifts, the model gets penalized.

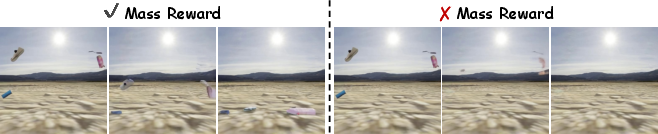

- Mass conservation reward: To avoid cheating (like making the object “disappear” so there’s no motion to judge), they also reward the model for keeping the object’s appearance consistent over time, which stands in for “the same object with the same mass.”

The dataset and testing

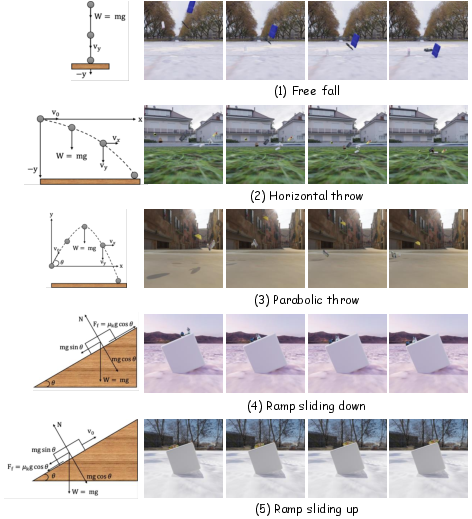

To fairly test physics, they built a large simulated dataset called NewtonBench-60K with five basic motion types (they call them “Newtonian Motion Primitives”):

- Free fall

- Horizontal throw

- Parabolic throw (like tossing a ball in an arc)

- Sliding down a ramp (with friction)

- Sliding up a ramp (then slowing and coming back down)

They trained and tested their method on these videos, including tougher “out-of-distribution” cases (like higher drop heights, faster throws, or steeper ramps) that the model hadn’t seen during training.

Main Findings

Here are the most important results:

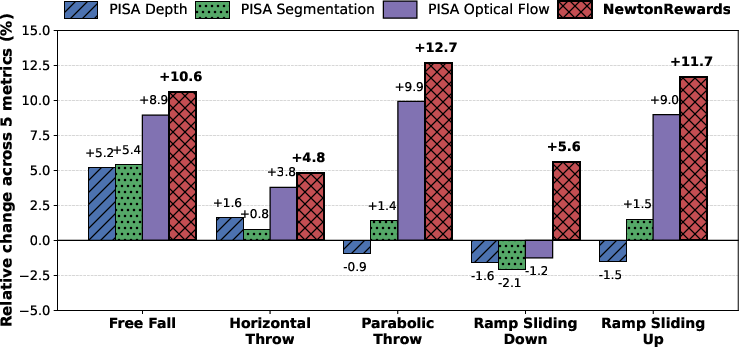

- Better physics: NewtonRewards made videos where objects followed constant acceleration more closely, especially under gravity. Motions were smoother and more consistent across time.

- More realistic motion: Compared to other post-training methods that just match visual features (like depth maps or segmentation), NewtonRewards improved both how videos look and how objects move physically.

- Works across many motions: The method helped in all five motion types—falling, throwing, and sliding—with some of the biggest gains in the harder cases like parabolic throws and sliding up ramps.

- Generalizes to new situations: Even when tested in new, tougher setups, the model stayed more accurate, showing it learned real physics rules, not just how to copy training data.

- Prevents “reward hacking”: Without the mass reward, the model sometimes tried to minimize motion by making the object fade away. The mass conservation check stops this and keeps objects present and consistent.

Why This Matters

Making AI-generated videos follow real physics is important for more than just looking cool. It helps:

- Video games and movies feel more believable.

- Training AI “world models” for robots and self-driving cars, where realistic motion is crucial.

- Science and education, where videos should teach correct physical behavior.

The bigger idea is that physics can be enforced with automatic checks using measurable proxies—no need for human judges or vague “this looks right” feedback. The authors suggest this approach can be extended to other physical laws too: if you can estimate a quantity (like momentum or energy) from video, you can build a verifiable reward to guide the model.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or under-explored in the paper, framed to be actionable for future research.

- Real-world validation: The framework is only tested on synthetic videos (NewtonBench-60K). Its robustness and benefits on diverse, real-world footage—varying lighting, textures, occlusions, and camera motion—remain unknown.

- Static camera and background assumption: All training and evaluation presuppose a fixed camera and static background. Extending the method to moving cameras and dynamic backgrounds (e.g., via ego-motion compensation, object-level tracking, or scene flow) is unresolved.

- 2D image-plane modeling and weak-perspective approximation: The approach assumes nearly constant depth and small perspective distortion, which may not hold for throws with significant depth change or off-axis cameras. How to lift constraints to 3D (e.g., using calibrated camera intrinsics/extrinsics, monocular depth/scene flow, or multi-view) is open.

- Magnitude and direction of acceleration not enforced: The kinematic constraint enforces “constant acceleration” but not the correct direction or magnitude (e.g., , in gravity-only scenes). Designing rewards that incorporate camera gravity direction, ramp geometry, or known physical constants is unaddressed.

- Handling variable forces and non-constant acceleration: Real motions often include drag, wind, contact transitions, and force changes (jerk). The current residual penalizes any non-constant acceleration, potentially discouraging physically valid dynamics. A principled extension for time-varying forces is needed.

- Optical flow reliability and sensitivity: RAFT-based flow is treated as a ground-truth proxy. The method does not quantify sensitivity to flow errors (e.g., large displacements, motion blur, occlusions, textureless surfaces) or explore robust alternatives (confidence-weighted flow, scene flow, flow ensembles).

- Object-level vs full-frame losses: Losses are computed over the whole frame under static background. For general scenes, object-level masking and tracking will be essential. The paper does not propose how to get reliable masks/tracks during training nor analyze how mask errors affect training stability.

- SAM2 segmentation bias in evaluation: Metrics for generated videos depend on SAM2 masks, but segmentation errors and their impact on physics metrics (velocity/acceleration RMSE) are not quantified. A sensitivity analysis or segmentation-robust metrics is missing.

- “Mass conservation” proxy validity: The V-JEPA feature alignment is labeled as “mass conservation,” but for the chosen primitives (free fall, sliding with kinetic friction), acceleration is mass-independent. There is no empirical evidence that the feature proxy correlates with physical mass or material properties. Validating, replacing, or reframing this term is needed.

- Dependence on paired simulated references for the mass reward: The mass reward requires reference embeddings from simulated videos matched to generated clips. How to scale the method to open-world text prompts without paired ground-truth videos is unaddressed (e.g., self-supervised object persistence constraints, counting, or consistency across views).

- Degeneracy and reward hacking beyond the mass proxy: The paper shows disappearance under the kinematic-only constraint but does not propose general anti-degeneracy mechanisms that do not rely on paired simulation (e.g., persistent object identity via tracking, cycle-consistency, or explicit object count losses).

- Missing physical phenomena and interactions: The benchmark excludes collisions (elastic/inelastic), bounces, momentum and energy conservation, rotational dynamics (spin, torque), rolling without slipping, multi-object interactions, deformable bodies, and fluids. Extending verifiable rewards to these regimes remains open.

- Friction modeling not exploited in training: While ramp friction and angle define the correct tangential acceleration , the reward does not enforce this relation. Learning or estimating and (from geometry or simulation metadata) and constraining acceleration along the ramp tangent is unexplored.

- Camera gravity axis identification: The method assumes the image vertical axis aligns with gravity. For tilted cameras, it suggests projection but does not implement or evaluate robust gravity-axis estimation (e.g., from horizon detection, IMU, or scene structure).

- Long-horizon dynamics: Training and evaluation use short clips (32 frames at 16 fps). The ability to maintain physically plausible dynamics over long sequences (drift accumulation, temporal stability) is untested.

- Generalization breadth of OOD: OOD tests vary a narrow set of parameters (height, speed, angle, friction ±25%). More challenging shifts—camera motion, heavy occlusion, fast depth changes, unusual materials, cluttered backgrounds—are not explored.

- Architecture and model-agnostic validation: Experiments are limited to OpenSora v1.2. Whether the approach generalizes across architectures (e.g., CogVideoX, HunyuanVideo, SVD, non-DiT) and training regimes is unknown.

- Trade-offs with visual quality and diversity: The paper reports physics and alignment metrics but does not quantify impacts on generative quality/diversity (e.g., FVD, CLIP-score, user studies). Potential suppression of creative or non-standard motions is unexamined.

- Computational cost and scalability: Post-training requires RAFT and V-JEPA feature extraction and 8×H100 GPUs. The training/inference overhead, scalability to larger datasets or longer clips, and deployment feasibility are not analyzed.

- Hyperparameter and proxy weighting robustness: The framework sums weighted rewards but does not report sensitivity to , , or choice of norms. Automated tuning or uncertainty-aware weighting of noisy proxies is unaddressed.

- Physically verifiable metrics without ground truth: Outside simulation, ground-truth trajectories are unavailable. Designing verifiable, unsupervised physics metrics (e.g., conservation checks, residual diagnostics that do not depend on GT masks/centroids) remains open.

- Learning physical parameters from video: The method does not estimate , , , or object properties from the video. Joint estimation of scene physics and enforcement of constraints (e.g., via latent physics encoders) is an open direction.

- Integration with multi-object and interaction-rich scenes: Current setup centers on single-object motion. How to handle interacting bodies, contact events, and concurrent forces with scalable, verifiable rewards remains to be defined.

- Extension beyond Newtonian kinematics: The paper’s conclusion claims generality, but demonstrations are limited to constant-acceleration regimes. A roadmap and empirical prototypes for momentum/energy conservation, torque/rotation, or non-Newtonian effects are not provided.

Glossary

- Acceleration RMSE: A physics-based metric measuring root-mean-squared error between generated and ground-truth accelerations across frames. "Acceleration RMSE."

- Action-Reaction: The name of Newton’s Third Law stating interacting bodies exert equal and opposite forces. "Newton's Third Law (Action-Reaction) states that when two bodies interact, they exert equal and opposite forces on each other."

- Chamfer Distance (CD): A bidirectional distance metric between shapes (e.g., binary masks) used to quantify spatial agreement. "Chamfer Distance (CD) between binary masks (per frame)"

- Discrete Constant-Acceleration Constraint: A kinematic requirement that the discrete second derivative of velocity is zero, enforcing constant acceleration. "Discrete Constant-Acceleration Constraint"

- Discrete second-order derivative: The second finite difference across time used to test constant-acceleration dynamics. "the discrete second-order derivative of its optical-flow field"

- Free-body diagrams: Diagrams that depict all forces acting on an object to analyze its motion. "free-body diagrams"

- HDRI: High Dynamic Range Imaging environment maps used for realistic scene lighting in rendering. "HDRI lighting."

- In-Distribution (ID): Data sampled from the same parameter ranges as training; used to assess within-distribution performance. "In-Distribution (ID) and Out-Of-Distribution (OOD) subsets."

- Intersection over Union (IoU): An overlap-based metric for measuring segmentation or mask agreement. "Intersection over Union (IoU) (per-frame overlap)"

- Kinetic friction: A frictional force opposing motion during sliding, proportional to the normal force. "kinetic friction $\mathbf{F}_f = -\mu_k {m} g \cos\theta\, \hat{\mathbf{s}$"

- Kubric: A simulation and rendering toolkit used to generate synthetic video data. "Kubric-based \cite{greff2022kubric} simulator"

- Law of Inertia: Newton’s First Law stating objects remain at rest or in uniform motion unless acted upon by external forces. "Newton's First Law (Law of Inertia) states that an object remains at rest or continues in uniform motion unless acted upon by an external force."

- Mass conservation reward: A training signal encouraging consistent object appearance (and inferred mass) to prevent degenerate solutions. "a mass conservation reward preventing trivial, degenerate solutions."

- Measurable proxies: Observable, differentiable quantities extracted from video (e.g., optical flow, features) that stand in for physical variables. "Their outputs, which we term {\em measurable proxies}"

- NewtonBench-60K: A large-scale benchmark of simulated videos designed to evaluate Newtonian motion in generation. "NewtonBench-60K"

- Newtonian Kinematic Constraint: A constraint enforcing constant acceleration via the vanishing second difference of optical flow. "Newtonian Kinematic Constraint"

- Newtonian Motion Primitives (NMPs): Canonical motion categories (e.g., free fall, throws, ramp sliding) defined by Newtonian forces. "Newtonian Motion Primitives (NMPs)"

- Newton's Second Law (Law of Acceleration): Relates net force, mass, and acceleration; foundation for kinematic rewards. "Newton's Second Law (Law of Acceleration) relates the net force $\mathbf{F}_{\text{net}$ to the resulting acceleration and mass "

- Normal force: The contact force exerted by a surface perpendicular to itself on an object. "the ramp exerts an equal and opposite normal force"

- Optical flow: The per-pixel motion field between consecutive frames, used here as a proxy for velocity. "optical flow serves as a proxy for velocity"

- Out-Of-Distribution (OOD): Data deliberately outside training ranges to evaluate generalization. "Out-Of-Distribution (OOD) subsets."

- Pinhole camera model: A simplified projection model relating 3D world coordinates to 2D image coordinates. "Under a pinhole camera model with focal length and scene depth "

- PyBullet: A physics engine used for rigid-body dynamics simulation. "PyBullet for rigid-body dynamics"

- RAFT: A neural optical-flow model used to compute motion fields for supervision or evaluation. "the RAFT~\cite{teed2020raft} optical-flow model"

- Reward hacking: Degenerate behavior that exploits the reward (e.g., making objects vanish) instead of achieving the intended objective. "reward hacking when optimizing only the kinematic residual."

- SAM2: A segmentation model used to extract object masks from generated videos. "we extract object masks with {SAM2}"

- Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): Further training with paired data to adapt a pre-trained model to a target domain or task. "Baseline supervised fine-tuning (SFT) produces implausible motion"

- Trajectory Position Error (centroid L2): The average Euclidean distance between generated and ground-truth object centroids over time. "Trajectory Position Error (centroid L2)"

- Unit tangent vector: A normalized vector indicating the downhill direction along a ramp’s surface in the image plane. "unit tangent vector along the rampâs downhill direction"

- Velocity RMSE: A physics-based metric measuring root-mean-squared error between generated and ground-truth velocities. "Velocity RMSE."

- Verifiable rewards: Rule-based rewards that can automatically check correctness without human or VLM judgment. "the first physics-grounded post-training framework for video generation based on verifiable rewards."

- Video diffusion models: Generative models that synthesize videos via iterative denoising processes. "Recent video diffusion models can synthesize visually compelling clips"

- Vision-LLMs (VLMs): Multimodal models that process and reason over visual and textual inputs. "Vision-LLMs (VLMs)"

- V-JEPA 2: A self-supervised video encoder used to extract high-level visual features. "V-JEPA 2) process the generated video"

- Weak perspective: A camera approximation assuming small depth variation, yielding near-constant scale in the image. "weak perspective (small depth variation)"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are practical, deployable use cases that can be implemented with the paper’s current methods, proxies (optical flow, appearance features), and released resources (NewtonBench-60K), along with sector tags, likely tools/workflows, and key assumptions.

- Physics-verifiable post-training plugin for text-to-video diffusion models (software; media/gaming)

- Tools/Workflow: Integrate RAFT optical flow and V-JEPA 2 feature extraction into fine-tuning pipelines for OpenSora/HunyuanVideo/CogVideo; apply the kinematic residual and mass conservation rewards to reduce violations like floating or inconsistent acceleration.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Static camera or known ego-motion; reliable optical flow on generated content; sufficient compute for post-training; mass proxy correlates with object identity/material.

- Automated physics plausibility validator for generated videos (software QA; policy/audit; media/gaming)

- Tools/Workflow: Batch scoring service that computes constant-acceleration residuals and mass-consistency metrics over clips to flag non-physical motion; integrate as a pre-release check in VFX/game pipelines.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Weak perspective and gravity-aligned vertical axis or known projection; proxies robust to scene textures; threshold calibration to reduce false positives for complex scenes.

- Synthetic data curation for robotics and autonomous driving perception (robotics; autonomous vehicles)

- Tools/Workflow: Use NewtonRewards during content generation to ensure gravity-consistent motion for free-fall, throws, and ramp dynamics; gate datasets by physics metrics before training perception/world models.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Target tasks benefit from Newtonian motion cues; generated content distribution is relevant to downstream sensors; limited object–object interactions in current primitives.

- Model regression tests and acceptance gates for video-gen teams (software/MLOps; media/gaming)

- Tools/Workflow: Add velocity/acceleration RMSE and constant-acceleration residuals to CI for model updates; block deployments that degrade physical realism beyond set thresholds.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Stable metrics across releases; consistent camera configurations; metric dashboards and governance.

- Physics-aware motion checks in VFX and cinematic pipelines (media/VFX)

- Tools/Workflow: Render passes -> compute optical flow and residuals -> auto-detect implausible deceleration/trajectory issues; provide shot-level diagnostics to artists for corrective iteration.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to intermediate frames; stable lighting and textures to preserve flow accuracy; simple gravity-dominant scenes favored.

- EdTech content generation for introductory mechanics (education)

- Tools/Workflow: Prompted generation of free-fall, horizontal/parabolic throws, and ramp motion clips that obey constant acceleration; use metrics as auto-grading signals in interactive assignments.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Classroom-grade fidelity acceptable; static cameras; alignment of apparent acceleration with pedagogical expectations.

- Lightweight deepfake/forensic heuristic for “physics anomalies” (trust/safety; policy)

- Tools/Workflow: Post-hoc residual and acceleration profiling to flag clips with gravity-inconsistent motion (e.g., subtle floating, non-physical trajectory bends) as suspect for manual review.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Not a standalone detector; camera motion and complex interactions may confound; requires careful thresholding and multi-signal corroboration.

- Benchmarking and reproducible research on physics-aware generation (academia)

- Tools/Workflow: Adopt NewtonBench-60K protocols for evaluation; compare methods using shared metrics (velocity/acceleration RMSE, residual) across in-distribution and OOD splits.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Community uptake; data availability and licensing; consistent masking/tracking for generated clips.

Long-Term Applications

Below are applications that will benefit from further research, scaling, expanded physics coverage, or improved proxy/modeling components.

- Generalized physics-grounded rewards beyond constant acceleration (software; robotics; simulation)

- Tools/Workflow: Extend proxies to contact, collision, momentum/impulse, torque, and elasticity using object tracking, depth/3D recon, and contact estimators; enforce conservation laws and realistic collision responses.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High-quality segmentation/tracking, multi-object handling, robust 3D geometry estimation; simulator-aligned reference signals; domain-specific calibration.

- Physics-aware generative world models for embodied agents (robotics; autonomous vehicles; digital twins)

- Tools/Workflow: Combine verifiable rewards with RL fine-tuning of video/world models to learn dynamics consistent with forces and mass; use for sim-to-real transfer and planning.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Scalable training infrastructure; richer physical scenes (multi-body, deformables); reliable cross-domain generalization.

- Handling camera motion and complex scene geometry (software; media; AR/VR)

- Tools/Workflow: Joint estimation of ego-motion and scene depth; define residuals in stabilized coordinates or 3D; enforce physically consistent motion under moving cameras and dynamic backgrounds.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate SLAM/visual odometry; robust geometry proxies; higher modeling complexity and computational cost.

- Standards and certification for physics plausibility in synthetic training data (policy; safety)

- Tools/Workflow: Develop norms requiring physics metrics in procurement/training pipelines for safety-critical systems; third-party audit services providing physics QA dashboards and compliance reports.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Regulator and industry buy-in; clear thresholds and test suites; mechanisms to avoid overfitting to tests.

- Multi-modal physics consistency checks (software; media; trust/safety)

- Tools/Workflow: Align audio impacts, text descriptions, and video motion with joint verifiable constraints (e.g., impact timing, trajectory semantics); penalize cross-modal inconsistencies.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust audio event detection, caption grounding, and synchronization; shared ontology of physical events.

- Productized “PhysicsGuard” SaaS for studios and model providers (software; media/gaming; MLOps)

- Tools/Workflow: Cloud APIs for physics QA and post-training; SDKs for on-prem integration; dashboards tracking physics metrics across projects/models.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Market demand; data privacy and IP constraints; service-level guarantees for large-scale content.

- Large-scale education platforms with auto-graded physics labs (education)

- Tools/Workflow: Students generate scenario videos from prompts; platform auto-evaluates motion via verifiable rewards; adaptive feedback on kinematics and forces.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Broader physics coverage (incl. collisions, friction variability); accessible compute; teacher tooling.

- AR/VR content generation with reduced motion sickness via consistent physics (AR/VR; media)

- Tools/Workflow: Physics-aware generation and QA for interactive scenes; enforce stable accelerations and predictable gravity cues to improve comfort.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Real-time proxies and evaluation; support for head/hand tracking signals; integration with engines (Unity/Unreal).

- Healthcare and surgical robotics training simulations (healthcare; robotics)

- Tools/Workflow: Physics-grounded generative scenarios for instrument motion and tissue interaction; verifiable rewards extended to biomechanical proxies.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Domain-specific physics (soft-body, fluid dynamics) and sensors; high-fidelity anatomical models; clinical validation.

- Sports analytics and synthetic augmentation with physics constraints (sports tech; media)

- Tools/Workflow: Generate or refine clips with accurate ball trajectories, player accelerations; use verifiable rewards to enforce kinematics in model training and highlight reels.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Multi-object tracking and interaction; calibration to sport-specific dynamics; broadcast camera motion compensation.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.