TraceGen: World Modeling in 3D Trace Space Enables Learning from Cross-Embodiment Videos (2511.21690v1)

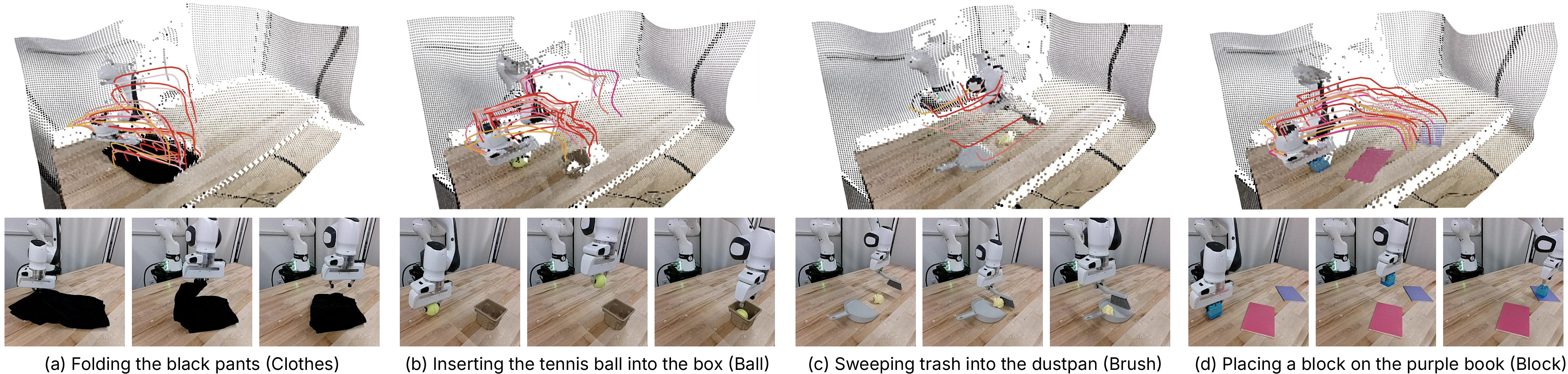

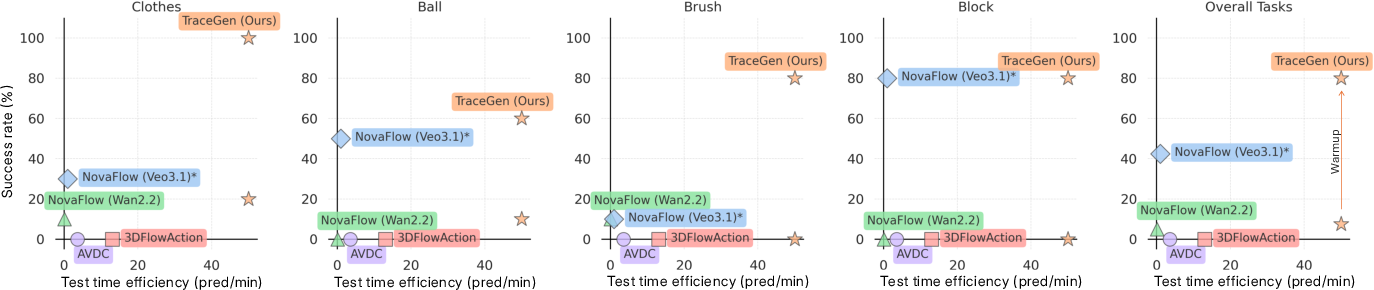

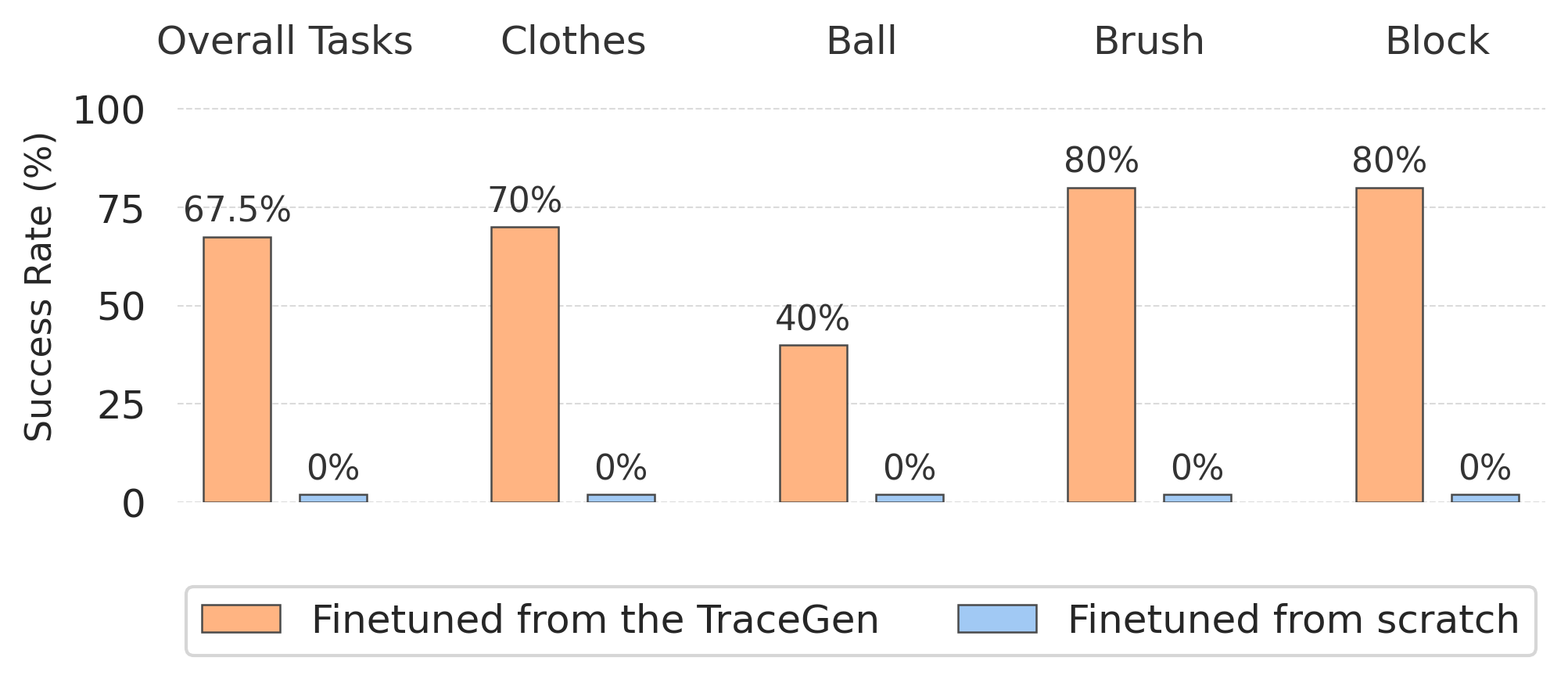

Abstract: Learning new robot tasks on new platforms and in new scenes from only a handful of demonstrations remains challenging. While videos of other embodiments - humans and different robots - are abundant, differences in embodiment, camera, and environment hinder their direct use. We address the small-data problem by introducing a unifying, symbolic representation - a compact 3D "trace-space" of scene-level trajectories - that enables learning from cross-embodiment, cross-environment, and cross-task videos. We present TraceGen, a world model that predicts future motion in trace-space rather than pixel space, abstracting away appearance while retaining the geometric structure needed for manipulation. To train TraceGen at scale, we develop TraceForge, a data pipeline that transforms heterogeneous human and robot videos into consistent 3D traces, yielding a corpus of 123K videos and 1.8M observation-trace-language triplets. Pretraining on this corpus produces a transferable 3D motion prior that adapts efficiently: with just five target robot videos, TraceGen attains 80% success across four tasks while offering 50-600x faster inference than state-of-the-art video-based world models. In the more challenging case where only five uncalibrated human demonstration videos captured on a handheld phone are available, it still reaches 67.5% success on a real robot, highlighting TraceGen's ability to adapt across embodiments without relying on object detectors or heavy pixel-space generation.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces TraceGen, a new way to teach robots to do tasks by learning from videos of different “embodiments” (like humans and various robots) and different environments. Instead of learning from raw pictures (pixels), TraceGen learns from a simplified 3D “trace” of motion—like the path objects and hands move through space. This helps the robot understand what should move where, without getting confused by camera angles, colors, or backgrounds.

What questions did the paper try to answer?

- Can robots quickly learn new tasks with only a few examples?

- Can robots learn from videos of humans and other robots even when cameras, bodies (hands vs. robot arms), and scenes are different?

- Is there a better, faster way to model the future (a “world model”) than generating full video frames?

How did they do it?

The big idea: “Trace-space” instead of pixels

- Imagine drawing the path of a hand and an object in 3D as they move—like a GPS trail, but for motion in a scene. The authors call this “trace-space.”

- Trace-space captures where and how things move in 3D, but ignores appearance (colors, textures) and background clutter. That makes learning simpler and faster.

Building the training data: TraceForge

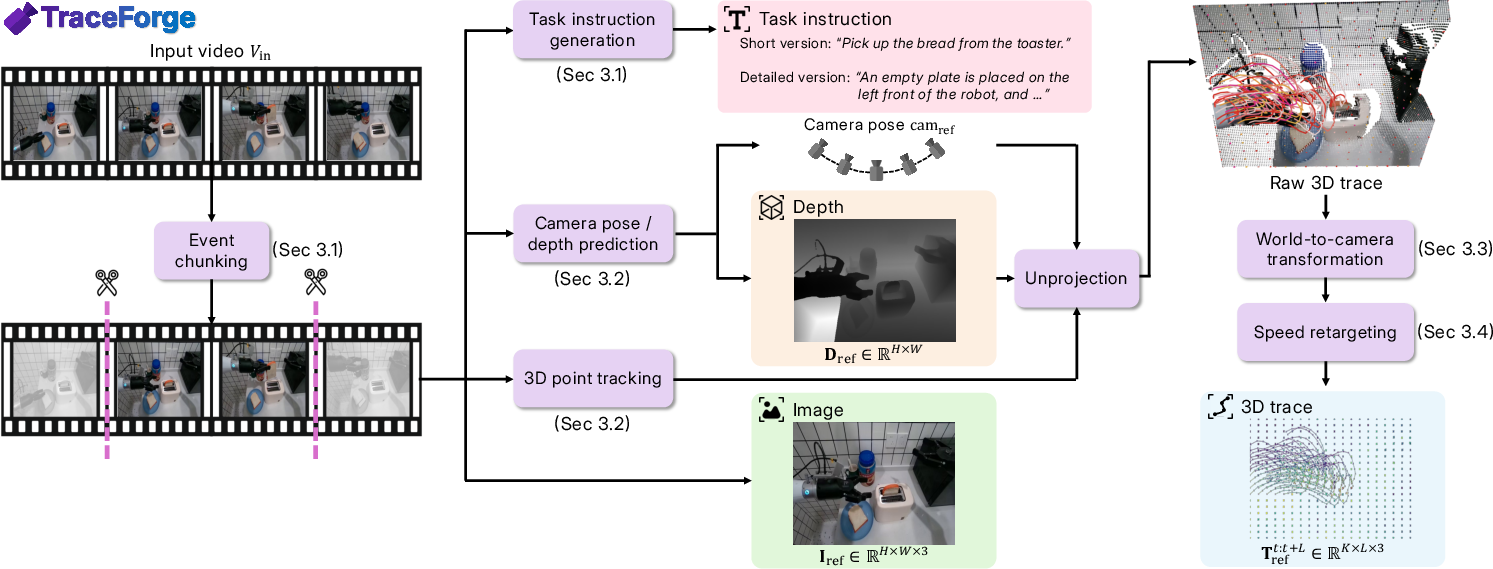

To train TraceGen, they created a large dataset from lots of human and robot videos. They used a pipeline called TraceForge to turn each video into clean 3D motion traces:

- Remove camera effects: If the camera is moving (like a handheld phone), they estimate the camera’s position so they can “undo” its motion.

- Track points over time: They place a regular grid of points on an image (like 20×20 dots) and track where those points move frame-by-frame in 3D (x, y, and depth z).

- Align everything to one view: They convert all traces to a single “reference camera” so the motion is consistent.

- Normalize speed: Human and robot demonstrations might be faster or slower. They re-sample the motion so traces have a consistent length and pacing while keeping the shape of the motion.

- Add language: Each clip gets task instructions in natural language (short commands, step-by-step, or casual phrasing), so the model learns to connect words to motion.

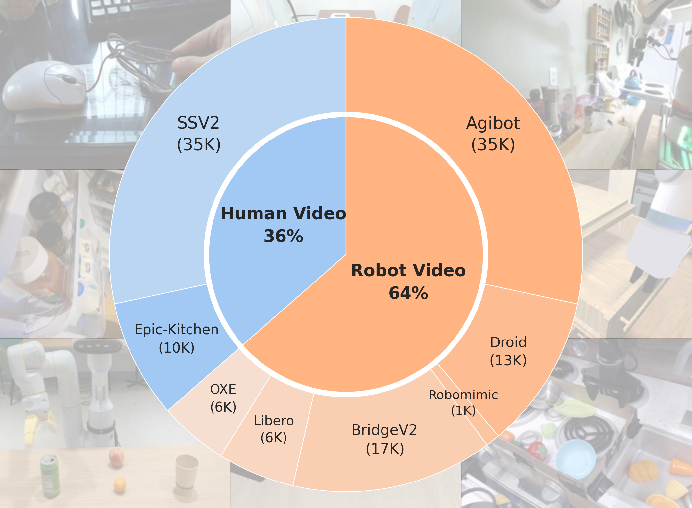

This produced a huge dataset: 123,000 videos and 1.8 million triplets of observation–trace–language, covering many kinds of scenes and cameras.

The model: TraceGen

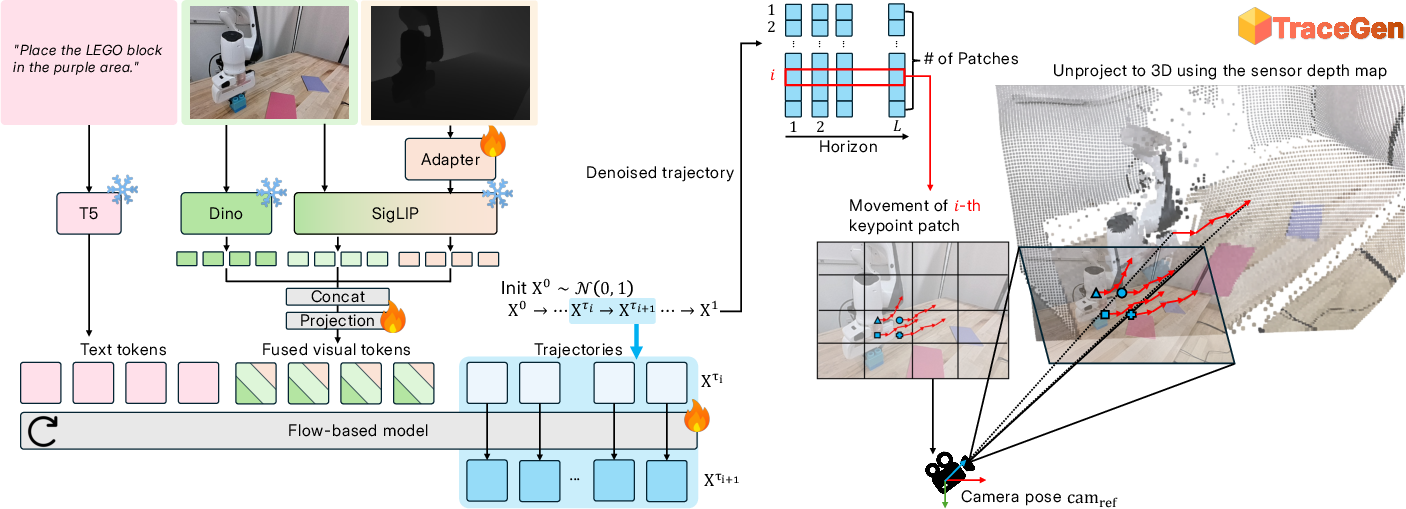

- Inputs: one RGB-D observation (color image + depth), plus a text instruction.

- Feature fusion: It uses strong pre-trained vision and language encoders to turn images and text into tokens (compact features), then combines them.

- Predicting motion: Instead of making future video frames, TraceGen predicts the next 3D motion increments for all the tracked points—like small steps that build a full path over time.

- How it generates: It uses a flow-based method (you can imagine starting from noisy guesses and smoothly nudging them toward the correct motion), which is much lighter and faster than making videos.

Executing on a robot

- The predicted 3D motion trace is turned into robot arm commands using inverse kinematics (a standard way to map desired end-effector positions to joint angles).

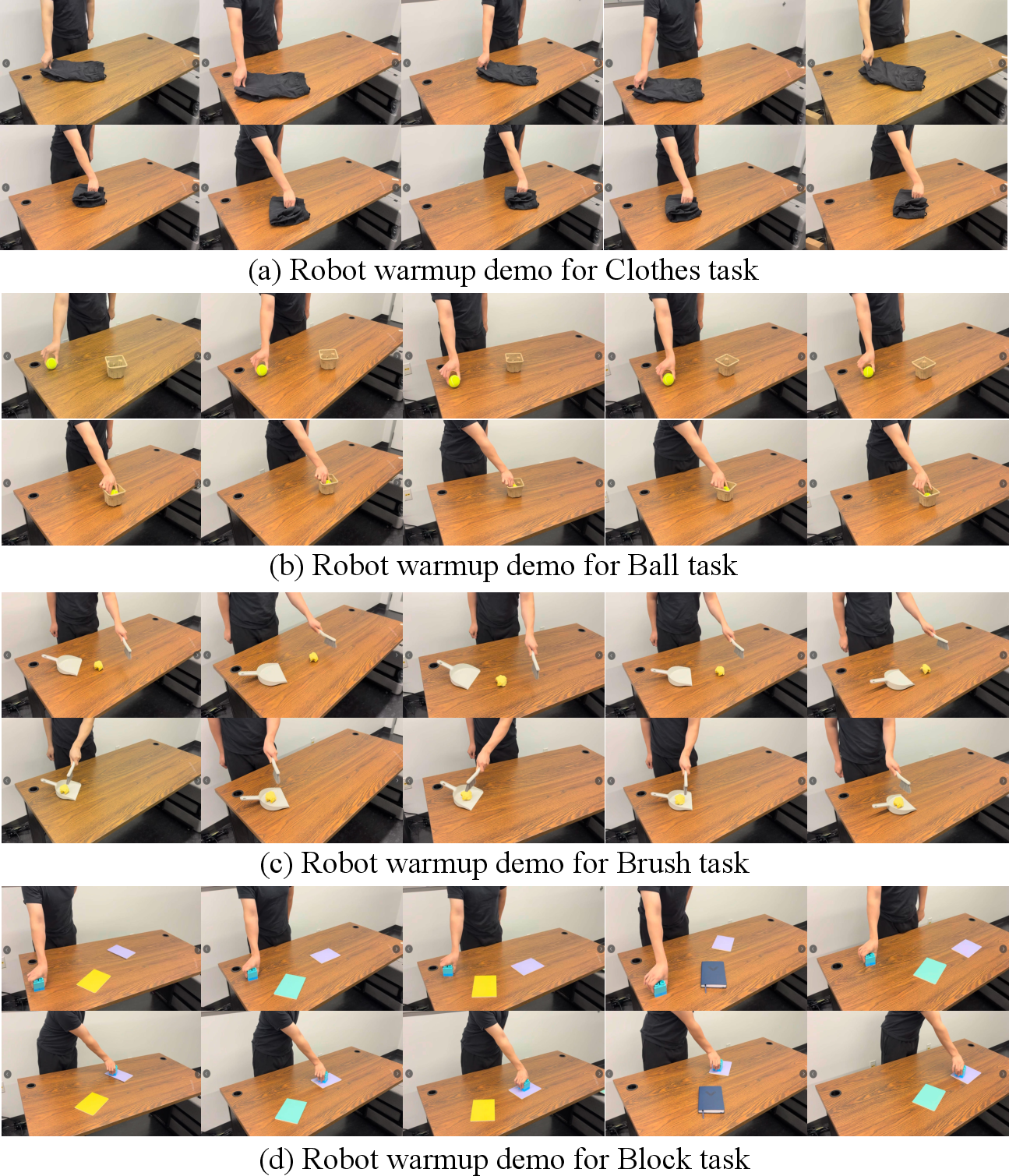

- A small “warm-up” (fine-tuning) helps align the predicted traces to a specific robot and task.

What did they find, and why is it important?

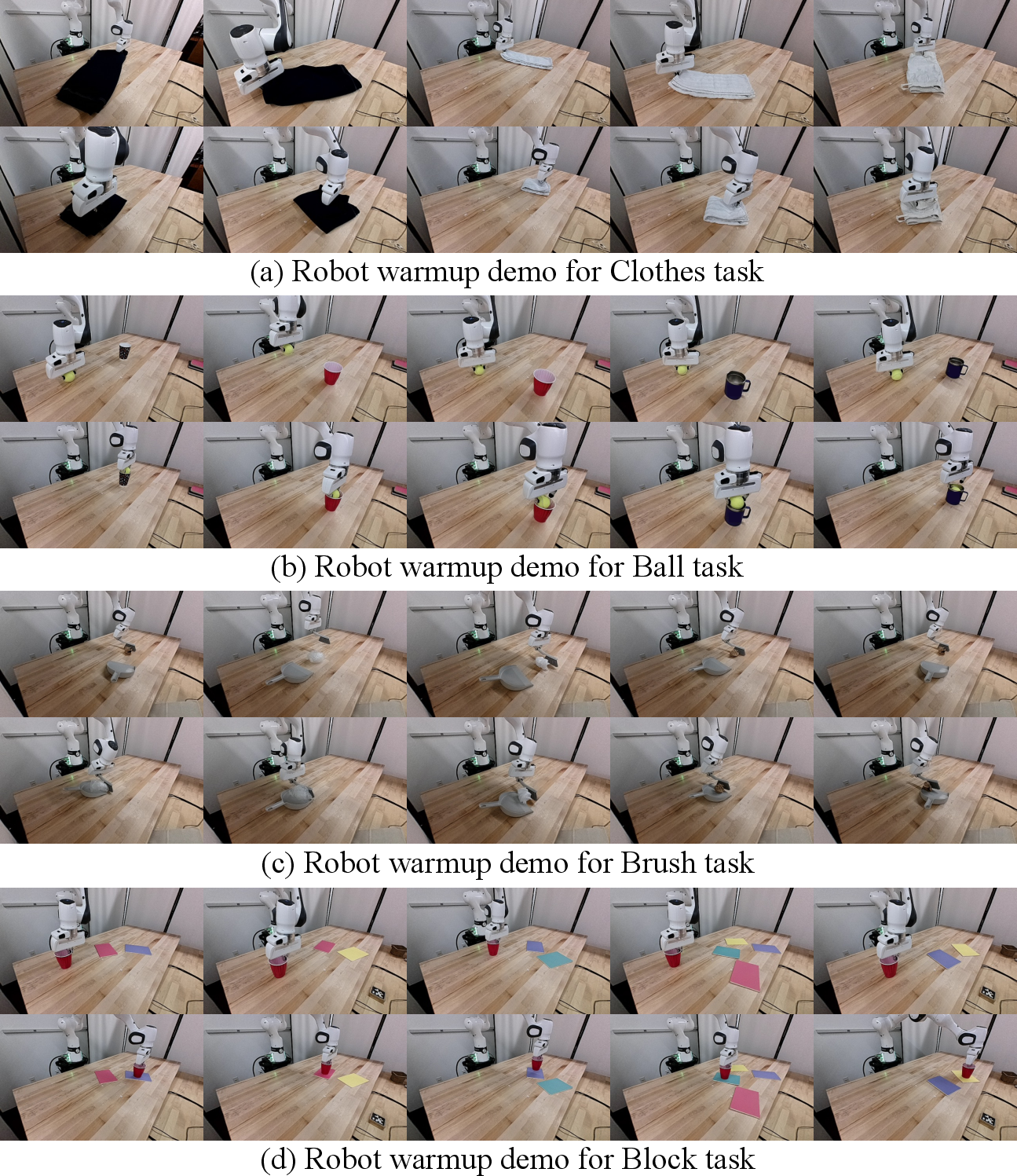

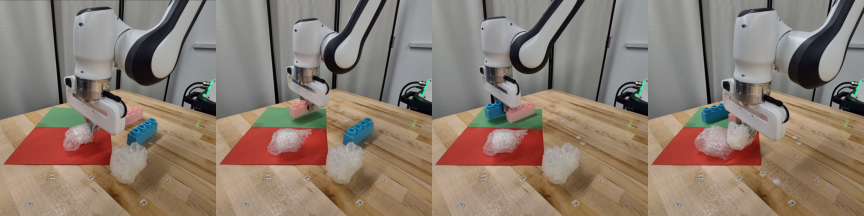

- Few-shot robot learning: With only five short robot demonstration videos, TraceGen reached 80% success across four real-world tasks (like sweeping with a brush or placing a block).

- Human-to-robot transfer: With only five handheld human videos (uncalibrated, different backgrounds), TraceGen still achieved 67.5% success on a real robot.

- Speed: TraceGen is 50–600× faster at inference than cutting-edge video-based world models, making it suitable for real-time planning.

- Scale and generality: Pretraining on their large cross-embodiment dataset gave TraceGen a strong “motion prior,” helping it adapt quickly to new robots and scenes without relying on object detectors or heavy video generation.

Why it matters:

- Robots can learn from everyday human videos, not just perfectly recorded robot data.

- Focusing on motion (trace-space) makes learning faster, cheaper, and more robust to visual distractions.

- This approach reduces the need for large amounts of expensive robot-specific demonstrations.

Implications and potential impact

- Practical training: Companies and labs could teach robots new skills in minutes using a few simple videos—potentially even phone recordings.

- Cross-embodiment learning: Robots can learn from humans and other robots, despite different bodies and cameras.

- Real-time planning: Because it avoids expensive video generation, robots can plan and adapt quickly during tasks.

- Foundations for generalist robots: A shared 3D motion representation could help build robots that generalize across many tasks, environments, and tools.

In short, TraceGen shows that modeling the world through compact 3D motion traces is a powerful, efficient way for robots to learn from diverse videos and perform useful tasks with very little data.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of the paper’s unresolved issues—what is missing, uncertain, or left unexplored—framed to guide concrete next steps for future research:

- Ambiguity control in generative trajectories: The model uses a linear stochastic-interpolant ODE without mechanisms to select among multiple plausible motion modes; how to conditionally steer generation (e.g., via latent codes, constraint-based decoding, or alternative schedules) remains open.

- Interpolant design and training objectives: Only linear schedules are explored; the impact of other stochastic interpolants, flow-matching variants, training losses, and solver choices on trajectory diversity, stability, and accuracy is untested.

- Closed-loop vs. open-loop planning: The system predicts a full 3D trace from a single RGB-D frame and instruction, then executes via IK; robustness of closed-loop replanning with online feedback (e.g., receding-horizon re-planning under disturbances) is not evaluated.

- Physical feasibility and constraint awareness: Generated traces may be kinematically or dynamically infeasible and occasionally “cut through” obstacles; there is no constraint-aware decoding or safety layer, joint-limit awareness, or collision checking integrated with generation.

- Contact- and force-aware control: The trace representation encodes positions of scene points but not forces, torques, or contact events; how to extend trace-space to capture contact timing, force profiles, or impedance constraints (especially for contact-rich tasks) is unexplored.

- Mapping scene-level traces to executable end-effector/action trajectories: The paper omits a precise algorithm for extracting actionable robot paths (e.g., end-effector pose and gripper state) from dense scene-point traces; the current “basic tracking controller + IK” approach lacks detail and ablation.

- Orientation and gripper state: Predicted traces are 3D point positions without orientation or gripper commands; how to represent and generate full 6-DoF trajectories with discrete gripper events remains open.

- Long-horizon and multi-step tasks: Experiments use short clips and L=32-step traces; scalability to long-horizon, multi-stage tasks with branching and temporal dependencies (beyond short decompositions in text) is not studied.

- Multi-object, clutter, and occlusion robustness: Uniform grid tracking may dilute salient object/effector motion and be sensitive to occlusions or tool-scale motions; systematic evaluation under heavy occlusion, clutter, and small tools is missing.

- Deformable and articulated objects at scale: While a “Clothes” task is shown, generalization to diverse deformables (cloth, cables) and articulated objects (drawers, doors, tools with joints) is not evaluated or modeled explicitly.

- Metric scale consistency across scenes: Screen-aligned (x, y) + depth z in a reference camera may introduce residual scale inconsistencies across videos with varying intrinsics; the paper lacks analysis on cross-scene metric alignment and its effect on transfer.

- Temporal normalization side effects: Speed retargeting normalizes duration by arc length; potential loss of time-critical cues (e.g., contact timing, dynamic feasibility) and its downstream impact on execution quality are unquantified.

- Dependence on 3D estimation quality: TraceForge relies on camera pose and depth from monocular predictors (VGGT, etc.) without 3D optimization; sensitivity to inaccuracies (e.g., scale drift, rolling shutter, motion blur, non-Lambertian surfaces) and error propagation into training is not characterized.

- Quantitative validation of trace accuracy: Beyond an appendix “sanity check,” there is no thorough, dataset-wide evaluation of trace reconstruction error (e.g., against motion-capture or multi-view ground truth), nor its correlation with downstream success.

- 2D-only trace co-training: ~20% of traces are 2D-only; the effect of mixing 2D and 3D supervision on metric consistency, depth reasoning, and performance is not ablated.

- Language grounding and instruction robustness: The model is text-conditioned but there is no systematic paper of instruction fidelity, robustness to paraphrases/ambiguity, or failure modes when language conflicts with visual context.

- VLM-generated instruction quality: Many task instructions are synthesized by a VLM; the degree of hallucination, misalignment with traces, and their impact on training (and how to filter/verify them) is not analyzed.

- Generalization breadth across embodiments: Experiments use one target robot (Franka) and 4 tasks; transfer to substantially different embodiments (mobile manipulators, multi-finger hands, humanoids, legged platforms) is not tested.

- Environment and object diversity: Real-world evaluation is limited to a single lab setup; generalization to different sensors, lighting, backgrounds, object categories/materials, and domain shifts is not systematically measured.

- Safety and recovery behaviors: No discussion of failsafe behaviors, recovery from execution errors, or safety constraints (workspace limits, human-in-the-loop veto) during trace execution.

- Real-time performance under control-loop constraints: While throughput is reported, the system’s latency and determinism under strict control cycles (e.g., 100–500 Hz) on robot hardware are not characterized.

- Representation choices and ablations: Key design choices (grid resolution, patch size, increments vs. absolute coordinates, conditioning modalities, fusion strategy, encoder freezing) lack ablation to quantify their contributions.

- Comparison breadth: Baselines exclude constraint-aware planners and recent state-of-the-art 3D scene-flow or tracking-to-control pipelines; fairness and breadth of comparisons (including non-generative planning baselines) can be improved.

- Trace-to-policy integration: The work demonstrates a minimal controller; how to integrate trace predictions with modern learned policies, model-predictive control, or differentiable planners—and the resulting gains—remains unexplored.

- Data curation noise and bias: Despite filtering, residual suboptimal/erroneous demonstrations persist; their prevalence, effect on performance, and scalable data-cleaning strategies (e.g., confidence-based selection, weak supervision) are not quantified.

- Robustness to sensor modality gaps: Training uses estimated depth for videos; inference uses RGB-D sensors; the impact of domain gaps (e.g., sensor noise, missing depth, specular surfaces) and strategies like self-supervised adaptation are not studied.

- Multi-view and calibration: The pipeline picks a reference view per clip; how multi-view data (when available) or partial calibration could improve metric consistency and robustness is left unexplored.

- Evaluation metrics beyond success rate: There is no reporting on trajectory fidelity (e.g., path error, smoothness), contact timing, or energy/time efficiency; richer metrics would better diagnose where the model helps or fails.

- Scaling laws and compute: Training cost, model scaling behavior (parameters vs. performance), and data scaling curves (dataset size vs. transfer) are not provided, limiting guidance for future scaling.

Glossary

- 3D motion prior: A learned prior over plausible 3D movements that helps models generalize to new tasks and scenes. "a transferable 3D motion prior that adapts efficiently"

- 3D point tracking: Estimating the trajectories of points in three dimensions across video frames. "\subsection{3D Point Tracking with Camera Pose and Depth Prediction}"

- 3D transformer: A transformer architecture operating over spatiotemporal tokens for 3D data. "CogVideoX's~\cite{yang2024cogvideox} 3D transformer"

- 3D trace-space: A compact representation of scene motion as trajectories of 3D points, abstracting away appearance. "a compact 3D ``trace-space'' of scene-level trajectories"

- Adaptive LayerNorms: Layer normalization parameters modulated by conditioning signals to fuse information. "Adaptive LayerNorms applied separately to contextual input and latent trace tokens"

- Affordance: The potential actions an agent can perform with an object; here, often incorrectly hallucinated by pixel models. "Video-based models can hallucinate geometry or affordance."

- Arc-length reparameterization: Resampling a curve based on cumulative path length to normalize speed. "reparameterize by normalized arc-length parameter"

- Bimanual robot manipulation: Tasks involving coordinated control of two robotic arms. "bimanual robot manipulation"

- Camera extrinsics: Parameters describing a camera’s position and orientation relative to the world. "estimated camera extrinsics"

- Camera intrinsics: Parameters defining a camera’s internal geometry (focal length, principal point, etc.). "estimated camera intrinsics"

- Camera-motion compensation: Adjusting data to remove or account for camera movement. "TraceForge compensates camera motion"

- CogVideoX: A large video-generation transformer backbone adapted here for trace prediction. "a CogVideoX-based flow model"

- CoTracker3: A point-tracking model used to obtain consistent tracks across frames. "CoTracker3 as the point tracker"

- Cross-embodiment: Learning that transfers across different agent bodies (e.g., humans and robots). "cross-embodiment, cross-environment, and cross-task videos"

- Depth map: An image where each pixel encodes distance from the camera to the scene. "depth maps"

- DINOv3: A self-supervised vision transformer producing geometry-aware visual features. "DINOv3~\cite{simeoni2025dinov3}: A self-supervised vision transformer"

- Egocentric: First-person viewpoints where the camera moves with the actor. "spanning tabletop, egocentric, and in-the-wild footage"

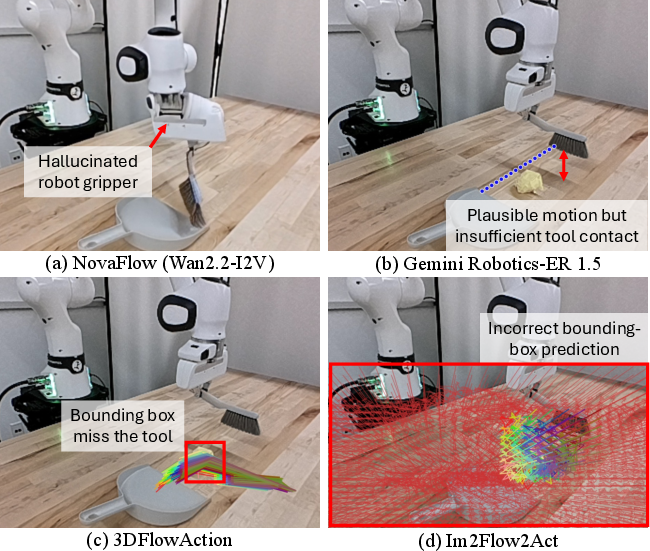

- Embodied world model: A predictive model tailored to agents interacting with the physical world. "Failure cases of existing embodied world models."

- Embodiment: The physical form and kinematics of an agent. "differences in embodiment, camera, and environment"

- Embodiment-agnostic: Not specific to any single robot or body, applicable across embodiments. "embodiment-agnostic policy"

- End-effector: The tool or gripper at the end of a robot arm that interacts with objects. "the motion of manipulated objects and end-effectors admits a shared, scene-centric 3D structure"

- Flow-based world model: A generative model that learns a velocity field to map noise to data for future prediction. "a flow-based world model that predicts future 3D motion trajectories"

- Gaussian noise: Random noise with a normal distribution used in generative modeling. "is Gaussian noise"

- Heuristic filtering: Rule-based post-processing that may introduce errors; avoided by the method. "without heuristic filtering or bounding boxes"

- Inverse kinematics: Computing joint angles that achieve desired end-effector positions/trajectories. "we apply inverse kinematics to map predicted 3D traces to robot joint commands"

- Keypoints: Selected points (often on a grid) tracked to represent scene motion. "a uniform grid of keypoints"

- Kinematics: The paper of motion without considering forces; differences across embodiments affect transfer. "embodiments differ in kinematics and scale"

- Linear interpolation ODE: An ordinary differential equation corresponding to a linear schedule between noise and data. "we implement a linear interpolation ODE"

- ODE integration: Numerically solving an ordinary differential equation to generate samples or trajectories. "via 100-step ODE integration"

- Patchification: Grouping neighboring elements into patches to form tokens for transformer processing. "We apply spatial patchification with patch size "

- Prismatic VLM: A multi-encoder fusion strategy combining diverse visual and text features. "employs a Prismatic-VLM multi-encoder fusion strategy"

- Reference camera frame: A fixed camera coordinate system used to express all traces consistently. "We designate the reference camera frame as $\mathrm{cam}_{\mathrm{ref}$"

- Screen-aligned 3D traces: Traces represented as image-plane coordinates with depth, aligned to the reference view. "compose the pixel coordinates and depth values as screen-aligned 3D traces"

- Segmentation masks: Pixel-wise labels isolating objects, used by some baselines. "which relies on segmentation masks"

- SigLIP: A vision-LLM producing semantically aligned visual features. "SigLIP: A vision-LLM (SigLIP-Base-Patch16-384)"

- Speed retargeting: Normalizing demonstration speeds so motions are comparable across embodiments. "applies speed retargeting to normalize embodiment-dependent motion"

- Stochastic Interpolant framework: A unifying framework for diffusion/flow models using data–noise interpolations. "We adopt the Stochastic Interpolant framework"

- T5-base: A transformer-based text encoder used to embed task instructions. "a frozen T5-base encoder"

- TAPIP3D: A model for tracking arbitrary points in persistent 3D geometry. "we adopt TAPIP3D~\cite{zhang2025tapip3dtrackingpointpersistent} as the 3D tracking model"

- TraceForge: The data pipeline that converts diverse videos into consistent 3D traces for training. "TraceForge provides the structured training signal"

- TraceGen: The proposed world model that predicts future motion in 3D trace-space. "TraceGen, a world model that predicts future motion in trace-space"

- Velocity field: A learned function predicting the instantaneous change guiding samples from noise to data. "The framework learns a velocity field"

- Vision-LLM (VLM): A model jointly trained on images and text for multimodal understanding. "Using a VLM, we produce three complementary instructions"

- World model: A predictive model of environment dynamics used for planning and control. "We present \tracegenlogo TraceGen, a world model that predicts future motion in trace-space"

- World-to-camera Transformation: Transforming world-coordinate traces into a camera’s coordinate/frame for consistency. "\subsection{World-to-camera Transformation}"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are applications that can be deployed now, leveraging the paper’s 3D trace-space world model (TraceGen) and data pipeline (TraceForge). Each item includes sector links, potential tools/workflows, and key assumptions or dependencies.

- Few-shot robot task rollout for assembly, packaging, and pick-and-place

- Sectors: manufacturing, logistics/warehouses, robotics software

- What you deploy: A “trace-space planner” integrating TraceGen with inverse kinematics (IK) in an existing ROS stack to adapt a robot to new SKUs or layouts using ~5 short videos.

- Workflow:

- 1) Record five quick demonstrations (robot-to-robot or human-to-robot via phone).

- 2) Run TraceForge to convert videos into consistent 3D traces with speed retargeting and camera compensation.

- 3) Fine-tune TraceGen and execute traces via IK.

- Tools/products: TraceGen inference module; TraceForge data engine; “TraceKit” ROS plugin for trace-to-IK control.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to RGB-D or reliable monocular depth prediction; accurate IK and safety interlocks; sufficient viewpoint coverage; tasks similar to those validated (tabletop manipulation). Performance benefits (80% success, >50× faster than video generators) rely on warm-up demos and the Franka-like arm kinematics.

- Phone-to-robot “teach by showing” for home service tasks (e.g., tidying, placing items, sweeping)

- Sectors: consumer robotics, smart home, assistive tech

- What you deploy: A lightweight smartphone app to capture 3–4 s demos and a backend service that runs TraceForge + TraceGen to adapt a home robot.

- Workflow: User records five handheld videos; cloud service reconstructs 3D traces; TraceGen fine-tunes and returns executable trajectories; local controller maps traces to robot actions.

- Tools/products: “TraceForge Cloud” for demo-to-trace conversion; home robot SDK implementing trace-to-action; simple calibration-free onboarding.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable RGB-D sensing or robust monocular depth; safe execution policies; tasks remain within reach and manipulation capabilities; current success rates (~67.5%) shown for simple tabletop tasks.

- Cross-embodiment dataset bootstrapping and benchmarking for research groups

- Sectors: academia, open-source robotics, education

- What you deploy: TraceForge to convert existing human/robot video datasets (e.g., EPIC-KITCHENS, SSV2) into consistent 3D trace corpora for training and benchmarking cross-embodiment learning.

- Workflow: Batch process datasets with TraceForge; pair traces with language instructions; train TraceGen or similar models; evaluate few-shot adaptation across robots and tasks.

- Tools/products: Dataset curation scripts; “TraceHub” for sharing trace-space datasets; unified trace-space evaluation suite.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Rights to reuse source datasets; adequate motion, depth, and pose estimation quality; clear task segmentation.

- Privacy-preserving motion sharing in robotics data ecosystems

- Sectors: policy/compliance, data governance, robotics platforms

- What you deploy: Policies and tooling to share trace-space (3D trajectories) instead of raw videos, mitigating PII exposure while keeping actionable motion signals.

- Workflow: Transform internal demos to trace-space before external sharing; enforce trace-only distribution in collaborations and competitions; retain raw video internally for QA.

- Tools/products: “TraceCheck” privacy transformer; compliance templates referencing trace-space abstractions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Trace-space sufficiency for downstream training/analysis; legal acceptance of trajectory-centric anonymization.

- Real-time planning for control stacks with limited compute

- Sectors: embedded robotics, industrial automation

- What you deploy: TraceGen as a compact inference module, replacing pixel-space video generation in planning loops.

- Workflow: Integrate TraceGen as a world model that outputs scene-level 3D motion; run closed-loop planning at the edge (jetson-class devices) with trace-to-action controllers.

- Tools/products: Optimized TraceGen runtime; trace-space MPC wrappers; ROS nodes for streaming traces.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Controller compatibility (IK or tracking-based execution); reliable perception; task dynamics within current temporal/horizon limits.

- Motion analytics and ergonomics from in-the-wild videos

- Sectors: sports analytics, industrial ergonomics, education

- What you deploy: TraceForge to extract 3D motion traces from videos for analysis (e.g., coaching, ergonomics reviews, movement comparisons).

- Workflow: Upload videos; derive screen-aligned 3D traces; visualize trajectory patterns and speed-normalized profiles; compare across individuals or sessions.

- Tools/products: “TraceViz” analytics dashboards; standardized trace export formats for CAD/simulation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Depth and pose estimation quality; non-contact analysis only (no direct control in this use case); adequate camera coverage of motion.

- Quality assurance (QA) gates for robot trajectories

- Sectors: industrial robotics, safety engineering

- What you deploy: A trace-level pre-execution check to detect physically implausible or unsafe trajectories before commanding the robot.

- Workflow: Run TraceGen to predict the next motion; evaluate constraints (workspace, collision, velocity profiles); abort or adjust if violations are detected.

- Tools/products: Trace-space validators; safety policies integrated with trace generation; simulators for dry runs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable collision models; workspace maps; trace-space predictive accuracy in the relevant environment.

- Cost reduction in robot training by replacing detector-heavy pipelines

- Sectors: robotics software, startups

- What you deploy: TraceGen to learn scene-level motion without object detectors or heuristic filtering, reducing engineering complexity and error cascades.

- Workflow: Train on trace triplets; deploy trace-based execution; drop multi-stage detection/tracking stacks; monitor performance and add warm-up demos as needed.

- Tools/products: “Detector-free” motion modules; trace-only training recipes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Tasks where fine-grained object semantics are less critical than geometry; acceptable performance without detectors; fallback strategies for edge cases.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, safety validation, or broader ecosystem development before practical deployment.

- Generalist household manipulation beyond tabletop

- Sectors: consumer robotics, smart home

- Vision: Teach complex tasks (laundry folding, cooking prep, tidying in clutter) from a handful of human videos across rooms and appliances.

- Required advances: Richer controllers (compliance, tactile feedback), multi-view/moving-camera robustness, stronger zero-shot reliability, safety certification.

- Dependencies: Internet-scale trace datasets, better filtering of exploratory/corrective motions, improved trajectory precision.

- Clinical rehabilitation and assistive robotics trained from therapist videos

- Sectors: healthcare, assistive technology

- Vision: Robots learn physical therapy routines or ADLs (activities of daily living) from therapist demonstrations recorded on phones.

- Required advances: Medical-grade safety and oversight, embodiment-specific kinematic mapping to human motions, personalized adaptation, regulatory clearance.

- Dependencies: High-fidelity motion capture (multimodal sensors), validated risk controls, data governance and consent frameworks.

- Cross-domain manipulation for construction, agriculture, and field robotics

- Sectors: construction, agriculture, energy maintenance

- Vision: Few-shot adaptation across diverse embodiments (mobile bases, different manipulators) and outdoor scenes with moving cameras and variable lighting/weather.

- Required advances: Robust depth/pose under adverse conditions, domain randomization for traces, mapping traces to heterogeneous action spaces.

- Dependencies: Larger cross-embodiment datasets including non-lab conditions; standardized trace-to-action interfaces across robot types.

- Humanoid robot training from large-scale human video corpora

- Sectors: robotics (humanoids), education

- Vision: Use TraceGen-like models to learn human-like skills from internet-scale human videos, leveraging shared 3D motion priors for transfer.

- Required advances: Reliable kinematic retargeting from human traces to varied humanoid morphologies, contact-rich manipulation modeling, balance and whole-body control.

- Dependencies: Standards for trace-space representations of full-body motion; multi-contact controllers; safety constraints.

- Standardization of “trace-space” as a data interchange format

- Sectors: policy/standards, research ecosystems, industry consortia

- Vision: Create open standards for trajectory representations, sampling schedules, camera alignment conventions, and metadata to enable trace-space sharing and tooling interoperability.

- Required advances: Consensus on schemas and APIs, validation protocols, provenance tracking.

- Dependencies: Multi-stakeholder collaboration (academia, industry, standards bodies), benchmark suites.

- Cloud adaptation and “TraceOps” services

- Sectors: SaaS for robotics, platform providers

- Vision: Managed services that turn a few customer videos into robot-ready trace policies, with continuous improvement and fleet-wide updates.

- Required advances: Scalable trace extraction and training pipelines, customer-specific domain adaptation, MLOps for safety and rollback.

- Dependencies: Data privacy guarantees (trace-only); edge deployment toolchains; monitoring for drift and failures.

- Multi-robot coordination via shared trace plans

- Sectors: manufacturing, logistics

- Vision: Coordinated tasks where robots exchange and align trace-space plans to avoid conflicts and optimize throughput.

- Required advances: Joint optimization in trace-space; collision avoidance between traces; scheduling and negotiation protocols.

- Dependencies: Real-time communications; shared map/state; trace-level MPC.

- Edge-native trace inference for small form-factor robots and IoT

- Sectors: embedded systems, consumer devices

- Vision: Deploy compact trace models on microcontrollers or low-power SOCs for real-time manipulation or motion guidance.

- Required advances: Model compression, hardware acceleration for flow-based decoders, robust perception pipelines with minimal sensors.

- Dependencies: Co-design with hardware; quantization-aware training; thermal and latency constraints.

- Motion summarization for AR/VR, sports, and media production

- Sectors: media tech, sports science, education

- Vision: Use screen-aligned 3D traces to drive overlays, tutorials, or motion comparisons in AR/VR and coaching tools.

- Required advances: High-accuracy trace extraction in unconstrained scenes; user-friendly visualization; integration with 3D engines.

- Dependencies: Improved TAPIP3D/point tracking under occlusion; standardized trace-to-AV pipelines.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Perception quality: Reliable camera pose and depth estimation (e.g., TAPIP3D, CoTracker3, VGGT); handheld videos may introduce noise and require robust compensation.

- Controller compatibility: Mapping trace-space to robot actions (IK, tracking controllers) must respect kinematics, collision constraints, and safety.

- Data quality and curation: TraceForge mitigates camera motion and retargets speed, but suboptimal demonstrations (exploratory/corrective motions) still affect supervision.

- Generalization limits: The paper reports strong few-shot adaptation for tabletop tasks; zero-shot performance and complex, contact-rich behaviors remain open challenges.

- Compute and latency: TraceGen offers large speedups versus video generators; edge deployments may need further optimization and compression.

- Compliance and safety: For consumer and clinical scenarios, rigorous safety validation, privacy-preserving data practices, and regulatory approvals are required.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.