- The paper introduces a novel self-supervised framework that infers latent mechanical properties from sequential tactile data.

- It integrates robotic data acquisition and advanced encoder-decoder architectures to predict force maps and MRI images with high accuracy.

- The study demonstrates improved lump detection and classification, outperforming traditional force mapping methods in both simulation and experiments.

Artificial Palpation via Self-Supervised Representation Learning on Soft Bodies

Introduction and Motivation

The study "Toward Artificial Palpation: Representation Learning of Touch on Soft Bodies" (2511.16596) presents a systematic exploration of machine-based palpation as an inference problem, distinct from conventional tactile imaging or elastography. Traditional tactile imaging approaches often rely on direct force mapping from sensor arrays pressed against soft tissue, limiting interpretability and inference to coarse mechanical properties like stiffness. This work is motivated by the clinical significance of palpation in breast cancer detection, combined with the hypothesis that data-driven representation learning can surpass simple force maps by capturing temporally resolved, object-specific mechanical interactions from sequential tactile data.

The authors formulate artificial palpation as a self-supervised learning task, aiming to encode tactile measurements into representations that enable downstream tasks such as tactile imaging, change detection, and object classification. The centerpiece is a modular pipeline incorporating robotic data acquisition, unprecedented breast phantom fabrication with ground-truth MRI imagery, advanced encoder-decoder architectures, and rigorous evaluation protocols.

Figure 1: Overview of the proof-of-concept for artificial breast palpation, including phantom fabrication, robotic tactile sensing, encoder-decoder architecture for tactile representation, and downstream training for imaging and change detection.

Methodology

The artificial palpation problem is mathematically defined as inferring latent object properties M (representing mechanical and structural attributes) given a sequence of tactile measurements ft at poses xt. The approach presumes that M is inaccessible, but ground-truth observations (e.g., MRI I) are available for a subset of objects. The self-supervised paradigm is necessitated by the cost asymmetry between collecting labeled (paired with I) and unlabeled (palpation-only) data.

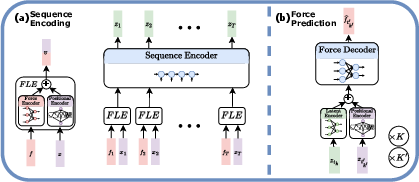

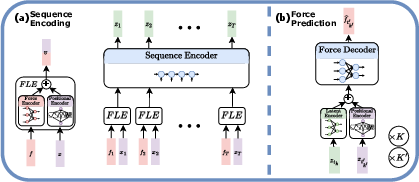

Encoder-Decoder Representation Learning

The system's core is an encoder-decoder neural network optimized for force prediction. For each tactile measurement and pose, the forces are encoded using an MLP and the positions via sinusoidal positional encoding (PE), termed the Force Location Encoder (FLE). Sequential embeddings are processed with a GRU, producing latent states zt. The decoder, conditioned on these latent states and desired poses, predicts force readings at arbitrary timepoints, training with mean squared error reconstruction loss over randomly subsampled timestep pairs to control computational complexity.

Figure 2: Tactile sequence representation: Measurement+pose pairs are encoded by FLE, sequenced via GRU, and decoded for force prediction at arbitrary positions.

Self-supervised pretraining leverages large tactile datasets to create representations that support supervised downstream regression, notably tactile imaging (MRI prediction) and change detection (lump size estimation).

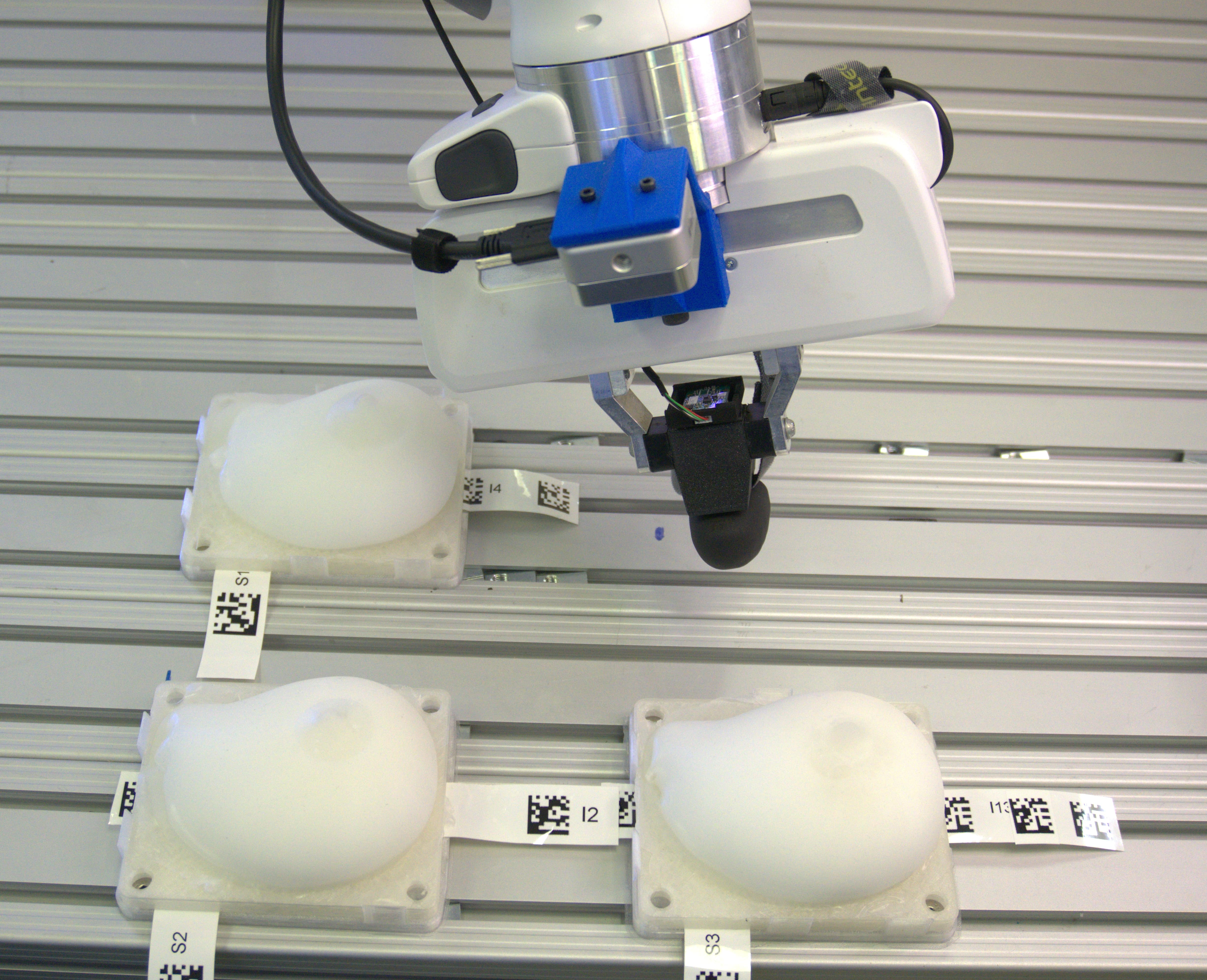

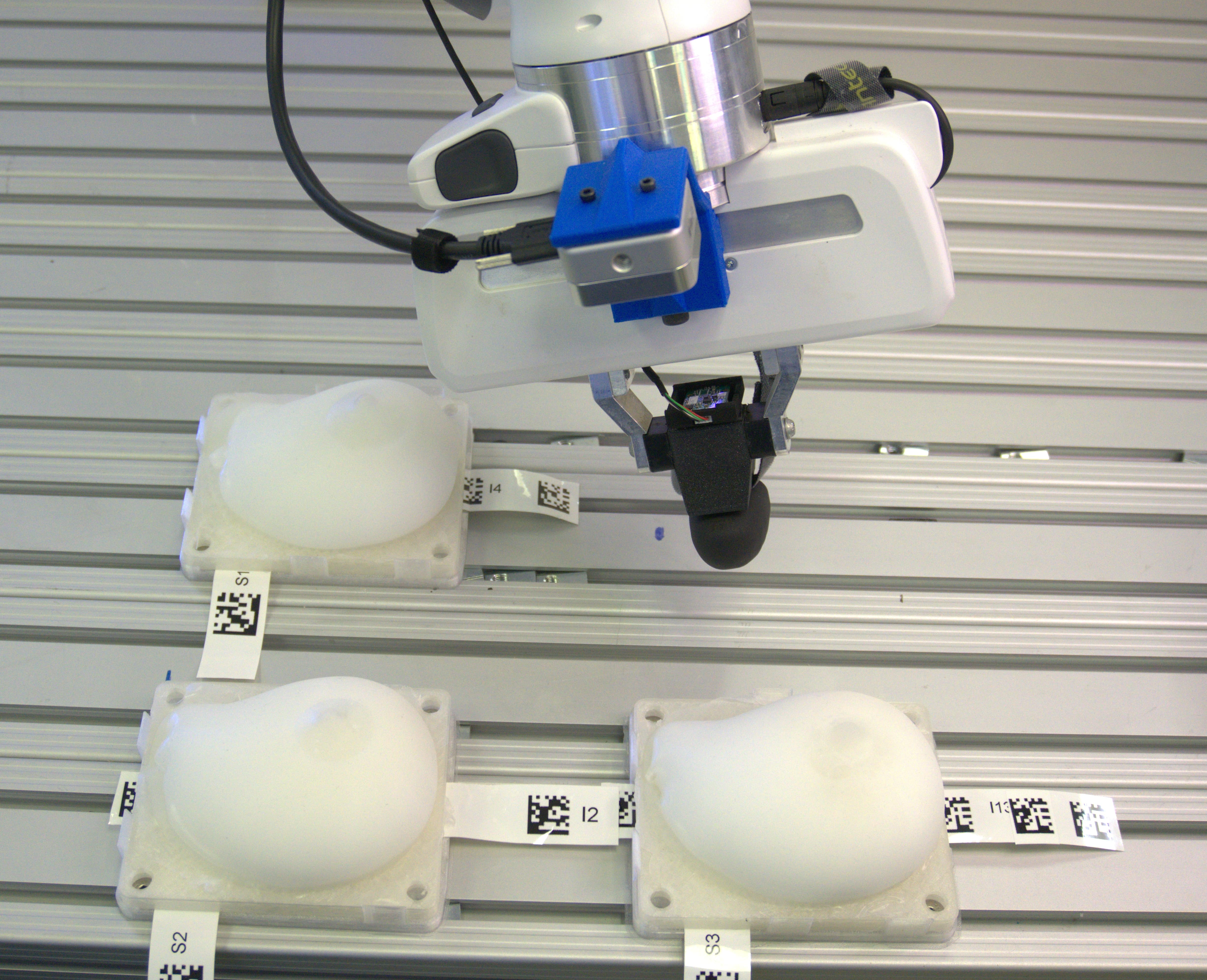

Modular Phantom Fabrication and Data Acquisition

A major technical contribution is the design and manufacturing of breast phantoms with parametric modularity. The system allows combinatorial assembly of shells and inserts, each with variable hydrogel composition and lump placements/sizes. Data acquisition is automated using a Franka Emika Panda arm and XELA uSkin sensor, performing thousands of controlled palpation “pokes” with precise pose/force trajectories. Ground-truth is obtained by scanning phantoms in clinical-grade MRI, ensuring that imaging predictions are both realistic and challenging.

Figure 3: Automated robotic data collection setup with phantom, robotic arm, tactile sensor, and integrated QR code tracking.

Downstream Task Networks

For tactile imaging, the authors utilize a flow matching-inspired conditional image generation network. The final latent representation zT for a palpation sequence is mapped, together with sampled Gaussian noise, to pixelwise probability logits over processed MRI slices, trained with per-pixel cross-entropy. The architecture is modular and can be extended to volumetric imaging. For change detection, lump size estimation from predicted images is used as a binary classifier for lump growth.

Experimental Results

Simulation Benchmarks

In PalpationSim, a custom FEM environment, the approach demonstrates strong image reconstruction fidelity and illuminates the crucial role of self-supervised pretraining, trajectory permutation augmentation, and data scaling. F1 scores for lump localization and size in simulation surpass force map baselines, with clear benefit from model-driven tactile representations.

Real-World Tactile Imaging and Change Detection

Using ∼60,000 pokes over hundreds of phantom combinations:

- The image prediction network achieves lump size errors of 23% and center-of-mass (CoM) localization errors of $2.4$mm, with F1 score 74.4% using the full dataset. These errors degrade gracefully when training data is reduced.

- Baseline approaches relying on force map aggregation, even with advanced kernel density estimation, underperform (size error 46.6%, CoM error $5.3$mm, F1 47.3%) compared to learned representations.

- The learned representation consistently improves with unsupervised data addition; doubling pretraining data yield an 11% increase in F1 score without extra labels, validating the scalable, data-driven paradigm.

Figure 4: Real-world tactile imaging: CAD design, ground-truth MRI, model predictions, and force map visualizations across several phantom configurations.

Change detection accuracy was compared against human performance in a controlled study:

- Robotic classifier recall: $0.82$, false alarm rate: $0.19$

- Human: recall $0.62$, false alarm rate $0.32$

This is a notable result given the XELA sensor's spatial resolution is orders of magnitude below human finger density.

Additional Downstream Tasks

Shell classification using the learned representation achieves 99.6±0.7% accuracy, highlighting sensitivity to minor manufacturing variations unreflected in MRI imagery.

Implications and Future Directions

The demonstrated pipeline affirms that self-supervised tactile representation learning on soft bodies encodes object-intrinsic mechanical structure sufficient for detailed downstream inference, including image prediction and change quantification. The system's performance is hardware-agnostic and improves with dataset size, unlike conventional force map or stiffness-based approaches.

Key implications:

- Scalability and Foundation Models: The positive scaling with unsupervised data points toward the feasibility of foundational models in tactile perception, analogous to vision or LLMs, particularly if cross-domain tactile datasets are aggregated.

- Clinical Applicability: Transitioning to human subjects would require extensions in data collection, pose estimation, active or human-like sensing, and handling of complex tissue structures observable in real MRIs, as noted in the discussion. The approach is complementary to existing clinical workflows and could provide precise, patient-specific tactile change monitoring.

- Technological and Sociological Considerations: Real-world deployment necessitates advancements in low-cost tactile sensor arrays, robust trajectory planning, and system miniaturization. The preliminary acceptance study for robotic screening is encouraging.

- Open Data and Reproducibility: The modular phantom design, automated setup, and open data protocols set a methodological standard for reproducible research in tactile AI.

Conclusion

This work establishes a principled framework and empirical validation for self-supervised representation learning in tactile palpation of soft bodies. Through a comprehensive pipeline, combining large-scale data acquisition, modular phantom fabrication, and advanced neural architectures, the study demonstrates that touch-based representations can support robust inference tasks – from lump detection and imaging to classification and change monitoring. The findings hold promise for clinical translation and foundational model development in tactile AI, subject to further exploration with real human data and more complex mechanical environments.