$π^{*}_{0.6}$: a VLA That Learns From Experience (2511.14759v2)

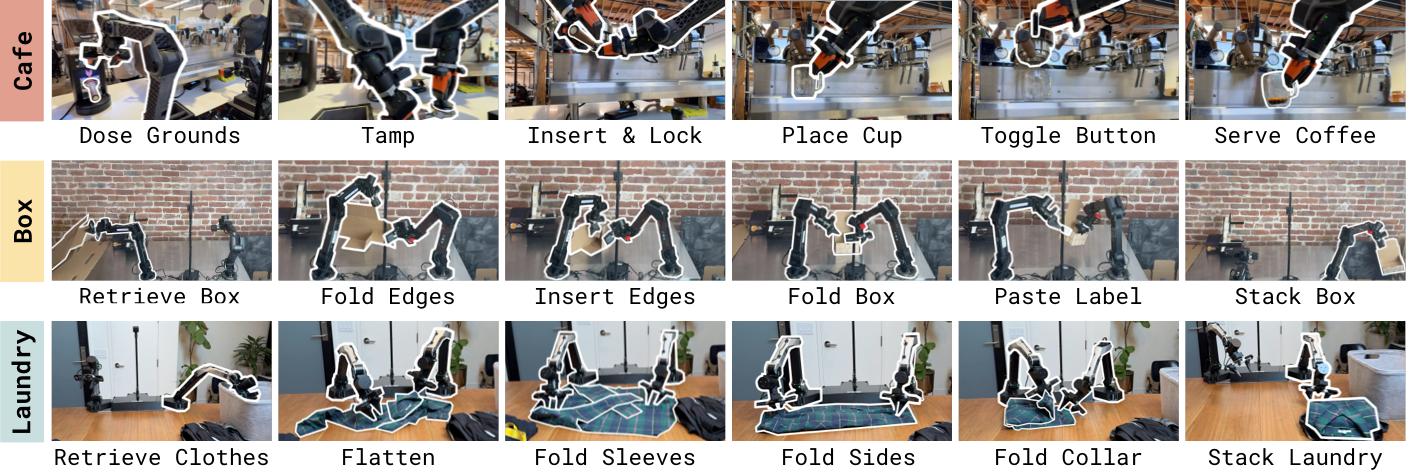

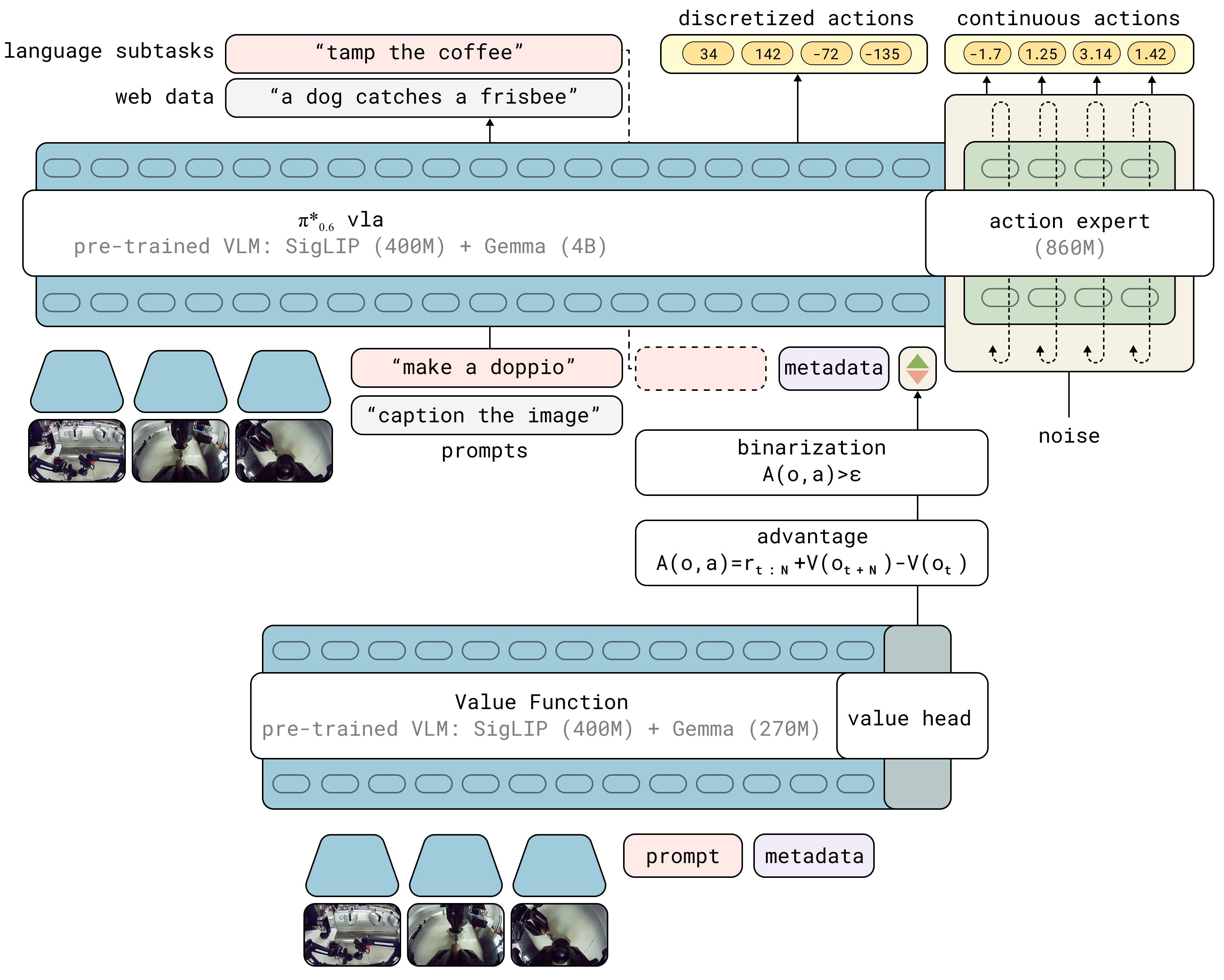

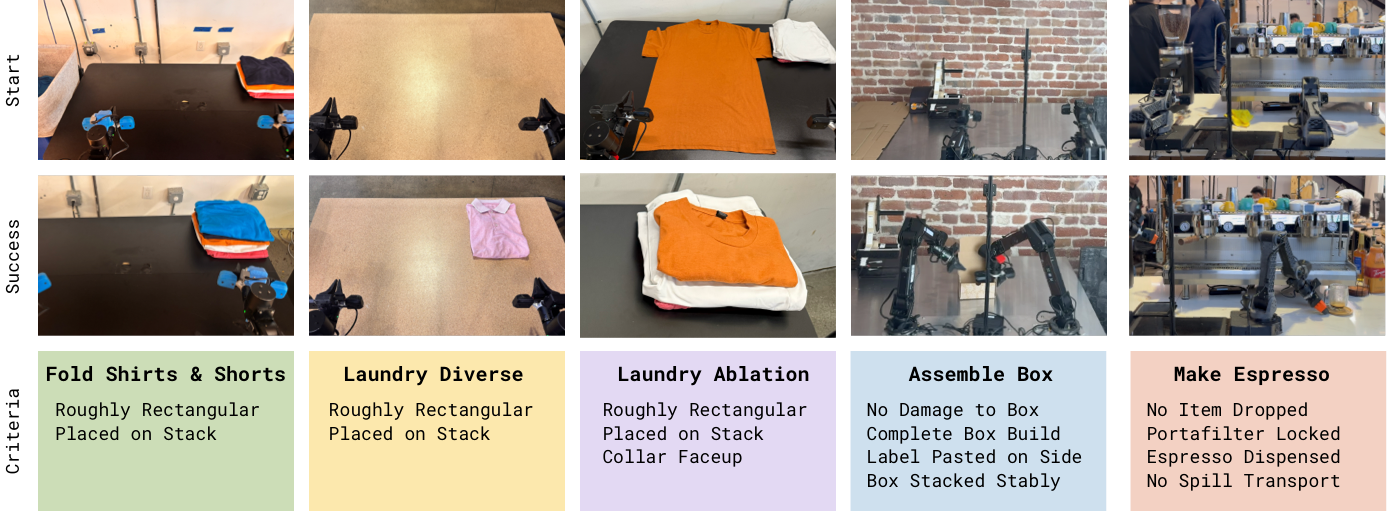

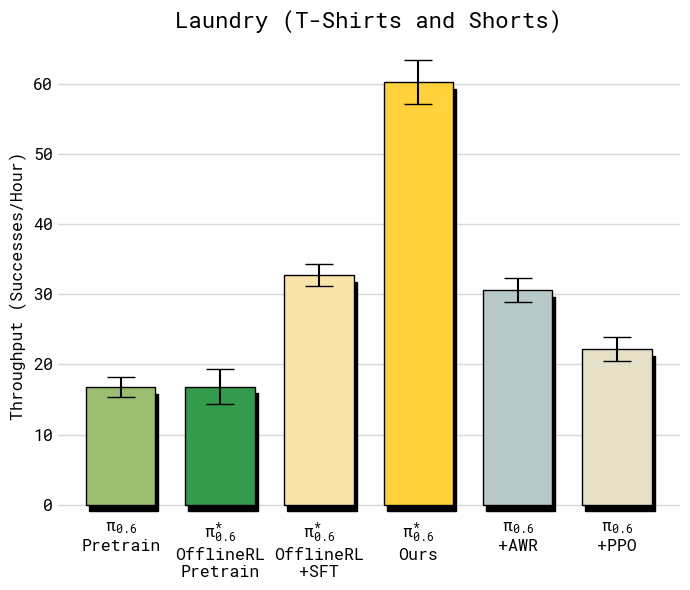

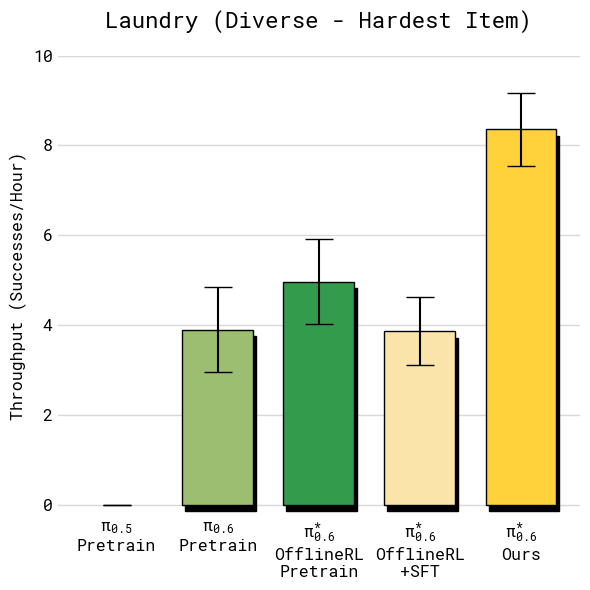

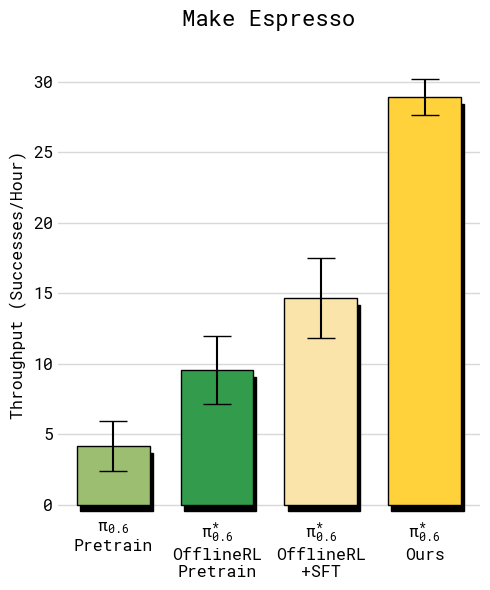

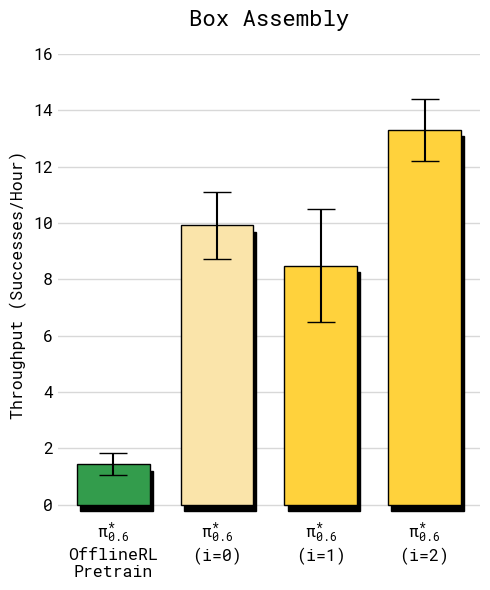

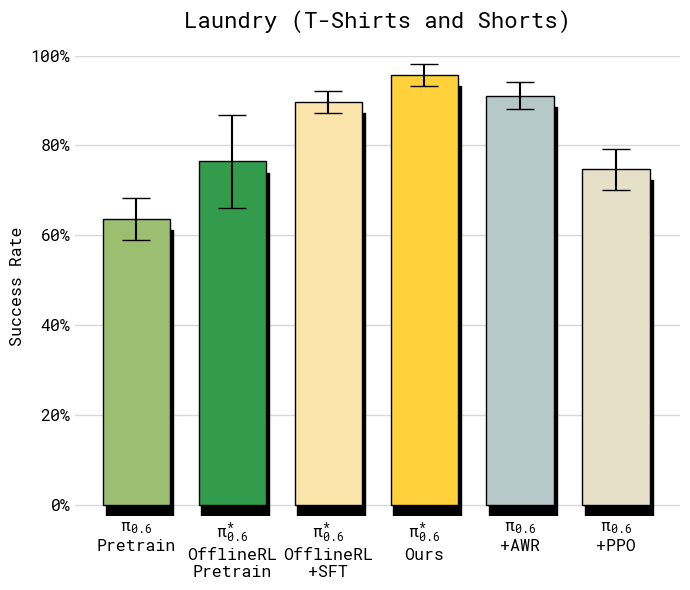

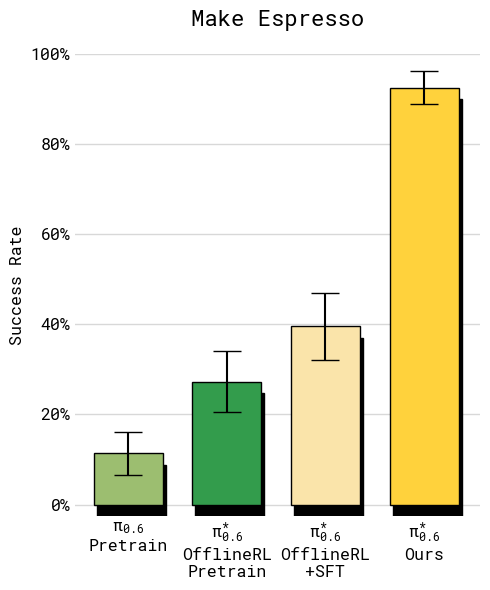

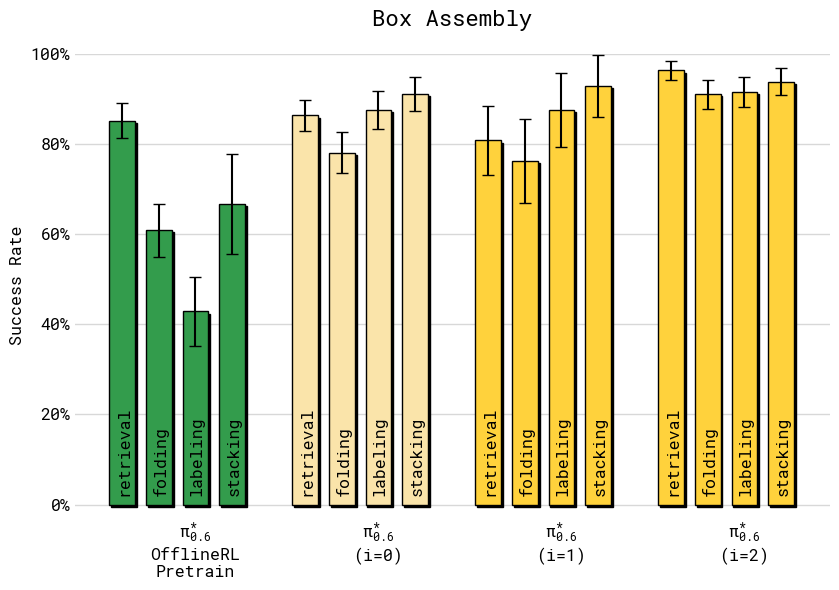

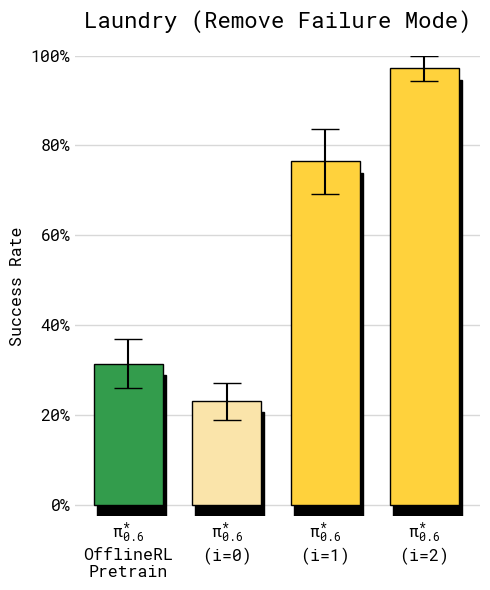

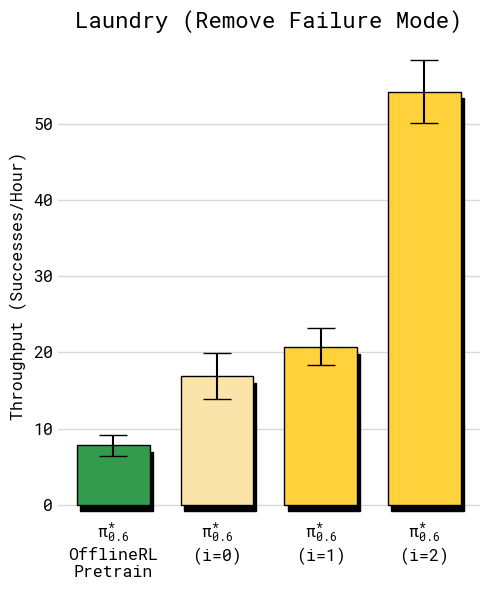

Abstract: We study how vision-language-action (VLA) models can improve through real-world deployments via reinforcement learning (RL). We present a general-purpose method, RL with Experience and Corrections via Advantage-conditioned Policies (RECAP), that provides for RL training of VLAs via advantage conditioning. Our method incorporates heterogeneous data into the self-improvement process, including demonstrations, data from on-policy collection, and expert teleoperated interventions provided during autonomous execution. RECAP starts by pre-training a generalist VLA with offline RL, which we call $π{*}_{0.6}$, that can then be specialized to attain high performance on downstream tasks through on-robot data collection. We show that the $π{*}_{0.6}$ model trained with the full RECAP method can fold laundry in real homes, reliably assemble boxes, and make espresso drinks using a professional espresso machine. On some of the hardest tasks, RECAP more than doubles task throughput and roughly halves the task failure rate.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper shows how to help robot “brains” get better by practicing in the real world with feedback. The robot brain is a Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model: it sees through cameras, understands text instructions, and moves its arms and hands. The new method, called “MethodName,” lets these models learn from experience using rewards (like a score for success) and human corrections, so they become faster and more reliable at tricky tasks such as folding laundry, assembling boxes, and making espresso.

What questions does the paper try to answer?

- Can a general robot model improve its skills by practicing in real homes and workplaces, not just from prerecorded examples?

- How can we safely and simply use reinforcement learning (RL) with big VLA models that understand language and control continuous motions?

- Does learning from a mix of data—human demonstrations, the robot’s own attempts, and human interventions—make the robot both faster and less likely to fail?

How did the researchers approach the problem?

Think of the method like training a sports team:

- First, the team learns basic plays from recorded drills (pretraining on demonstrations).

- Then they play real matches (robot attempts in the real world).

- A coach watches, keeps score, and occasionally steps in to correct big mistakes (human interventions).

- The team studies the games, learns which moves helped, and practices those more (advantage conditioning).

Here’s the idea in everyday terms:

Step 1: Collect experience

The robot runs the task and gets a simple “success or failure” label at the end of each try. Sometimes a human steps in mid-task to correct a mistake (for example, when the robot is about to drop the cup).

Step 2: Train a value function (the “judge”)

The value function is a learned “scorekeeper” and “fortune-teller”:

- It looks at what’s happening and predicts how close the robot is to finishing successfully (or if it’s heading toward failure).

- In plain terms: higher score means the robot is on track; lower score means trouble.

Step 3: Advantage conditioning (teach the robot which moves are better)

From the judge’s scores, the system computes an “advantage” for each action—like a thumbs-up if a move helped compared to average. The model then trains with an extra input that says “this action was good” or “not good.” Over time, it learns to prefer good actions and avoid bad ones.

Why this is clever:

- It uses all the collected data (good tries, bad tries, and human corrections), not just perfect demonstrations.

- It works well with modern action generators (like “flow matching”) used in big VLA models, avoiding complicated RL algorithms that can be hard to scale.

- Human corrections are treated as good examples, helping the robot recover from and avoid big mistakes.

What did they find?

The method made the robot significantly better on real, difficult tasks:

- Folding laundry, including diverse clothes like button-up shirts and towels

- Assembling cardboard boxes used in a factory

- Making espresso drinks with a professional machine (grinding, tamping, locking the portafilter, extracting shots, serving)

Key improvements:

- Throughput (successful tasks per hour) more than doubled on some of the hardest tasks.

- Failure rates roughly halved.

- Long, uninterrupted runs: for example, the robot made espresso for 13 hours straight and folded clothes in a new home for over 2 hours without stopping.

Why this matters:

- These tasks involve tricky, real-world challenges—deformable objects (cloth, cardboard), liquids (coffee), and multiple precise steps. Improving speed and reliability here is a big deal.

What’s the big picture impact?

- Practice makes perfect, for robots too: This work shows a practical way for general-purpose robot models to keep improving after they’re deployed, by learning from their own experience and simple feedback.

- Safer and more scalable learning: By mixing demonstrations, the robot’s attempts, and human corrections, the robot can improve without relying on fragile, hard-to-scale RL tricks.

- Toward useful robots in homes and factories: Faster, more reliable completion of real tasks means robots are closer to being truly helpful in everyday settings.

- A general recipe: The approach (pretrain + collect experience + value-judge + advantage conditioning) isn’t tied to one task. It can apply to many skills and robot types, making it a broadly useful way to train self-improving VLA models.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of unresolved issues that future researchers could target to strengthen, generalize, or stress-test the proposed method and model.

- Advantage estimation is based on a state value (distributional) Monte Carlo estimator rather than an action-conditional critic (Q-function), limiting policy improvement to dataset actions and preventing evaluation of counterfactual actions; how to incorporate off-policy, action-conditional critics for flow/diffusion VLAs without sacrificing scalability remains open.

- The choice of a binarized advantage indicator discards magnitude information; it is unclear whether conditioning on a calibrated continuous advantage (or multi-level bins) would improve sample efficiency, stability, or throughput.

- The task-specific threshold for “positive” advantage ( set to the 30th percentile) is heuristic; sensitivity analyses, automatic calibration across iterations, and adaptation to changing data distributions are not provided.

- The value function relies on an on-policy Monte Carlo estimator over heterogeneous behavior (demonstrations, prior policies, interventions), which can be biased under distribution shift; robustness to off-policy data and principled debiasing are not addressed.

- There is no uncertainty modeling or calibration of the value function across tasks with different horizons, failure modes, and success criteria; how to incorporate uncertainty-aware critics (e.g., ensembles, Bayesian heads) and use uncertainty for data selection or risk-aware control is unexplored.

- The reward is sparse and episode-level, encoding only time-to-success plus a large failure penalty; the effects of reward noise, ambiguity, and multi-objective trade-offs (speed vs. safety vs. quality) are not studied, nor are methods for learning from dense/subgoal rewards or preferences.

- The method assumes reliable success/failure labeling; real-world mislabels and stochastic outcomes are acknowledged but not modeled (e.g., via robust losses or label-noise mitigation).

- Human corrections are forced to be “positive” advantage (I_t=True) without accounting for imperfect or inconsistent interventions; quantifying intervention quality, frequency, and cost—and learning to selectively query or correct—remains open.

- The framework does not propose an active data collection strategy (e.g., exploration bonuses, uncertainty-guided rollouts, curriculum or prioritization); how to target scarce on-robot data to maximize improvement is unaddressed.

- The value function is re-finetuned from the pre-trained checkpoint each iteration rather than from the latest critic; the trade-offs (drift, stability, sample efficiency) and convergence criteria are not analyzed.

- The inference-time role of classifier-free guidance (β) is minimized via the advantage threshold, but there is no systematic paper of guidance weights, their interaction with action chunking, or effects on aggressiveness/safety.

- Action generation uses flow matching with chunked joint position control at 50 Hz; how chunk length, control modality (torque/impedance), and contact-rich dynamics affect learning and performance is not analyzed.

- The VLA’s high-level language/subtask predictions are used to condition action generation, but the reliability of language-conditioned planning (e.g., prompt mis-specification, hallucination) and its effect on RL training are not evaluated.

- Safety is not explicitly modeled (no risk-sensitive objectives, constraints, or safety critics); how to integrate safety costs, hazard detection, and intervention policies into the advantage-conditioned framework is an open question.

- The method improves specialists on specific tasks; whether multi-task, continual RL fine-tuning preserves generalist capabilities, avoids catastrophic forgetting, and enables cross-task transfer is not tested.

- The approach does not use the value function online for real-time guidance or planning; opportunities to integrate the critic at inference (e.g., lookahead, action scoring, or rollout selection) are unexplored.

- There is limited discussion of sample efficiency: how many autonomous episodes and interventions are needed per task, and how data scales with task complexity or difficulty.

- Scalability to different robot morphologies (beyond 6-DoF parallel-jaw bimanual arms), to mobile manipulation, or to tools requiring precise force/torque control is not demonstrated; generalization across hardware remains open.

- Throughput and success metrics do not capture product quality (e.g., espresso taste/temperature, fold neatness, box integrity) or downstream utility; richer task-specific metrics and validations are missing.

- The normalization of value targets to (-1, 0) per task using maximum episode length may be brittle under changing horizons or curriculum; adaptive normalization/calibration strategies are not explored.

- Handling long-horizon tasks (>10 minutes), interruptions, partial successes, and recoveries lacks formal treatment; structured subgoal rewards or hierarchical critics could be investigated.

- The training mixture weights (demo vs. autonomous vs. intervention) and recency weighting are fixed; systematic ablations on data weighting, replay prioritization, and retention of failed episodes are absent.

- Comparisons to strong off-policy RL baselines for continuous actions (e.g., CQL/TD3+BC/IQL variants compatible with diffusion/flow policies) are limited; rigorous baselines and controlled ablations are needed.

- The Markov assumption for observations is acknowledged as a simplification; there is no paper of longer temporal context, memory architectures, or state estimation effects on value/policy learning.

- Reset-free RL and autonomous recovery are not discussed; deployment practicality may depend on self-reset capabilities or minimal human oversight strategies.

- The method co-trains the value function with a small mixture of web data to “prevent overfitting,” but the interaction between web data and robot data (domain shift, spurious correlations) is not analyzed.

- The computational cost (training time, GPU hours, memory footprint) and engineering effort for pre-training and iterative RL are not reported; practicality for academic labs or industry deployments is unclear.

- The approach assumes availability of large-scale pre-training data across many robots; strategies for low-resource settings (few demos, limited hardware) are not presented.

- The influence of gripper compliance, perception latency, camera placement, and calibration errors on value/policy accuracy and throughput has not been quantified.

- No formal statistical analysis of stability across seeds, sites, or conditions is provided; reproducibility and robustness under environmental variability (lighting, clutter, human presence) remain open.

- It is unclear whether advantage conditioning helps mitigate compounding errors at test time without an explicit DAgger-like data aggregation policy; principled integration of DAgger with advantage conditioning is an open design space.

- Failure analysis is limited; a taxonomy of error modes (perception, grasp, sequencing), their evolution across iterations, and targeted RL strategies to eliminate specific failures (beyond the orange T-shirt example) would be valuable.

- Preference-based RL or reward learning from human feedback (e.g., pairwise comparisons, scalar judgments) is not integrated; this could address ambiguous success criteria or multi-objective trade-offs.

- The framework does not address sim-to-real transfer or how simulated RL could pretrain critics/policies for safer or cheaper iteration prior to real deployment.

Glossary

- Advantage conditioning: Conditioning a policy on an estimate of how much better an action is than expected, to bias learning toward improvements. "provides for RL training of VLAs via advantage conditioning."

- Advantage-conditioned policy extraction: A supervised policy learning approach that uses advantage signals as an input to extract an improved policy from off-policy data. "Our advantage-conditioned policy extraction method is based on a closely related but less well-known result:"

- Advantage-Weighted Regression (AWR): A policy learning method that performs weighted regression where weights depend on estimated advantages. "such as AWR~\citep{peng2019advantage,wangCRR,kostrikov2022offline}"

- Behavior policy: The policy that generated the dataset used for training or evaluation in off-policy/regularized RL. "behavior policy that collected the training data."

- Binarized advantage indicator: A binary input flag indicating whether an action’s advantage exceeds a threshold, used to condition the policy. "The VLA is conditioned on a binarized advantage indicator, obtained from a separate value function initialized from a pre-trained but smaller VLM model."

- Classifier-free guidance (CFG): A technique to steer generative models by combining conditional and unconditional predictions, often used to sharpen outputs. "as in classifier-free guidance (CFG)."

- Direct Preference Optimization (DPO): An RL-from-preferences method that directly optimizes policies from pairwise human preference data. "use direct preference optimization (DPO) to optimize pick-and-place skills from human preferences"

- Distributional value function: A value function that models a full distribution over returns rather than a single expected value. "we represent with a multi-task distributional value function"

- FAST tokenizer: A discretization scheme for continuous robot actions into tokens for language-model co-training. "the FAST tokenizer~\citep{pertsch2025fast}"

- Flow-based VLA: A VLA architecture whose action generation is parameterized via flow/diffusion models rather than simple parametric densities. "supports high-capacity diffusion and flow-based VLAs"

- Flow matching: A generative modeling approach that learns continuous-time transport maps to match data and noise distributions. "with an expressive flow matching VLA model."

- Flow matching loss: The training objective used to learn the flow field in flow matching, aligning noised and clean samples. "The continuous part of the log-likelihood cannot be evaluated exactly, and instead is trained via the flow matching loss"

- Flow-matching action expert: A specialized module that generates continuous low-level actions using flow matching within a larger VLA. "an flow-matching action-expert with stop gradient."

- Human-gated DAgger: An imitation-learning variant where a human intervenes to gate data collection and corrections, improving robustness. "human-gated DAgger~\cite{kelly2019hg,jang2022bc}"

- Improvement indicator (I): A binary variable indicating whether an action is expected to improve over a reference policy, derived from advantages. "We assume the improvement indicator follows a delta distribution"

- Knowledge Insulation (KI): A training procedure that co-trains discrete and continuous outputs while preventing interference via stop-gradient mechanisms. "which uses the Knowledge Insulation (KI) training procedure~\citep{driess2025knowledge}"

- Monte Carlo estimator: An estimator that uses sampled returns (or outcomes) directly, rather than bootstrapped targets, to learn value functions. "This is a Monte Carlo estimator for the value function of the policy represented by the dataset"

- Off-policy Q-function estimator: A critic that estimates action values using data generated by a different policy than the one being optimized. "less optimal than a more classic off-policy Q-function estimator"

- Offline RL: Reinforcement learning from a fixed dataset without further environment interaction during training. "pre-trains the VLA with offline RL"

- On-policy estimator: A critic or estimator trained using data generated by the current policy being evaluated/optimized. "this on-policy estimator is less optimal than a more classic off-policy Q-function estimator"

- Policy extraction: The process of deriving an improved policy from a learned value/advantage function and logged data. "This is called policy extraction."

- Policy gradient methods: RL algorithms that optimize policy parameters by ascending estimated gradients of expected return. "policy gradient methods (including regularized policy gradients and reparameterized gradients)"

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): A popular policy-gradient algorithm that constrains updates with a clipped objective or KL penalty. "the proximal policy optimization (PPO) algorithm"

- Regularized reinforcement learning: RL that augments return maximization with a penalty keeping the policy close to a reference distribution. "Regularized reinforcement learning."

- REINFORCE: A classic Monte Carlo policy gradient algorithm using sampled returns for gradient estimates. "use PPO and REINFORCE respectively"

- Residual policy: A policy that learns corrective actions added on top of a base policy’s outputs. "where RL either trains a residual policy"

- Stop gradient: A training operation that prevents gradients from flowing into certain parts of the model to avoid interference. "using a stop gradient to prevent the flow-matching action expert from impacting the rest of the model."

- Teleoperated interventions: Human corrective actions performed during robot execution to guide or correct behavior. "expert teleoperated interventions provided during autonomous execution"

- Time-to-completion value functions: Value estimators that predict remaining steps/time until task completion, used for long-horizon control. "with time-to-completion value functions to train VLAs"

- Vision-LLM (VLM): A model that jointly processes visual and textual inputs for multimodal understanding. "pre-trained VLM backbone"

- Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model: A robotics model that maps visual and language inputs to action outputs for embodied tasks. "vision-language-action (VLA) models"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now using the paper’s advantage-conditioned RL for VLAs, distributional value functions, and human-in-the-loop interventions. Each item lists sector, concrete use cases, potential tools/products/workflows, and assumptions/dependencies that affect feasibility.

- Manufacturing and logistics: automated box assembly cells Tools/Products: advantage-conditioned VLA specialist fine-tuned on box assembly; dual-arm workcell with base and wrist cameras; value-function-based monitoring to detect stalls/failures; intervention capture UI for operators; integration with label applicators and crate handling. Workflow: start from pre-trained generalist VLA; collect demonstrations; deploy with sparse success labels; iterate with autonomous rollouts plus targeted human corrections; update value function and policy. Dependencies: 6-DoF arms with parallel jaw grippers; reliable camera coverage; consistent box SKU set; safety interlocks; process tolerance for occasional corrections; compute for inference/training.

- Hospitality/retail: robotic espresso stations Tools/Products: “espresso skillpack” trained via advantage conditioning (grinding, tamping, locking portafilter, shot extraction, cup handling); telemetry to track throughput/time-to-completion; POS integration and customer-facing status UI; spill/cleanup routines. Workflow: pre-train, SFT on machine-specific demos, deploy with reward labels (drink delivered) and human-gated interventions; periodic RL fine-tuning to improve speed and robustness. Dependencies: machine compatibility (portafilter geometry, grinder interface); food safety/sanitation protocols; liquid-handling reliability; human oversight during initial deployment; clear success/failure labels.

- Commercial laundry and hospitality services: folding stations for diverse textiles Tools/Products: laundry folding specialist for towels, shirts, jeans, etc.; value-function visualization to identify failure modes; standardized “cloth handling” action library; stacking and sorting logic. Workflow: demonstration collection across item types; task-specific success criteria; iterative autonomous practice with occasional expert corrections (e.g., recovery from mis-flattened items); periodic advantage-conditioned updates. Dependencies: adequate table space; lighting and camera placement; item variability management (sizes, stiffness); throughput targets that tolerate iterative learning; clear success rules (fold correctness, collar orientation).

- Home robotics (early adopters and pilot programs): task-specific assistance Tools/Products: consumer-grade dual-arm setup or high-DoF single-arm; mobile app for labeling success and triggering interventions; on-device value function for safety pausing; curated household skill library (folding, simple drink prep). Workflow: homeowner provides a few demos; iterative self-improvement with guided corrections; periodic updates via cloud RLOps. Dependencies: hardware availability/cost; household safety requirements; data privacy for in-home video; user time to label and correct; compute budget for local inference.

- Research and education: RL-VLA starter kit and curriculum Tools/Products: reference implementation of advantage-conditioned policy extraction for flow-matching actions; distributional value function training; value visualization tools for failure analysis; synthetic benchmark tasks for cloth/liquid manipulation. Workflow: replicate the paper’s pipeline in lab courses; compare to policy-gradient PPO/REINFORCE baselines; paper data mixtures (demos vs interventions vs autonomous rollouts). Dependencies: robot access or high-fidelity simulation; compatible VLM backbone (e.g., Gemma family); lab safety protocols; compute for training.

- Robotics software vendors and SI partners: “experience-driven improvement” module Tools/Products: SDK for advantage-conditioned fine-tuning; reward/intervention data manager; value function monitoring service; dashboards for throughput/failure rate; task library packaging. Workflow: integrate with existing robot APIs (action heads, cameras); deploy iterative RL updates; provide compliance and audit logging. Dependencies: API standardization across arms/grippers; customers’ willingness to adopt human-in-the-loop processes; service-level agreements for retraining cadence.

- Operations and safety policy in robotics deployments Tools/Products: intervention logging standards; failure taxonomy tied to value function drops; rollback safeguards; operator training guides for human-gated DAgger. Workflow: define episode-level success labels; thresholds for pausing/resets; regular post-mortems using value function visualizations. Dependencies: workforce training; site-specific safety regulations; union or worker council agreements on augmentation protocols.

- Real-time quality assurance: value-function-based failure preemption Tools/Products: runtime monitors that trigger pauses or request operator help when predicted time-to-success worsens; configurable thresholds per task; alerting UI. Workflow: run value inference in parallel; define task-specific ε thresholds and actions-on-alert. Dependencies: calibration to minimize false positives/negatives; latency constraints; robust perception under occlusions.

Long-Term Applications

The following applications require further research, scaling, or productization. They benefit directly from the paper’s innovations but depend on broader advances in hardware robustness, safety, data infrastructure, and generalization.

- Healthcare and eldercare assistance Use cases: laundry, light tidying, drink/meal prep, assistive fetching. Tools/Products: broadly generalist VLA with advantage conditioning across many home tasks; safety-aware action heads; preference-conditioned reward learning; tactile sensing integration for safe contact. Dependencies: medical-grade safety certification; reliable manipulation of diverse household objects; privacy safeguards; long-duration autonomy; human factors validation.

- Warehousing and fulfillment: generalist packing/kitting with deformables/liquids Use cases: assembling kits, packing fragile or soft goods, sealing/taping, fluid containment. Tools/Products: skill libraries for multi-stage assembly; workflow planners that coordinate subtask text predictions and action chunks; fleet-level RLOps (data pipelines, value function retraining at scale). Dependencies: SKU diversity and long-tail handling; integration with WMS/ERP; cycle time targets; robust spill/failure recovery.

- Education at scale: classroom robots that “learn by practice” Use cases: STEM curricula with iterative RL; student feedback as reward signals; shared skill repositories. Tools/Products: classroom-safe robots; cloud-hosted value/policy updates; ethical policy frameworks. Dependencies: cost and maintenance; supervision ratios; data privacy; curriculum integration.

- Energy/utilities and field maintenance with mobile manipulators Use cases: valve turning, meter reading, simple repairs, tool use in unstructured outdoor environments. Tools/Products: extension of advantage-conditioned VLA to navigation + manipulation; off-policy Q-function variants for low-data regimes; reliability under weather and terrain. Dependencies: hardware ruggedization; safety in public spaces; regulatory approvals; long-horizon reward design.

- Cloud Robot Learning Ops (RLOps) platforms Use cases: managed services for collecting rewards/interventions, training value functions, deploying updated specialists, audit/compliance. Tools/Products: standardized APIs for robots; data governance; skill marketplaces; monitoring/rollback; multi-tenant scaling. Dependencies: cross-vendor interoperability; liability frameworks for learning in production; compute costs.

- Governance and standards for RL in public-facing automation Use cases: certification for reward labeling processes, intervention records, audit trails, incident response. Tools/Products: compliance checklists; standardized logs; third-party audits; performance reporting (throughput, failure rate, learning curves). Dependencies: regulatory consensus; insurance products that recognize learning systems; public communication and trust.

- Hardware roadmaps optimized for VLA-RL manipulation Use cases: end-effectors tailored to cloth handling, liquids, and fine dexterity; integrated wrist/base cameras; tactile and force sensing. Tools/Products: new grippers; sensor fusion stacks; self-cleaning mechanisms for liquid tasks. Dependencies: R&D investment; cost and durability; standardized mounts/interfaces.

- Cross-domain generalist home robots Use cases: mix of cleaning, cooking prep, laundry, organizing; voice or text prompting with self-improvement. Tools/Products: unified generalist model pre-trained on diverse tasks; on-device value function; safe exploration constraints; user-friendly reward labeling via apps. Dependencies: robust generalization; manageable failure rates; consumer pricing; UX and safety assurances.

- Advanced policy extraction methods for large VLAs Use cases: improving performance on long-horizon tasks without discarding suboptimal data; supporting diffusion/flow-matching action heads. Tools/Products: extensions to off-policy estimators; hybrid advantage-conditioning with learned preference models; theoretical guarantees for large models. Dependencies: algorithmic research; benchmarks; reproducible pipelines across labs and vendors.

Assumptions and Dependencies Common Across Applications

- Pre-trained generalist VLA with an action expert (flow-matching or diffusion) and a value function; availability of task-specific demonstrations.

- Sparse, episode-level reward labels that are accurate and timely; clear success criteria per task.

- Human-in-the-loop interventions during early iterations; operator training for effective corrections (human-gated DAgger).

- Hardware: multi-camera coverage (base + wrist), 6-DoF arms with parallel jaw grippers or equivalent end-effectors; 50 Hz control loops; safe workspace and interlocks.

- Compute for on-the-fly value inference and periodic fine-tuning; data pipelines for storing episodes, labels, and interventions.

- Task-dependent advantage threshold ε that is well-calibrated; monitoring to avoid drift over iterations; fallback/rollback mechanisms.

- Regulatory and safety compliance, especially for food handling, public deployments, and sensitive environments; privacy and data governance for video and logs.

These applications flow directly from the paper’s contributions: a scalable, iterated offline RL recipe for VLAs, advantage-conditioned policy extraction that works with large flow/diffusion action heads, and practical deployment with human feedback and interventions that demonstrably improves throughput and robustness in real tasks (laundry, box assembly, espresso).

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.