BFM-Zero: A Promptable Behavioral Foundation Model for Humanoid Control Using Unsupervised Reinforcement Learning (2511.04131v1)

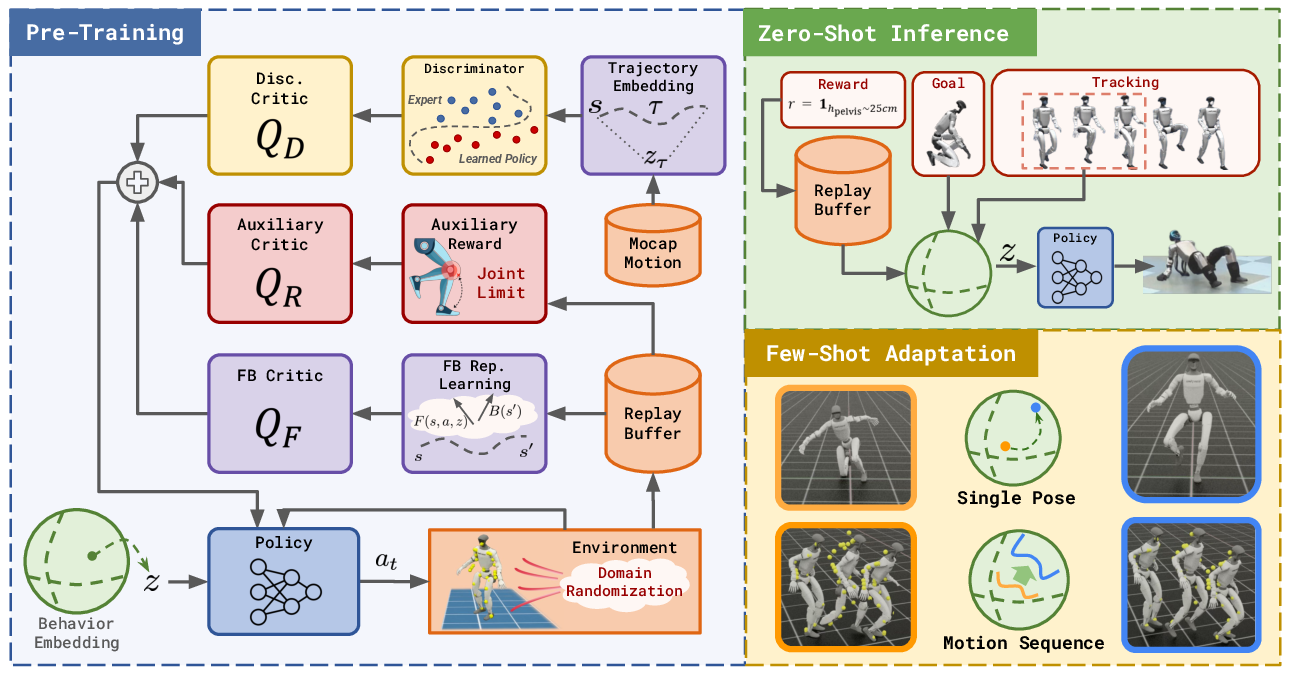

Abstract: Building Behavioral Foundation Models (BFMs) for humanoid robots has the potential to unify diverse control tasks under a single, promptable generalist policy. However, existing approaches are either exclusively deployed on simulated humanoid characters, or specialized to specific tasks such as tracking. We propose BFM-Zero, a framework that learns an effective shared latent representation that embeds motions, goals, and rewards into a common space, enabling a single policy to be prompted for multiple downstream tasks without retraining. This well-structured latent space in BFM-Zero enables versatile and robust whole-body skills on a Unitree G1 humanoid in the real world, via diverse inference methods, including zero-shot motion tracking, goal reaching, and reward optimization, and few-shot optimization-based adaptation. Unlike prior on-policy reinforcement learning (RL) frameworks, BFM-Zero builds upon recent advancements in unsupervised RL and Forward-Backward (FB) models, which offer an objective-centric, explainable, and smooth latent representation of whole-body motions. We further extend BFM-Zero with critical reward shaping, domain randomization, and history-dependent asymmetric learning to bridge the sim-to-real gap. Those key design choices are quantitatively ablated in simulation. A first-of-its-kind model, BFM-Zero establishes a step toward scalable, promptable behavioral foundation models for whole-body humanoid control.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper introduces BFM-Zero, a “behavioral foundation model” for a real humanoid robot. Think of it like a single, smart brain that can be “prompted” to do many different whole-body skills—walk, dance, reach a pose, or follow a new goal—without having to retrain it each time. The big idea is to learn a shared “skill space” where motions, goals, and rewards all live together, so the robot can understand different kinds of requests in a common way and act right away.

Key questions the paper asks

- Can we train one general control model for a humanoid that works for lots of tasks (not just one), and use it immediately after training—called “zero-shot”—without fine-tuning?

- Can that model be “prompted” in different ways (by a goal pose, a reward you want, or a motion clip) and still behave well?

- Will it be robust in the real world—handling pushes, slips, or worse—and still move naturally?

- If zero-shot isn’t perfect for a new situation, can we adapt it quickly with just a few trials (“few-shot”)?

To help with terms:

- Zero-shot: Use the model right away for a new task, no extra training.

- Few-shot: Do a small number of trials to improve performance on a new task.

How they did it: the approach in simple terms

They train in a simulator first, then deploy on a real Unitree G1 humanoid. The training uses unsupervised reinforcement learning (RL), which means the robot practices moving around and learns from broad objectives rather than hand-written, task-specific instructions. The key parts:

- A shared “skill space” (a latent space): Imagine a set of knobs (a vector called z). Turning these knobs changes the robot’s behavior. In this space:

- A motion clip (like a dance) becomes a “prompt” by turning the knobs a certain way.

- A goal pose (like a T-pose) also turns the knobs in another way.

- A reward (like “move forward while raising your arms”) becomes a different knob setting too.

- Because everything maps into the same space, the robot can respond to many kinds of instructions in one unified way.

- Forward-Backward representation (explained simply): The model learns two helpful “maps.”

- Forward map: “If I do this now, what kinds of future states will I visit?” Think of it as a map of likely futures.

- Backward map: “Which parts of the world matter for different tasks?” Think of it as a way to summarize what’s important across many goals.

- Combining these lets the robot quickly pick actions that make sense for whatever “prompt” it’s given.

- Learning to move like a human: They add a “style” component (a discriminator, like in GANs) that nudges the robot to move in a human-like way, using human motion data retargeted to the robot.

- Making it work in the real world:

- Asymmetric training: During training, some networks can see extra “privileged” information the real robot won’t have (like exact simulation states). This makes learning more accurate while still producing a policy that uses only the robot’s normal sensors.

- Domain randomization: In simulation, they keep changing things like friction, weight, and sensor noise—like practicing on many “virtual planets.” This helps the robot handle surprises in the real world.

- Reward regularization: They add safety-related penalties (like avoiding joint limits) so behaviors stay safe and realistic.

- Large-scale training: They use lots of simulated environments in parallel to train fast and robustly.

- Prompting at test time:

- Reward prompt: Turn your desired reward into a z (the “knob” vector) and run the policy.

- Goal pose prompt: Turn the target pose into a z and the robot moves to it.

- Motion tracking prompt: Turn each short segment of a motion clip into a series of z’s and the robot follows it.

- Few-shot adaptation: If zero-shot isn’t perfect in a new situation (like extra weight or different floor friction), they optimize the z’s for a few trials using simple, sampling-based search—no retraining the whole network.

Main results and why they matter

What it can do zero-shot on a real humanoid:

- Motion tracking: It can follow diverse motions (walking, dancing, sports-like moves). If it stumbles or gets off-balance, it naturally recovers and continues.

- Goal reaching: Given a sequence of target poses (even some that aren’t perfectly feasible), it moves toward them smoothly, making natural transitions without extra code.

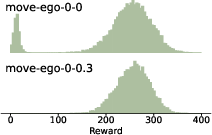

- Reward optimization: With simple reward prompts (e.g., “move backward while raising left arm”), it produces the desired behavior. You can also mix rewards—like mixing colors—to compose new behaviors (e.g., move backward + raise arms).

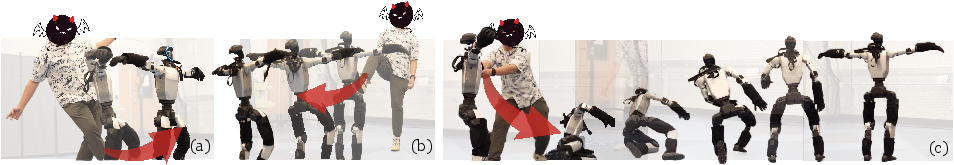

Robustness:

- Disturbance rejection: It withstands hard pushes and kicks, takes recovery steps, and even stands up after being pulled down—then returns to the desired behavior.

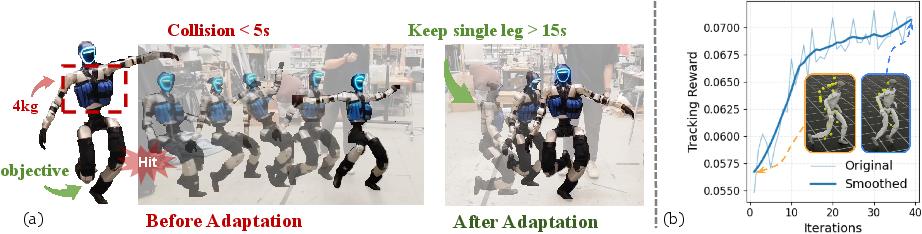

Few-shot adaptation:

- Single pose with payload: With a 4 kg torso weight added, the adapted prompt holds a one-leg stance much longer than zero-shot.

- Trajectory adaptation: For a jump-like motion on different friction, quick optimization reduces tracking error significantly. This shows fast, practical tuning without changing the trained networks.

Generalization:

- Works across different simulators (helps show robustness, not just tuned to one simulator).

- Handles out-of-distribution motions from new datasets, suggesting the learned skill space is broad.

Latent space structure:

- The “knob space” is smooth and meaningful: similar behaviors cluster together, and smoothly blending between two prompts produces natural, in-between motions. This is like sliding a cross-fade between two songs and hearing a sensible mix.

What this means for the future

BFM-Zero is a step toward robots you can direct with simple, flexible prompts, not custom code for each task. It shows:

- One general model can support many whole-body skills without retraining.

- Prompts can be goals, rewards, or motion clips—whatever is convenient.

- The robot can be robust and recover naturally in messy real-world situations.

- If needed, small amounts of extra interaction can quickly adapt it to new conditions.

Limitations and next steps:

- The variety and quality of learned behaviors still depend on the motion data used for training—bigger, better datasets likely mean better skills.

- Even though domain randomization helps, more powerful online adaptation will be useful for very complex tasks.

- Understanding how model size, data, and performance scale (so-called “scaling laws”) will guide building even more capable, general robot brains.

In short, BFM-Zero shows a promising path toward promptable, adaptable humanoids that can understand many kinds of instructions and handle the real world with grace.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.