Behavior Foundation Model for Humanoid Robots (2509.13780v1)

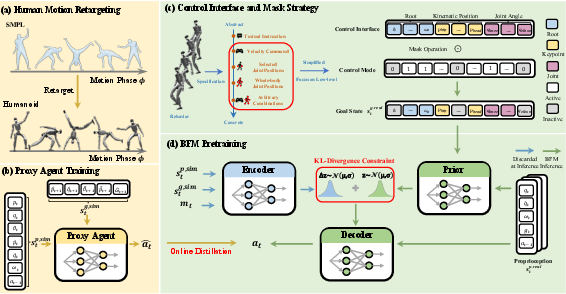

Abstract: Whole-body control (WBC) of humanoid robots has witnessed remarkable progress in skill versatility, enabling a wide range of applications such as locomotion, teleoperation, and motion tracking. Despite these achievements, existing WBC frameworks remain largely task-specific, relying heavily on labor-intensive reward engineering and demonstrating limited generalization across tasks and skills. These limitations hinder their response to arbitrary control modes and restrict their deployment in complex, real-world scenarios. To address these challenges, we revisit existing WBC systems and identify a shared objective across diverse tasks: the generation of appropriate behaviors that guide the robot toward desired goal states. Building on this insight, we propose the Behavior Foundation Model (BFM), a generative model pretrained on large-scale behavioral datasets to capture broad, reusable behavioral knowledge for humanoid robots. BFM integrates a masked online distillation framework with a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) to model behavioral distributions, thereby enabling flexible operation across diverse control modes and efficient acquisition of novel behaviors without retraining from scratch. Extensive experiments in both simulation and on a physical humanoid platform demonstrate that BFM generalizes robustly across diverse WBC tasks while rapidly adapting to new behaviors. These results establish BFM as a promising step toward a foundation model for general-purpose humanoid control.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching humanoid robots (robots shaped like people) to move their whole bodies in many different ways, using one general “brain” instead of lots of separate, task-specific ones. The authors call this general brain the Behavior Foundation Model (BFM). It learns a wide variety of movements (behaviors) from big motion datasets, and then can be steered to do different tasks—like following a motion clip, walking by following speed commands, or copying a person in VR—without retraining from scratch.

Goals and Questions

In simple terms, the paper asks:

- Can we build one model that understands “how to move like a human” and use it for many robot tasks, instead of building separate models for each task (like walking, tracking, or teleoperation)?

- Can this model handle different kinds of instructions (called control modes), like “walk forward at this speed,” “copy this motion clip,” or “follow my VR body pose,” all through a single, flexible interface?

- Can the model quickly learn new tricks (like a new acrobatic move) by reusing what it already knows, instead of starting over?

How They Did It (Methods)

Here’s the approach, explained with everyday ideas and analogies:

Step 1: Train a “proxy coach” in simulation (motion imitation)

- Think of a skilled coach who knows how to move like a human. The team first trains a strong “coach policy” in a simulator by making the robot imitate human motions from big datasets (like AMASS).

- To fit human motion to the robot’s body, they “retarget” it—like tailoring clothes to fit a different person. This makes sure the robot can try human-like moves safely and realistically in simulation.

Step 2: Pretrain the Behavior Foundation Model by learning from the coach (online distillation)

- Now they create a “student model” (the BFM) and let it practice in the simulator. As it acts, it asks the coach what the correct action should be and learns to match it.

- This setup (called DAgger and “online distillation”) is like a student driver practicing while a teacher corrects mistakes in real time.

Step 3: Use one flexible “control panel” for many tasks (masking)

- Different tasks give different instructions (control modes):

- Locomotion: “Move at this speed and turn like this.”

- Motion tracking: “Copy this full-body pose sequence.”

- VR teleoperation: “Follow the person’s hands and body in VR.”

- The authors design a single control panel (an input format) that can accept targets for the robot’s root (body position/rotation/velocities), key body points, and joint angles.

- A simple on/off mask (like checking boxes on a form) decides which parts of the control panel are active. This lets them switch or mix control modes without changing the model.

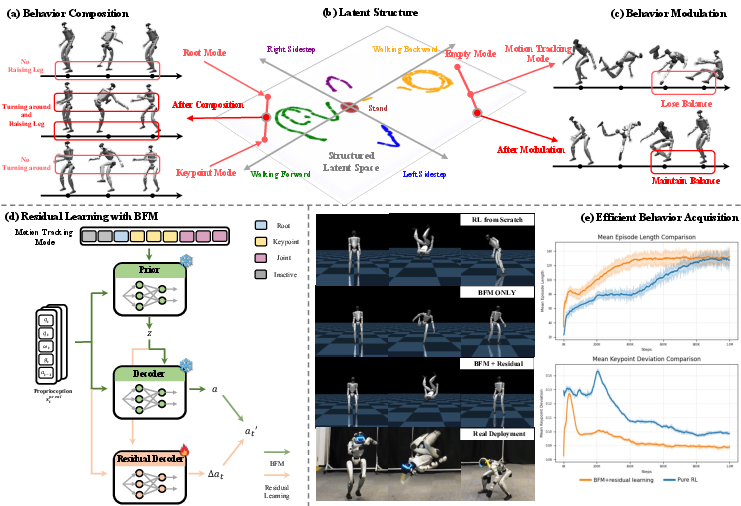

Step 4: Give the model a useful “imagination space” (a CVAE latent space)

- The BFM is built with a CVAE, a type of generative model. You can think of its “latent space” as secret coordinates that represent different styles of movement.

- This space turns out to be nicely organized: similar moves are close together; opposite moves are mirrored. That makes it possible to blend or tweak behaviors smoothly.

Step 5: Learn new tricks with small add-ons (residual learning)

- When the robot needs to learn a brand-new move (like a side salto), they keep the BFM frozen and only learn a small “residual” (a tiny correction layer).

- This is like adding a small booster to an already capable system, so training is much faster and safer than starting from zero.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

The authors tested their model in simulation and on a real Unitree G1 humanoid. Here’s what they found:

- One model, many tasks:

- The BFM can be steered to do locomotion (follow speed commands), full-body motion tracking (copy motion clips), and VR teleoperation (follow a human’s VR inputs), just by changing the mask on the same control panel.

- It often matches or beats dedicated “specialist” models and outperforms another general baseline (HOVER) across many tests.

- Zero-shot versatility:

- The BFM can perform some behaviors it wasn’t directly trained to do for that specific control mode (for example, using motion knowledge to help VR teleoperation), meaning it generalizes well.

- Behavior composition (mixing moves):

- By blending the latent codes from two modes (like “turning the body” and “lifting a leg”), the robot can perform a roundhouse kick—something neither mode alone did well. This shows the latent space is meaningful and supports creative combinations.

- Behavior modulation (tuning moves):

- By pushing the latent code slightly toward the desired mode (like turning a “dial”), the robot fixed a difficult landing in a butterfly kick. In general, a small push improved tracking accuracy; too big a push could hurt—so it’s a tunable tradeoff.

- Fast learning of new skills:

- With residual learning on top of the pretrained BFM, the robot learned challenging new behaviors (like a side salto) faster and more reliably than training a brand-new controller from scratch.

Why this is important:

- It shows a path toward “foundation models” for robot movement, similar to how foundation models work in language and images. Such models can cut down on time, cost, and effort when adding new robot abilities.

Implications and Potential Impact

- A single, general-purpose movement model could make humanoid robots more practical in the real world. Instead of building a new controller for every task, you can use one model and just change how you “ask” it to move.

- This flexibility can speed up development for applications like:

- Safe, responsive teleoperation (e.g., VR control)

- Motion tracking and performance (e.g., copying human demonstrations)

- Everyday mobility and recovery (e.g., standing up, balancing, walking over different terrains)

- The ability to quickly add new moves with small training tweaks (residuals) means robots can expand their skill sets rapidly, which is crucial for operating in messy, unpredictable environments.

- Overall, the paper is a step toward robust, “do-many-things” humanoid robots that learn from large motion libraries and adapt to new tasks without starting over every time.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper’s approach and evaluation:

- Arbitrary control modes are not truly supported in practice: the framework restricts control to low-level unions of root state, kinematic keypoints, and joint angles. How to extend BFM to higher-level modes (language, task graphs, semantic goals), exteroceptive goals (vision, audio), and haptic constraints remains open.

- Manual mask specification at deployment: masks are hand-crafted per task despite random mask training. Can the model infer or adapt control-mode masks online from partial commands, context, or user intent without manual configuration?

- Unmodeled goal-state distribution p(s_g|s_p): the paper defines it abstractly but does not learn or estimate it. Can we learn a goal prior/posterior or goal inference module to enable principled conditioning and automatic goal completion under partial or noisy specifications?

- Limited real-world quantification: sim-to-real is shown qualitatively; there are no real-robot metrics (tracking error, success rate, robustness, latency, energy, thermal behavior) across tasks. A standardized real-world benchmark suite is needed.

- Single hardware platform generalization: results are only on Unitree G1 (with wrists frozen). How well does BFM transfer across humanoid morphologies, different actuation (hydraulic, SEA), varied joint counts, and hand DOFs?

- No object interaction or manipulation: focus is on whole-body motion without contact-rich manipulation or loco-manipulation. Integrating hands, grasping, external contacts, tool use, and dual-arm coordination is a significant open direction.

- Terrain and environment diversity: evaluations lack uneven terrains, stairs, gaps, slopes, compliant/low-friction surfaces, and obstacle-rich scenarios. Robustness to diverse contact conditions and terrain geometry is untested.

- Safety and constraints: there is no safety filter (e.g., control barrier functions, model predictive safety layers) enforcing torque/velocity/joint limits, contact constraints, or collision avoidance. How to guarantee safety under arbitrary masks and goal specifications?

- Latency, delays, and sensor noise: the proprioceptive stack uses 25 past steps but does not explicitly model observation delay or communication jitter (e.g., VR). Methods for delay-compensated policies and robust state estimation are unexplored.

- Compute and real-time feasibility: inference latency, CPU/GPU requirements, and throughput on embedded hardware are not reported. What optimizations or model compression are needed for on-board, low-latency control?

- Sim-to-real gap analysis: domain randomization is used, but there is no systematic identification of dynamics mismatch, contact modeling errors, or ablation of randomization components. How effective is online system identification or adaptive residual dynamics modeling with BFM?

- Distillation stability and guarantees: DAgger-based online distillation lacks theoretical/empirical analysis of student performance bounds under mask-induced distribution shift. Under what conditions does the student match or surpass the teacher?

- CVAE design trade-offs: the decoder omits s_g to “force” latent structure, but this may harm conditional fidelity. Posterior collapse risk, KL-weight sensitivity, and calibration of output uncertainty (fixed variance) are not analyzed. Comparisons to diffusion, normalizing flows, or autoregressive policies are missing.

- Latent space interpretability and control: t-SNE visualizations are qualitative. Quantify disentanglement, linear separability, and controllability of latent factors; develop methods to discover and align latents with semantic axes (style, speed, symmetry).

- Generality of behavior composition: latent interpolation is shown on a single exemplar (roundhouse kick). Does interpolation reliably produce valid blends across diverse motion pairs, contact regimes, and timings? Define metrics and a compositionality test suite.

- Principled behavior modulation: classifier-free–style extrapolation uses a hand-tuned λ without stability guarantees. Can λ be adapted online (e.g., via performance gradients or value estimates), and what are safe ranges under different tasks?

- Residual learning scope and scalability: residuals are learned per new behavior with the base model frozen. How to manage many residuals (selection, composition, priority), avoid interference, and support continual skill growth without retraining?

- Catastrophic forgetting and multi-task interference: although BFM is frozen during residual learning, how to update the foundation model itself over time without degrading prior performance? Methods for conservative fine-tuning or modular adapters are needed.

- Data bias and filtering: hard negative mining plus dataset filtering may bias away from rare or challenging motions. Quantify coverage, diversity, and the effects of filtering on downstream generalization and robustness.

- Coverage beyond motion imitation: proxy training uses motion imitation; reward-free, task-agnostic exploration data and multi-task RL with sparse/learned rewards are not incorporated. Would broader data improve zero-shot transfer?

- Automatic goal completion and error correction: the system does not infer missing goals or repair inconsistent inputs. Develop mechanisms for goal completion, constraint satisfaction, and conflict resolution when control inputs are partial or contradictory.

- Long-horizon planning and hierarchy: no hierarchical interface connects BFM to planners that reason over sequences of behaviors, task constraints, or environment goals. How to integrate high-level planners with low-level BFM latents?

- Recovery behaviors and robustness: there is no explicit evaluation of fall recovery, disturbance rejection beyond small pushes, or failure detection and mitigation protocols on hardware.

- Evaluation metrics breadth: tracking errors dominate; energy efficiency, peak torques, contact quality (slip, CoP margins), footstep timing accuracy, and human-perceived naturalness are not reported. Add multi-faceted metrics to capture safety and efficiency.

- Mask sampling policy: Bernoulli(0.5) and a brief curriculum are ad hoc. Can we learn a distribution over masks that reflects real usage, encourages coverage of rare modes, or enforces semantic validity (e.g., coherent subsets of controls)?

- Goal-conditioned uncertainty and risk: the model’s uncertainty is not estimated or exploited. How to calibrate uncertainty, detect out-of-distribution goals, and perform risk-aware control (e.g., via ensembles or probabilistic decoders)?

- Dynamics and contact priors: foot contact schedules and phase structure are implicit. Would explicit contact/phase representations, hybrid models, or physics-informed priors improve stability and compositional control?

- Benchmarking against modern generative policies: no head-to-head comparisons with diffusion policies or hybrid diffusion–policy distillation approaches on the same tasks/datasets. Such baselines could clarify modeling choices.

- Training efficiency and scaling laws: training time, compute budget, and sample complexity are not disclosed. How do performance and generalization scale with data volume, environment count, and model size?

- Automatic curriculum design: early termination and basic curricula are used, but task/skill curricula are hand-tuned. Learning curricula (goal difficulty, mask sparsity, perturbation magnitude) may accelerate and stabilize pretraining.

- Safety and ethics in human-in-the-loop teleoperation: latency, intent ambiguity, and physical interaction risks are not analyzed. Introduce safety constraints, shared autonomy, and fail-safes for teleop scenarios.

- Reproducibility and assets: details on code availability, trained weights, and retargeting tools are not provided. Public release is needed for independent verification and extension.

Glossary

- AMASS dataset: A large human motion capture dataset aggregating many MoCap sources into a unified SMPL-parameterized format. "We select the publicly available AMASS dataset~\cite{mahmood2019amass} where each motion sample is parameterized by the SMPL model~\cite{loper2023smpl}."

- Behavior Foundation Model (BFM): A generative model pretrained on large-scale behavioral data to encode reusable knowledge for humanoid control. "To this end, we introduce the Behavior Foundation Model (BFM) for humanoid robots, a generative model pretrained on large-scale behavioral datasets to capture broad and reusable behavioral knowledge."

- Bernoulli distribution: A discrete probability distribution over binary outcomes; used here to randomly activate elements of a control mask. "we directly sample each element of the mask from a Bernoulli distribution , facilitating application of arbitrary control modes."

- Classifier-free Guidance: A technique from diffusion models that combines conditional and unconditional predictions to steer generation strength. "We propose to obtain latent variables in a similar way to Classifier-free Guidance~\cite{ho2022classifier} in Diffusion models:"

- Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE): A VAE variant that conditions both encoder and decoder on side information to model conditional distributions. "We adopt a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) to model the log-probability ."

- Curriculum learning: A training strategy that gradually increases task difficulty or constraints to stabilize and accelerate learning. "We employ curriculum learning to the regularization and penalty terms, encouraging the policy to focus on motion imitation initially and gradually leverage penalty and regularization to shape the behaviors."

- DAgger framework: Dataset Aggregation; an online imitation learning algorithm that iteratively collects data under the learner’s policy with expert labels. "we employ the DAgger framework~\cite{ross2011reduction} to optimize the objective of BFM's pretraining."

- Domain randomization: A robustness technique that randomizes simulator parameters (e.g., dynamics, perturbations) to improve sim-to-real transfer. "We also apply domain randomization during training by randomizing dynamics and applying external perturbations."

- Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO): The variational objective optimized by VAEs, balancing reconstruction and KL divergence terms. "The Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) of CVAE is expressed as:"

- Goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (RL): An RL setting where the policy is conditioned on a desired goal state to guide behavior. "We formulate the problem of humanoid control as a goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (RL) task, where a policy is trained to achieve certain objectives."

- Hard negative mining: A sampling strategy that prioritizes difficult examples the model currently fails on to improve coverage and performance. "To address this issue, we employ the strategy of hard negative mining by periodically evaluating our policy over the entire dataset and dynamically adjusting the sampling probability for each motion sample."

- HOVER: A unified masked-control policy for humanoid WBC tasks that supports multi-modal control. "HOVER~\cite{he2025hover} attempts to address this by employing a unified policy with a masking strategy to achieve multi-modal control, demonstrating versatile humanoid control across diverse WBC tasks."

- Inverse kinematics (IK): A method to compute joint configurations that achieve desired end-effector poses. "Besides processing VR signals with IK, other teleoperation systems~\cite{he2024omnih2o} directly map kinematic data from VR controllers to the humanoid, enabling highly expressive and accurate whole-body control."

- IsaacGym: A high-performance GPU-based physics simulation platform for large-scale parallel RL. "The training of our proxy agent and BFM is conducted in IsaacGym~\cite{makoviychuk2021isaac}, with 8192 parallel environments."

- Jensen Inequality: A mathematical inequality used here to derive a tractable lower bound on a log-expectation. "By applying the Jensen Inequality, we may obtain a tractable lower bound as a surrogate of the original objective:"

- KL-Divergence (Kullback–Leibler divergence): A measure of dissimilarity between two probability distributions, used for regularizing latent spaces. "and is the KL-Divergence operator"

- Loco-manipulation: Tasks involving simultaneous locomotion and manipulation with whole-body coordination. "A more concrete and widely adopted control mode, especially for locomotion and loco-manipulation, involves the velocity commands and base height commonly combined with other signals like gait and posture~\cite{xue2025unified}"

- Masked online distillation: A learning setup where a student policy is trained online to match a teacher under randomly masked conditioning modes. "BFM integrates a masked online distillation framework with a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE)"

- Mean per-joint error (MPJPE): A metric measuring average joint-angle or joint-position error between predicted and reference motions. "we adopt the same metric set for these two tasks comprised of the mean per-keypoint error (MPKPE) , mean per-joint error (MPJPE) "

- Mean per-keypoint error (MPKPE): A metric measuring average 3D keypoint position error across body landmarks. "we adopt the same metric set for these two tasks comprised of the mean per-keypoint error (MPKPE) , mean per-joint error (MPJPE) "

- Motion imitation: Training a policy to reproduce reference motions by tracking pose, velocity, and other motion features. "we train a proxy agent denoted as using motion imitation."

- Mujoco: A physics engine commonly used for robotics simulation and control research. "and demonstrate both the sim-to-sim results in Mujoco~\cite{todorov2012mujoco} and sim-to-real results in real world."

- PD controller: Proportional-Derivative controller; converts target joint positions into torques/commands for actuation. "The action represents the target joint positions for humanoids, which are then fed into the PD controller to actuate the robot's degrees of freedom."

- Proprioception: Internal sensing of the robot’s own state (e.g., joint positions, velocities, inertial measurements). "The state comprises both the humanoid's proprioception and the goal state ."

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): A popular on-policy RL algorithm optimizing a clipped surrogate objective for stable training. "Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm~\cite{schulman2017proximal} is employed to maximize the cumulative reward ."

- Reference State Initialization (RSI): A technique that initializes episodes from random points in reference motions to stabilize imitation learning. "We employ the Reference State Initialization (RSI) framework~\cite{peng2018deepmimic}, where the starting point of the reference motion is randomly sampled and the robot's initial state is derived from the corresponding reference pose."

- Residual learning: Learning an additive correction on top of an existing model’s output to refine behavior or adapt to new tasks. "we integrate residual learning~\cite{he2016deep} into our framework, enabling efficient acquisition of novel behaviors"

- Retargeting: Adapting human motion data to a robot’s morphology via optimization or mapping. "we employ a two-stage retargeting approach~\cite{he2024learning}."

- Roll–Pitch–Yaw (RPY): A parameterization of 3D orientation using sequential rotations about the x, y, and z axes. "Root Control: target root translation, orientation (specified by RPY), linear velocity and angular velocity;"

- Sim-to-real: The transfer of policies learned in simulation to physical robots operating in the real world. "and demonstrate both the sim-to-sim results in Mujoco~\cite{todorov2012mujoco} and sim-to-real results in real world."

- SMPL model: A parametric 3D human body model that represents pose and shape for animation and motion datasets. "each motion sample is parameterized by the SMPL model~\cite{loper2023smpl}."

- t-SNE: A non-linear dimensionality reduction method for visualizing high-dimensional data in 2D or 3D. "we apply the t-SNE algorithm~\cite{maaten2008visualizing} to project the high-dimensional latent variables into a 2D plane for visualization."

- Teleoperation: Controlling a robot remotely by mapping human inputs (e.g., VR) to robot motions. "other teleoperation systems~\cite{he2024omnih2o} directly map kinematic data from VR controllers to the humanoid, enabling highly expressive and accurate whole-body control."

- Unitree G1: A specific 29-DoF humanoid robot platform used for real-world experiments. "We adopt the Unitree G1 humanoid robot~\cite{unitreeg1} as an agile and powerful platform for real-world deployment, which stands 1.3 meters tall and has 29 degrees of freedom."

- Whole-body control (WBC): Control approaches that coordinate all joints and limbs to achieve complex full-body tasks. "Whole-body control (WBC) of humanoid robots has witnessed remarkable progress in skill versatility, enabling a wide range of applications such as locomotion, teleoperation, and motion tracking."

- Zero-shot: Performing new tasks or behaviors without task-specific training or fine-tuning. "Behavior Foundation Model enables humanoid robots to perform a variety of behaviors in a zero-shot manner, including (1) a swimming pose, (2) sitting down on the ground, (3) standing up from the ground, and (4) butterfly kick."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.