RelayLLM: Efficient Reasoning via Collaborative Decoding

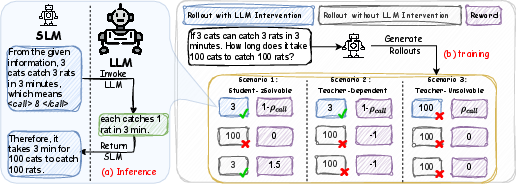

Abstract: LLMs for complex reasoning is often hindered by high computational costs and latency, while resource-efficient Small LLMs (SLMs) typically lack the necessary reasoning capacity. Existing collaborative approaches, such as cascading or routing, operate at a coarse granularity by offloading entire queries to LLMs, resulting in significant computational waste when the SLM is capable of handling the majority of reasoning steps. To address this, we propose RelayLLM, a novel framework for efficient reasoning via token-level collaborative decoding. Unlike routers, RelayLLM empowers the SLM to act as an active controller that dynamically invokes the LLM only for critical tokens via a special command, effectively "relaying" the generation process. We introduce a two-stage training framework, including warm-up and Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) to teach the model to balance independence with strategic help-seeking. Empirical results across six benchmarks demonstrate that RelayLLM achieves an average accuracy of 49.52%, effectively bridging the performance gap between the two models. Notably, this is achieved by invoking the LLM for only 1.07% of the total generated tokens, offering a 98.2% cost reduction compared to performance-matched random routers.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces RelayLLM, a way for a small, fast AI (a Small LLM, or SLM) to “team up” with a bigger, smarter AI (a LLM, or LLM) only when it really needs help. Instead of sending the whole problem to the big AI, the small AI writes most of the answer itself and briefly “calls” the big AI for a few words at the hardest moments—like passing a baton in a relay race. This makes the system faster and much cheaper, while keeping accuracy high.

What questions do the researchers ask?

In simple terms, they ask:

- Can a small AI learn to solve tough problems while asking a big AI for help only at critical moments?

- Can it decide, on its own, exactly when to ask for help and how much help to ask for?

- Will this collaboration boost accuracy a lot while using the big AI very little?

How does their method work?

The basic idea (taking turns like a relay)

- The small AI starts writing the answer one short piece at a time (think: words or small chunks called “tokens”).

- When it feels stuck, it writes a special command, like “<call>n</call>”, which means: “Big AI, please write the next n tokens for me.”

- The big AI writes those n tokens, then hands control back to the small AI, which continues from there.

- This back-and-forth can happen multiple times, but only when needed.

This is called “token-level collaborative decoding,” which just means the two AIs take turns writing small parts of the answer, not the whole thing at once.

Training in two steps (learning the skill, then the strategy)

- Warm-up (learning the “call” command): The small AI is first taught the mechanics—how to produce and understand the special call tokens properly. This is like learning how to press the “help” button and how the handoff works.

- Reinforcement learning (learning when to ask): Next, the small AI practices many times, gets feedback (rewards or penalties), and learns a strategy: be independent when possible, ask for help only when it matters, and don’t waste help.

To make sure training focuses on useful cases, they keep questions where the big AI can actually help (so calling for help isn’t pointless).

Rewards for smart help-seeking

The training uses a reward system to encourage good habits:

- If the small AI can solve a problem by itself, it gets extra points for independence.

- If a problem is only solved when the big AI helps, the model is encouraged to call for help rather than guess.

- If a problem is too hard for both, trying to ask for help still earns a small reward (so the model learns to seek help when very uncertain).

Overall, the small AI learns a simple rule of thumb:

- Solve it yourself when you can.

- Ask for help when you can’t.

- Don’t overspend on help.

What did they find?

Here are the main results, explained plainly:

- Big accuracy boost with tiny help: Across six math benchmarks, the method lifts average accuracy from about 42.5% to 49.5%, while the big AI writes only about 1% of the total tokens. That’s a huge gain for very little extra cost.

- Much cheaper than common alternatives: Compared to a system that sends entire hard questions to the big AI, RelayLLM reduces the “big AI usage” by about 98% to get similar performance.

- Better than other token-level methods: RelayLLM beats a strong baseline that needs an extra controller network, but does so with less overhead.

- Learns useful habits: After training, the small AI also performs better even when the big AI is turned off on easier tasks—meaning it picked up better reasoning patterns during collaboration.

- Works beyond math: Even on general knowledge tests it wasn’t trained on, the small AI still improves by smartly calling the big AI when needed.

- “Just enough” help is best: Letting the small AI decide how many tokens to request works better (and cheaper) than always asking for a fixed amount.

Why does this matter?

This work shows a practical way to make AI assistants both smart and efficient:

- Faster and cheaper: Most of the work is done by the small, fast model; the big model is used only sparingly.

- Scalable and greener: Lower compute use means less energy and lower costs—useful for schools, startups, and running AI on devices with limited power.

- Better user experience: Systems can stay responsive while still solving tricky problems well.

- Broad applications: From math tutoring to coding help and everyday assistants, many tools can get “expert-level” boosts without paying expert-level costs for every step.

In short, RelayLLM teaches small AIs to be confident and careful: do what you can yourself, and ask for just the right amount of help exactly when you need it. This simple idea leads to strong accuracy gains with minimal extra cost, making powerful AI more accessible and efficient.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of unresolved issues that future work could address:

- External validity across model families: All experiments use Qwen3-based SLMs and an 8B Qwen3 teacher; it remains unknown how well RelayLLM transfers to heterogeneous teachers (different architectures, vocabularies, tokenizers), or to closed-source APIs with different tokenization and decoding defaults.

- Tokenization and command compatibility: The method depends on SLM-emitted special tokens (<call>n</call>) and strips them before teacher input. It is unclear how robust this is when teacher and student have different tokenizers, or if the teacher’s tokenizer splits or normalizes the surrounding context in ways that affect collaboration.

- Multilingual and multimodal generalization: Training and most evaluations are math-centric and English-centric; it is unknown whether token-level relaying works for multilingual, cross-lingual, or multimodal tasks (vision, speech), especially where verifiers are weaker or unavailable.

- Reliance on verifiable rewards: GRPO training uses RLVR with rule-based correctness (math answer parsing). How to extend RelayLLM to open-ended tasks without deterministic verifiers (e.g., safety, reasoning over narratives) remains unclear.

- Judge reliability in evaluation: Several benchmarks use GPT-4o-mini as a semantic judge. The sensitivity of results to judge choice, judge prompt, adversarial formatting, and judge error rates is not analyzed.

- Cost metrics beyond call ratio: The paper reports token call ratios but not wall-clock latency, end-to-end throughput, GPU utilization, or energy consumption under realistic serving (e.g., network/API overhead, KV-cache misses across intermittent calls).

- Training-time compute and cost: Collaborative RL training involves sampling groups, invoking teachers, and filtering data; the paper does not quantify training-time cost, wall-clock time, or carbon footprint relative to baselines.

- Data filtering bias: Filtering to queries with ≥50% teacher pass rate removes “teacher-failed” data. This may bias the learned policy and inflate reported gains; sensitivity to the threshold, group size, and filtering strategy is unreported.

- Robustness when the teacher is wrong: There is no mechanism to detect or mitigate erroneous teacher continuations (e.g., verifier-in-the-loop or arbitration). The impact of teacher hallucinations on the SLM’s subsequent reasoning is unexplored.

- No rollback/correction strategy: If a teacher intervention degrades the trajectory, the SLM lacks a way to reject or roll back those tokens; policies for post-intervention verification or selective acceptance are not studied.

- Safety and prompting risks: The security implications of exposing a callable “<call>” protocol are unaddressed (e.g., user-injected <call> tokens to force expensive interventions, prompt injection that manipulates delegation behavior, or denial-of-wallet attacks).

- Multi-teacher routing: RelayLLM considers a single teacher. How to extend to multiple teachers (e.g., domain experts) with token-level selection, cost-aware choice, and online specialization is open.

- Adaptation to dynamic teacher availability/cost: The reward penalizes call ratio uniformly. How to adapt policies to variable teacher latency, pricing, or rate limits in production is not explored.

- Interaction with chain-of-thought (“thinking”) modes: Models are run in non-thinking mode; it is unknown whether token-level relays over explicit thoughts change calling patterns, improve performance, or shift cost-efficiency.

- Long-context and multi-turn settings: The impact of relaying on long-context reasoning, multi-turn dialogues, and context compounding (call tokens + teacher tokens increasing prompt length) is not evaluated.

- Delegation length prediction: The SLM chooses n, but there is no mechanism to early-stop teacher generation when sufficient guidance is obtained, nor to dynamically extend if needed. Policies for adaptive termination/extension are not investigated.

- Where and why calls occur: There is no analysis of the token positions or reasoning phases where calls are triggered, nor whether the model reliably identifies “critical tokens” across tasks and inputs.

- Stability and variance: Results lack reporting of variance across random seeds, group sizes, and RL hyperparameters, making training stability and reproducibility uncertain.

- Baseline coverage: Comparisons omit several strong recent approaches (e.g., speculative reasoning variants, judge-decoding, advanced thought-level collaboration). A broader empirical comparison would clarify the relative contribution of token-level relaying.

- Distillation to reduce dependence: Although teacher-free evaluations show some gains, the paper does not explore explicit distillation (from collaborative traces) to further reduce or eliminate reliance on the teacher at inference.

- Handling “teacher-unsolvable” queries: The exploration reward encourages calling even when teachers fail, which may waste cost. Strategies to identify hopeless cases early and avoid futile calls are not developed.

- Generalization under distribution shift: Cross-LLM experiments show sensitivity to teacher mismatch. How to regularize training for robustness to teacher changes (or to benefit from stronger teachers at inference) remains open.

- Fairness and multilingual safety: No assessment of demographic, linguistic, or domain biases in calling behavior (e.g., over-calling on specific languages or topics), nor analyses of disparate cost/quality impacts.

- Implementation and serving practicality: Frequent token-level switching may be awkward for standard serving stacks (e.g., cache fragmentation, batching interference). Systems-level techniques to preserve throughput under relaying are not provided.

- Failure case taxonomy: The work lacks qualitative analyses of failure modes (e.g., over-calling on easy items, under-calling on edge cases, compounding errors after bad calls), which could inform targeted training interventions.

- Licensing and provenance risks: Teacher tokens are injected into SLM contexts; potential style leakage, licensing implications, or IP constraints around mixing outputs are not discussed.

- Hyperparameter sensitivity of rewards: The difficulty-aware reward uses fixed constants (e.g., 1.5 bonus, −1 penalty). The sensitivity of performance/cost trade-offs to these values and principled ways to tune them remain unstudied.

- Extension beyond text: It is unknown whether token-level relays transfer to program synthesis (execution as a teacher), retrieval-augmented generation (retrievers as teachers), or tool-augmented agents with non-text outputs.

Glossary

- Ablation study: A controlled analysis where components are systematically removed or altered to assess their impact on performance. "we conducted an ablation study using the Qwen3-1.7B model in Table~\ref{tab:ablation}."

- Advantage (RL): The relative performance signal used in policy gradient methods to indicate how much better a sampled outcome is compared to a baseline or average. "The advantage is derived from the group-normalized rewards defined below:"

- avg@32: An evaluation metric that averages accuracy over 32 sampled outputs to provide a robust measure on difficult benchmarks. "For the high-difficulty AIME datasets, we report the avg@32 metric to ensure a robust evaluation."

- Autoregressive generation: A decoding process where each token is generated conditioned on previously generated tokens. "By default, generates tokens autoregressively based on the current context history as a normal LLM."

- bad_words: A decoding constraint that forbids specific tokens from being generated during inference. "implemented via bad_words=[

<call>'',</call>''] when inference" - Call ratio: The fraction of tokens in a response that are generated by the large (teacher) model, used to measure collaboration cost. "The x-axis represents the Call Ratio (percentage of tokens generated by the teacher model), and the y-axis denotes the average accuracy."

- Calling command token: A special token emitted by the small model to pause its own generation and request the large model’s intervention. "when the model generates the calling command token, generation halts, and the system invokes the teacher model via the API."

- Cascading: A collaboration strategy that routes entire queries to a large model when they are deemed difficult. "Existing approaches to different-sized model collaboration often rely on

cascading'' orrouting'' mechanisms" - CITER: A token-level routing baseline that uses an external controller to decide when to switch models. "We also add CITER~\citep{zheng2025citer}, a token-level routing method as the baseline method which requires an additional controller."

- Collaborative decoding: Joint generation where multiple models interleave their outputs to produce a final response. "we propose RelayLLM, a novel framework for efficient reasoning via token-level collaborative decoding~\citep{shen2024learning} without an additional controller."

- Competence boundary: The subset of tasks where a model (e.g., the teacher) is capable enough to provide useful intervention. "This step ensures that the training data lies in the competence boundary of the large model and the responses can contribute effectively."

- Cross-entropy loss: A standard supervised learning objective measuring the discrepancy between predicted and target token distributions. "We fine-tune on this constructed dataset using standard cross-entropy loss."

- Data distribution shift: A mismatch between training and inference data distributions that can degrade performance. "This data construction strategy ensures effective on-policy training data to prevent data distribution shift of the small model, while simulating various calling scenarios."

- Delegation length: The number of tokens requested from the large model during an intervention. "we explicitly simulate varying degrees of reliance on the expert model by synthesizing delegation lengths across multiple orders of magnitude."

- Difficulty-Aware Reward: A reinforcement learning signal that adapts rewards based on whether a query is solvable independently, teacher-dependent, or unsolvable. "the Difficulty-Aware-Reward mechanism outperforms the Simple-Reward in performance, with a marginal increase in token consumption."

- End-of-sequence (EOS) token: A special token indicating the end of generation. "or stops early if an end-of-sequence ``[EOS]'' token is reached"

- Greedy decoding: A decoding strategy that selects the highest-probability token at each step without sampling. "we report standard accuracy (pass@1) using greedy decoding."

- Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO): An RL algorithm that optimizes a policy by comparing sampled outputs against a group average. "We leverage Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO)~\citep{shao2024deepseekmath} to refine the policy of "

- Indicator function: A function that returns 1 for true conditions and 0 otherwise, often used in reward definitions. "where is the indicator function, thus the responses are scored by their correctness and penalized by the cost of calling the expert model."

- Interleaved generation: A decoding process where control alternates between models, inserting segments of output from each. "we introduce an interleaved generation process where the small model generates a special command token () to pause its own generation and invoke the large model for a specified number of tokens."

- Kullback–Leibler divergence (D_KL): A measure of divergence between probability distributions used as a regularizer in RL training. "where $\mathbb{D}_{\mathrm{KL} = D_{\mathrm{KL}(\pi_{\theta} \parallel \pi_{\mathrm{ref})$ is the regularization term."

- LLM: A high-capacity neural LLM capable of complex reasoning, typically expensive to run. "LLMs have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in complex reasoning and problem-solving"

- Logits-level ensembling: Combining model outputs at the pre-softmax (logit) level to improve performance. "ranges from weight-level merging~\citep{wortsman2022model, huang2023lorahub} and logits-level ensembling~\citep{liu2024tuning,li2023contrastive} to text-level interaction."

- Multilayer perceptron (MLP): A feedforward neural network used here as an external scoring module in a baseline. "CITER relies on an external MLP to estimate a score every token, which introduces substantial latency and computational overhead."

- Non-thinking mode: An inference configuration where models generate directly without explicit chain-of-thought reasoning traces. "we consistently run the models in non-thinking mode."

- On-policy training data: Training samples generated from the current model’s own distribution, reducing mismatch with inference. "This data construction strategy ensures effective on-policy training data to prevent data distribution shift of the small model"

- pass@1: Accuracy measured by whether the top (single) generated answer is correct. "we report standard accuracy (pass@1) using greedy decoding."

- Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Reward (RLVR): An RL paradigm where rewards are deterministically validated by a verifier. "by adopting the Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Reward (RLVR) paradigm~\citep{Lambert2024TLU3P}."

- Rollouts: Sampled trajectories or outputs used for evaluating and updating a policy. "During GRPO training, we sample a group of rollouts (both with and without LLM intervention) and classify the query difficulty..."

- Router: A component that decides which model should handle a query based on estimated difficulty. "Unlike routers, RelayLLM empowers the small model to act as both a problem solver and an active controller that dynamically requests assistance only when necessary."

- Routing: The process of directing queries or tokens to different models based on difficulty or policy. "Existing approaches to different-sized model collaboration often rely on

cascading'' orrouting'' mechanisms" - Semantic judge: An automatic evaluator that checks whether a generated answer semantically matches the ground truth. "We use GPT-4o-mini as a semantic judge to verify the model's output against the ground truth"

- Stop sequence: A decoding parameter that halts generation when a specified token pattern appears. "We implement the switching mechanism as a stop sequence in the sampling parameters"

- String concatenation: The operation of joining strings end-to-end, used to define command patterns. "where denotes string concatenation, and represents the number of tokens required from the larger LLM."

- Surrogate objective: An optimization target used in policy gradient methods that approximates the true objective with clipping for stability. "The surrogate objective is computed as "

- Token-level collaborative decoding: Fine-grained collaboration where models interleave at the token level rather than entire queries. "we propose RelayLLM, a novel framework for efficient reasoning via token-level collaborative decoding."

- Token-level routing: Deciding at each token whether to delegate generation to another model. "CITER~\citep{zheng2025citer}, a token-level routing method"

- Tokenizer: The component that converts text into tokens; consistency across models improves collaboration. "the generation style, token distribution, vocabulary and tokenizer are more consistent, making collaboration more stable."

- Tool-use agents: Models that issue special commands to invoke external tools or systems during reasoning. "Inspired by tool-use agents~\citep{wolflein2025llm, zheng2025parallel}"

- vLLM inference engine: A high-throughput serving system for LLMs that enables efficient interaction during collaborative decoding. "we serve the teacher model via the vLLM inference engine~\citep{kwon2023efficient}."

- Warm-up (supervised): An initialization phase where the model learns to emit valid control commands before RL training. "We first employ a supervised warm-up phase to teach the model the syntactic structure of calling commands."

- Teacher-free setting: An evaluation mode where the model is prevented from invoking the teacher to assess intrinsic reasoning. "Surprisingly, evaluations in a teacher-free setting reveal that the model internalizes effective reasoning patterns during collaboration"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete, deployable use cases that leverage RelayLLM’s token-level collaborative decoding, the <call>n</call> command interface, and GRPO-based help-seeking policy to reduce latency and cost while maintaining accuracy.

- Cost-optimized hybrid inference for production assistants

- Sectors: software, customer support, e-commerce, finance, education

- What: Deploy a small on-device or lightweight server model as the primary responder that dynamically “bursts” to a larger model only for critical tokens (∼1% call ratio observed), preserving quality with a fraction of the cost.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Relay middleware in the serving stack (e.g., vLLM/Inference Server plugin) that intercepts <call>n</call>, forwards context to a teacher model, merges tokens back, and logs call ratio for FinOps.

- Budget caps and per-tenant policies that enforce max token spend while maintaining SLA.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Network reliability for round-trips; teacher model availability; alignment between student and teacher tokenizers (family consistency helps); monitoring for distribution shifts if the teacher changes.

- Edge–cloud assistants with privacy-preserving “burst” help

- Sectors: mobile/IoT, healthcare (non-diagnostic), enterprise productivity

- What: On-device SLM handles most reasoning locally and calls the cloud LLM only when necessary, minimizing data exposure and cost.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Mobile SDK implementing the <call>n</call> protocol with local caching and encrypted, minimal-context relays.

- “Teacher-free” fallback mode using the trained SLM alone when offline (benefits from observed intrinsic gains).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Privacy reviews to ensure that the tokens forwarded do not include sensitive fields unless safely handled; secure channels/enclaves for relayed segments; clear data retention policies.

- Developer coding copilots with token-level escalation

- Sectors: software engineering, DevOps

- What: Local SLM provides inline suggestions; on ambiguous or complex code regions, it requests a small LLM continuation to improve correctness without fully offloading.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- IDE extensions integrating relay decoding; per-file or per-organization call-ratio quotas; token-level telemetry for value/cost attribution.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Verifiers for code tasks (tests, linters) improve RL training; careful handling of proprietary code when relaying.

- Tutoring and math/logic problem solvers with verifiable rewards

- Sectors: education

- What: Use RLVR with deterministic verifiers (e.g., math answer checkers) to train SLMs that know when to ask for help, enabling affordable step-by-step tutoring on low-end devices.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- RelayLLM training recipe: supervised warm-up to learn commands + GRPO with difficulty-aware reward; teacher served via inference engine; dataset filtering to remain in teacher competence region.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of reliable verifiers (answer checkers, unit tests); maintaining a stable teacher model during deployment.

- Contact-center triage and knowledge retrieval assistants

- Sectors: customer support, enterprise knowledge management

- What: Fast SLM handles FAQs and routine steps; triggers brief expert tokens for tricky policy exceptions or compositional queries, cutting latency and GPU minutes.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Relay-aware retrieval-augmented generation (RAG): SLM handles retrieval and framing; teacher is invoked only for synthesis-critical spans.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Latency budget for back-and-forth turns; domain-specific verifiers (where possible) to sustain RLVR improvements.

- Moderation and review queues with selective escalation

- Sectors: trust & safety, legal/compliance

- What: SLM resolves clear-cut cases; invokes LLM for ambiguous content or edge cases to raise accuracy at low incremental cost.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Policy-aware routing that factors call ratio into triage budgets; per-category thresholds to avoid overuse.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear thresholds and audit logs; human-in-the-loop for unresolved items.

- FinOps and observability for AI cost governance

- Sectors: platform engineering, finance (internal cost control)

- What: Track and optimize call ratios, token spend, and accuracy uplift; A/B test budgets versus outcomes.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Dashboards exposing per-request call ratios, accuracy deltas, and teacher-size trade-offs; guardrails to prevent regression when swapping teachers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate logging/tracing at token granularity; stable evaluation harnesses.

- Research and teaching: token-level collaboration baselines

- Sectors: academia, labs

- What: Use RelayLLM as a reproducible baseline for token-level collaboration on verifiable tasks (math/code), including public datasets (e.g., DAPO) and open models (Qwen family).

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Training templates with data filtering, GRPO hyperparameters, and reward configurations; cross-teacher evaluation protocols.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Compute for group sampling in GRPO; open-weight teachers with permissive licenses.

- Accessibility and writing assistance on-device

- Sectors: consumer apps

- What: SLM drafts text, emails, or summaries locally; escalates short spans to a cloud LLM for complex phrasing, citations, or reasoning-heavy passages.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Keyboard or OS-level assistant with adjustable cost slider and offline-first behavior.

- Assumptions/dependencies: UX for user consent on when to relay; caching to avoid repeated calls for the same context.

Long-Term Applications

The following opportunities require further research, scaling, or ecosystem development—often extending beyond verifiable tasks and into multimodal, safety-critical, or standardized deployments.

- General-purpose token-level tool orchestration (beyond LLM-as-teacher)

- Sectors: software, robotics, data science

- What: Generalize <call> to invoke external tools (solver, SQL engine, code runner, planner) for just-in-time micro-interventions at the token level.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- “Token-level Tool Router” SDK; integration with function-calling and structured tool outputs; mixed-initiative planning in the decoder loop.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Tool response alignment to language tokens; latency hiding; robust semantics for concatenating tool outputs into context.

- Multimodal relay decoding for perception–reasoning workloads

- Sectors: autonomous systems, healthcare imaging, manufacturing quality control

- What: Vision/audio SLMs request short bursts of multimodal expert tokens for complex perception or cross-modal reasoning.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Unified relay interface across text/vision/audio; streaming co-decoding with bounded budgets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multimodal tokenization compatibility; reliable verifiers or proxy rewards; real-time deadlines.

- Safety-critical decision support with provable guardrails

- Sectors: healthcare (clinical decision support), finance (risk/compliance), aviation/industrial control

- What: Combine token-level escalation with formal verification, calibrated uncertainty, and human oversight to meet regulatory standards.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Verifier-driven RL for domain rules; audit trails recording every relay event; call-ratio caps for predictable compute; red-teaming of the help-seeking policy.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Certified verifiers; regulatory acceptance of hybrid inference; thorough reliability and bias evaluations.

- Standardization of relay protocols and interoperability

- Sectors: cloud platforms, MLOps vendors, model providers

- What: Open standards for command tokens, pause/resume APIs, and context redaction so any SLM can collaborate with any teacher model or tool.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Relay Decoding API spec; reference implementations for major serving stacks; conformance tests.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cross-vendor cooperation; governance for privacy and telemetry; handling tokenizer mismatches.

- Dynamic teacher selection and market-based routing

- Sectors: cloud marketplaces, enterprise platforms

- What: Select the teacher per request based on price–latency–quality—possibly switching mid-generation—while mitigating distribution shift.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Teacher portfolios with performance profiles; online learning to adapt to teacher drift; SLAs expressed in maximum call ratios and quality targets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robustness to teacher swaps (paper shows sensitivity); metadata standardization; real-time cost signals.

- Knowledge transfer and gradual teacher offloading

- Sectors: education tech, enterprise AI

- What: Use relay training to incrementally reduce teacher reliance (teacher-free mode), approaching full on-device operation over time.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Scheduled “dieting” curricula that cap call ratios and encourage independence; periodic distillation from relay traces.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable self-evaluation or verifiers; careful balance to avoid accuracy collapse on hard tasks.

- Federated and privacy-first deployments with minimal data egress

- Sectors: healthcare, public sector, edge IoT

- What: Combine on-device SLMs, secure enclaves, and selective token relays to comply with strict data localization and privacy regulations.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Relay-aware PII scrubbers that redact sensitive spans before calling; confidential computing for teacher inference; auditable call logs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory approvals; cryptographic or enclave guarantees; graceful degradation when calls are prohibited.

- Hardware–software co-design for relay decoding

- Sectors: semiconductors, edge devices

- What: Architect accelerators and runtime schedulers optimized for pause/resume, context splicing, and micro-bursts to remote teachers.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Token-level preemption and streaming interconnects; memory-efficient context management (e.g., PagedAttention-like schemes tuned for relay).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Industry adoption of relay patterns; benchmarks capturing pause/resume overheads.

- Policy frameworks for cost-aware, low-carbon AI operations

- Sectors: public policy, sustainability, enterprise governance

- What: Encourage token-efficient hybrid inference (e.g., call-ratio targets) to reduce compute spend and carbon footprint while preserving service quality.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Procurement criteria referencing call ratio/accuracy trade-offs; standardized reporting of relay metrics; incentives for edge-first deployments.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable measurement; consensus metrics; lifecycle carbon accounting for cloud/offload segments.

- Robust relay strategies for non-verifiable tasks

- Sectors: creative work, general knowledge, open-ended chat

- What: Extend difficulty-aware rewards beyond deterministic verifiers using preference models, weak judges, or uncertainty estimators.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- RL from human/AI feedback tailored to relay decisions; confidence-triggered calling; hybrid judges to reduce gaming.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Noise-tolerant training; guardrails against judge exploitation; continuous evaluation to prevent regressions.

Notes on feasibility and dependencies across applications:

- Verifiable rewards (e.g., math/code checkers) substantially simplify RL training; for non-verifiable domains, expect more engineering for feedback signals.

- Teacher consistency matters: performance peaks when the inference teacher matches the training teacher; swapping teachers can degrade results unless adapted.

- Data filtering to remain within the teacher’s competence boundary avoids wasteful calls during training and improves cost–accuracy trade-offs.

- Dynamic call-length prediction is more efficient than fixed budgets; however, systems must handle additional pause/resume overhead and streaming synchronization.

- Privacy and compliance require careful selection/redaction of relayed context and auditable logging of call events.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.