Block-Recurrent Dynamics in Vision Transformers

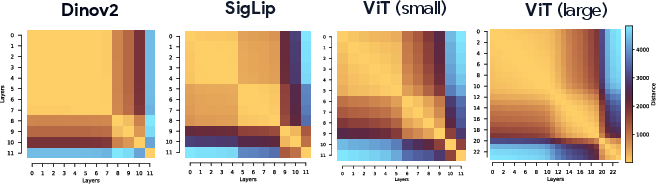

Abstract: As Vision Transformers (ViTs) become standard vision backbones, a mechanistic account of their computational phenomenology is essential. Despite architectural cues that hint at dynamical structure, there is no settled framework that interprets Transformer depth as a well-characterized flow. In this work, we introduce the Block-Recurrent Hypothesis (BRH), arguing that trained ViTs admit a block-recurrent depth structure such that the computation of the original $L$ blocks can be accurately rewritten using only $k \ll L$ distinct blocks applied recurrently. Across diverse ViTs, between-layer representational similarity matrices suggest few contiguous phases. To determine whether these phases reflect genuinely reusable computation, we train block-recurrent surrogates of pretrained ViTs: Recurrent Approximations to Phase-structured TransfORmers (Raptor). In small-scale, we demonstrate that stochastic depth and training promote recurrent structure and subsequently correlate with our ability to accurately fit Raptor. We then provide an empirical existence proof for BRH by training a Raptor model to recover $96\%$ of DINOv2 ImageNet-1k linear probe accuracy in only 2 blocks at equivalent computational cost. Finally, we leverage our hypothesis to develop a program of Dynamical Interpretability. We find i) directional convergence into class-dependent angular basins with self-correcting trajectories under small perturbations, ii) token-specific dynamics, where cls executes sharp late reorientations while patch tokens exhibit strong late-stage coherence toward their mean direction, and iii) a collapse to low rank updates in late depth, consistent with convergence to low-dimensional attractors. Altogether, we find a compact recurrent program emerges along ViT depth, pointing to a low-complexity normative solution that enables these models to be studied through principled dynamical systems analysis.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about

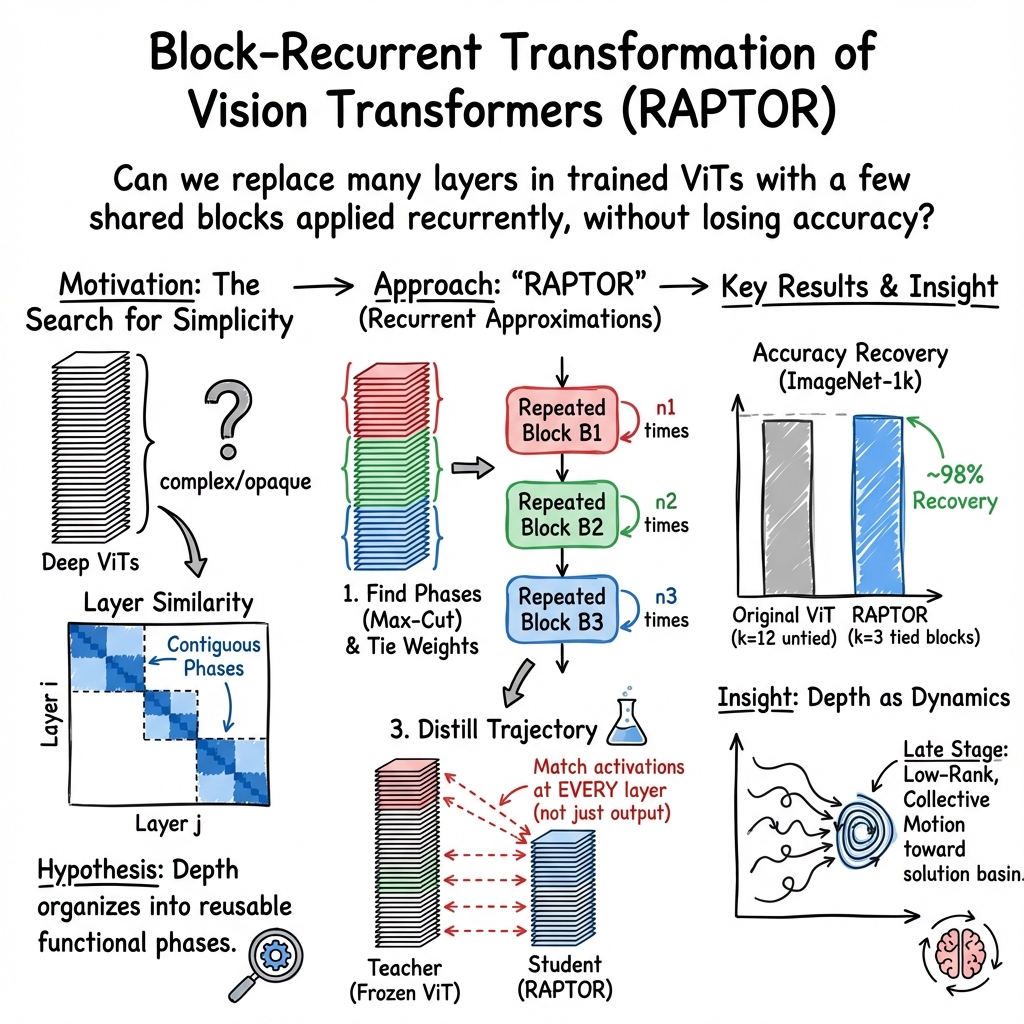

This paper studies how Vision Transformers (ViTs)—a kind of AI model that looks at images—actually do their work across their many layers. The big idea is that, even though ViTs have lots of layers, they seem to reuse the same few “kinds of steps” again and again. The authors call this the Block-Recurrent Hypothesis (BRH): after training, a ViT’s many layers can be grouped into a few phases, and each phase repeats the same block of computation multiple times.

Think of a ViT like an assembly line with many stations. The paper argues that, in practice, the assembly line is really made of just a few kinds of stations repeated in chunks, rather than every station being unique.

The main questions the paper asks

- Do ViTs naturally organize their layers into a small number of phases, where each phase repeats the same kind of computation?

- If we replace the many distinct layers with just a few shared “blocks” that we loop through, can we still get almost the same results?

- What do these repeated computations look like as a “dynamical system”—that is, like a process that evolves step by step over time?

How the researchers tested their ideas

First, a few simple translations of technical terms:

- Layer: one step in the model’s processing pipeline.

- Block: a chunk of layers that acts like one repeated unit.

- Recurrent: reusing the same block multiple times, like looping through the same step.

- Token: a piece of the input the model processes; in images, “patch tokens” represent image patches, and a special “cls token” acts like a team leader that summarizes everything.

- Similarity matrix: a grid that shows how similar the model’s internal representations are between different layers.

Here’s the approach, using everyday analogies:

- Spotting phases in depth

- The authors computed how similar each layer’s internal representation is to every other layer’s (imagine a heatmap where bright squares mean “very similar”).

- They consistently saw the depth divide into clear blocks—contiguous chunks of layers that are very similar—across many ViTs. This hinted at phases.

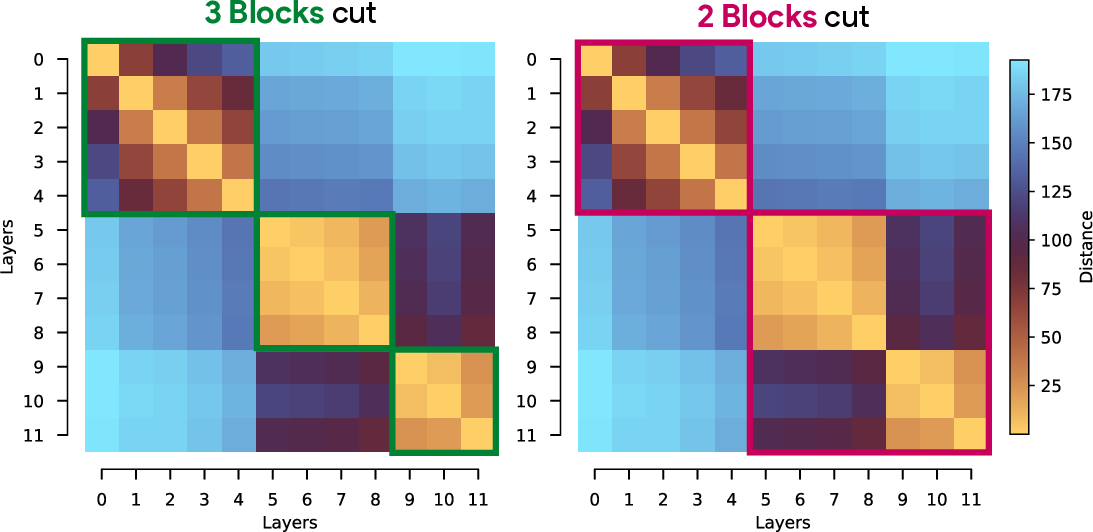

- Finding the phase boundaries

- They used a simple algorithm to cut the heatmap into contiguous blocks that maximize similarity within blocks and reduce similarity across blocks. You can think of this like slicing a music playlist at points where the style changes, so each slice is consistent inside.

- Building a “recurrent” stand-in model (RAPTOR)

- They created a new model called RAPTOR (Recurrent Approximation to Phase-structured Transformer). Instead of having L separate layers, RAPTOR uses just k distinct blocks and reuses them the right number of times per phase.

- Crucially, RAPTOR is trained to match the original model’s internal states at every layer step, not just the final prediction. This is like recreating the original path through the maze, not just ending at the same exit.

- Training RAPTOR safely and stably

- Teacher forcing: First, they trained each block using the original model’s hidden states as “ground truth inputs,” reducing early mistakes. Analogy: learning a dance by following a teacher step by step in place.

- Autoregressive training: Then they switched to letting RAPTOR feed its own outputs back in, so it works on its own at test time. Analogy: now dance without the teacher guiding your feet.

- They combined both, starting with teacher forcing and gradually shifting to fully autoregressive training for stability and realism.

- Testing what makes phases stronger

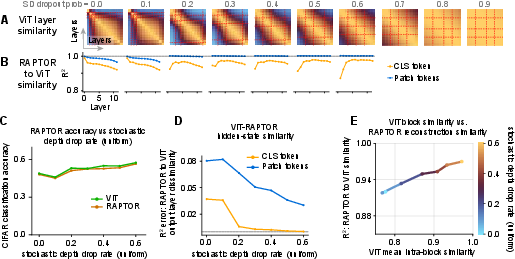

- They trained small ViTs with “stochastic depth” (randomly dropping layers during training). This made neighboring layers more similar and made RAPTOR’s job easier—supporting the idea that certain training choices encourage phase-like, reusable computation.

What they found and why it matters

- Strong evidence for phases and reuse

- Across many ViTs, layers naturally clustered into a few contiguous phases.

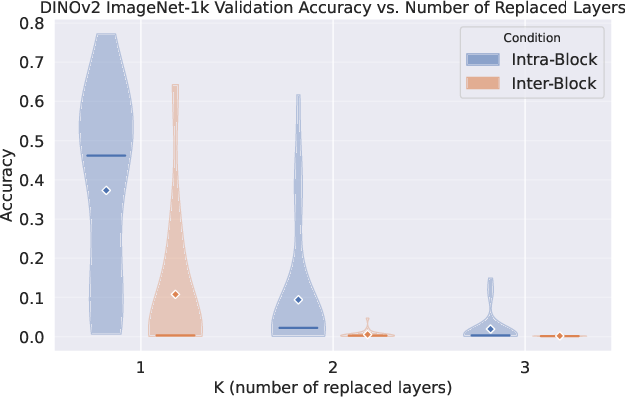

- Swapping layers within a phase usually worked, but swapping across phases broke the model—meaning each phase is functionally distinct.

- With only 2–3 shared blocks, RAPTOR could reproduce the original ViT’s internal states and performance very closely, not just the final outputs.

- It scales to big models

- On DINOv2 (a popular, high-performing ViT), a RAPTOR with just 2 blocks recovered about 96% of ImageNet-1k accuracy with the same compute budget; with 3 blocks, about 98%. That’s a strong “existence proof” that the original model’s depth is reusing a small set of computations.

- Training tricks matter

- Teacher forcing alone wasn’t enough; the model collapsed at test time. Adding autoregressive training fixed that.

- Extra details helped, like giving the “cls token” a bit more weight in the loss at the end and giving blocks a sense of “which step of the phase” they’re on.

- Looking at ViTs as step-by-step dynamics

- The authors analyzed how the model’s internal vectors evolve “over time” (layer by layer), focusing on directions rather than sizes.

- They saw “directional convergence”: token directions stabilize toward class-dependent “angular basins,” and small disturbances are corrected as processing continues. In plain terms: the model’s internal signals settle into stable, class-specific directions and shrug off small noise near the end.

- Different tokens behave differently:

- cls token (the “team leader”) makes sharp, late adjustments near the end to finalize the summary.

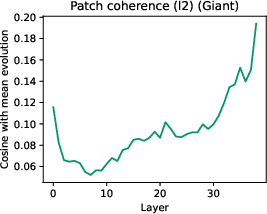

- Patch tokens (the “team members”) become strongly aligned late on, moving together like a crowd following a common direction.

- Updates in late layers become low-rank, meaning the model’s changes mostly happen in a few important directions. This suggests that the model has learned to focus its attention on a small number of crucial patterns late in processing.

Why this matters:

- It shows that ViTs’ depth hides a simpler repeated algorithm underneath. This makes them easier to understand, test, and possibly improve.

- It suggests we can design models that are lighter in parameters (fewer unique blocks) but keep the same runtime by reusing blocks—potentially making training and interpretation easier without slowing down inference.

What this could change or enable

- Better interpretability: If ViTs are really a few repeated steps, we can study those steps carefully, like understanding a short recipe rather than a long list of unique instructions.

- Safer and more reliable AI: Repeated, simpler computation may be easier to check, diagnose, and verify.

- Smarter model design: Future ViTs could be built with intentional phases and shared blocks, saving parameters while keeping speed, or even improving stability.

- New analysis tools: Treating depth like time opens the door to using dynamical systems methods to explain, test, and even control model behavior.

In one sentence

Even though Vision Transformers look deep and complex, this paper shows they behave like a small, repeated program running in phases—making them simpler, more interpretable, and still highly effective.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following list summarizes what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, phrased to enable concrete follow-up work:

- Formal conditions under which the Block-Recurrent Hypothesis (BRH) provably holds: characterize architectural features, training regimes, data distributions, and optimization dynamics that guarantee contiguous phases with bounded approximation error (i.e., derive sufficient/necessary conditions and explicit bounds on , , and ).

- Model selection for the number of blocks: develop principled criteria (e.g., validation objectives, MDL-like criteria, stability metrics) for choosing automatically, rather than fixing .

- Alternative phase discovery algorithms: compare max-cut segmentation to change-point detection, spectral clustering, Bayesian segmentation, and attention-map-based methods; assess sensitivity to initialization, seeds, and noise; quantify stability of discovered boundaries.

- Non-contiguous recurrence and conditional reuse: test whether functionally similar layers might form non-contiguous phases or input-conditional segments; evaluate dynamic routing/gating across blocks at inference (per input or per class).

- Generality across architectures and modalities: validate BRH and RAPTOR on ViT-L/G, hierarchical ViTs (Swin), conv-attention hybrids, CLIP, MAE, diffusion backbones, segmentation-specific ViTs, and video transformers with temporal attention.

- Task coverage beyond linear probes: assess RAPTOR under end-to-end fine-tuning, detection (e.g., COCO), instance segmentation, keypoint estimation, retrieval, and zero-shot transfer; quantify performance gaps when the backbone is unfrozen.

- Out-of-distribution robustness and stability: evaluate RAPTOR vs. the teacher under distribution shift (e.g., ImageNet-A/C/R), adversarial perturbations, corruptions, and rare classes; test whether block recurrence preserves or degrades robustness.

- Functional equivalence beyond activation matching: design causal tests (e.g., targeted ablations, counterfactual interventions, gradient alignment, attention pattern similarity) to verify that matched activations imply matched computations, not just representational mimicry.

- Training-from-scratch with tied blocks: investigate whether ViTs trained end-to-end with weight-tied blocks (Universal-Transformer-style) can reach DINOv2-level performance without distillation from an untied teacher; compare training stability, sample efficiency, and final accuracy.

- Partial parameter tying: determine which subcomponents (self-attention, MLP, layernorms, residual scales) can be tied without loss; map which parts drive recurrence and which require depth-specific specialization.

- Mechanistic origin of phases: connect phase boundaries to training dynamics (e.g., learning-rate schedule, optimization curvature, loss landscape transitions), architectural hyperparameters (heads, hidden width, positional embeddings), and representational geometry.

- Stochastic depth variants: extend analysis to non-uniform per-layer SD schedules, combination with dropout and DropPath, interactions with weight decay and strong augmentation; isolate causal factors behind aberrant training at high SD rates (0.7–0.9).

- Norm growth and normalization effects: explain the observed monotonic norm increase (e.g., role of pre-norm/post-norm, residual scaling, layernorm statistics); test normalization schemes or residual scaling that stabilize norms while preserving angular convergence.

- Attention-head and token-type granularity: characterize head-level recurrence, per-head phase boundaries, and specialization; study models without cls or register tokens (e.g., avg-pool readout) to determine whether token-specific dynamics and phase structure persist.

- Per-class and input-conditional phase structure: measure whether phase boundaries and angular attractors vary by class, scene type, or input statistics; explore class-conditional RAPTOR schedules or adaptive phase selection at test time.

- Low-rank update collapse: provide theoretical explanation for the observed late-depth low-rank dynamics (stable/effective rank ~6), relate to attention kernel spectra, mean-field analyses, and contraction properties; quantify how rank depends on architecture and training.

- Levin complexity claim under -BRH: extend the provided 0-BRH bound to realistic -BRH; derive explicit dependence of Levin complexity on approximation error and runtime parity deviations; empirically estimate description length reductions.

- Compute, memory, and energy parity: move beyond iso-FLOPs to measure wall-clock latency, memory bandwidth, cache behavior, and energy consumption of weight-tied recurrence vs. untied teachers across hardware (GPU/TPU/CPU); assess deployment trade-offs.

- Comparison to standard compression/distillation: benchmark RAPTOR against pruning, factorization, quantization, LoRA/adapters, and classical distillation (logit/feature hints) under equal compute budgets; identify regimes where block recurrence is preferable.

- Scaling law for recurrence: quantify how scales with depth and model size; test whether recurrence saturates (e.g., ) across families; derive predictors (e.g., block-similarity metrics) for expected .

- Attention map and circuit-level interpretability: link angular basins and phase-local dynamics to interpretable circuits (e.g., class-specific features, heads that gate phase transitions); test whether phase transitions correspond to semantic stage shifts.

- Causal layer-swapping granularity: go beyond layer swaps to sublayer/component swaps (attention vs. MLP, Q/K/V projections) within and across phases; identify minimal functional units whose identity is unique to each phase.

- Robustness of phase boundaries over training: track phase structure across training checkpoints in large-scale models (not just CIFAR toy ViTs); determine when phases crystallize and how overfitting or regularization shifts boundaries.

- Register token dependence: DINOv2 uses register tokens—evaluate whether BRH and dynamical findings hold in models without registers; quantify their contribution to stability, coherence, and low-rank collapse.

- Dynamic test-time compute: integrate block recurrence with conditional early-exit or iterative refinement policies; assess whether adaptive iteration counts per input improve accuracy/efficiency while preserving phase-consistent dynamics.

- Attention to practical constraints of activation supervision: characterize the memory/computation overhead of matching all intermediate activations; propose scalable approximations (e.g., subset of layers, projected states, sketching) that retain RAPTOR fidelity.

- Safety and formal verification: explore whether block recurrence simplifies verification (e.g., certifying bounded deviations under perturbations) and enables interpretable safety guarantees for vision models.

Glossary

- ADE20k: A widely used semantic segmentation dataset for evaluating vision models. "ADE20k (semantic segmentation)"

- Angular attractor: A stable directional state on the unit sphere toward which token representations converge through depth. "We interpret these regions as angular attractors"

- Autoregressive loss (AR): A training objective where the model’s next-layer prediction is conditioned on its own previous predictions to match a teacher’s intermediate activations. "We train \raptor~using an autoregressive loss (AR) that enforces trajectory fidelity across all intermediate layers:"

- Block-diagonal structure: A pattern in similarity matrices where contiguous layers form high-similarity blocks, indicating phases along depth. "representational similarity matrices consistently exhibit block-diagonal structure across disparate models."

- Block-Recurrent Hypothesis (BRH): The claim that a ViT’s depth can be rewritten using a small number of distinct blocks applied recurrently while preserving intermediate activations. "we introduce the Block-Recurrent Hypothesis (BRH)"

- CLIP: A multimodal foundation model that learns visual features aligned with text. "DINOv2 \citep{oquab2023dinov2,darcet2023vision} and CLIP \citep{radford2021learningtransferablevisualmodels}"

- Cosine similarity: A directional similarity measure between vectors used to compare representations across layers. "we construct layer-layer similarity matrices by computing the cosine similarity of each token at layer with the same token at layer ."

- DINOv2: A strong self-supervised vision transformer framework used as a teacher model. "DINOv2 \citep{oquab2023dinov2,darcet2023vision}"

- Discrete-time dynamical system: A view of model depth as iterative updates over layers, enabling dynamical analysis. "treats ViT depth as the discrete-time unfolding of an underlying dynamical system"

- Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD): A linearization technique that extracts dominant dynamical modes from temporal data. "We then linearize the depth flow via exact DMD"

- Dynamic programming: An optimization approach used here to segment depth into contiguous blocks via max-cut. "solved via dynamic programming (see \cref{app:maxcut} for details)."

- Dynamical interpretability: Analyzing model computations through the lens of dynamical systems to understand representational evolution. "we leverage our hypothesis to develop a program of Dynamical Interpretability."

- Dynamical systems: Mathematical frameworks for studying the evolution of states under iterative updates, linked to residual networks. "Residual connections have long suggested a link to dynamical systems"

- Effective rank: A measure of the dimensionality of updates that decreases with depth, indicating low-dimensional dynamics. "Both the stable rank and effective rank decrease steadily with depth"

- Frobenius norm: A matrix norm used to quantify layerwise activation reconstruction error. "Here, denotes the Frobenius norm"

- ImageNet-1k: A large-scale image classification benchmark used for linear probing. "ImageNet-1k (classification)"

- Iso-FLOPs: Matching computational cost (floating-point operations) while changing architecture, e.g., tied blocks vs. untied layers. "a two-block \raptor~at iso-FLOPs retains about of DINOv2 ViT\text{-}B"

- Kolmogorov complexity: A measure of description length; here contrasted with runtime-preserving compression. "more subtle than standard Kolmogorov complexity~\citep{kolmogorov1965three}."

- Layer–layer similarity: Pairwise comparison across depth that reveals phases in representation. "Layerâlayer similarity matrices across diverse Vision Transformers reveal block-structure."

- Levin’s complexity: Description length accounting for runtime; used to argue for compact programs at unchanged computational cost. "aligning more closely with Levin's complexity $K_{\text{Levin}$~\citep{levin1973universal}"

- Linear probe: A frozen-backbone evaluation method that trains a linear classifier on learned features. "training linear probes on ImageNet-1k (classification)"

- Low rank: The phenomenon that layer-to-layer updates collapse to a small number of directions in late depth. "a collapse of the update to low rank in late depth"

- Max-cut: A partitioning formulation used to discover contiguous phase boundaries in similarity matrices. "casting this ``block discovery'' process as a weighted max-cut problem"

- Mean-field effect: Collective behavior of patch tokens aligning strongly and moving coherently late in depth. "reminiscent of a mean-field effect"

- mIoU: Mean Intersection-over-Union; a standard metric for semantic segmentation performance. "mean Intersection-over-Union (mIoU)"

- Non-autonomous dynamical system: A system whose update depends explicitly on iteration count (depth), not just state. "making \raptor~a non-autonomous dynamical system"

- Parameter tying: Reusing the same parameters across multiple applications of a block to induce recurrence. "parameter-tied block $\B_j$"

- Patch tokens: Per-patch embeddings in ViTs that exhibit coherent collective dynamics in later layers. "patch tokens exhibit strong late-stage coherence"

- PCA: Principal Component Analysis; used to visualize trajectories and class-dependent basins in a low-dimensional subspace. "PCA reveals that sample-specific paths enter class-dependent basins"

- RAPTOR (Recurrent Approximations to Phase-structured Transformers): A weight-tied recurrent surrogate trained to match a ViT’s entire activation trajectory. "which we call \p{R}ecurrent \p{A}pproximations to \p{P}hase-structured \p{T}ransf\p{OR}mers (\raptor)."

- Representational similarity matrix: A matrix comparing layerwise representations that reveals contiguous phases. "layerâlayer representational similarity matrices consistently exhibit block-diagonal structure"

- Registers (tokens): Special tokens that act as stabilizing anchors with small angular speeds and long memory. "for cls, registers, and patch"

- RMSE: Root Mean Squared Error; a standard regression metric used here for depth estimation. "root mean squared error (RMSE) on NYUv2 depth estimation."

- Self-correcting trajectories: Dynamics that bend perturbed paths back toward the nominal trajectory, indicating local stability. "self-correcting trajectories under small perturbations"

- Stochastic depth: Training regularization that randomly drops layers to encourage robustness and block recurrence. "stochastic depth \citep{huang2016deepnetworksstochasticdepth}"

- Teacher forcing: A training scheme where the model is fed ground-truth activations at each step to stabilize learning. "teacher forcing trains each block to predict the immediate next layer"

- Token-specific dynamics: Distinct angular behaviors for different token types (cls, registers, patches) across phases. "token-specific dynamics, where cls executes sharp late reorientations while patch tokens exhibit strong late-stage coherence"

- Vision Transformers (ViTs): Transformer architectures adapted to images that process sequences of tokens from patches. "Vision Transformers (ViTs)"

- Weight-tied: Sharing parameters across repeated block applications to implement recurrence. "weight-tied block-recurrent approximations of pretrained ViTs"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The paper’s findings can be operationalized today in multiple settings. Below is a prioritized set of concrete applications, each with sector mapping and feasibility notes.

- Recurrent approximations (RAPTOR) for ViT backbones with parameter tying

- Sectors: software/ML infrastructure, edge/embedded AI, robotics, mobile, AR/VR

- What: Convert pretrained ViTs into weight-tied, block-recurrent surrogates (RAPTOR) that preserve internal trajectories and retain 96–98% of DINOv2-B linear-probe accuracy with 2–3 blocks at iso-FLOPs. This reduces unique parameters while maintaining compute.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- RAPTOR training pipeline (teacher-forcing + autoregressive training with annealing)

- Pre-built conversion scripts for popular ViTs (e.g., DINOv2-B)

- Frozen-backbone linear probe workflows for classification, segmentation, depth

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Access to teacher model intermediate activations and weights (for activation-level distillation)

- Similarity structure present in the target ViT (empirically shown for DINOv2 and smaller ViTs)

- Inference runtime is likely unchanged; gains are primarily parameter memory and bandwidth

- Memory- and bandwidth-efficient deployment of ViTs via weight sharing

- Sectors: edge/embedded AI, robotics, automotive, healthcare devices, mobile

- What: Fewer unique parameters reduce model size and DRAM traffic, improving memory footprint and on-device energy use without sacrificing inference accuracy or latency.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- “BR-ViT” variants with tied blocks for resource-constrained deployment

- Inference engines that cache and reuse tied block kernels efficiently

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Hardware/software stack can exploit weight reuse to reduce memory bandwidth

- No FLOPs reduction unless iterations are adapted (see long-term)

- Phase discovery for model understanding, debugging, and maintenance

- Sectors: software/ML tooling, MLOps, safety-critical domains (automotive, healthcare)

- What: Use the max-cut segmentation on layer–layer similarity matrices to identify contiguous computational phases; validate with intra-/inter-block layer swap tests.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- “PhaseCut” analyzer: contiguous phase boundary detection from activations

- Layer-swap diagnostics to check phase fidelity and detect regressions

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Availability of layerwise activations on a representative dataset

- Phase structure is stable across inputs and persists post fine-tuning (empirically likely, but should be checked)

- Training regularization to promote recurrent compressibility

- Sectors: academia, software/ML training, platform model teams

- What: Use stochastic depth during training to increase layer–layer similarity and facilitate accurate RAPTOR fitting, with improved accuracy in both teacher and student.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Training recipes: stochastic-depth schedules (avoid very high rates that cause instability)

- Early diagnostics linking representational similarity to compressibility

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Training stability (extreme stochastic depth p can be unstable)

- Applicability depends on objective and data regime

- Dynamical interpretability dashboards for ViTs

- Sectors: safety/assurance, regulated industries, research, MLOps

- What: Operational metrics to monitor “depth-as-dynamics”: angular convergence to attractors, token-specific angular speeds, low-rank collapse in late depth, and perturbation self-correction.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Dashboards tracking cosine-to-final-direction curves, effective/stable rank of updates, patch coherence, and sensitivity under small perturbations

- CI/CD hooks to flag deviations from expected dynamical signatures during model updates

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Access to activations; model exposes token representations (e.g., cls, patch tokens)

- Deployment teams accept dynamical metrics as model health indicators

- Robustness and QA checks using trajectory sensitivity

- Sectors: healthcare imaging, autonomous systems, industrial inspection

- What: Use “self-correction” and phase-local contraction as qualitative indicators for stability. Flag samples where trajectories fail to converge directionally or show atypical sensitivity.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Outlier detection based on angular trajectory divergence from reference basins

- Pre-deployment audit reports using per-token/phase sensitivity

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- No formal guarantees yet; this is a practical QA heuristic (not a certification)

- Academic workflows for mechanistic and dynamical analysis of ViTs

- Sectors: academia, research labs

- What: Treat ViT depth as discrete-time dynamics; apply PCA trajectory analysis, dynamic mode decomposition (DMD), and low-rank diagnostics for mechanistic insight.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Reproducible notebooks for DMD on token groups, angular attractor mapping, phase-aware analyses

- Benchmarks linking phase structure to RAPTOR fit quality

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Standard ViT architectures with residual updates and tokenization

- CLS or equivalent aggregator available (or adapted metrics for pooling-based models)

- Model size–accuracy trade-offs for dense prediction with RAPTOR backbones

- Sectors: vision applications (segmentation, depth)

- What: Deploy RAPTOR backbones with frozen weights and linear heads; expect modest degradation vs. teacher (e.g., ADE20K mIoU drop relative to ViT-B) but potential gains over ViT-S baselines with fewer parameters.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Head-only fine-tuning pipelines for segmentation/depth with RAPTOR features

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Some tasks (dense prediction) may be more sensitive to recurrence; validate per use case

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities build on the paper’s methods and empirical insights, but require further R&D, scaling work, or ecosystem changes.

- Recurrent-first ViT architectures with adaptive iteration

- Sectors: software/ML infrastructure, robotics, automotive, mobile

- What: Architectures explicitly designed with a small number of shared blocks and a learned controller for iteration counts per phase, enabling accuracy–latency trade-offs at test time (akin to Universal Transformers, now supported by BRH evidence).

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Controllers for dynamic depth/iterations per input or per token

- Hardware-aware schedulers to balance accuracy vs. energy

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Training stability for non-autonomous recurrent updates

- Hardware support for fine-grained dynamic control and caching

- Phase-aware quantization, pruning, and compilation

- Sectors: edge/embedded AI, cloud inference, compilers

- What: Apply different compression regimes per phase (e.g., stronger quantization in late low-rank phases), or compile tied blocks to specialized kernels with improved cache locality and reduced memory traffic.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Phase-conditioned post-training quantization and pruning recipes

- Compiler passes that fuse and schedule recurrent blocks efficiently

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Robust phase detection and stability across datasets and fine-tuning

- Toolchain support for recurrent weight-tying patterns

- Verification and assurance using dynamical systems lenses

- Sectors: healthcare, aerospace, automotive, policy/regulation

- What: Develop certifiable tests leveraging angular attractor convergence, phase-local contraction, and low-rank late updates to define “normal operating regimes.” Use these to constrain behavior and support audits.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Formalized “dynamical conformance tests” for safety audits

- Phase-level acceptance criteria for updates/fine-tunes

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Theory linking dynamical metrics to risk (currently empirical)

- Regulator and standards-body acceptance

- Algorithmic complexity–aware model selection and training objectives

- Sectors: platform model teams, academia

- What: Introduce penalties or priors that encourage low Levin complexity via block recurrence and shared computation, favoring compact algorithmic programs at iso-runtime.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Regularizers that encourage representational phase structure and parameter tying

- Model selection criteria based on compressibility by RAPTOR

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Measurable link between compressibility and generalization/robustness across domains

- Continual learning and fast domain adaptation via phase-local updates

- Sectors: enterprise vision, robotics, defense

- What: Fine-tune only specific phases or add small adapters per phase to adapt to new domains with minimal forgetting and small parameter deltas.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Phase-specific adapters, prompts, or LoRA modules

- Phase-targeted early stopping and regularization

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Phase identity remains meaningful after multiple domain shifts

- Adapter placement interacts predictably with phase dynamics

- Test-time diagnostics and anomaly detection using trajectory deviations

- Sectors: healthcare imaging, industrial inspection, finance/biometrics

- What: Monitor angular trajectories and low-rank patterns at inference; flag inputs whose dynamics diverge from known basins as potential OOD or attack candidates.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Online monitors of cosine-to-final-direction curves and patch coherence

- Alerting systems tied to per-phase sensitivity thresholds

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Robust calibration to minimize false positives

- Privacy/safety constraints for logging internal activations

- Cross-modal and multimodal extensions (e.g., LMMs, video)

- Sectors: media, surveillance, autonomous systems, education

- What: Apply BRH and RAPTOR concepts to video transformers and multimodal encoders; exploit phase structure in temporal tokens and cross-modal attention.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Phase discovery on spatiotemporal layers

- Recurrent approximations with modality-specific phases

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Empirical validation in non-vision or multimodal settings

- Task-dependent retention of accuracy under recurrence

- Curriculum/training pipelines that target desired phase structure

- Sectors: academia, platform model teams

- What: Shape training to encourage clean phase boundaries and low-rank late dynamics (e.g., stochastic depth schedules, phase-wise pretraining), improving interpretability and recurrent compressibility.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Phase-aware training curricula; staged untying-to-tying schedules

- Early stopping keyed to dynamical metrics (e.g., rank collapse, angular convergence)

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Reliability of dynamical proxies during training

- No adverse effects on downstream performance

- Policy measures for transparency and accountability

- Sectors: policy/regulation, safety-critical industries

- What: Require disclosure of phase structure, compressibility metrics, and dynamical signatures as part of model documentation; use phase-aware tests during certification.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Reporting standards for representational similarity matrices and phase partitions

- Checklists for dynamical interpretability indicators

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Policy acceptance; alignment with emerging AI assurance standards

Notes on feasibility and limitations

- Compute vs. memory: RAPTOR retains FLOPs (iso-runtime by design) but cuts unique parameters, which can reduce memory bandwidth and energy; latency gains require further engineering (e.g., adaptive iteration or compiler support).

- Task variability: Classification retains 96–98% with 2–3 blocks; dense prediction shows moderate drops versus ViT-B (still competitive vs. ViT-S). Validate per application.

- Data/model access: Most immediate applications require access to teacher activations to fit RAPTOR and to compute layer-similarity matrices.

- Architectural assumptions: Results rely on ViT-like residual architectures and tokenization (with cls or equivalent); adaptations needed for architectures without cls or with different pooling schemes.

- Stability: Extremely high stochastic depth rates can harm training; robust schedules and monitoring are necessary.

- Guarantees: Dynamical metrics are currently empirical indicators (useful for QA and audits) rather than formal safety guarantees. Further theory and standardization are needed for certification-grade use.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.