Pessimistic Verification for Open Ended Math Questions (2511.21522v1)

Abstract: The key limitation of the verification performance lies in the ability of error detection. With this intuition we designed several variants of pessimistic verification, which are simple workflows that could significantly improve the verification of open-ended math questions. In pessimistic verification we construct multiple parallel verifications for the same proof, and the proof is deemed incorrect if any one of them reports an error. This simple technique significantly improves the performance across many math verification benchmarks without incurring substantial computational resources. Its token efficiency even surpassed extended long-CoT in test-time scaling. Our case studies further indicate that the majority of false negatives in stronger models are actually caused by annotation errors in the original dataset, so our method's performance is in fact underestimated. Self-verification for mathematical problems can effectively improve the reliability and performance of LLM outputs, and it also plays a critical role in enabling long-horizon mathematical tasks. We believe that research on pessimistic verification will help enhance the mathematical capabilities of LLMs across a wide range of tasks.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about helping AI check math proofs more reliably. When students (or AI) solve “open‑ended” math problems, they write step‑by‑step explanations instead of just giving a number. The big challenge is verifying whether those steps are really correct. The authors introduce a simple but powerful idea called “pessimistic verification” to catch mistakes in these written solutions more effectively.

What problem are they trying to solve?

- AI models can solve and grade many math problems, but they often miss hidden errors in long, open‑ended solutions.

- Current ways to improve checking (like making the AI “think longer” or using majority voting) don’t consistently help find mistakes.

- The paper asks: Can we design a simple, efficient way to make AI better at spotting errors in math proofs?

How does their method work?

Think of grading a math solution like having multiple careful teachers review it. “Pessimistic verification” means:

- You ask several “teacher” checks (or different kinds of checks) on the same solution.

- If any one check finds an error, you mark the solution as incorrect.

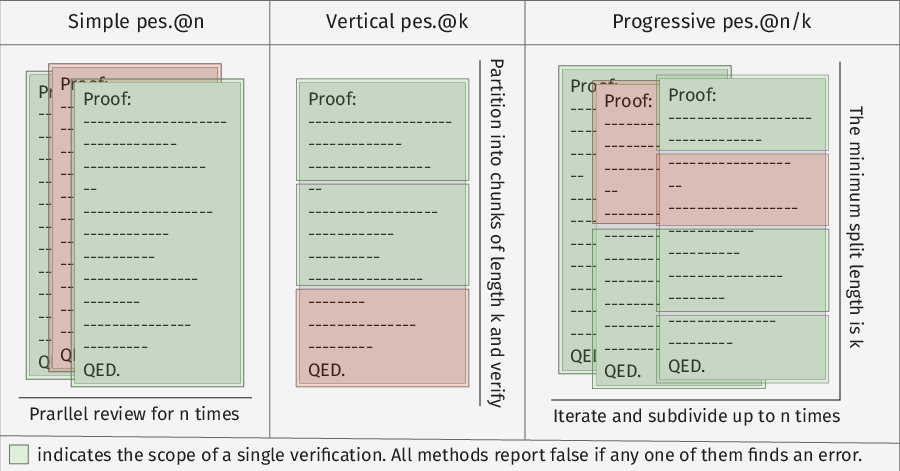

The authors test three versions, each like a different review style:

- Simple: Review the whole proof several times, independently. If any review finds an error, it’s wrong.

- Vertical: Split the proof into small chunks (like every few lines) and zoom in on each chunk to look for local mistakes.

- Progressive: Start broad, then zoom in. First check the whole proof to weed out obvious errors. Then repeatedly split the remaining proof into halves and check each part more closely, stopping early when you find mistakes. This saves time by not overchecking proofs that already failed.

Everyday analogy: Imagine reading an essay to find errors.

- Simple: Read the entire essay multiple times. If any read spots a mistake, the essay fails.

- Vertical: Divide the essay into paragraphs and check each paragraph carefully.

- Progressive: First skim for obvious issues; if it passes, then split and zoom in (paragraphs, then sentences) until you’re sure.

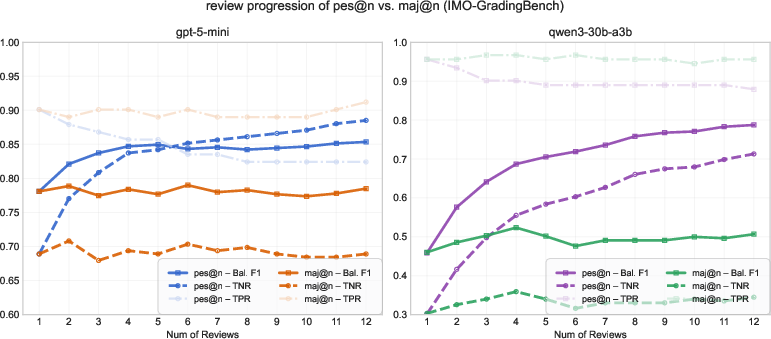

Majority voting (asking several reviewers and picking the most common opinion) was less helpful for catching errors, because often only one careful read will notice a subtle mistake. With pessimistic verification, that one “no” matters.

What did they do to test it?

They ran experiments with different AI models on three tough math datasets:

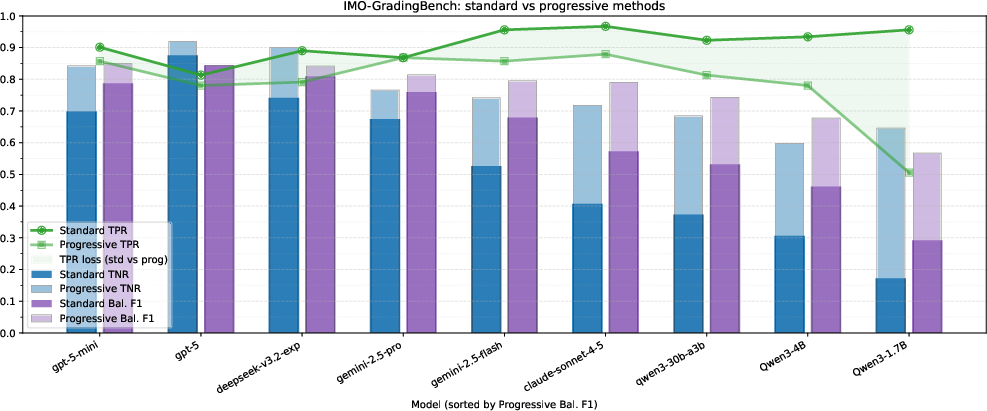

- IMO‑GradingBench: Human‑graded solutions to Olympiad‑level proof problems.

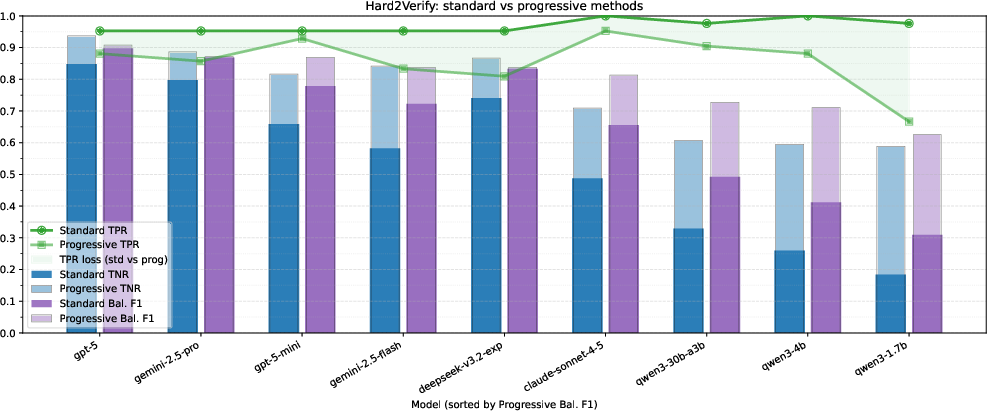

- Hard2Verify: Difficult competition problems with AI‑generated solutions and human labels.

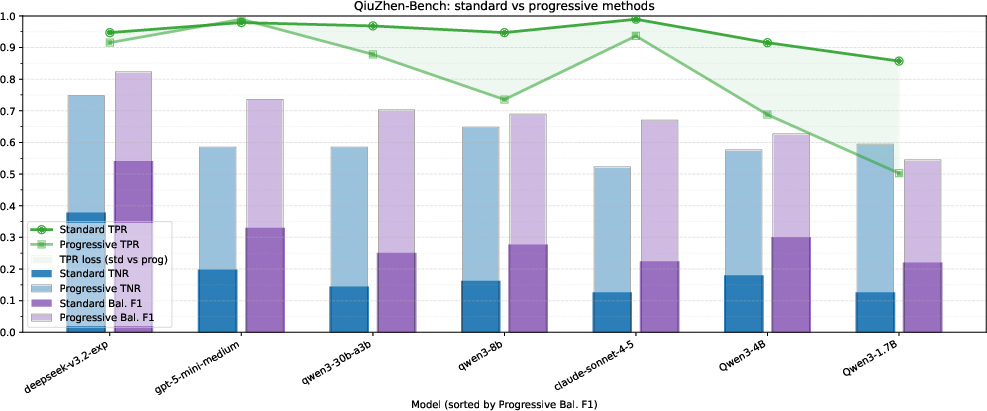

- QiuZhen‑Bench: A new dataset they created from advanced university‑level math exams (1,054 questions total; they evaluated a 300‑problem subset).

They measured:

- True Negative Rate (TNR): How well the AI spots incorrect proofs.

- True Positive Rate (TPR): How well the AI recognizes truly correct proofs.

- Balanced F1: A combined score that balances both catching bad proofs and accepting good ones.

They also looked at efficiency: how much extra “thinking” or tokens the AI needed.

Main findings and why they matter

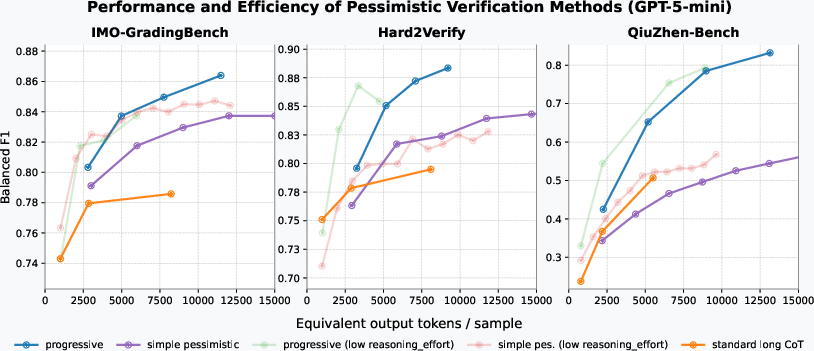

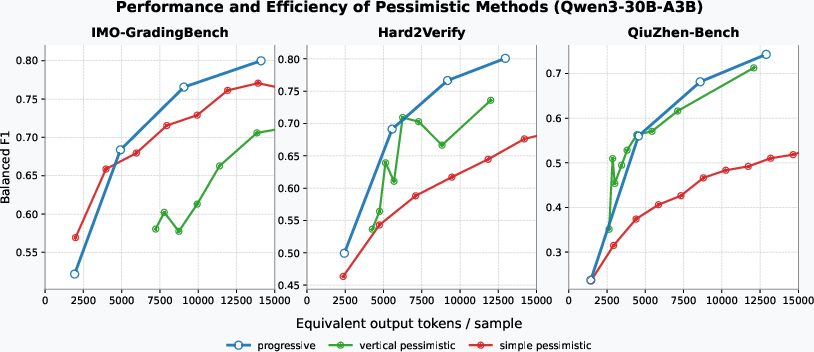

- Pessimistic verification boosts error detection (higher TNR) across models and datasets.

- The progressive version usually performs best and is very efficient. It scales better with extra checking than simply making the AI write longer explanations.

- Majority voting barely helps verification. In contrast, pessimistic checks consistently improve results.

- Parallel checks are faster than forcing one very long chain of reasoning.

- For strong models, many “false negatives” (marking a solution wrong when the dataset said it was right) were actually due to mistakes in the dataset’s labels. In other words, the model correctly found real errors that humans had missed. So the method’s true accuracy is probably even better than the scores show.

- They also release QiuZhen‑Bench, a high‑quality advanced math dataset useful for future research.

What’s the impact?

This method makes AI graders more cautious and thorough, which is good for:

- More reliable math solutions and grading, especially for long, complex proofs.

- Long‑horizon tasks (projects with many steps) where small errors can snowball.

- Training future AI models: you can use pessimistic verification inside training pipelines to push models toward more rigorous reasoning.

- Beyond math, similar ideas could help review code or other structured tasks where checking correctness is hard without running tests.

In short, pessimistic verification is a simple, smart way to make AI better at catching mistakes in open‑ended math proofs. It improves performance, saves time, and nudges AI toward producing truly rigorous work.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper—intended to guide future research.

- Lack of step-level evaluation: verification is assessed only at the response level; there is no systematic measurement of where errors occur, how well each method localizes them, or whether detected errors actually invalidate specific proof steps.

- Explanation validity is unmeasured: the verifier is required to provide an “explanation,” but the paper does not quantify the factual correctness, specificity, or reproducibility of these explanations across models and runs.

- Limited adjudication of false cases: the case paper on false negatives is small and limited to a subset of models/datasets; there is no comprehensive human adjudication of both false negatives and false positives across all conditions.

- Dataset label noise is asserted, not remedied: while the paper claims many FN cases reflect annotation errors, it does not (i) provide a systematic relabeling protocol, (ii) release a corrected benchmark, or (iii) quantify label quality via inter-annotator agreement.

- Circularity/bias in QiuZhen-Bench labeling: QiuZhen-Bench labels are produced by GPT-5 with progressive pessimistic verification, which risks embedding model-specific biases and verification heuristics into the ground truth; no independent human gold standard is provided.

- No inter-annotator agreement or rubric standardization: rigor criteria vary across datasets; the paper does not define a standardized grading rubric or measure agreement among human or model-based annotators.

- Hyperparameter sensitivity is underexplored: there is no thorough ablation of progressive@n/l and vertical chunk size l (e.g., sensitivity curves, robustness ranges, adaptive scheduling).

- Arbitrary segmentation by line count: vertical verification splits proofs by fixed line intervals, which may fracture logical steps; semantic segmentation (e.g., by claims/lemmas/inferences) is not explored.

- Temperature and sampling strategy effects: all experiments use temperature=1.0; the paper does not examine how sampling temperature, decoding strategies (e.g., nucleus/top-k), or diversity controls interact with pessimistic verification.

- Efficiency metrics omit wall-clock and system overhead: “equivalent output tokens” based on token pricing does not reflect actual latency, parallelization overhead, throughput under contention, memory-bandwidth constraints, or energy costs; real-time performance and scalability are unmeasured.

- No statistical significance testing: reported gains lack confidence intervals, variance estimates, or formal hypothesis tests; robustness across random seeds and runs is not assessed.

- Limited model diversity: results focus on GPT-5(-mini) and Qwen3-30B-A3B; generalization to broader open-weight models, smaller models, and multimodal/structured reasoning models is unclear.

- Majority voting dismissed without exploring stronger aggregators: beyond simple majority, alternative fusion strategies (e.g., weighted voting, error-calibrated aggregation, critique aggregation, multi-agent debate) are not evaluated for verification tasks.

- Calibration of strictness vs recall is unaddressed: pessimistic “OR-of-errors” increases TNR at the cost of TPR; there is no principled mechanism to tune strictness thresholds to task demands or user risk tolerance.

- No theoretical analysis of soundness/consistency: the paper offers no formal guarantees (e.g., bounds on false negative/false positive rates, conditions for consistency or completeness) under different verification budgets and data regimes.

- Adversarial robustness untested: the system’s vulnerability to adversarially crafted proofs (e.g., obfuscation, misleading structure, redundant steps, style attacks) or solver collusion is not evaluated.

- Scalability to very long proofs is uncertain: progressive verification’s worst-case checks grow as ; there is no analysis of memory limits, context fragmentation, or performance on proofs spanning thousands of tokens.

- Lack of adaptive budgeting: verification effort is fixed by n and l; active or adaptive strategies that allocate more reviews to uncertain segments or dynamically adjust chunking are not tested.

- Cross-domain generalization is speculative: applicability to code, natural language arguments, or scientific writing is claimed but not empirically validated or benchmarked.

- Integration with formal tools not compared: hybrid pipelines (e.g., natural-language pessimistic verification plus formal proof assistants) are not explored, and trade-offs versus formal provers are not quantified beyond anecdotal remarks.

- Training-time impacts remain untested: proposed use in RL/self-evolution pipelines is not implemented; there is no analysis of reward shaping, feedback loop stability, or whether pessimistic verification induces over-pessimism during training.

- Prompt transparency and reproducibility: full prompts and reviewer instructions (especially for vertical/progressive methods) are not included in the paper; reproducibility depends on external code and closed APIs.

- Class imbalance and distributional effects: pruning efficiency depends on the prevalence of negative examples, but the paper does not report class ratios per dataset or analyze performance under different imbalance levels.

- Data contamination checks are absent: there is no audit of potential training-test leakage for models on the chosen math datasets, which could inflate performance or affect verifier behavior.

- Comparison to recent specialized verifiers is limited: contemporary verification-focused models (e.g., Heimdall) and reward-model-based verifiers are not directly benchmarked against pessimistic verification under controlled budgets.

- Explanation quality metrics are missing: there is no standardized scoring for the clarity, minimality, and fixability of detected errors (e.g., does the explanation identify the smallest invalid inference and a concrete correction?).

- Effects on diverse proof styles: strict verification may penalize unconventional but valid proof styles; style robustness and bias (e.g., toward textbook phrasing) are not assessed.

- Decision policies for conflicting judgments: when different verification rounds flag incompatible errors or disagree, there is no meta-policy for reconciliation beyond the pessimistic OR.

- Safety and reliability in deployment: the paper does not address user-facing risks (e.g., undue rejection of correct solutions), audit trails, or accountability mechanisms for high-stakes use in education and research.

Glossary

- Agentic workflows: Multi-step, tool-using evaluation or grading pipelines where an LLM acts as an agent to structure and execute tasks. "Some of them proposed certain agentic workflows that could enhance this ability~\citep{mahdavi_refgrader_2025, mahdavi_scaling_2025}."

- Balanced F1 Score: A metric that balances sensitivity to both correctly accepted and correctly rejected items; the harmonic mean of TPR and TNR. "Balanced F1 Score: The harmonic mean of TPR and TNR, providing a balanced indicator of performance when both false positives and false negatives matter."

- Chain of thought: An LLM reasoning technique that produces explicit intermediate steps; longer chains often improve reasoning but at higher cost. "We proposed three variants of pessimistic verification methods that could significantly enhance the verification ability of LLMs with a higher efficiency than scaling long chain of thought."

- Formal theorem prover: A system (e.g., Lean) that checks mathematical proofs with full logical rigor in a formal language. "One possible solution to this problem is through formal theorem provers such as Lean~\citep{chen_seed-prover_2025, varambally_hilbert_2025}, which could provide completely reliable verification on math proofs."

- Ground-truth: Definitive, correct answers or labels used as a reference for training or evaluation. "They typically require math problems or code test cases that come with ground-truth answers, along with feedback functions that can be directly computed through explicit rules to complete the training."

- Hyperparameter: A user-set configuration value that controls an algorithm’s behavior (e.g., granularity or number of iterations). "Vertical pessimistic verification adopts a hyperparameter , it first splits the whole proof into chunks with lines, and create a series of parallel review tasks for each chunk."

- Large Reasoning Models (LRMs): LLMs specifically trained or tuned to perform multi-step reasoning tasks. "Nevertheless, the scalability of the training recipe behind current large reasoning models (LRMs) is still limited by the requirement of verifiable reward."

- Long-horizon tasks: Tasks requiring reliable performance over extended sequences of steps or time. "Existing research indicates that the reliability of single-step task execution strongly influences the duration over which a system can operate dependably, thus introspective abilities may be particularly critical for long-horizon tasks~\citep{kwa_measuring_2025}."

- Majority voting: A test-time ensembling method that selects the most common answer among multiple sampled outputs. "A common test-time scaling strategy of enhancing model capability is through majority voting."

- Multi-scale verification: A review process that examines a proof at multiple granularities, from whole-solution to fine-grained steps. "It performs multi-scale verification, ranging from the level of the complete proof down to detailed steps similar to vertical pessimistic verification."

- Natural language provers: Systems that produce and/or check proofs written in natural language rather than a formal proof language. "However, this approach would introduce notable external budget to the AI system while the performance of natural language provers can achieve 4x higher than formal provers on the same dataset~\citep{dekoninck_open_2025}."

- Pessimistic verification: A verification scheme that flags a solution as incorrect if any independent check finds an error. "In pessimistic verification we construct multiple parallel verifications for the same proof, and the proof is deemed incorrect if any one of them reports an error."

- Progressive pessimistic verification: A hierarchical variant of pessimistic verification that escalates from coarse to fine checks, pruning as errors are found. "Progressive pessimistic verification combines the mechanism of both simple and vertical methods."

- Pruning optimization: Halting or skipping further checks once a failure is detected to save computation. "Pruning optimization in this method achieves the highest runtime efficiency when negative examples are prevalent in the data distribution, while the verification cost is greatest when positive examples dominate."

- Self-evolution: A training approach where models improve using their own signals or priors without labeled data. "Another line of work focuses on leveraging the internal capability of the LLM to achieve self evolution~\citep{zuo_ttrl_2025, yu_rlpr_2025, xu_direct_2025}."

- Self-verification: Having the model evaluate or validate its own or another model’s outputs to improve reliability. "They typically rely on some form of self-verification to complete training, and we believe that such approaches have even greater potential."

- Test-time scaling: Methods that improve performance by allocating more computation at inference (e.g., more samples, longer reasoning). "A common test-time scaling strategy of enhancing model capability is through majority voting."

- Token efficiency: Performance achieved per token of compute (considering input and output token costs). "Its token efficiency even surpassed extended long-CoT in test-time scaling."

- True Negative Rate (TNR): The fraction of incorrect proofs correctly flagged as incorrect. "True Negative Rate (TNR): The proportion of detected errors among all erroneous proofs."

- True Positive Rate (TPR): The fraction of correct proofs correctly accepted as correct. "True Positive Rate (TPR): The proportion of proofs classified as correct among all truly correct proofs."

- Verifiable reward: A reward signal that can be computed reliably from explicit rules or checks, enabling reinforcement-style training. "Nevertheless, the scalability of the training recipe behind current large reasoning models (LRMs) is still limited by the requirement of verifiable reward."

- Verifier-guided workflow: A process in which a verifier’s judgments steer solution generation or refinement. "The performance IMO level math problems can be notably enhanced via a verifier-guided workflow according to \citet{huang_gemini_2025, luong_towards_2025}."

- Vertical pessimistic verification: A variant focusing on localized segments of a proof, reviewed pessimistically in parallel. "Vertical pessimistic verification adopts a hyperparameter , it first splits the whole proof into chunks with lines, and create a series of parallel review tasks for each chunk."

- Vertical review prompting: A prompting technique instructing the model to deeply analyze specific proof segments. "The vertical review prompting method used in vertical pessimistic verification and progressive pessimistic verification."

Practical Applications

Overview

Below are practical, real-world applications that emerge from the paper’s findings and workflows on pessimistic verification (simple, vertical, progressive) for open-ended mathematical proofs. Each item specifies sectors, potential tools/workflows, and key assumptions or dependencies. Applications are grouped into immediate (deployable now) and long-term (requiring further research, scaling, or development).

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be implemented with current LLMs and the paper’s verification prompts and workflows.

- Autograding of proof-based assignments and competitions

- Sectors: Education

- Tools/Workflows: LMS-integrated “progressive pessimistic verification” graders for university math courses and contest platforms (IMO/Putnam style), step segmentation via vertical PV for targeted feedback, error explanations for students

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to strong reasoning-capable LLMs; assignments formatted as stepwise proofs or solution outlines; rubric alignment to minimize undue TPR reduction; faculty oversight for edge cases

- Verifier-in-the-loop quality gate for math/code outputs

- Sectors: Software, Education, Research tools

- Tools/Workflows: Wrap existing solver models with a PV gate; deploy progressive@n/l to flag any detected error; route flagged responses to human or second-pass solver; use explanations as audit artifacts

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable error-explanation prompting; compute budget for parallel checks; calibrated thresholds to avoid excess false negatives on correct outputs

- IDE and CI/CD “PV bot” for code reviews without execution

- Sectors: Software Engineering

- Tools/Workflows: GitHub Action/GitLab CI job that applies vertical PV to code diffs (e.g., verify invariants, pre/post-conditions, algorithmic arguments); IDE plugin that highlights potentially flawed logic with step-level rationales

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Logical verification complements but does not replace runtime tests; code must include sufficient comments/specs to reason about; organizational acceptance of a stricter (pessimistic) gate

- Dataset auditing to surface mislabels and weak annotations

- Sectors: AI/ML, Research

- Tools/Workflows: Apply progressive PV to math/logic datasets to identify mislabeled positives; maintain triage queue with error rationales; improve benchmark reliability and reward functions

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of step-structured solutions; human adjudication loop for disputes; willingness to revise legacy benchmark labels

- Pre-submission proof checks and editorial triage

- Sectors: Academic Publishing (Mathematics, Theoretical CS)

- Tools/Workflows: Journal/conference triage workflows using vertical PV for section-by-section proof scrutiny; attach error explanations for authors; prioritize comprehensive checks on proofs with higher detected risk

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Strong LLM access; policy alignment on the role of automated checkers; clear rigor standards to arbitrate minor vs critical errors

- Verification for computational notebooks and technical reports

- Sectors: Research, Data Science, Energy modeling, Finance

- Tools/Workflows: PV pass that inspects derivations, assumptions, and formula transformations in notebooks, white papers, and model documentation; error explanations included for governance audits

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Documents must expose reasoning steps (not only outputs); domain-specific prompting templates; human-in-the-loop sign-off for material decisions

- Risk-model and quantitative report verification in enterprises

- Sectors: Finance, Insurance, Operations Research

- Tools/Workflows: Progressive PV of model derivations, hedging logic, optimization constraints; embed verifier gate in report-generation pipelines; store errors and rationales for audit trails

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Sufficient disclosure of modeling steps; domain adaptation of prompts; careful calibration to avoid excessive false negatives that slow throughput

- Smart contract and specification checks (logic-focused)

- Sectors: Security, Web3

- Tools/Workflows: Vertical PV on specification proofs, invariants, and formal descriptions; pre-deployment checks that flag logical gaps with error rationales

- Assumptions/Dependencies: PV focuses on logical consistency, not runtime vulnerabilities; specs must be sufficiently explicit; complementary static analysis remains necessary

- Student-facing tutoring and formative feedback

- Sectors: Education

- Tools/Workflows: Vertical PV to detect step-local errors; progressive PV to prioritize obvious issues first; generate actionable error explanations and fix suggestions

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Structured student solutions; guardrails to prevent discouragement from pessimistic flags; teacher calibration of minor vs critical errors

- Spreadsheet and business-calculation auditing

- Sectors: Daily life, SMBs, Operations

- Tools/Workflows: PV of multi-step calculations embedded in spreadsheets; error-explanation comments attached to suspect cells or formula chains

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to calculation lineage (audit trail of steps); domain prompting for finance/operations contexts; acceptance of occasional conservative flags

- Benchmark construction and automatic grading pipelines

- Sectors: AI/ML Research

- Tools/Workflows: Build math/logic benchmarks with PV-based labels and rationales; combine solver + verifier for automated scoring with more reliable error detection (higher TNR)

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Oversight for borderline cases; transparency of annotation decisions; standardization of segmentation hyperparameters (e.g., l in vertical PV)

- Reliability boost for long-horizon agent workflows

- Sectors: Robotics (symbolic planning), Software Ops

- Tools/Workflows: Insert PV checks between plan steps to detect early logical inconsistencies; prune failing branches quickly (leveraging progressive PV’s pruning benefits)

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Plans must be expressed in interpretable steps; agents tolerate conservative pruning; adequate compute for increased verification bandwidth

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, standardization, or integration into training and governance systems.

- Self-verification as a train-time signal in reasoning model pipelines

- Sectors: AI/ML

- Tools/Workflows: Integrate pessimistic verification into RL or test-time RL (e.g., TTRL) as a verifiable reward proxy; co-train solver and verifier; optimize progressive PV parameters for stable training

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust alignment of verification rationales; mitigation of TPR drops during training; compute for parallel verification; empirical studies on generalization across domains

- Autonomous theorem-proving agents for research-level mathematics

- Sectors: Academia (Mathematics), Theoretical CS

- Tools/Workflows: Triadic systems (pose–solve–verify) where pessimistic verification steers exploration; escalate flagged segments to formal provers (Lean/Isabelle) for formalization

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Strong frontier LLMs; hybrid pipelines bridging natural-language proofs to formal proof assistants; long-horizon orchestration and provenance tracking

- Regulatory and compliance standards for AI-produced quantitative reasoning

- Sectors: Policy, Finance, Healthcare, Energy

- Tools/Workflows: Mandate verifier-in-the-loop with pessimistic gating for AI-generated calculations in high-stakes contexts; require error explanations and audit logs; establish sector-specific rigor thresholds

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Standardized metrics (TPR/TNR/Balanced F1) for verification systems; certification processes; privacy/security controls on sensitive data

- Enterprise-grade verification platforms with multi-solver orchestration

- Sectors: Software, Finance, Energy, Operations

- Tools/Workflows: “Pessimistic orchestration” that selects solutions with least detected uncertainty across multiple solver models; scalable verification services with progressive pruning for cost control

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Model diversity for solver ensembles; cost-aware routing; monitoring of calibration drift; robust fallback paths

- Hybrid verification pipelines combining PV with formal methods

- Sectors: Software Verification, Safety-Critical Systems, Security

- Tools/Workflows: Use PV to triage and localize suspect segments; hand off to formal provers or symbolic execution; maintain linked rationales across natural and formal artifacts

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Interoperability between natural-language steps and formal specifications; tooling for translation/annotation; domain expertise for adjudication

- Standardized educational assessment with step-level verification rubrics

- Sectors: Education (K–12, Higher Ed)

- Tools/Workflows: Curriculum and exam design that require step-exposed solutions; PV-backed automated assessment; large-scale deployment with calibrated strictness and formative feedback loops

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Consensus on error categories (critical vs minor); governance to prevent over-penalization; teacher training and acceptance

- Reliability extensions for long-horizon autonomy

- Sectors: Robotics, Autonomous Software Agents

- Tools/Workflows: Embed progressive PV to increase time-horizon reliability (error detection correlates with longer dependable operation); standard APIs for plan verification and pruning

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Stable introspective capabilities across tasks; error-explanation fidelity; empirical validation in real-world environments

- Document and model audit systems at organizational scale

- Sectors: Enterprises, Government

- Tools/Workflows: PV-based auditors for optimization models, scheduling plans, and policy memos; dashboards with error rationales and remediation workflows; archival of verification artifacts

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Structured documentation practices; integration with existing governance/risk platforms; human adjudication capacity for contested findings

Notes on Feasibility and Dependencies

- Model strength and prompting quality: Many applications assume access to reasoning-capable LLMs and well-crafted PV prompts (especially for error explanations).

- Step-structured artifacts: PV is most effective when solutions are segmented (vertical PV), or proofs are delineated into clear steps for multi-scale review.

- Calibration trade-offs: Pessimistic gating raises TNR (error detection) and may lower TPR; thresholds and reviewer policies must be tuned per domain to avoid excessive rejection of correct outputs.

- Compute and cost: Progressive PV’s parallel checks are more token-efficient than long CoT and often faster, but still require budget planning and pruning strategies for scale.

- Human-in-the-loop: For high-stakes decisions and ambiguous cases (minor vs critical errors), human review remains essential; PV’s rationales enable efficient triage.

- Domain adaptation: Sector-specific templates and rigor standards improve reliability; hybridization with formal tools enhances correctness in safety-critical contexts.

- Data quality: As the case paper suggests, PV can expose annotation errors; governance processes must support dataset relabeling and benchmark improvement.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.