Scaling Generative Verifiers For Natural Language Mathematical Proof Verification And Selection (2511.13027v1)

Abstract: LLMs have achieved remarkable success on final-answer mathematical problems, largely due to the ease of applying reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards. However, the reasoning underlying these solutions is often flawed. Advancing to rigorous proof-based mathematics requires reliable proof verification capabilities. We begin by analyzing multiple evaluation setups and show that focusing on a single benchmark can lead to brittle or misleading conclusions. To address this, we evaluate both proof-based and final-answer reasoning to obtain a more reliable measure of model performance. We then scale two major generative verification methods (GenSelect and LLM-as-a-Judge) to millions of tokens and identify their combination as the most effective framework for solution verification and selection. We further show that the choice of prompt for LLM-as-a-Judge significantly affects the model's performance, but reinforcement learning can reduce this sensitivity. However, despite improving proof-level metrics, reinforcement learning does not enhance final-answer precision, indicating that current models often reward stylistic or procedural correctness rather than mathematical validity. Our results establish practical guidelines for designing and evaluating scalable proof-verification and selection systems.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Scaling Generative Verifiers for Checking Math Proofs: A Simple Guide

Overview

This paper looks at how AI LLMs can check and choose correct math proofs written in natural language, not just spit out right final answers. The main idea is: getting the final number right is easy to check, but making sure the reasoning (the proof) is truly correct is much harder. The authors test and improve two ways to “judge” proofs and show that combining them works best at scale. They also warn that some common ways of testing can give misleading results.

What questions does the paper try to answer?

Here are the big questions the researchers ask (in simple terms):

- How can we reliably tell if a written math proof is correct?

- If there are many different proofs for the same problem, how do we choose the best one?

- Does the wording of the instructions we give to the judge AI (the “prompt”) change how well it judges?

- Can training (reinforcement learning) make the judge AI more reliable?

- What kind of tests and datasets give fair, trustworthy measurements of judge quality?

How did they paper the problem?

They compare two main approaches, using everyday analogies:

- LLM-as-a-Judge (like a referee):

- An AI reads one proof and gives a score or a yes/no verdict: “correct” or “incorrect.”

- To be more confident, they ask the judge multiple times (like getting several referees) and combine the votes.

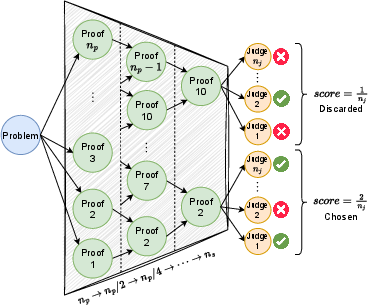

- GenSelect (like a tournament):

- The AI compares two proofs at a time and picks the better one.

- By running many matchups (pairwise comparisons), a “winner” proof emerges.

- There are two tournament styles:

- Knockout: losers are removed quickly; cheap but less accurate.

- Full pairwise: every pair plays; more accurate but much more expensive.

They also:

- Scale up compute: generate many candidate proofs (like 128–512) and use systematic judging to pick the best.

- Try different judging prompts (instructions) to see how much wording matters.

- Use reinforcement learning (RL) to train the judge AI to match human labels, aiming to make it less sensitive to prompt wording.

- Evaluate using multiple datasets and both proof-level correctness and final-answer correctness, because a “pretty-looking” proof isn’t always mathematically valid.

Helpful terms:

- Precision: Of all proofs judged “correct,” how many are truly correct? (Avoids false praise.)

- Recall: Of all truly correct proofs, how many did the judge recognize? (Avoids missing good proofs.)

- Final-answer vs proof-level: Final-answer checks if the last number/statement is right; proof-level checks the logic throughout.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

Here are the main takeaways the authors highlight:

- Testing can be misleading if datasets are imbalanced or noisy.

- Example: A simple, non-smart trick (like “if the problem mentions triangles, say ‘incorrect’”) can score surprisingly well because of hidden patterns in the data.

- Some models format proofs with “-----”, and that accidentally correlates with correctness, fooling simple judges.

- Prompt wording matters a lot for judgment quality.

- Different prompts emphasize style vs strict correctness.

- Some prompts give high recall (catch many correct proofs) but low precision (also mark wrong proofs as correct).

- Others do the opposite.

- Reinforcement learning helps—but not in the most important way.

- RL improves proof-level metrics and reduces sensitivity to prompt wording.

- However, it doesn’t improve final-answer precision much.

- This suggests judges are getting better at spotting style issues (like missing justifications) rather than genuinely understanding math logic.

- Step-by-step judging (splitting the proof into steps and judging each) increases precision but drops recall and overall accuracy. Being too strict causes many “false negatives.”

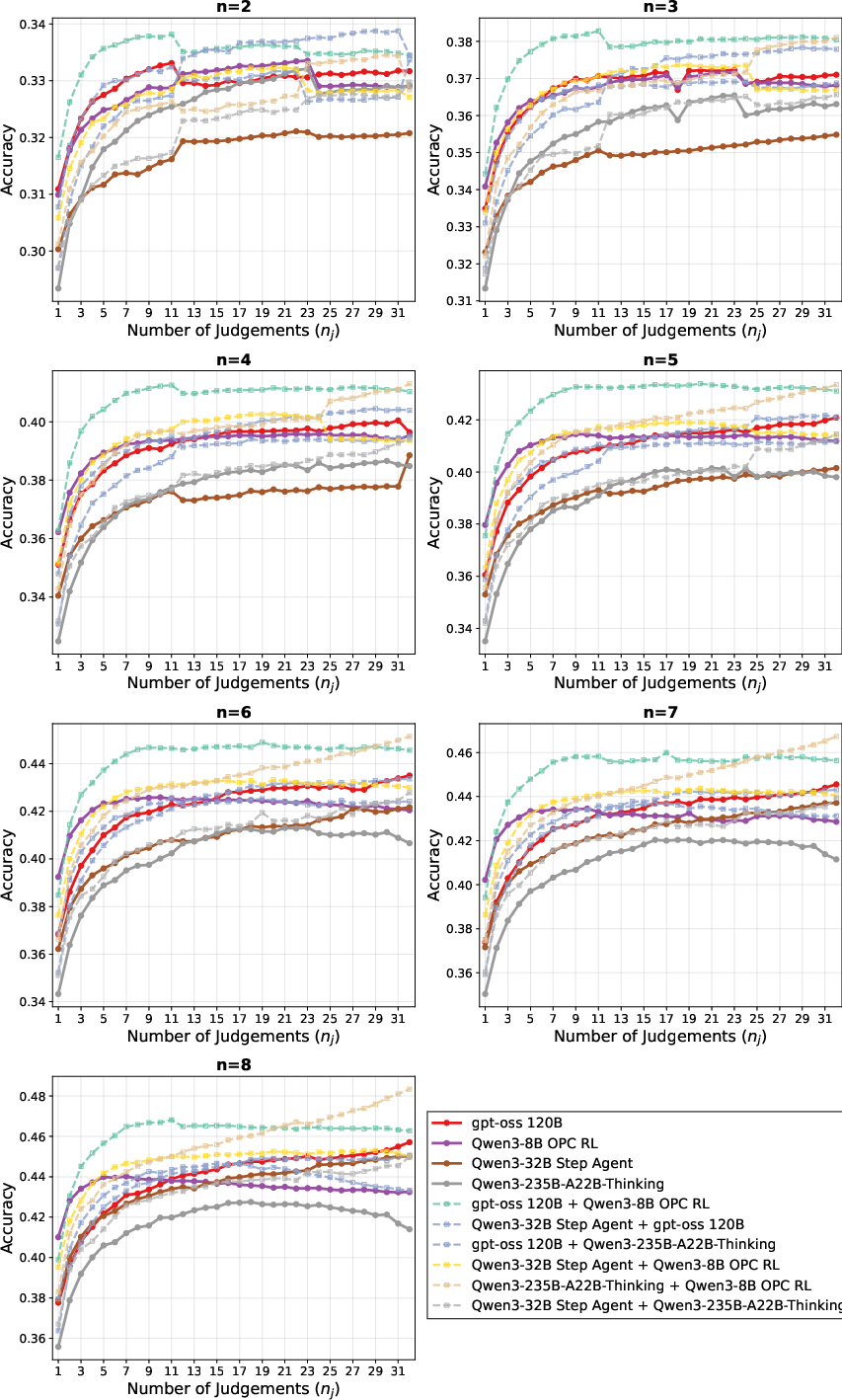

- Ensembling (averaging multiple judges) usually doesn’t beat the best single judge.

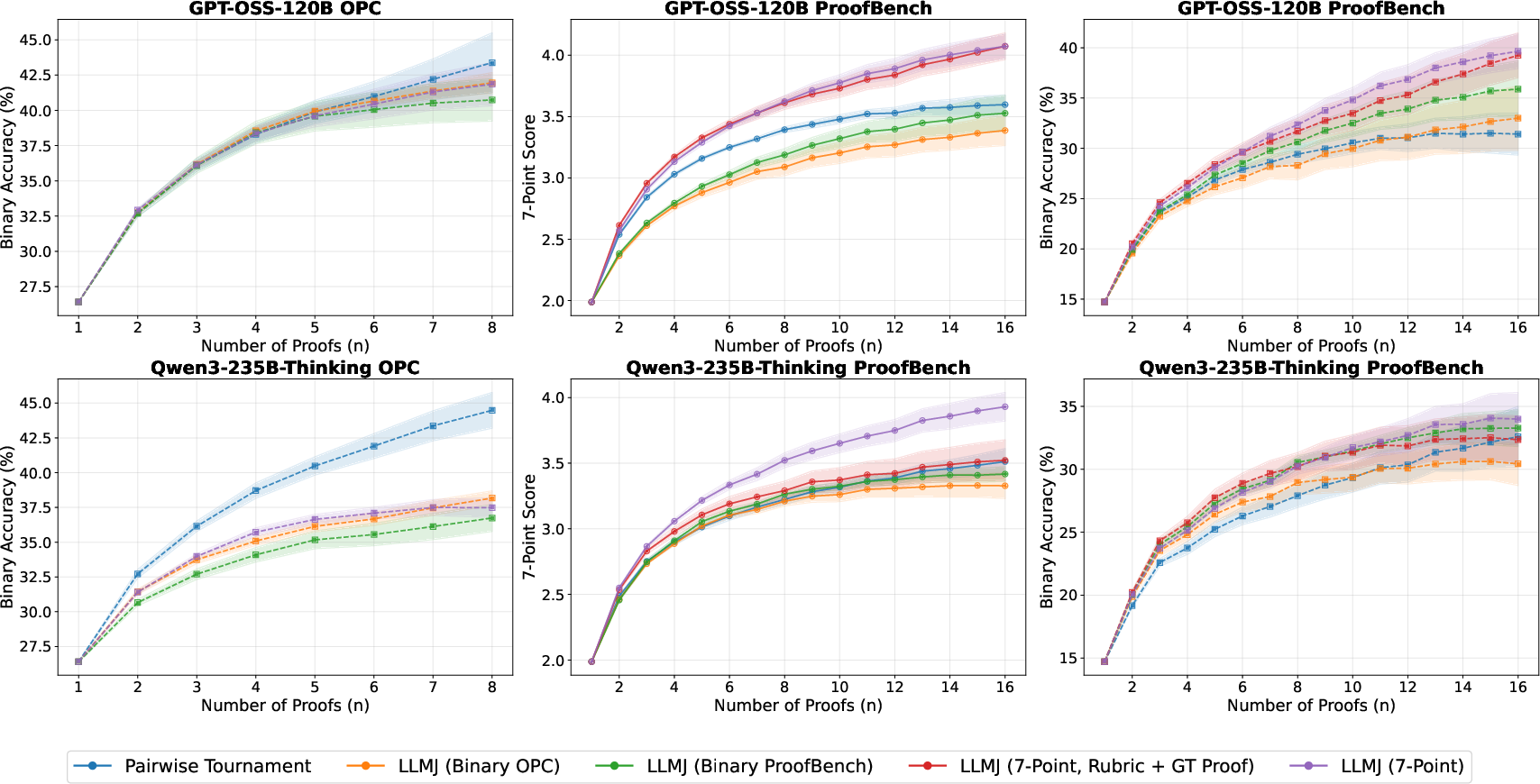

- 7-point scoring (grading proofs like in contests) doesn’t consistently beat simple yes/no judging for picking the best proof; which is better depends on the dataset.

- A hybrid, scalable selection method works best:

- First, run a quick knockout tournament (GenSelect) to narrow down to a small set of strong proofs.

- Then, use LLM-as-a-Judge to score those finalists and pick the best.

- This approach balances accuracy and cost better than using only one method.

- It achieved very strong results on tough final-answer benchmarks (e.g., 100% on AIME 2025 with their setup).

- Even strong LLMs can be overconfident judges on hard problems.

- They sometimes mark clearly incorrect proofs as correct.

- Human checking is still needed on high-stakes, difficult problems.

Why are these results important?

- Proof checking is essential for advancing from high-school-level problems (where final answers are easy to verify) to competition-level and research-style math (where logical rigor matters).

- The paper gives practical advice for building reliable proof judging systems:

- Use diverse, balanced datasets to avoid hidden shortcuts and biases.

- Measure both proof-level and final-answer performance, so judges aren’t fooled by style.

- Combine GenSelect and LLM-as-a-Judge for better accuracy and manageable compute cost.

- Use RL to make judges less dependent on prompt wording—but don’t expect it to magically fix deep math understanding.

What’s the impact and what comes next?

- Implications:

- Don’t trust a single benchmark. Use multiple tests and balanced datasets.

- Be careful: some high scores may come from spotting style patterns, not real math understanding.

- For now, humans should still verify proofs when accuracy is critical.

- Future directions:

- Build better, tougher benchmarks with reliable human labels focused on hard proofs.

- Scale RL training and data—especially with challenging, diverse proofs—to push judges toward true mathematical reasoning.

- Explore improved step-level judging and better ways to combine step decisions.

- Continue refining the hybrid selection approach to pick the best proof among many candidates efficiently.

In short, the paper shows how to scale and improve AI proof judges, warns about common pitfalls in evaluation, and offers a practical, hybrid method that performs well today—while highlighting that genuine mathematical understanding remains an open challenge.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a concise, actionable list of knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that remain unresolved in the paper. These items focus on what is missing, uncertain, or left unexplored so future researchers can build on them.

- Constructing large, high-quality, low-noise proof-judgment datasets: how to reliably scale human grading, reconcile disagreements, and provide robust ground truth beyond VerOPC’s noise ceiling and VerProofBench’s small size.

- Eliminating spurious correlations and style artifacts in datasets (e.g., geometry bias, “-----” separators): systematic procedures for adversarial data cleaning and bias audits to prevent trivial heuristics from inflating judge accuracy.

- Cross-model and cross-problem distribution balance: how to curate benchmarks that remain robust when generator models, problem domains, and difficulty shift, and avoid any single model/style dominating “correct” proofs.

- Final-answer vs proof-level alignment: why RL improves proof-level metrics yet fails to raise final-answer precision; what training signals explicitly target mathematical validity rather than stylistic/procedural cues.

- Reliable step-level supervision: scalable creation of step-level labels and methods for step decomposition; principled aggregation rules beyond “all steps must be correct” to reduce false negatives while preserving rigor.

- Prompt robustness at scale: strategies to learn or optimize prompts automatically (via RL or meta-learning) to reduce sensitivity without overfitting to specific datasets or artifacts.

- Rubric usage policy: when and how providing rubrics or ground-truth solutions helps or harms judge reliability; methods to generate trustworthy rubrics automatically; safeguards against rubric leakage and overfitting.

- Judge calibration and uncertainty: formal measures (ECE, selective prediction, abstention policies) and training techniques to reduce false positives under low base-rate conditions where correct proofs are rare.

- Ensemble design for judges: diversity-aware ensembling, stacking, or meta-judges that outperform the best single judge, and criteria for selecting complementary judges without relying on in-distribution advantages.

- Formal verification integration: pipelines to translate natural-language proofs into formal representations and combine LLM judges with theorem provers to reduce reliance on style and increase mathematical soundness.

- Theoretical analysis of selection methods: characterize conditions under which GenSelect (knockout vs pairwise) or LLM-as-a-Judge is superior; derive compute–accuracy trade-offs and sample complexity bounds for tournaments.

- Adaptive compute allocation: algorithms to dynamically choose n_p (proofs), n_s (selected subset), and n_j (judgements) per problem based on difficulty estimates or judge uncertainty to optimize token budgets.

- Stress-testing judges under rare-correct regimes: controlled evaluations where correct proofs are extremely scarce to quantify false positive rates and robustness, including adversarially perturbed styles and proofs.

- Mechanistic audits of judge behavior: methods to identify which features (stylistic markers vs mathematical content) judges rely on; experiments with style obfuscation to measure true content sensitivity.

- Cross-dataset generalization: standardized protocols to measure judge transfer across VerOPC, VerProofArena, SelOPC, SelProofBench, and new unseen distributions without performance collapse.

- Scaling RL for judges: effects of larger, cleaner training sets, longer training horizons, and alternative objectives (pairwise ranking, margin-based rewards, process-level rewards) on true mathematical validity.

- Joint training of solvers with judges: safe RLVR pipelines for proof generation where judge biases do not distort optimization; techniques to prevent propagation of judge errors into solver training.

- Step-based judgment improvements: learning better step segmentation, weighting steps by dependency/criticality, and employing probabilistic aggregation or structured reasoning graphs to balance precision and recall.

- Long-context constraints: evaluating and improving judge performance on very long proofs (>10K tokens) without filtering, via long-context models, retrieval mechanisms, or hierarchical judging strategies.

- Benchmark scaling and significance: building larger best-of-n selection datasets (beyond 29 problems) and employing statistical testing to avoid conclusions driven by one-problem differences and high variance.

- Metrics that reflect high-stakes reliability: beyond accuracy/F1, include PR curves, false discovery rate, selective accuracy under abstention, and cost-sensitive objectives tuned to low base-rate settings.

- Generator–verifier decoupling: ensuring judge reliability even when the solver is stronger than the judge (or vice versa); protocols for evaluating judges against generators with unseen styles and higher capability.

Glossary

- Binomial coefficient: The combinatorial count of unordered pairs; used to denote how many pairwise comparisons are required. "Alternatively, a pairwise tournament compares all pairs and selects the proof winning the most comparisons."

- DAPO algorithm: A reinforcement learning algorithm for optimizing LLMs via direct alignment of preferences/policies. "We train Qwen3-30B-A3B-Thinking-2507 and Qwen3-8B using the DAPO algorithm~\citep{yu2025dapo} on the VerOPC~\citep{dekoninck2025open} training set."

- Final-answer precision: The proportion of judged-correct solutions whose final numeric answer is actually correct. "However, despite improving proof-level metrics, reinforcement learning does not enhance final-answer precision, indicating that current models often reward stylistic or procedural correctness rather than mathematical validity."

- GenSelect: A generative verification method where the model compares candidate proofs in-context to select the best one. "GenSelect~\citep{toshniwal2025genselect,dekoninck2025open} takes a comparative approach: rather than evaluating proofs individually, the model compares many proofs in-context, and selects the best one."

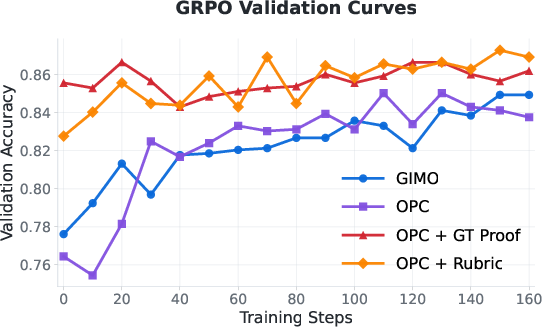

- Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO): A policy-gradient RL algorithm that optimizes generation by comparing outputs within a group against relative rewards. "We use the OPC training set to train a Qwen3-30B-A3B-Thinking-2507 model using Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) \citep{shao2024deepseekmath} with a binary reward, measuring whether the model judgement matches the ground truth judgement."

- In-distribution: Data whose distribution matches the training distribution, often yielding more favorable performance. "In contrast, the VerOPC (in-distribution) dataset has higher correct proofs and easier problems."

- Knockout tournament: A single-elimination comparison scheme that selects a winner using minimal pairwise matches. "A knockout tournament operates in single-elimination format, requiring exactly comparisons to select a winner from candidates."

- LLM-as-a-Judge: A paradigm where an LLM evaluates the correctness/quality of a proof, producing binary or graded judgments. "In the LLM-as-a-Judge paradigm~\citep{whitehouse2025j1,zhang2024generative,shi2025heimdall}, a LLM directly evaluates the correctness of a single proof, typically producing either a binary judgement or a fine-grained score (e.g., on a 7-point scale)."

- Majority@5: An evaluation protocol that aggregates five independent judgments per item and takes the majority decision. "Figure \ref{fig:rl_fig} (right) reports majority@5 results on both proof-level and final-answer judgements."

- Noise ceiling: The upper bound on reliable performance imposed by label noise in the dataset. "the VerOPC test set is not suitable for evaluating strong proof graders, as the noise ceiling is too low."

- Out-of-distribution: Data drawn from a distribution different from training, often harder and less reliable for models. "The VerProofArena (out-of-distribution) dataset is more challenging, with correct proofs being scarce, having lower label noise, and correct proofs being generated by stronger models."

- Pairwise tournament: A selection method that compares every pair of candidates and chooses the one with the most wins. "Alternatively, a pairwise tournament compares all pairs and selects the proof winning the most comparisons."

- Pass@n: A sampling-based metric indicating the probability that at least one of n generated candidates solves the problem. "SelOPC: The pass@n subset from the OPC~\citep{dekoninck2025open} dataset consisting of 60 problems with 8 proofs per problem generated by the OpenAI o4-mini model."

- Policy-gradient reinforcement learning: RL methods that update model parameters using gradients of expected rewards under a policy. "Verification: Given a single proof, determine its correctness, enabling precise reward signals for policy-gradient reinforcement learning approaches such as GRPO~\citep{shao2024deepseekmath}."

- Reward models: Learned models that score outputs to provide training signals for tasks with hard-to-verify objectives. "Recent works have explored training reward models to tackle hard-to-verify tasks."

- Rubric: A structured grading guideline or reference solution used to assess proofs more systematically. "Overall, adding the rubric does not lead to a substantial performance gain in proof judgement, except for improvement in final-answer precision (see Figure~\ref{fig:rl_fig} Right)."

- Self-critique: A method where a model generates and then critiques its own responses according to a specified rubric. "Kimi K2~\citep{team2025kimi} use a self-critique-based approach to generate responses and act as its own critique to judge the response given a predefined rubric for the task."

- Sequential depth: The number of dependent stages required in a process, limiting parallelization efficiency. "While this approach is token-efficient, it has a sequential depth of at least , limiting parallelization."

- Spurious correlations: Non-causal statistical patterns that models may exploit to appear accurate without true understanding. "Model and problem imbalances in the dataset may lead models to exploit spurious correlations to achieve high accuracy without genuinely understanding the mathematical content of proofs."

- Step-based judgement: A verification strategy that decomposes proofs into steps, judges each step, and aggregates to a final verdict. "We implement a step-based judgement model with two prompts: (1) the model decomposes the proof into steps, and (2) the model is reprompted with each step highlighted and asked to judge whether the step is correct."

- Temperature sampling: A stochastic generation technique that controls randomness via a temperature parameter. "Given a problem, we first generate candidate proofs by temperature sampling from a LLM."

- Test-time compute scaling: Increasing computational resources at inference (e.g., more samples or longer reasoning) to improve performance. "Prior research has demonstrated that test-time compute scaling substantially improves performance on mathematical reasoning tasks."

- Top-k: A decoding constraint that limits sampling to the k most likely tokens at each step. "for Qwen models, we sample with temperature $0.6$, top-p $0.95$ and top-k $20$."

- Top-p: Nucleus sampling that restricts choices to the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability exceeds p. "For GPT-OSS models, we sample with temperature $1.0$ and top-p $1.0$"

- Verifiable rewards (RLVR): Reinforcement learning setups where correctness can be automatically checked to yield reliable reward signals. "well-suited for reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (RLVR)~\citep{shao2024deepseekmath}, enabling steady improvements in model performance."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now using the paper’s methods, evaluation guidelines, and open-source recipes.

- Proof selection at scale with hybrid verification (software, education, research)

- Deploy the hybrid workflow that combines GenSelect knockout tournaments with LLM-as-a-Judge scoring to select the best proof or solution from many candidates at lower compute than pure judging.

- Tools/products/workflows: integrate the NeMo Skills recipe (GitHub link in paper) to orchestrate n_p candidate generation, n_s knockout selection, and n_j parallel judgments; expose a “proof-select” microservice.

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to high-capacity LLMs (e.g., GPT-OSS-120B, Qwen3-235B), long-context inference, and GPU resources; domain remains in natural-language proofs; human-in-the-loop for high-stakes reviews.

- Quality gating in math reasoning pipelines (software, education)

- Use the judge to filter out low-quality or stylistically flawed proofs before surfacing outputs to users or downstream systems (e.g., tutors, homework assistants, challenge problem solvers).

- Tools/products/workflows: a gating step that scores candidate solutions via OPC-style prompt; route uncertain or borderline cases to human review.

- Assumptions/dependencies: calibration-focused gains are larger than gains in true mathematical validity; rely on precision monitoring rather than accuracy alone.

- Dataset curation and hygiene protocols (academia, industry MLOps)

- Apply the paper’s multi-faceted evaluation and balance criteria to build cleaner training sets: avoid model- or topic-imbalances (e.g., geometry bias), mix correct/incorrect outputs from all generators, and monitor precision on balanced final-answer sets.

- Tools/products/workflows: internal “judgment precision dashboard,” bias audits (e.g., keyword scans for unintended correlations), and validation sets with equal correct/incorrect ratios.

- Assumptions/dependencies: availability of diverse generators, grading capacity to produce high-quality labels, and willingness to discard flawed or biased data sources.

- RL fine-tuning to reduce prompt sensitivity of judges (software, academia)

- Use RL (e.g., GRPO/DAPO) on judge models to stabilize performance across prompts and modestly improve proof-level metrics, while recognizing it won’t materially improve final-answer precision without better data.

- Tools/products/workflows: train Qwen3-30B-class judge models on VerOPC training data; deploy prompt-agnostic “Judge-RL” checkpoints.

- Assumptions/dependencies: sufficient labeled judgments for RL; judge trained on in-distribution data generalizes acceptably; careful monitoring for overfitting to stylistic cues.

- Compute-aware inference orchestration (software, cloud)

- Implement test-time compute scaling policies that trade off accuracy and cost: use knockout tournaments first (cheap), then apply a limited number of parallel judgments to the top candidates (accurate).

- Tools/products/workflows: inference schedulers that set n_p, n_s, n_j dynamically based on budget and target accuracy; “auto-tune” compute knobs per task difficulty.

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust cost tracking; standardized prompt templates; model parallelism available to exploit high concurrency for judgments.

- Triage graders for math competitions and coursework (education)

- Use judges to pre-score proofs on a binary or 7-point rubric, primarily to flag missing justifications and style issues, before sending to expert graders for rigorous correctness checks.

- Tools/products/workflows: “first-pass grader” for USAMO/IMO-like problems; batch judgments with majority@k and rubric injection only for final-answer verification when possible.

- Assumptions/dependencies: contested or rare-correct cases are escalated; teachers/graders retain final authority; transparency about known limitations and false positives.

- Precision-first QA in production (software, finance modeling support)

- Track precision (likelihood a “correct” judgment actually has the correct final answer) on a balanced final-answer set to detect judges exploiting superficial features; gate deployment on precision thresholds.

- Tools/products/workflows: precision alerts and regression tests; QA harness that isolates stylistic confounds; require “rubric-based” verification for numeric-answer tasks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: availability of balanced evaluation sets; adoption of precision as the primary KPI instead of only accuracy/recall.

- Guardrail templates and rubric injection policies (software, daily life learning apps)

- Use rubric injection to boost precision for final-answer problems and to better enforce structure in output proofs; deploy standardized OPC-style prompts with optional rubric fields.

- Tools/products/workflows: prompt libraries with toggles for rubric/ground-truth inclusion; simple numeric rubric for final-answer problems; guidance that rubrics do not guarantee better proof-level performance in OOD settings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: rubrics must be correct; avoid leakage or bias; measure whether rubric help is task-specific (numeric answers vs full proofs).

Long-Term Applications

These applications require improved datasets, stronger models, step-level methods, or scaling of RL and verification strategies before widespread deployment.

- Reliable autonomous mathematical judges (software, academia)

- Build judges that robustly assess deep mathematical validity (not just style), especially when correct proofs are rare and errors are subtle.

- Tools/products/workflows: large-scale high-quality proof datasets, multi-step decomposition with better aggregation, adversarial benchmarks to probe logical rigor, stronger RL with process-level rewards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: curated OOD benchmarks; improved step-level supervision; model architectures that understand formal logic structure.

- Reward-model-driven proof generation (software, academia)

- Use generative verifiers as reward models to train solvers via RLVR for proof tasks, tying rewards to verified logical steps rather than final answers.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Proof-RM” models that score steps or subclaims; GRPO/DAPO training loops tuned for proofs; closed-loop generation-refinement with judges.

- Assumptions/dependencies: scalable, low-noise step labels; verifiers that generalize beyond stylistic cues; efficient long-context training regimes.

- Natural-language to formal proof pipelines (software, formal methods)

- Combine hybrid selection with step-level verification to choose the most promising NL proof and guide automated translation into systems like Lean/Isabelle/Coq.

- Tools/products/workflows: “ProofBridge” that selects NL candidates, segments into steps, and compiles into formal proof scripts with iterative checking and correction.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable step segmentation; alignment between NL claims and formal proof primitives; access to formal theorem libraries and compilers.

- Cross-domain generative verification for high-stakes reasoning (policy, healthcare, finance, legal)

- Adapt hybrid GenSelect + LLM-as-a-Judge to verify safety cases, clinical protocols, risk models, and legal arguments, with domain-specific rubrics and step validation.

- Tools/products/workflows: sector-specific “Verifier Kits” with structured rubrics, domain ontologies, and escalation workflows; regulators may mandate precision and human oversight thresholds.

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain-expert-labeled datasets; liability-aware deployment; strict governance for human-in-the-loop and traceability.

- Scalable benchmark and evaluation governance (academia, policy)

- Institutionalize multi-faceted evaluation: balanced final-answer datasets, bias audits, precision-first metrics, and adversarial stress tests to certify judges and solvers.

- Tools/products/workflows: open benchmark consortia; certification protocols for math judges; data sheets detailing imbalance and label-noise ceilings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: sustained community effort; shared standards; funding for ongoing dataset maintenance and auditing.

- Step-level judgment that actually improves correctness (software, academia)

- Develop better step decomposition and aggregation methods (e.g., probabilistic or structured models) that increase recall without collapsing precision, enabling robust end-to-end verification.

- Tools/products/workflows: structured chain-of-thought validators; graph-based proof checkers; hierarchical reward shaping for RL.

- Assumptions/dependencies: new prompts, models, and algorithms for step aggregation; rich supervision; efficient long-context reasoning.

- Adaptive compute allocation and uncertainty quantification (software, cloud)

- Build systems that dynamically choose n_p, n_s, and n_j based on problem difficulty and judged uncertainty, integrating Bayesian or conformal techniques to bound risk.

- Tools/products/workflows: “compute controllers” that adjust tournament depth and judgment count; uncertainty scores that trigger human review or additional sampling.

- Assumptions/dependencies: uncertainty estimation calibrated to OOD conditions; cost-aware orchestration; reliable difficulty estimators.

- Educational proof authoring assistants with rigorous feedback (education, daily life)

- Create assistants that coach students through proofs, identifying missing justifications and circular reasoning, and providing step-level feedback aligned to rubrics.

- Tools/products/workflows: classroom LMS integrations; teacher dashboards with triage summaries; homework apps with iterative proof refinement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: improved correctness judgment (beyond style); curated curricula and rubrics; robust privacy and fairness safeguards.

Common Assumptions and Dependencies

- Strong LLMs with long-context capabilities and access to GPUs/accelerators; licensing for commercial deployment.

- High-quality, balanced datasets with reliable labels; adversarial and OOD evaluation sets to avoid exploiting spurious correlations.

- Human-in-the-loop processes for high-stakes contexts; clear escalation and accountability.

- Precision-first monitoring to detect over-reliance on stylistic features; acceptance that current gains are largely calibration rather than deep validity.

- Cost-aware inference orchestration and model parallelization; robust logging of prompts, judgments, and decisions.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.