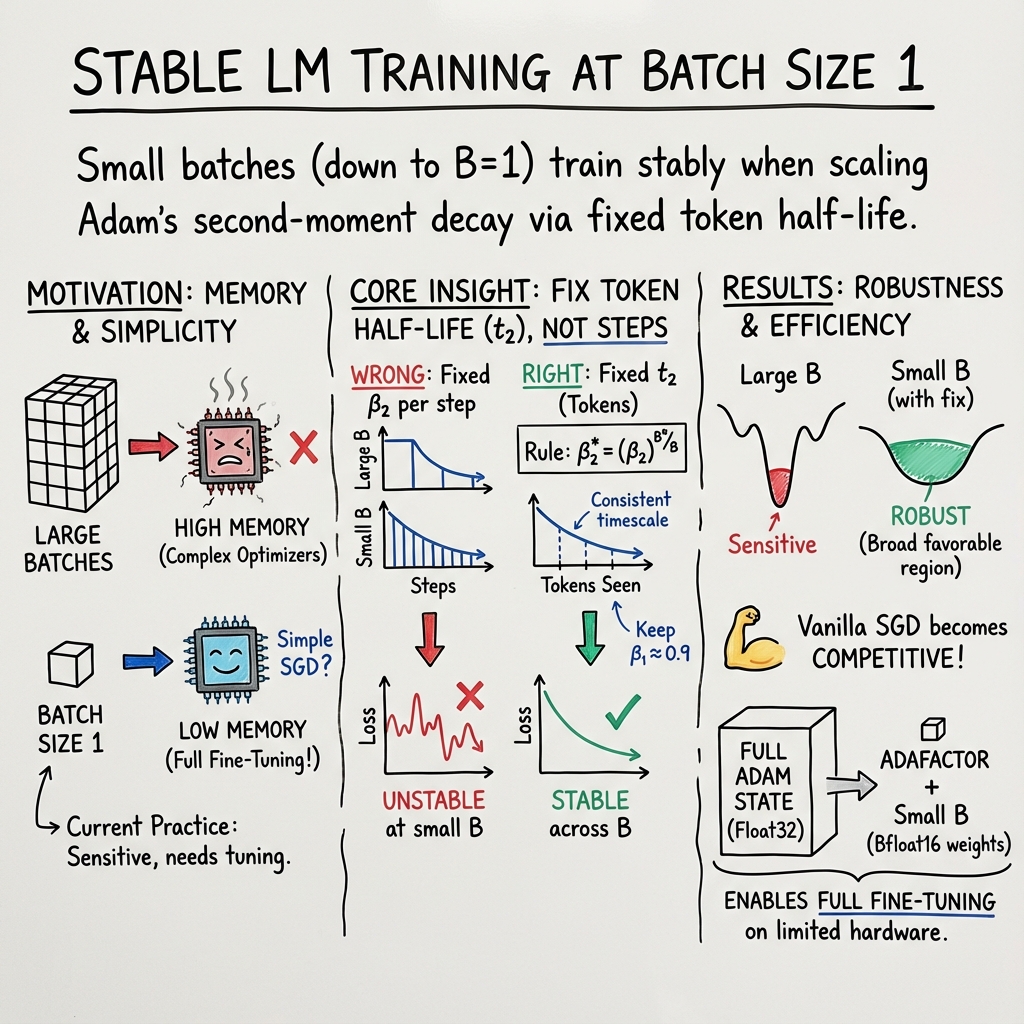

- The paper challenges the need for large batch sizes by showing that tiny batches with vanilla SGD maintain stability and efficiency.

- It demonstrates that proper hyperparameter scaling, especially for Adam’s β₂, stabilizes training with small batch sizes.

- Empirical results reveal that small batches are robust to hyperparameter misspecification and can achieve competitive per-FLOP performance.

Small Batch Size Training for LLMs

Introduction

The prevalent preference for large batch sizes in LLM training is often justified with arguments centered around stability and efficiency, which consequently necessitate the use of sophisticated optimizers. "Small Batch Size Training for LLMs: When Vanilla SGD Works, and Why Gradient Accumulation Is Wasteful" challenges this conventional belief, proposing that small batch sizes may indeed be advantageous. The authors provide both theoretical insights and empirical evidence to support the use of small batch sizes, even down to a single batch, by demonstrating stability, robustness, and competitive performance with simpler optimizers like vanilla SGD.

Revisiting Batch Size Norms

The paper sets out to debunk the notion that smaller batch sizes are inherently unstable and less efficient. It challenges the common practice of gradient accumulation, which increases the effective batch size at the cost of more optimizer steps. Their findings suggest that when certain hyperparameter scaling rules, especially for Adam's β2, are properly applied, the training of LLMs with small batch sizes is not only feasible but can be preferable. The study emphasizes adjusting the half-life of the second moment rather than the decay rate β2 across batch sizes to stabilize training (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Fixing the half-life of the second moment estimate in terms of tokens t2 scales better than fixing β2.

This approach mitigates typical instability observed with smaller batch sizes and can lead to superior per-FLOP performance, contrary to the expectation that larger batches necessarily offer better compute efficiency.

Empirical Findings

The empirical results from training various LLMs, including models like GPT-2 and GPT-3, reveal several critical insights. Notably, in the small batch regime, optimizers such as vanilla SGD without momentum become competitive with more intricate algorithms like Adam, suggesting that simpler methods may suffice when the batch-related hyperparameters are optimally configured. Furthermore, the authors find that smaller batch sizes are robust against hyperparameter misspecification, offering significant practical benefits in reducing the need for extensive hyperparameter tuning (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Small batch sizes are robust to hyperparameter misspecification.

The robustness of small batch sizes, as shown in the study, underscores their practical value, particularly when considering the reduced cost and complexity in tuning optimizer settings.

Theoretical Implications

From a theoretical perspective, the paper provides insights into the dynamics of optimization when employing small batch sizes. It contends that large steps, which are typically required in large batch training due to fewer steps per token, necessitate sophisticated optimization strategies. In contrast, smaller batch sizes taking more frequent, smaller steps avoid difficulties evolved from predicting the optimization landscape far from the current trajectory. This observation aligns with the broader tendency of small batch training to focus on localized, precise navigations in the parameter space.

Practical Recommendations

One of the practical recommendations arising from this research is favoring the smallest batch size that ensures maximal model throughput, measured in tokens per second, effectively optimizing the model's FLOPs utilization. The inefficiencies of gradient accumulation are highlighted, with advice against its use barring specific scenarios involving multiple devices. The study encourages practitioners, especially those constrained by memory, to leverage small batch sizes in conjunction with simpler, memory-efficient optimizers like Adafactor during fine-tuning (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Vanilla SGD performs competitively at larger model scales with minimal tuning.

Conclusion

This paper advocates a paradigm shift in approaching batch size determination and optimizer choice for training LLMs. It challenges entrenched notions that large batch sizes and complex optimizers are indispensable for efficient and stable training. The findings support a reevaluation of training practices, suggesting that small batch sizes paired with carefully scaled hyperparameters and simpler optimization algorithms could enhance both training efficiency and ease of hyperparameter management. Future work could extend these findings to further refine optimizer design specifically tailored to the small batch regime.