Seesaw: Accelerating Training by Balancing Learning Rate and Batch Size Scheduling (2510.14717v1)

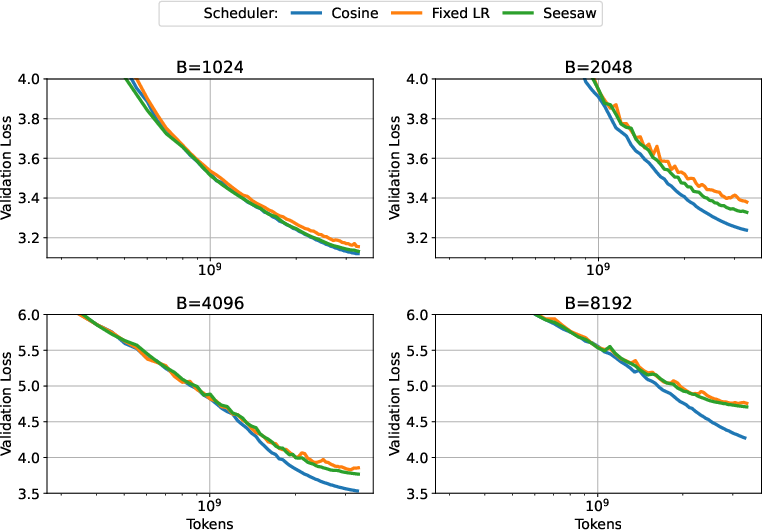

Abstract: Increasing the batch size during training -- a ''batch ramp'' -- is a promising strategy to accelerate LLM pretraining. While for SGD, doubling the batch size can be equivalent to halving the learning rate, the optimal strategy for adaptive optimizers like Adam is less clear. As a result, any batch-ramp scheduling, if used at all, is typically tuned heuristically. This work develops a principled framework for batch-size scheduling and introduces Seesaw: whenever a standard scheduler would halve the learning rate, Seesaw instead multiplies it by $1/\sqrt{2}$ and doubles the batch size, preserving loss dynamics while reducing serial steps. Theoretically, we provide, to our knowledge, the first finite-sample proof of equivalence between learning-rate decay and batch-size ramp-up for SGD on noisy linear regression, and we extend this equivalence to normalized SGD, a tractable proxy for Adam, under a variance-dominated regime observed in practice. Empirically, on 150M/300M/600M-parameter models trained at Chinchilla scale using a constant (critical) batch size, Seesaw matches cosine decay at equal FLOPs while reducing wall-clock time by $\approx 36\%$, approaching the theoretical limit implied by our analysis.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces a simple way to speed up training LLMs without hurting their final performance. The idea is called “Seesaw.” It balances two knobs you can turn during training:

- the learning rate (how big each step is), and

- the batch size (how many examples you look at at once).

Instead of only lowering the learning rate over time (which is common), Seesaw lowers it a bit less and increases the batch size at the same time. This keeps the training progress steady but reduces how many serial steps you need, which makes training finish faster.

What questions does the paper ask?

The paper tries to answer:

- Can we replace some learning-rate cuts with increases in batch size and still get the same training quality?

- What is a principled, math-backed way to schedule batch size increases during training?

- How much faster can this make training, especially for very large models?

How did the researchers approach it?

Think of training like walking down a hill toward a goal. The learning rate is the size of each step you take. The batch size is like how many measurements of the slope you average before taking a step. Averaging more measurements (larger batch) reduces noise, so your steps are more reliable.

Here’s what they did:

- They studied standard stochastic gradient descent (SGD), and a simplified version of Adam called normalized SGD (NSGD). NSGD is an analytical proxy that captures key behavior of Adam.

- They proved that for noisy linear regression (a classic, clean test case), decreasing the learning rate is mathematically similar to increasing the batch size, under certain conditions.

- They extended this idea to NSGD, showing a precise balance: if a scheduler would cut the learning rate by a factor , you can instead cut it by and simultaneously multiply the batch size by . This keeps training dynamics similar while needing fewer serial steps.

They turned this into a practical scheduling rule:

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

Seesaw scheduling (simple version):

- Start with learning rate η₀ and batch size B₀.

- Whenever your usual scheduler would cut the learning rate by α:

-> Set η ← η / √α

-> Set B ← B × α |

Example: If your scheduler would halve the learning rate (α=2), Seesaw says:

- learning rate ← multiplied by , and

- batch size ← doubled.

This keeps the loss curve similar but reduces how many times you need to step, because larger batches can be processed in parallel.

Key terms explained in simple language

- Learning rate: How big a step the model takes each time it updates its parameters.

- Batch size: How many examples the model looks at before making a single update. Bigger batches average out noise better.

- SGD: A basic training method that updates the model step-by-step using small, random batches.

- Adam/NSGD: Popular adaptive methods that adjust step sizes based on the gradients. NSGD is a simplified version used for theory.

- Critical batch size (CBS): The largest batch size you can use before training becomes less efficient (you stop getting the usual benefits).

Main findings

- Theory:

- For SGD in noisy linear regression, they proved a finite-sample equivalence: increasing batch size in steps can mimic decreasing the learning rate, in terms of training risk (how far you are from the best possible).

- For NSGD (a stand-in for Adam), they showed a similar equivalence: schedules are “equivalent” if stays constant, where is the learning-rate decay factor and is the batch growth factor.

- There’s a stability limit: the most aggressive safe choice is . Go beyond that and training can become unstable.

- Under common cosine learning-rate schedules, the maximum theoretical reduction in serial steps is about . That’s the “best you can hope for” in this framework.

- Experiments:

- They trained 150M, 300M, and 600M parameter LLMs at “Chinchilla scale” (a rule of thumb: train on about as many tokens as the number of parameters).

- Seesaw matched the loss dynamics of standard cosine learning-rate decay at the same total compute (FLOPs).

- Seesaw reduced wall-clock time by roughly , close to the theoretical maximum.

- It worked with AdamW (including with regularization like weight decay).

- Important caveat: Seesaw works best at or below the critical batch size. If you push batch sizes too far beyond CBS, the assumption that noise dominates breaks down, and Seesaw can’t match the performance of pure learning-rate decay. In very large-batch regimes, actually decaying the learning rate becomes necessary to keep improving.

Why is this important?

Training giant models can take months and cost a lot. Seesaw gives a simple, principled way to finish faster without hurting the final quality. It uses hardware more efficiently by increasing batch size at the right times, while carefully adjusting the learning rate to keep training stable and effective.

Implications and impact

- Practical speedups: Seesaw is a drop-in replacement for standard step/cosine learning-rate schedules. It can cut training time by around for large runs at or below CBS.

- Cost and energy savings: Faster training means lower compute bills and less energy use.

- Better planning: It gives teams a math-backed rule for batch-size ramps, replacing guesswork.

- Clear limits: It highlights when batch-size increases stop helping (beyond CBS) and when learning-rate decay is essential.

In short, Seesaw shows that if you balance learning rate and batch size like a seesaw—lower one a bit, raise the other more—you can keep the same training progress with fewer steps, and finish much sooner.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following list summarizes what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, with concrete directions future researchers could pursue.

- Theory is restricted to noisy linear regression and normalized SGD; there is no rigorous, finite-sample equivalence proof for Adam/AdamW with coordinate-wise preconditioning, momentum (), bias correction, and decoupled weight decay.

- Assumption that expected gradient norms are variance-dominated () is not operationalized for LLM training; no method is provided to detect when this assumption holds or fails during training and to adapt the schedule accordingly.

- The bounded-risk assumption ( after the first scheduler change) is unverified in deep network settings; practical procedures to estimate , choose the first cut time, and ensure the condition holds are not given.

- Normalized SGD analysis replaces Adam’s per-coordinate preconditioner with a scalar; how anisotropy in gradients and curvature affects the LR–batch equivalence in real Adam remains uncharacterized.

- The divergence constraint (requiring ) is stated and supported by a toy NGD example, but formal instability conditions for Adam/AdamW under large-batch ramping are not proven.

- Equivalence constants are “within a constant factor” without explicit numerical bounds; tighter, quantifiable constants are needed to guide safe LR–batch trades in practice.

- Extension of the equivalence to other optimizers (e.g., LAMB, LARS, Sophia, Adafactor) is not explored; actionable scaling rules for these methods are missing.

- The result is shown for step-decay schedules; a general theory for continuous schedules (cosine, polynomial, linear decay, OneCycle) and the error induced by discretizing them into steps is not provided.

- Seesaw assumes pre-determined decay points from a base scheduler; no data- or noise-aware procedure is provided to trigger batch ramp-ups adaptively based on measured gradient noise scale or curvature.

- When variance-dominance fails (past CBS), the paper hypothesizes Adam/NSGD cannot match LR decay via batch ramp; this is not formally proven for deep networks, leaving a gap in understanding large-batch limitations.

- Interaction between Seesaw and momentum schedules (e.g., tuning with batch size or LR changes) is not analyzed; practical momentum adjustments may recover stability at larger batches.

- The impact of gradient clipping, dropout, label smoothing, auxiliary losses (beyond brief z-loss ablations), and parameter-group-specific settings (e.g., embeddings vs non-embeddings) on the proposed equivalence is unstudied.

- No method is proposed for estimating the critical batch size (CBS) online during training; the paper uses static, approximate CBS values rather than measuring CBS adaptively as noise and curvature evolve.

- Experiments are limited to models up to 600M parameters, C4 data, T5 tokenizer, and sequence length 1024; external validity to multi-billion–parameter LLMs, longer contexts, mixed datasets, and modern training mixtures remains unknown.

- Only validation loss is reported; downstream task performance, robustness, and generalization effects of Seesaw vs cosine are not evaluated.

- Real wall-clock speedups are inferred from step reductions; per-step throughput changes, communication/computation balance, and platform-specific overheads (data loading, ZeRO states, all-reduce latency) are not measured.

- Energy, memory bandwidth, and hardware efficiency implications of dynamic batch ramping (vs fixed-batch cosine) are not characterized; FLOPs-equality does not imply equal energy or throughput.

- The interplay between microbatching, gradient accumulation, pipeline/tensor parallelism, and Seesaw is unexplored; guidance is needed when device memory limits prevent true batch increases.

- The warmup strategy is fixed (10% tokens); sensitivity of Seesaw to warmup fraction and forms (linear, cosine, exponential) is not studied.

- Stability margins for aggressive schedules near the frontier are not quantified; practitioners lack criteria for safely pushing toward the theoretical limit without divergence.

- No analysis quantifies how LR–batch trades should vary across training phases as gradient noise scale and curvature evolve; schedules may need phase-specific parameters rather than fixed .

- The paper claims noise scale increases during training (aligning with prior work) but does not measure it in LLM runs; verifying this and using it to drive Seesaw adaptively is an open task.

- Effects of weight decay (AdamW) are only explored empirically in an appendix; the theoretical interaction between decoupled weight decay and LR–batch equivalence is not addressed.

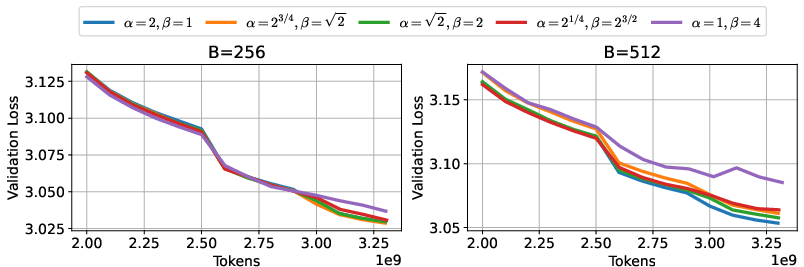

- The Abelian equivalence under the product constraint ( fixed in NSGD) is validated on select points; a more systematic search over a broader grid and different base schedules is needed to map stability/accuracy tradeoffs.

- The continuous-limit derivation of the 36.3% speedup bound assumes cosine and ideal integration; discrepancies due to discrete phase cuts, finite data, and non-ideal hardware are not analyzed.

- Robustness to learning-rate mis-specification is only lightly explored (small LR sweep); sensitivity analyses across wider LR ranges and interaction with are missing.

- No guidance is provided for coordinating Seesaw with other training heuristics (e.g., EMA of weights, SWA, max grad norm), which may interact with noise and stability.

- Seesaw is a drop-in scheduler but lacks deployment guidance for large production runs (checkpoint compatibility when batch changes, dataloader elasticity, scheduler synchronization across workers).

- The effect of data distribution shift or curriculum (data mixing changes over time) on variance dominance and equivalence is not studied; schedules may need to adapt to evolving gradient statistics.

- The theory uses population risk; how Seesaw behaves under finite datasets, repeated epochs, and non-iid sampling (e.g., deduplication, contamination filters) is unexamined.

- No comparison is made with recently proposed batch-warmup heuristics (e.g., “critical batch size revisited” methods) under equal FLOPs and controlled instability thresholds; head-to-head benchmarking is incomplete.

- Guidance on measuring and enforcing the constraint in practice (e.g., through monitored gradient noise scale or loss curvature) is absent; a concrete, implementable stability check would increase reliability.

- Coordination between LR decay points and batch ramp steps for schedules other than cosine (e.g., polynomial, linear, stepwise) is not formalized; a general recipe to generate Seesaw inputs from arbitrary base schedules is needed.

Glossary

- Adam: An adaptive optimization algorithm that uses first and second moment estimates of gradients. "we extend this equivalence to normalized SGD, a tractable proxy for Adam, under a variance-dominated regime observed in practice."

- AdamW: A variant of Adam that decouples weight decay from the gradient-based update. "Seesaw also works even when using AdamW with tuned weight decay in Figure~\ref{fig:weight_decay_losses} of Appendix~\ref{app:weight_decay}"

- additive noise: Random noise added to the target or gradients, commonly used in analyzing linear regression. "linear regression with additive noise."

- batch ramp: A training tactic that increases batch size over time to reduce the number of sequential steps. "Increasing the batch size during training --- a “batch ramp'' ---"

- bias-variance decomposition: A framework decomposing risk into error from bias and variance components. "For discussion, we will use the bias-variance decomposition terminology of risk"

- Chinchilla scale: A compute-optimal scaling rule for LLM pretraining, often described by . "150M/300M/600M-parameter models trained at Chinchilla scale"

- cosine annealing: A smooth learning-rate schedule that decays following a cosine curve. "Seesaw matches the loss dynamics of cosine annealing in FLOPs (top row)"

- critical batch size (CBS): The largest batch size that maintains sample efficiency before performance or speed gains diminish. "beyond a maximum batch size termed as critical batch size (CBS)"

- excess risk: The gap between the risk of the current model and the optimal risk. "Then, the excess risk of the base process is within a constant factor of that of the alternative process."

- finite-sample proof: A non-asymptotic theoretical guarantee that holds for a finite number of samples or steps. "the first finite-sample proof of equivalence between learning-rate decay and batch-size ramp-up for SGD on noisy linear regression"

- FLOPs: Floating point operations; a measure of computational cost. "Seesaw matches cosine decay at equal FLOPs while reducing wall-clock time by "

- learning rate warmup: A technique that gradually increases the learning rate at the start of training. "we do learning rate warmup for of the total amount of tokens"

- normalized gradient descent (NGD): An optimization method that uses gradients normalized by their magnitude, yielding fixed-size steps. "we look at NGD (normalized gradient descent) in 1D"

- normalized SGD (NSGD): A variant of SGD that rescales updates by the expected magnitude of gradients. "Consider a base normalized SGD process (Equation \ref{eq:nsgd})"

- per-coordinate preconditioner: An adaptive scaling factor applied individually to each parameter to adjust effective step sizes. "we approximate the per-coordinate preconditioner of Adam will a single scalar preconditioner"

- population risk: The expected loss over the data-generating distribution. "Let denote the (population) risk of the two procedures at the end of phase ."

- serial runtime: The training time measured in sequential steps, discounting parallelization speedups. "reduces the serial runtime of LLM pre-training runs by approximately "

- step decay scheduler: A learning-rate schedule that reduces the rate by a fixed factor at designated steps. "While our theory is established for step decay schedulers"

- stochastic differential equations (SDEs): Continuous-time stochastic models used to approximate and analyze the dynamics of SGD. "Another point of view for studying the interaction between batch size and learning rate in optimization is through SDEs"

- variance-dominated regime: A training regime where gradient variance terms dominate the mean term, typically influenced by batch size. "a variance-dominated regime observed in practice"

- wall-clock time: The actual elapsed time taken to train a model. "reducing wall-clock time by "

- weight decay: A regularization technique that penalizes large parameter values via a decay term. "Seesaw also works even when using AdamW with tuned weight decay"

- z-loss: An auxiliary loss term used in some training pipelines to stabilize optimization. "we enable z-loss during training"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The paper introduces Seesaw, a principled batch-size/learning-rate scheduler that preserves loss dynamics while reducing serial runtime by ≈36% at equal FLOPs for pretraining-scale models. The following applications can be deployed now, assuming infrastructure supports elastic batching and training is at or below the critical batch size (CBS).

- Software/AI infrastructure: Seesaw scheduler as a drop-in replacement for cosine decay

- What: Implement Seesaw in training loops so that whenever a standard scheduler would halve the learning rate, instead cut by 1/√2 and double batch size; general form maintains α√β constant with stability constraint α ≥ √β.

- Where: PyTorch, JAX/Optax, DeepSpeed/Megatron, Hugging Face Accelerate/Trainer, Keras/TF Addons.

- Value: ≈36% fewer sequential steps (serial runtime) at equal FLOPs with matched validation loss; faster iteration cycles and lower wall-clock costs.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Training at/below CBS; hardware elasticity to increase effective batch without increasing per-step time; distributed data loaders that can change batch at runtime; NSGD-as-Adam proxy holds in variance-dominated regime; step-decay approximation to cosine decay used to identify change points.

- Managed cloud training services: Elastic “Seesaw-aware” training mode

- What: Offer a managed training mode that auto-scales GPU count at scheduler cut points to keep per-step time flat while increasing batch size.

- Where: AWS SageMaker, GCP Vertex AI, Azure ML, OCI Data Science; on-prem SLURM/Kubernetes with TorchElastic/Elastic DDP and DeepSpeed ZeRO for stateful elasticity.

- Value: Reduced job turnaround time; better cluster utilization by deferring part of the GPU allocation to later phases; improved queueing fairness in HPC.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Reliable elastic scaling mid-job (optimizer state sharding, re-sharding checkpoints, data pipeline elasticity); sufficient network bandwidth; autoscaling policies aligned with schedule S.

- Enterprise MLOps: Training workflows and budget planners updated for batch ramp

- What: Update experiment templates to include Seesaw; plan GPU allocations that ramp over time; integrate telemetry to verify α ≥ √β and monitor divergence.

- Where: Internal MLOps platforms (Airflow/Prefect orchestrations, Ray Train, MLFlow).

- Value: Faster model refresh cycles (e.g., weekly pretraining updates), improved developer productivity, controlled compute spend at equal FLOPs.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Data input pipelines scale with batch; CBS estimates available; checkpointing compatible with changing data-parallel world size.

- Sector-specific accelerated model pretraining and domain adaptation

- Healthcare: Faster domain-pretraining for clinical LLMs (EHR notes, radiology reports) to meet deployment timelines and regulatory review windows.

- Finance: Rapid retraining on market shifts for internal LLMs and risk analytics models.

- E-commerce/Advertising: Speedier catalog/creative/multimodal pretraining updates tied to seasonal cycles.

- Robotics/Autonomy: Offline policy/world-model pretraining jobs complete faster, enabling more frequent model refreshes.

- Value: Time-to-model reductions without loss in final performance.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Training scale large enough to benefit; data and privacy governance unchanged by Seesaw; batch ramp stays at/below CBS.

- Academic labs and open-source projects: Faster experiment turnaround at fixed compute

- What: Add Seesaw scheduler to open-source training stacks (e.g., OLMo, LLaMA-style repos, vision pretraining baselines).

- Value: Faster paper iterations and hyperparameter sweeps at equal FLOPs; improved reproducibility by standardizing batch ramp practice.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Access to elastic GPU allocations or node sharing; dataloaders can be reconfigured mid-run.

- Energy and sustainability practices: Lower wall-clock occupancy per job

- What: Schedule Seesaw runs to complete during low-carbon-intensity windows; reduce non-compute overhead energy by minimizing idle time and data-movement-dominated hours.

- Value: Potential energy savings from shorter runtime and better temporal alignment with green power; improved throughput per rack-hour.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Energy gains depend on per-step energy profile; equal FLOPs implies gross compute energy similar, but shorter runtime can reduce overheads; data movement limits may still dominate at frontier scale.

- Tooling and developer utilities

- Seesaw Scheduler libraries: “SeesawLR” for PyTorch/Optax/HF Trainer; a callback that takes an existing schedule S and applies η ← η/√α, B ← B·α at each cut.

- CBS Estimator (pilot runs): A small-run utility to approximate CBS for a given model/dataset, warning when runs move into large-batch regimes where variance dominance fails.

- Guardrail monitors: Runtime checks for divergence when α < √β; alerts when validation loss deviates from baseline cosine beyond a threshold.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Accurate CBS estimation; smooth data throughput at larger batches; stable optimizer state transitions as world size changes.

- Compliance and governance baselines

- What: Adopt Seesaw as a documented training best practice in internal ML standard operating procedures to report efficiency measures alongside FLOPs and carbon intensity.

- Value: Transparent efficiency improvements in model cards and sustainability reports.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Standardized logging of schedule events, batch changes, and final performance; consistent hardware utilization accounting.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, automation, broader validation beyond linear/noisy-quadratic regimes, or deeper systems integration.

- Closed-loop, noise-aware adaptive Seesaw

- What: Online estimation of gradient noise scale to decide when and how much to ramp batch and adjust learning rate (moving beyond precomputed S).

- Value: More robust scheduling across nonstationary phases of training; automatic adherence to α√β = const and α ≥ √β while maximizing speedup.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Reliable, low-overhead noise estimation; robust behavior under non-i.i.d. data and non-convex objectives.

- Full-theory extension to Adam/AdamW and other adaptive optimizers

- What: Theory beyond NSGD proxy to cover AdamW with weight decay, Sophia, Adafactor, optimizers used in modern LLM training, including late-phase dynamics.

- Value: Stronger guarantees and wider safe deployment envelope, especially past warmup and near convergence.

- Dependencies/assumptions: New proofs; empirical validation at larger scales and modalities (vision, speech, multimodal).

- Elasticity-first distributed systems and schedulers

- What: “Batch-ramp-aware” cluster schedulers that co-allocate nodes at forecasted cut points, with seamless optimizer state re-sharding (DeepSpeed ZeRO, FSDP) and dynamic data sharding.

- Value: Minimal disruption during batch changes; improved overall cluster throughput.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Robust elastic DDP; high-bandwidth interconnects; preemption tolerance; job-level SLAs that allow staged scaling.

- Cost and carbon-optimized training planners

- What: Optimizers that choose ramp points and GPU acquisitions to minimize /$\$$ while meeting deadline SLAs, possibly aligning ramps with off-peak pricing or green energy windows.

- Value: Policy-aligned training (green AI targets); predictable budgets.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Accurate electricity price/carbon forecasts; integration with datacenter EMS and cloud cost APIs.

- Cross-domain generalization and curriculum integration

- What: Combine Seesaw with sequence-length schedules, data curricula, and mixture-of-data pacing to co-optimize throughput and convergence.

- Value: Better sample efficiency at fixed FLOPs; stable convergence late in training where variance dominance may fade.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Joint schedulers that balance multiple levers; reliable signals for phase transitions.

- RL and online/streaming learning adaptations

- What: Extend batch ramp logic to off-policy RL/offline RL and streaming data, where gradient noise and stationarity differ from supervised pretraining.

- Value: Faster policy/model updates with controlled stability.

- Dependencies/assumptions: New stability analyses for non-i.i.d., non-stationary settings; safe exploration constraints.

- Large-batch endgame strategies

- What: Hybrid schedules that transition from Seesaw to pure LR decay or variance-boosting techniques when operating beyond CBS (where variance dominance fails).

- Value: Maintain performance late in training; avoid NGD-like limit cycles near the optimum.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Detecting the onset of mean-dominated regimes; smooth handoff policies.

- Standardization and reporting guidelines

- What: Community standards (conferences, consortia, funders) requiring disclosure of batch-ramp practices and efficiency results alongside FLOPs.

- Value: Comparable efficiency reporting; encourages adoption of principled schedules.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Agreement on metrics; reproducible benchmarks.

- Sector-level services and products

- Healthcare/Finance/Energy: “Seesaw-as-a-Service” offerings that package elastic training, CBS estimation, and guardrails for regulated sectors, with audit logs and governance hooks.

- Education: Teaching modules and labs demonstrating the LR–batch-size equivalence and practical scheduler design.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Compliance with sectoral privacy/security requirements; verifiable reproducibility.

Key Assumptions and Dependencies (affecting feasibility)

- Validity regime: Most effective at or below the critical batch size (CBS); performance alignment degrades past CBS as variance domination breaks.

- Theory scope: Formal equivalence proven for SGD on noisy linear regression and extended to NSGD under variance-dominated assumption; Adam/AdamW evidence is empirical at present.

- Stability constraint: To avoid divergence, maintain α ≥ √β; “most aggressive” safe choice uses α = √β.

- Hardware elasticity: Real wall-clock gains require more devices as batch increases; gradient accumulation alone can preserve FLOPs equivalence but not necessarily wall-clock speedups.

- Systems readiness: Dataloaders, samplers, and distributed optimizers must support changing batch/world size mid-run; robust checkpointing and state migration are required.

- Scheduling approximation: Seesaw uses step-decay landmarks to approximate cosine decay; production implementations should validate exact cut points for their schedules and datasets.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.