- The paper demonstrates a reinforcement learning model that integrates prefrontal control with hippocampal-inspired episodic memory for flexible, goal-directed generalization.

- Results from a Morris water maze task show that aligned context cues and top‐down modulation significantly reduce navigation steps in exploit trials.

- Findings indicate that biologically-inspired architectures, particularly with blocked training, enhance adaptability and efficient memory retrieval in dynamic tasks.

Flexible Prefrontal Control over Hippocampal Episodic Memory for Goal-Directed Generalization

Introduction

The paper presents a novel reinforcement learning model that leverages the interaction between the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampus (HPC) to achieve goal-directed generalization. The model addresses the capacity to retrieve and adapt episodic memories based on the current task demand, which is a critical aspect of adaptive behavior and decision-making in novel scenarios. By emulating these neural interactions, the model offers insights into how structured memory retrieval can benefit artificial agents, which typically struggle with out-of-distribution generalization.

Task Design

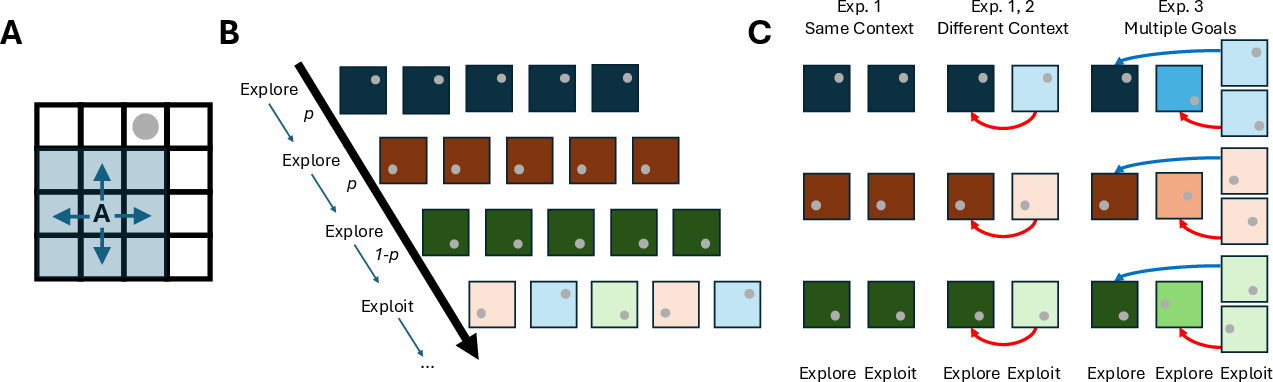

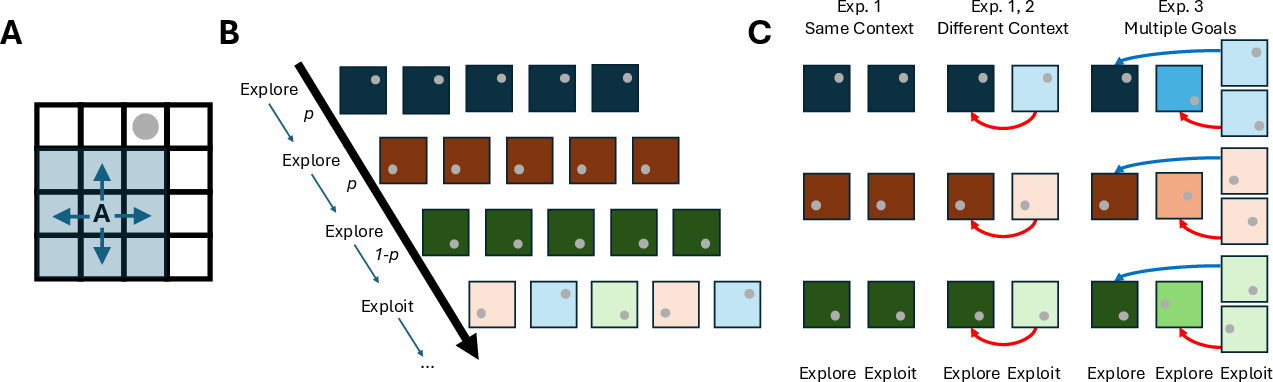

The research designs a simulated reinforcement learning task set within a Morris water maze framework. Agents in the maze must find a hidden platform using partial observations and structural cues. The task is split into episodes consisting of exploration of new mazes and exploitation of previously encountered mazes. Crucially, the context cues can vary, inducing structural changes in learning tasks (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Task structure detailing the reinforcement learning maze and context cues.

Agent Architecture

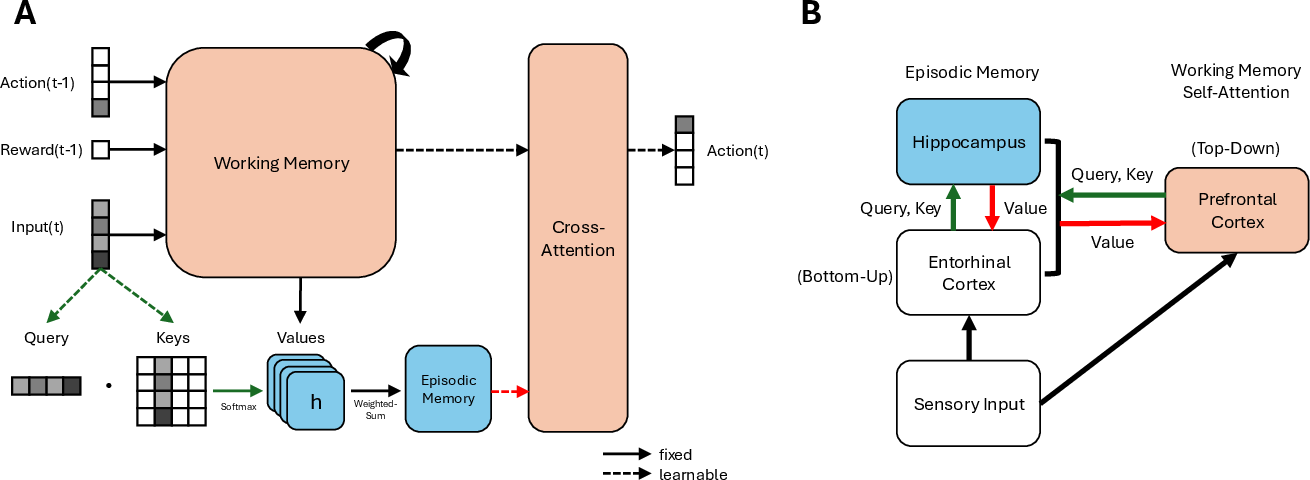

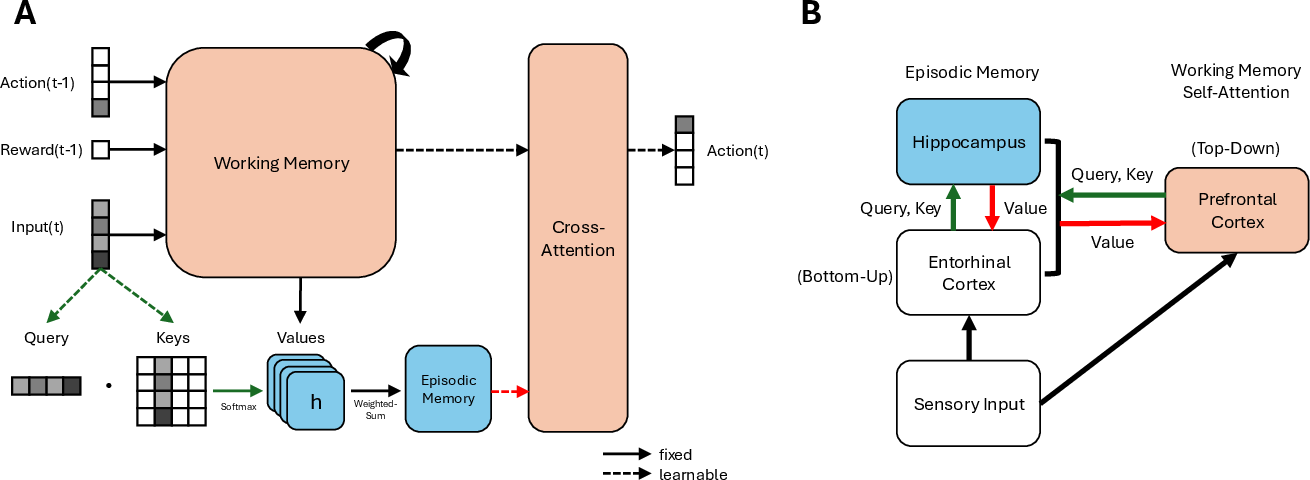

The agent architecture combines a recurrent neural network (RNN) for working memory with a key-value episodic memory system inspired by HPC functionalities. The PFC governs memory retrieval through top-down modulation, enhancing structural association learning over mere sensory similarity. This architecture aims to simulate flexible memory retrieval akin to biological systems (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Overview of the agent architecture showcasing components akin to prefrontal cortex-hippocampus interactions.

Experiment 1: Context-Specific Episodic Memory Retrieval

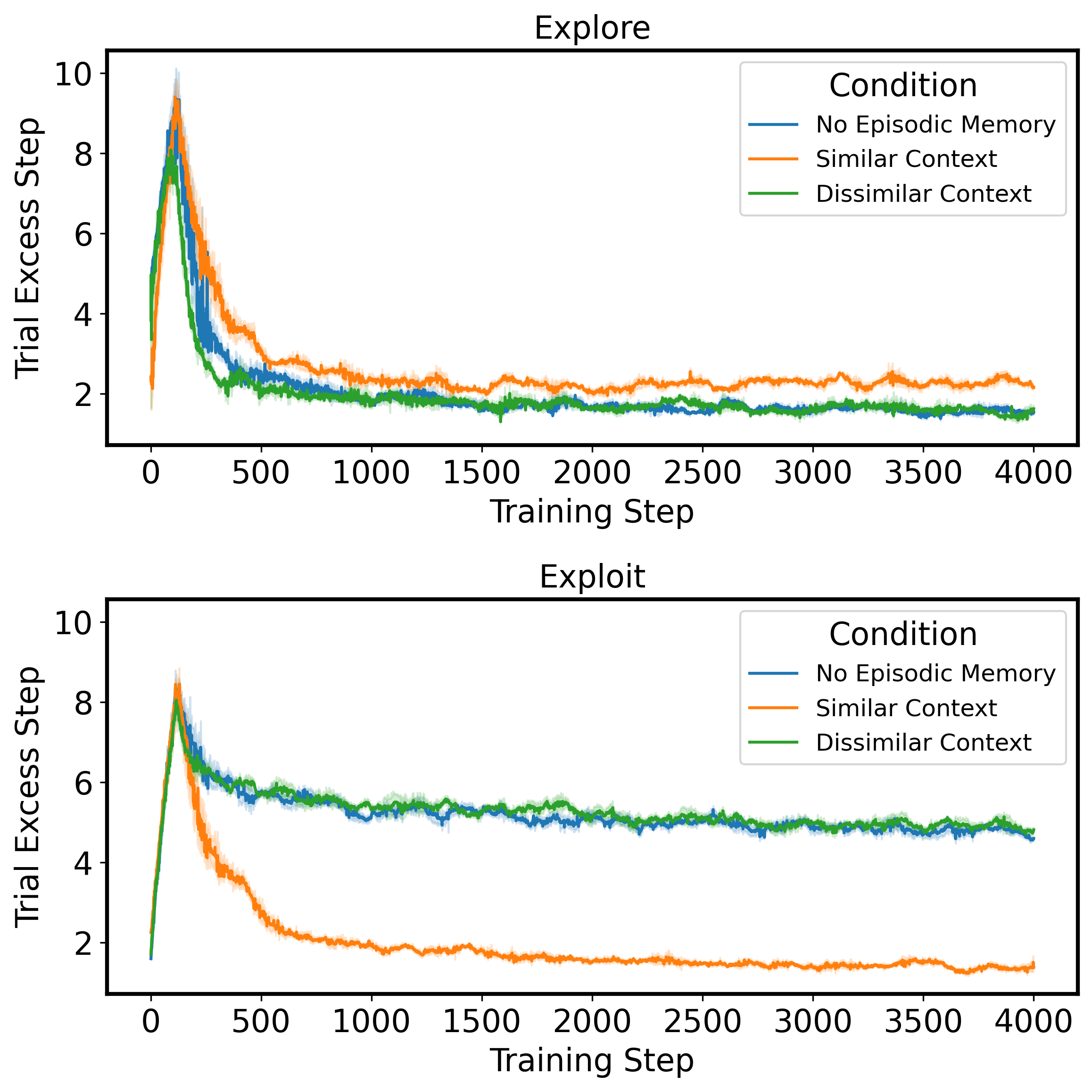

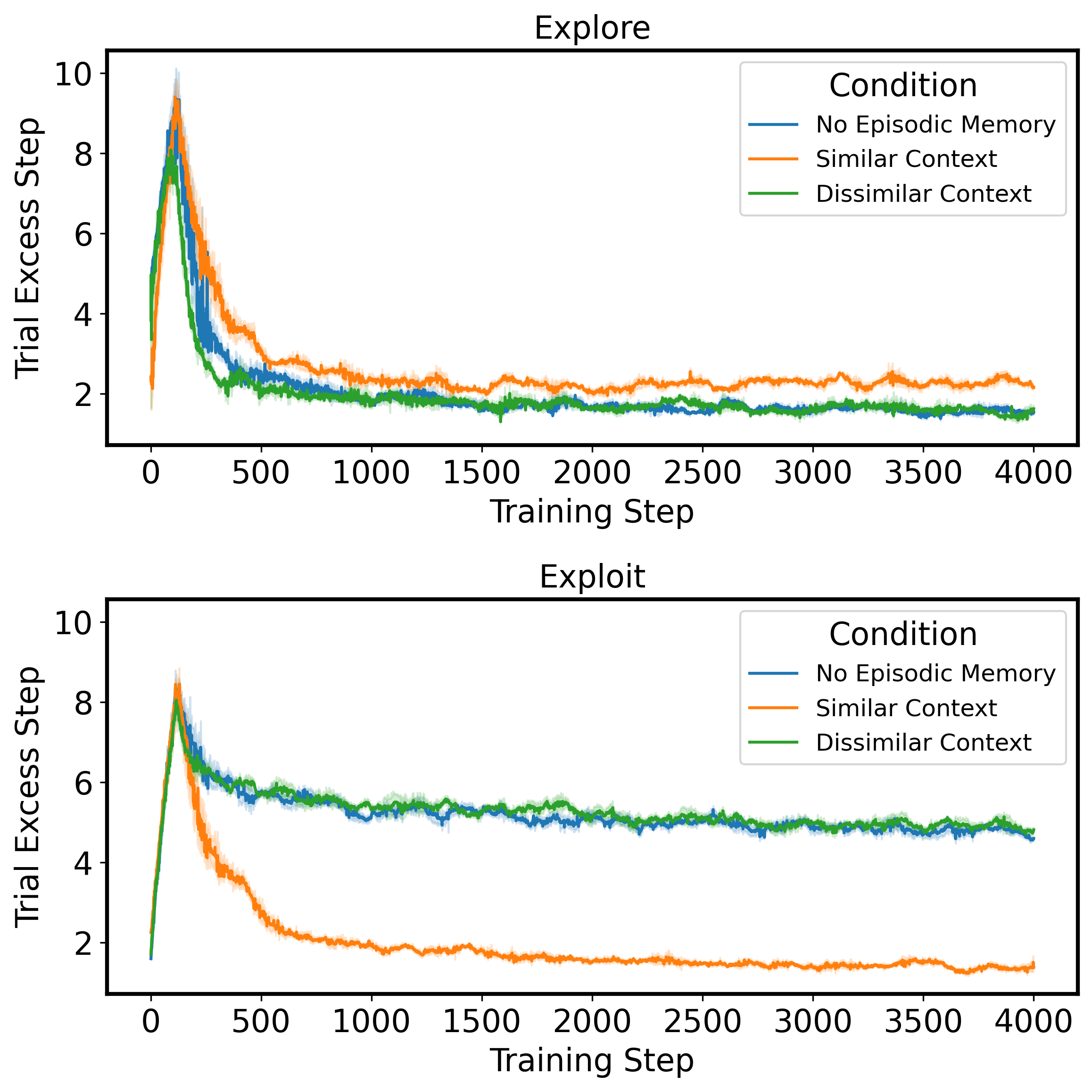

In the first experiment, episodic memory retrieval aligns with encoding specificity, where matching context cues facilitate memory retrieval. The results demonstrate significant improvements in exploit episodes when context cues were congruent, as opposed to situations without episodic memory or with dissimilar cues. These findings underscore the importance of suitable contextual overlap for memory utilization (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Outcomes demonstrating reduced steps when context cues align during exploit trials.

Experiment 2: Structural Learning via PFC Modulation

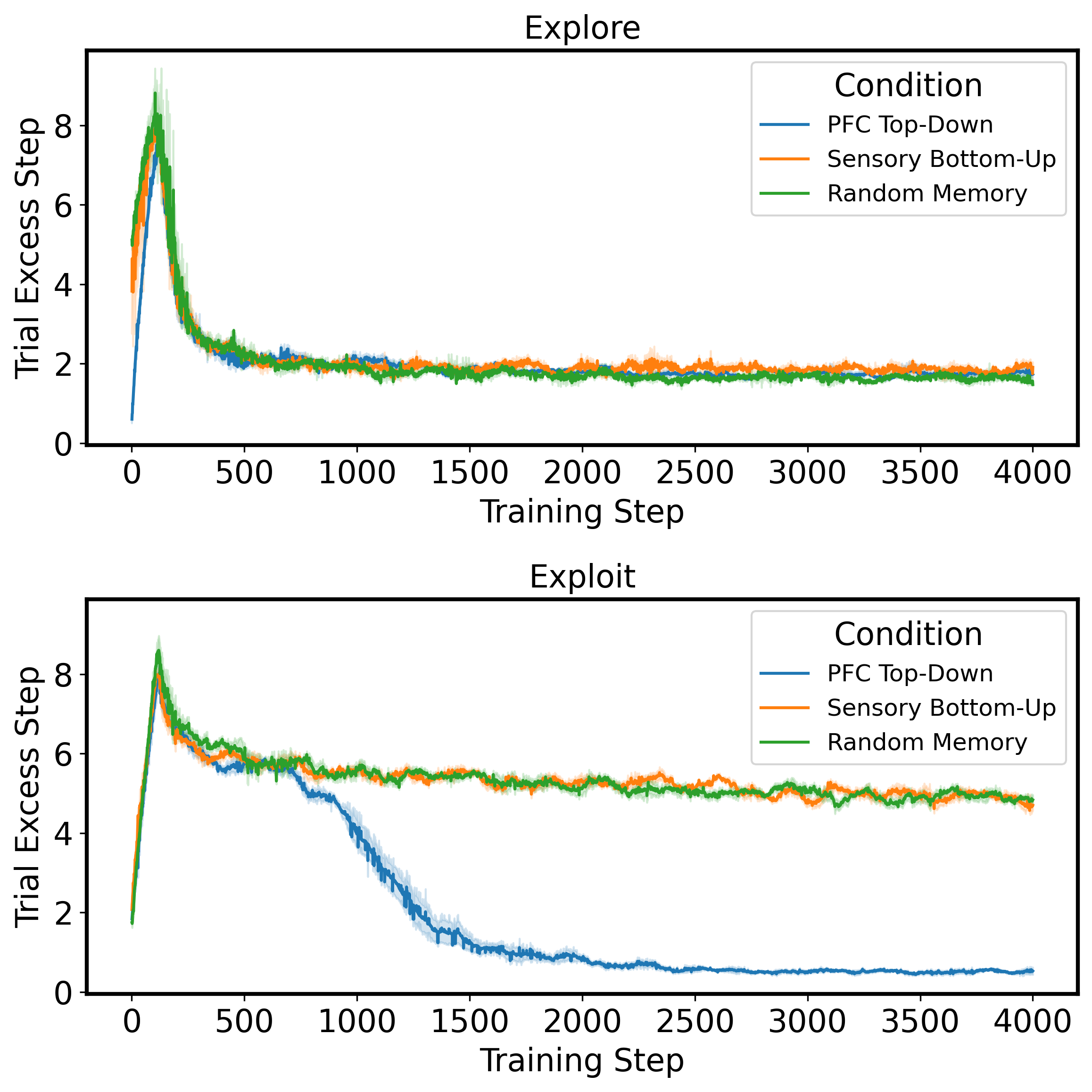

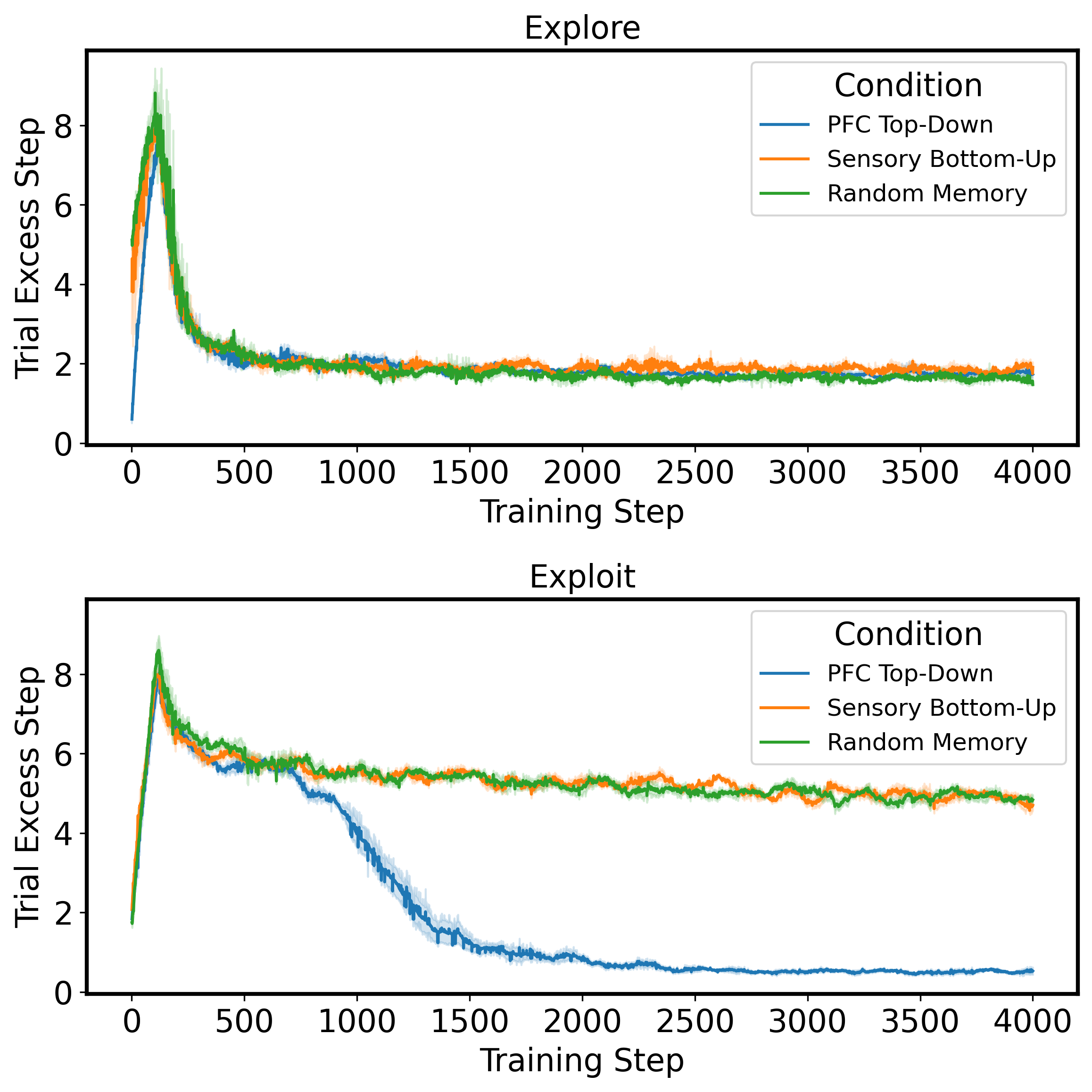

The second experiment explores structural learning, where PFC modulates episodic memory based on task structure instead of sensory data. By leveraging top-down control, the agent performs better in exploiting abstract, non-similar situations—functionally related but perceptually distinct—showing superior results compared to sensory-driven retrieval conditions (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Performance comparison between PFC top-down modulation and sensory-driven conditions.

Experiment 3: Goal-Dependent Flexible Memory Retrieval

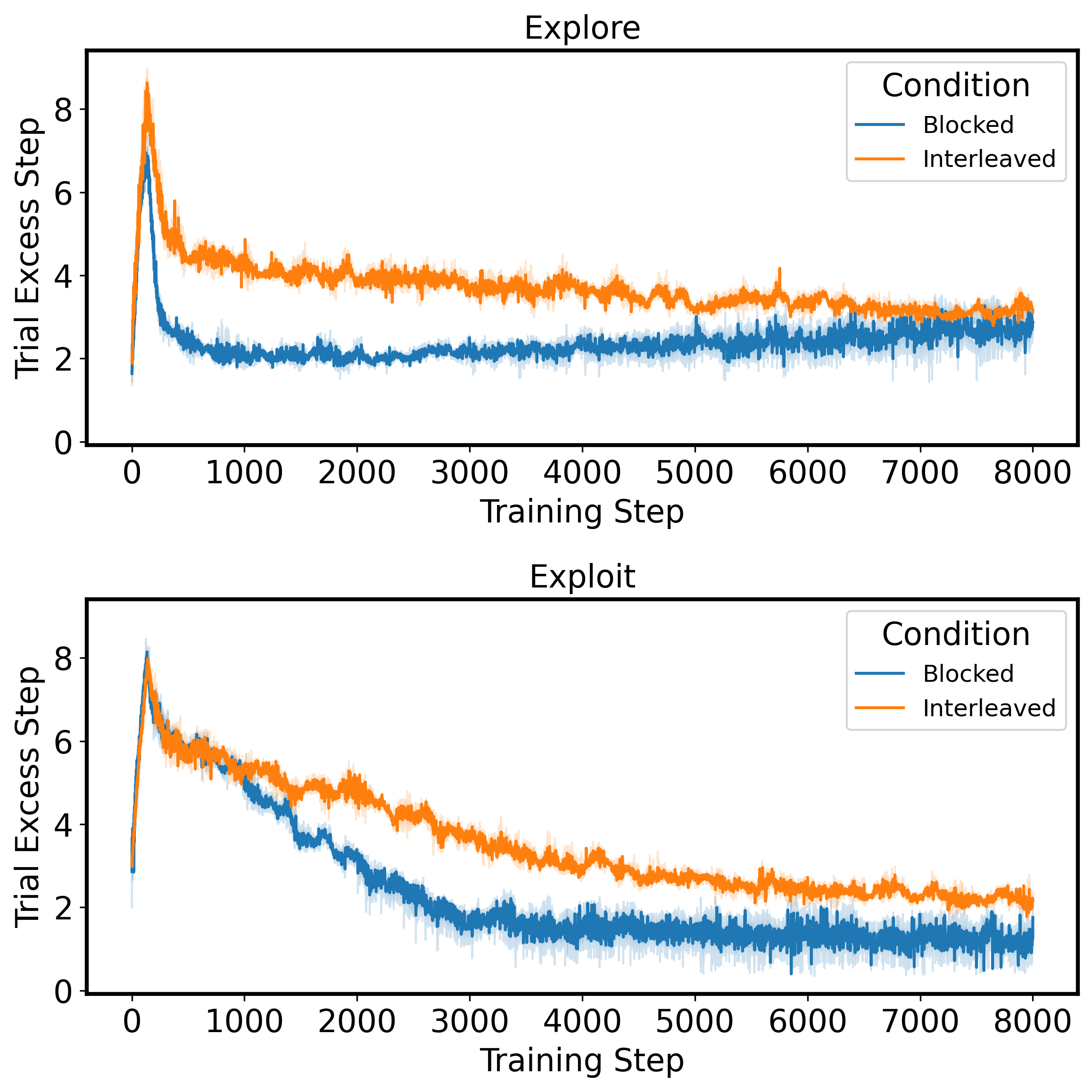

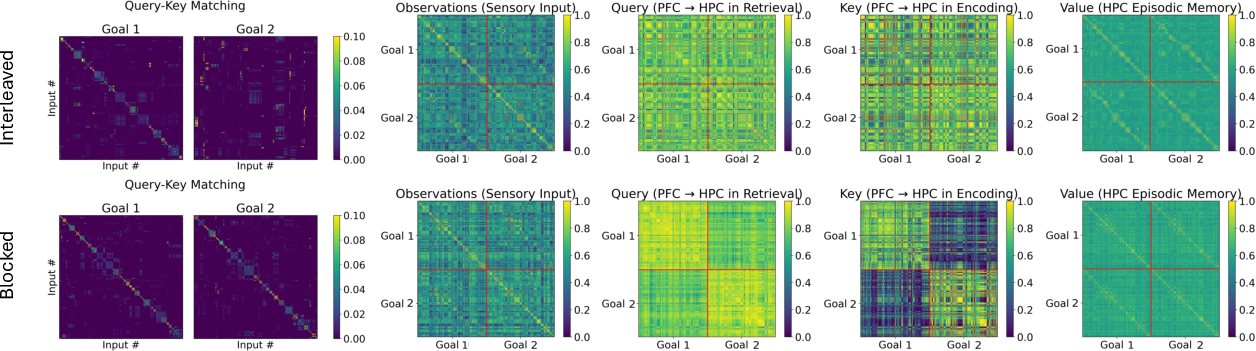

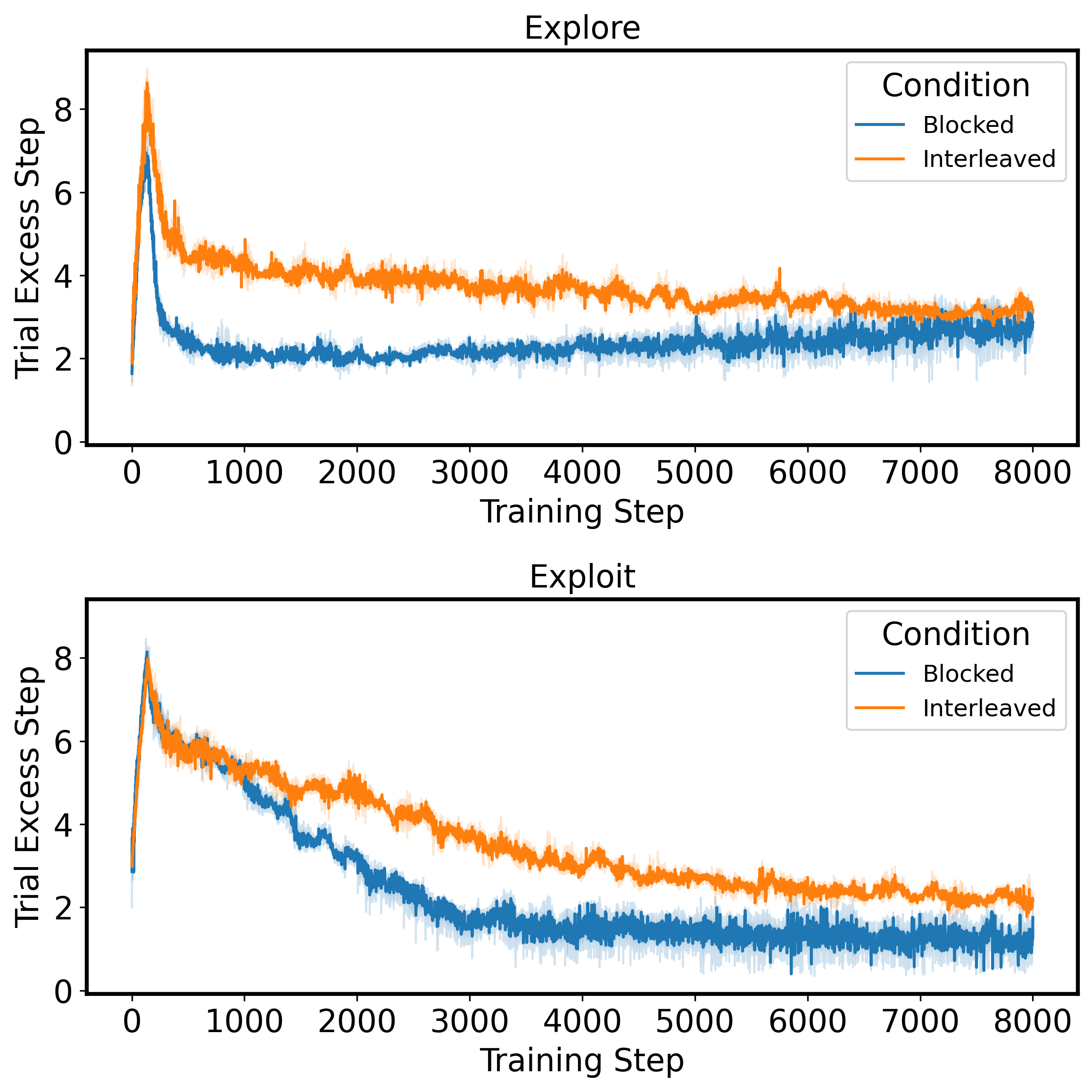

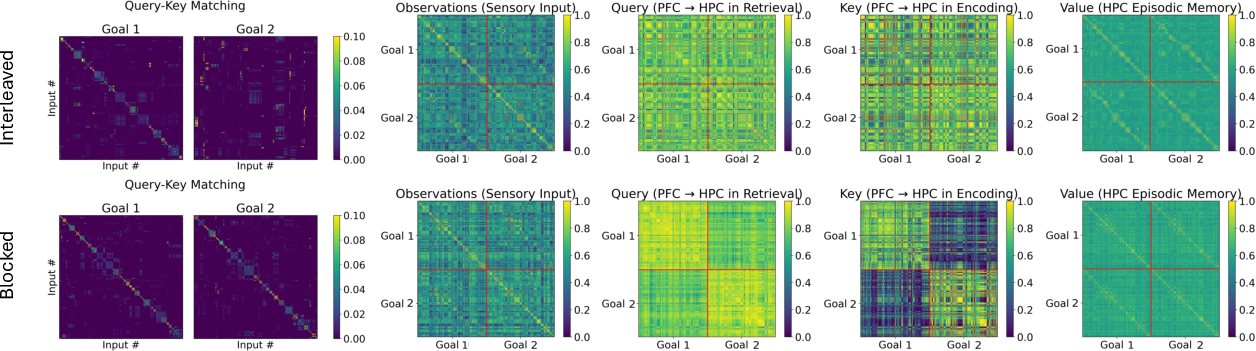

The third experiment extends context manipulation to multiple goals, with agents learning goal-specific structural transformations. Blocked training, contrary to interleaved training, enhances structural learning for goal-specific cues, indicating the benefits of focused learning episodes on maintaining clean memory representations (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Comparison of blocked vs. interleaved training performances in learning decisions for multiple goals.

Figure 6: Analysis of memory representations depicting within-goal and between-goal similarities.

Implications and Future Directions

This research highlights the potential for PFC-HPC inspired architectures to achieve flexible goal-directed generalization in artificial systems. The model emphasizes the need for structured memory retrieval mechanisms in AI, suggesting enhanced training protocols like blocked learning can improve learning efficiency. Future work may involve integrating biologically plausible consolidation methods, enhancing the scalability and complexity of underlying structures, and examining algorithms for algorithmic reasoning.

Conclusion

The paper offers a comprehensive approach towards modeling flexible episodic control through PFC-top-down modulation, which significantly impacts goal-directed learning and decision-making in dynamic environments. The insights gained from this model contribute to the development of AI systems mirroring the adaptive, context-sensitive wiring found in biological brains.