An Interactive UI to Support Sensemaking over Collections of Parallel Texts

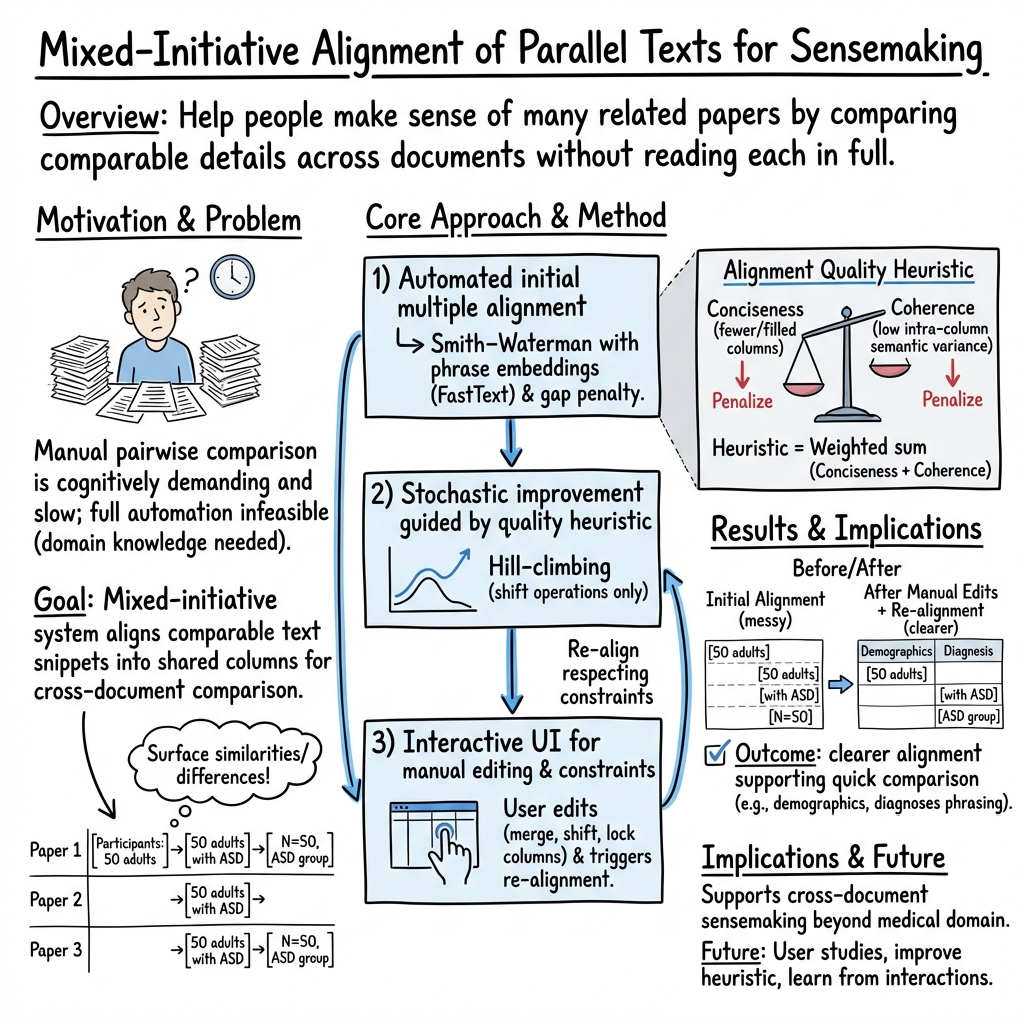

Abstract: Scientists and science journalists, among others, often need to make sense of a large number of papers and how they compare with each other in scope, focus, findings, or any other important factors. However, with a large corpus of papers, it's cognitively demanding to pairwise compare and contrast them all with each other. Fully automating this review process would be infeasible, because it often requires domain-specific knowledge, as well as understanding what the context and motivations for the review are. While there are existing tools to help with the process of organizing and annotating papers for literature reviews, at the core they still rely on people to serially read through papers and manually make sense of relevant information. We present AVTALER, which combines peoples' unique skills, contextual awareness, and knowledge, together with the strength of automation. Given a set of comparable text excerpts from a paper corpus, it supports users in sensemaking and contrasting paper attributes by interactively aligning text excerpts in a table so that comparable details are presented in a shared column. AVTALER is based on a core alignment algorithm that makes use of modern NLP tools. Furthermore, AVTALER is a mixed-initiative system: users can interactively give the system constraints which are integrated into the alignment construction process.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces a tool that helps people make sense of many research papers at once. Instead of reading every paper from start to finish, the tool lines up similar pieces of text (like who the study participants were, what treatments were used, and what outcomes were measured) side-by-side in a table. This makes it easier to compare papers and spot patterns or differences quickly.

Key Objectives

The authors aim to:

- Help readers (like students, journalists, and scientists) compare many papers without getting overwhelmed.

- Combine human judgment with AI so the person stays in control while the computer does helpful organizing work.

- Line up “parallel texts” (short, comparable excerpts pulled from papers) so similar details sit in the same column—making it easier to see what’s common and what’s different.

How the System Works

Think of this tool like organizing recipes from different cookbooks. You want to line up ingredients, cooking times, and steps so you can compare them easily. This system does something similar for research papers.

Here’s the approach explained with simple ideas and analogies:

- Parallel texts: These are short snippets from papers that all talk about the same kind of thing—for example, the “Participants” part of medical studies. Imagine collecting all the “ingredients” sections from various recipes.

- Alignment: The tool arranges these snippets in a table so that comparable details land in the same column (like putting all the “age” info together, all the “conditions” together, and all the “treatments” together).

- Initial alignment (finding matching parts first): The system uses a well-known method called the Smith-Waterman algorithm. In everyday terms, it looks for the best-matching parts between two snippets and lines them up. It keeps doing this, adding one snippet at a time, to build a full table.

- Word embeddings (measuring similarity): The system turns words into number codes using a technique called FastText. Words with similar meanings get similar codes. This helps the tool decide which pieces belong together (like recognizing that “diabetics” and “diabetic patients” are closely related).

- Improving the alignment (smart trial-and-error): After the first pass, the system runs a “stochastic hill-climbing” search. In plain language, it tries small changes—like nudging cells left or right—and keeps changes that make the table better. It uses a score to judge “better.”

- The scoring (what makes a good table): The system prefers tables that are:

- Concise: Not too many columns, and not lots of empty space.

- Coherent: Each column should group texts that mean similar things (for example, don’t mix age groups with medical conditions in the same column).

- Mixed-initiative (working together): You can edit the table yourself:

- Merge cells when words should be treated as one (like “high-functioning”).

- Split columns when a cell contains multiple ideas that should be separated.

- Shift cells left or right to fix misalignments.

- Lock columns to tell the system, “Don’t change this part.”

- After your edits, you can ask the system to re-align based on your guidance.

Main Findings

The paper doesn’t present a big, formal user study. Instead, it shows a detailed example (“usage scenario”) of a researcher studying autism (ASD) and anxiety:

- The researcher collects short “Participants” phrases from several papers (e.g., “Fifty children with high-functioning ASD and anxiety”).

- The tool aligns these phrases into columns, helping separate parts like:

- Group size (e.g., “Fifty”)

- Group description (e.g., “children,” “high-functioning”)

- Diagnosis/action (e.g., “diagnosed with”)

- Conditions (e.g., “ASD,” “ADHD,” “anxiety”)

- With a mix of manual tweaks (merging acronym cells, deleting stray punctuation, shifting certain words, and locking columns) plus automatic re-alignment, the final table becomes clearer and easier to read.

- The scoring method helps keep similar ideas grouped and reduces clutter.

Why this is important:

- It shows that combining human edits with AI suggestions can quickly organize messy, varied text.

- It helps people spot patterns (like which age groups were studied or which conditions were commonly paired) without reading every paper in full.

Implications and Impact

- Faster reviews: Students, journalists, and researchers can get a big-picture view of many papers much faster.

- Smarter comparisons: Lining up details side-by-side makes similarities and differences obvious, which can reveal gaps in research (e.g., under-studied age groups).

- Human in control: The system doesn’t replace expert judgment—it enhances it. You decide the structure; the AI helps tidy it up.

- Broad use: While the example is medical studies, the approach could work for other fields—like comparing methods across machine learning papers or summarizing social science findings.

In short, this tool makes reading and comparing lots of papers more like organizing a neat spreadsheet than flipping through a stack of documents. It’s a practical step toward making research easier to understand and share.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored, structured to guide future research and development.

- Lack of empirical evaluation: No user study (qualitative or quantitative) assesses whether the system improves sensemaking speed, accuracy, cognitive load, or satisfaction compared to baselines (e.g., manual review, Zotero, CollateX, TraviZ). Design and report controlled experiments with task performance metrics and instruments like SUS and NASA-TLX.

- Absence of ground-truth benchmarks: No annotated datasets of “gold” multiple alignments exist for evaluating alignment accuracy. Create domain-specific benchmarks (e.g., medical, ML) with inter-annotator agreement to validate both the initial alignment and re-alignment quality.

- Heuristic validation and tuning: The alignment quality heuristic (conciseness/coherence) is not empirically validated, and component weights are unspecified. Perform sensitivity analyses, ablation studies, and weight optimization (e.g., via grid search or learning-to-rank) to quantify impact on alignment outcomes.

- Limited search operators in automation: The automatic search uses only the “shift” operator; split/merge operators are excluded due to poor interaction with the heuristic. Investigate improved objective functions or multi-objective formulations that enable robust use of splits/merges, and compare alternative search methods (beam search, simulated annealing, random restarts, genetic algorithms).

- Risk of local optima and dependence on start state: Progressive Smith–Waterman alignment and hill-climbing without restarts can yield suboptimal alignments dependent on input order. Explore strategies for ordering inputs (e.g., clustering-based progressive alignment), random restarts, or global optimization to reduce sensitivity to initialization.

- Scalability and performance: No complexity or runtime analysis is provided for large corpora (thousands of texts or long phrases). Benchmark time/memory costs for tokenization, progressive alignment, and search; evaluate interactive latency; introduce caching or pruning to maintain responsiveness.

- Tokenization and phrase segmentation quality: The system exhibits issues with hyphenated terms, acronyms in parentheses, and long condition names, requiring manual merges. Integrate robust tokenization and multiword expression detection (e.g., rule-based handling of hyphens/parentheses, POS/chunking, dependency parses) and quantify improvements.

- Substitution matrix and embedding choices: Smith–Waterman scoring uses L2 distances of average FastText vectors; this may miss contextual nuances, semantics of multi-token phrases, and domain-specific terminology. Evaluate contextual embeddings (e.g., SciBERT, BioBERT), concept normalization (UMLS), synonym/abbreviation resolution, and numeric-aware similarity for better alignment decisions.

- Numeric and unit semantics: Counts (e.g., “23”, “Fifty”), ages (“children”, “adults”), and clinical qualifiers (“clinically significant”) are treated as generic tokens. Design rules/models to detect and normalize numeric/measurement semantics and align them consistently (e.g., sample sizes, age brackets, units).

- Negation and polarity handling: Phrases like “no anxiety” or “previously undetected” invert meaning but are not explicitly modeled. Add negation detection and polarity-aware alignment constraints to avoid misleading column coherence.

- Constraint language expressiveness: Column locking is coarse-grained; users cannot specify higher-level schema constraints (e.g., “pre-diagnosis segment”, “demographics vs condition vs outcome”). Develop richer constraint primitives (typed columns, adjacency/grouping constraints, regex/concept-based locks) and evaluate their usability.

- Mixed-initiative learning: The system does not learn from user edits (e.g., merges, splits, locks) to adapt future alignments. Implement preference learning or active learning to propose edits, prioritize operations, and personalize the heuristic to a user/domain.

- Visualization choices and readability: The paper uses table-like examples but provides no comparative evaluation against other visualizations (e.g., subway maps, hierarchical trees). Conduct studies to test readability, error detection, and comprehension for different visualization modes and for long or dense texts.

- Automatic column labeling and summarization: Columns are not automatically labeled (e.g., Population, Condition) and distributions (e.g., counts by category) are not computed. Add automatic labeling (via concept mapping) and aggregate views (histograms, summaries) to support synthesis and reporting.

- Error propagation from extraction: Reliance on external extraction tools (e.g., PICO_Parser) is acknowledged, but robustness to noisy/incorrect extractions is not analyzed. Quantify performance under varying extraction error rates and incorporate denoising or confidence-weighted alignment.

- Domain generalization: Only small medical-themed examples are shown; applicability to other domains (e.g., ML methods, social science) is untested. Evaluate cross-domain performance and assess whether domain-specific models or ontologies are needed.

- Handling many-to-many correspondences: A single paper may contain multiple phrases for the same schema category or multi-faceted phrases that map to multiple columns. Extend the model to support overlapping spans, hierarchical columns, or multi-span-to-column mappings.

- Parameter defaults and selection rationale: Choices like a 50-step search limit and 0.5 greedy vs 0.5 random step probability are not justified. Perform parameter sweeps and report trade-offs between computational cost and alignment quality.

- Progressive alignment order effects: Input text order strongly affects initial multiple alignment. Study ordering strategies (e.g., clustering by semantic similarity) and quantify their impact on final alignment and user effort.

- Formalization of constraints and guarantees: The semantics of column locks and “boundary” constraints are informal; no guarantees are provided about operations respecting constraints under complex edits. Define a formal constraint system and prove or empirically validate constraint compliance.

- Reproducibility and missing appendices: Key implementation details (exact heuristic combination, substitution matrix computation) are deferred to appendices that are not provided. Publish the full formulas, weights, code, and datasets to enable replication.

- Collaboration and provenance: The system’s support for multi-user workflows, change tracking, undo/redo, and provenance of edits is unspecified. Design and evaluate collaborative features, versioning, and audit trails.

- Multilingual and cross-lingual alignment: The approach is English-centric; no support or evaluation for multilingual corpora. Investigate cross-lingual embeddings and concept normalization to align parallel texts across languages.

- Ethical and interpretability concerns: Misaligned columns could conflate distinct attributes (e.g., age vs sex), risking misinterpretation. Add interpretability aids (column explanations, alignment rationales), warnings for incoherent columns, and bias auditing for demographic attributes.

Glossary

- Alignment modification operators: Operations that transform one alignment into another during search (e.g., shifting cells, inserting columns). Example: "the edges are alignment modification operators that transform one alignment to a different one."

- Alignment quality heuristic: A scoring function that evaluates how good an alignment is to guide optimization. Example: "using an overall alignment quality heuristic."

- Citation networks: Graphs connecting papers via citations to show scholarly relationships. Example: "extracting or predicting citation networks"

- Cognate-based alignment algorithm: A method that aligns text using cognate similarity (shared form/etymology) to detect reuse. Example: "uses n-gram overlap, greedy string tiling, and a cognate-based alignment algorithm \cite{Simard1993UsingCT} to evaluate text reuse in news agency copy text."

- Co-authorship: The relationship/network of authors who publish papers together. Example: "co-authorship with a graph where author groups are represented with nodes"

- Co-mentions: The co-occurrence of specific topics or terms within documents or corpora. Example: "co-mentions of specific topics \cite{Hope2020SciSightCF}."

- Collocation: The tendency of terms to appear together in proximity within text. Example: "visualizes the frequency that extracted medical terms are collocated"

- Covariance matrix: A matrix capturing pairwise covariances among vector components. Example: " calculates the covariance matrix of an input matrix "

- Deep NLP methods: Neural-network-based techniques for language understanding and extraction. Example: "uses deep NLP methods to identify PICO elements of paper abstracts and standardize references to medical concepts using the UMLS classification system."

- Edit distances: Measures of string dissimilarity based on the minimal number of edits needed to transform one string into another. Example: "highlights segments with nonzero edit distances"

- FastText: A library/model that learns word embeddings using subword information efficiently. Example: "we use FastText \cite{Mikolov2018AdvancesIP, Bojanowski2017EnrichingWV, Joulin2017BagOT} to find the set of word embeddings (or phrase embeddings, calculated as the average of each of the word embeddings in a phrase)"

- Gap penalty: A cost applied for introducing gaps in sequence/text alignment. Example: "The Smith-Waterman algorithm itself uses "gap penalty" and "substitution matrix" heuristics to determine whether a given pair of columns from each input alignment should be aligned together or a gap should be inserted instead."

- Greedy string tiling: An algorithm for detecting maximal common substrings between texts. Example: "uses n-gram overlap, greedy string tiling, and a cognate-based alignment algorithm \cite{Simard1993UsingCT} to evaluate text reuse in news agency copy text."

- L2 norm: The Euclidean length of a vector; used as a distance measure between embeddings. Example: "based on the L2 norm between the average phrase vector embeddings of the texts in each input column being considered for alignment together."

- Mixed-initiative system: A system where humans and automation collaboratively share control and decision-making. Example: "Furthermore, \ is a mixed-initiative system: users can interactively give the system constraints which are integrated into the alignment construction process."

- Multiple alignment: The alignment of more than two sequences/texts simultaneously into shared columns. Example: "We wrote a stochastic search algorithm that can improve an existing multiple alignment, centered around original heuristic alignment quality score."

- n-gram overlap: A similarity measure based on shared contiguous sequences of n tokens. Example: "uses n-gram overlap, greedy string tiling, and a cognate-based alignment algorithm \cite{Simard1993UsingCT} to evaluate text reuse in news agency copy text."

- Parallel texts: Comparable text excerpts intended to be aligned for cross-document comparison. Example: "an alignment algorithm which takes a collection of parallel texts as input and produces an "initial" alignment table"

- Philology: The study of the historical development and relationships among texts. Example: "In philology, the study of historical development of literary texts, one of the most common tasks is to highlight correspondences and divergences between different versions of texts originating from the same sources."

- Phrase embeddings: Vector representations of multi-word phrases, often computed by averaging word embeddings. Example: "word embeddings (or phrase embeddings, calculated as the average of each of the word embeddings in a phrase)"

- Phrase trie: A trie data structure whose nodes represent phrases rather than individual words. Example: "compresses the word trie into a phrase trie."

- PICO: An evidence-based schema for structuring medical literature: Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome. Example: "the PICO (Patient-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome) medical paper abstract structure"

- PICOS: An extension of PICO that includes Study design. Example: "Alternative tools such as SPIDER \cite{Cooke2012BeyondP} and PICOS \cite{Methley2014PICOPA} have also been proposed to better handle qualitative and mixed-methods research papers."

- Sensemaking: The process of organizing and interpreting information to build understanding. Example: "it supports users in sensemaking and contrasting paper attributes by interactively aligning text excerpts in a table so that comparable details are presented in a shared column."

- Smith-Waterman local alignment algorithm: A dynamic programming algorithm for optimal local sequence alignment. Example: "It does this by repeatedly using the Smith-Waterman local alignment algorithm \cite{Smith1981IdentificationOC}."

- State space: The set of all possible configurations considered by a search algorithm. Example: "To do this, we run a stochastic hill-climbing algorithm over the state space of all valid alignments"

- Stochastic hill-climbing: A local search method that probabilistically chooses improvements, sometimes taking random steps. Example: "To do this, we run a stochastic hill-climbing algorithm over the state space of all valid alignments"

- Substitution matrix: A table of scores for matching or mismatching tokens during alignment. Example: "The Smith-Waterman algorithm itself uses "gap penalty" and "substitution matrix" heuristics to determine whether a given pair of columns from each input alignment should be aligned together or a gap should be inserted instead."

- Subway map (visualization): A visualization style resembling transit maps used to show parallel sequences and divergences. Example: "Visualizations for text collation usually use some kind of text alignment in a table or "subway map" format which emphasize which segments of texts are identical or different."

- Text collation: The comparison and alignment of different versions of a text to highlight similarities and differences. Example: "Visualizations for text collation usually use some kind of text alignment in a table or "subway map" format which emphasize which segments of texts are identical or different."

- Tokenization: The process of splitting text into tokens (words/subwords) prior to analysis. Example: "Given N input parallel texts, the initial alignment algorithm tokenizes each input text and generates a multiple alignment with N rows, where each row contains one of the input texts, readable from left to right."

- Trace (matrix): The sum of the diagonal elements of a square matrix. Example: " calculates the trace of an input matrix "

- UMLS classification system: The Unified Medical Language System, a standardized biomedical terminology framework. Example: "standardize references to medical concepts using the UMLS classification system."

- Word embeddings: Vector representations of words capturing semantic and syntactic properties. Example: "we use FastText \cite{Mikolov2018AdvancesIP, Bojanowski2017EnrichingWV, Joulin2017BagOT} to find the set of word embeddings (or phrase embeddings, calculated as the average of each of the word embeddings in a phrase)"

- Word trie: A trie data structure over words that organizes strings by shared prefixes. Example: "It builds a word trie starting from either the right or the left as specified containing all of the texts within the specified column and compresses the word trie into a phrase trie."

Practical Applications

Overview

This paper introduces a mixed-initiative, interactive UI and algorithmic pipeline for aligning collections of “parallel texts” (e.g., comparable phrases across documents) into a table where semantically comparable details appear in shared columns. It combines:

- A Smith–Waterman–based multiple alignment to bootstrap an initial table.

- A stochastic hill-climbing search guided by a conciseness-and-coherence heuristic (using FastText embeddings) to refine alignments.

- Human-in-the-loop editing via operations (shift, merge/split/insert/delete columns/cells) and constraints (e.g., column locks), enabling experts to impose schemas and correct or guide the system.

Below are practical, real-world applications derived from these methods and innovations.

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be piloted today with modest engineering and workflow integration, especially for small-to-medium corpora and English-language texts.

- Literature reviews and rapid evidence syntheses (Academia, Healthcare)

- Use the UI to align PICO-like snippets (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) across abstracts to rapidly compare populations, measures, and outcomes; enables quick gap-spotting and summarization.

- Leverages: embedding-based alignment for synonyms/acronyms; column locking to enforce domain schemas; shift/merge/split for cleanup.

- Tools/workflows: a plugin for Zotero/Obsidian; add-ons for Rayyan/Covidence; a “parallel-text panel” in Semantic Scholar.

- Assumptions/dependencies: availability/quality of PICO or similar extraction; reliance on English or well-supported domains; manageable corpus size.

- Science journalism backgrounders (Media)

- Align methods/claims/findings across papers on a topic to identify consensus, disagreements, and scope differences for fast, accurate reporting.

- Leverages: initial multiple alignment + manual constraints to highlight comparable sections across papers.

- Tools/workflows: newsroom research desk UI; browser extension to clip and align snippets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: curated source set; editorial oversight; embedding quality for domain terminology.

- Clinical trial protocol comparison (Healthcare, Pharma)

- Align inclusion/exclusion criteria, endpoints, dosing regimens, and populations across trial protocols/registries for competitive intelligence or planning.

- Leverages: column locking to preserve criteria categories; shift/split operations to standardize granularity.

- Tools/workflows: eTMF/CTMS add-on; dashboard for trial teams.

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to protocol text; PII governance; domain-specific term normalization (e.g., UMLS) improves results.

- Regulatory and compliance document comparison (Finance, Healthcare, GRC)

- Align comparable clauses across versions or jurisdictions (e.g., HIPAA vs. GDPR sections; policy updates) to identify gaps and conflicts.

- Leverages: interactive constraints to maintain clause boundaries; embedding-based matching for paraphrased language.

- Tools/workflows: module in GRC platforms; internal policy comparison tool.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consistent sectioning/headings help; legal review; sensitive document handling.

- RFP/proposal and vendor comparison (Procurement, Enterprise)

- Align requirements and responses across multiple vendor proposals to surface missing commitments, differences in scope, and strengths.

- Leverages: shift/merge to standardize requirement phrasing; column locking to fix requirement schema.

- Tools/workflows: procurement dashboard that ingests RFPs and proposals and auto-aligns key areas.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consistent requirement extraction; domain-specific synonyms; confidentiality.

- Patent landscape triage (Legal/IP)

- Align abstracts/claims/prior art references across patents to quickly cluster similarities and novelty.

- Leverages: embedding similarity for near-paraphrases; manual merges/splits for claim structure.

- Tools/workflows: add-on for patent search tools.

- Assumptions/dependencies: patent-domain tokenization; standardized sections; IP counsel validation.

- Curriculum and syllabus alignment (Education)

- Align learning objectives, assessments, and content coverage across courses or institutions for accreditation or redesign.

- Leverages: column constraints to preserve objective/assessment buckets.

- Tools/workflows: LMS plugin; accreditation prep toolkit.

- Assumptions/dependencies: structured syllabi or extracted sections; instructor buy-in.

- Customer feedback synthesis (Product/UX, Consumer)

- Align user feedback snippets by themes (e.g., pain points, feature requests) across sources (tickets, reviews, transcripts) to prioritize work.

- Leverages: embedding-based grouping + manual refinement to impose product taxonomy; split/merge to manage granularity.

- Tools/workflows: product insights wall; CX analytics integration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: high-quality snippet extraction; privacy compliance; moderate dataset size.

- News event cross-source comparison and fact-checking (Media, Non-profit)

- Align parallel descriptions of the same event across outlets to spot discrepancies and bias.

- Leverages: initial alignment to cluster shared details; column locks to fix entities/timelines.

- Tools/workflows: fact-checker UI for aligned claims/evidence.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consistent event segmentation; multilingual support limited initially.

- Digital humanities and textual collation (Humanities)

- Align variations of texts (e.g., editions/translations) to inspect divergences and shared segments.

- Leverages: shift/merge aligned to philological practice; alignment visualization table.

- Tools/workflows: plugin for CollateX/TRAViz alternatives when experts want tighter human control.

- Assumptions/dependencies: editorial policies; potentially large texts require chunking.

- Knowledge-base/FAQ deduplication (Software, Support)

- Align FAQs or help articles to merge duplicates and consolidate guidance.

- Leverages: embedding-based column coherence to surface overlapping content.

- Tools/workflows: CMS admin panel for deduplication.

- Assumptions/dependencies: content ingestion; taxonomy alignment.

- Model/dataset documentation audit (AI/ML Governance)

- Align model cards or dataset datasheets across teams/models to check completeness and consistency.

- Leverages: column locks for standardized sections; interactive curation of differences.

- Tools/workflows: MLOps governance dashboard.

- Assumptions/dependencies: standardized documentation templates; organizational adoption.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases require additional research, scaling, domain adaptation, or integration with specialized data sources, ontologies, or multilingual capabilities.

- Scalable, semi-automated systematic reviews with active learning (Healthcare, Academia)

- Integrate large-scale extraction (LLMs + PICO/UMLS) with alignment to process thousands of papers; surface candidate evidence tables for expert curation.

- Dependencies: robust extraction at scale; improved heuristics; compute; provenance tracking; bias mitigation.

- Cross-lingual parallel-text alignment (Global health, International policy, Media)

- Align comparable content across languages for multinational studies or policy harmonization.

- Dependencies: high-quality multilingual embeddings; translation fallback; cultural/semantic nuance handling.

- EHR cohort discovery and outcomes synthesis (Healthcare)

- Align free-text problem lists, inclusion/exclusion from clinical notes/discharge summaries to derive cohorts/outcomes.

- Dependencies: PHI privacy/security; clinical ontologies (UMLS/SNOMED); clinical-domain embeddings; validation workflows; institutional approvals.

- Policy and legislative harmonization across jurisdictions (Government, Legal)

- Align statutes/regulations to identify overlaps, conflicts, and gaps across states/countries; support treaty or standards drafting.

- Dependencies: legal-domain NLP; versioning/time-aware comparison; stakeholder governance; political sensitivity.

- Financial analysis and risk monitoring (Finance)

- Align 10-K/10-Q risk sections, MD&A, and earnings call transcripts across companies/time to detect shifts in language and exposure.

- Dependencies: robust parsing of filings and transcripts; temporal alignment; domain-specific lexicons; auditability.

- Safety incident/root-cause analysis at scale (Energy, Aviation, Manufacturing)

- Align narrative incident reports to standardize root causes, contributing factors, mitigations for learning and prevention.

- Dependencies: safety ontologies; confidentiality; cross-site terminology variance; change management.

- Procedure/operations manual consolidation (Robotics, Manufacturing, Logistics)

- Align standard operating procedures across plants/vendors to produce canonical step sequences for training and automation.

- Dependencies: reliable procedure extraction; step segmentation; expert review; integration with training systems.

- Patent drafting and prior art synthesis assistant (Legal/IP)

- Align prior art to suggest phrasing and highlight differentiators during drafting.

- Dependencies: legal acceptability; liability concerns; high-precision alignment for claims language.

- Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) preprocessing (Software/AI)

- Pre-align corpora into schema-consistent chunks to improve retrieval quality and answer grounding for LLMs.

- Dependencies: pipeline integration; evaluation frameworks; domain ontologies to define columns; latency/compute budgets.

- Educational assessment and rubric alignment (Education)

- Align rubrics, standards (e.g., Common Core) and assignments across districts to calibrate grading and instruction.

- Dependencies: standards mapping; teacher tooling and adoption; fairness considerations.

- Open-source license and SBOM compliance alignment (Software, Legal/GRC)

- Align license texts, obligations, and exceptions across components to flag conflicts and required actions.

- Dependencies: license ontology; SBOM ingestion; legal review; continuous integration hooks.

- ESG and sustainability report comparison (Energy, Finance, ESG)

- Align ESG disclosures, metrics, and methodologies across companies and years to improve comparability and auditing.

- Dependencies: evolving ESG standards; metric normalization; assurance workflows.

Notes on Feasibility and Dependencies (Cross-cutting)

- Data preparation: Most use cases require upstream extraction of comparable snippets (e.g., PICO, sections/clauses). Quality here strongly affects alignment.

- Domain adaptation: Embedding models and tokenization may need domain- or language-specific tuning (medical, legal, financial, multilingual).

- Scale and performance: Current approach is well-suited for small/medium sets; large-scale deployments will need batching, indexing, and search optimizations.

- Human-in-the-loop: The mixed-initiative design assumes expert time for imposing schemas (locks), and making fine edits (shift/merge/split).

- Explainability and auditability: Especially in regulated contexts, logging operations, constraints, and provenance is essential.

- Privacy/security: Sensitive corpora (EHRs, internal policies) require secure deployment, access controls, and compliance.

- UI/UX integration: Real impact depends on embedding the UI into existing tools (reference managers, GRC suites, LMS, MLOps dashboards) and workflows.

These applications exploit the paper’s core innovations: mixed-initiative control (column locking and manual operations), alignment bootstrapping via Smith–Waterman, embedding-informed similarity for coherence, and a refinement loop guided by a conciseness/coherence heuristic—together enabling faster, more reliable sensemaking across collections of comparable texts.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.