- The paper presents a comprehensive review of machine learning and AI approaches in GPCR ligand discovery, emphasizing both ligand- and structure-based virtual screening.

- It details various molecular representation techniques, including property vectors, SMILES encodings, 3D voxelization, and graph-based embeddings, to enhance prediction accuracy.

- The work highlights advanced deep learning architectures, generative models, and transfer learning strategies that accelerate bioactive ligand prediction and de novo design.

Machine Learning and AI-based Approaches for Bioactive Ligand Discovery and GPCR-Ligand Recognition

Introduction

This paper presents a comprehensive technical review of ML and AI strategies in computational ligand discovery targeting G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). It systematically examines both ligand-based and structure-based virtual screening (VS), focusing on ML-based approaches, molecular representations, and deep learning (DL) architectures. The work thoroughly discusses the utility of specialized input representations for small molecules, the criticality of architecture selection, recent advancements in deep generative modeling, and the integration of reinforcement learning and transfer learning for design and recognition of GPCR ligands.

Virtual Screening Paradigms for GPCRs

Computational ligand discovery for GPCRs relies on two principal paradigms: ligand-based VS (LBVS) and structure-based VS (SBVS). LBVS operates under the assumption that small molecules with similar properties are likely to share biological activity, leveraging known actives to extrapolate novel candidates without knowledge of receptor structure. In contrast, SBVS incorporates detailed receptor structures, utilizing molecular docking and scoring to prioritize bindings. The review highlights the challenges of LBVS, including the inadequacy of simplistic similarity metrics (e.g., ECFP-Tanimoto), and the acute limitations of SBVS given the scarcity of high-resolution GPCR crystal structures.

Figure 1: Conceptual overview of ligand-based and structure-based virtual screening, with the GPCR ligand 3kPZS and its homology receptor SLOR1 as representative examples.

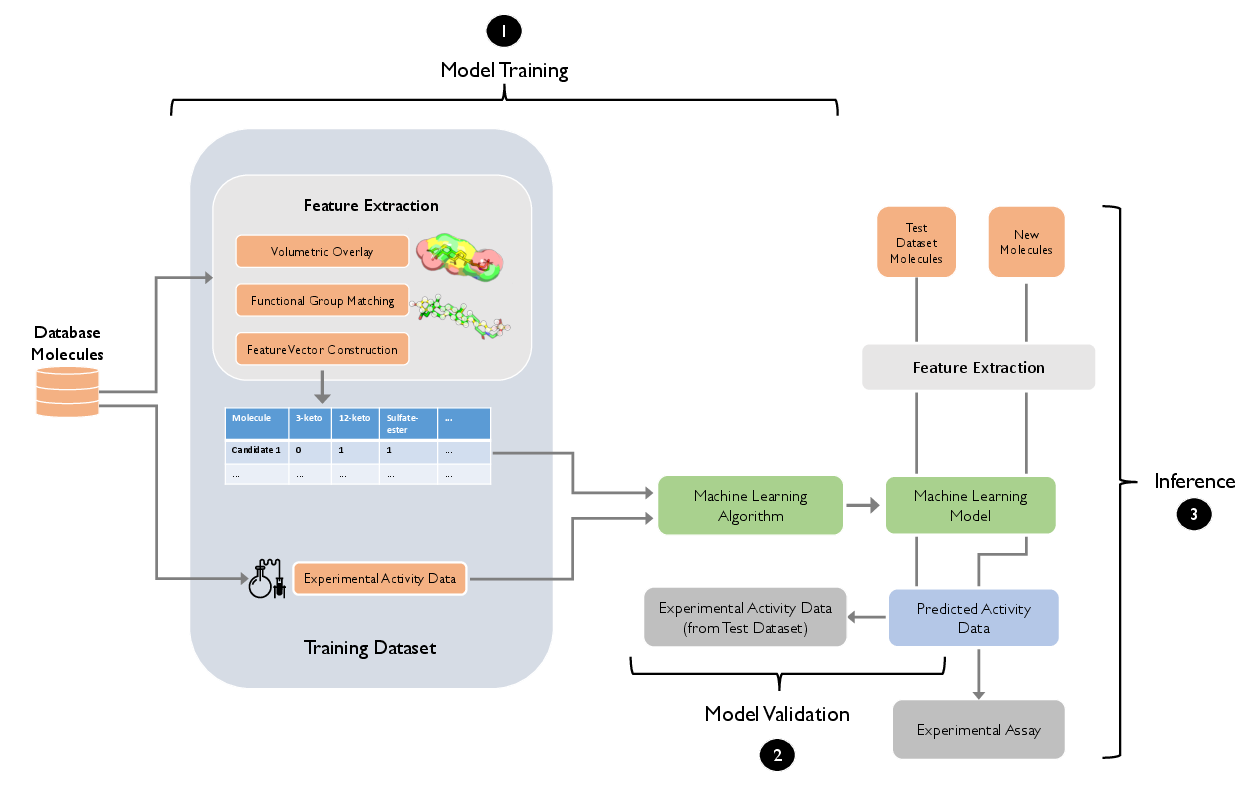

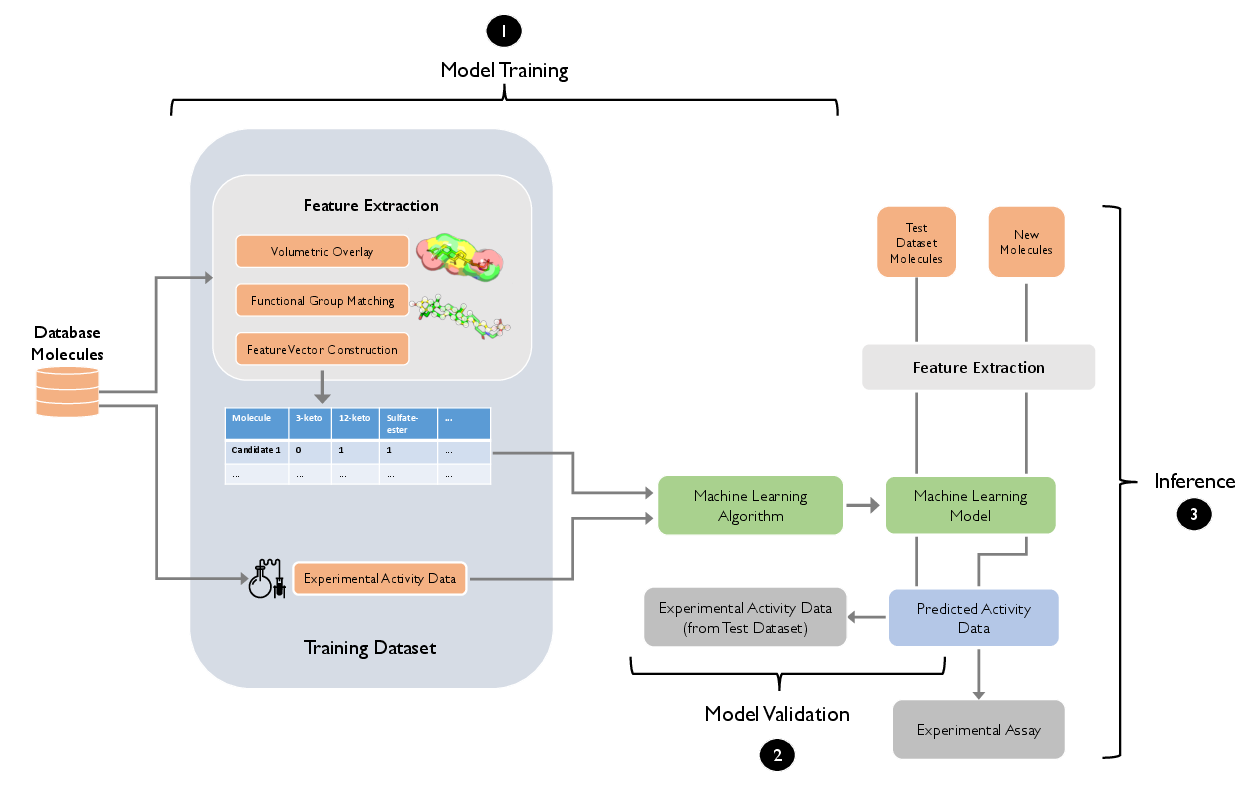

Supervised Learning Workflows for Ligand Recognition

The paper provides a formalization of supervised learning workflows for bioactivity prediction. With an emphasis on robust experimental design, it identifies the necessity of curated, labeled datasets for the training-validation-test pipeline. Classification and regression settings are discussed, with the consensus that classification often exhibits higher robustness in low-signal biological datasets. Feature representations are underscored as a pivotal factor influencing model outcomes.

Figure 2: Supervised learning pipeline for ligand activity prediction, including feature vector extraction, training/validation partitioning, and prospective candidate prioritization.

Molecular Feature Representations

A significant technical discussion is devoted to input representation strategies:

- Property-based vectors: Bit vectors and molecular descriptors (such as ECFP and Dragon/Mordred) remain performant for traditional ML models but are limited in structural expressivity.

- SMILES encodings and sequence-based formats: One-hot encodings of SMILES strings enable compatibility with RNN and 1D CNN architectures; padding and feature matrix strategies resolve issues with variable length.

- 3D voxelization: Grid-based representations are relevant for SBVS and deep docking, despite computational overhead.

- Graph-based methods: GNNs leverage direct chemical graph topology, supporting equivariance and local feature propagation.

Figure 4: Schematic of feature representation options: property/fingerprint, SMILES string, 3D voxel, and graph embeddings illustrated with aspirin.

Deep Learning Architectures for Molecule Property Prediction

Key architectures are described and critically evaluated:

- Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs): Well-suited to dense vector representations (property/fingerprint). Universal approximation is demonstrated but scalability depends on input and label complexity.

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): 1D/2D CNNs process SMILES matrices or molecular images with learned local features. 3D CNNs become relevant for grid-based atomic data.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Represent state of the art for learning on molecular graphs, with message passing frameworks effectively capturing local and non-local structure. The WDL-RF model exemplifies the power of learned molecular fingerprints for GPCR bioactivity regression (2001.06545).

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): Particularly applicable to sequence-based molecular generation tasks.

For interpretability, masked input analysis with CNNs is shown as a viable route for identifying salient sub-sequences critical to binding predictions.

Figure 5: Depiction of interpretability masking in a CNN trained on 1D protein and ligand sequences, revealing sequence regions critical for predicted binding.

Similarity-based and Hybrid Screening

Detailed evaluation of similarity metrics demonstrates that ensemble fingerprinting combined with Tanimoto similarity (e.g., MuSSeL) can achieve robust enrichment, but 3D/physicochemical overlays and hybrid similarity models (e.g., HybridSim-VS) exhibit superior specificity when 3D structure data is available. The eSim method provides statistical superiority over alternative 3D techniques on pharmaceutically relevant benchmarks.

Figure 7: Visualization of molecular similarity: chemical structure, Tanimoto-based 2D fingerprint similarity, and 3D volumetric overlays.

Structure-Based Methods: Binding Site Prediction and Docking

In SBVS, binding site prediction is tackled with both ensemble machine learning models (e.g., random forests in cavity detection) and modern deep learning (e.g., BiteNet—3D CNNs adapted for large membrane receptors through grid partitioning). For docking, the emergence of neural scoring functions—such as DeepAtom, $K_{\text{DEEP}$, and OnionNet—demonstrates numerical advantages over classical scoring, especially when leveraging high-dimensional, multi-scale input representations. RF-score utilizes succinct atom pair feature count matrices for robust affinity prediction. The computational bottleneck in DL-based scoring (Parameter count/O(N3) voxel scaling) is partially alleviated via efficient architectures (e.g., SqueezeNet, ShuffleNet v2).

De Novo Molecule Generation: Autoencoders and Reinforcement Learning

The review covers the theoretical and practical implications of generative models:

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): Architectures that embed molecules into regularized latent spaces, supporting smooth interpolation and continuous optimization for targeted molecular properties. Junction tree VAEs enforce chemical validity while enabling exploration of new chemical space proximal to known actives.

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): Enables explicit optimization of design objectives (e.g., GPCR binding, ADMET properties). Architectures such as REINVENT (policy gradients with RNNs) and DrugEx (combined RL and exploration-exploitation through dual agents) demonstrate the ability to generate and recover diverse, biologically validated ligands. DrugEx achieves broad chemical space coverage for adenosine A2A receptor activity. MOLDQN and related graph-based approaches ensure chemical validity during search by restricting expansion to feasible graph edits.

(Figure 8; Figure 9)

Figure 10: (Top) VAE encoding-decoding of molecules into continuous latent space, supporting de novo generation. (Bottom) RL loop example: state, action, environment transition in molecular graph construction.

Transfer Learning and Its Role in Low-Data Regimes

Transfer learning is highlighted as a practically essential approach; pretrained models on large, chemically diverse datasets are fine-tuned on small data domains (e.g., orphan GPCRs), providing marked increases in downstream accuracy. Examples in 3D-CNN-based docking as well as general property prediction (solubility, quantum properties) reinforce the paradigm's value.

Active and Semi-supervised Learning: Outlook

The review critically notes that active learning strategies—integrating automated model selection of data points for human annotation—are not widely adopted in GPCR ligand discovery but offer substantial gains in model calibration and cost-efficiency. In parallel, semi-supervised and self-supervised paradigms (e.g., language modeling, jigsaw tasks) are expected to enhance robustness in low-label settings. Combining these with transfer learning (active transfer learning) is presented as a highly leveraged yet underexplored research direction.

Implications and Future Developments

ML- and AI-enabled ligand discovery for GPCRs is now largely limited by the availability and quality of data for both ligands and high-resolution receptor structures. The continual growth of public databases and the adoption of open-source toolchains (e.g., RDKit, ChEMBL, ZINC, PyTorch, TensorFlow) lower practical barriers to experimentation with advanced ML architectures. Model selection—spanning representations and learning modality—is problem-specific, and empirical benchmarking remains critical as generalization across GPCR families is not guaranteed.

Active learning systems and improved interpretability tools (e.g., LIME, SHAP, DeepLIFT) are recommended to ensure model transparency and actionable insight for wet-lab experimental design and validation. The application of AI to unresolved experimental challenges such as GPCR deorphanization and high-resolution structure prediction (as exemplified by AlphaFold) will likely drive the field’s next phase.

Conclusion

AI- and ML-driven methods have achieved demonstrable improvements in all facets of GPCR ligand discovery: from hit identification and property prediction to de novo design. While robust architectures, representation selection, and data-centric workflows are critical, the operational bottleneck remains validation: in silico predictions must be systematically verified in biological and chemical assays. Integration of experimental feedback via active/semi-supervised learning, and leveraging transfer learning for rapid adaptation, will be central themes in near-future methodology. Outcomes will depend on further increases in data accessibility, improved model interpretability, and stronger interdisciplinary collaboration bridging computational and experimental sciences.