Pretrained Polymer Representations

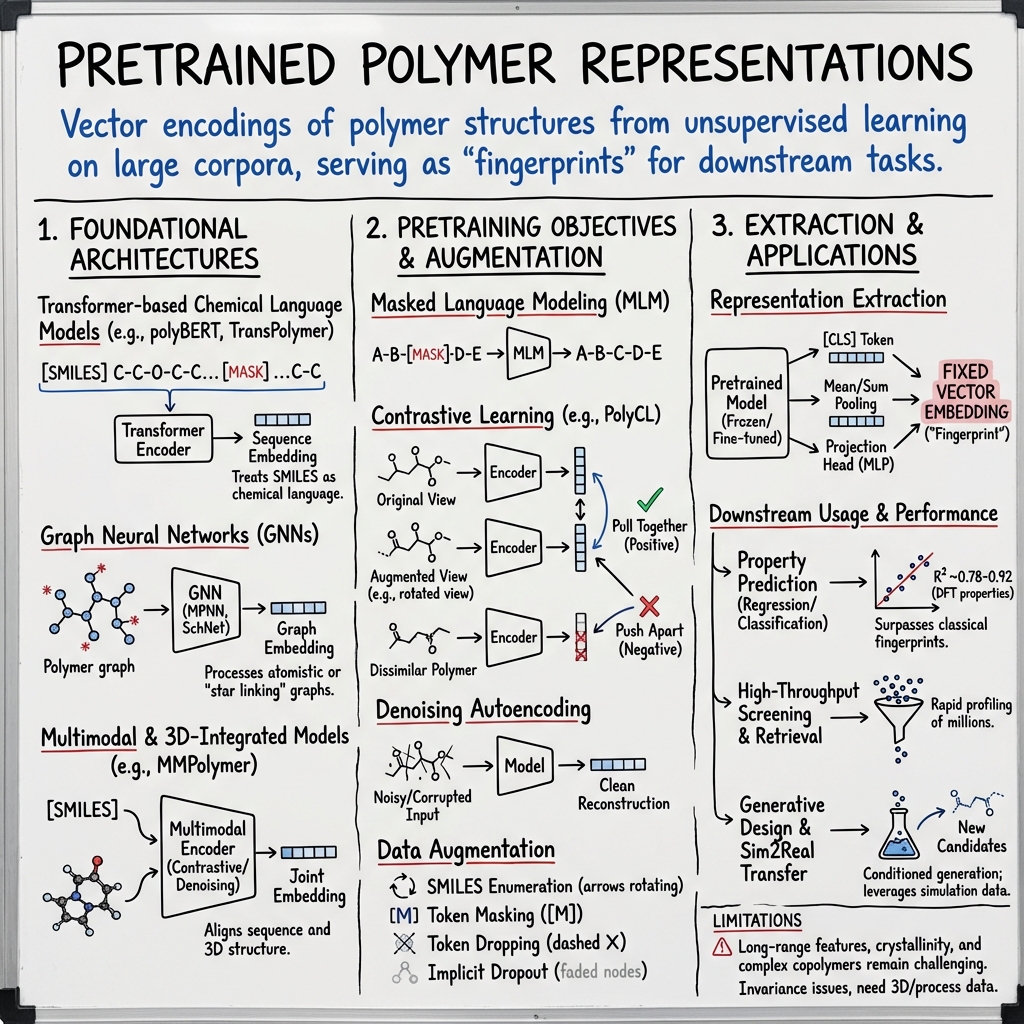

- Pretrained polymer representations are vector encodings capturing chemical and structural features using transformers, GNNs, and multimodal architectures for enhanced prediction accuracy.

- They are developed through self-supervised objectives like masked language modeling, contrastive learning, and denoising autoencoding to extract robust polymer fingerprints.

- These representations enable high-throughput property screening, rapid virtual design, and effective transfer learning across various polymer tasks.

Pretrained polymer representations are vector encodings of polymer structures obtained from unsupervised or self-supervised learning on large polymer corpora, serving as fixed or adaptable "fingerprints" for downstream tasks such as property prediction, retrieval, and generative design. These representations are produced by deep learning models—primarily Transformers, graph neural networks (GNNs), and multimodal architectures—premised on sequence, graph, or 3D-centric inputs specific to polymers. They aim to capture both chemical and structural features relevant to polymers’ unique statistical and compositional diversity, facilitating transfer learning, data-efficient optimization, and rapid virtual screening.

1. Foundational Architectures and Representational Paradigms

Pretrained polymer representations leverage the full array of modern neural architectures customized for the polymer domain:

- Transformer-based chemical LLMs: Models such as polyBERT and TransPolymer treat polymer SMILES as chemical language sequences and utilize masked language modeling (MLM) objectives for self-supervised pretraining (Kuenneth et al., 2022, Xu et al., 2022). PolyCL extends this paradigm with contrastive learning by generating multiple statistically-augmented views per polymer (Zhou et al., 2024). Hybrid LLMs like polyBART employ Pseudo-Polymer SELFIES (PSELFIES) to bridge molecular and polymer representations in an encoder–decoder regime (Savit et al., 21 May 2025).

- Graph neural networks (GNNs): Polymer-specific GNNs process atomistic polymer graphs or induced representations such as “star linking” graphs (which encode infinite polymer chains as finite monomer graphs with artificially closed endpoints) (Wang et al., 27 Jul 2025). Architectures include message-passing neural networks (MPNNs), continuous-filter convolutional models (SchNet), and SE(3)/SO(3) equivariant GNNs for explicit consideration of spatial configuration (Levine et al., 28 Dec 2025).

- Multimodal and 3D-integrated models: MMPolymer aligns SMILES-based sequence encoders and 3D structure encoders via joint contrastive and denoising pretraining, while MIPS and PolyConFM combine infinite-sequence GNNs with explicit 3D spatial features (Wang et al., 2024, Wang et al., 27 Jul 2025, Wang et al., 15 Oct 2025).

- Simulation-informed and kernel-based approaches: Representation learning built on simulation databases (e.g., PolyOmics, OPoly26) distills force-field and DFT-computed features into embedding vectors for transfer to experimental tasks (Yoshida et al., 7 Nov 2025, Levine et al., 28 Dec 2025).

2. Pretraining Objectives, Augmentation, and Tokenization

The construction of robust polymer representations is driven by self-supervised objectives and innovative data augmentations:

- Masked Language Modeling (MLM): The primary objective for SMILES-based models, masking 10–20% of tokens per sequence and optimizing cross-entropy recovery (Kuenneth et al., 2022, Xu et al., 2022). This drives acquisition of polymer “grammar”—patterns of atom connectivity and repeat unit composition.

- Contrastive Learning: PolyCL introduces the NT-Xent loss across augmented SMILES views, pushing encoded representations of different augmentations of the same polymer structure together in embedding space, and dissimilar polymers apart (Zhou et al., 2024). Augmentations include SMILES enumeration, token masking, and token dropping, as well as in-model dropout ("implicit augmentation").

- Denoising Autoencoding: BART-style models (e.g., polyBART) and 3D denoising models (e.g., MMPolymer) reconstruct masked input sequences or perturbed 3D conformations, enforcing information recovery and decorrelating input variation (Savit et al., 21 May 2025, Wang et al., 2024).

- Graph Masking and Cross-modal Alignment: MIPS and MMPolymer add masked atom prediction and alignment of sequence/3D representation spaces via joint contrastive losses (Wang et al., 27 Jul 2025, Wang et al., 2024).

- Domain-specific Tokenization: Tokenization is chemically aware—handling multi-character atoms, branching, and special polymerization boundary symbols (“[*]”). PolyBART’s PSELFIES allow direct translation from molecule to polymer encodings, and TransPolymer’s vocabulary is augmented with tokens for mixture, copolymer, and descriptor information (Savit et al., 21 May 2025, Xu et al., 2022).

3. Representation Extraction and Downstream Usage

Once pretrained, polymer representations are extracted via pooling or projection strategies:

- Fixed-length embeddings: Standard practice is to extract the [CLS] token embedding from the final layer as the polymer fingerprint (commonly 600–768 dim for BERT-style models) (Zhou et al., 2024, Kuenneth et al., 2022). Alternative pooling includes mean-pooling over all tokens.

- Graph readout: For GNNs, mean or sum pooling of node features, often with additional set-attention pooling, is used to obtain molecular-level (or cluster-level) embeddings (Levine et al., 28 Dec 2025).

- Multimodal concatenation and cross-modal fusion: MMPolymer and MIPS concatenate or align sequence-derived and 3D-derived representations for use in multimodal prediction tasks (Wang et al., 2024, Wang et al., 27 Jul 2025).

- Projection heads and downstream models: For regression/classification, a lightweight head (MLP, GPR, or mixture-of-experts) is trained atop the fixed encoder, with the backbone kept frozen or jointly fine-tuned. For generative and design tasks, the pretrained embedding is used as a control variable or decoder input (Savit et al., 21 May 2025, Wang et al., 15 Oct 2025).

4. Benchmarking and Transfer Learning Performance

Extensive cross-model comparisons and transfer learning benchmarks demonstrate the utility of pretrained polymer representations:

| Model/Approach | Mean R² (typical DFT property prediction) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PolyCL (frozen) | 0.7897 (avg. 7 tasks) | (Zhou et al., 2024) |

| TransPolymer | 0.7830 | (Zhou et al., 2024) |

| PolyBERT | 0.7775 | (Zhou et al., 2024) |

| MMPolymer | Best RMSE on 7/8 tasks | (Wang et al., 2024) |

| MIPS | R² = 0.926 (Egc), 0.814 (EPS) | (Wang et al., 27 Jul 2025) |

| PolyConFM | Highest R², RMSE across 8 properties | (Wang et al., 15 Oct 2025) |

PolyCL, PolyBERT, and TransPolymer consistently surpass classical fingerprints (e.g., ECFP+XGB or Polymer Genome), with R² improvements typically ranging from 0.74–0.78 versus 0.67–0.72 for GNN baselines (Zhou et al., 2024). GNNs pretrained on OPoly26 achieve up to 30% lower MAE compared to training from scratch, and PolyOmics-trained MLPs display 10–40% MAE reduction in Sim2Real transfer scenarios (Levine et al., 28 Dec 2025, Yoshida et al., 7 Nov 2025).

A key result is that LLMs pretrained on small molecules can be transferred and fine-tuned for polymer tasks with comparable efficacy to polymer-specific pretraining—provided the downstream properties are local to the repeat unit rather than reliant on mesoscale features such as crystallinity (Zhang et al., 2023).

5. Structural Representation, Control Experiments, and Generalizability

Recent analyses reveal that many SMILES- or sequence-based polymer representations are highly invariant and can unintentionally interpolate over token space rather than learning true chemical semantics. Control experiments demonstrate:

- Randomization or replacement of special tokens (e.g., [*]→[Fe], or token order shuffling) does not significantly diminish test performance after fine-tuning, suggesting that benchmarks predominantly measure interpolation within training distribution rather than chemical understanding (Park et al., 8 Dec 2025).

- Attention maps in LLMs may not encode chemically interpretable information but instead reflect positional or token-pattern biases, unless forced through more stringent OOD splits or chemically-enforcing architectures (Park et al., 8 Dec 2025).

- For robust generalization and genuine foundation model capabilities, OOD splits, 3D or graph-based representations, and control-variant evaluation are recommended (Park et al., 8 Dec 2025).

6. Applications: Retrieval, Screening, and Generative Design

Pretrained polymer representations are deployed across a broad spectrum of applications:

- High-throughput screening: Rapid embedding and property prediction for millions of hypothetical polymers (e.g., polyBERT enables profiling 100 million SMILES in ~30 hours on four GPUs) (Kuenneth et al., 2022).

- Multimodal retrieval and ranking: PolyRecommender fuses language-based and GNN-derived embeddings for candidate retrieval and multi-property ranking, leveraging mixture-of-experts for robust multi-objective optimization (Wang et al., 1 Nov 2025).

- Property-conditioned and unconditional generation: polyBART supports property-conditioned sampling by decoding from the neighborhood of latent vectors corresponding to target properties (Savit et al., 21 May 2025). PolyConFM enables conformation-centric conditional polymer design using generated structure-aware embeddings (Wang et al., 15 Oct 2025).

- Sim2Real transfer learning: Embeddings trained on large-scale simulation data (PolyOmics, OPoly26) can be fine-tuned for real, experimental property prediction with quantifiable scaling-law behavior that supports the "more is better" principle (Yoshida et al., 7 Nov 2025).

7. Limitations, Challenges, and Future Directions

Several challenges persist in the development and deployment of pretrained polymer representations:

- Long-range and mesoscale encoding: Tasks dependent on chain packing, crystallinity, or complex copolymer architectures are inadequately handled by repeat-unit focused representations. Model variants incorporating chain length, topology, stereochemistry, or explicit physical modeling (e.g., classical MD, DFT) are necessary (Zhang et al., 2023, Levine et al., 28 Dec 2025).

- Representation invariance and false generalization: Standard SMILES- or sequence-based representations may yield high test accuracy under random splits without true chemical understanding, necessitating stricter benchmarks and control variants (Park et al., 8 Dec 2025).

- Integration of 3D and process metadata: Incorporating 3D structural data and processing conditions (e.g., temperature, solvent) via multimodal or equivariant architectures is a current research frontier, as seen in MMPolymer, PolyConFM, and OPoly26 (Wang et al., 2024, Wang et al., 15 Oct 2025, Levine et al., 28 Dec 2025).

- Scalability: Pretraining on omics-scale simulation datasets (e.g., >10⁵ polymers in PolyOmics) reveals power-law scaling in transfer performance and enables exploration of previously inaccessible chemical space (Yoshida et al., 7 Nov 2025).

A plausible implication is that future polymer foundation models will interweave large-scale chemical language modeling, graph-theoretic and 3D representations, automated simulation data, and rigorous benchmarking protocols, leveraging scaling-law dynamics to systematically improve real-world applicability.