Parameter-Shift Rule in Quantum Circuits

- The parameter-shift rule is a technique that computes unbiased analytic gradients by evaluating functions at deterministically shifted parameter values, leveraging spectral properties of unitary evolutions.

- It generalizes to arbitrary gate spectra and multi-level systems by formulating derivatives as weighted sums and employing convex or approximate methods to optimize circuit evaluations.

- PSR is crucial in variational quantum algorithms, quantum machine learning, and photonic simulations, reducing noise effects and resource overhead through hardware-compatible estimators.

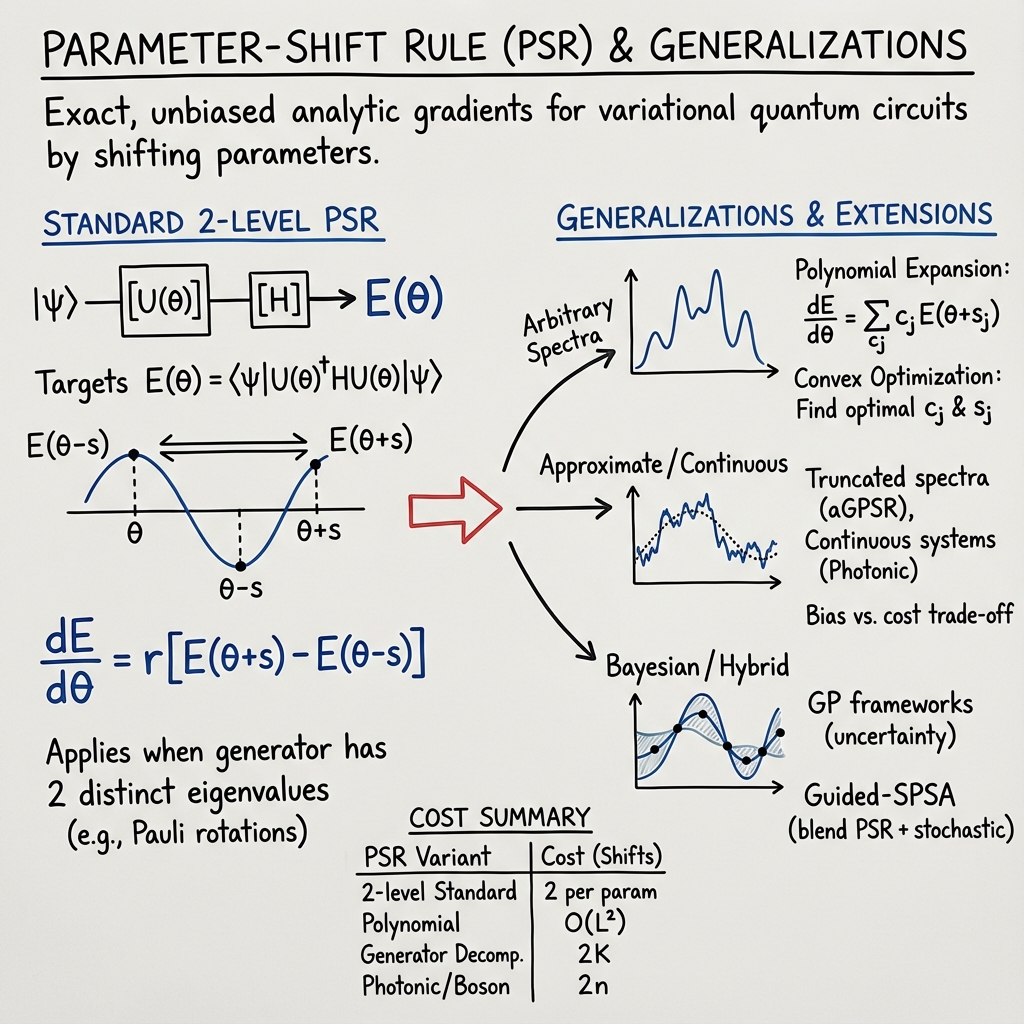

The parameter-shift rule (PSR) is a family of exact and unbiased methodologies for analytic gradient computation of expectation values with respect to variational circuit parameters. Originating in the context of quantum computing for gate-based and photonic platforms, the PSR formulates derivatives as linear combinations of function evaluations at deterministically shifted parameter values. Fundamentally, it leverages the algebraic and spectral properties of parameterized unitary evolutions, replacing standard finite-difference approximations with hardware-compatible, noise-resilient estimators. The PSR has since undergone significant generalizations—encompassing arbitrary gate spectra, multi-level and infinite-dimensional systems, and optimal shift-selection rules—making it a central tool across quantum machine learning, variational quantum eigensolvers (VQE), photonic simulation, and black-box optimization contexts (Izmaylov et al., 2021, Banchi et al., 6 Oct 2025, Pappalardo et al., 2024, Wierichs et al., 2021).

1. Algebraic Foundations and Standard Rule

The canonical PSR targets expectation values of the form

where is a unitary parameterized gate, and is an observable. When the generator of has only two distinct eigenvalues, the function is sinusoidal in , permitting an exact two-point difference formula:

where , and the shift (Crooks, 2019, Robbiati et al., 2022, Periyasamy et al., 2024). For Pauli generators (), this yields the familiar form:

This formula is unbiased and free from discretization artifacts.

2. Generalizations to Arbitrary Gate Spectra

For gates whose generators possess more than two distinct eigenvalues, the commutator algebra and the Fourier decomposition of the expectation function become crucial. The generalized PSR expresses the derivative as a weighted sum over an expanded set of shifted evaluations:

with shifts and weights determined by solving a moment-matching linear system governed by the eigenspectrum of the generator (Izmaylov et al., 2021, Wierichs et al., 2021, Markovich et al., 2023). In the polynomial-expansion PSR, the exponential of a Hermitian generator with eigenvalues is a degree- operator polynomial, yielding shifted terms in the worst case (reduced to if the spectrum is symmetric about zero) (Izmaylov et al., 2021, Theis, 2021). Alternatively, the generator can be decomposed into a sum of operators with smaller spectral support, each permitting a two-eigenvalue PSR at reduced cost ( shifts where is the number of fragments) (Izmaylov et al., 2021).

Recent convex optimization formulations seek coefficients and shift locations that minimize the estimator variance or support, providing provably optimal finite-support generalized PSRs for arbitrary finite spectra (Theis, 2021, Markovich et al., 2023, Banchi et al., 6 Oct 2025). In the case of equidistant spectra, shift points and weights have explicit closed forms, with the cost scaling as for an -level generator (Markovich et al., 2023).

3. Continuous, Approximate, and Bayesian Extensions

When exact computation is infeasible (e.g., for large Hilbert spaces, hardware-induced analog Hamiltonians, or infinite spectra), the parameter-shift rule extends to approximate and continuous regimes. The overshifted PSR introduces excess shift degrees of freedom and selects the optimal linear combination by minimizing the -norm of coefficients under the Fourier-matching constraints, resulting in estimators with minimal shot overhead and practical flexibility for arbitrary spectra—including photonic, qudit, or coupled oscillator systems (Abramavicius et al., 23 May 2025, Banchi et al., 6 Oct 2025).

Approximate generalized rules (aGPSR) further truncate the spectral system, adopting a fixed number of pseudo-gaps and shift points. The induced bias decays rapidly as in the shift size , providing a controllable trade-off between computational cost (number of circuit evaluations) and estimator precision (Abramavicius et al., 23 May 2025).

Bayesian PSR variants embed the derivative estimation into Gaussian-process frameworks, allowing flexible derivative inference at arbitrary sampling points, analytical uncertainty quantification via posterior variance, and adaptive sample reuse—a strategy shown to accelerate VQE optimization while reducing the required circuit budget (Pedrielli et al., 4 Feb 2025).

4. Application Domains: Qubit, Photonic, and Optical Circuits

The PSR paradigm is foundational in variational quantum algorithms, especially for training parameterized quantum circuits (VQCs), quantum machine learning models, and VQE routines. For gate-based qubit architectures, PSR enables hardware-efficient analytic gradients for parameterized unitaries, circumventing the need for ancilla qubits or Hamiltonian simulation (Crooks, 2019, Robbiati et al., 2022, Izmaylov et al., 2021).

Generalizations to photonic circuits resolve the non-unitary derivative challenge in Fock space, using roots-of-unity-based systems or Boson-sampling formalisms. For linear optical interferometers, the PSR scales linearly in the photon number and preserves robustness to loss, indistinguishability, and state mixedness (Pappalardo et al., 2024, Hoch et al., 2024). Specific PSRs tailored to Mach-Zehnder interferometer meshes underpin analytic gradient computation for unitary optical neural networks, exploiting the finite Fourier series character of photonic observables (Jiang et al., 13 Jun 2025).

The table below summarizes core PSR variants, corresponding system settings, and resource scaling:

| PSR Variant | System/Generator Type | Evaluation Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Two-level standard PSR | Qubits, Pauli rotations, 2-level gates | 2 shifts/param |

| General polynomial expansion | Finite- spectrum, arbitrary Hamiltonian | shifts |

| Generator decomposition | Sums of 2- or 3-eigenvalue operators | $2K$ shifts |

| Overshifted/convex PSR | Arbitrary, possibly infinite spectrum | , optimizable |

| Photonic/Boson sampling PSR | Fock space, linear optics (n photons) | $2n$ shifts |

| Approximate (aGPSR) | Arbitrary, large/NISQ, user-chosen | $2K$ shifts |

5. Stochastic, Black-Box, and Hybridization Strategies

Stochastic parameter-shift rules (SPSR) generalize the deterministic PSR by randomizing shift locations or operator selection. The SPSR provides unbiased estimators for multi-parameter gates and non-commuting generator scenarios, exploiting random sampling and averaging over operator fragments or the continuous shift domain (Banchi et al., 2020, Wierichs et al., 2021, Banchi et al., 6 Oct 2025). This is especially relevant for deep, multi-layered circuits where deterministic rules incur high overhead.

In gradient-free or black-box optimization, the PSR can be interpreted as a structured zeroth-order estimator, equating derivatives to symmetric finite differences at optimally chosen shift points, and it is shown that with appropriate calibration, PSR yields machine-precision agreement with analytic gradients even outside quantum settings (Hai, 16 Mar 2025).

Hybrid methods, such as Guided-SPSA (simultaneous perturbation stochastic approximation assisted by PSR), blend exact PSR gradients with stochastic gradient approximations to reduce the quantum shot and circuit budget while maintaining convergence rates, reporting circuit-evaluation reductions of up to 25% over pure PSR-driven optimization (Periyasamy et al., 2024). Such approaches are particularly advantageous for large-parameter models and NISQ-era hardware.

6. Implementation Considerations and Resource Optimization

Resource demands for PSR-driven differentiation scale linearly (standard two-level), quadratically (polynomial expansion), or logarithmically/linearly (CSA or decomposition-based) in the gate’s eigenspectrum size, with hybrid and continuous methods providing favorable trade-offs via convex optimization or adaptive selection of shift points (Izmaylov et al., 2021, Markovich et al., 2023, Banchi et al., 6 Oct 2025). In photonic architectures, PSR maintains scaling with photon number, and in large multi-qubit scenarios, convex or approximate rules cut the number of measurements relative to naive GPSR by factors up to 500× in benchmarked VQE cases (Abramavicius et al., 23 May 2025, Pappalardo et al., 2024).

Calibration of shifts, adjustment for parameter-feature interactions (as in data re-uploading models), and exploitation of symmetry or commutation are necessary to minimize shot noise, stabilize the estimator against hardware imperfections, and reduce classical post-processing cost (Robbiati et al., 2022, Crooks, 2019, Hoch et al., 2024). In Bayesian frameworks, sample reuse and adaptive shot allocation further accelerate optimization with statistically precise uncertainty quantification (Pedrielli et al., 4 Feb 2025).

7. Significance and Outlook

The parameter-shift rule, in its various incarnations, provides the analytic backbone for end-to-end quantum-classical training, enabling efficient, unbiased gradient evaluation within the constraints of contemporary hardware. Algorithmic developments—extending PSR to arbitrary spectra, optimizing for variance or support, embracing stochasticity, and adapting to photonic or continuous-variable platforms—continue to advance the scope and efficiency of variational quantum algorithms. The mathematical framework based on Fourier decomposition, convex resource optimization, and randomized evaluation directly informs theoretical and experimental best practices in quantum optimization, variational eigensolver protocols, quantum machine learning, and optical neural computation (Izmaylov et al., 2021, Banchi et al., 6 Oct 2025, Pappalardo et al., 2024, Pedrielli et al., 4 Feb 2025, Theis, 2021, Markovich et al., 2023).

Key open directions include further reduction of measurement overhead for Hamiltonians with highly degenerate or continuous spectra, dynamic adaptation of shift rules in noisy and drifting environments, full integration with quantum optimal control, and embedding within hybrid classical-quantum inference pipelines. The parameter-shift rule’s generality and extensibility ensure its centrality as quantum hardware, models, and algorithms become increasingly complex and heterogeneous.