From Kepler to Newton: Inductive Biases Guide Learned World Models in Transformers

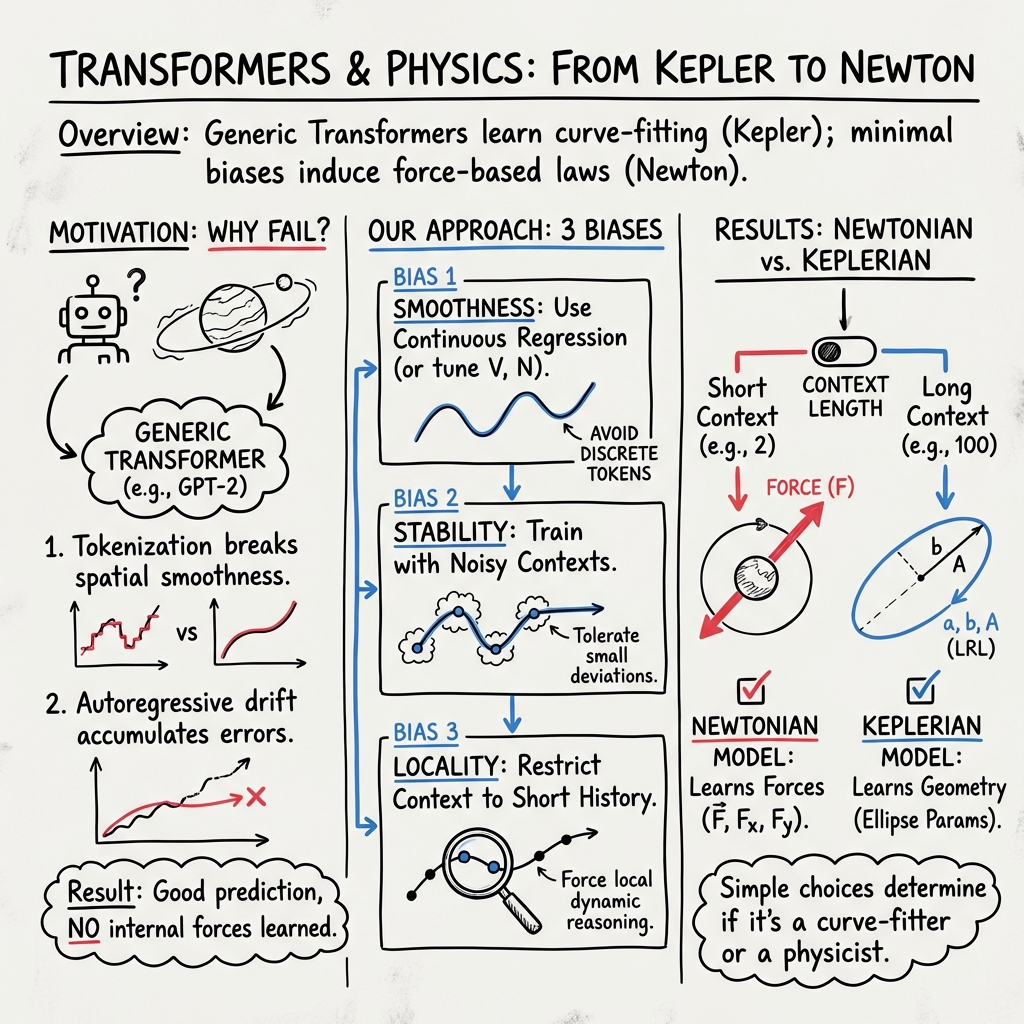

Abstract: Can general-purpose AI architectures go beyond prediction to discover the physical laws governing the universe? True intelligence relies on "world models" -- causal abstractions that allow an agent to not only predict future states but understand the underlying governing dynamics. While previous "AI Physicist" approaches have successfully recovered such laws, they typically rely on strong, domain-specific priors that effectively "bake in" the physics. Conversely, Vafa et al. recently showed that generic Transformers fail to acquire these world models, achieving high predictive accuracy without capturing the underlying physical laws. We bridge this gap by systematically introducing three minimal inductive biases. We show that ensuring spatial smoothness (by formulating prediction as continuous regression) and stability (by training with noisy contexts to mitigate error accumulation) enables generic Transformers to surpass prior failures and learn a coherent Keplerian world model, successfully fitting ellipses to planetary trajectories. However, true physical insight requires a third bias: temporal locality. By restricting the attention window to the immediate past -- imposing the simple assumption that future states depend only on the local state rather than a complex history -- we force the model to abandon curve-fitting and discover Newtonian force representations. Our results demonstrate that simple architectural choices determine whether an AI becomes a curve-fitter or a physicist, marking a critical step toward automated scientific discovery.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

From Kepler to Newton: How simple design choices help Transformers learn real physics

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper asks a big question: Can today’s AI models learn not just to predict what happens next, but also discover the simple rules that make the world work? The authors study this in a clean, controlled setting: predicting how a planet moves around the sun. They show that small, general “nudges” in how we build and train Transformers can make the difference between an AI that just connects the dots on a curve (like Kepler’s ellipse fits) and an AI that learns real causes and laws (like Newton’s forces and F = ma).

The main question in simple terms

- Why do standard Transformers predict planetary motion well but fail to learn the actual physical law of gravity?

- What small design choices (called inductive biases) can push them to learn the true, simple rules behind the motion?

“Inductive bias” just means building in gentle hints about how the world usually works. Think of it as setting up good habits for the model, like keeping nearby points in space similar, practicing with imperfect inputs, or focusing on the most recent steps.

What did they try? (Methods, with simple analogies)

The team tested three ideas while training Transformers to predict a planet’s next position from its past positions:

1) Spatial smoothness: Keep space “smooth” instead of choppy

- Problem: If you chop continuous coordinates (like x, y) into many discrete “bins” (tokens), two points that are very close in space can look completely unrelated to the model. It’s like drawing a map using only square tiles and forgetting that neighboring tiles are neighbors unless you relearn it from scratch.

- What they did:

- They measured how well the model’s learned “map” of space matched real coordinates (using a simple “linear probe,” which checks if a straight line in the model’s internal space can predict x or y).

- They showed that discretizing space into too many tokens breaks spatial smoothness and makes learning the true geometry hard.

- They either:

- Reduced the number of bins (coarser tokenization), or

- Skipped tokenization and fed real-number coordinates directly.

Analogy: If your ruler has too many wobbly marks, measuring distances becomes noisy. Fewer, clearer marks—or a smooth tape—work better.

2) Spatial stability: Train the model to handle small mistakes

- Problem: When predicting step by step with real-number outputs (regression), tiny errors can snowball. After many steps, the planet can “spiral” into the sun or fly off into space in the prediction.

- What they did:

- During training, they deliberately added small, random noise to the past inputs (called “noisy context learning”). It’s like practicing a piano piece with slight distractions so that, during the performance, you’re robust to surprises.

- With this trick, the regression models (using continuous coordinates and mean squared error) became much more stable and, when tuned well, beat the classification models (using tokens and cross-entropy) across data sizes.

3) Temporal locality: Focus on the immediate past

- Key idea: In Newtonian physics, the next state depends mainly on the current and just-previous states (because F = ma is a second-order rule). You don’t need a long history.

- What they did:

- They controlled how much history the Transformer could see (“context length”).

- With a short context (just the last 2 steps), the model learned to compute forces—like a Newtonian physicist.

- With a long context (many past steps), the model preferred to fit an ellipse from all points—like Kepler’s geometric approach.

Analogy: If you drive by looking only at the road right in front of you and your current speed, you learn to react to local conditions (Newton). If you drive by memorizing the entire route behind you, you’re just extending a pattern (Kepler-style curve fitting).

What did they find? (Key results and why they matter)

- Spatial smoothness matters:

- Heavy tokenization (lots of bins) makes neighboring places look unrelated, so the model struggles to build a good “mental map” of space.

- Solutions:

- Use fewer bins if you tokenize, or

- Better yet, give the model continuous coordinates so smoothness is built in.

- More data helps, but there are diminishing returns; simply making embeddings bigger didn’t fix the map problem past a small threshold.

- Spatial stability is fixable:

- Regression models initially fail from error build-up.

- Training with “noisy contexts” makes them robust.

- With this fix, regression models consistently outperform classification models when tuned properly.

- Temporal locality flips the model from Kepler to Newton:

- Long context → Keplerian world model: the Transformer internally encodes ellipse parameters and “continues the curve.”

- Short context (2 steps) → Newtonian world model: the Transformer internally encodes gravitational forces and follows F = ma.

- There’s a clear “phase change” controlled by context length.

- Note: Long context often gives slightly better raw prediction accuracy because curve-fitting is very robust, but it doesn’t mean the model understands the underlying cause.

Why this is important:

- It shows the difference between being a great predictor and truly understanding the rules. The Keplerian model can predict well but doesn’t know about forces; the Newtonian model captures the cause-and-effect law, which is more likely to generalize to new, unfamiliar situations.

So what? (Implications and impact)

- Small, general design choices can steer AI from being a “curve-fitter” to being a “scientist”:

- Keep space smooth (use continuous inputs or careful tokenization).

- Make training robust (practice with noisy past inputs).

- Keep time local (limit attention to the recent steps so simple laws are favored).

- This is a step toward “AI Scientists” that discover real laws from data, not just patterns in the data.

- It also refines what we mean by a “world model”: not just being able to predict, but also representing the actual mechanisms (like forces) that cause the predictions—so models can handle new, out-of-distribution scenarios better.

A quick recap of the takeaways

- Without the right hints, Transformers can predict well but miss the physics.

- Add three minimal biases—spatial smoothness, spatial stability, and temporal locality—and they can learn Newton’s laws.

- Simple architecture and training choices decide whether an AI learns “what happens next” or “why it happens.”

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to guide future research:

- External validity beyond idealized two-body Keplerian orbits: no tests on multi-body (n-body) systems, perturbations, non-inverse-square forces, non-conservative forces, or hyperbolic/unbound trajectories.

- Dimensionality limits: all experiments are in 2D; it’s unknown whether the proposed inductive biases and findings hold in full 3D orbital mechanics or under coordinate-frame changes.

- Realism of data: no evaluation on noisy, irregularly sampled, missing-observation, or real astronomical datasets; robustness to measurement errors and sensor noise remains untested.

- Time-step generalization: models are trained and tested at a single fixed Δt; OOD generalization to different sampling intervals or variable time steps is not assessed.

- Physical invariances: invariance/equivariance to rotations, translations, and scalings is not enforced or measured; it is unclear if learned “Newtonian” representations are coordinate-agnostic.

- Conservation laws: long-horizon rollouts are not evaluated for conservation of energy and angular momentum; whether the “Newtonian” internal representations induce physically consistent trajectories is unknown.

- Keplerian–Newtonian “phase transition”: the empirical transition with context length lacks a theoretical explanation; the roles of positional encodings, attention span, and training curricula are not analyzed.

- Combining locality with predictive robustness: large contexts improve accuracy (Keplerian) while short contexts yield mechanistic locality (Newtonian); how to architect models that achieve both simultaneously remains open.

- Automatic discovery of laws: reliance on linear probes provides only implicit evidence; there is no mechanism to autonomously extract explicit symbolic laws (e.g., F = ma) from latent states.

- Probe dependence and causality: linear R² scores may reflect correlational features; causal tests (e.g., ablations, counterfactuals, interventions) to verify that internal features are used mechanistically are absent.

- Generality of the “spatial smoothness” scaling law: derived on a 1D sine-wave toy problem; it is unclear if the D–V–N scaling law and critical embedding dimension extend to 2D/3D or richer dynamics.

- Tokenization vs. regression beyond Kepler: the conclusion that continuous regression with noisy contexts outperforms classification is shown only on Kepler-like data; applicability to other continuous-control or physical systems is untested.

- Noise-injection schedule: the effectiveness of “noisy context learning” depends on a hand-tuned noise scale; principled or adaptive schedules and their impact on stability and generalization are not explored.

- Training objectives: only next-step prediction with MSE or cross-entropy is studied; multi-step rollout losses, stability-aware objectives, scheduled sampling, or DAgger-like methods are not compared.

- Architectural scope: results are shown for GPT-2–style transformers; whether similar inductive biases induce Newtonian models in alternative sequence models (state-space models, RNNs, equivariant GNNs) is unknown.

- Positional encoding effects: the influence of absolute vs. relative/rotary time encodings on locality, stability, and the Keplerian–Newtonian transition is not examined.

- Capacity and scale sensitivity: some analyses use small models/datasets; reproducibility of the findings at larger model scales and with diverse hyperparameters (layers, heads, width) requires verification.

- Hyperparameter selection for tokenization: while smaller vocabularies aid spatial map emergence, there is no principled procedure to choose V that balances resolution against embedding locality, nor analysis of edge-bin artifacts.

- Emergence vs. enforcement of locality: truncating context enforces locality externally; whether models can learn to ignore long-range context when allowed (e.g., via regularizers or attention masks) is not tested.

- Curriculum strategies: the impact of curricula that gradually reduce context length or noise, or that alternate between local and global tasks, on inducing mechanistic representations is unexplored.

- Integrator fidelity: the model appears to imitate forward Euler-like updates; whether it can learn or benefit from symplectic or higher-order integrator inductive biases is not investigated.

- Distributional coverage: sensitivity to the training distribution over eccentricity, semi-major axis, and orientations is not analyzed; robustness to OOD values (e.g., e > 0.8) is unknown.

- Unit and scale sensitivity: the effect of coordinate/unit scaling on regression stability and learned representations (with or without normalization/standardization) is not reported.

- Latent computation mechanisms: beyond linear probes, mechanistic interpretability (e.g., circuits, attention patterns, head roles) is not performed to show how forces or orbit parameters are computed internally.

- Interaction of biases: the joint effects and trade-offs among spatial smoothness, spatial stability, and temporal locality are not systematically mapped (e.g., Pareto frontiers over prediction error vs. mechanistic fidelity).

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete, deployable applications and workflows that leverage the paper’s findings on spatial smoothness, spatial stability (noisy context learning), and temporal locality (short attention windows), along with associated sectors and feasibility notes.

- Mechanistic time-series modeling protocol for continuous variables (software, robotics, energy, healthcare)

- Use continuous inputs (avoid discretization), train with regression (MSE), and inject noise into past inputs during training to mitigate error accumulation in autoregressive inference.

- Workflow: continuous coordinate ingestion → regression objective → noisy context training (tune noise σ to a sweet spot) → validation on long-horizon rollouts.

- Tools: time-series libraries (PyTorch/TF) with “noisy context” training hooks; model cards documenting σ and long-horizon robustness.

- Assumptions/dependencies: dynamics must be reasonably local and smooth; requires careful σ tuning and sufficiently frequent sampling (small Δt) to keep local updates valid.

- Context-window tuning to induce mechanistic vs curve-fitting behavior (software, robotics, forecasting)

- Restrict attention to the immediate past (context length ≈2–4) when the goal is to learn local causal dynamics (Newtonian-like); allow long contexts when geometric curve-fitting (Keplerian-like) suffices or improves accuracy/robustness in noisy settings.

- Tools: configurable attention window schedulers in transformer time-series models; training policies that swap window sizes by task.

- Assumptions/dependencies: locality must hold at the chosen Δt; shortening context can reduce raw predictive accuracy on long horizons and non-local phenomena.

- Tokenization guidance for continuous signals (ML engineering across sectors)

- Prefer continuous coordinates over discretization for spatial smoothness. If discretization is unavoidable, reduce vocabulary size and ensure adequate data coverage to enable an emergent spatial map; don’t rely on large embedding dimensions alone.

- Tools: quantization/tokenezation utilities that optimize vocabulary size V relative to data size D; monitoring R² of linear probes on embeddings to audit spatial map quality.

- Assumptions/dependencies: the scaling relation shows D must grow at least as fast as V; overly coarse V reduces resolution while overly large V damages spatial locality without massive data.

- World-model diagnostics via linear probing (academia, industry QA, policy audit)

- Apply linear probes to latent states to assess whether a model encodes force variables (Fx, Fy, |F|) or global orbital parameters (a, b, LRL vector A), thereby determining if it learned a Newtonian (local) or Keplerian (global) world model.

- Tools: probing suite reporting layer-wise R², dashboards labeling model behavior as “mechanistic” or “curve-fitting.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: requires prior knowledge of target variables to probe; probes provide implicit evidence rather than explicit symbolic laws.

- Robust satellite and orbital trajectory prediction (aerospace)

- Use the regression+noisy context protocol with appropriately short context windows to simulate local dynamics of satellites in near two-body regimes; switch to longer context when orbital geometry fitting is preferable (e.g., noisy telemetry).

- Tools: space-ops prediction modules with configurable locality; model audits to confirm Newtonian representations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: two-body approximations; multi-body and perturbations (drag, J2 effects) reduce locality and require extensions.

- Safer robot dynamics modeling and control (robotics)

- Train local dynamics models with short contexts to capture causal updates (forces/accelerations), improving interpretability and potential OOD behavior; inject input noise for rollout robustness.

- Tools: robot learning stacks (e.g., sim-to-real pipelines) with locality constraints; “mechanistic mode” toggles.

- Assumptions/dependencies: robot/environment dynamics must be reasonably local at the control frequency; some tasks need longer memory (contacts/friction history).

- Grid load and industrial process forecasting with stability safeguards (energy, manufacturing)

- Adopt noisy context training to improve long-horizon stability in autoregressive regressors; selectively restrict context when causal local models are beneficial.

- Tools: MLOps templates for continuous signal forecasters with σ-tuning; monitoring drift/error accumulation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: locality varies by process; longer contexts may still be needed for regime shifts or calendar effects.

- Vital sign and patient state forecasting with reduced compounding error (healthcare)

- Continuous regressors with input noise to resist error explosions; short contexts to model local physiological dynamics when appropriate, and longer contexts for chronic trends.

- Tools: clinical time-series libraries with noise-injection training; audits for mechanistic encoding of rate-of-change variables.

- Assumptions/dependencies: clinical deployment needs rigorous validation and regulatory compliance; some conditions are non-local or event-driven.

- Education and communication tools illustrating “curve-fitting vs causal laws” (education, daily life)

- Interactive apps demonstrating how context length flips a model from Keplerian curve-fitting to Newtonian force computation; teaching the importance of inductive biases in AI.

- Tools: classroom simulators, coding notebooks with adjustable context windows and noise levels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: synthetic examples generalize pedagogically; not a replacement for formal physics instruction.

- Practical model selection guidance for time-series teams (software engineering)

- Establish decision rules: if interpretability and OOD behavior are priorities, prefer short-context mechanistic training; if maximum accuracy on in-distribution noisy data is needed, use longer contexts for global fits.

- Tools: model-selection playbooks; checklists balancing accuracy vs mechanism and OOD goals.

- Assumptions/dependencies: task requirements must be explicit; trade-offs are data- and domain-dependent.

Long-Term Applications

Below are forward-looking applications that require further research, scaling, or development to become reliable and broadly deployable.

- AI Scientist systems with automated law extraction (academia, software, scientific discovery)

- Augment transformers with interpreter/symbolic regression heads to autonomously discover and output compact laws (e.g., F=ma), not just implicit representations.

- Tools: hybrid neural–symbolic pipelines, sparsity and symmetry priors, search over latent linear relations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust discovery across noisy, high-dimensional, non-ideal data; reliable detection of relevant variables without human hints.

- Regulatory “world-model audits” for safety-critical AI (policy, healthcare, transportation, energy)

- Standards requiring evidence of mechanistic encoding for systems making consequential predictions (e.g., model must demonstrate local causal representations under short contexts).

- Tools: certification protocols using probing, stress tests with controlled context windows and noise; compliance reporting.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consensus on what constitutes sufficient mechanistic evidence; sector-specific guidelines and liability frameworks.

- Adaptive context schedulers that toggle locality on-the-fly (software, robotics, forecasting)

- Architectures that dynamically adjust attention window length depending on regime (local causal vs global geometric trends), possibly guided by uncertainty or drift detectors.

- Tools: controllers for context length, multi-expert models (mechanistic and geometric experts) with gating.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable regime detection; seamless switching without instability or performance cliffs.

- General-purpose causal world models across domains (materials, climate, biology)

- Apply locality-inducing inductive biases to uncover governing mechanisms in complex systems (e.g., reaction kinetics, diffusion, ecological interactions).

- Tools: domain-tailored variables and Δt selection; integration with experimental pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: existence of local causal laws at the chosen temporal/spatial scales; careful variable selection and observability.

- OOD generalization via mechanistic latent spaces (software, robotics, finance)

- Leverage short-context training to build models that maintain performance on out-of-distribution scenarios by relying on invariant local rules rather than memorized histories.

- Tools: OOD benchmarks that separate “grey elephant” vs “pink elephant” regimes; regularizers emphasizing causal invariants.

- Assumptions/dependencies: tasks truly have stable local invariants; some domains (e.g., financial markets) exhibit non-stationary, strategic behavior limiting locality.

- Data-driven digital twins with interpretable dynamics (manufacturing, energy, infrastructure)

- Construct twins whose internal states encode forces or rates, enabling diagnosis, control, and compliance explanations.

- Tools: twin platforms with mechanistic probes; dashboards mapping latent force variables to physical components.

- Assumptions/dependencies: adequate sensing and data quality; mapping from latent to actionable controls.

- Foundation model redesigns for continuous signals (ML research, software)

- Architectures and training curricula that natively support continuous regression, stability via noisy contexts, and locality constraints—reducing reliance on discretization.

- Tools: transformer variants with built-in stability modules, continuous tokenizers, physics-aware positional encodings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: scalability to large multimodal settings; careful interaction with tasks needing long-range memory (language, documents).

- Educational platforms for scientific reasoning with AI (education)

- Curricula and labs where students use locality-inducing models to rediscover laws across physics, chemistry, and biology, fostering causal thinking.

- Tools: cross-domain datasets, explainable AI modules, symbolic extractors for discovered rules.

- Assumptions/dependencies: accessible tooling and datasets; alignment with educational standards.

- Sector-specific law-discovery assistants (materials design, biotech)

- Assist scientists in proposing candidate mechanisms from time-series data, ranking plausible laws, and suggesting experiments to disambiguate.

- Tools: hypothesis generators, active learning loops, symbolic regression with domain constraints.

- Assumptions/dependencies: integration with lab workflows; validation via controlled experiments.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Locality and smoothness must be valid at the chosen sampling resolution (Δt); some phenomena are inherently non-local or require multi-scale modeling.

- Linear probing demonstrates implicit knowledge, not explicit symbolic laws; full law extraction needs additional modules.

- Restricting context windows can trade off raw accuracy for mechanistic insight; teams must balance interpretability, OOD robustness, and in-distribution performance.

- Tokenization choices materially affect learning in continuous domains; reducing vocabulary size or using continuous inputs requires sufficient data coverage and stable training.

- Noisy context learning improves robustness but needs careful σ tuning to avoid overwhelming the learning signal.

Glossary

- auto-regressive: A modeling approach where each next output is generated conditioned on previous outputs or states. "in an auto-regressive manner,"

- Context length: The number of past tokens or states a transformer attends to for making its next prediction. "The context length controls the world model learned by transformers."

- Eccentricity: A scalar parameter e that measures how much an orbital ellipse deviates from circularity. "eccentricity e € [0.0, 0.8]"

- Forward Euler: A first-order numerical integration method for advancing solutions of differential equations in time. "forward Euler"

- Gravitational equation of motion: The second-order differential equation describing acceleration under gravity for orbital motion. "by numerically integrating the gravitational equation of motion,"

- Gravitational force magnitude: The absolute value of gravitational force, proportional to GM/r² in two-body dynamics. "Gravitational force magnitude | F | = GM/r2."

- Gravitational force x-component: The x-direction component of the gravitational force vector acting on a body. "Gravitational force x-component Fx = - GMx/r3."

- Gravitational force y-component: The y-direction component of the gravitational force vector acting on a body. "Gravitational force y-component Fy = - GMy/r3."

- Gravitational parameter: The product GM (gravitational constant times central mass) that sets orbital dynamics. "GM = 1.0 is the gravitational parameter."

- Harmonic oscillator: A dynamical system with sinusoidal solutions, often used as a simplified model of oscillatory motion. "A 1D harmonic oscillator has sine-wave solutions"

- Kepler dataset: A synthetic benchmark of idealized 2D planetary orbits used to test model predictions. "The Kepler dataset consists of 2D elliptical orbits of a planet around a central body (the sun) fixed at the origin."

- Kepler's first law: The rule that planetary orbits are ellipses with the Sun at one focus. "Kepler's first law"

- Keplerian world model: A global, geometry-based approach that fits ellipses to past trajectories to predict future states. "We refer to this global geometric approach as Keplerian world model"

- Laplace-Runge-Lenz vector: A conserved vector in Keplerian motion that encodes the ellipse’s orientation and eccentricity, pointing toward perihelion. "Laplace-Runge-Lenz vector A = (Ax, Ay)."

- Linear probing: An interpretability technique that fits linear readouts to internal representations to test if variables are linearly encoded. "We apply linear probing to search for linear directions in the model's latent representations"

- Mean distance error: An evaluation metric averaging Euclidean distance between predicted and true positions over generated steps. "The evaluation metric is the mean distance error"

- Newtonian world model: A local, force-based approach that computes gravitational forces from recent states and simulates the governing differential equations. "a Newtonian world model would compute gravitational forces"

- Newton's second law: The fundamental relation F = ma linking force, mass, and acceleration. "Newton's second law"

- Noisy context learning: A training strategy that injects noise into past inputs to improve robustness and mitigate error accumulation. "a strategy known as noisy context learning (Ren et al., 2025)"

- Perihelion: The orbital point where a planet is closest to the Sun. "initialize the system at perihelion (closest approach)"

- Phase transition: A sharp shift in model behavior (e.g., from Newtonian to Keplerian representations) triggered by changing a control parameter. "There is a phase transition between Keplerian and Newtonian models by varying context lengths"

- R2 (coefficient of determination): A statistic indicating how well a model or linear direction explains variance in target variables. "Linear probing R2 score"

- Residual merging: The operation in transformer blocks where residual connections are combined with current activations. "both before and after residual merging"

- Scaling law: A quantitative relation describing how performance metrics scale with variables like data size or vocabulary. "1 - R2 obeys a scaling law with respect to vocabulary size V and training tokens D."

- Semi-major axis: The longest radius of an elliptical orbit, denoted a. "semi-major axis a € [0.5, 2.0]"

- Semi-minor axis: The shortest radius of an elliptical orbit, denoted b. "semi-minor axis b"

- solve_ivp: A SciPy routine for solving initial value problems for ordinary differential equations. "We integrate the system using solve_ivp in scipy"

- Spatial smoothness: An inductive bias ensuring nearby spatial coordinates are represented continuously rather than as unrelated tokens. "Inductive bias 1: spatial smoothness."

- Spatial stability: An inductive bias addressing rapid error accumulation in continuous autoregressive predictions. "Inductive bias 2: spatial stability."

- Temporal locality: The assumption that the next state depends only on the immediate past (current and previous states), not long histories. "Inductive bias 3: temporal locality."

- World model: An internal causal abstraction that captures governing dynamics beyond mere next-step prediction. "do world models truly emerge within foundation models?"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.