OAT: Ordered Action Tokenization

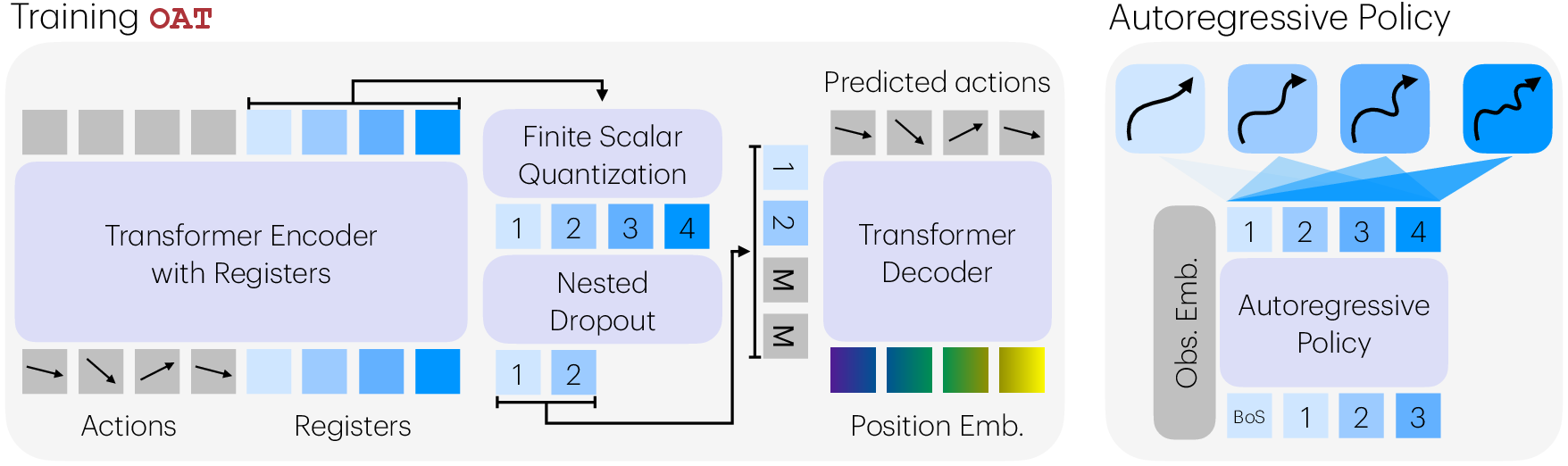

Abstract: Autoregressive policies offer a compelling foundation for scalable robot learning by enabling discrete abstraction, token-level reasoning, and flexible inference. However, applying autoregressive modeling to continuous robot actions requires an effective action tokenization scheme. Existing approaches either rely on analytical discretization methods that produce prohibitively long token sequences, or learned latent tokenizers that lack structure, limiting their compatibility with next-token prediction. In this work, we identify three desiderata for action tokenization - high compression, total decodability, and a left-to-right causally ordered token space - and introduce Ordered Action Tokenization (OAT), a learned action tokenizer that satisfies all three. OAT discretizes action chunks into an ordered sequence of tokens using transformer with registers, finite scalar quantization, and ordering-inducing training mechanisms. The resulting token space aligns naturally with autoregressive generation and enables prefix-based detokenization, yielding an anytime trade-off between inference cost and action fidelity. Across more than 20 tasks spanning four simulation benchmarks and real-world settings, autoregressive policies equipped with OAT consistently outperform prior tokenization schemes and diffusion-based baselines, while offering significantly greater flexibility at inference time.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper is about teaching robots to plan and move using the same kind of step‑by‑step “next token” thinking that powers modern LLMs. The challenge: robot motions are smooth numbers (continuous), but next‑token models like to work with small, discrete symbols (tokens). The authors introduce a new way to turn robot motions into a short, well‑organized list of tokens so that a robot can generate actions one token at a time, quickly and reliably.

They call their method Ordered Action Tokenization, or OAT (also referred to as Maroon in the paper).

What questions did the researchers ask?

They focused on a simple set of questions:

- How can we compress a robot’s future movements into just a few tokens, without losing important details?

- How can we make sure any sequence of tokens a robot produces can always be turned back into a valid, executable motion (no “nonsense” outputs)?

- How can we arrange the tokens so that making them from left to right (one after another) naturally goes from “rough plan” to “fine details,” matching how autoregressive (next‑token) models think?

How did they do it?

The authors designed a tokenizer (a translator between motions and tokens) that creates a short, ordered list of tokens for each chunk of robot actions.

Here’s the idea in everyday language:

- The problem: Robots move in continuous ways (like smoothly moving a hand), but next‑token models want discrete symbols. If you try the simplest approach (breaking each number into bins), you get way too many tokens and it’s slow. Other methods either create tokens that are hard to use step‑by‑step or can sometimes decode into invalid motions.

- The three “must‑haves” for a good action tokenizer: 1) High compression: Pack a lot of motion information into just a few tokens (like summarizing a paragraph into a couple of key words). 2) Total decodability: Any token sequence should always decode into a valid motion (no dead ends, no crashes). 3) Left‑to‑right ordering: Earlier tokens should capture the big picture of the motion, and later tokens should add details. This fits how next‑token models generate outputs.

- Their solution: OAT (Maroon)

- Transformer with register tokens: Imagine a set of special “sticky notes” that collect the most important parts of the motion. A transformer (a kind of neural network) reads the action sequence and writes a compact summary onto these notes.

- FSQ (finite scalar quantization): This turns each summary value into one of a few fixed levels—like turning a smooth volume knob into a few distinct clicks. This produces discrete tokens.

- Nested dropout (to create order): During training, the decoder often only sees the first few tokens and has to reconstruct the motion anyway. This forces the system to put the most important info in the earliest tokens and add refinements in later ones—like a drawing that starts as a rough sketch and gets sharper as you add strokes.

- Causal attention (to keep direction): Later “sticky notes” can look at earlier ones, but not the other way around. This encourages a left‑to‑right dependence that matches next‑token generation.

- Prefix decoding (anytime use): Because the tokens are ordered from coarse to fine, you can stop early and still decode a valid motion. More tokens = more detail; fewer tokens = faster but coarser action. Think of a photo that first loads blurry and then sharpens.

They evaluate this approach inside an autoregressive policy: the robot observes the world, generates tokens one by one, and decodes them into a short action chunk (several steps of motion) to execute before planning again.

What did they find?

Across more than 20 simulated tasks (from popular robot benchmarks) and two real‑world tabletop tasks, the authors report:

- Higher success rates than previous tokenization methods and even strong diffusion‑based baselines, when using OAT with its ordered tokens.

- Faster and more flexible control: OAT can act with just a few tokens (low delay) and improve performance by adding more tokens when time allows.

- Clear benefits from ordering: If they remove the ordering tricks (like nested dropout), performance drops. This shows the left‑to‑right structure really matters for next‑token policies.

- Good compression without breaking decoding: Unlike some methods that risk producing invalid token sequences, OAT always decodes to a valid motion, which is safer for real robots.

- Sensible trade‑offs: A moderate token vocabulary size works best. Too small loses detail; too large makes prediction harder. Choosing a reasonable number of tokens and action‑chunk length balances speed, stability, and accuracy.

Why this is important: It shows that the way you “tokenize” actions can make or break a robot’s ability to plan step‑by‑step like a LLM. OAT gives robots a practical, reliable action “language.”

What does this mean going forward?

- Smarter, faster robot control: Robots can plan actions the way chatbots predict words—left to right—while keeping delays low. They can act “anytime”: give a quick answer when rushed, add details when there’s time.

- Safer deployment: Since any token sequence decodes to a valid motion, there’s less risk of a robot producing nonsense that can’t be executed.

- Scales with bigger models and data: OAT’s ordered tokens fit naturally with large autoregressive models, which could help robots generalize to new tasks.

- Practical for the real world: The method worked not only in simulations but also on real manipulation tasks, suggesting it can help robots in homes, labs, and factories.

In short, the paper shows that giving robot actions an ordered, compact “alphabet” lets next‑token models plan movements more effectively—starting with a rough plan and refining it as needed—making robot learning both efficient and reliable.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, actionable list of the paper’s unresolved knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that future work could address.

- Clarify and formalize the theoretical guarantees of token ordering: provide proofs or bounds showing when nested dropout + causal register attention yield a provably ordered latent code and monotonic prefix improvements in reconstruction/performance.

- Develop adaptive policies for prefix length K: devise principled stopping criteria (e.g., uncertainty, entropy, value estimates, or task-level success predictors) to choose K online under latency constraints, rather than using fixed K.

- Safety and constraint satisfaction: ensure decoded action chunks always respect robot kinematics, joint/velocity limits, collision avoidance, and dynamic feasibility; explore constraint-aware decoding or projection.

- Robustness to token errors: characterize how detokenization degrades with token corruptions (Hamming distance, adversarial tokens) and add error-correcting schemes or confidence-aware detokenization to mitigate catastrophic actions.

- Token semantics and interpretability: quantify what each ordered token captures (e.g., coarse trajectory shape vs. fine contact timing), including mutual information per token and whether tokens align with human-interpretable primitives for planning.

- Generalization and OOD robustness: evaluate performance under domain shifts (new objects, layouts, lighting), partial occlusion, sensor noise, and unseen tasks; analyze whether ordered tokens confer robustness advantages over baselines.

- Scaling laws and data efficiency: study how performance scales with model size, dataset size, and token horizon; measure sample efficiency relative to diffusion/flow and other learned tokenizers.

- Extremely long horizons and variable durations: test horizons beyond H_a=64 and support variable-length action chunks; investigate asynchronous control where chunk duration is adapted online.

- Multi-modal conditioning and language: assess integration with instruction-following VLA systems (language, audio, haptics), and whether ordered action tokens improve grounding and multi-modal reasoning.

- Multi-task and cross-task learning: quantify whether a single tokenizer trained across tasks generalizes better than task-specific tokenizers; measure transfer to new tasks without retraining the tokenizer.

- Comparison across quantizers: directly compare FSQ with VQ/VQ-VAE variants and residual quantization in terms of code utilization, stability, dead-code prevalence, and downstream policy perplexity.

- Codebook management: design criteria for choosing FSQ level configurations; add entropy/usage regularization to prevent overly sparse codebooks that degrade autoregressive modelability.

- Ablate causal attention separately: isolate the contribution of causal register-register attention vs. nested dropout to ordering and policy performance, including mixed or alternative masking strategies.

- Decoder objectives beyond MSE: evaluate control-aware losses (e.g., smoothness, jerk, dynamic constraints), task success proxies, or learned perceptual/action metrics tailored to manipulation.

- Real-time edge deployment: measure end-to-end control loop latency on embedded hardware (e.g., Jetson, CPU), including detokenizer cost; investigate lightweight architectures or quantized models for on-board deployment.

- Early-token safety guarantees: ensure that short-prefix decodings are not only “valid” but also safe and executable; add conservative priors or safety filters for coarse actions when acting anytime.

- Policy sampling strategies: analyze the impact of next-token sampling temperature, beam search, top-k/top-p, and guidance on control stability; provide best practices for autoregressive action generation.

- Fair, budget-aligned baselines: compare against diffusion/flow models under matched latency budgets (e.g., limit sampling steps) and include modern flow/diffusion SOTA to strengthen claims about efficiency-performance trade-offs.

- Observation horizon and memory: study sensitivity to H_o and richer temporal observation histories; analyze whether longer observation windows change the optimal action/token horizons.

- Re-inference scheduling: explore policies for how many actions to execute per chunk (not only half of H_a), and adaptive re-inference schedules tied to confidence or environment change.

- Diverse action spaces: extend beyond 7D end-effector control to torque-level, hybrid discrete-continuous actions (e.g., tool modes), and constrained motion primitives; test deformable objects, non-prehensile, and contact-rich manipulation.

- Mobile and dexterous platforms: evaluate on mobile manipulation, dual-arm/bimanual tasks, and dexterous hands, including contact transitions and complex coordination.

- Failure case analysis: document tasks where OAT underperforms diffusion or QueST; analyze error modes (e.g., high-frequency contact timing, force-sensitive phases) and propose targeted remedies.

- Token-frequency imbalance: measure token distribution skew and its effect on autoregressive training; add reweighting or curriculum to balance rare-but-critical fine-detail tokens.

- Continual and incremental learning: investigate updating the tokenizer with new data without catastrophic forgetting and maintaining compatibility with previously trained policies.

- Planning integration: test whether coarse-to-fine tokens can act as a bridge to hierarchical planners (e.g., planning on early tokens, refinement on later tokens), including closed-loop replanning.

- Monotonicity guarantees at execution: quantify how often more tokens harm performance (negative refinements) and design mechanisms to detect and prevent detrimental refinements.

- Dataset transparency: clarify whether tokenizers are trained per-task or multi-task; provide statistics on demonstrations per task and analyze how data imbalance affects tokenizer learning.

- Mask token design: study different mask embeddings, training distributions p(K), and their impact on prefix decoding generalization; explore soft masks or learned conditional priors for tails.

- Smoothness and temporal consistency: add regularizers to ensure decoded chunks are temporally smooth and compatible across chunk boundaries during receding-horizon execution.

- Open-source reproducibility: release full tokenizer and policy code, training scripts, and checkpoints to validate claims across independent labs and additional benchmarks.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The items below translate the paper’s findings and methods into concrete uses that can be deployed now, highlighting sectors, potential tools/products, and feasibility notes.

- [Robotics: Manufacturing and Warehousing] Low-latency, robust manipulation policies for assembly, kitting, and pick-and-place on edge hardware using ordered action tokenization (OAT) with prefix-based decoding to trade accuracy for speed on the fly.

- Tools/products/workflows: ROS 2/Isaac integration of an OAT detokenizer node; “anytime control” mode that selects prefix length K dynamically based on latency budget; token-level monitoring UI to visualize coarse-to-fine plans.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of task-specific demonstration data; action bounds and safety checks downstream of the detokenizer; compute/latency on the target controller may differ from A100 benchmarks.

- [Robotics: VLA Systems] Replace diffusion heads or naive binning with OAT as the discrete action head for Vision-Language-Action stacks to reduce latency, improve modelability, and enable graceful early-exit execution.

- Tools/products/workflows: Drop-in OAT “action head” for OpenVLA/RT-style stacks; API to pick K at inference; unit tests ensuring total decodability under arbitrary token sequences.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Minor training pipeline changes (register tokens, FSQ, nested dropout); proper tuning of horizons (e.g., H_a≈32, H_l≈8) and FSQ levels (≈512–1000 codebook size).

- [Robotics: Teleoperation and Shared Autonomy] Stable, low-latency assistance where coarse tokens execute immediately while finer tokens refine the motion if time allows (e.g., operator-in-the-loop bin picking or palletizing).

- Tools/products/workflows: Teleop stack with OAT-backed “progressive refinement” path; default fail-safe to execute K=1–2 in network hiccups; logging tokens for post-hoc analysis.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Calibrated detokenizer outputs (units, limits); fallback safety layer (action clamping, watchdogs).

- [Robotics: Mobile and Field Robots (Agriculture, Inspection)] Edge-friendly control under intermittent connectivity by transmitting/using short token prefixes that already decode into valid, safe actions.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Connectivity-aware” controller that adjusts K with bandwidth; token-compressed teleoperation logs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain data for training; terrain-/task-specific safety wrappers.

- [Healthcare: Logistics and Assistive Robots] Hospital delivery carts or assistive home robots benefit from robust, low-latency chunked actions with total decodability that reduces runtime failure modes.

- Tools/products/workflows: OAT-enabled assistive manipulation primitives (grasping, door handling) with early-exit modes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory constraints require additional safety validation; action-space limits must reflect clinical safety thresholds.

- [Software/Tools] Standardized tokenization/detokenization libraries and inference services for continuous control.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- A “oat-tokenizer” Python/ROS 2 package implementing registers, FSQ, and nested dropout.

- Inference microservice exposing detokenization with K-control, plus profiling hooks to choose K based on real-time latency.

- Assumptions/dependencies: GPU optional; must benchmark kernel performance for target devices; ensure reproducible training configs.

- [Data Engineering] Storage and streaming of manipulation datasets as discrete tokens for compression, faster I/O, and reproducible replay.

- Tools/products/workflows: Dataset conversion tool (actions↔tokens); token-based telemetry for fleet monitoring and analytics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Decoder versioning for reproducibility; privacy/compliance as needed.

- [Academia/Education] Teaching and research on scalable sequence models for control using a robust tokenizer that is aligned with next-token prediction and supports anytime decoding.

- Tools/products/workflows: Course labs comparing binning/FAST/learned-latents/OAT; ablation templates for H_a, H_l, and codebook size selection; visualization of coarse-to-fine trajectory reconstructions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to standard benchmarks (LIBERO, RoboMimic, MetaWorld, RoboCasa).

- [Operations/Policy-in-Org] Engineering guidelines for generative robot policies to mandate “total decodability” and “anytime execution” as resilience requirements.

- Tools/products/workflows: Internal checklists and CI tests that fuzz token sequences to verify decodability; SLOs coupling latency and prefix length.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Safety layer remains mandatory; total decodability ≠ guaranteed safety—combine with action constraints and monitors.

Long-Term Applications

These uses require further research, scaling, validation, or formalization before widespread deployment.

- [Robotics: Multi-Robot and Cross-Embodiment Control] A shared, ordered token vocabulary for action chunks enabling policy transfer and coordination across heterogeneous robots.

- Potential outcomes: “Control lingua franca” for fleet learning; cross-robot imitation via token sequences; inter-robot token streaming.

- Dependencies: Embodiment-agnostic action parameterizations; alignment layers per robot; large, diverse multi-embodiment datasets.

- [Safety-Critical Sectors: Surgical Robotics, Aviation, Autonomous Driving] Coarse-to-fine, anytime action generation under strict safety/regulatory constraints with formal guarantees on detokenization and runtime monitors.

- Potential outcomes: Certifiable, verifiable decoders; contract-based prefix execution with bounds on deviation from safe baselines.

- Dependencies: Formal verification of neural decoders or hybrid verified decoders; rigorous hazard analysis and standards compliance.

- [Energy and Buildings] Tokenized control for HVAC, smart grids, or microgrids where continuous control trajectories are generated autoregressively with adjustable compute budgets and bandwidth-aware streaming.

- Potential outcomes: Energy-aware “K-governor” to save power during noncritical periods; compressed control over constrained networks.

- Dependencies: Domain modeling and safe envelopes; integration with existing MPC/CBF-based safety layers.

- [Finance and Industrial Process Control] Adaptation of ordered tokenization to other continuous, sequential decision domains (e.g., algorithmic execution, chemical processes) where coarse-to-fine control may reduce latency or risk.

- Potential outcomes: Progressive strategy refinement where early tokens implement conservative actions and later tokens add precision.

- Dependencies: Careful mapping from domain actions to bounded, decodable spaces; regulatory oversight for financial systems.

- [Human-in-the-Loop Interactive Control] Mixed-initiative interfaces where users trigger early execution from coarse tokens and request refinements as needed (e.g., AR-guided manipulation, rehabilitation robots).

- Potential outcomes: “Scrubbable” action timelines where users visualize/edit token prefixes before execution.

- Dependencies: Usability studies; safe interruptibility and rollback mechanisms.

- [Standardization and Certification] Industry standards specifying properties like total decodability, prefix-decodability, and ordered token semantics for generative control stacks.

- Potential outcomes: Conformance test suites; procurement checklists for generative controllers; reference implementations.

- Dependencies: Multi-stakeholder alignment; empirical evidence across domains; open benchmarks and audits.

- [Hardware Acceleration] Specialized kernels or on-chip support for FSQ and register-based token pipelines to lower inference latency on microcontrollers and embedded GPUs.

- Potential outcomes: Deterministic, low-power OAT decoders; real-time prefix control on-cost hardware.

- Dependencies: Vendor cooperation; memory/throughput profiling; quantization-aware training.

- [RL and Online Learning] Use OAT as a compact, stable action representation for reinforcement learning, enabling better credit assignment and scalable model-based planning with token rollouts.

- Potential outcomes: Hybrid planners that search over ordered tokens; improved sample efficiency via structured action abstractions.

- Dependencies: Algorithmic advances integrating OAT with exploration, safety, and model-based components.

- [Formal Methods and Safety Tooling] Verified “total decodability” and runtime guards ensuring decoded actions remain within certified safe sets, even under arbitrary token sequences.

- Potential outcomes: Certificates attached to deployed decoders; automated counterexample generation and repair.

- Dependencies: Progress in verifying neural generators; compositional safety frameworks for control stacks.

Notes on Feasibility and Key Assumptions Across Applications

- Data and training: Quality and diversity of demonstration/control data are critical; domain shift must be managed (sim-to-real, new objects).

- Hyperparameters: Choosing action horizon H_a and latent horizon H_l matters; defaults near H_a≈32 and H_l≈8 were effective; excessively large codebooks can hurt autoregressive learning despite better reconstruction.

- Safety: “Total decodability” prevents undefined decoder failures but does not ensure safety; combine with action clamps, control barrier functions, and monitors.

- Performance on target hardware: Reported latencies are on A100; embedded controllers need profiling and possibly hardware-accelerated decoders.

- Integration: Requires wrapping OAT into existing middleware (ROS 2/Isaac) and aligning action spaces and units with robot controllers.

- Governance: For regulated domains, additional validation, logging, and auditing are necessary; standards work will lag technical feasibility.

Glossary

- Action chunk: A contiguous, multi-step segment of actions treated as a single unit for prediction or execution. "To enable autoregressive modeling, continuous action chunks must first be discretized into a sequence of tokens."

- Action tokenization: The process of mapping continuous control signals into sequences of discrete symbols for modeling. "This representation problem is known as action tokenization: the process of mapping continuous control signals into a sequence of discrete tokens."

- Autoregressive (policies): Models that generate outputs sequentially by conditioning each prediction on previously generated tokens. "Autoregressive policies offer a compelling foundation for scalable robot learning by enabling discrete abstraction, token-level reasoning, and flexible inference."

- Bottleneck representation: A compressed latent representation in an autoencoder that forces information to pass through a limited-capacity channel. "After encoding, the register tokens form the bottleneck representation of the autoencoder, while the encoded action tokens are discarded."

- Byte Pair Encoding (BPE): A data compression and subword tokenization method that merges frequent symbol pairs to form a compact vocabulary. "which employs the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) to decompose action chunks into frequency coefficients, followed by Byte Pair Encoding (BPE)."

- Causal attention: An attention mechanism that restricts information flow to past or current positions to enforce left-to-right generation. "Complementary to nested dropout, we impose a causal attention structure over the register tokens to further reinforce ordering."

- Causal ordering: A left-to-right structure over tokens where earlier tokens represent coarse information and later tokens refine details. "Causal Ordering, imposing a left-to-right structure over tokens that aligns with the inductive bias of next-token prediction."

- Codebook: The discrete set of quantization symbols available to represent latent vectors. "corresponding to an implicit codebook size ."

- Detokenization: The mapping from discrete token sequences back to continuous action trajectories. "A corresponding detokenization mapping maps token sequences back into continuous action space, producing executable action chunks."

- Diffusion policy (DP): A policy that generates actions via iterative denoising processes learned from data. "diffusion policy (DP)"

- Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT): A frequency-domain transform that represents sequences as sums of cosine functions, often used for compression. "which employs the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) to decompose action chunks into frequency coefficients"

- Finite scalar quantization (FSQ): A quantization scheme that discretizes continuous scalar latents into a finite set of levels. "OAT maps a chunk of continuous actions into an ordered sequence of discrete tokens using a transformer encoder with register tokens, FSQ, and nested dropout to induce token ordering."

- Flow-based policies: Generative models using invertible transformations to model complex distributions for action generation. "Diffusion and flow-based policies have proven highly effective for continuous action generation and imitation learning"

- Frequency-domain compression: Representing signals using frequency coefficients to achieve compactness and denoising properties. "analytical compression methods such as frequency-domain compression"

- Frequency-space Action Sequence Tokenization (FAST): A tokenization method that compresses actions using DCT and BPE in the frequency domain. "Frequency-space Action Sequence Tokenization (FAST)"

- Imitation learning: Learning policies by mimicking expert demonstrations rather than optimizing explicit reward signals. "have proven highly effective for continuous action generation and imitation learning"

- Latent space: The compressed, learned representation space in which high-dimensional data are mapped by an encoder. "learned tokenizers often produce unstructured latent spaces that are poorly aligned with next-token prediction"

- Learned latent tokenizer: A data-driven encoder-decoder that compresses actions into discrete latent tokens optimized end-to-end. "learned latent tokenizers that lack structure, limiting their compatibility with next-token prediction."

- Modelability: The ease with which generative models can learn and predict the distribution of a representation. "trade-off between compression rate, modelability under autoregressive learning, and decodability."

- Nested dropout: A training technique that randomly drops suffixes of a representation to enforce an ordered, prefix-robust encoding. "We train OAT to produce an ordered representation by applying nested dropout to the register tokens during training."

- Per-dimension binning (Bin): Discretizing each action dimension independently by assigning values to uniform bins. "The most commonly used action tokenization approach is per-dimension binning (Bin)"

- Prefix-based detokenization: The ability to decode valid, progressively refined actions from partial token prefixes. "Due to its ordered token space, OAT enables prefix-based detokenization: early tokens produce coarse action chunks, and additional autoregressive steps progressively refine actions, enabling flexible, anytime action generation."

- Quantized Skill Transformer (QueST): A learned latent tokenizer baseline that compresses actions via temporal downsampling and quantization. "We additionally compare against Quantized Skill Transformer (QueST), a representative learned latent tokenizer."

- Receding-horizon control: An execution scheme that repeatedly plans a horizon of actions but executes only an initial subset before replanning. "which reflects practical receding-horizon control"

- Register tokens: Learnable tokens in a transformer that aggregate and store information, acting as compact memory. "we concatenate the input action sequence with a fixed set of learnable register tokens, "

- Total decodability: A property where every possible token sequence maps to a valid output, ensuring the decoder is a total function. "Total Decodability, meaning the decoder is a total function in which every token sequence maps to a valid action chunk"

- Vector quantization: Discretizing continuous latent vectors by mapping them to the nearest entries in a finite codebook. "encoder-decoder architectures with vector quantization"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.