ShapeR: Robust Conditional 3D Shape Generation from Casual Captures

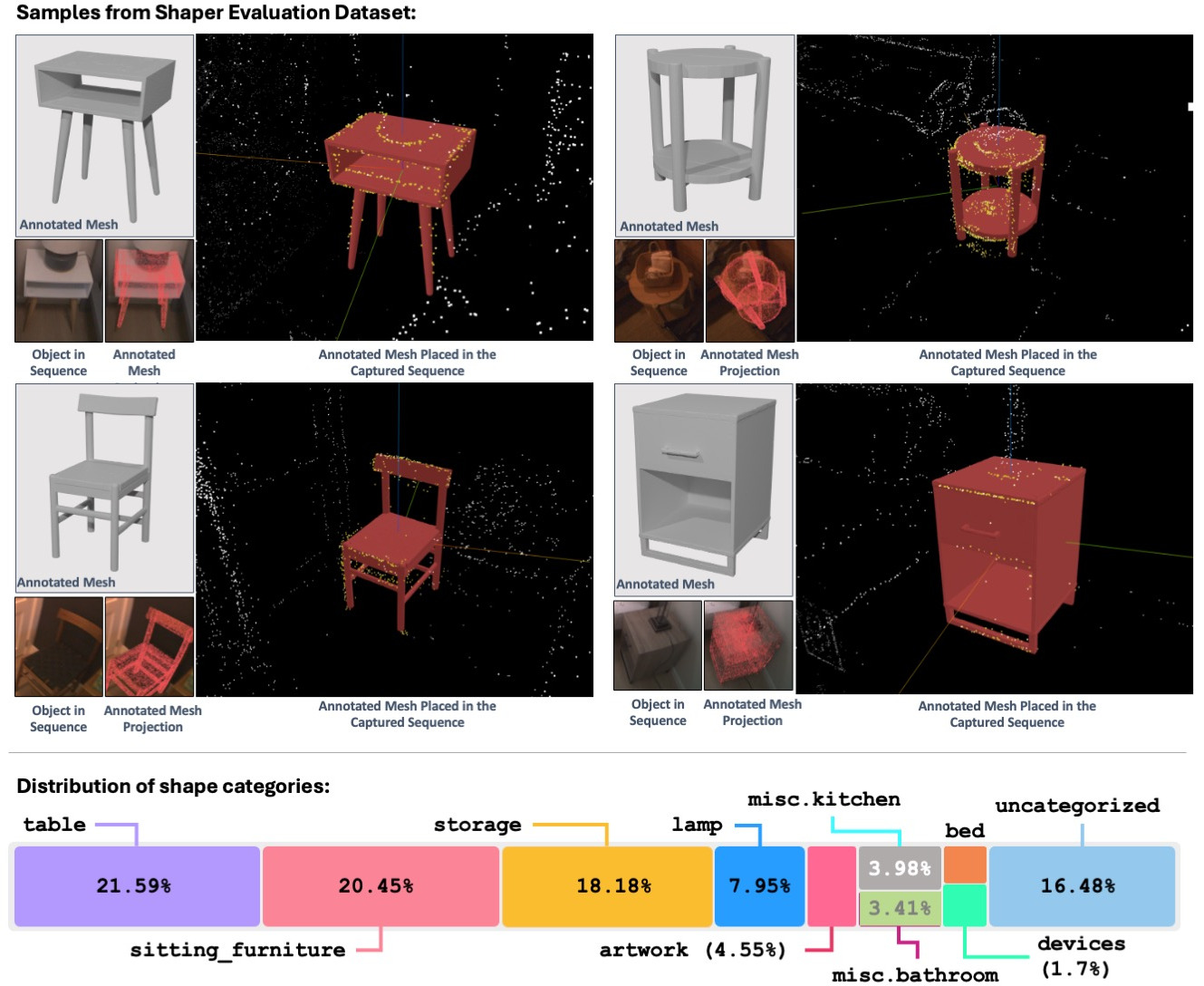

Abstract: Recent advances in 3D shape generation have achieved impressive results, but most existing methods rely on clean, unoccluded, and well-segmented inputs. Such conditions are rarely met in real-world scenarios. We present ShapeR, a novel approach for conditional 3D object shape generation from casually captured sequences. Given an image sequence, we leverage off-the-shelf visual-inertial SLAM, 3D detection algorithms, and vision-LLMs to extract, for each object, a set of sparse SLAM points, posed multi-view images, and machine-generated captions. A rectified flow transformer trained to effectively condition on these modalities then generates high-fidelity metric 3D shapes. To ensure robustness to the challenges of casually captured data, we employ a range of techniques including on-the-fly compositional augmentations, a curriculum training scheme spanning object- and scene-level datasets, and strategies to handle background clutter. Additionally, we introduce a new evaluation benchmark comprising 178 in-the-wild objects across 7 real-world scenes with geometry annotations. Experiments show that ShapeR significantly outperforms existing approaches in this challenging setting, achieving an improvement of 2.7x in Chamfer distance compared to state of the art.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces ShapeR, a computer system that can build accurate 3D models of everyday objects from short, casual phone videos. Unlike many previous methods that only work with clean, studio-like images or perfectly cut-out objects, ShapeR is designed for real-life, messy situations with clutter, occlusions, motion blur, and weird camera angles. It also keeps “metric” scale, meaning the size of the 3D model matches the real-world size.

Key Objectives

The paper sets out to answer simple but important questions:

- How can we turn a casual video of a scene (like a phone walk-around) into complete, true-to-scale 3D shapes of the individual objects in it?

- Can we make this work even when objects are partly hidden, the camera moves unpredictably, and the background is messy?

- Can we avoid requiring perfect object cut-outs in every image and still get great results?

How ShapeR Works (Methods)

Think of ShapeR as a smart tool that combines multiple clues to figure out an object’s 3D shape—like a detective using photos, dots, and labels to reconstruct a model.

The clues ShapeR uses

To make sense of a casual video, ShapeR gathers these inputs:

- Posed images: frames from the video where the system knows where the camera was for each shot.

- Sparse 3D points: a “connect-the-dots” set of points in space found by SLAM (software that tracks the camera and maps some 3D points from the video).

- Captions: short text descriptions of the object (like “a red toaster”) generated by a vision-LLM.

- Point projections: for the images it picks, it projects those 3D points onto the 2D pictures to roughly indicate where the object is in each view (no perfect cut-outs needed).

Together, these form a “multimodal” set of clues: images, 3D dots, and text.

The core idea, in everyday terms

- Shape code: ShapeR learns a compact “code” that describes a 3D shape (imagine a super-compressed blueprint).

- From noise to shape: It starts from random noise and learns how to “flow” that noise into the correct shape code by following small “arrows” that point in the right direction. This is called a rectified flow model. You can think of it as sculpting a statue from a messy clay blob using guidance from the images, dots, and caption.

- Decoding the shape: Once the code is ready, a decoder turns it into a full 3D mesh (the surface of the object). The mesh is then scaled back to match the object’s real size using the 3D points.

Training to handle messy videos

To make ShapeR tough and reliable, the authors train it in two stages and add lots of realistic “noise” during training:

- Stage 1: Pretraining on a huge variety of individual 3D objects. They deliberately mess up the inputs during training (add clutter, blur, low resolution, fake occlusions, point noise) so the model learns to be robust.

- Stage 2: Fine-tuning on more realistic synthetic scenes where multiple objects interact and occlude each other, better matching real-life videos.

This “curriculum” (easy first, then more realistic) helps ShapeR generalize to real-world captures.

A few helpful translations of terms

- SLAM: A method that figures out where the camera is and maps points in 3D, like leaving breadcrumb dots in space as you walk around.

- Sparse point cloud: Those breadcrumb dots—spread out, not dense, but still helpful.

- Metric: True-to-scale; a 1-meter table in real life is 1 meter in the 3D model.

- Mesh: The surface of the 3D object (like a net of tiny triangles).

- Flow model: A process that transforms noise into a meaningful shape code step-by-step, guided by the clues.

Main Findings

The authors built a new evaluation set with 178 objects across 7 real, cluttered scenes (images, camera poses, SLAM points, and high-quality shape references). On this tough benchmark:

- ShapeR significantly outperforms previous state-of-the-art methods in how close the reconstructed shape is to the ground truth, improving Chamfer distance by about 2.7× (lower is better; it measures how close two shapes’ surfaces are).

- It works even when:

- Objects are partly hidden or mixed in with other stuff,

- The views are poor,

- The image quality isn’t great, and

- No perfect object cut-outs are provided.

- It keeps real-world scale, so objects are the right size and fit together consistently in the scene.

- In user preferences against strong single-image 3D methods, people chose ShapeR’s results far more often, even though ShapeR runs automatically without manual help.

Why this matters: Many existing methods break down in real scenes because they depend on clean, segmented images or don’t preserve real scale. ShapeR solves both problems by using multiple clues and robust training.

Implications and Impact

- Practical 3D scanning: ShapeR brings us closer to simply walking around with a phone and getting reliable, to-scale 3D models of all objects in a room—no studio setup or manual tracing needed.

- Better AR/VR and robotics: Knowing accurate object shapes and sizes helps virtual experiences feel realistic and helps robots understand and navigate real spaces.

- Scene editing and asset creation: Designers and developers can extract high-quality, metrically accurate 3D assets from everyday videos.

- Research and benchmarking: The authors provide a new, realistic dataset and plan to release code and models, which can accelerate progress in object-centric 3D reconstruction.

In short, ShapeR is a big step toward automatic, reliable, and true-to-scale 3D object reconstruction from the kind of casual videos people actually capture in the real world.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following points identify what is missing, uncertain, or left unexplored in the paper, framed as concrete, actionable directions for future work:

- Quantitative metric grounding: validate “metric consistency” by reporting absolute scale and pose errors in physical units (e.g., mm/cm) rather than only shape metrics computed in normalized coordinates; add scene-level metrics (e.g., contact alignment, collision rate, scale drift).

- Scene composition evaluation: provide quantitative evaluation of assembled scenes (object-to-object and object-to-support relationships), including spatial consistency, collisions, and alignment with background surfaces.

- Modality contribution analysis: ablate text captions, pose encoding (Plücker rays), and image features (frozen DINOv2) to quantify each modality’s incremental benefit; test caption removal and random/incorrect captions to assess sensitivity.

- Dependence on 3D detection and SAM2 refinement: measure pipeline robustness to detection recall/precision errors and SAM2 failures; evaluate end-to-end variants that reduce or remove reliance on external instance detectors and mask-based point filtering.

- SLAM dependence and sensor diversity: test across different SLAM/SfM algorithms and sensors (e.g., smartphone monocular/RGB-only, stereo, different IMU qualities); quantify performance degradation under varying pose accuracy and point cloud sparsity.

- Sensitivity to capture conditions: systematically study the effect of number of views, view selection strategy, image resolution, motion blur, and persistent occlusions on reconstruction quality.

- Robustness to sparse or unreliable points: characterize performance as a function of SLAM point density, distribution, and noise; define minimum visibility/point thresholds for acceptable reconstructions.

- Dynamic and non-rigid objects: extend and evaluate on moving, articulated, and deformable objects to understand limitations of the current static, rigid assumption.

- Topology and thin-structure fidelity: measure watertightness, topological correctness, and recovery of thin parts (e.g., handles, cables); report SDF decoding resolution and its effect on topology.

- Uncertainty estimation: add shape uncertainty/confidence maps or probabilistic outputs to flag regions reconstructed mostly from priors versus observed evidence.

- Caption quality and semantics: evaluate the impact of caption accuracy, granularity, and noise; analyze failure modes when captions contradict visual/point signals or are generic.

- Generalization beyond Aria captures: benchmark on public, non-Aria datasets (smartphone casual videos, outdoor scenes, varied lighting) to test cross-domain robustness.

- Dataset scale and diversity: expand beyond 178 objects in 7 scenes to cover more categories (including reflective/translucent/textureless objects), environments (outdoors, industrial), and extreme occlusion/clutter cases.

- Ground-truth provenance and bias: quantify accuracy of “reference meshes” created with internal methods; report alignment and refinement procedures and their residual error to avoid benchmark bias.

- Fairness in baselines: compare against multi-view baselines under matched conditions (posed views, realistic segmentation/no segmentation) and report performance when GT-based cropping is not available.

- Runtime and scalability: report training and inference time/memory, throughput per scene, and scaling behavior with number of objects; characterize practicality for large scenes and on-device deployment.

- Latent length policy: study how variable VecSet length L affects quality, efficiency, and failure modes; develop criteria or predictors to select L per object.

- Failure mode analysis: provide systematic taxonomy and quantitative rates (e.g., adjacent-object confusion, over-completion, missing occluded regions), and correlate failures with input conditions.

- Augmentation efficacy breakdown: quantify the individual contribution of augmentation components (background compositing, occlusion overlays, SLAM point dropout/noise) with targeted ablations and controlled stress tests.

- Pose error robustness: inject controlled extrinsic/intrinsic noise during evaluation to measure tolerance and potential correction mechanisms (e.g., joint pose-shape refinement).

- Scene-level integration: investigate joint reconstruction across objects (shared context priors, global consistency constraints) versus purely per-object generation, and quantify benefits/costs.

- Materials and appearance: extend from geometry-only to materials/texture and evaluate how multimodal conditioning supports appearance reconstruction under casual capture.

- End-to-end learnability: explore training the detector/point-refinement modules jointly with the generative model to reduce brittleness and improve object localization under clutter.

- Ethical, privacy, and safety considerations: assess implications of reconstructing personal objects from casual captures and propose safeguards (e.g., on-device processing, anonymization).

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete use cases that can be deployed today, leveraging ShapeR’s ability to produce metrically accurate, complete object meshes from casually captured, posed multi-view sequences without explicit segmentation.

- E-commerce and Retail (software, logistics)

- Auto-generation of 3D product models for marketplace listings from short phone videos; includes real-world scale for AR try-on and accurate shipping dimension estimation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: requires posed multiview capture (ARKit/ARCore or SfM/SLAM), sufficient views with object visibility, GPU or cloud inference; current model outputs geometry (texture workflows may need an additional pipeline).

- Interior Design and Real Estate (AR/VR, construction)

- Room scans decomposed into per-object meshes (sofas, tables, appliances) with consistent metric scale for space planning, virtual staging, and fit checks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable 3D instance detection on cluttered scenes, minimal object motion during capture, integration with CAD/BIM tools for downstream layout.

- Robotics Perception Modules (robotics, software)

- Object-centric mapping for manipulation planning: robots build accurate meshes of target objects from egocentric video, improving grasp planning and collision avoidance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: egocentric SLAM availability (e.g., VIO), inference latency acceptable for offline/near-real-time use, scene dynamics limited during capture.

- Insurance and Claims (finance, risk)

- Rapid household or asset inventories with metrically accurate 3D meshes to document condition and dimensions; supports claim verification and fraud reduction.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consent and privacy controls for in-home capture, cloud processing governance, texture capture optional but helpful for damage documentation.

- Manufacturing and QA (industry, CAD)

- Quick geometry checks: reconstruct parts or assemblies from casual captures and compare meshes to CAD for dimensional deviations and fit assessments.

- Assumptions/dependencies: adequate view coverage, sufficient image resolution for small details, mesh-to-CAD alignment workflow; texture/material not required for geometry checks.

- Cultural Heritage and Museums (heritage, education)

- Digitization of stored collections in cluttered environments without controlled photogrammetry setups; object-centric meshes assembled into scene layouts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: multi-view access, stable lighting or robust augmentations, export formats compatible with archival pipelines.

- Warehouse and Field Asset Cataloging (logistics, energy)

- Object-level digital twins of tools, components, and panels from casual walkthroughs; supports inventory tracking, maintenance planning, and spatial audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: repeatable capture routes, object motion limited, integration with asset management systems for IDs/metadata.

- Game/Film Prop Acquisition (media, software)

- Rapid mesh acquisition of real props from cluttered sets; reduces manual segmentation and clean-scene requirements in content pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: pipeline-ready mesh export (OBJ/GLB), optional decimation/retopology steps, texture capture handled by existing tools.

- Education and STEM Labs (education)

- Classroom labs where students scan everyday objects to study geometry, scale, and spatial reasoning; supports project-based learning in 3D content creation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: mobile capture with ARKit/ARCore, institutional cloud/GPU access; minimal need for high-end textures.

- Research Benchmarking (academia)

- The ShapeR Evaluation Dataset enables systematic testing of object-centric reconstruction under occlusions and clutter; facilitates ablation studies and method comparisons.

- Assumptions/dependencies: dataset licensing and availability, code and weights release; alignment with common metrics (Chamfer, F-score, normals).

- Developer Tools and Workflows (software)

- “Video-to-Mesh” microservice API and Unity/Unreal plugins that take short multiview captures and return per-object meshes with real-world scale; optional scene composer for assembling objects.

- Assumptions/dependencies: SDK integration with SLAM/VIO, cloud inference endpoints, standard 3D formats, scene coordinate normalization and rescaling.

Long-Term Applications

These ideas require additional research, scaling, optimization, or productization (e.g., real-time performance, broader device support, texturing/materials, dynamic scenes), but are realistic extensions of ShapeR’s methods and findings.

- Real-Time On-Device Reconstruction (software, mobile, robotics)

- Interactive object capture on phones/headsets where meshes update live as users move, enabling immediate AR placement and measurement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: model distillation/quantization, hardware acceleration (Neural Engines/NPUs), efficient SLAM and detection on-device.

- Full Scene Understanding and Assembly (AR/VR, robotics, construction)

- End-to-end scene reconstruction that composes object meshes and layout with semantic labels, ready for digital twin creation and robot task planning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust scene graph inference, improved open-vocabulary detection, temporal consistency, layout optimization across objects.

- Textured, Material-Aware Assets (media, e-commerce)

- Coupling ShapeR’s geometry with PBR materials and textures for production-ready assets; supports lighting and relightable content.

- Assumptions/dependencies: integrated appearance modeling, consistent UVs/retopology, multi-view reflectance estimation.

- Dynamic Objects and 4D Reconstruction (robotics, media)

- Handling articulated and deformable objects over time (e.g., doors, tools, soft goods), enabling temporal meshes for manipulation and animation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: motion segmentation, temporal shape priors, robust tracking under occlusions.

- AR Occlusion and Physics-Ready World Models (AR/VR, robotics)

- Accurate object meshes with collision properties and physical parameters for realistic AR occlusion and robot simulation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: material inference for mass/rigidity, scene-scale calibration, physics engine integration.

- Construction/BIM Automation (construction, policy)

- Automatic as-built extraction of furniture, appliances, and fixtures from site walkthroughs; reconciles with BIM to track progress and compliance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: large-object capture at scale, alignment to building coordinates, change detection, BIM interoperability standards.

- Smart Home Inventory and Valuation (finance, consumer)

- Continuous in-home object catalogs with estimated replacement value and warranty linkage; assists insurance underwriting and claims.

- Assumptions/dependencies: privacy-preserving on-device processing, secure metadata standards, valuation models tied to geometry and brand recognition.

- City-Scale Object Indexing (geospatial, policy)

- Object-level maps (benches, signage, infrastructure components) from casual citizen captures; aids maintenance, accessibility audits, and urban planning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: crowd-sourced data governance, georeferencing, deduplication, municipal privacy and consent frameworks.

- Assistive Robotics for Elder Care and Accessibility (healthcare, robotics)

- Object-centric meshes for home assistance tasks (finding and retrieving everyday items) with robust occlusion handling in cluttered environments.

- Assumptions/dependencies: on-device perception, safety certifications, user consent and data protections, integration with manipulation controllers.

- Standardization and Policy (policy, cross-sector)

- Metadata standards for 3D object assets (units, provenance, capture method, confidence scores) and guidelines for privacy-preserving in-home scanning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: multi-stakeholder collaboration (industry, regulators, academia), audit trails for dataset/model usage, accessible consent UX.

- Marketplace of User-Generated 3D Assets (software, media)

- Platforms where users sell/licence accurate, metric 3D models of their objects; supports sustainable reuse and digital content creation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: content moderation, IP/rights management, quality validation pipelines, interoperability with major 3D tools.

- Cross-Modal Search and Retrieval (software)

- Search engines that index meshes generated from casual captures and allow retrieval via text, images, or spatial queries (e.g., “find all toasters with width < 30 cm”).

- Assumptions/dependencies: scalable mesh indexing, semantic captioning quality, unit-consistent metadata, privacy compliance.

- Safety-Critical Robotics Verification (policy, robotics)

- Certification pipelines that verify metric accuracy of reconstructed objects used by robots in safety-critical environments (hospitals, factories).

- Assumptions/dependencies: standardized accuracy benchmarks, reproducible capture protocols, third-party audits.

Notes across applications:

- ShapeR’s strength is robust, metric geometry under occlusion and clutter, using multimodal conditioning (posed images, sparse SLAM points, captions). It currently focuses on geometry (SDF-to-mesh), with textures/materials requiring complementary modules.

- Performance depends on: quality of SLAM/VIO and 3D instance detection, enough diverse viewpoints, limited motion blur, and compute availability. Extension to dynamic scenes, real-time operation, and appearance modeling are active development areas.

Glossary

- 2D Point Mask Prompting: Using 2D projections of 3D points as masks to indicate which pixels belong to an object, guiding image features during conditioning. "Effect of 2D Point Mask Prompting."

- 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS): A rendering technique that represents scenes with 3D Gaussian primitives for real-time view synthesis. "Recent approaches such as NeRF~\cite{mildenhall2021nerf}, 3DGS~\cite{kerbl20233d}, and their extensions~\cite{chen2022tensorf, muller2022instant, barron2021mip, barron2023zip, yu2024mip} achieve high-fidelity view synthesis but prioritize appearance over geometric accuracy."

- 3D instance detection: Detecting and localizing individual object instances in 3D space, often via bounding boxes. "Next, we apply 3D instance detection~\cite{straub2024efm3d} to extract object-centric crops from both images and point clouds"

- Amodal3R: A generative approach that reasons about occluded object parts to produce complete shapes beyond visible regions. "Amodal3R~\cite{wu2025amodal3r}, which extends TRELLIS~\cite{xiang2025structured}, improves robustness by reasoning about occluded regions and generating amodal completions."

- Aria Synthetic Environments: A synthetic dataset of realistic scenes used to simulate real-world occlusions, interactions, and noise patterns. "we then fine-tune on object-centric crops from Aria Synthetic Environment scenes, which feature realistic image occlusions, SLAM point cloud noise, and inter-object interactions."

- Chamfer distance: A geometry metric measuring the average closest-point distance between two shapes’ point sets. "Experiments show that ShapeR significantly outperforms existing approaches in this challenging setting, achieving an improvement of 2.7 in Chamfer distance compared to SoTA."

- CLIP: A multimodal model that embeds text and images into a joint space; used here for text conditioning. "Both dual and single stream blocks are modulated with timestep and CLIP~\cite{radford2021learning} text embeddings."

- Cross-attention: An attention mechanism that relates tokens from one modality/stream to another, used for conditioning and decoding. "The decoder predicts signed distance values for a grid of query points through cross-attention with the processed latent sequence."

- Curriculum learning: A training strategy that stages data complexity to improve generalization and robustness. "Training is conducted in a two stage curriculum learning setup"

- DINOv2: A pretrained vision transformer used as a frozen backbone to extract robust image tokens. "a frozen DINOv2~\cite{oquab2023dinov2} backbone extracts image tokens"

- Direct3DS2: A foundation image-to-3D model baseline used for comparison. "Direct3DS2~\cite{wu2025direct3d}"

- Dora (VecSets variant): A specific VecSets autoencoder variant for learning structured 3D latent representations. "We adopt the Dora~\cite{chen2025dora} variant of VecSets~\cite{zhang20233dshape2vecset} as our latent autoencoder."

- Dual-single-stream transformer: An architecture combining dual-stream cross-attention stages with single-stream self-attention for multimodal conditioning. "We employ a FLUX.1-like dual-single-stream transformer~\cite{batifol2025flux}"

- EFM3D: A benchmark and model reference for egocentric foundation models in 3D; used as a scene-centric baseline. "EFM3D~\cite{straub2024efm3d}"

- FLUX DiT architecture: A diffusion transformer architecture variant used as the backbone for the denoising model. "The ShapeR denoising transformer, built on the FLUX DiT architecture, denoises latent VecSets"

- Flow matching: A generative training paradigm learning velocity fields to transport noise to data distributions. "These multimodal cues condition a flow-matching~\cite{lipman2022flow} transformer"

- FoundationStereo: A large-scale stereo depth estimation model used to generate depths for TSDF fusion. "TSDF fusion with FoundationStereo depths~\cite{wen2025foundationstereo}"

- F-score (F1): A metric combining precision and recall for geometric accuracy at a distance threshold. "F-score (F1) at threshold."

- Hunyuan3D-2.0: A scaled diffusion-based model for textured 3D asset generation; used as a competitive baseline. "Hunyuan3D-2.0~\cite{zhao2025hunyuan3d}"

- MarchingCubes: An algorithm that extracts polygonal meshes from scalar fields like SDFs. ""

- MIDI3D: A scene-level generative model that predicts object geometry and layout from imagery. "We also compare against scene-level reconstruction methods, MIDI3D~\cite{huang2025midi}"

- NeRF: Neural Radiance Fields; a method representing scenes for high-quality view synthesis. "Recent approaches such as NeRF~\cite{mildenhall2021nerf}, 3DGS~\cite{kerbl20233d}, and their extensions"

- Normal Consistency (NC): A metric evaluating alignment of surface normals between reconstructed and reference shapes. "Chamfer Distance (CD), Normal Consistency (NC) and F-score (F1) at threshold."

- Normalized device coordinate (NDC) cube: The canonical coordinate range used for normalization in graphics, typically . "each objectâs point cloud is normalized to the normalized device coordinate cube ."

- Pl\"ucker encodings: A representation of rays (lines) in 3D used to encode camera poses and viewing geometry. "poses using Pl\"ucker encodings"

- Rectified flow: A variant of flow-based generative modeling that simplifies training by rectifying trajectories. "ShapeR formulates object-centric shape generation as a rectified flow process"

- ResNet (3D sparse-convolutional): A residual network adapted with sparse 3D convolutions for point cloud encoding. "a ResNet~\cite{he2016deep} style 3D sparse-convolutional encoder"

- SAM2: A segmentation model used to refine object point sets by removing spurious samples. "refined within its bounding box using SAM2~\cite{ravi2024sam} to remove spurious samples"

- SceneGen: A multi-view scene-level generative model producing object geometry and spatial layout. "SceneGen~\cite{meng2025scenegen}"

- SDF (Signed Distance Function): A scalar field giving the distance to a surface, with sign indicating inside/outside; used for implicit shape representation. "The denoised latent is decoded into a SDF, from which the final object shape is extracted using marching cubes."

- SfM (Structure from Motion): A method that reconstructs 3D structure and camera poses from images alone. "The point cloud is derived from images using SLAM or SfM;"

- SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping): A method estimating camera trajectory and building a map (e.g., sparse points) from sensor data. "off-the-shelf visual-inertial SLAM~\cite{engel2017direct}"

- Sparse-convolutional encoder (3D): A network using sparse 3D convolutions to efficiently process point clouds. "a ResNet style 3D sparse-convolutional encoder downscales the point features into a token stream."

- TSDF fusion: Integrating depth maps into a volumetric truncated signed distance field to reconstruct geometry. "TSDF fusion with FoundationStereo depths~\cite{wen2025foundationstereo}"

- Variational Autoencoder (VAE): A probabilistic autoencoder that learns latent distributions for generative modeling. "3D Variational Autoencoder."

- VecSets: A latent 3D shape representation as variable-length sequences of tokens encoding geometry. "VecSets~\cite{zhang20233dshape2vecset}"

- Vision-LLM (VLM): A model jointly processing images and text to produce captions or embeddings. "generate text captions using vision-LLMs~\cite{meta2025llama}"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.