Contrastive Geometric Learning Unlocks Unified Structure- and Ligand-Based Drug Design

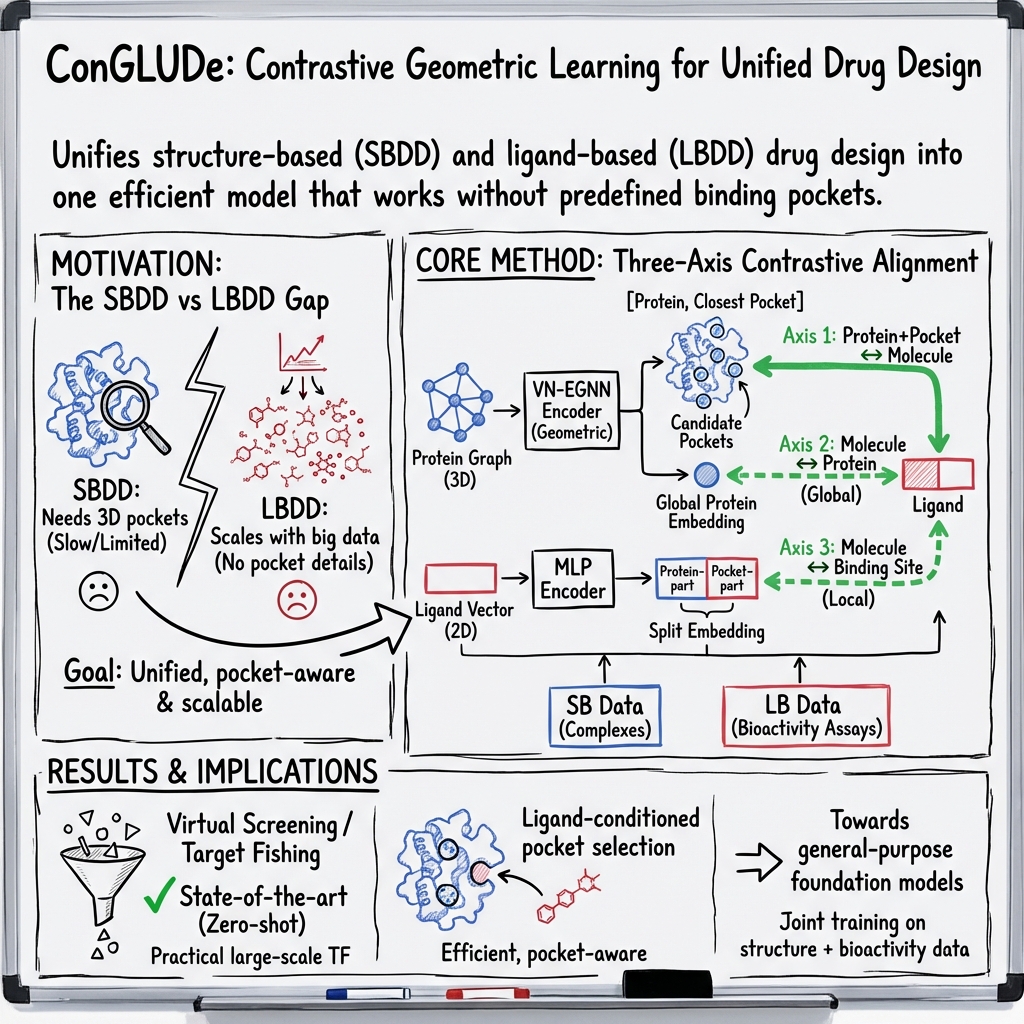

Abstract: Structure-based and ligand-based computational drug design have traditionally relied on disjoint data sources and modeling assumptions, limiting their joint use at scale. In this work, we introduce Contrastive Geometric Learning for Unified Computational Drug Design (ConGLUDe), a single contrastive geometric model that unifies structure- and ligand-based training. ConGLUDe couples a geometric protein encoder that produces whole-protein representations and implicit embeddings of predicted binding sites with a fast ligand encoder, removing the need for pre-defined pockets. By aligning ligands with both global protein representations and multiple candidate binding sites through contrastive learning, ConGLUDe supports ligand-conditioned pocket prediction in addition to virtual screening and target fishing, while being trained jointly on protein-ligand complexes and large-scale bioactivity data. Across diverse benchmarks, ConGLUDe achieves state-of-the-art zero-shot virtual screening performance in settings where no binding pocket information is provided as input, substantially outperforms existing methods on a challenging target fishing task, and demonstrates competitive ligand-conditioned pocket selection. These results highlight the advantages of unified structure-ligand training and position ConGLUDe as a step toward general-purpose foundation models for drug discovery.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces a new AI method called ConGLUDe that helps scientists discover new medicines. It does this by learning from two kinds of information about how small drug-like molecules (called ligands) interact with proteins in our bodies. ConGLUDe blends both “structure-based” and “ligand-based” data into one system so it can find likely binding spots on proteins, match them with the right molecules, and quickly screen huge compound libraries.

To make terms easy:

- Protein: a large biological molecule in your body that does important jobs.

- Ligand: a small molecule (often a drug) that can stick to a protein to change what it does.

- Binding pocket/site: the spot on a protein where a ligand can attach, like a keyhole.

- Virtual screening: testing many molecules on a computer to find which ones might stick to a protein.

- Target fishing: given a molecule, finding which proteins in the body it might bind to.

- Contrastive learning: a way for AI to learn by pulling matching pairs closer together and pushing non-matching pairs farther apart in its “memory space.”

Key Objectives

The researchers wanted to answer simple but important questions:

- Can one AI model learn both from 3D structures of protein–ligand pairs and from big activity datasets, instead of using two separate models?

- Can the model find binding pockets on a protein without being told where they are?

- Can it quickly match ligands to whole proteins and to the right binding pockets?

- Can it do fast, accurate virtual screening and target fishing even when pocket details are unknown?

How Did They Do It?

Think of the problem like matching keys to locks in a huge city:

- Proteins are buildings.

- Binding pockets are the keyholes on those buildings.

- Ligands are the keys.

- We want a smart guide that can find keyholes on buildings and match keys to the right keyholes and buildings—fast.

Here’s their approach:

- A protein “encoder” looks at the protein’s shape (its 3D structure) and spots where pockets might be. It also creates a summary of the whole protein. You can imagine this encoder like a drone scanning a building to mark possible doorways and making a building profile.

- A ligand “encoder” turns each molecule into a compact, easy-to-compare representation. Think of it as turning a key into a small digital card that captures its shape and features.

- Contrastive learning links these two: it trains the system so that the correct protein and ligand end up close together in memory space, and incorrect pairs end up far apart. It also aligns each ligand with both the whole protein and the most likely pockets on that protein.

Training with two types of data:

- Structure-based data: real 3D snapshots of proteins with ligands bound. This teaches the model to find and represent pockets, and to match ligands to those specific pockets.

- Ligand-based data: big collections of lab results showing which molecules are active against which proteins (but often without exact pocket positions). This teaches the model to match ligands to whole proteins even when pocket details aren’t known.

Because the model separates “making representations” from “comparing them,” screening becomes very fast: once everything is encoded, it just compares similarities—like checking which key card best matches which building’s profile and doorway profiles.

Main Findings

Across several tests, ConGLUDe showed strong, practical performance:

- Virtual screening without given pockets:

- On realistic benchmarks, ConGLUDe reached state-of-the-art or near state-of-the-art results even when pocket locations were not provided.

- It beat other “pocket-agnostic” models and remained competitive across different datasets, showing good generalization.

- Models that require known pockets can be very strong when that info exists, but in real life you often don’t have pocket details. ConGLUDe stays strong even then.

- Target fishing:

- Given a molecule and many proteins, ConGLUDe did the best job at finding the right targets in a challenging, out-of-domain test where pocket info was missing.

- It outperformed other methods, including more computationally heavy “docking” approaches, while being far faster.

- Binding pocket prediction:

- ConGLUDe kept the high accuracy of a strong pocket-prediction model it builds on, showing its pocket finder is robust.

- Ligand-conditioned pocket selection:

- When asked “which pocket on this protein is most likely to bind this particular ligand?”, ConGLUDe outperformed other baselines and did so much faster than docking methods.

Why this matters:

- It shows that training one unified model on both structure-based and ligand-based data improves versatility and performance.

- It enables fast screening and pocket-aware predictions without needing pre-defined pocket information.

Implications and Impact

In simple terms, ConGLUDe is a step toward an all-in-one AI helper for drug discovery:

- It can quickly scan proteins, find promising binding spots, and match them with the right molecules.

- It works even when detailed pocket info is missing, which is common in early research.

- It could help scientists reduce trial-and-error, save time, and focus experiments on the most promising candidates.

Limitations and next steps:

- It works best with good 3D protein structures; performance on uncertain or predicted structures may vary.

- It does not produce detailed “docked” poses of a ligand in a pocket; it focuses on scoring and selection. However, its pocket predictions can jump-start traditional docking workflows.

- Certain unusual pockets (like allosteric sites) remain more challenging, suggesting future improvements.

Overall, ConGLUDe pushes the field toward “foundation models” for drug discovery—general-purpose AI systems that learn from many kinds of data and support multiple tasks, making early-stage drug design faster and smarter.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, phrased concretely to guide follow-up research.

- Performance on predicted protein structures (e.g., AlphaFold) is unmeasured; quantify the accuracy drop versus PDB-resolved structures across diverse protein classes and folds.

- Generalization to proteins highly divergent from training templates (novel folds, membrane proteins, large complexes, disordered regions) is unknown; evaluate breadth across families (kinases, GPCRs, ion channels, nuclear receptors, enzymes).

- The model assumes assays with uniquely associated targets; extend to phenotypic or target-agnostic assays (cell-based screens) and develop methods to infer latent target–pocket associations from such data.

- Cosine similarity scores are not calibrated to binding probabilities or affinities; assess calibration (ECE, reliability diagrams) and correlations with continuous labels (Kd, IC50), and explore regression heads or calibrated contrastive scoring.

- ConGLUDe does not generate binding poses; investigate a fast pose module (e.g., conditional diffusion, retrieval-augmented docking) conditioned on predicted pockets and measure pose RMSD and docking success rates.

- Allosteric and cryptic pocket detection remains limited; curate allosteric training data, augment VN-EGNN for rare/cryptic sites, and quantify improvements on ASD and other allosteric benchmarks.

- Protein flexibility and induced fit are not modeled (static structures); evaluate multi-conformer/ensemble inputs, dynamic pocket representations, and assess gains on targets with conformational heterogeneity.

- Structural resolution is limited to Cα positions; test adding side-chain/atom-level coordinates, surface/mesh features, or learned 3D fields to improve pocket localization and ligand-conditioned scoring.

- Multi-chain and interface pockets (e.g., protein–protein interfaces) are not explicitly addressed; clarify handling of assemblies and evaluate binding site identification in hetero-oligomers.

- Ligand encoder uses 2D fingerprints/descriptors only; assess benefits and costs of 3D conformer-aware encoders (GNNs, equivariant models) and stereochemistry-sensitive features on pocket-conditioned tasks.

- Multi-site binding and ligand promiscuity (a ligand binding multiple pockets or targets) are not analyzed; measure the capacity to identify multiple plausible pockets per ligand and quantify trade-offs.

- Covalent binding (reactive warheads, residues) is unsupported; extend chemistry-aware features and tasks to covalent ligands and evaluate on covalent docking/affinity benchmarks.

- Cofactors, metals, and structured waters are not modeled; quantify their impact on pocket detection and ligand compatibility and test strategies to incorporate these features.

- Structure-based training labels treat all non-co-crystal pairs as negatives, introducing false-negative noise; quantify noise and test robust losses, semi-hard negative mining, and weak supervision to mitigate mislabeling.

- Contrastive temperature settings are fixed heuristics (1/√D, 1/√(2D)); perform sensitivity analysis, per-axis temperature learning, annealing schedules, and adaptive weighting across the three axes.

- VN-EGNN is frozen on ligand-based training; explore joint or alternating fine-tuning (e.g., pseudo-labels, consistency regularization, MIL) to let LB data refine pocket representations.

- Pocket clustering via DBSCAN lacks a stability analysis; study sensitivity to clustering hyperparameters, alternative clustering (mean-shift, OPTICS), and learned grouping to reduce pocket duplication or fragmentation.

- Score calibration for decision thresholds in screening (e.g., EF at fixed budget) is not addressed; derive calibrated thresholds or costs and assess deployable screening policies.

- Uncertainty estimates are absent; add ensembling, temperature scaling, or Bayesian heads to quantify uncertainty on pocket coordinates and interaction scores, and validate against OOD shifts.

- Throughput and resource profiling are not provided; benchmark inference/training runtimes, memory footprints, and scaling limits (proteome-wide × million-compound screens) versus docking and other CLIP-style models.

- Integration of known pocket inputs (when available) is not explored; enable a conditioned mode to incorporate supplied pocket structures and measure gains on DUD-E-like benchmarks.

- Bias and fairness across protein families and ligand chemotypes are unassessed; perform stratified analyses and debiasing (reweighting, domain adaptation) to mitigate dataset imbalance.

- Prospective validation (wet-lab) is missing; conduct blinded experimental screens or target fishing validations to quantify real-world hit rates and assay transferability.

- Target fishing evaluation is kinase-centric; test generalization to non-kinase proteomes and measure performance under broader domain shifts.

- Assay heterogeneity (concentration, readout types, batch effects) is not modeled; incorporate metadata-aware training or harmonization to improve robustness on LB datasets.

- ADMET and multi-objective optimization are stated as future directions but unimplemented; add multi-task heads and assess trade-offs between potency and ADMET endpoints.

- Variance across random seeds and training runs is only partially reported; expand stability analyses (more seeds, tasks), identify variance sources (data sampling, loss scales), and propose stabilization strategies.

- Interpretability at the residue level is limited; develop saliency/attribution over residues and pocket features to explain predictions and support hypothesis generation.

- CLOOB or other contrastive losses are suggested but not evaluated; compare loss formulations (CLOOB, InfoLOOB, supervised NCE variants) across tasks and domains.

- Pocket-level negatives in m2b are sampled within the same protein only; test cross-protein pocket negatives and hard-negative mining to sharpen pocket–ligand discrimination.

- Symmetry and redundant pockets (e.g., multiple equivalent sites) are not handled explicitly; design tie-breaking or symmetry-aware scoring and evaluate on symmetric oligomers.

- Data curation quality (PDB ligand/pose issues, misannotations) is not quantified; audit training labels (e.g., PDBBind ligand quality), filter/repair, and measure downstream impact.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The points below summarize practical, deployable uses of the paper’s method (ConGLUDe) across sectors, with suggested tools/workflows and key assumptions that affect feasibility.

- Healthcare/Pharma: Pocket-agnostic virtual screening at scale

- Use case: Triage large internal/vendor libraries against targets that lack known pockets; prioritize hits before docking or wet-lab assays.

- Workflow/tools: Encode proteins with ConGLUDe’s protein/pocket encoder; batch-score ligands via cosine similarity; funnel top-ranked pairs to docking (e.g., DiffDock, classical docking) and biochemical assays. Integrate into RDKit/KNIME/Nextflow pipelines and LIMS; deploy on cloud or on-prem HPC.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires 3D structures (PDB preferred; AlphaFold usage is promising but not fully characterized in this work). No binding poses are generated; downstream docking remains necessary for pose/structure-based decisions. Data curation and careful train–test separations are needed to avoid leakage.

- Healthcare/Pharma: Zero-shot target fishing and off-target profiling

- Use case: Identify likely protein targets and off-targets for leads and clinical candidates to inform selectivity, safety pharmacology, and repurposing.

- Workflow/tools: Score a ligand embedding against a proteome-scale set of protein embeddings; create ranked target lists; plan confirmatory biochemical/cellular assays and safety panels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Generalization to out-of-domain targets varies (shown strong on kinase proteomics data); thresholds need calibration; false positives/negatives must be risk-managed by orthogonal validation assays.

- Healthcare/Pharma & Structural Biology: Ligand-conditioned pocket selection

- Use case: Rapidly pick the most plausible binding site on a protein for a given ligand to guide docking, mutagenesis, and structural experiments (crystallography/cryo-EM).

- Workflow/tools: Predict pockets with VN-EGNN; rank pockets using ligand-conditioned similarity; dock only into top-ranked pockets; design mutations around predicted sites to validate binding.

- Assumptions/dependencies: VN-EGNN pocket detection governs recall; allosteric sites are harder to detect; accuracy depends on protein structure quality.

- Biotech/Software: Screening pipeline acceleration and compute cost reduction

- Use case: Replace or precede docking with efficient contrastive screening to cut GPU-days and turnaround time for library triage.

- Workflow/tools: ConGLUDe as a service/API in internal informatics; batch inference on CPU/GPU; dashboards for chemists to inspect ranked hits and pocket maps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Standardized molecular representations (SMILES/fingerprints) and protein structures required; secure handling of proprietary data; careful versioning to ensure reproducibility.

- Academia/Education: Teaching and benchmarking unified SB/LB modeling

- Use case: Courses and labs can adopt ConGLUDe (open-source) to demonstrate unified training across structure- and ligand-based data; replicate and extend benchmarks (DUD-E, LIT-PCBA, PDBbind).

- Workflow/tools: Use the GitHub repository; build assignments around pocket prediction, virtual screening, and target fishing; add ablation studies to teach model design and evaluation rigor.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to moderate compute (GPU optional for training; inference is light); adherence to data licensing for public datasets.

- Policy/Program Management: Resource prioritization and greener screening

- Use case: Institutional screening programs can use pocket-agnostic contrastive models to triage compounds before expensive assays or docking, saving cost and energy.

- Workflow/tools: Adopt tiered decision rules (contrastive screen → confirmatory docking → assay) and track energy/performance KPIs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Policy acceptance for AI triage; transparency/reproducibility standards; governance for model monitoring.

- Tools/products that can be stood up now

- SaaS/API for pocket prediction + screening; command-line tool for batch scoring; informatics dashboard showing pocket maps, ranked ligands, and target fishing results.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Compliance with IP/data privacy; CI/CD and model version control; monitoring drift when new proteins/assays are added.

Long-Term Applications

The points below outline opportunities that require further research, scaling, or development before broad deployment.

- Healthcare/Pharma: General-purpose foundation model for drug discovery

- Use case: A unified model trained across structural complexes and large-scale bioactivity to generalize zero-shot across targets, tasks (activity, affinity), and modalities.

- Potential products/workflows: Pretrained embeddings for whole proteomes; fine-tunable heads for affinity, selectivity, and ADMET; enterprise deployment in discovery suites.

- Assumptions/dependencies: FAIR, curated multi-source data; broader coverage of predicted structures; standardized assays and metadata; robust evaluation across families (GPCRs, ion channels, transporters).

- Pocket-conditioned generative design

- Use case: Generate novel ligands conditioned on pocket embeddings for fast de novo design and scaffold hopping with selectivity constraints.

- Potential products/workflows: ConGLUDe pocket embedding → generative model (e.g., graph or SMILES generator) → synthesis prioritization; closed-loop active learning with automated screening.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable pocket detection; generative model calibration; synthetic feasibility filters; multi-objective optimization; regulatory frameworks for AI-driven design.

- Phenotypic/target-agnostic assay integration

- Use case: Link ligand embeddings to phenotypes (cellular readouts, omics) and infer targets by contrastive triangulation; accelerate mechanism-of-action discovery.

- Potential products/workflows: Multimodal training with bioassays, transcriptomics/proteomics; causal inference pipelines; hypothesis generation tools for MoA.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality, aligned multimodal datasets; methods for confounding control; careful validation in wet-lab follow-up.

- Personalized/precision therapeutics

- Use case: Variant-aware screening—predict pocket changes and ligand binding in patient-specific protein variants to guide treatment selection or design.

- Potential products/workflows: Patient variant structure modeling → ConGLUDe pocket + ligand scoring → clinical decision support for rare mutations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate variant structures (AlphaFold/experimental); clinical-grade validation; regulatory approval and medical device compliance.

- Safety pharmacology and risk mitigation at scale

- Use case: Build comprehensive off-target risk maps by screening compounds across safety-relevant protein panels (e.g., hERG, CYPs, kinases) to reduce adverse events and animal use.

- Potential products/workflows: A safety portal integrating target fishing predictions with risk scoring and recommended follow-up assays.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Coverage of relevant protein families; calibrated risk thresholds; integration with post-marketing surveillance and pharmacovigilance data.

- Robotics/lab automation: Autonomous screening loops

- Use case: Integrate ConGLUDe with robotic platforms for iterative, data-driven compound selection, pocket validation, and assay scheduling.

- Potential products/workflows: Closed-loop orchestration (active learning) that feeds screening results back into model fine-tuning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Laboratory automation infrastructure; robust MLOps; real-time data pipelines.

- Structural biology experiment planning

- Use case: Use ligand-conditioned pocket predictions to design mutations, construct stabilizing variants, and plan cryo-EM/crystallography campaigns.

- Potential products/workflows: Pocket maps and mutational suggestions; integration with experimental design software.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Protein expressibility/stability; experimental throughput; model accuracy for non-canonical/allosteric sites.

- Public/consortial screening portals

- Use case: National or consortial platforms offering pocket-agnostic screening and target fishing capabilities to SMEs/academia for democratized discovery.

- Potential products/workflows: Cloud platforms with standardized data templates, audit trails, and governance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Funding, data-sharing agreements, IP governance, security and compliance.

- Finance/R&D portfolio analytics

- Use case: Portfolio-level prioritization using embeddings to assess repositioning, polypharmacology opportunities, and attrition risk.

- Potential products/workflows: Decision-support dashboards linking compound-target networks with program milestones and resource allocation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to high-quality internal data; organizational buy-in; integration with existing pipeline management tools.

Glossary

- ADMET: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity; pharmacokinetic and safety properties of drug candidates. "binding affinity or ADMET profiles."

- Allosteric: Referring to sites on a protein distinct from the orthosteric (active) site that modulate function when bound by a ligand. "due to allosteric pockets that are rarely seen during training"

- Allosteric Site Database (ASD): A curated database of experimentally validated allosteric binding sites. "the allosteric site database (ASD) \citep{liu2020unraveling}"

- AlphaFold: A deep learning system that predicts protein 3D structures from sequences. "With the advent of AlphaFold \citep{jumper_highly_2021}, structural encoding of target proteins without available PDB entries has also become possible"

- Ångström (Å): A unit of length commonly used in molecular structures (1 Å = 10-10 meters). "top-1 DCC success rate at a 4\AA\ threshold"

- AUPRC: Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve, a performance metric emphasizing positive class ranking. "AUPRC "

- AUROC: Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve, a classification performance metric. "measured by AUROC, BEDROC, and EF at 1\%."

- BEDROC: Boltzmann-Enhanced Discrimination of ROC, a metric emphasizing early retrieval in virtual screening. "measured by AUROC, BEDROC, and EF at 1\%."

- Binding affinity: The strength of interaction between a ligand and a protein target. "binding affinity or ADMET profiles."

- Binding pocket: A localized region on a protein where ligands bind. "settings where no binding pocket information is provided as input"

- Binding site: The specific location on a protein engaged by a ligand during binding. "binding site identification"

- Binding site prediction: Computational identification of likely ligand-binding regions on a protein. "we retain the performance of \ac{vnegnn} on binding site prediction"

- BindingDB: A public database of measured binding affinities between proteins and ligands. "BindingDB \citep{gilson2015bindingdb}"

- Bioactivity: Experimental measurement of a ligand’s effect on a biological target. "curated bioactivity data across thousands of targets"

- Blind docking: Docking performed without predefined knowledge of the binding pocket. "AI-based blind docking methods \citep{stark2022equibind,corso2023diffdock,pei2024fabindfastaccurateproteinligand}"

- Bootstrapping: A resampling technique used to estimate confidence intervals. "Values in parentheses indicate 95\% confidence intervals obtained by bootstrapping."

- Cα atom: The alpha carbon of an amino acid residue, used to represent residue positions in protein structures. "specifically, the position of the C atom"

- ChEMBL: A database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties and target annotations. "ChEMBL, which provides curated bioactivity data across thousands of targets"

- Chemical proteomics: Experimental techniques that profile ligand–protein interactions across proteomes. "Kinobeads chemical proteomics"

- Co-crystal structure: An experimentally resolved structure of a protein–ligand complex. "Proteinâligand pairs with observed co-crystal structures are labeled as positives ()"

- COACH420: A benchmark dataset for evaluating binding site prediction. "COACH420"

- CLOOB loss: A contrastive learning objective variant related to CLIP with orthogonality constraints. "Alternative contrastive formulations, such as the CLOOB loss \citep{furst2022cloob, sanchez2023}, could also be used."

- Contrastive learning: A representation learning approach that pulls semantically similar pairs together and pushes dissimilar ones apart. "contrastive learning has emerged as a powerful paradigm for modeling \acp{pli.}"

- DCC: Distance-based success criterion comparing predicted vs. true binding site centers at a threshold (e.g., 4 Å). "top-1 DCC success rate at a 4\AA\ threshold"

- DiffDock: A deep learning method for docking ligands into protein structures. "DiffDock \citep{corso2023diffdock}"

- DUD-E: Directory of Useful Decoys—Enhanced; a virtual screening benchmark dataset. "DUD-E \citep{mysinger_directory_2012}"

- Enrichment Factor (EF): A metric quantifying early enrichment of actives among top-ranked compounds. "EF at 1\%"

- ESM-2: A protein LLM used to generate residue feature embeddings from sequence. "extracted using ESM-2~\citep{lin2023evolutionary}"

- Free energy perturbation (FEP): Physics-based method estimating differences in binding free energies. "free energy perturbation \citep{beveridge1989free,cournia2021free}"

- HOLO4K: A large benchmark set of holo protein structures for pocket prediction evaluation. "HOLO4K"

- IC50: The concentration of a ligand that inhibits a biological process by 50%. "such as "

- InfoNCE: A contrastive loss function used to align positive pairs against negatives. "InfoNCE between a ligand and all pocket representations from the corresponding protein."

- Kinobeads: An affinity capture technology used in chemical proteomics to identify targets of kinase inhibitors. "Kinobeads chemical proteomics"

- Kd: The equilibrium dissociation constant, measuring binding affinity strength. "or continuous affinity values (), such as or $\text{K}_{\text{d}$."

- Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD): Designing drugs using ligand activity data without explicit structural binding geometries. "\Ac{lbdd} uses bioactivity data from large-scale biochemical assays."

- Ligand-conditioned pocket prediction: Ranking or selecting pockets based on the specific ligand to be bound. "ligand-conditioned pocket prediction"

- LigUnity: A contrastive learning method using hierarchical encoders for drug–target interaction. "LigUnity \citep{feng_hierarchical_2025}"

- LIT-PCBA: A virtual screening benchmark dataset focused on realistic assay outcomes. "LIT-PCBA \citep{TranNguyen2020LITPCBA}"

- MERGED dataset: A combined bioactivity dataset integrating PubChem, BindingDB, and ChEMBL. "we use the MERGED dataset curated by \citet{mcnutt2024sprint}"

- Molecular dynamics (MD): Simulation of time-dependent molecular motion to study interactions and stability. "molecular dynamics \citep{de2016role}"

- Morgan fingerprint: A circular topology-based molecular fingerprint used to encode ligand structure. "Morgan fingerprints~\citep{morgan1965generation}"

- Noise-Contrastive Estimation (NCE): A training principle framing probability estimation as a classification against noise samples. "The NCE loss between a protein and annotated ligand representations ($\mathcal L_{\mathrm{LB}$)"

- P2Rank: A machine learning–based protein pocket prediction tool. "either P2Rank \citep{krivak2018p2rank}"

- Protein Data Bank (PDB): The primary repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of biomolecules. "archived in the \ac{pdb} \citep{berman2000protein}"

- PDBbind: A dataset of protein–ligand complexes with binding data used for training and evaluation. "a subset of PDBBind \citep{wang2005pdbbind}"

- Pocket-agnostic method: A model that does not require predefined binding pocket information at inference. "pocket-agnostic methods do not assume prior pocket information"

- Proteochemometrics (PCM): Modeling approach that uses both protein and ligand descriptors to predict interactions. "proteochemometrics augments these models with protein representations"

- PubChem: A large public repository of chemical substances and bioactivity assays. "PubChem, which contains approximately 300M bioactivity measurements \citep{kin2025pubchem}"

- QSAR: Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship; modeling ligand activity from calculated molecular descriptors. "classical \ac{qsar} models"

- RDKit chemical descriptors: Computed molecular properties from the RDKit toolkit used as features for ligands. "RDKit chemical descriptors~\citep{rdkit}"

- Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD): Designing drugs using structural data (protein–ligand complexes, pockets). "\Ac{sbdd} relies on structural data describing the 3D conformations of ligands bound to protein binding sites."

- Sigmoid contrastive loss: A contrastive objective using a sigmoid over similarity scores for binary activity labels. "trained with a sigmoid contrastive loss \citep{gutmann2010noise,Seidl2023,zhai2023sigmoid}"

- SPRINT: A pocket-agnostic contrastive model encoding entire proteins for virtual screening. "SPRINT \citep{mcnutt2024sprint}"

- Target fishing: Identifying likely protein targets for a given small molecule. "Zero-Shot Target Fishing"

- Uni-Mol: A molecular representation framework used in several pocket-based contrastive baselines. "models with Uni-Mol-based encoders \citep{zhou2023unimol,gao2023drugclip,...}"

- VN-EGNN: Equivariant Graph Neural Network with virtual nodes for pocket prediction. "VN-EGNN employs a three-step heterogeneous message-passing scheme"

- Virtual screening (VS): Computationally ranking large libraries of compounds by predicted activity against targets. "virtual screening and target fishing"

- Wilcoxon test: A non-parametric statistical test for paired or matched samples. "(Wilcoxon test, )"

- Zero-shot learning: Making predictions for unseen tasks or targets without task-specific training examples. "Recent few-shot and zero-shot learning methods have extended activity prediction to scarce-data regimes"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.