Nested Learning: The Illusion of Deep Learning Architectures (2512.24695v1)

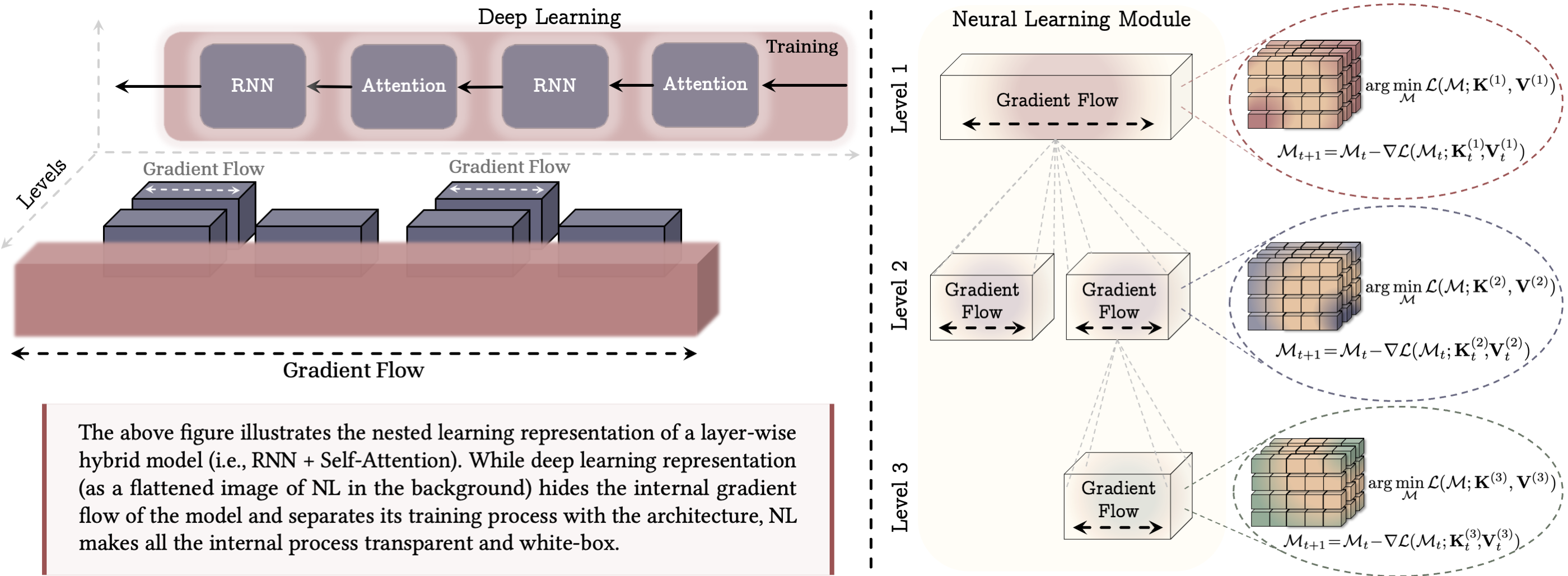

Abstract: Despite the recent progresses, particularly in developing LLMs, there are fundamental challenges and unanswered questions about how such models can continually learn/memorize, self-improve, and find effective solutions. In this paper, we present a new learning paradigm, called Nested Learning (NL), that coherently represents a machine learning model with a set of nested, multi-level, and/or parallel optimization problems, each of which with its own context flow. Through the lenses of NL, existing deep learning methods learns from data through compressing their own context flow, and in-context learning naturally emerges in large models. NL suggests a philosophy to design more expressive learning algorithms with more levels, resulting in higher-order in-context learning and potentially unlocking effective continual learning capabilities. We advocate for NL by presenting three core contributions: (1) Expressive Optimizers: We show that known gradient-based optimizers, such as Adam, SGD with Momentum, etc., are in fact associative memory modules that aim to compress the gradients' information (by gradient descent). Building on this insight, we present other more expressive optimizers with deep memory and/or more powerful learning rules; (2) Self-Modifying Learning Module: Taking advantage of NL's insights on learning algorithms, we present a sequence model that learns how to modify itself by learning its own update algorithm; and (3) Continuum Memory System: We present a new formulation for memory system that generalizes the traditional viewpoint of long/short-term memory. Combining our self-modifying sequence model with the continuum memory system, we present a continual learning module, called Hope, showing promising results in language modeling, knowledge incorporation, and few-shot generalization tasks, continual learning, and long-context reasoning tasks.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces a new way to think about how AI models learn, called Nested Learning (NL). Instead of seeing a model as just a stack of layers trained with one optimizer, NL treats the whole model and its training as a system of many smaller learning processes nested inside each other. Each part has its own “context” to learn from and its own speed of updating, a bit like different gears in a machine or different clocks in the brain. The goal is to build models that can keep learning over time (continual learning), adapt quickly to new tasks (in-context learning), and use memory more flexibly.

Key Questions the Paper Tries to Answer

- How can AI models learn continuously, not just during pre-training?

- Why do large models show “in-context learning,” and can we generalize this idea beyond Transformers?

- Are optimizers like SGD and Adam just tools, or are they themselves a kind of memory?

- Can we design models that modify their own learning rules as they run?

- Is there a better way to think about memory in AI than just “short-term” vs “long-term”?

How the Authors Approach the Problem

Big idea: “Nested Learning”

Imagine a school where each class has groups, each group has pairs, and each pair has a student with a notebook. Learning happens at all these levels, not just in the whole class at once. In NL, a model is like that: it has multiple “levels” of learning, each with:

- Its own context (what it’s trying to remember or compress),

- Its own update rule (how it changes),

- Its own speed (how fast it updates compared to others).

These levels can run in parallel or be stacked inside one another.

Associative memory (learning connections)

An associative memory links one thing to another—like remembering that “key” goes with “value.” The paper shows that many parts of AI systems are associative memories:

- Layers can learn to map inputs (keys) to useful outputs (values).

- Optimizers can learn to map gradients (signals of error) into better parameter updates.

This is similar to data compression: you squeeze the important information from the context into the model’s parameters.

Optimizers as memory

Optimizers like SGD, Momentum, AdaGrad, and Adam don’t just “move weights.” They store and compress information about gradients over time. In NL terms:

- They act like memory modules that learn from a stream of gradients.

- For example, Adam keeps track of average gradient size and direction; this is like a smart memory of “how the model has been wrong,” helping it fix mistakes more effectively.

The paper argues that, in theory, Adam is an optimal memory for certain kinds of “element-wise” learning tasks, when you measure error using a simple squared-distance goal.

Different speeds of learning (brain inspiration)

The brain uses different update speeds: fast waves for quick sensory processing, medium for focus, and slow for memory consolidation. The authors connect this to AI:

- Transformers behave like they have two extreme speeds: attention updates instantly using the context (like “infinite speed”), while MLP layers don’t change at test time (“zero speed”).

- NL suggests a spectrum of speeds so different parts can learn at different rates, helping with continual learning.

Self-modifying models and continuum memory

The paper proposes:

- A sequence model that can learn its own update rule—so it learns how to learn.

- A “Continuum Memory System (CMS)” that replaces the simple short-term/long-term story with many timescales. Fast parts adapt quickly but forget faster; slow parts change slowly but remember longer. Together, the system can partially recover forgotten knowledge and handle evolving tasks.

Simple examples and analogies

- Training a single layer: It can be seen as storing how “surprised” the model is by each input—like writing errors in a notebook so you don’t repeat them.

- Linear attention: Its fast memory matrix behaves like a key–value store that gets updated with each new input, while the projection layers are slower and trained by gradient descent. That’s already two nested learning levels.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

- Nested Learning gives a unified way to see models and optimizers as parts of one learning system. This helps explain why in-context learning appears and how to make it stronger.

- Popular optimizers (SGD with Momentum, Adam, AdaGrad) are shown to be associative memories that compress gradient information. This opens the door to designing “more expressive” optimizers for different contexts.

- The authors propose new ideas:

- Delta Gradient Descent (DGD): an update rule that depends not only on the new input but also on the current state of the weights—helpful when data points aren’t independent.

- Multi-scale Momentum Muon (M3): an optimizer with multiple momentum terms (multiple “memory speeds”) inspired by continuum memory.

- A self-modifying sequence model and a continuum memory system are combined into a module called “Hope.” The authors report promising results on:

- Language modeling and common-sense tasks,

- Few-shot generalization and in-context memorization,

- Continual learning (like adding new knowledge without forgetting old),

- Long-context reasoning (such as “needle-in-a-haystack” and BABILong benchmarks).

These results suggest models can become better at learning from ongoing experience, not just from huge pre-training batches.

Implications and Potential Impact

- Better continual learning: Models could keep learning after deployment, like students who keep studying over the school year, instead of freezing after one big exam.

- Stronger in-context learning: Seeing optimizers and layers as nested memories suggests new ways to boost how models use context on the fly.

- More unified, reusable architectures: Instead of mixing many unrelated blocks, NL points to a uniform design where everything is a learning module with its own speed—simpler and more brain-like.

- Smarter optimizers and memory systems: If optimizers are memory, we can tailor them to the task (gradients vs tokens) and build multi-speed memories that reduce forgetting.

- Practical improvements: The “Hope” module hints at real gains in long-context reasoning, adding new facts without wiping old ones, and handling new languages or categories with fewer examples.

In short, Nested Learning reframes modern AI as layered, self-updating memory systems. This view could help build models that learn continuously, adapt quickly, and remember more reliably—bringing AI closer to how human learning actually works.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved Gaps, Limitations, and Open Questions

The paper introduces the Nested Learning (NL) paradigm and related ideas (associative-memory view of optimizers, Continuum Memory Systems, self-modifying modules, DGD and M3 optimizers). Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored, to guide future research.

- Formalization of “nested, multi-level optimization”: The paper lacks a precise mathematical framework that specifies the levels, coupling terms, update rules, inter-level dependencies, and conditions for existence and stability of solutions in NL across nonconvex objectives.

- Convergence and stability guarantees: No theoretical analysis is provided for convergence, stability, and error propagation in multi-level NL systems (including bilevel/parallel components), especially under nonconvex losses, stochastic gradients, and streaming/non‑i.i.d. data.

- Learning or scheduling update frequencies: The choice of per-level update “frequencies” is not formalized; there are no algorithms to learn optimal time-scale separation, nor conditions under which learned schedules are stable and beneficial.

- Computational complexity and resource overhead: The compute, memory, and communication costs of multi-level nested optimizers and multi-frequency memory systems are not quantified; scalability to large models, long sequences, and distributed accelerators is unclear.

- Interference and credit assignment across levels: It remains unexplored how to prevent destructive interference between levels, perform credit assignment, and ensure consistent gradients/updates when levels write to shared parameters or memories.

- Empirical validation breadth and rigor: The claimed “promising results” lack detailed protocols, baselines, statistical significance, ablations, and reproducibility assets (code, seeds, checkpoints) across all tasks (language modeling, continual learning, long-context benchmarks).

- Comparative baselines to SOTA: Clear, competitive comparisons with state-of-the-art methods (Transformers, modern RNNs, hypernetworks, meta-learning methods, continual learning baselines like EWC, orthogonal gradients, replay) are missing.

- Measurement of “higher-order” in-context learning: The notion of higher-order ICL is not operationalized; there is no metric, diagnostic, or experimental protocol to quantify and validate the claimed higher-order capabilities.

- Associative memory interpretation of optimizers: The claim that SGD/momentum/Adam are associative memories that “compress gradients” lacks rigorous derivation of the underlying objective, approximation class, and generality beyond idealized settings; conditions under which Adam is “optimal” for element-wise L2 regression need formal proof and limits.

- Generality beyond gradient-based methods: NL’s unifying view is argued largely for gradient-based optimizers; how NL extends to second-order methods, proximal/variance-reduced methods, reinforcement learning, and non-differentiable objectives is unspecified.

- Delta Gradient Descent (DGD) algorithm details: DGD is introduced but not fully defined (update rule, hyperparameters, theoretical properties, convergence, noise sensitivity, stability on non‑i.i.d. streams), nor empirically compared across diverse tasks/datasets.

- Multi-scale Momentum Muon (M3) optimizer: M3’s formulation, parameterization (number of momenta, decay rates, coupling), convergence analysis, robustness to gradient noise, and empirical trade-offs against Adam/Adafactor/Shampoo are missing.

- Self-modifying sequence module: The architecture, learning objective, safety constraints, and training procedure for modules that learn their own update rules are not specified; guarantees against divergence, catastrophic interference, and misalignment are absent.

- Continuum Memory Systems (CMS) implementation: The CMS concept lacks a concrete algorithmic instantiation within standard architectures (e.g., Transformer MLPs), including how multi-frequency neurons are parameterized, updated, and integrated with attention/recurrence.

- Memory capacity and retention trade-offs: There is no analysis of CMS capacity, retention curves, stability-plasticity trade-offs, or quantitative comparisons with short/long-term memory baselines (e.g., replay buffers, key–value memories).

- Recovery of “forgotten” knowledge: The claim that CMS enables recovery after forgetting needs a formal mechanism, measurable protocol, and empirical evidence (e.g., controlled forgetting/restoration experiments).

- Bridging to neurophysiology: The mapping between brain oscillation bands and model update frequencies remains qualitative; controlled experiments demonstrating causality or performance benefits from specific frequency regimes are missing.

- Transformers as “extreme frequency” systems: The assertion that attention and MLPs correspond to ∞ and 0 update frequencies lacks a formal derivation or empirical validation; a rigorous mapping of transformer components to NL frequency semantics is needed.

- Knowledge transfer pathways between levels: The paper mentions level-to-level transfer but does not specify mechanisms (gating, adapters, distillation, parameter sharing) or how to avoid mode collapse/conflicts in transfer.

- Meta-learning unification: A formal equivalence or reduction showing how NL subsumes MAML/Reptile/learned optimizers (including sample efficiency and generalization bounds) is missing; benchmarks tying NL to known meta-learning tasks would help.

- Robustness and OOD generalization: It is unclear how NL/CMS/DGD/M3 affect robustness to distribution shift, adversarial inputs, and rare-event generalization across modalities (text, vision, multimodal).

- Safety, alignment, and auditability: Self-modifying continual learners raise risks (data poisoning, drift, misalignment); there are no proposed safety constraints, verification steps, audit trails, or rollback mechanisms.

- Practical training/inference pipelines: The suggestion to avoid rigid train/test phases lacks concrete deployment protocols (streaming data ingestion, checkpointing, evaluation windows, resource management) and guidance for real-world systems.

- Architecture–optimizer co-design: While advocating optimizer/architecture co-design, there is no framework or algorithm for deriving architecture-specific optimizers, nor criteria for when co-design materially improves performance.

- Relation to existing RNN/linear-attention FWPs: The novelty over established fast-weight programmers, linear attention, and modern RNNs (e.g., RWKV, Titans) is not sharply delineated; controlled comparisons to isolate what NL uniquely contributes are needed.

- Mathematical rigor and notation issues: Several equations/notations appear incomplete or contain typographical errors; a cleaned, fully specified formalism is needed to ensure reproducibility and unambiguous interpretation.

Glossary

- Adam: An adaptive gradient-based optimization algorithm that maintains running estimates of first and second moments of gradients to adjust learning rates per parameter. "We show that known gradient-based optimizers, such as Adam, SGD with Momentum, etc., are in fact associative memory modules that aim to compress the gradients' information (by gradient descent)."

- AdaGrad: An adaptive optimizer that scales learning rates inversely proportional to the square root of the sum of past squared gradients, benefiting sparse features. "gradient-based optimizers such as gradient descent with momentum, Adam~{kingma2014adam}, and AdaGrad~{duchi2011adaptive} can be decomposed into a two-level nested optimization problems"

- Anterograde amnesia: A neurological condition in which new long-term memories cannot be formed after onset, used here as an analogy for static models that cannot update long-term memory post-training. "anterograde amnesiaâa neurological condition where a person cannot form new long-term memories after the onset of the disorder"

- Associative memory: A system that learns mappings between keys and values, enabling retrieval of associated items; in this paper, many modules (optimizers, layers) are framed as associative memories. "Associative memoryâthe ability to form and retrieve connections between eventsâis a fundamental mental process"

- Backpropagation: The gradient-based procedure for computing parameter updates via chain rule, viewed here as compressing prediction errors into parameters. "we argue that training a deep neural network with backpropagation process and gradient descent is a compression and an optimization problem"

- Beta waves: Neural oscillations in the 13–30 Hz range associated with active thinking and intermediate timescales of processing. "Beta waves (frequency of $13$ - $30$ Hz)"

- Brain oscillations: Rhythmic fluctuations in neural activity that coordinate computation and learning across timescales. "Brain oscillations (also known as brainwaves)âa rhythmic fluctuations in brain activityâis not mere byproducts of brain function"

- Catastrophic forgetting: The abrupt loss of previously learned knowledge when a model is trained sequentially on new tasks. "might suffer from catastrophic forgetting~{eyuboglu2025cartridges, yu2025finemedlmo, akyureksurprising}"

- Continuum Memory System: A memory formulation with a spectrum of update frequencies, generalizing beyond a strict short/long-term dichotomy. "Continuum Memory System: We present a new formulation for memory system"

- Delta and Theta waves: Slow neural oscillations (0.5–8 Hz) implicated in memory consolidation and learning. "slow Delta and Theta waves (frequency of $0.5$ - $8$ Hz)"

- Delta Gradient Descent (DGD): A proposed optimizer whose updates depend on both current input and the state of the weights, capturing dependencies beyond i.i.d. assumptions. "a new variant of gradient descent, called Delta Gradient Descent (DGD)"

- Fast Weight Programmers (FWPs): Recurrent models with a matrix-valued fast-changing memory updated online by a separate “programmer” network. "Fast weight programmers (more recently refer to as linear Transformers)"

- Follow-the-regularized-leader (FTRL): An optimization scheme that selects parameters minimizing accumulated linearized losses plus a regularization term. "yields the followâtheâregularizedâleader (FTRL) form"

- Hebbian: Refers to learning rules that update connections based on co-activation (e.g., outer-product style); used here to describe a form of fast-weight update. "A basic (Hebbian/outerâproduct) FWPâoften called vanilla FWPâupdate its parameters with:"

- Hypernetworks: Networks that generate parameters for other networks, enabling dynamic and context-dependent weight generation. "hypernetworks,~etc."

- In-context learning: The ability of a model to adapt behavior to a given context (e.g., prompts, examples) without updating long-term parameters. "in-context learning naturally emerges in large models."

- Key–value memory: A structured memory storing pairs of keys and values to enable associative retrieval in sequence models. "providing a compact, learnable keyâvalue memory with constant state size across time."

- Linear attention: An attention mechanism with linear complexity achieved via kernel feature maps or fast-weight formulations. "we replace the MLP module in our previous example with a linear attention~{katharopoulos2020transformers}"

- Local Surprise Signal (LSS): The local error or mismatch signal at the output representation, used to quantify how surprising a prediction is. "mapping data samples to their Local Surprise Signal (LSS) in representation space"

- Long-term/short-term memory (LSM): The traditional dichotomy of memory systems, contrasted here with a continuum of update frequencies. "``long-term/short-term memory''"

- Meta learning: A two-level learning paradigm where an outer procedure learns to configure inner learning processes across tasks. "Meta learning paradigm (or learning to learn)"

- Momentum (SGD with Momentum): An optimization technique that accumulates a velocity vector to accelerate gradient descent and smooth updates. "Adam, SGD with Momentum, etc., are in fact associative memory modules"

- Multi-scale Momentum Muon (M3) optimizer: An optimizer with multiple momentum terms operating at different timescales, inspired by continuum memory design. "Multi-scale Momentum Muon (M3) optimizerâan optimization algorithm with multiple momentum terms"

- Neuroplasticity: The brain’s capacity to reorganize and adapt structurally and functionally in response to experience and learning. "neuroplasticityâthe brain's remarkable capacity to change itself"

- Non-parametric (solution): A method that adapts behavior based on data without relying solely on fixed learned parameters (e.g., attention over context). "being a non-parametric solution to a certain regression objective on tokens"

- Out-of-distribution data: Inputs drawn from a distribution different from the training data, challenging model generalization. "out-of-distribution data"

- Proximal update: An optimization step that minimizes a linearized loss plus a regularization term that keeps updates close to previous parameters. "precisely a proximal update on the linearization of "

- Rank-one update: A matrix update formed by an outer product of two vectors, common in fast-weight memory updates. "it is written by rankâone update and read by a matrixâvector multiplication"

- Recurrent neural networks (RNNs): Sequence models with cyclic connections and persistent state, including modern variants and fast-weight views. "modern recurrent neural networks~{katharopoulos2020transformers, schlag2021linear, peng2025rwkv7, behrouz2024titans}"

- Sharp-wave ripples (SWRs): High-frequency hippocampal oscillations implicated in memory replay and systems consolidation. "sharpâwave ripples (SWRs) in the hippocampus"

- Sleep spindles: Bursts of oscillatory brain activity during sleep involved in memory consolidation and communication across regions. "coordinated with cortical sleep spindles and slow oscillations"

- Steepest-descent: An interpretation of gradient descent as moving in the direction of maximal decrease under a given metric. "steepestâdescent in the Euclidean metric"

- Synaptic consolidation: A rapid, online stabilization process that transforms fragile new memories into more durable forms. "A rapid ``online'' consolidation (also known as synaptic consolidation) phase"

- Systems consolidation: A slower, offline process of memory reorganization and transfer across brain regions, often during sleep. "An ``offline'' consolidation (also known as systems consolidation) process"

- Unnormalized linear attention: A linear-attention variant without explicit normalization of attention weights, derivable from gradient updates to memory. "equivalent to the update rule of an unnormalized linear attention"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following are deployable now or with minimal engineering effort, leveraging the paper’s methods (e.g., CMS, Hope, M3, DGD) and the NL design lens to improve existing systems and workflows.

- Industry: training efficiency and stability via optimizer improvements

- Use case: Swap-in M3 (Multi-scale Momentum Muon) for large-model training and fine-tuning to improve stability and gradient “memory” on noisy, non-iid workloads (e.g., instruction tuning, streaming updates).

- Sectors: software/ML platforms, cloud providers, foundation model labs.

- Tools/products/workflows: optimizer plugin in PyTorch/JAX/TF; “multi-momentum bands” hyperparameter presets; AutoML optimizer selection that conditions on model block type (attention vs MLP).

- Assumptions/dependencies: need well-tested implementations; hyperparameter search; compatibility with mixed precision and distributed training.

- Industry: streaming and non-iid learning with DGD (Delta Gradient Descent)

- Use case: Online adaptation under covariate shift where sample dependence matters (e.g., recommender systems, ads ranking, real-time personalization, RL training loops).

- Sectors: ads/recsys, e-commerce, gaming, RLops.

- Tools/products/workflows: incremental training daemon that applies DGD updates on micro-batches; drift monitors that modulate delta sensitivity; replay buffers integrated with multi-timescale updates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: careful stability controls to prevent drift; audit logs for online updates; legal/privacy guardrails for continuous learning.

- Industry: continual learning in deployed assistants using Continuum Memory System (CMS)

- Use case: Enterprise assistants that absorb new knowledge without full retraining (e.g., support bot that learns company-specific updates), with fast “high-frequency” slots for immediate adaptation and slow slots for consolidation.

- Sectors: enterprise SaaS, customer support, productivity tools.

- Tools/products/workflows: CMS MLP replacement blocks in Transformers; “memory policy manager” that schedules consolidation and decay; per-tenant memory isolation; rollback/versioning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: safety filters; memory transparency UX; compute budget for periodic consolidation; validation suites to detect catastrophic drift.

- Academia: a unifying experimental lens for model design and analysis (Nested Learning)

- Use case: Compare architectures as associative memories; design architecture-specific optimizers; diagnose forgetting by visualizing nested gradient flows and “frequency bands.”

- Sectors: ML research, education.

- Tools/products/workflows: NL notebooks; “gradient-memory dashboards” that attribute error signals to levels; benchmarks that vary timescale structure (long-context, continual tasks).

- Assumptions/dependencies: requires instrumentation in training loops; standardized logging formats.

- Software engineering: faster domain adaptation and code-aware assistants

- Use case: Fine-tune code LMs with M3 and CMS blocks to rapidly internalize team patterns without overwriting global competencies; recover “forgotten” patterns via multi-frequency memory.

- Sectors: developer tools, IDEs.

- Tools/products/workflows: on-repo continual fine-tuner with consolidation windows (e.g., nightly); change-impact aware updates (delta-based).

- Assumptions/dependencies: repository privacy; rollback on regressions; evaluation on internal style/lint/unit tests.

- Finance and time-series: robust streaming models

- Use case: Apply DGD and M3 for non-iid, regime-shifting markets; multi-timescale modeling to blend fast reactions with slow consolidation.

- Sectors: finance, forecasting.

- Tools/products/workflows: multi-frequency update schedule tied to volatility; constrained self-updates during market stress; backtesting with level-specific ablations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: strict risk controls; regulatory model-change documentation; computational latency budgets.

- Healthcare and life sciences: incremental model updates under governance

- Use case: CMS-based adaptation to evolving clinical guidelines or local data without full retraining; minimize catastrophic forgetting.

- Sectors: healthcare, bioinformatics.

- Tools/products/workflows: “frozen slow layers + fast adapters” with periodic review; shadow deployments comparing levels; audit trails at each level.

- Assumptions/dependencies: regulatory approval; rigorous validation; privacy-preserving training.

- Robotics and control: multi-timescale policy updates

- Use case: Fast adaptation to environment perturbations with high-frequency memory; slow consolidation to preserve core skills.

- Sectors: robotics, autonomous systems.

- Tools/products/workflows: layered policy training (fast adapters + slow base); sim-to-real pipelines that control consolidation cadence; safety constraints on self-updates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: real-time compute; robust reset/recovery; safety certification.

- Daily life: personalized on-device assistants

- Use case: Keyboard, email, or note-taking assistants that learn user preferences over sessions (fast slots) and gradually consolidate stable habits (slow slots).

- Sectors: consumer apps, mobile.

- Tools/products/workflows: on-device CMS micro-adapters; “memory transparency” settings to view/edit retained knowledge; periodic consolidation during idle.

- Assumptions/dependencies: on-device efficiency; privacy-by-design; user control over memory lifespan.

- Policy and governance: auditability for dynamic models

- Use case: Document “levels” of memory and update frequency in model cards; log and approve changes by level; set retention/erasure policies that map to frequency bands.

- Sectors: model governance, compliance.

- Tools/products/workflows: level-aware model cards; change-management workflows that require sign-off for slow-level changes; differential retention policies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: organizational buy-in; alignment with regulatory frameworks (e.g., AI Act, HIPAA, SEC guidance).

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling, safety proofs, or standardization to reach production readiness.

- Self-improving, lifelong LMs with online consolidation

- Description: Eliminate the “static after deployment” phase by enabling models to continuously learn across nested levels, with principled consolidation and safe forgetting.

- Sectors: foundation models, consumer assistants, enterprise AI.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Memory OS” for LMs that schedules replay, decay, and consolidation; self-update governance and verification layers; memory-aware evaluation suites spanning months.

- Assumptions/dependencies: formal stability and safety guarantees; robust drift detection; privacy-preserving replay; new benchmarks and standards.

- Higher-order in-context learning and self-referential update learning

- Description: Models that not only learn tasks in context, but also learn how to change their own learning rules (self-modifying sequence models) to accelerate adaptation across domains.

- Sectors: AutoML, research tooling, edge AI.

- Tools/products/workflows: meta-optimizers embedded in the model; guardrails for update rule introspection; “safe sandboxing” for experimenting with learned updates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: strong safety constraints to avoid pathological updates; interpretability of learned rules; reproducibility across seeds and datasets.

- Uniform, reusable, multi-timescale architectures across modalities

- Description: Brain-inspired, frequency-banded architectures that unify text, vision, audio, and action with the same reusable blocks and multi-frequency update policies.

- Sectors: multimodal AI, robotics, AR/VR.

- Tools/products/workflows: common CMS blocks for all modalities; cross-modal consolidation schedules; hardware co-design for frequency-aware compute.

- Assumptions/dependencies: standardized interfaces; training curricula that exploit timescales; efficient cross-modal memory routing.

- Privacy-first continual learning at scale

- Description: Systems that maintain rich multi-level memories while guaranteeing privacy (e.g., per-level DP, tenant isolation, on-device consolidation with encrypted checkpoints).

- Sectors: enterprise, healthcare, finance, consumer.

- Tools/products/workflows: level-specific DP budgets; consent-aware memory layers; privacy audits tied to memory retention policies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: advances in efficient DP for online learning; legal frameworks for continual consent and data deletion; secure hardware support.

- Safety, evaluation, and regulation for self-modifying systems

- Description: Standards and tooling for validating, certifying, and monitoring models that change their internal update rules and long-term memory.

- Sectors: policy/regulation, certification bodies.

- Tools/products/workflows: “level-by-level” test batteries; red-teaming of consolidation logic; incident response playbooks for memory corruption or unsafe updates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consensus on metrics (e.g., safe retention/forgetting scores); third-party audit ecosystems.

- Neuromorphic and hardware acceleration for multi-frequency learning

- Description: Chips optimized for CMS-style updates (fast/slow bands), enabling energy-efficient lifelong learning at the edge.

- Sectors: semiconductors, mobile/edge devices, robotics.

- Tools/products/workflows: memory-tiered accelerators; schedulers that map levels to on-chip SRAM/DRAM/NVM; event-driven update units for high-frequency paths.

- Assumptions/dependencies: hardware–software co-design; compiler support for level scheduling; cost-effective fabrication.

- Autonomous financial and industrial agents

- Description: Agents that adapt online to regimes and equipment wear using multi-timescale memory, balancing short-term responsiveness with long-term safety.

- Sectors: finance, energy, manufacturing.

- Tools/products/workflows: risk-gated consolidation; simulation-to-field transfer curricula; audit logs for regulator review of level-wise updates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: stringent risk controls; regulator-approved change management; robust sim2real validation.

- Education: long-horizon personalized tutors

- Description: Tutors that retain student-specific knowledge across semesters (slow levels) while adapting to daily performance (fast levels), supporting few-shot generalization to new topics.

- Sectors: edtech.

- Tools/products/workflows: per-student memory partitions; teacher dashboards showing memory state by level; curriculum aligned with consolidation cycles.

- Assumptions/dependencies: privacy and parental consent; bias/robustness validation; scalable content alignment with memory policies.

- Knowledge management beyond RAG

- Description: Internal knowledge bases that are not just indexed externally, but consolidated inside the model’s multi-level memory to enable higher-order ICL and reasoning without heavy retrieval.

- Sectors: enterprise productivity, legal, research.

- Tools/products/workflows: hybrid pipelines that blend RAG with internal consolidation; “memory carpentry” to sculpt which concepts live at which levels; periodic decontamination passes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: scalable tooling for safe consolidation; provenance tracking; ability to reverse or compartmentalize memory.

- Scientific discovery tools

- Description: Models that can rapidly internalize new literature (fast) and synthesize durable insights (slow), improving hypothesis generation and long-context reasoning across evolving corpora.

- Sectors: pharma, materials, climate.

- Tools/products/workflows: ingestion pipelines tied to journal updates; cross-domain consolidation heuristics; scientist-in-the-loop gating for slow-level changes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: careful curation to avoid compounding errors; evaluation on longitudinal benchmarks; IP/licensing constraints for training data.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.