Pruning as a Game: Equilibrium-Driven Sparsification of Neural Networks (2512.22106v1)

Abstract: Neural network pruning is widely used to reduce model size and computational cost. Yet, most existing methods treat sparsity as an externally imposed constraint, enforced through heuristic importance scores or training-time regularization. In this work, we propose a fundamentally different perspective: pruning as an equilibrium outcome of strategic interaction among model components. We model parameter groups such as weights, neurons, or filters as players in a continuous non-cooperative game, where each player selects its level of participation in the network to balance contribution against redundancy and competition. Within this formulation, sparsity emerges naturally when continued participation becomes a dominated strategy at equilibrium. We analyze the resulting game and show that dominated players collapse to zero participation under mild conditions, providing a principled explanation for pruning behavior. Building on this insight, we derive a simple equilibrium-driven pruning algorithm that jointly updates network parameters and participation variables without relying on explicit importance scores. This work focuses on establishing a principled formulation and empirical validation of pruning as an equilibrium phenomenon, rather than exhaustive architectural or large-scale benchmarking. Experiments on standard benchmarks demonstrate that the proposed approach achieves competitive sparsity-accuracy trade-offs while offering an interpretable, theory-grounded alternative to existing pruning methods.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper looks at a new way to shrink (prune) neural networks so they run faster and use less memory. Instead of cutting parts based on simple rules after training (like “small weights get removed”), the authors treat the network like a group project: each part (a weight group, neuron, or filter) decides how much to “participate.” If a part isn’t helping enough or overlaps too much with others, it naturally chooses to back off to zero participation—meaning it effectively removes itself. The big idea is that sparsity (many zeros) should emerge on its own as a fair, stable outcome of the parts interacting, not as something we force afterward.

What questions does the paper ask?

The paper centers on three easy-to-understand questions:

- Can we think of pruning as a “game” where each network part chooses how much to help?

- If we do that, will some parts naturally choose to “sit out,” creating a sparse (smaller) network?

- Can this idea lead to a simple, practical pruning method that keeps accuracy while removing lots of unnecessary parts?

How does the method work?

Think of a neural network as a team working on a group assignment:

- Each teammate (a neuron or filter) has a slider from 0 to 1 that sets how much they participate. 1 means “fully in,” 0 means “not participating.”

- Every teammate gets a “score” (utility) that balances helping the team (reducing mistakes) against costs:

- Cost for being big or complicated (like taking too much space/energy).

- Cost for doing the same job as someone else (redundancy/overlap).

Key ideas explained simply:

- Participation sliders: Each neuron has a participation level, like a volume knob. Turn it down if you’re not adding unique value; turn it up if you help reduce errors.

- Benefit: How much a neuron helps reduce the network’s mistakes. If changing that neuron makes the model better, its benefit is high.

- Costs:

- “L2” cost: penalizes being large; it pushes participation toward smaller values when you’re not useful.

- “L1” cost: encourages exact zeros; it makes it easier to fully turn a neuron off.

- “Competition/overlap” cost: if two neurons do almost the same thing, one should step back to avoid duplication.

- Nash equilibrium (simple version): a stable situation where no single neuron can improve its own score by changing its participation. At this point, some neurons naturally end up at zero (pruned), and the rest stay active.

Training procedure in plain terms:

- Train the normal weights as usual.

- At the same time, adjust the participation sliders up or down based on whether each neuron is helping more than it costs.

- If a slider sinks near zero and stays there, that neuron is effectively removed.

What did they test and what did they find?

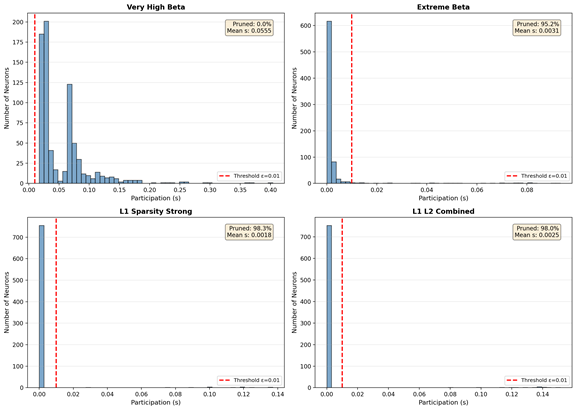

They tested their method on MNIST (handwritten digits 0–9) using a simple two-hidden-layer network. They tried different settings for the costs to see how easily neurons would turn themselves off.

Main findings:

- With stronger cost settings, many neurons smoothly “decide” to stop participating during training—no hard, after-the-fact cuts needed.

- The final participation levels tend to split into two groups: near 0 (off) or near 1 (on). Very few sit in the middle. This is a sign of a stable equilibrium where neurons make clear “in or out” choices.

- They achieved extreme sparsity while keeping decent accuracy. For example, in one setup they kept under 2% of neurons and still got over 91% test accuracy on MNIST. This shows the original network had a lot of redundancy.

Why this matters:

- It explains pruning behavior in a principled way. Instead of guessing which parts to cut, the network’s own dynamics decide.

- It connects and “explains” popular pruning tricks: magnitude-based pruning, gradient-based pruning, and redundancy-aware pruning all appear as special cases of this game-like setup.

What’s the bigger picture?

Implications and potential impact:

- Smarter, smaller models: This approach can produce compact networks without multi-step “train → prune → fine-tune” pipelines, saving time and energy.

- More interpretable pruning: We can say “this neuron turned itself off because it wasn’t helping enough and overlapped with others,” which is easier to understand and justify.

- A foundation for future methods: The game viewpoint could guide better pruning for different parts of networks (like channels or filters) and might help with bigger models, too.

Limitations and next steps:

- The experiments are on a simple dataset (MNIST) and a small network. Scaling to deeper models and huge datasets (like LLMs) may require extra care, better tuning, and attention to numerical stability.

- Still, the idea provides a clear, theory-based path to new pruning algorithms that could be both effective and easier to explain.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concise list of what the paper leaves unresolved, focusing on missing theory, algorithmic details, empirical validation, and practical considerations that future work could address.

- [Theory] No formal proof of existence/uniqueness of Nash equilibria under the proposed utilities; specify conditions on α, β, γ, η and properties of the loss (e.g., smoothness, Lipschitz constants) that guarantee equilibrium existence and convergence of the alternating updates.

- [Theory] The claim that “dominated strategies collapse to zero under mild conditions” lacks a rigorous theorem and proof; delineate precise assumptions and provide formal convergence guarantees (including treatment at the non-differentiable point s_i=0).

- [Theory] Stability analysis is only sketched (“contraction when η is not too large”); derive explicit Jacobian/Lipschitz bounds and parameter ranges ensuring stability and convergence (or characterize cases with cycles/multiple equilibria).

- [Theory] The game’s relationship to potential games is unclear; determine whether a potential function exists and, if so, design provably convergent optimization dynamics; if not, analyze possible non-convergent behaviors.

- [Modeling] The benefit term B_i=α s_i ⟨∇_{θ_i} L, θ_i⟩ is a crude linearization; evaluate whether it faithfully measures marginal contribution, and compare against alternatives (e.g., loss change upon ablation, Fisher information, Shapley values, activation gradients).

- [Modeling] The competition cost uses weight inner products ⟨θ_i, θ_j⟩, which may not reflect representational redundancy; assess activation-based redundancy (e.g., representational similarity, mutual information) and its impact on equilibria.

- [Modeling] η (competition) is set to zero in practice, undermining the central claim of “strategic interaction”; perform experiments with nonzero η, define robust similarity measures across parameter groups, and quantify its effect on pruning and accuracy.

- [Modeling] Scale invariance/degenerecy: because f depends on s_i θ_i, re-scaling θ_i→c θ_i and s_i→s_i/c can reduce the L1 term without changing the function; formally analyze this invariance and introduce safeguards (e.g., explicit weight decay on θ, normalization constraints, proximal updates) to prevent pathological solutions (e.g., exploding θ with vanishing s).

- [Optimization] Handling of the L1 non-differentiability at s_i=0 is ad hoc via sign(s_i); replace with principled subgradient/proximal operators and provide convergence analysis under stochastic updates.

- [Optimization] The utility uses stochastic mini-batch gradients; study robustness to noise, oscillations near the pruning threshold, and whether averaging/momentum/annealing schedules for η_s improve stability and selection consistency.

- [Hyperparameters] No principled method to set α, β, γ, η, or learning rates; develop sensitivity analyses, automated tuning (e.g., bilevel optimization), or continuation schedules to target desired sparsity while maintaining accuracy.

- [Control] Lack of explicit mechanism to hit a target sparsity level; introduce constraints or dual variables (e.g., Lagrangian formulations) that enforce a sparsity budget at equilibrium.

- [Granularity] Only neuron-level gating in an MLP is explored; extend and validate for filters/channels in CNNs, attention heads/MLP blocks in Transformers, and structured groups (blocks, layers), including how to define θ_i and competition for heterogeneous shapes.

- [Implementation] For neurons, the exact application of s_i to incoming vs outgoing weights/activations is under-specified; clarify gating semantics to avoid unintended scaling interactions (especially in architectures with residual connections or normalization layers).

- [Numerics] The paper notes potential ill-conditioning but offers no diagnostics or remedies; systematically monitor condition numbers and propose stabilization (normalization, gradient clipping, adaptive penalties) for deeper/wider networks.

- [Empirical] Evaluation is restricted to MNIST with a small MLP; test scalability on CIFAR-10/100, ImageNet, ResNets, ViTs/Transformers, and LLMs to assess generality and performance in realistic settings.

- [Empirical] No controlled comparison against standard pruning baselines (magnitude, OBD/OBS, lottery ticket, dynamic sparse training) on the same tasks; provide matched benchmarks and ablations to substantiate “competitive trade-offs.”

- [Empirical] The reported MNIST accuracy (~91–96%) is substantially below typical dense baselines (~98%+); quantify accuracy–sparsity Pareto curves, include post-pruning fine-tuning, and analyze regime where equilibrium pruning remains competitive.

- [Empirical] No analysis of per-layer pruning distribution and its effect on performance; investigate whether certain layers are disproportionately pruned and whether per-layer costs/constraints are needed.

- [Empirical] Verify equilibrium experimentally: for the final s, check best responses by perturbing s_i individually and measuring utility improvements; report how close the learned profile is to a Nash equilibrium.

- [Metrics] Beyond accuracy, measure calibration, robustness to distribution shift/adversarial examples, and uncertainty quality post-pruning to understand broader impacts of equilibrium-driven sparsification.

- [Runtime] Quantify the training/inference overhead of maintaining and updating s variables versus standard pruning pipelines; report wall-clock, memory footprint, and convergence speed.

- [Deployment] Demonstrate actual speed-ups and energy savings on hardware (CPU/GPU/TPU/edge) from neuron/channel pruning, including kernel-level optimizations and memory bandwidth considerations.

- [Thresholding] Sparsity depends on ε=0.01 with no sensitivity study; analyze how ε affects accuracy and measured sparsity and consider learning ε or using hard-thresholded/proximal updates during training.

- [Safety] Track θ magnitudes to prevent compensation effects (large θ with tiny s); incorporate explicit weight decay or constraints on θ norms and assess their impact on equilibrium selection.

- [Dynamics] Consider dynamic regrowth (players re-entering when utility improves) to mitigate premature pruning; compare to dynamic sparse training and study oscillatory behaviors.

- [Initialization] Explore how initialization of s and θ influences equilibrium selection (multi-equilibria) and whether early training (lottery-ticket-style rewinding) improves outcomes.

- [Components] Study interactions with batch norm, layer norm, dropout, residual connections, and mixed-precision training; adapt gate definitions to avoid conflicting scaling effects.

- [Objective] Utilities are tied to training loss; test utilities based on validation loss or task-specific metrics to reduce overfitting-driven pruning decisions.

- [Interpretation] Clarify and reconcile the empirical claim that L2 is “essential” for exact zero participation with established theory that L1 promotes sparsity; offer a theoretical explanation within this specific reparameterization.

- [Robustness] Assess reproducibility across random seeds, datasets, and architectures; report variance in sparsity patterns and accuracy to characterize stability of the equilibrium outcomes.

Glossary

- approximate reconstruction: A technique to reconstruct layer outputs after pruning by solving an approximation problem to preserve performance. "SparseGPT \cite{frantar2023sparsegpt} applies layer-wise pruning with approximate reconstruction to large transformers."

- best response: The strategy that maximizes a player's utility given other players’ strategies in a game. "At equilibrium, each player is playing a best response to the strategies of others."

- best-response dynamics: Iterative updates where each player repeatedly switches to their best response; used to analyze convergence to equilibrium. "We say that an equilibrium is stable if small perturbations decay over time under best-response dynamics."

- best-response mapping: The function that maps others’ strategies to a player’s best response strategy. "Analyzing the Jacobian of the best-response mapping shows that the game exhibits contraction properties when the competition term is not too large"

- bimodal participation distributions: A distribution with two peaks (near zero and one) indicating near-binary inclusion/exclusion of components. "Successful pruning configurations exhibit bimodal participation distributions, with values concentrated near zero or near one."

- competition term: A component in the cost function penalizing correlated parameters to model competitive interactions. "Analyzing the Jacobian of the best-response mapping shows that the game exhibits contraction properties when the competition term is not too large"

- condition numbers: Numerical measures of matrix sensitivity used to assess stability of computations. "Monitoring condition numbers during training provides a practical safeguard against numerical instability"

- contraction properties: Characteristics of a mapping that bring points closer together, implying convergence guarantees. "Analyzing the Jacobian of the best-response mapping shows that the game exhibits contraction properties when the competition term is not too large"

- cross-entropy loss: A standard classification loss measuring the difference between predicted and true distributions. "Network weights are optimized using cross-entropy loss"

- dominated players: Players for whom zero participation yields higher utility, leading them to drop out at equilibrium. "We analyze the resulting game and show that dominated players collapse to zero participation under mild conditions"

- dominated strategies: Strategies that yield lower utility than another strategy (e.g., zero participation), regardless of others’ actions. "A player has a dominated strategy if there exists another strategy (in this case, ) that yields strictly higher utility regardless of what other players do:"

- dynamic sparse training: Training that continually prunes and regrows connections to maintain and adapt sparsity during learning. "Dynamic sparse training \cite{mocanu2018scalable} continuously removes and regrows connections throughout training, maintaining sparsity while adapting topology."

- elastic-net-style regularization: Combined L1 and L2 penalties encouraging both sparsity and stability. "The combined L1+L2 configuration achieves the best accuracy--sparsity balance, consistent with elastic-net-style regularization effects."

- equilibrium-driven pruning: Pruning that emerges naturally as the outcome of equilibrium-seeking dynamics rather than external heuristics. "we derive a simple equilibrium-driven pruning algorithm that jointly updates network parameters and participation variables"

- first-order condition: The equation obtained by setting the derivative of a utility or objective to zero to find optima. "Taking the derivative of the utility function and setting it to zero yields the first-order condition:"

- gradient inner product: The dot product of a parameter vector and the gradient, indicating alignment with loss reduction. "The gradient inner product captures how effectively the parameter group reduces the training loss."

- Hessian: The matrix of second derivatives of a function; used in second-order optimization and sensitivity analysis. "While theoretically grounded, these methods rely on Hessian computations and do not scale efficiently to modern deep networks."

- Jacobian: The matrix of first derivatives describing how a vector-valued function changes with respect to inputs. "Analyzing the Jacobian of the best-response mapping shows that the game exhibits contraction properties when the competition term is not too large"

- layer-wise pruning: Pruning applied independently per layer, often with reconstruction to mitigate accuracy loss. "SparseGPT \cite{frantar2023sparsegpt} applies layer-wise pruning with approximate reconstruction to large transformers."

- low-rank: A matrix approximation technique that reduces dimensionality by representing data with few factors. "LoSparse \cite{li2023losparse} combines low-rank and sparse approximations to compress large models efficiently."

- Lottery ticket hypothesis: The idea that sparse subnetworks found early can train to match dense network performance. "Lottery ticket hypothesis studies \cite{evci2022gradient, zhang2021lottery, chen2021unified} demonstrate that sparse subnetworks can be identified early in training and match dense performance when rewound to initial conditions."

- ℓ0 regularization: A sparsity-inducing approach that penalizes the number of nonzero parameters. "stochastic techniques enable learning sparse structures directly"

- ℓ1 penalty: A regularization term that promotes sparsity by penalizing the absolute values of parameters. "The second term imposes an -style sparsity cost, promoting exact zeros at equilibrium."

- ℓ2 penalty: A regularization term penalizing the squared magnitude of parameters to discourage large values. "The first term penalizes participation scaled by the -norm of the parameter group, discouraging large magnitudes from dominating."

- magnitude-based pruning: Pruning strategy that removes parameters with small absolute values. "Magnitude-based pruning removes parameters with small absolute values, often iteratively combined with fine-tuning"

- multi-layer perceptron (MLP): A feedforward neural network with one or more hidden layers of fully connected neurons. "We use a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) with two hidden layers:"

- Nash equilibrium: A strategy profile where no player can improve their utility by unilaterally changing strategy. "A strategy profile is a Nash equilibrium if no player can improve its utility by unilaterally changing its strategy:"

- non-cooperative game: A game where players make decisions independently to maximize their own utilities. "We model parameter groups such as weights, neurons, or filters as players in a continuous non-cooperative game"

- overparameterized: Having more parameters than necessary, leading to redundancy that can be pruned. "The parameter vector is assumed to be overparameterized, containing redundancy that can be removed without significantly degrading performance."

- participation variables: Continuous gates controlling the extent to which parameter groups contribute to computation. "we associate with every group a participation variable"

- payoff: The utility or reward a player receives based on its strategy and interactions with others. "Each player receives a payoff that balances its contribution to the training objective against the cost of redundancy and competition with other players."

- projected gradient ascent: Gradient ascent with projection onto a feasible set to enforce constraints. "Perform projected gradient ascent on the utilities to move participation variables toward their best responses:"

- quadratic cost structure: A cost function with squared terms modeling penalties like magnitude and competition. "We consider a general quadratic cost structure:"

- redundancy-aware pruning: Pruning that accounts for parameter correlations to remove overlapping functions. "Redundancy-aware pruning emerges from the competition term, which penalizes correlated parameters."

- scalar gates: Single-valued multipliers controlling neuron or parameter group activation in computation. "Participation variables are neuron-level scalar gates learned jointly with network parameters"

- second-order Taylor expansions: Approximations using second derivatives to estimate the impact of parameter changes. "Optimal Brain Damage (OBD) \cite{lecun1990optimal} and Optimal Brain Surgeon (OBS) \cite{hassibi1993optimal} introduced second-order Taylor expansions to quantify the impact of pruning individual weights."

- soft filter pruning: A differentiable pruning method that uses smooth masks to select channels during training. "Soft filter pruning \cite{he2018soft} introduces smooth masking to enable differentiable channel selection during training."

- soft-thresholding: A shrinkage operation that sets small values to zero under L1-like penalties. "The L1 penalty introduces a non-differentiable point at , resulting in a soft-thresholding effect."

- sparsity--accuracy trade-offs: The balance between model sparsity and performance metrics like accuracy. "Experiments on standard benchmarks demonstrate that the proposed approach achieves competitive sparsity--accuracy trade-offs while offering an interpretable, theory-grounded alternative to existing pruning methods."

- stable equilibrium: An equilibrium that resists perturbations, with dynamics returning to it over time. "We show that sparsity emerges naturally as a stable equilibrium of the proposed game."

- strategic interaction: The mutual influence among agents (parameter groups) as they choose strategies affecting each other. "pruning as an equilibrium outcome of strategic interaction among model components."

- structured pruning: Pruning entire units (filters, channels, neurons) to yield hardware-friendly speedups. "Structured pruning removes entire filters, channels, or neurons to enable hardware-friendly acceleration"

- utility function: A function representing a player’s objective, balancing benefits and costs. "Each player seeks to maximize a utility function that captures the trade-off between useful contribution to the learning objective and costs arising from redundancy and competition."

- weight-magnitude and activation-based metrics: Heuristics using weights and activations to rank importance for pruning. "WANDA \cite{sun2023simple} introduces weight-magnitude and activation-based metrics optimized for LLM pruning."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following items outline practical, deployable use cases that leverage the paper’s equilibrium-driven pruning formulation and algorithm. Each item indicates the relevant sector and key assumptions or dependencies affecting feasibility.

- Small/medium-scale model compression in ML engineering (Software)

- What to do: Integrate the equilibrium-driven pruning algorithm as a drop-in optimizer for MLPs/CNNs in PyTorch/TensorFlow to jointly train and prune, then hard-prune parameters with

s_i < ε. - Workflow: Train with participation variables; log utilities and participation histograms; prune at convergence; optionally fine-tune.

- Tools/products: A “ED-Pruner” library; Keras/PyTorch callbacks; “ParticipationViz” dashboards (bimodal participation plots, utility gradients).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires tuning of β (L2) and γ (L1); speedups depend on using sparse kernels or structured pruning; effectiveness is highest on overparameterized models.

- What to do: Integrate the equilibrium-driven pruning algorithm as a drop-in optimizer for MLPs/CNNs in PyTorch/TensorFlow to jointly train and prune, then hard-prune parameters with

- Edge/mobile inference for simple classification tasks (Energy, Robotics, Consumer Software)

- What to do: Compress on-device models (e.g., keyword spotting, digit recognition, sensor event detection) using equilibrium-driven neuron or channel pruning to reduce memory and energy.

- Workflow: Train with participation gates per neuron/channel; export pruned model; deploy with mobile runtimes supporting sparsity or smaller dense models.

- Tools/products: Mobile SDK integration; conversion scripts to ONNX/TFLite; battery/latency monitoring.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Real speedups require structured sparsity or sparsity-aware runtimes; need offline validation of accuracy-sparsity trade-offs.

- Embedded robotics controllers (Robotics)

- What to do: Prune control and perception networks for microcontroller targets to meet real-time constraints.

- Workflow: Apply equilibrium-driven pruning during training; prefer channel/filter-level participation for hardware alignment; deploy on MCU with optimized kernels.

- Tools/products: “Participating Linear/Conv” layers for embedded frameworks; code generation for CMSIS-NN/TVM.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Hardware benefits require structured pruning; verify stability and conditioning (monitor condition numbers as suggested by the paper).

- Data-center energy reporting and MLOps governance (Energy, Software)

- What to do: Add an “equilibrium sparsification” stage to MLOps pipelines; quantify energy saved from smaller models; include participation distribution in model cards.

- Workflow: Joint training+pruning, measure energy/latency, log sparsity and utilities; deploy with sparse runtime if available.

- Tools/products: CI hooks for sparsity metrics; model cards with participation histograms; cost dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Measured energy savings depend on runtime/kernel support; accuracy thresholds must be enforced in production.

- Risk and compliance models on constrained infrastructure (Finance)

- What to do: Use equilibrium-driven pruning to fit models within latency/memory budgets of legacy systems while retaining interpretability via participation variables.

- Workflow: Train with gates; export pruned dense model (or structured sparse model); document retained vs pruned groups as justification.

- Tools/products: Pruning audit reports; utility-based feature/parameter retention explanations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires sector-specific validation and documentation; must adhere to risk thresholds and audit requirements.

- Wearables and point-of-care devices (Healthcare)

- What to do: Prune signal-processing and lightweight diagnostic models for low-power wearables or edge imaging preprocessors.

- Workflow: Equilibrium training with neuron/channel gates; validate clinically; deploy pruned models.

- Tools/products: Edge AI toolchains; clinical validation playbooks including sparsity-accuracy curves.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory validation is required; structured pruning preferred for deterministic latency; robustness/fairness testing needed.

- Teaching and research modules (Education, Academia)

- What to do: Use the framework to teach equilibrium concepts in ML and to design experiments that compare heuristic pruning to game-theoretic pruning.

- Workflow: Classroom demos reproducing MNIST results; extend to other small datasets; analyze bimodal participation distributions.

- Tools/products: Open-source notebooks; visualization dashboards; assignments on best-response dynamics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Best for simple architectures; scaling beyond MLPs requires additional engineering.

- AI energy-efficiency and interpretability audits (Policy)

- What to do: Incorporate participation distributions and sparsity metrics into energy-efficient AI reporting and interpretability audits.

- Workflow: Report equilibrium-induced sparsity, participation histograms, and accuracy impact; compare to magnitude pruning as baseline.

- Tools/products: Standardized metrics and reporting templates; audit checklists incorporating equilibrium criteria.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires policy consensus on metrics; reproducible measurement pipelines.

Long-Term Applications

The following items describe forward-looking opportunities that require further research, scaling, or ecosystem development before they can be broadly deployed.

- Equilibrium-driven pruning for transformers and LLMs (Software)

- What to build: Participation variables at the level of attention heads, MLP channels, and blocks for large transformers; equilibrium utilities incorporating activation statistics and cross-head correlations.

- Tools/products: Layer-wise pruners for LLMs; hybrid with SparseGPT/WANDA; training-time sparsification for finetuning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scaling the utility computation; stability and convergence in deep architectures; hardware/runtime support for structured sparsity; extensive benchmarking.

- Hardware-aligned structured pruning compilers (Energy, Robotics, Semiconductor)

- What to build: Compiler passes that convert equilibrium participation into structured patterns (e.g., channel/filter removal) that map cleanly to GPU/TPU/ANE kernels.

- Tools/products: Integration with TVM, XLA, TensorRT, Core ML; “equilibrium-to-structure” conversion tooling.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Vendor kernel support for sparse/structured ops; reliable mapping from continuous gates to discrete structures with minimal accuracy loss.

- AutoML with equilibrium objectives (Software, Academia)

- What to build: AutoML systems that tune β, γ, η and gating granularity to optimize a multi-objective metric (accuracy, latency, energy, interpretability).

- Tools/products: Hyperparameter tuner with utility-aware search; multi-objective Pareto dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust cross-dataset generalization; efficient evaluation of competition terms; standardized cost/benefit trade-off metrics.

- Federated learning with local equilibrium sparsity (Software, Privacy)

- What to build: On-device participation updates to induce sparsity before aggregation, reducing communication and computation.

- Tools/products: Federated optimizers with joint θ and s updates; secure aggregation compatible with gating.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stability of best-response dynamics across clients; privacy guarantees; heterogeneous device constraints.

- Certified pruning and safety cases (Policy, Safety-Critical Systems)

- What to build: Formal verification of pruning effects and equilibrium stability for models in medical, automotive, and aerospace applications.

- Tools/products: Certification frameworks; conformance tests linking dominated strategies to predictable behavior.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stronger theoretical guarantees and proofs; regulator acceptance; rigorous test suites.

- Adaptive, input-aware sparsity at inference (Energy, Robotics)

- What to build: Runtime gating that adjusts participation s_i based on input difficulty or energy budgets, balancing performance and power dynamically.

- Tools/products: Energy-aware schedulers; real-time utility approximators; gating controllers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Low-latency computation of utility proxies; stability of dynamic gates; hardware support for conditional execution.

- Privacy-aware pruning (Privacy, Policy)

- What to explore: Whether equilibrium-driven elimination of redundant parameters reduces memorization and improves privacy.

- Tools/products: DP-compatible utilities; memorization audits before/after pruning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Empirical validation across tasks; interaction with differential privacy noise and training schedules.

- Model audit and governance platforms (Policy, Software)

- What to build: Governance tools that present player utilities, competition terms, and dominated strategies as part of compliance and explainability.

- Tools/products: “Sparsity Audit” dashboards; policy-friendly summaries of equilibrium outcomes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Agreement on interpretability value of participation metrics; standardized reporting across vendors.

- Game-theoretic NAS and architecture co-design (Academia, Software)

- What to build: NAS methods that favor architectures with stable sparse equilibria (e.g., modular, low-redundancy designs).

- Tools/products: Search spaces augmented with competition penalties; training-time gate simulations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Compute-intensive search; reliable equilibrium proxies; benchmarks demonstrating generalization.

- Domain-specific scientific models (Climate, Energy Grid, Healthcare)

- What to build: Apply equilibrium pruning to large scientific models to reduce footprint while maintaining accuracy for forecasting and diagnostics.

- Tools/products: Sector-specific pruners; validation harnesses for domain metrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Extensive domain validation; careful tuning of penalties to avoid loss of rare-signal capacity.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Scaling beyond MNIST requires careful hyperparameter tuning (β, γ, η), robust optimization schedules, and potentially alternative utility terms tailored to architecture and data.

- Real-world speedups depend on structured sparsity and runtime/kernel support; unstructured sparsity may not yield latency gains without specialized libraries.

- Numerical stability should be monitored (e.g., condition numbers), especially in deeper networks; competition term η may affect convergence and should be controlled.

- Interpretability gains via participation distributions are contingent on clear mapping between parameter groups and functional components (neurons, channels, filters).

- Sector-specific validation (robustness, fairness, safety) is necessary for regulated or safety-critical deployments.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.