An Information Theoretic Perspective on Agentic System Design (2512.21720v1)

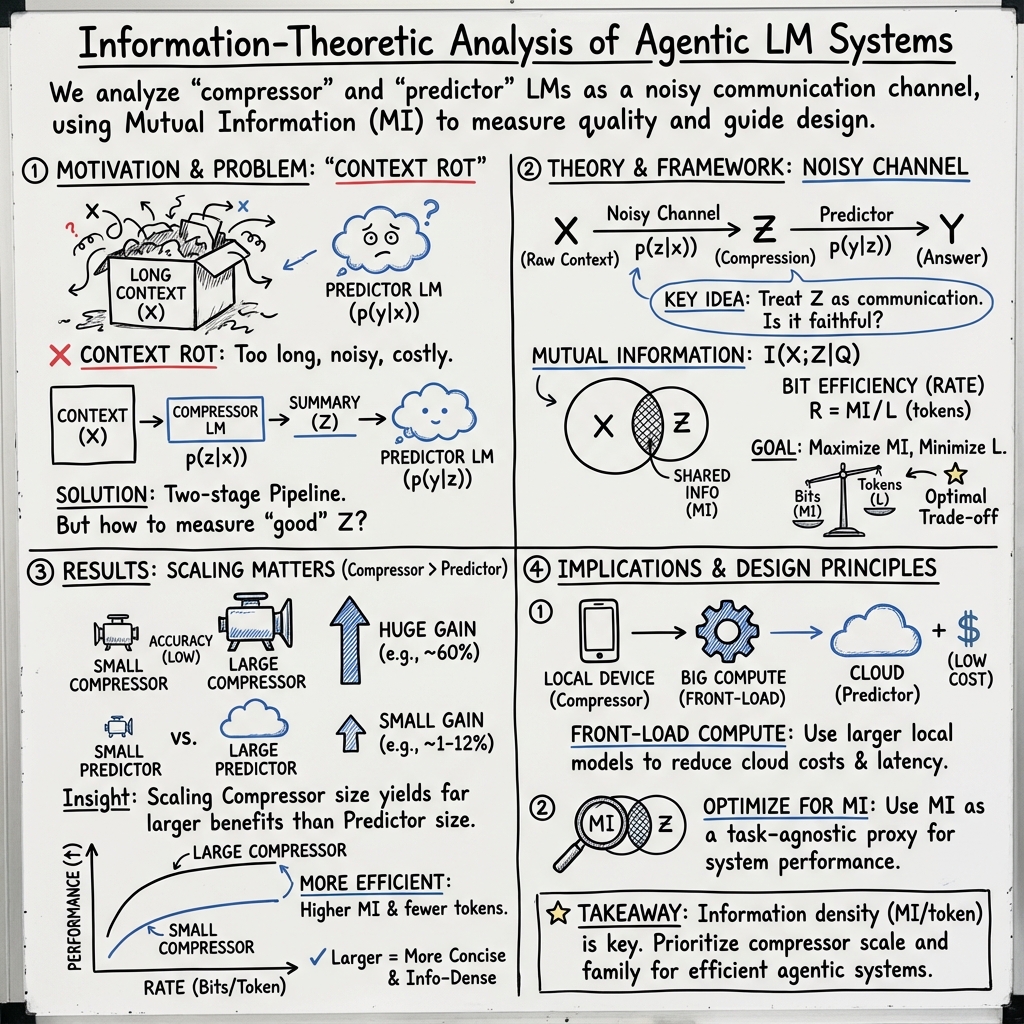

Abstract: Agentic LLM (LM) systems power modern applications like "Deep Research" and "Claude Code," and leverage multi-LM architectures to overcome context limitations. Beneath their apparent diversity lies a recurring pattern: smaller "compressor" LMs (that can even run locally) distill raw context into compact text that is then consumed by larger "predictor" LMs. Despite their popularity, the design of compressor-predictor systems remains largely ad hoc, with little guidance on how compressor and predictor choices shape downstream performance. In practice, attributing gains to compression versus prediction requires costly, task-specific pairwise sweeps. We argue that these agentic system design questions are, at root, information-theoretic. Viewing the compressor LM as a noisy channel, we introduce a simple estimator of mutual information between the context and its compression to quantify compression quality in a task-independent way. We show that mutual information strongly predicts downstream performance, independent of any specific task. Through an information-theoretic framework, we perform a comprehensive empirical analysis across five datasets and three model families. Results reveal that larger compressors not only are more accurate, but also more token-efficient, conveying more bits of information per token. A 7B Qwen-2.5 compressor, for instance, is $1.6\times$ more accurate, $4.6\times$ more concise, and conveys $5.5\times$ more bits of mutual information per token than its 1.5B sibling. Across datasets, scaling compressors is substantially more effective than scaling predictors, enabling larger on-device compressors to pair with smaller cloud predictors. Applied to a Deep Research system, these principles enable local compressors as small as 3B parameters to recover $99\%$ of frontier-LM accuracy at $26\%$ of API costs.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper looks at how to build better AI systems that use more than one LLM (LM) at a time. In many real apps, a smaller model first reads a lot of text and writes a short summary (the “compressor”), and then a larger model reads that summary to answer the question or solve the task (the “predictor”). The authors ask: how do we choose and size these two models so the whole system works best, is cheaper, and uses fewer tokens?

Their big idea: treat the compressor like a messenger in a note‑passing game and measure how much important information the note actually carries. They use an information theory tool called “mutual information” (MI) to score how informative a summary is, in a way that doesn’t depend on any one specific task.

What questions did the researchers ask?

- Is it more helpful to make the compressor bigger or the predictor bigger?

- Which compressors give the most useful information using the fewest words (tokens)?

- Can we predict end‑to‑end performance by directly measuring “how much info” a summary keeps from the original text?

- When tuning a system, which choices matter most: the compressor’s model family, its size, or the predictor’s size?

How did they study it?

The setup: two models, two jobs

- Think of a long document (X), a question about it (Q), and the right answer (Y).

- A smaller “compressor” model turns the long document into a short summary (Z) that is focused on the question.

- A larger “predictor” model reads the summary Z to produce the final answer Y.

Measuring “how much info” a summary keeps (mutual information)

- Mutual information (MI) is a number that says how much the summary Z tells you about the original document X (given the question Q).

- In plain words: the summary should “fit” its source document much better than it “fits” random other documents. If that’s true, MI is high.

- They estimate MI using the probabilities exposed by today’s LM servers. No extra training is needed.

Two related ideas:

- Information rate (or “bit efficiency”): MI per token. This tells you how much useful info each token in the summary carries.

- Rate–distortion: a classic idea linking “how much info you keep” (rate) to “how many mistakes you make” (distortion). Here, fewer mistakes = higher accuracy.

What they tested on

- They ran lots of experiments across five datasets (health reports, finance filings, scientific papers, chats, and web pages).

- They tried several model families and sizes for both compressors (smaller models) and predictors (larger models).

- They tracked accuracy, token counts, and compute cost (how much computer work the models do).

What did they find, and why is it important?

Here are the main results in simple terms:

- Bigger compressors help more than bigger predictors.

- Making the compressor larger boosted accuracy a lot (for example, going from a 1–1.5B to a 7–8B compressor raised accuracy by up to around 60% on a health dataset).

- Making the predictor larger (e.g., 70B to 405B) helped only a little (often under ~12%).

- Bigger compressors write shorter, better summaries.

- They used fewer tokens while keeping or improving quality—up to about 4.6× more concise in one family.

- Because summaries are shorter, total compute per generation grows slower than model size. In one case, moving from a 1.5B to a 7B compressor added only ~1.3% more compute per generation.

- Bigger compressors pack more information into each token.

- MI went up with compressor size, and MI per token (information rate) also went up.

- In one example (Qwen‑2.5 family), the 7B compressor was about 1.6× more accurate, 4.6× more concise, and carried ~5.5× more bits of information per token than the 1.5B version.

- Information rate strongly predicts performance.

- Information rate (bits per token) correlates closely with end‑to‑end accuracy and with perplexity (a common language modeling score).

- Translation: you can often forecast system quality just by checking how informative the summaries are, without running the full task pipeline.

- Which knobs matter most?

- The compressor’s model family mattered the most, then the compressor’s size, then the predictor’s size.

- Predictors don’t need to match the compressor’s family to work well.

- Real system win: frontier‑level accuracy at a fraction of the cost.

- In a “Deep Research” setup, local compressors as small as ~3B recovered about 99% of a top model’s accuracy at roughly a quarter of the API cost.

Why this matters: If you’re building an AI that must read lots of text (long PDFs, web pages, logs), the smart move is to invest in a stronger compressor that creates short, information‑dense summaries. That saves tokens, lowers cloud costs, and keeps accuracy high.

What could this change?

- Put more power on the device you control. Run a stronger compressor locally (e.g., on a laptop). This reduces how much you need from expensive cloud predictors.

- Use MI as a quick, task‑agnostic health check. If the compressor’s MI (and MI per token) rises, the whole system likely gets better—even before you run end‑to‑end tests.

- Pick compressor family carefully. Model family differences change how well information scales and how concise summaries are.

- Expect better efficiency as compressors grow. Larger compressors don’t just “memorize more”—they communicate more useful info in fewer tokens.

A few simple takeaways

- Make the compressor bigger first; it usually matters more than making the predictor bigger.

- Aim for summaries that are short but packed with useful info (high information rate).

- You can often run stronger compressors on modern laptops, cutting cloud costs.

- Use mutual information to estimate summary quality without tying yourself to any specific task.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The paper introduces an information-theoretic framework and an MI estimator for compressor–predictor systems, but several aspects remain missing or underexplored. Future work could address the following:

- Formal statistical properties of the MI estimator:

- Prove unbiasedness/consistency, derive variance, confidence intervals, and sample complexity requirements for the Monte Carlo estimator under autoregressive LMs.

- Analyze the impact of finite-sample bias and the practice of clipping negative MI estimates to zero on estimator reliability.

- Quantify robustness to LM calibration errors (observed at 1–3B scales) and establish calibration procedures that reduce estimator variance.

- Proxy-model dependence and evaluation fidelity:

- Characterize and correct bias introduced by using cross-family proxy models to score p(z|x), versus using the compressor’s own probabilities.

- Standardize MI estimation across inference engines with differing log-prob APIs and tokenization schemes to ensure reproducibility.

- Theoretical grounding of rate–distortion fits:

- Replace empirical exponential fits with theoretically justified models for discrete, non-Gaussian language sources and autoregressive channels.

- Derive task- and dataset-dependent rate–distortion functions and identify conditions where predictor scaling can overcome compressor bottlenecks.

- Choice of information quantity:

- Compare I(X;Z|Q) to more task-relevant alternatives like I(Y;Z|Q) (information about the answer) and assess which better predicts downstream utility.

- Evaluate MI of structured outputs (key–value extractions, function calls, DSLs) versus free-form text compressions.

- Dataset scope and generality:

- Extend beyond QA/extractive/perplexity settings to code generation, multi-step reasoning, planning, tool-use, long-horizon tasks, and multimodal inputs.

- Test cross-lingual and cross-domain generality (legal, medical, scientific, noisy web text) and the effect of corpus heterogeneity on MI saturation.

- Multi-turn and multi-agent communication:

- Develop MI estimators for iterative, multi-round protocols and multi-agent topologies; measure cumulative MI across turns and quantify information loss or redundancy.

- Analyze how aggregation strategies (e.g., merging multiple compressions) affect rate–distortion and the optimal communication schedule.

- Retrieval integration:

- Incorporate retrieval quality explicitly into the framework (e.g., model X as retrieved context R(X0) and quantify MI loss due to retrieval errors).

- Design compression policies conditional on retrieval uncertainty and evaluate joint retrieval–compression optimization.

- Tokenization and length effects:

- Control for tokenizer differences across model families when comparing “bit efficiency per token” and assess sensitivity to prompt-driven verbosity constraints.

- Normalize MI-per-token across tokenizers (byte-level vs. subword) to yield fair cross-model comparisons.

- Compute-cost modeling and deployment realism:

- Replace simplified FLOPs-per-generation with latency/energy models that incorporate memory bandwidth, quantization, kernel fusion, batching, and device-specific optimizations.

- Evaluate on-device constraints (battery, thermal limits, privacy/security) and end-to-end pipeline costs (including retrieval, orchestration, and network overhead).

- Predictor–compressor compatibility:

- Investigate whether predictors have latent preferences for compression styles (format, structure, level of abstraction) and how to measure/align them.

- Study end-to-end co-design: fine-tune compressors to maximize predictor utility under rate constraints rather than raw MI.

- Training objectives and optimization:

- Develop learning objectives grounded in rate–distortion (e.g., penalize distortion at fixed MI rate) and train compressors end-to-end with predictors.

- Explore contrastive/variational MI estimators (InfoNCE, CPC) as training signals, benchmarking stability, bias, and sample efficiency.

- Mixture-of-experts (MoE) and reasoning-enhanced LMs:

- Systematically analyze MI and compute scaling for MoE models, accounting for active experts per token and dynamic routing.

- Extend to chain-of-thought/plan-based compressors and quantify information carried by reasoning traces versus final summaries.

- Error analyses tied to MI:

- Relate compressor failure modes (incorrect answer, no answer, missing details) to MI levels; determine when high MI still yields wrong answers and why.

- Build diagnostics that disentangle “information retained” from “information useful for prediction,” guiding targeted compressor improvements.

- Normalization and comparability of MI:

- Address the estimator’s dependence on the number of documents N (upper bound at log N) and provide normalized MI metrics enabling cross-dataset comparisons.

- Investigate MI saturation behavior on heterogeneous corpora and how to distinguish estimator ceiling effects from genuine capacity limits.

- Scalability of MI computation:

- Reduce the O(N2) evaluation burden of computing E_{x'}[p(z|x')] via sampling, caching, or importance weighting, while preserving estimator fidelity.

- Provide practical guidelines for choosing N and M (number of contexts and compressions per context) under compute budgets.

- Evaluation methodology:

- Validate accuracy judgments beyond GPT-4o-mini judges, including human evaluation and multiple independent LMs to reduce judge bias.

- Report sensitivity analyses for prompt templates, seed variability, and predictor choice to quantify uncertainty in conclusions.

- Security, privacy, and robustness:

- Analyze risks of local compression (data exfiltration, adversarial perturbations) and propose secure channel designs (encryption, authenticated formats).

- Evaluate robustness of compressors to adversarial or noisy inputs and quantify the effect on MI and downstream distortion.

- Practical system design principles:

- Identify the minimal predictor capacity required per task/domain and conditions where predictor scaling begins to meaningfully reduce distortion.

- Develop adaptive routing/fallback policies: when to bypass compression and send raw context, based on estimated MI, rate, cost, and task difficulty.

Glossary

- Agentic LLM (LM) systems: Multi-model AI pipelines where LLMs act, plan, and communicate to accomplish tasks. "Agentic LLM (LM) systems power modern applications like “Deep Research” and “Claude Code,” and leverage multi-LM architectures to overcome context limitations."

- Bit-efficiency: The amount of mutual information conveyed per output token; synonymous with information rate. "We define rate (or bit-efficiency) as"

- Conditional mutual information: The mutual information between variables given a conditioning variable (here, between context and compression given a query). "Thus, each compression is generated conditioned on the query , so we estimate "

- Context rot: Degradation of model performance as context grows or quality declines beyond effective handling. "degrading model performance---a failure mode referred to as context rot"

- Control plane and data plane: Architectural split where smaller models process raw inputs (data plane) and larger models coordinate and decide (control plane). "effectively splitting the control plane and the data plane"

- Distortion: Error in the prediction within rate–distortion theory; often related to 1 − accuracy. "Rate-distortion theory quantifies the trade-off between rate---i.e., the amount of information the compression carries about the input---and distortion---the error in the prediction."

- Exponential-decay functions: Functional form used to fit rate–distortion relationships, showing diminishing returns with increased rate. "we fit decaying exponential functions to the rate-distortion data"

- FLOPs-per-generation: Compute cost measured as floating-point operations required to generate a model’s output. "This token-efficiency yields sublinear scaling of FLOPs-per-generation as a function of model size."

- FP16 precision: Half-precision floating point format used to reduce memory and compute in model inference. "under FP16 precision with memory estimates from Modal"

- Frontier-LM: The highest-performing, cutting-edge LLMs. "Applied to a Deep Research system, these principles enable local compressors as small as 3B parameters to recover of frontier-LM accuracy at of API costs."

- GFLOPs-per-compression: Billions of floating-point operations needed specifically for the compression step. "(Right) GFLOPs-per-compression."

- Information bottleneck principle: Theory that optimal representations compress input while retaining task-relevant information. "According to the information bottleneck principle, latent representations in graphical models trade-off input compression and downstream prediction (``compress as much as possible while being able to do the task'')"

- Information density: The concentration of task-relevant information per token in generated text. "This suggests that increased model capacity and intelligence doesn't only materialize itself as greater memorization \citep{morris2025languagemodelsmemorize}, but also as information density."

- Information rate: Mutual information per token; a measure of communication efficiency between compressor and predictor. "Information rate (bit-efficiency) is closely related to distortion (1 accuracy)."

- KL divergence: A measure of divergence between probability distributions, used here to express mutual information. "we start with the KL divergence \citep{kullback1951information} representation:"

- Logistic regression: A generalized linear model used to predict binary outcomes (e.g., correctness) from system features. "We fit a logistic regression predicting binary correctness on LongHealth and FinanceBench using the features specified in Appendix~\ref{sec:appendix-glm-analysis}."

- Miscalibration: Model likelihoods poorly reflecting true probabilities, leading to errors like high confidence in nonsensical sequences. "we find that LMs at 1--3B could assign high likelihoods to nonsensical token sequences, indicating miscalibration."

- Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models: Architectures that route inputs to specialized expert subnetworks to improve efficiency and capacity. "mixture-of-experts (MoE) models \citep{fedus2022switch} may exhibit different scaling behaviors since their compute cost depends on activated experts rather than total parameter count."

- Monte Carlo estimator: A sampling-based method to approximate quantities like mutual information from model likelihoods. "In practice, our Monte Carlo estimate can produce small negative values due to finite-sample variance."

- Mutual information (MI): A measure of how much information one variable contains about another; here, how much the compression preserves from the context. "We propose using mutual information (MI) between the raw context and its compression as a task-agnostic proxy of compressor efficacy---analogous to how perplexity serves as a task-agnostic proxy of downstream performance"

- Noisy channel: A communication model where transmitted signals are corrupted; used to conceptualize compressor outputs. "viewing the compressor as a noisy channel between the raw data and the predictor model."

- Perplexity: A standard metric of LLM performance reflecting the average uncertainty over tokens. "mutual information is also strongly correlated with perplexity (, )"

- Predictor LM: The model that consumes compressed summaries to produce final answers or outputs. "which a predictor ingests to extract the final answer ."

- Proxy model: An auxiliary model used to estimate quantities (e.g., log probabilities) when the original model is impractical. "In the bulk of our work, we use proxy models at the 7--8B scale of a different model family."

- Quantization: Reducing numeric precision of model parameters to lower memory and compute costs. "powerful models up to 27B can run without aggressive quantization on current-generation laptops."

- Rate-distortion analysis: Study of the trade-off between information rate and prediction error to characterize system performance. "we then conduct a rate-distortion analysis to measure how downstream task performance varies with the degree of compression."

- Rate-distortion curves: Plots showing how distortion changes with the information rate under different model settings. "We plot the resulting rate-distortion curves across predictor sizes 1B, 8B, 70B, and 405B for Llama compressors on LongHealth."

- SGLang: An accelerated inference engine enabling efficient log-probability access without full vocabulary distributions. "which allows us to use accelerated inference engines such as SGLang \citep{zheng2024sglang}."

- Token-efficiency: Achieving more informative outputs with fewer tokens, improving compute and communication efficiency. "Results reveal that larger compressors not only are more accurate, but also more token-efficient, conveying more bits of information per token."

Practical Applications

Below are actionable, real-world applications that follow directly from the paper’s findings and methods. Each item is categorized as immediate (deployable now) or long-term (requiring further development), linked to relevant sectors, and includes assumptions or dependencies that may affect feasibility.

Immediate Applications

These can be implemented today using the paper’s estimator, scaling principles, and compressor–predictor design guidance.

- MI-based compressor quality meter for model selection and A/B testing (Software, MLOps)

- What: Deploy the paper’s mutual information (MI) estimator to score compressions task-agnostically and select the best compressor (e.g., Qwen-2.5 7B vs 1.5B) before any end-to-end evaluation.

- Workflow/Product: “MI Meter” CLI/SDK integrated into inference servers (e.g., SGLang) and MLOps dashboards for agentic pipelines.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to token-level log probabilities; proxy-model use can introduce small biases; single-round GPT-style compression (non-reasoning) is the tested setting.

- Front-load compute: run larger compressors locally, pair with smaller cloud predictors (Enterprise software; Cloud–Edge; Finance; Healthcare)

- What: Adopt the principle that scaling compressors yields larger accuracy gains and sublinear FLOPs-per-generation, enabling local 3–7B compressors with smaller cloud predictors.

- Workflow/Product: Edge Compressor service (Ollama/llama.cpp) on laptops/phones, cloud predictor orchestrator; budget-aware selection of compressor–predictor pairs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Device RAM/VRAM sufficient for 3–7B models under FP16/quantization; robust local runtime; tokenization compatibility; stable network to cloud predictor.

- Cost-optimized Deep Research pipelines (Education; Enterprise research; Knowledge work)

- What: Use multiple local compressors to summarize web/search results and aggregate with a single cloud predictor, achieving ~99% of frontier-LM accuracy at ~26–28% cost vs uncompressed baseline.

- Workflow/Product: “Deep Research Lite” that schedules local compressions, aggregates summaries, and gates escalations; integrates with GPT-4o or Llama predictors.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable search/scrape and dedup; prompt hygiene; RACE-style evaluation may vary by domain.

- MI-threshold gating and fallback routing (Software; Operations; Reliability engineering)

- What: Set MI-per-token thresholds to decide when to re-compress, switch to a bigger compressor, or escalate to full-context remote processing.

- Workflow/Product: Compressor Router component that monitors MI and bit-efficiency and triggers fallbacks; integrates with retry policies and cost SLAs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: MI estimator stability across domains; variance in MI for small models; latency budget for re-compression.

- Prompt-level conciseness control with preserved performance (All sectors using LMs)

- What: Enforce compression length targets (e.g., 3/6/9 sentences) while maintaining accuracy and MI; reduce tokens and FLOPs with negligible loss.

- Workflow/Product: “Concise Compression” prompt templates embedded in agent frameworks (OpenAI, Anthropic, vLLM, SGLang).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Model family differences in conciseness compliance (Qwen-2.5 > Llama/Gemma observed); task-specific tolerance for brevity.

- MI as a proxy for extractive quality/perplexity monitoring (Data pipelines; Content moderation)

- What: Use MI to predict perplexity/quality for extractive tasks on large corpora (e.g., FineWeb), enabling early QA without labeled data.

- Workflow/Product: “MI-based Quality Monitor” for content ingestion, summarization, and QA pipelines.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Strong negative correlation (r ≈ −0.84) shown for extractive tasks; task transferability should be validated.

- Cross-family pairing confidence (Procurement; Architecture design)

- What: Pair compressors and predictors across families (e.g., Qwen compressor with Llama predictor) without performance penalty; prioritize compressor family/size over predictor scaling.

- Workflow/Product: Architecture advisor in platform tooling that proposes cross-family pairings.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Observed on GPT-style non-reasoning LMs; may differ for specialized reasoning/MoE architectures.

- Edge privacy-by-design for regulated documents (Healthcare; Finance; Legal)

- What: Compress PHI/PII locally to minimize cloud data exposure and token volume while preserving answerability.

- Workflow/Product: HIPAA/GDPR-aware local summarization gateways that redact or abstract sensitive details before cloud inference.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Proper redaction policies; secure local storage; legal review; audit trails and consent tracking.

- Energy and cost-aware compute planning (Energy; IT procurement; Sustainability)

- What: Exploit sublinear FLOPs-per-generation with larger compressors (e.g., Qwen-2.5 1.5B→7B adds ~1.3% FLOPs) to reduce datacenter spend and energy usage per task.

- Workflow/Product: “Rate–FLOPs Planner” tool for capacity planning and budget allocation in agentic workflows.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Real device-level efficiency varies; model family/token-length effects; amortized overheads.

- Domain applications with demonstrated gains (Sector-specific workflows)

- Healthcare (LongHealth): On-device compression of long patient histories for cloud QA; triage and clinical note summarization with MI-based gating.

- Finance (FinanceBench): Compress 10-K filings locally and answer risk/compliance questions; faster due diligence pipelines.

- Academia (QASPER): Summarize long papers locally; answer research questions through a smaller cloud predictor; MI-based query-aware compression.

- Daily Life: Browser extension that summarizes pages locally, then queries a cloud assistant; email/meeting notes summarization with MI-based quality checks.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Dataset/document heterogeneity influences MI saturation; task robustness and correctness require careful prompt/guardrails.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling, standardization, or integration beyond current capabilities.

- MI- and rate–distortion-aware training objectives for compressors (Software; ML research)

- What: Train compressors to maximize MI-per-token under task constraints, using contrastive/variational objectives (e.g., InfoNCE) or regularization guided by rate–distortion.

- Tools/Products: “MI-Optimized Compressor” training recipes and libraries; benchmarks with MI/bit-efficiency metrics.

- Dependencies: Stable high-dimensional MI estimators; scalable training datasets; evaluation standardization.

- AutoML for agentic architecture search using MI (MLOps; Platform tooling)

- What: Automate selection of compressor family/size, predictor size, conciseness targets, and routing thresholds based on MI and bit-efficiency curves.

- Tools/Products: “Agent Architect” optimizer that learns rate–distortion frontiers per domain.

- Dependencies: Multi-objective optimization at scale; robust MI estimation under diverse workloads.

- Multi-turn, multi-agent communication optimization via information theory (Software; Robotics)

- What: Extend MI-based analysis to iterative planning, tool use, and sensor-to-language compression for embodied systems; optimize communication rounds and agent roles.

- Tools/Products: “InfoFlow Planner” for multi-agent orchestration (planning depth, rounds, handoffs).

- Dependencies: MI estimation across dialogue turns; modeling of tool and memory channels; evaluation in dynamic environments.

- Privacy-preserving compression with formal guarantees (Policy; Compliance; Security)

- What: Combine MI limits with differential privacy, redaction, and semantic abstraction to provide measurable privacy guarantees for on-device compression.

- Tools/Products: “Compliance Guard” with MI auditing, DP noise calibration, and legal reporting for HIPAA/GDPR/SOX.

- Dependencies: Legal acceptance of MI/DP metrics; standardized audit processes; domain-specific risk models.

- Interoperability standards for compressor–predictor protocols (Standards; Ecosystem)

- What: Define APIs and metadata for compressed artifacts (e.g., MI score, length budget, domain tags) to interoperate across vendors and model families.

- Tools/Products: Open standard similar to model cards but for compressed contexts; reference implementations.

- Dependencies: Industry consensus; governance; versioning and security models.

- Energy/green AI optimization via bit-efficient communication (Energy; Cloud economics)

- What: Use MI-per-token as an efficiency target in datacenter scheduling; incentivize bit-efficient compressions to reduce energy per solved task.

- Tools/Products: “Green Compression” schedulers; billing tiers that reward smaller token footprints at adequate MI.

- Dependencies: Reliable metering; alignment with cloud provider pricing; lifecycle footprint accounting.

- Hardware–software co-design for local 7B–27B compressors (Edge computing; Devices)

- What: Build NPUs/accelerators and memory pipelines tailored for compressor workloads with MI-aware scheduling; run larger models on consumer devices.

- Tools/Products: Device firmware and runtimes optimized for compression throughput/latency; pre-loaded domain compressors.

- Dependencies: Hardware roadmap; thermal/power constraints; quantization and caching strategies.

- Sector-specific MI benchmarks and regulation readiness (Policy; Sector governance)

- What: Establish MI-based evaluation regimes for high-stakes domains (clinical QA, financial compliance) to certify compression quality before deployment.

- Tools/Products: Domain test suites with MI/performance thresholds; regulator-ready reporting formats.

- Dependencies: Stakeholder agreement; validation against human outcomes; mitigation of estimator variance.

- Pricing models and SLAs based on “information rate” rather than tokens (Cloud platforms; Economics)

- What: Move from token-count billing to MI/bit-efficiency-aware SLAs to better align cost with effective information transfer.

- Tools/Products: “InfoRate” billing APIs; dashboards showing MI and downstream accuracy guarantees.

- Dependencies: Standardized MI measures; platform adoption; customer education.

- Domain-tailored compressor fine-tuning for heterogeneous corpora (Healthcare; Finance; Law; Education)

- What: Fine-tune compressors to achieve early MI saturation on domain-specific documents (e.g., structured 10-Ks vs unstructured clinical narratives) to improve bit-efficiency and accuracy.

- Tools/Products: “Domain Compressor Packs” with curated prompts and adapters.

- Dependencies: High-quality labeled/unlabeled corpora; evaluation pipelines; continual learning strategies.

Notes on assumptions and dependencies that cut across items:

- The MI estimator demonstrated is practical and unbiased in the paper’s scope but can show small negative values due to finite-sample variance; clipping is used.

- Findings primarily hold for GPT-style non-reasoning architectures with single-round compression; extensions to reasoning/MoE and multi-turn settings are promising but need further validation.

- Model-family differences (e.g., Qwen-2.5 vs Llama vs Gemma-3) matter; token efficiency and MI scaling vary across families and datasets.

- Edge deployment feasibility depends on device capability, quantization, and runtime (Ollama/llama.cpp); production reliability requires robust telemetry and guardrails.

- Regulatory gains (HIPAA/GDPR) from local compression depend on correct handling of PHI/PII, secure storage, auditability, and legal review.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.