- The paper demonstrates robust integration of hBN-encapsulated graphene Josephson junctions into 3D copper cavities for both single- and two-qubit devices.

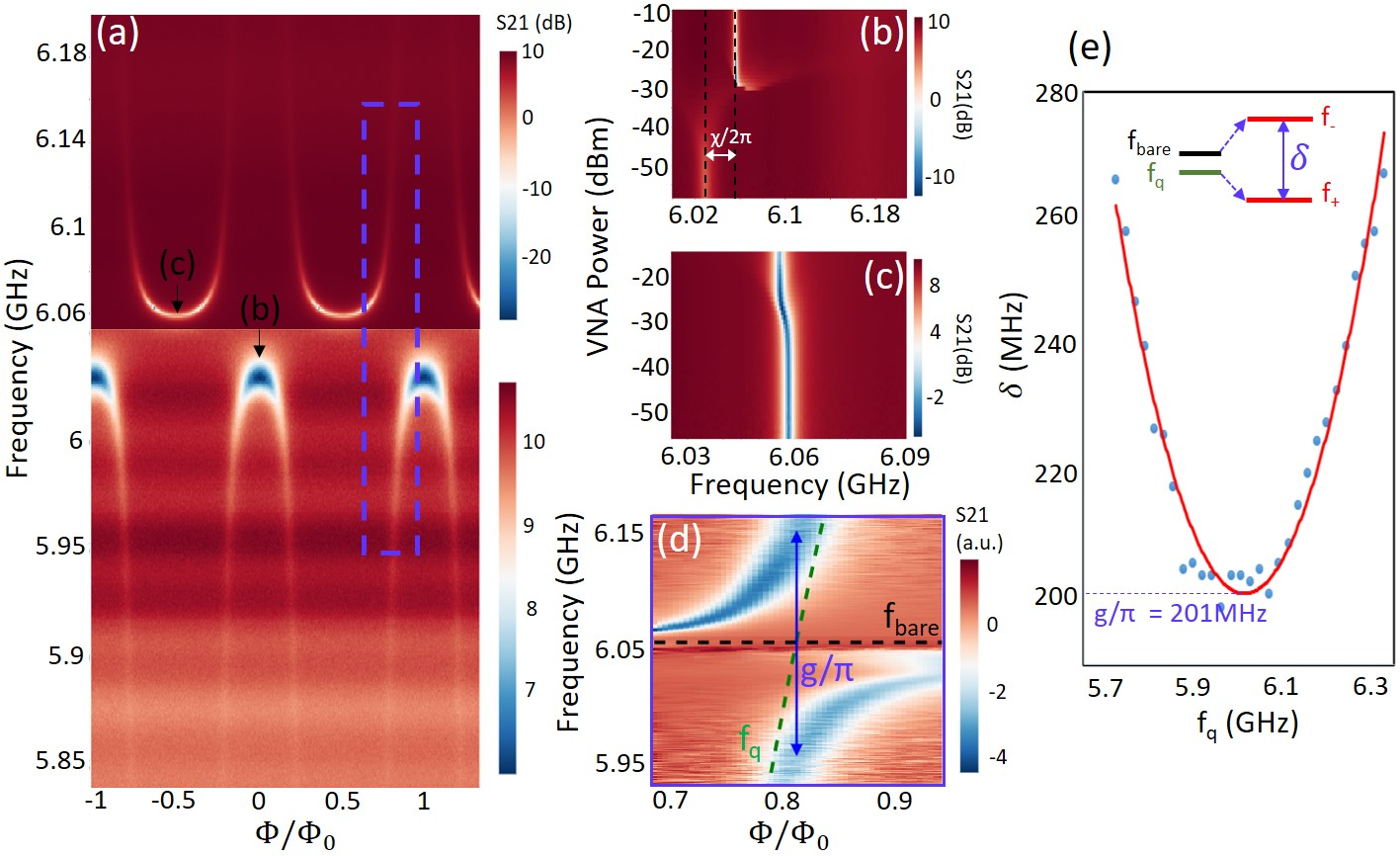

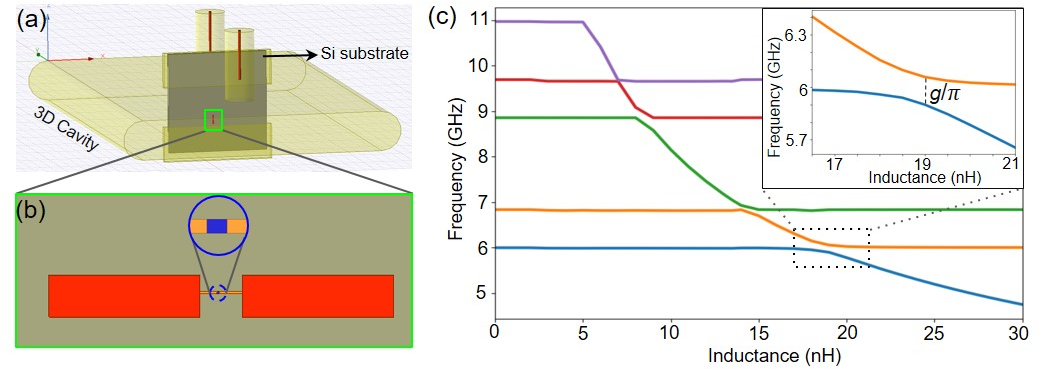

- It employs flux-tunable and fixed-frequency qubit designs, revealing clear vacuum Rabi splitting and dispersive shifts under varying coupling regimes.

- The study quantifies decoherence mechanisms and noise sensitivity, offering actionable insights for optimizing device performance and scalability.

3D Cavity-Coupled Graphene-Based Superconducting Quantum Circuits: Single- and Two-Qubit Architectures

Introduction

This work presents the fabrication, integration, and characterization of graphene-based superconducting quantum circuits embedded in three-dimensional (3D) copper cavities. It demonstrates both single-qubit and two-qubit device architectures, employing hexagonal boron nitride (hBN)-encapsulated graphene Josephson junctions (JJs) interfaced with niobium-titanium contacts. The devices leverage cQED for microwave control and readout. A detailed analysis focuses on the coupling regimes accessible by loading the same chips into cavities of varying resonant frequencies, exhaustively characterizing flexibly tunable coupling between 2D-material-based superconducting qubits and 3D microwave environments.

Figure 1: Optical micrograph of the two-qubit graphene-based superconducting quantum circuit coupled to a 3D copper cavity. The device features both a SQUID-based (Q1) and a fixed-frequency single-JJ (Q2) qubit.

Device Architecture, Fabrication, and Measurement Setup

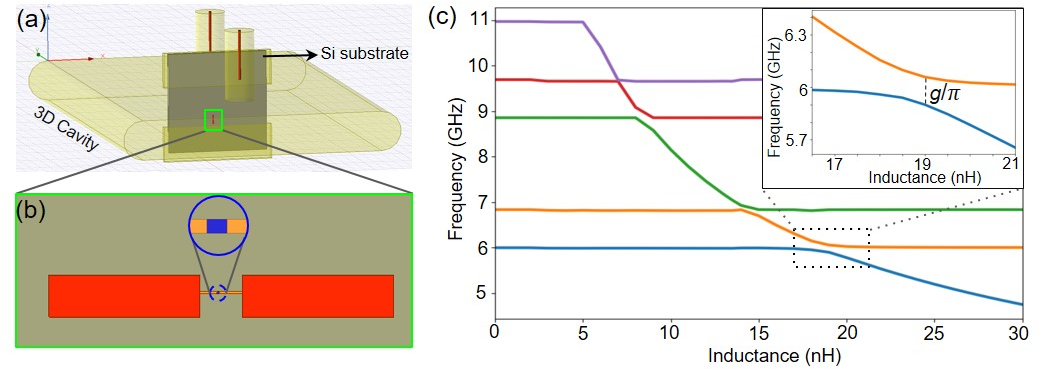

The devices comprise hBN/graphene/hBN stacks on Si/SiO2 substrates, with graphene weak links defined by electron-beam lithography and reactive-ion etching. Edge contacts are realized by subsequent NbTi sputtering, ensuring high interface transparency. Two device types are studied: one with a flux-tunable SQUID-based qubit and another with a SQUID and independently addressable single-JJ transmon (Figure 1).

The microwave environment consists of a two-port 3D copper cavity allowing precise tuning of external Q factors and qubit-cavity geometric coupling. Qubits are capacitively coupled to the cavity mode via designed electrode geometries. Experimental setups enable frequency-domain (power dependence, flux modulation, spectroscopy) and time-domain (relaxation, decoherence) characterization at 10 mK.

Figure 2: Optical microscope images of device 1 at various fabrication stages, with red regions denoting graphene weak links and blue for superconducting contacts.

Single-Qubit Spectroscopy: Coupling Regimes and Coherence

Systematic measurement of the single SQUID-based qubit demonstrates both strong-coupling and dispersive regimes—achieved by varying cavity resonance and qubit frequency via magnetic flux. Characteristic vacuum Rabi splitting is observed at zero detuning, with extracted coupling strength g/2π=100.5 MHz, well above both cavity decay κ and qubit relaxation γ rates.

Figure 3: Flux- and power-dependent S21 cavity response of the SQUID-based single-qubit device. Vacuum Rabi splitting is evident at resonance.

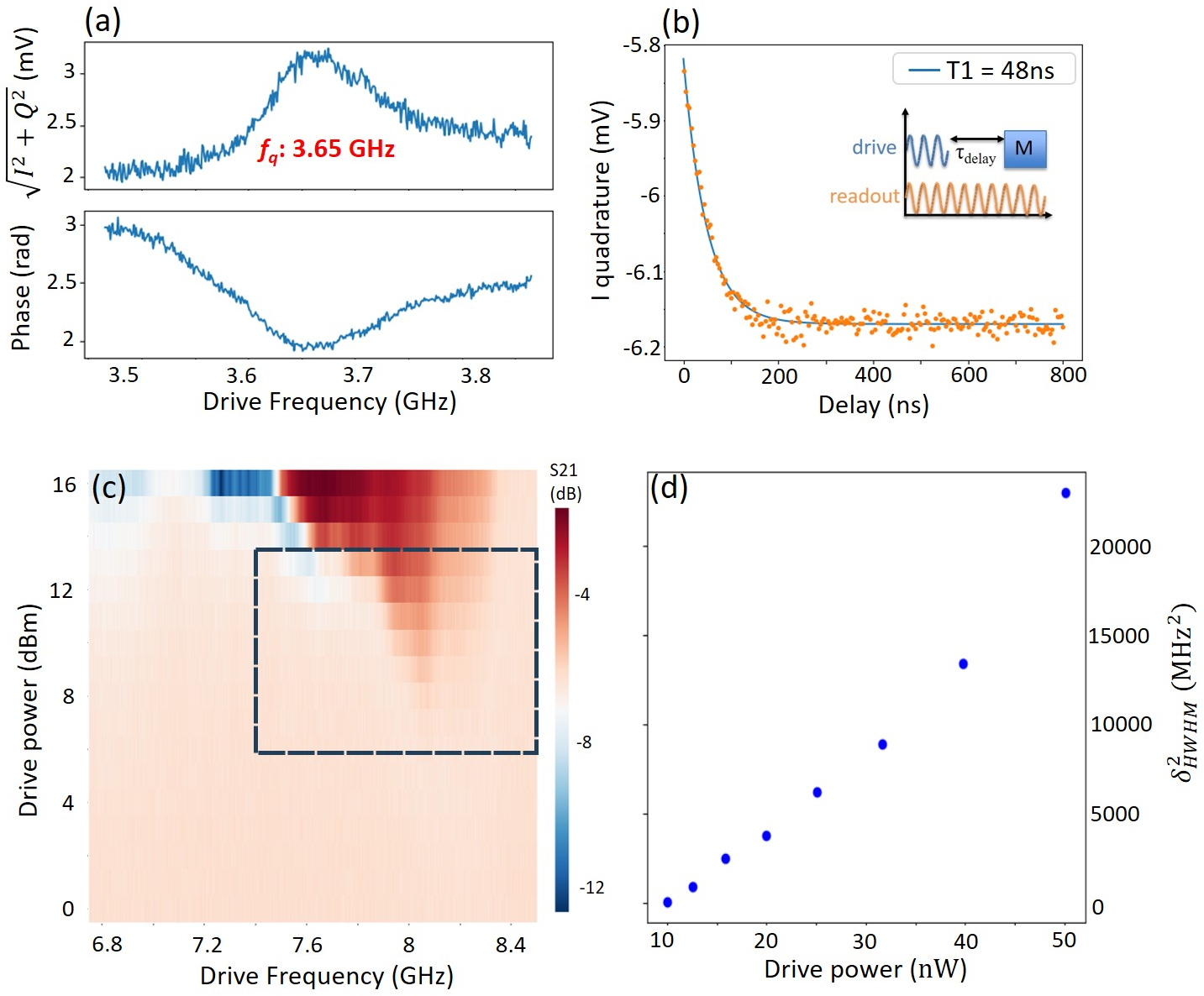

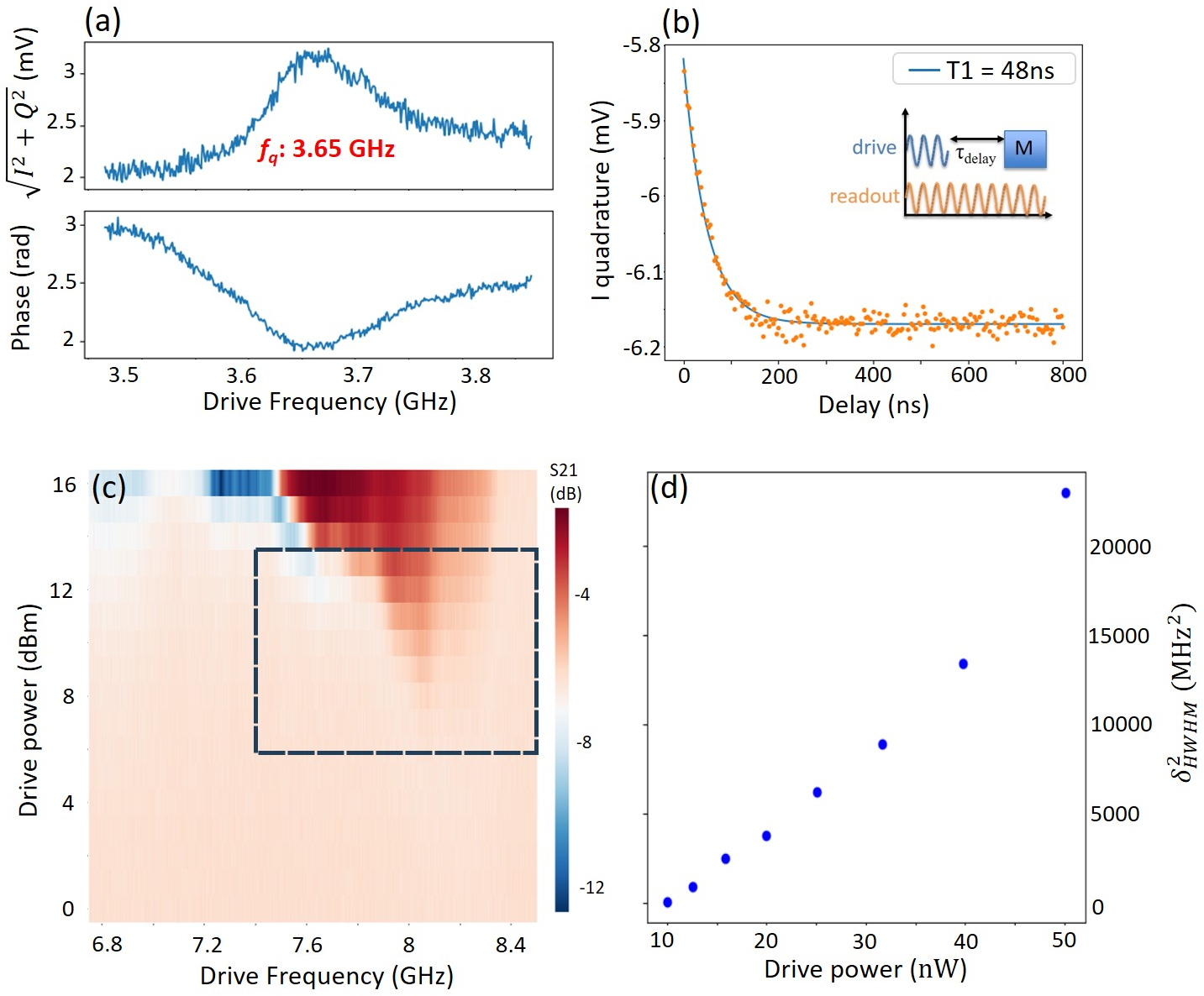

Two-tone spectroscopy under continuous-wave drive reveals a maximum qubit frequency fq,max≈6.43 GHz (cooldown 2), in good agreement with estimates obtained from the dispersive shift χ and g. Direct quantification of the coherence properties via linewidth analysis yields a relaxation time T1≈48 ns and a lower bound for the dephasing time T2∗≳17.6 ns at the flux-insensitive sweet spot. Notably, away from this optimal point, the linewidth broadens sharply with increasing ∣dfq/dΦ∣, implicating low-frequency flux noise as the dominant decoherence mechanism (driven by the enhanced sensitivity of the transition frequency to magnetic flux).

Figure 4: Flux-dependent cavity response and two-tone qubit spectroscopy, indicating tunability and distorted spectral region due to drive-cavity proximity.

Figure 5: Power dependence, flux tuning, and two-tone qubit transition spectrum for the SQUID-based device. Analysis of linewidth (d) establishes correlation to ∣dfq/dΦ∣ (flux noise sensitivity).

This noise sensitivity is quantified by estimating the amplitude of flux fluctuations, which is found to be several orders of magnitude above conventional aluminum-based transmons, identifying an area for further improvement in 2D material qubit platforms.

Two-Qubit Architectures: Dispersive Readout and Coupling Analysis

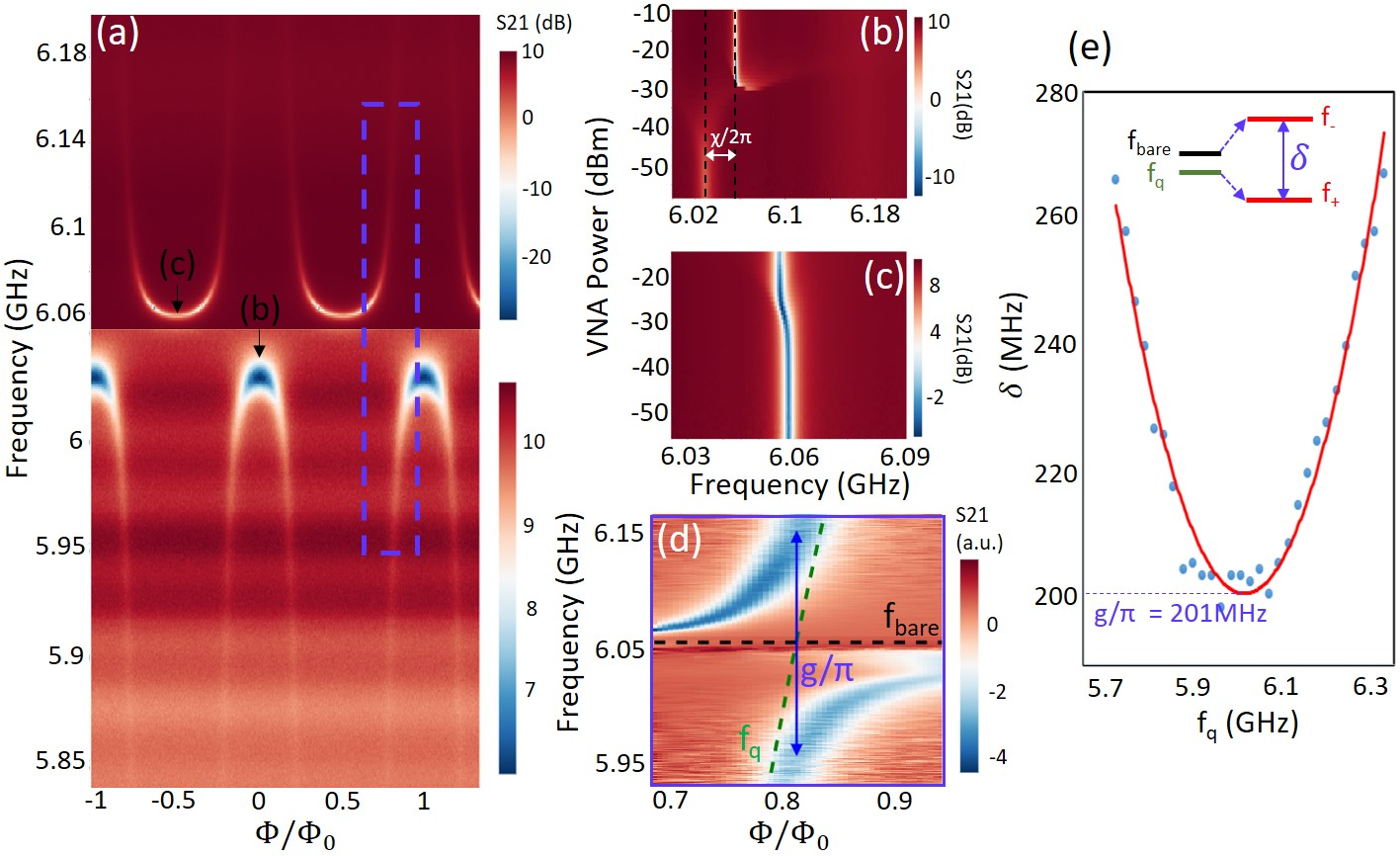

The two-qubit device integrates a SQUID-based qubit and a single-JJ transmon with differing geometric and Josephson parameters, both coupled to a common cavity mode. The system is probed in cavities of varying frequency across multiple cooldowns, thus sampling regimes of positive and negative detuning for both qubits.

Power-dependent response reveals two sequential dispersive shifts in the cavity transmission, with threshold powers and shift directions distinguishable for each qubit. The first shift is consistently attributed to the fixed-frequency qubit (smaller pads, lower Ic), while the second shift—and accompanying flux dependence—unambiguously results from the SQUID-based qubit. The two-stage behavior confirms simultaneous coupling of two independently addressable graphene JJs to a single 3D cavity mode.

Figure 6: Two-qubit device loaded in 6 GHz and 6.8 GHz cavities. Power-dependent response and flux modulation show two distinct dispersive regimes across four cooldowns.

Quantitative extraction of dispersive shifts and corresponding coupling strengths, for both types of qubits, demonstrates that coupling parameters are robust to repeated thermal cycling. Critical photon number analysis and onset power variances further corroborate the assignment of each shift to its respective circuit, consistent with expected transmon anharmonicity and drive-induced saturation.

Numerical HFSS simulations provide coupling and capacitance estimates (g/2π∼78.9 MHz; C∼32.9 fF) for the single-JJ transmon, matched to observed device behavior.

Figure 7: Simulation of eigenmodes and avoided crossing for the coupled qubit-cavity system, with geometric layout yielding the expected coupling constant.

Decoherence Mechanisms and Coherence Times

Direct relaxation (T1) and linewidth-based dephasing (T2∗) measurements conclusively indicate that, despite integration of 2D materials with well-controlled fabrication, coherence metrics remain well below state-of-art for conventional aluminum-based 3D transmons. Lower bounds for T2∗ reside in the 5–20 ns range, with T1≤48 ns. The dephasing is clearly dominated by strong flux noise and device-to-device variations, likely inheriting contributions from graphene junction quality and processing residues, echoing observations in other 2D material-based superconducting qubits.

Figure 8: Direct measurement of relaxation and dephasing in the single-qubit device.

Implications and Outlook

The study establishes (i) robust coupling of 2D-material weak-link superconducting circuits to 3D microwave cavities and (ii) operation of simple two-qubit architectures with spatially separated, independently controlled JJs, all within the cQED paradigm. Multiqubit readout is achieved using a shared mode, and coupling can be flexibly tuned by geometric and spectral means unavailable in planar cQED. These advances provide a crucial platform for extended studies of noise mechanisms, junction optimization, and integrated quantum logic using van der Waals heterostructures.

For practical advancement, significant improvements are required in the suppression of low-frequency noise and decay mechanisms intrinsic to encapsulated graphene JJs. Further material development, surface processing, and improved shielding are necessary to realize coherence times competitive with conventional Al-based devices. The demonstrated flexibility of the 3D architecture, however, ensures this platform’s suitability for testing new device recipes, scaling to larger multiqubit systems, and hybrid integration with other quantum circuit components.

Conclusion

This work successfully demonstrates the architecture, measurement, and analysis of single and two-qubit graphene-based superconducting quantum circuits strongly and dispersively coupled to 3D copper cavities. Experimental access to multiple coupling regimes through cavity frequency reconfiguration has been exploited to elucidate coupling physics, noise sensitivity, and device limitations. The results highlight the central challenges in coherence for 2D material-based transmon devices, while validating the architecture as a valuable testbed for advancing hybrid quantum technologies, multiqubit integration, and noise studies in superconducting circuits based on van der Waals heterostructures (2512.21213).