TokSuite: Measuring the Impact of Tokenizer Choice on Language Model Behavior (2512.20757v1)

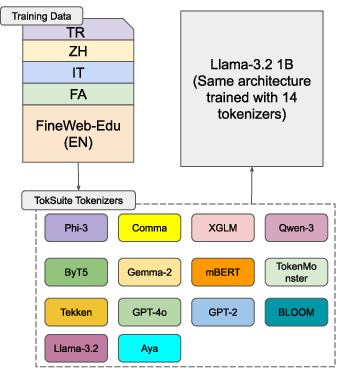

Abstract: Tokenizers provide the fundamental basis through which text is represented and processed by LMs. Despite the importance of tokenization, its role in LM performance and behavior is poorly understood due to the challenge of measuring the impact of tokenization in isolation. To address this need, we present TokSuite, a collection of models and a benchmark that supports research into tokenization's influence on LMs. Specifically, we train fourteen models that use different tokenizers but are otherwise identical using the same architecture, dataset, training budget, and initialization. Additionally, we curate and release a new benchmark that specifically measures model performance subject to real-world perturbations that are likely to influence tokenization. Together, TokSuite allows robust decoupling of the influence of a model's tokenizer, supporting a series of novel findings that elucidate the respective benefits and shortcomings of a wide range of popular tokenizers.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper looks at a simple but powerful idea: LLMs don’t read text exactly as humans do. Before a model sees your words, the text is chopped into small pieces called “tokens” by a tool called a tokenizer. The authors ask: how much does the choice of tokenizer change what a LLM can do?

To find out, they built a set of 14 LLMs that are identical in every way except for the tokenizer. Then they tested them on a new benchmark that includes clean text and real-world “messy” text (like typos, different scripts, emojis, and math formatting) across five languages: English, Turkish, Italian, Farsi, and Chinese.

Key Questions

The paper focuses on three easy-to-understand questions:

- If you keep the model and training data the same, but swap the tokenizer, does performance change?

- Which tokenizers handle real-world text best (typos, different alphabets, emojis, and formatting)?

- Do bigger vocabularies or larger models automatically fix tokenizer problems?

How They Studied It

Think of tokenizers like different ways to cut a cake:

- Some cut by letters or bytes (very small pieces) — like ByT5.

- Some cut by subwords (chunks of words that appear often) — like BPE, WordPiece, or Unigram.

- Some use special strategies — like TokenMonster, which “looks ahead” before deciding how to cut.

Here’s their approach, explained in everyday terms:

- They trained 14 mini LLMs that are clones except for the tokenizer. Same architecture, same training settings, same multilingual data.

- They made a shared “super list” of token pieces so that common pieces start from the same initial state across models. This helps compare tokenizers fairly.

- They built a benchmark of simple multiple-choice questions that most models can answer when the text is clean. Then they created versions with realistic changes:

- Typing with the “wrong” keyboard (like Turkish typed on an English keyboard)

- Optional marks in Farsi, traditional vs. simplified Chinese, and romanized text like Pinyin or “Finglish”

- Typos, missing spaces, or look-alike characters (Unicode “homoglyphs,” such as the Latin “a” vs. the Cyrillic “a” that looks the same)

- Emojis, style changes, and special formatting

- Math and STEM content, including LaTeX formulas and diagrams

- They measured how much accuracy drops when the text is perturbed, compared to each model’s accuracy on the clean version. Smaller drops mean a more robust tokenizer.

Main Findings

Here are the big takeaways, in simple terms:

- Tokenizer choice really matters. Because the models were identical except for the tokenizer, differences in performance come from tokenization itself.

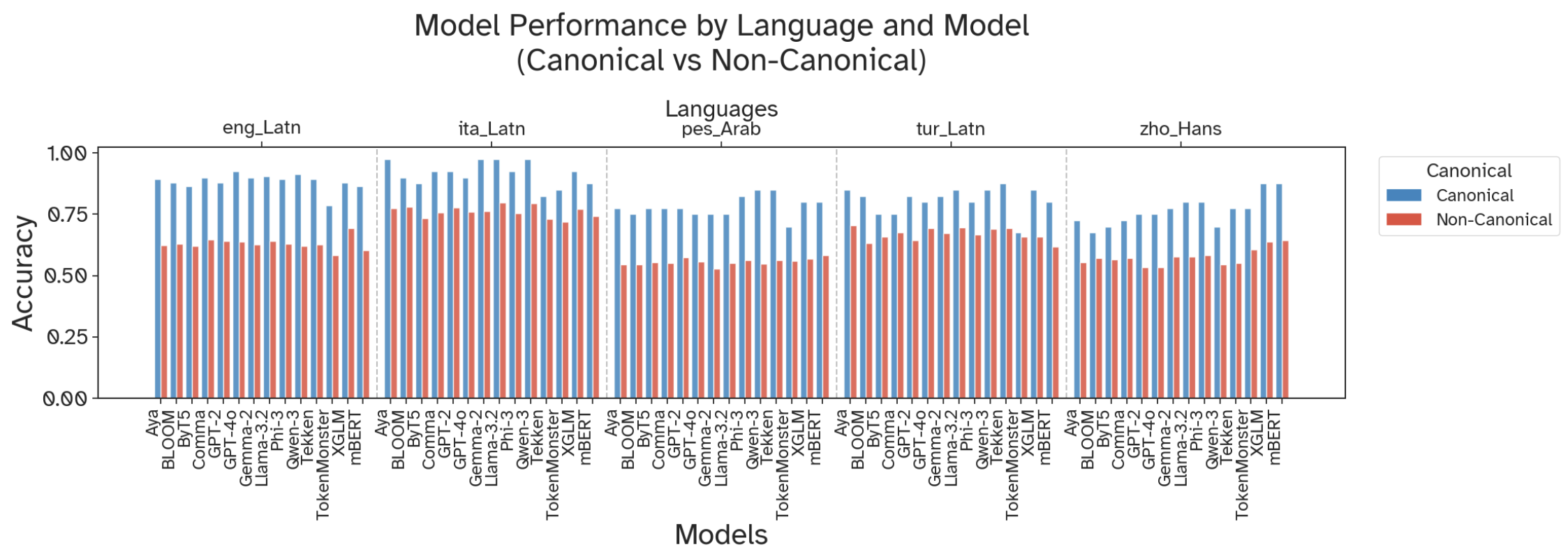

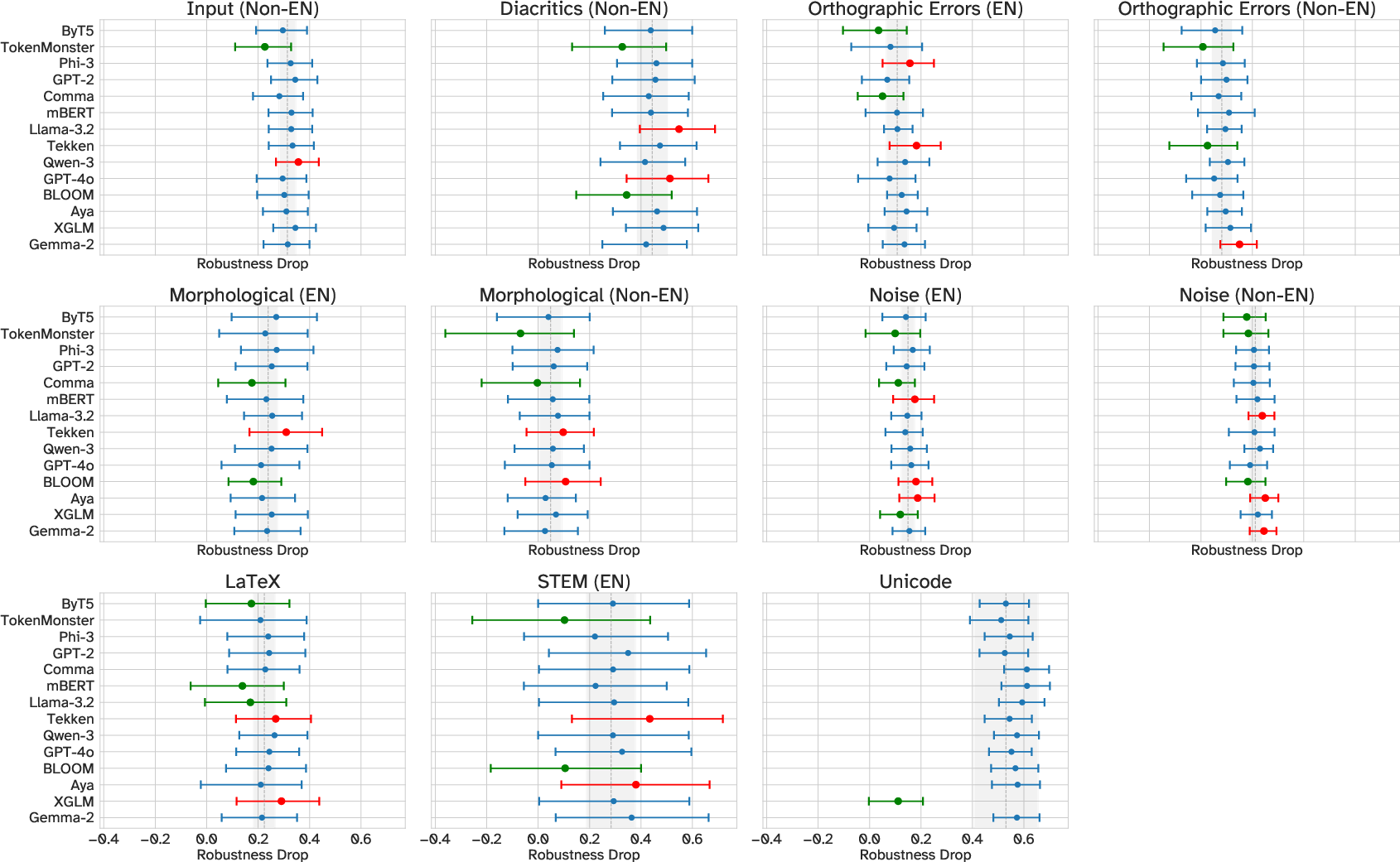

- Real-world text is harder in non-English languages. All tokenizers struggled more when the text was “messy” in Turkish, Italian, Farsi, or Chinese than in English.

- Byte-level and “ungreedy” tokenizers were surprisingly tough:

- ByT5, which reads text byte-by-byte (very small pieces), handled typos and weird characters well. It doesn’t break apart when it sees something unusual.

- TokenMonster, with a special “look ahead” strategy, was very robust even with a smaller, English-only vocabulary. It often beat much larger multilingual tokenizers.

- Unicode styling (special characters that change how text looks) breaks most models. Formatting tricks caused the biggest performance drops. One tokenizer (XGLM) neutralized a lot of styling by normalizing characters, which helps with styled text but can hurt in technical areas where exact formatting matters.

- Math and STEM formatting caused extra trouble. Even simple formulas or scientific notation can fail if the tokenizer strips or changes important structure like spaces, symbols, or subscripts.

- Bigger isn’t always better. Making the model larger or training it longer improved clean-text scores, but only slightly reduced robustness problems. Tokenizer design mattered more than scale.

Why It Matters

- Better everyday performance: People make typos, use emojis, switch keyboards, and mix scripts. Robust tokenizers help models understand you anyway.

- Fairness across languages: The right tokenizer reduces the gap between English and other languages, making AI more inclusive.

- Technical reliability: STEM and coding depend on exact characters and spacing. Tokenizers that preserve structure help models perform better on math and scientific tasks.

- Smarter model design: Instead of just making models bigger, choosing or inventing better tokenizers can yield stronger, more reliable systems.

In short, the paper shows that tokenizers aren’t a minor detail—they’re a core part of how LLMs think. Picking the right tokenizer can make models more robust, multilingual-friendly, and better at handling the messy reality of human text.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of concrete gaps and unresolved questions that future work could address:

- Attribution ambiguity across tokenizer design factors: Off-the-shelf tokenizers differ simultaneously in algorithm, normalization, pre-tokenization, OOV policy, digit/whitespace rules, and training corpora; controlled ablations that retrain each tokenizer family on the same corpus with toggled features are needed to isolate causal factors (e.g., algorithm vs normalization vs byte-fallback).

- Fixed-token training budget confound: Equal token budgets gave unequal byte/document exposure and unequal effective context per update across tokenizers; test alternative controls (fixed-byte, fixed-character, fixed-word budgets) and report how conclusions change.

- Context-window comparability: A 4k-token context encodes vastly different amounts of text across tokenizers; quantify the impact on long-range tasks and evaluate fairness under fixed-byte/character contexts.

- Compute-cost and optimization parity: Vocab size changes softmax cost and embedding parameters; report and compare training/inference FLOPs, wall-clock, memory, and convergence across tokenizers; explore whether per-tokenizer hyperparameter tuning (LR, batch size, clipping) alters robustness rankings.

- Super-vocabulary initialization effects: Shared initialization for overlapping tokens may advantage some tokenizers; ablate with independent initialization and alternative mapping policies (especially for boundary-marked tokens like “##”, “▁”).

- Scale and architecture generalization: Results are shown mainly for ~1B (and a small 7B check) decoder-only LLaMA-like models; test whether findings persist for larger models, MoE, encoder–decoder architectures, and with longer training schedules.

- Post-pretraining pipeline effects: Assess how instruction tuning, SFT, RLHF, and safety finetuning modify tokenizer-driven robustness differences.

- Domain coverage gaps: Code, biomedical, legal, highly structured/tabular text, and markup-heavy domains were largely excluded; evaluate tokenizer effects where whitespace, punctuation, and formatting carry semantics (e.g., code, chemistry, math proofs).

- Language/script coverage limits: Only EN, TR, IT, FA, ZH were included; extend to low-resource and orthographically diverse scripts (e.g., Devanagari, Thai, Khmer, Korean, Japanese with Kana/Kanji mix, Hebrew, extended Cyrillic), and dialectal variation beyond the few covered.

- Code-switching and mixed-script inputs: Systematically evaluate sentences mixing scripts/languages (e.g., Hinglish, Arabizi with emoji), beyond simple romanization cases.

- Richer Unicode phenomena: Go beyond homoglyphs and styling to include zero-width joiners/non-joiners, complex emoji ZWJ sequences, regional flags, and directionality controls in RTL scripts; quantify tokenizer-specific failure modes.

- Task-form coverage: Current evaluation is multiple-choice completion; test free-form generation, chain-of-thought, summarization, translation, retrieval, and structured output tasks where tokenization granularity may alter decoding behavior and planning.

- Robustness metric sensitivity: Results depend on byte-normalized log-likelihood and relative accuracy drop; verify ranking stability under alternative normalizations (per-character, per-word, per-token) and robustness measures (e.g., adversarial accuracy, calibration under shift).

- STEM/LaTeX normalization trade-offs: Design and evaluate content-aware normalization that mitigates styling noise without destroying essential structural notation (LaTeX, units, formulas); compare NFKC/NFKD, custom pipelines, and tokenizer-integrated normalization.

- Data augmentation for robustness: Test whether training-time perturbation augmentation (diacritics variants, homoglyphs, OCR noise, romanization, spacing variants) reduces fragility independent of tokenizer design.

- Hybrid/dynamic tokenization: Explore designs that combine byte-level fallback with adaptive subword segmentation or “ungreedy” lookahead; characterize the robustness–efficiency Pareto frontier at scale.

- Byte-level robustness vs efficiency: Quantify end-to-end compute/training-time overhead needed for byte-level tokenizers to match subword performance; provide compute-normalized robustness curves across model sizes.

- OOV handling ablations: Within a fixed algorithm, toggle byte-fallback vs UNK and measure impacts on multilingual noise robustness and efficiency.

- Numerals and whitespace policies: Isolate effects of thousand-grouping vs digit-per-token and whitespace collapsing/preservation on math/STEM, dates, and code; identify best practices.

- Morphology-aware tokenization: Diagnose per-language failures tied to agglutination/inflection; test morpheme-aware segmentation and cross-boundary merge algorithms (e.g., Boundless BPE, SuperBPE) on robustness and efficiency.

- Adversarial tokenization attacks: Beyond organic perturbations, evaluate resistance to constructed attacks (trap words, segmentation-based jailbreaks, style-preserving adversaries) and whether certain tokenizer properties inherently mitigate them.

- Safety and content filtering: Study how tokenizer choice affects safety classifier coverage, jailbreak susceptibility, and filter evasion under multilingual and Unicode-perturbed inputs.

- Decoding-strategy interactions: Analyze whether sampling, beam search, repetition/length penalties, and constrained decoding interact with token granularity to amplify or dampen errors under perturbations.

- Training mixture realism: The high share of the four non-English languages may understate cross-lingual interference typical in massively multilingual settings; vary mixing ratios to quantify interference vs robustness trade-offs.

- Benchmark scale and ecological validity: The ~5k-sample, hand-curated benchmark with simple “canonical” items may not reflect real-world distributions; build larger, programmatically perturbed, and in-the-wild corpora to measure robustness at scale.

- Reproducibility details: Clarify missing/“FIX” items (exact links, tokenizer versions, normalization settings), and publish full training compute/cost to enable precise replication and cost–robustness comparisons.

Glossary

- AdamW: A variant of the Adam optimizer that decouples weight decay from the gradient update to improve regularization. "We use the AdamW~\citep{adamW} with a weight decay of 0.1 and a peak learning rate of 0.001 with cosine annealing and 2000 warm-up steps."

- Agglutinative language: A language type where words are formed by stringing together morphemes, often causing long, complex word forms that affect tokenization. "Turkish is an agglutinative language with six additional letters in its alphabet and rich in grammar that severely impacts word form and tokenization."

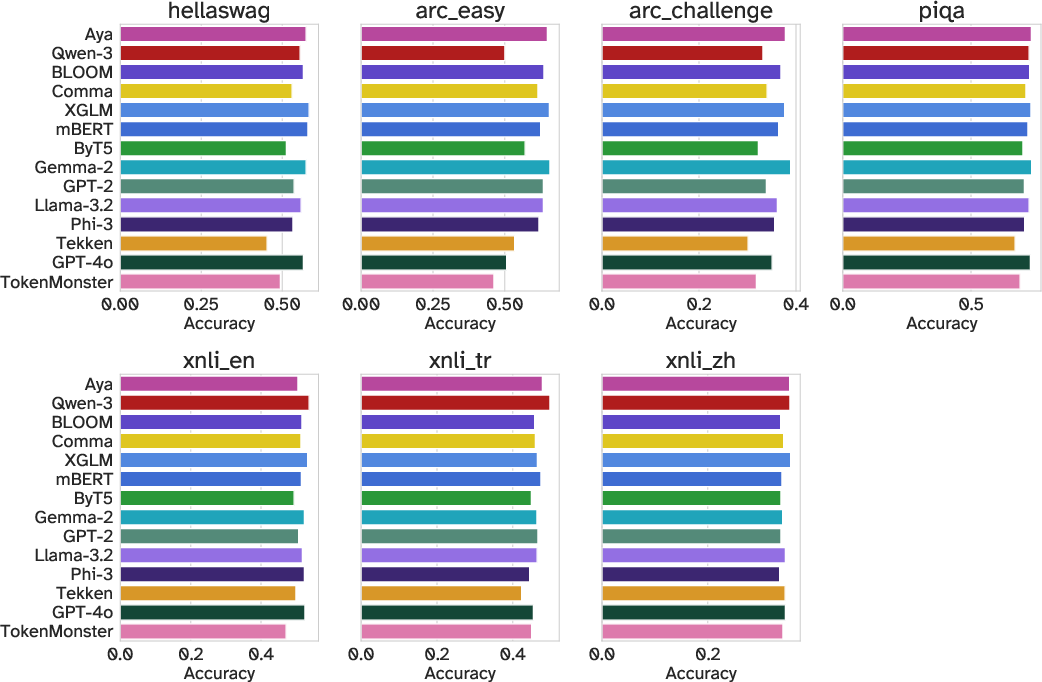

- ARC: A commonsense reasoning benchmark (AI2 Reasoning Challenge) used to evaluate LLMs on standardized science questions. "HellaSwag~\citep{zellers2019hellaswag}, ARC~\citep{clark2018arc}, PIQA~\citep{bisk2020piqa}, and XNLI~\citep{conneau2018XNLI}."

- BPE (Byte-Pair Encoding): A subword tokenization algorithm that iteratively merges frequent symbol pairs to build a vocabulary. "Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE)~\citep{gage1994bpe}, which iteratively merges the most frequent symbol bigrams until reaching vocabulary size ;"

- Bijective mappings: One-to-one correspondences between two sets; here, mappings between tokenizer-specific and unified token spaces to align shared tokens. "we develop a novel vocabulary unification framework that creates bijective mappings between tokenizer-specific and unified token spaces."

- Bootstrap (statistical): A resampling method used to estimate statistics (e.g., mean drops) by repeatedly sampling with replacement. "We report the mean drop derived from a 10,000-trial bootstrap in \cref{tab:multilingual_tokenization_robustness}."

- Byte-fallback: A design that ensures all 256 byte values are in the vocabulary so any Unicode character can be tokenized. "“byte-fallback” forces to include the 256 bytes needed to represent any character in Unicode."

- Byte-level tokenization: Tokenization at the byte (character) level using a fixed Unicode-based vocabulary rather than learned subwords. "Our suite of models covers a wide range of tokenizer types, selected among popular pretrained tokenizers as representatives of their main distinctive features, from byte-level tokenization to subword-based approaches..."

- Byte-length normalized log-likelihood: A likelihood metric normalized by input byte length to fairly compare models across different tokenizations. "We evaluated models with lm-eval's~\citep{eval-harness} byte-length normalized log-likelihood."

- ByT5: A byte-level tokenizer/model that uses predefined Unicode bytes, often more robust to noisy multilingual input. "Byte-level models like ByT5~\citep{xue2022byt5} use predefined Unicode vocabularies rather than learned ones~\citep{mielke2021between}."

- Compression efficiency: How effectively a tokenizer compresses text into fewer tokens, affecting training efficiency and coverage. "each with distinct trade-offs between compression efficiency and linguistic coverage."

- Continuation token markers: Special markers used in subword schemes to indicate that a token continues a word (e.g., prefixes like ##). "continuation token markers for subword boundaries"

- Cosine annealing: A learning rate schedule that decays the rate following a cosine curve, often with restarts. "a peak learning rate of 0.001 with cosine annealing and 2000 warm-up steps."

- Diacritics: Marks added to letters that alter pronunciation or meaning; their optional use affects tokenization consistency. "Diacritics perturbations include presence of optional diacritics, where text remains valid with or without marks..."

- Embedding table: A matrix mapping token IDs to dense vector representations used as model inputs. "These IDs are then used to look up a vector representation of the token in an LM's embedding table..."

- Flores200: A multilingual dataset of parallel sentences used to assess cross-lingual tokenization efficiency. "using 10,000 parallel Flores200~\citep{nllb2022} samples"

- HellaSwag: A commonsense inference benchmark with adversarially filtered scenarios for evaluating LLMs. "HellaSwag~\citep{zellers2019hellaswag}"

- Homoglyphs: Visually similar characters with different Unicode code points that can disrupt tokenization. "homoglyphs---visually similar characters with different Unicode values."

- Inductive bias: Built-in assumptions or constraints in a model design that guide learning and generalization. "tokenizers provide a cost-free inductive bias that fundamentally shapes robustness and efficiency."

- LaTeX: A typesetting system for mathematical and scientific notation, whose formatting can challenge tokenizers. "LaTeX and Formatting variations include straightforward examples such as \verb|$6$| and \verb||..."

- lm-eval: A standardized evaluation harness for LLMs supporting multiple tasks and metrics. "We evaluated models with lm-eval's~\citep{eval-harness} byte-length normalized log-likelihood."

- Log-linear benefit: A relationship where improvements scale proportionally to the logarithm of a variable (e.g., vocabulary size). "indicated a log-linear benefit from scaling the input vocabulary"

- Log-likelihood: The logarithm of the probability assigned by a model to observed data; used as a scoring metric. "byte-length normalized log-likelihood."

- Lossy pre-processing: Input normalization that removes or alters information, harming tasks that rely on precise formatting. "where its “lossy” pre-processing destroys the essential structural and spatial information required for comprehension."

- Lookahead: A tokenization strategy that considers upcoming characters when deciding current token boundaries. "employing an “ungreedy” algorithm that revises tokenization by lookahead."

- mBERT: Multilingual BERT tokenizer/model supporting many languages with WordPiece tokenization. "mBERT~\citep{devlin2019bert}"

- Morphological segmentation: Tokenization that splits words into morphemes, improving handling of rich morphology. "morphological segmentation consistently outperformed BPE across morphologically rich languages"

- Neural Machine Translation (NMT): Sequence-to-sequence machine translation using neural networks. "subword-based NMT"

- NFKC normalization: A Unicode normalization form (Normalization Form KC) that composes/decomposes and compats characters. "thanks to its NFKC normalization during preprocessing."

- OCR (Optical Character Recognition): Technology converting images of text into digital text, often introducing noise. "formatting inconsistencies arising from sources such as OCR or other data processing pipelines."

- Orthographic Perturbations: Variations and errors in spelling, accents, scripts, or stylistic conventions that affect tokenization. "Orthographic Perturbations include input medium challenges, diacritics perturbations, orthographic errors..."

- Out-of-vocabulary (OOV): Tokens not present in the tokenizer’s vocabulary, requiring fallback or unknown token handling. "out-of-vocabulary (OOV) handling"

- Parity (tokenization metric): Cross-lingual fairness measured as the ratio of tokenized lengths for parallel sentences. "Parity: cross-lingual fairness measured as the ratio of tokenized lengths for parallel sentences"

- PCW (Proportion of continued words): The fraction of words that require multiple tokens under a tokenizer. "Proportion of continued words (PCW): fraction of words requiring multiple tokens"

- Perplexity: A measure of how well a probability model predicts a sample; lower values indicate better performance. "achieving lower perplexity"

- Pinyin: The standard romanization for Mandarin Chinese used to represent pronunciation in Latin script. "romanization through Pinyin, the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet, and errors relating to it"

- Pre-tokenization: A preprocessing step that splits text into coarse units (e.g., words) before subword learning/segmentation. "Tokenization pipelines often use some form of pre-tokenization, which segments the input text into “intuitive” tokens..."

- Romanization: Writing text from non-Latin scripts using the Latin alphabet. "romanization---writing text in Latin script like Pinyin for Chinese or Finglish for Farsi."

- SentencePiece: A tokenizer framework (often Unigram) that learns subword units directly from raw text. "SentencePiece~\citep{kudo2018subword}"

- Subword fertility: The average number of tokens per word, indicating how much segmentation occurs. "Subword fertility (SF): mean number of tokens per word"

- Subword-based approaches: Tokenization methods that use pieces of words (subwords) instead of whole words or bytes. "subword-based approaches including BPE, SentencePiece, and WordPiece variants."

- Super vocabulary: A unified vocabulary formed by the union of multiple tokenizers’ vocabularies to align embeddings. "Then, we create a super vocabulary, , by taking the union of all vocabularies ."

- Token budget: A fixed number of tokens allocated for training or evaluation, impacting how much text a model sees. "we use a fixed token budget in line with the current practice in LLM training and reporting."

- TokenMonster: A tokenizer using a global vocabulary and an ungreedy, lookahead-based segmentation algorithm. "TokenMonster~\citep{forsythe2025tokenmonster}"

- Unigram: A subword tokenization algorithm that prunes a candidate vocabulary to minimize unigram language-model loss. "Unigram~\citep{kudo2018subword}, which starts with all possible segmentations and removes symbols causing minimal unigram loss increase."

- Unicode normalization: Standardized transformation of Unicode text (e.g., composing/decomposing characters) before tokenization. "unicode normalization strategies"

- Unicode styling characters: Special Unicode symbols that alter visual presentation without changing semantics, often breaking tokenization. "Unicode styling and character transformations degrade performance consistently across nearly all models"

- Unicode-based formatting: Formatting that uses Unicode constructs (e.g., enclosed characters) to style text. "Structural text elements includes Unicode-based formatting (see \cref{fig:style_nfkc})"

- Ungreedy algorithm: A tokenization strategy that avoids greedy merges and can revise token choices based on future context. "“ungreedy” algorithm"

- Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests: A non-parametric statistical test for comparing paired samples to assess significance. "Paired Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests \citep{wilcoxon} determine statistical significance of performance differences..."

- WordPiece: A subword tokenization algorithm that merges units to maximize the likelihood of the training data. "WordPiece~\citep{wu2016wordpiece}, which merges symbols by maximizing training data likelihood"

- Zero-width characters: Invisible spacing characters that can alter token boundaries without changing visible text. "This category also includes spacing irregularities with zero-width characters."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

- Industry:

- Software Development: The paper highlights the impact of different tokenizers on LMs, suggesting the creation of custom tokenizers tailored for specific industry needs, such as enhancing model performance in domains like coding languages where current models fall short (e.g., T5). This can lead to improved code generation and more efficient debugging tools.

- Machine Translation: Tokenization strategies that incorporate multilingual support can improve machine translation services by reducing errors in translation across languages with different scripts, benefiting companies in global markets.

- Natural Language Processing Tools: Deploy refined tokenizers into existing NLP tools for better handling of OCR errors and orthographic mistakes in various applications like document analysis and chatbots.

- Academia:

- Linguistic Research: The study provides a foundation for developing tokenizers that can better handle morphological and orthographic variations across diverse languages, aiding linguistic studies and the development of educational tools for language learning.

- AI Research: An open-source collection of models differing only in tokenization provides a unique dataset for researchers focusing on model robustness and efficiency, facilitating advancements in AI model architecture.

- Policy:

- Language Policy Development: Insights from tokenizer differences in handling multilingual corpora can inform language preservation policies and encourage the development of technology to support lesser-represented languages in digital spaces.

- Public Sector Multilingual Services: Develop tokenizers that cater to governmental needs for multilingual document processing and translations, improving communication and service delivery in multilingual regions.

- Daily Life:

- Enhanced Text Services: Integrating new tokenizer strategies into personal assistant technologies can improve speech-to-text recognition, especially in noisy environments or among speakers with diverse accents.

- Accessibility: Customized tokenizers can improve text processing tools for individuals with dyslexia or other reading difficulties by providing more accurate text representations.

Long-Term Applications

- Industry:

- Healthcare: Further research into tokenization effects in LMs can enhance models designed for medical text analysis, allowing for better interpretation of diverse medical records and improving AI-assisted diagnostics.

- Robotics: Developing novel tokenizers robust to perturbations and diverse inputs will enhance robotic comprehension systems and improve interactions between humans and robots.

- Academia:

- Cross-discipline Educational Tools: Long-term development of tokens that capture technical noise handling in mathematical and STEM content could lead to advanced educational software tailored to various disciplines.

- Cognitive Computing: Explore tokenization strategies in cognitive computing models to understand human-like processing in AI systems for more natural interactions.

- Policy:

- Global Communication Standards: Further scaling of tokenizer research could contribute to international standards in digital communications, ensuring consistent processing across platforms and languages.

- Environmental Insights: Integrate tokenizers with environmental data models to improve data parsing, potentially influencing policy decisions on climate change and resource management.

- Daily Life:

- Smart Home Systems: Develop tokenizers that adapt to the inconsistent linguistic input inherent in smart home voice commands, leading to systems that can understand and execute commands more accurately.

- Cultural Heritage Preservation: Use enhanced tokenization methodologies to digitize and preserve cultural heritage texts, ensuring accurate representation and archiving.

Assumptions and Dependencies

- Many applications depend on the scalability and adaptability of current LLMs, requiring continued advancements in AI training frameworks.

- Successful deployment in industry and policy often requires collaboration with domain experts to tailor tokenizers to specific needs.

- Long-term applications involve substantial research investments to ensure efficacy and practical deployment in complex tasks.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.