KerJEPA: Kernel Discrepancies for Euclidean Self-Supervised Learning (2512.19605v1)

Abstract: Recent breakthroughs in self-supervised Joint-Embedding Predictive Architectures (JEPAs) have established that regularizing Euclidean representations toward isotropic Gaussian priors yields provable gains in training stability and downstream generalization. We introduce a new, flexible family of KerJEPAs, self-supervised learning algorithms with kernel-based regularizers. One instance of this family corresponds to the recently-introduced LeJEPA Epps-Pulley regularizer which approximates a sliced maximum mean discrepancy (MMD) with a Gaussian prior and Gaussian kernel. By expanding the class of viable kernels and priors and computing the closed-form high-dimensional limit of sliced MMDs, we develop alternative KerJEPAs with a number of favorable properties including improved training stability and design flexibility.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching computers to learn useful information from pictures without needing labels. The authors focus on a popular idea called self-supervised learning (SSL), where a model learns by making different “views” of the same image (like crops or rotations) and trying to make their internal summaries (embeddings) match. The big challenge is to prevent the model from cheating by making all embeddings identical. To avoid this, the paper proposes a new family of methods—called KerJEPA—that use flexible mathematical tools (kernels) to keep the embeddings spread out in a healthy, well-shaped way.

Key Objectives

The paper asks and answers a few simple questions:

- How can we prevent the “collapse” problem (where all embeddings look the same) while still training efficiently?

- Can we go beyond one fixed shape for the embeddings (like a simple bell curve) and design better, more flexible rules that fit different needs?

- How can we connect existing methods to well-known tools in statistics (like kernels and discrepancies) so we can improve stability, speed, and performance?

- What tradeoffs do we face (like calculation time vs. randomness) when scaling up to high-dimensional embeddings?

Methods Explained Simply

Think of each image’s embedding as a point in a big space. We want these points to have a nice, well-behaved shape so the model doesn’t cheat but still learns useful features.

To do this, the paper uses two main ideas:

- Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD): Imagine comparing two crowds by how their “average behavior” looks after passing them through many different filters (kernels). If the learned embeddings and a target shape (like a bell curve) look similar under these filters, we’re doing well.

- Kernel Stein Discrepancy (KSD): Instead of sampling from the target shape, KSD measures how the learned embeddings fit the target’s “rules,” using a clever tool called a score function (it tells you how likely points are near each location in the target). It’s like checking if your points “flow” the way the target shape says they should, which can be very efficient and powerful.

To make high-dimensional comparisons easier, the paper also uses “slicing,” which is like looking at shadows: project points onto random lines (directions), compare the one-dimensional shadows, and average the results. This makes big problems simpler but adds some randomness.

In practical terms, the authors:

- Show that LeJEPA’s original regularizer (based on the Epps–Pulley test) is really just MMD with a specific kernel.

- Derive exact formulas that let you avoid slicing if you’re willing to do more computation, and show when slicing is helpful.

- Propose using different kernels, including “heavy-tailed” ones (like IMQ), which pay more attention to differences far away from the center—often helpful in real data.

- Offer both sliced (fast, more random) and unsliced (exact, more compute) versions of regularizers (MMDReg and KSDReg), so you can pick what fits your setup.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

- Clear connection: They prove that LeJEPA’s regularizer is mathematically equivalent to a kind of MMD, and show how slicing changes the effective kernel and its tail behavior. This helps us understand and improve the method.

- More flexible designs: By allowing different kernels (like Gaussian or IMQ) and different target shapes (priors like Gaussian or Laplace), they give you a toolbox to tailor the geometry of embeddings to your downstream tasks.

- Better stability in training: Using kernel-based regularizers, especially KSD with heavy-tailed kernels, can reduce training noise and improve stability—important in high-dimensional settings.

- Practical performance: In experiments on ImageNette with a ViT-s/8, their best variant (unsliced KSD with an IMQ kernel) slightly outperforms the LeJEPA baseline. The gains aren’t giant, but they are consistent and come with improved design freedom.

- Tradeoffs mapped: They explain when slicing is good (fast, linear time), when unsliced is better (less random, exact but quadratic time), and how high-dimensional limits let you approximate fancy kernels (like Kummer) with simpler ones (like IMQ).

Implications and Impact

This work makes SSL more reliable and customizable. By connecting LeJEPA to MMD and introducing KSD-based methods, it:

- Helps prevent collapse with mathematically solid, flexible rules.

- Gives practitioners multiple options (fast sliced vs. exact unsliced, different kernels and priors) to match their compute budget and task needs.

- Improves stability for large embeddings, which matters for modern vision models.

- Encourages thinking carefully about the “shape” of learned features, so they transfer better to real tasks.

In short, KerJEPA turns a successful idea into a broader, more powerful framework, making self-supervised learning both steadier and smarter.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, consolidated list of the paper’s key knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that remain unresolved. Each item is phrased to be concrete and actionable for follow‑up work.

- Lack of large‑scale validation: results are limited to ImageNette with a single ViT‑s/8 configuration; no evaluation on standard SSL benchmarks (e.g., ImageNet‑1k), diverse backbones, or downstream tasks beyond classification (e.g., detection, segmentation, retrieval).

- Limited exploration of priors: while the framework allows non‑Gaussian priors (Laplace, Student‑t), experiments focus mainly on Gaussian/Laplace; there is no systematic study of how different priors affect representation geometry and downstream performance across tasks.

- Bandwidth selection is under‑specified: kernel bandwidth γ is grid‑searched but lacks principled, data‑dependent selection strategies; no analysis of sensitivity or adaptive schedules (e.g., annealing, median heuristic, cross‑validation) and their impact on stability/performance.

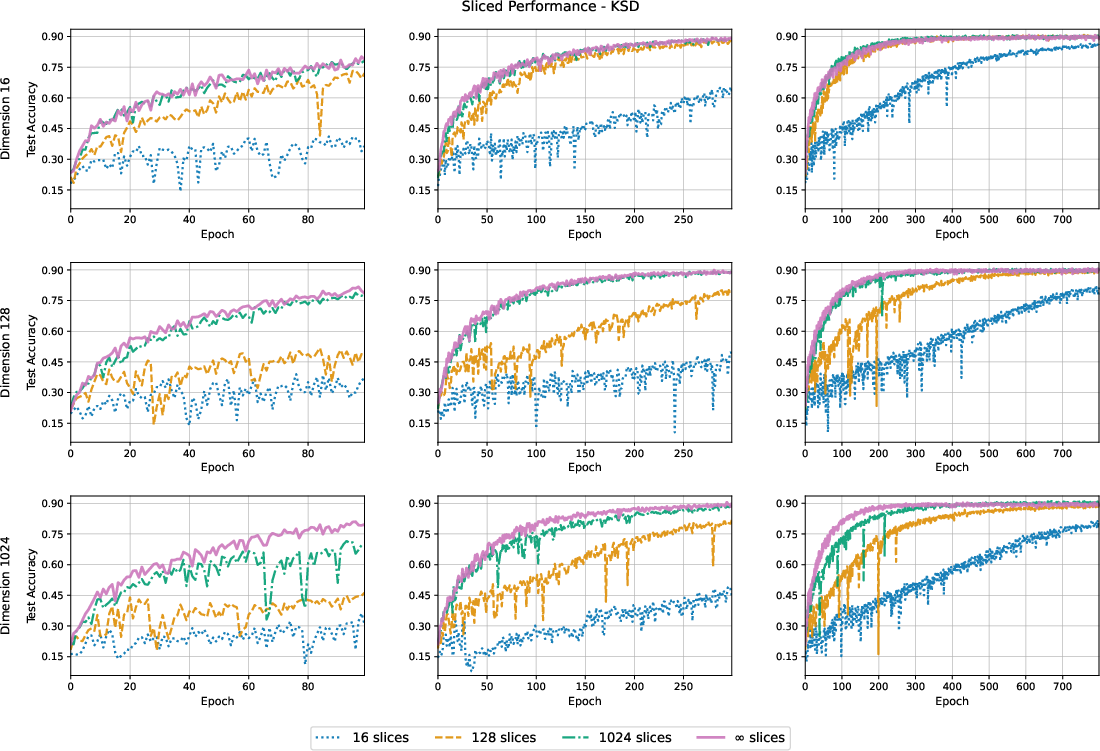

- No quantitative study of slicing variance: training stability claims are not backed by formal or empirical analysis relating gradient variance to embedding dimension d, number of slices m, and number of quadrature knots u; missing ablations for m and u across d and batch size n.

- Quadrature error is uncharacterized: Gauss‑Hermite integration with 21 knots is used without error bounds; no guidelines on knot count vs kernel bandwidth and σ, or adaptive quadrature to control integration bias during training.

- Missing wall‑clock and memory benchmarks: sliced vs unsliced approaches are compared conceptually, but there are no measurements of compute, memory, throughput, and scaling on modern GPUs/TPUs to inform practical trade‑offs.

- Unclear geometry of learned representations: heavy‑tailed kernels induced by slicing (via Kummer) are hypothesized to have favorable properties, but there is no empirical analysis of representation statistics (norm distributions, covariance spectra, isotropy), nor links to downstream task gains.

- Approximation of Kummer by IMQ lacks finite‑d guarantees: the paper cites asymptotic equivalence for d ≥ 20, but provides no error bounds, calibration procedures, or diagnostics for moderate d typical in practice (e.g., 64–1024).

- Positive definiteness and characteristic properties of the induced Kummer kernel are not fully established: there is no proof or empirical verification that the Kummer kernel is PD and characteristic across bandwidths and dimensions used in training.

- KSD conditions and test power in SSL are not connected to downstream utility: claims that KSD (especially IMQ) has greater test power are not linked to representation learning outcomes; need controlled studies connecting discrepancy test power to accuracy, calibration, and robustness.

- Score functions for non‑Gaussian priors are not stress‑tested: Laplace score s(x) = −normalize(x)/σ is ill‑defined at x = 0; no discussion of numerical stabilization (e.g., ε‑smoothing), behavior near the origin, or regularization to prevent exploding gradients.

- No analysis of the guillotine mismatch: the paper highlights that training acts on projector outputs while transfer uses backbone features, but provides no experiments quantifying how regularization choices propagate to backbone representations or reduce this mismatch.

- Absence of collapse diagnostics: while the regularizers are intended to prevent representation collapse, there are no metrics tracked (e.g., per‑dimension variance, covariance condition numbers, entropy) to verify collapse avoidance across training regimes.

- Limited ablations on augmentations: augmentation pipeline is fixed; no exploration of how discrepancy regularizers interact with stronger/weaker augmentation regimes, multicrop, or domain‑specific augmentations.

- Hyperparameter robustness and reproducibility: reported gains (e.g., IMQ‑KSD reaching ~91.9%) are within 1% of baselines and accompanied by single standard errors; there are no multi‑seed runs, confidence intervals over training runs, or sensitivity plots to ensure robustness.

- No adaptive prior or σ selection: σ is fixed; there is no investigation of data‑dependent σ (e.g., matching empirical variance), joint learning of σ with the encoder, or task‑dependent priors that reflect downstream objective regularization (beyond ℓ2/ridge).

- Missing comparisons with random‑feature approximations: spectral forms are proposed (for MMD and KSD), but random Fourier/Stain features are not implemented or benchmarked to reduce the O(n²) cost of unsliced methods.

- No analysis of mini‑batch scaling: the trade‑off discussion mentions batch size n and embedding dimension d, but there is no empirical scaling study of training dynamics, convergence rates, or variance across n, d, and regularization strength λ.

- Interaction with optimizers and weight decay is not studied: theoretical motivation for Gaussian priors under ℓ2 weight decay is cited, but the empirical interplay of optimizer choice (AdamW vs SGD), weight decay values, and regularizer settings is not explored.

- Unclear behavior in extremely high dimensions: while slicing variance grows with d, the paper does not demonstrate training dynamics or estimator performance for large projector sizes (e.g., d ≥ 1024), where slicing is purportedly costly.

- Alternative alignment objectives are not tested: only MSE alignment is used; it remains unknown how discrepancy regularizers interact with contrastive losses, cosine similarity, or predictor architectures (e.g., BYOL‑style).

- Multi‑modal and non‑visual domains are unaddressed: given the general kernel framework, there is no exploration of audio, text, or cross‑modal SSL where priors/kernels might better match domain geometries.

- Direction sampling schemes are not varied: sliced methods rely on random directions uniformly sampled on the sphere; there is no evaluation of deterministic spherical quadratures, low‑discrepancy sequences, or learned directions to reduce variance.

- No calibration or robustness metrics: downstream evaluation focuses solely on top‑1 accuracy; robustness to corruptions, out‑of‑distribution generalization, and calibration are not assessed—key for heavy‑tailed priors/kernels.

- Theoretical generalization beyond ℓ2‑regularized tasks is not formalized: the paper motivates priors for tasks beyond ridge, but lacks formal results on optimal priors/kernels under alternative downstream regularization (e.g., ℓ1, elastic net, margin‑based).

- Missing end‑to‑end guidelines: although trade‑offs are discussed qualitatively, there are no concrete recipes (decision trees, rules of thumb) for choosing kernel/prior, sliced vs unsliced, m/u/γ/σ, as a function of d, n, compute budget, and target tasks.

- Numerical stability and implementation details are incomplete: Kummer‑based estimators and SKSD analytic forms are derived, but there is no implementation report on numerical conditioning, special‑function evaluation accuracy, or fallback approximations when libraries are unavailable.

Glossary

- Baringhaus-Henze-Epps-Pulley (BHEP) test: A multivariate normality test that generalizes the Epps-Pulley test to higher dimensions. "which is equivalent to the multivariate extension called the Baringhaus-Henze-Epps-Pulley (BHEP) test \cite{Baringhaus1988}."

- Bochner's Theorem: A result characterizing shift-invariant positive definite kernels via their Fourier (spectral) measures. "by Bochner's Theorem \cite{bochner}, admits a Fourier representation on non-negative Borel measures with a spectral density defined as"

- Characteristic function (CF): The Fourier transform of a probability distribution, used to uniquely characterize it. "where is the Characteristic Function (CF) for both $\prob{P}$ and $\prob{Q}$"

- Characteristic kernel: A kernel for which the kernel mean embedding is injective, ensuring distinct distributions map to distinct RKHS elements. "If the kernel is characteristic, this mapping is injective"

- Cram-Wold theorem: A theorem stating that equality in distribution of multivariate random variables is equivalent to equality of all one-dimensional projections. "Explicitly, such approaches leverage the celebrated Cram-Wold theorem, stated below."

- Epps-Pulley (EP) test: A goodness-of-fit test for normality based on differences of characteristic functions under a weighting. "LeJEPA selects the Epps-Pulley (EP) \cite{ep-test} test as the isotropic Gaussian regularizer of choice."

- Gauss-Hermite quadrature: A numerical integration technique tailored to Gaussian-weighted integrals. "Integration is done as Gauss-Hermite quadrature approximation."

- Gaussian kernel: The radial basis function kernel used in many kernel methods. "An instance of this shift-invariant kernel is the Gaussian Kernel,"

- Guillotine regularization: A training practice that discards the projector head after pretraining, using only backbone features for downstream tasks. "guillotine regularization: discarding the non-linear projection head after pretraining and utilizing only the backbone features for downstream tasks \cite{guillotine}."

- Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC): A kernel-based measure of statistical dependence between random variables. "Similarly, kernel-based methods have been applied via Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion \cite{hsic-ssl}."

- Inverse Multiquadric (IMQ) kernel: A heavy-tailed kernel of the form that can improve testing power. "it has been shown that the KSD with an IMQ kernel offers even greater statistical testing power than its Gaussian counterpart"

- Integral Probability Metric (IPM): A class of distances between distributions defined via supremum over a function class, including Wasserstein and MMD. "Integral Probability Metrics (IPMs) have analytical properties for reasoning about the similarity of complex probability distributions"

- Isotropic Gaussian prior: A multivariate Gaussian with identical variance in all directions, used as a target distribution for embeddings. "regularizing Euclidean representations toward isotropic Gaussian priors yields provable gains in training stability and downstream generalization."

- Joint-Embedding Predictive Architectures (JEPAs): Self-supervised models that learn by predicting joint embeddings of related views. "Recent breakthroughs in self-supervised Joint-Embedding Predictive Architectures (JEPAs) have established"

- Kernel mean embedding: The mapping of a distribution into an RKHS via the expected kernel feature map. "its kernel mean embedding is defined as"

- Kernel Stein Discrepancy (KSD): A discrepancy that measures how a distribution differs from a target using the target’s score and a kernel. "The Kernel Stein Discrepancy (KSD) \cite{kernel-gof, ksd, sample-quality-kernels, ksdd} eliminates the need for the normalization constant entirely."

- Kummer confluent hypergeometric function: A special function appearing in closed-form expressions for sliced kernel metrics. "where $\kummer$ is the Kummer Confluent Hypergeometric function,"

- Langevin Stein operator: The operator used in Stein’s method to define discrepancies like KSD. "By leveraging the Langevin Stein operator \cite{measuring-stein},"

- Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD): An RKHS-based distance between distributions computed via kernel expectations. "The Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) is an RKHS distance measure between probability distributions $\prob{P}$ and $\prob{Q}$"

- Monte Carlo slicing: Estimating sliced divergences by averaging over random projection directions. "this Monte-Carlo sliced distance estimator has sample complexity bounded"

- Optimal transport: A framework for comparing distributions by transporting mass, leading to metrics like Wasserstein. "More sophisticated distribution matching has been approached through optimal transport, specifically using the Spherical Sliced Wasserstein (SSW) distance \cite{spheresliced}"

- Quadrature: Numerical approximation of integrals via weighted sums at chosen nodes. "the integral \eqref{eq:eps-pulley-test} (cf. \eqref{eq:ep}) is approximated via quadrature"

- Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space (RKHS): A Hilbert space of functions where evaluation is given by an inner product with a kernel representer. "embedding them into a Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space (RKHS) \cite{rkhs}."

- Score function: The gradient of the log-density, , used in Stein methods. "depends only on the score function $s_{\targetprob}(x) = \nabla_x \log \targetprob(x)$ of the target"

- Sliced Integral Probability Metrics (SIPMs): IPMs computed by averaging the base metric over one-dimensional projections. "we adopt Sliced Integral Probability Metrics (SIPMs) and mimic the structure of LeJEPA."

- Sliced Kernel Stein Discrepancy (SKSD): The sliced analogue of KSD, averaging Stein discrepancies over projected marginals. "We now derive the closed-form estimator for the Sliced Kernel Stein Discrepancy (SKSD) using the analytic Cram-Wold approximation."

- Sliced maximum mean discrepancy (MMD): An MMD computed or approximated via integrals over one-dimensional projections. "approximates a sliced maximum mean discrepancy (MMD) with a Gaussian prior and Gaussian kernel."

- Sliced Wasserstein distance: The average of 1D Wasserstein distances over random directions to compare high-dimensional distributions. "motivated the concept of sliced Wasserstein distances \cite{rabin2012wasserstein,bonneel2015sliced}"

- Spectral density: The Fourier-domain weighting function associated with a shift-invariant kernel. "with a spectral density defined as"

- Spherical Sliced Wasserstein (SSW) distance: A sliced Wasserstein metric specialized to spherical geometry for embeddings. "specifically using the Spherical Sliced Wasserstein (SSW) distance \cite{spheresliced}"

- Stein kernel: The kernel obtained by applying the Stein operator to both arguments of a base kernel. "where the Stein kernel is defined by applying the Stein operator to both arguments of a base kernel :"

- Stein's identity: The property that the expectation of the Stein operator under the target distribution is zero. "vanish due to Stein's identity, leaving a measure that depends solely on the interaction of samples"

- Student-t prior: A heavy-tailed target distribution used for regularization in place of Gaussian. "Gaussian, Laplace, and Student-t priors"

- U-estimator: An unbiased estimator built from pairwise terms without self-interactions. "an unbiased U-estimator $\approximate{\fnfont{SKSD}$ of $\fnfont{SKSD}$ may be readily derived"

- V-estimator: A (potentially biased) estimator using averages of functions of samples, including diagonal terms. "One can readily construct a -estimator based on the expressions of the squared KSD"

- Weak convergence: Convergence in distribution of random variables or measures. "for specific classes of kernels, and dimension, KSD metrizes weak convergence."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now by integrating KerJEPA’s kernel-discrepancy regularizers (MMDReg and KSDReg) and the paper’s analytic insights into existing self-supervised learning pipelines and tooling.

- Sector: Software/AI Infrastructure Use case: Plug-and-play regularizers for Euclidean SSL Application: Replace or augment LeJEPA’s SIGReg with KerJEPA’s sliced MMDReg or sliced/unsliced KSDReg modules in PyTorch/JAX training loops to improve training stability, tailor representation geometry, and reduce representation collapse. Tools/workflows: Drop-in loss modules using Gaussian/IMQ kernels, Gauss-Hermite quadrature, random features for KSD; bandwidth and prior selection templates. Assumptions/dependencies: Access to unlabeled data; correct score function for chosen prior in KSD; careful kernel bandwidth selection; compute budget to choose sliced (linear in n) vs unsliced (quadratic in n) variants.

- Sector: Computer Vision for Industry (Manufacturing/Quality Control) Use case: Enhanced defect and anomaly detection Application: Train vision encoders with IMQ-based KSD regularization to improve sensitivity to tail deviations in embeddings, leading to better detection of rare defects without labeled data. Tools/workflows: On-line SSL pretraining with heavy-tailed kernels, instance normalization probes for monitoring; anomaly scoring from embedding distributions. Assumptions/dependencies: Choice of prior that reflects expected embedding geometry (e.g., Gaussian vs Student-t); robust augmentations aligned with imaging conditions; sufficient batch sizes.

- Sector: Healthcare (Medical Imaging) Use case: Label-efficient pretraining for radiology and pathology Application: Pretrain encoders on unlabeled scans using KerJEPA with Laplace or Student-t priors to match heavy-tailed characteristics and improve robustness to atypical findings. Tools/workflows: Sliced MMDReg/KSDReg with analytic spectral forms; clinical data augmentation catalog; linear probes for task-specific evaluation. Assumptions/dependencies: Data governance/privacy constraints; verifying prior/score function correctness; domain-specific augmentation design to avoid spurious invariances.

- Sector: Finance (Risk/Compliance) Use case: Representation learning for heavy-tailed signals Application: Use IMQ-KSD or Laplace-prior MMDReg for embeddings of market or transaction data where tails matter; improves outlier and regime-shift sensitivity for downstream risk models. Tools/workflows: Unlabeled time-windowed image/sequence encoders; tail-aware regularization; monitoring via KSD/MMD-based drift tests. Assumptions/dependencies: Adapting priors and kernels to non-visual modalities; stable data preprocessing; careful hyperparameter selection for bandwidth and regularization weight.

- Sector: Robotics (On-device Perception) Use case: Stable on-device SSL with constrained compute Application: Adopt sliced spectral approximations (finite slices/knots) to keep training linear in batch size while maintaining stable geometry; reduce gradient variance with quadrature tuning. Tools/workflows: Lightweight sliced MMDReg/KSDReg implementations; periodic re-slicing per minibatch; small ViT/Conv backbones with projector heads. Assumptions/dependencies: Tradeoff between slice count and variance; quadrature accuracy; memory limits constrain unsliced (quadratic) methods.

- Sector: Consumer Apps (Photo/Video Search and Organization) Use case: Better embeddings from unlabeled media Application: Deploy KerJEPA-regularized encoders to boost retrieval, clustering, and deduplication quality without labels; robustness to diverse user content. Tools/workflows: Batch pretraining with sliced MMDReg; downstream index-building with Euclidean embeddings; drift detection with MMD/KSD tests. Assumptions/dependencies: Prior and kernel choices tuned to dataset heterogeneity; scalable quadrature/slice settings.

- Sector: Academia (Research & Teaching) Use case: Geometry-aware SSL research and reproducible baselines Application: Use the spectral and high-dimensional limit derivations to study kernel/prior effects, establish theory-practice links (e.g., SIGReg ≡ MMD with Kummer kernel; IMQ approximation for large d). Tools/workflows: Benchmark suites comparing sliced vs unsliced, Gaussian vs IMQ kernels, Gaussian vs Laplace/Student-t priors; ablation scripts for bandwidth/regularization grids. Assumptions/dependencies: Familiarity with RKHS/IPMs/Stein methods; consistent augmentation pipelines; clear reporting of slice/knots and compute tradeoffs.

- Sector: MLOps/Model Quality Use case: Embedding distribution audits and drift testing Application: Replace BHEP/MMD-only tests with KSD-based normality tests (higher power in practice) for monitoring SSL embedding distributions during training and deployment. Tools/workflows: Periodic KSD/MMD evaluation against target priors; alerts for geometry drift; integration with training dashboards. Assumptions/dependencies: Known score for target prior; bounded kernels or random-feature approximations for scalability; appropriate thresholds calibrated on validation runs.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, and development to fully realize KerJEPA’s potential across modalities, systems, and policy frameworks.

- Sector: Foundation Models (Multimodal) Use case: Geometry-aware pretraining beyond vision Application: Extend KerJEPA to audio, text, and multimodal signals with modality-appropriate priors and kernels; align representation geometry with downstream tasks (classification, regression, retrieval) beyond L2-regularized settings. Tools/products: Libraries for cross-modal score functions and spectral forms; AutoML recipes for kernel/prior selection. Assumptions/dependencies: Deriving/approximating priors and scores for non-visual data; robust random-feature approximations for KSD across modalities; empirical validation at scale.

- Sector: AutoML/Meta-learning Use case: Automated geometry selection Application: Meta-learn kernel type, bandwidth, and prior to match downstream objectives and data regimes; dynamically switch between sliced and unsliced regimes based on compute and variance. Tools/products: Hyperparameter controllers; Bayesian optimization for discrepancy design; training-time metrics for variance/bias tracking. Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable proxies for downstream performance; stable search spaces; compute budget for controller training.

- Sector: Hardware Acceleration Use case: Efficient kernels and special functions Application: Accelerate KSD/MMD via GPU kernels for IMQ/Gaussian, fast approximations of Kummer functions, and random-feature Stein kernels; fuse pairwise computations to reduce quadratic overhead. Tools/products: CUDA/ROCm kernels; vendor-supported ML ops; compiler-level fusion. Assumptions/dependencies: Numerical stability in BF16/FP16; verified approximations for high-dimensional regimes; integration with major DL frameworks.

- Sector: Real-time/Continual Learning Use case: On-device continual SSL with low variance Application: Variance-aware sliced regularization (adaptive slice/knots) for streaming setups (AR/VR, drones); periodic geometry audits with KSD/MMD to prevent drift/collapse. Tools/products: Adaptive quadrature/slice schedulers; streaming-friendly regularization APIs; edge MLOps telemetry. Assumptions/dependencies: Efficient on-device compute; robust augmentation under changing environments; memory-friendly estimators.

- Sector: Energy/Industrial IoT Use case: Predictive maintenance from unlabeled visual/sensor data Application: Heavy-tailed KSD to capture rare failure modes; geometry-aware encoders enabling robust downstream anomaly detection and forecasting. Tools/products: SSL pretraining pipelines for sensor-camera fusion; anomaly scoring dashboards; maintenance scheduling integrations. Assumptions/dependencies: Modality fusion priors; long-horizon validation; domain-specific augmentation catalogs.

- Sector: Security/Robustness Use case: Geometry-driven robustness to adversarial and spurious shifts Application: Explore whether heavy-tailed kernels and priors yield embeddings less sensitive to adversarial perturbations and spurious correlations; incorporate geometry audits as part of robust training. Tools/products: Robust SSL benchmarks; certification-like tests based on KSD/MMD; training recipes for tail-sensitive geometry. Assumptions/dependencies: Formal robustness analyses; integration with adversarial training; careful evaluation across diverse datasets.

- Sector: Policy/Governance Use case: Standards for SSL training stability and data efficiency Application: Develop reporting standards for discrepancy choices (kernel, prior, slice/knots), stability metrics, and compute/bias-variance tradeoffs; encourage label-efficient pretraining in public sector datasets. Tools/products: Model cards documenting geometry decisions; best-practice guides for data augmentation and divergence selection. Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder consensus; reproducible benchmarks; alignment with privacy and fairness guidelines.

- Sector: Education Use case: Curriculum on kernel/IPM/Stein-based SSL Application: Teaching modules and labs showcasing spectral representations, slicing vs unsliced tradeoffs, and geometry-tailored regularization with practical coding exercises. Tools/products: Open-source notebooks and datasets; visualization of embedding geometries under varying kernels/priors. Assumptions/dependencies: Accessible implementations; simplified derivations and demos; institutional support for hands-on ML courses.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.