Toward Training Superintelligent Software Agents through Self-Play SWE-RL (2512.18552v1)

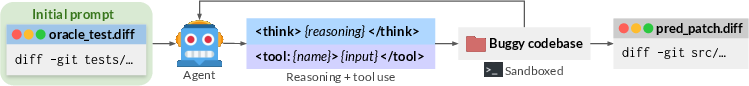

Abstract: While current software agents powered by LLMs and agentic reinforcement learning (RL) can boost programmer productivity, their training data (e.g., GitHub issues and pull requests) and environments (e.g., pass-to-pass and fail-to-pass tests) heavily depend on human knowledge or curation, posing a fundamental barrier to superintelligence. In this paper, we present Self-play SWE-RL (SSR), a first step toward training paradigms for superintelligent software agents. Our approach takes minimal data assumptions, only requiring access to sandboxed repositories with source code and installed dependencies, with no need for human-labeled issues or tests. Grounded in these real-world codebases, a single LLM agent is trained via reinforcement learning in a self-play setting to iteratively inject and repair software bugs of increasing complexity, with each bug formally specified by a test patch rather than a natural language issue description. On the SWE-bench Verified and SWE-Bench Pro benchmarks, SSR achieves notable self-improvement (+10.4 and +7.8 points, respectively) and consistently outperforms the human-data baseline over the entire training trajectory, despite being evaluated on natural language issues absent from self-play. Our results, albeit early, suggest a path where agents autonomously gather extensive learning experiences from real-world software repositories, ultimately enabling superintelligent systems that exceed human capabilities in understanding how systems are constructed, solving novel challenges, and autonomously creating new software from scratch.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching a coding AI to get much better by practicing on real software projects without people feeding it tasks or answers. The AI learns through “self-play,” which means it makes its own coding challenges by adding bugs to real programs, then tries to fix those bugs. Over time, it gets better at both making realistic problems and solving them. The goal is to move toward “superintelligent” software agents that can understand, improve, and even build complex software mostly on their own.

Key Objectives

Here are the main questions the researchers wanted to answer:

- Can a coding AI learn and improve by creating its own problems (bugs) and solving them in real code projects, without human-written issues or tests?

- Will this self-play approach beat training methods that rely on human-curated data and tasks?

- Which ways of creating bugs lead to the best learning (for example, deleting code vs. undoing past edits)?

- Does giving the bug-maker feedback from the bug-fixer help it create better training problems?

How They Did It (Methods)

To keep things simple for a 14-year-old reader, think of this as a two-player game where both players are the same AI, just wearing different “hats.”

The Playground: Real Code Worlds

- The AI works inside “sandboxed” code environments (like safe mini-computers in a box, called Docker images). Each sandbox has a real project with all its software dependencies already installed.

- No one gives the AI a list of tasks, a step-by-step guide, or even how to run the tests—it has to figure those out by exploring.

Two Roles: Builder-of-Bugs and Fixer-of-Bugs

- Bug-injection role: The AI explores a codebase, figures out how to run its tests, and creates a formal “bug artifact.” That artifact is a bundle of files that:

- Add a bug (a code patch that breaks something).

- Provide a test script to run the project’s tests.

- Include a test parser (a small program that reads test output and reports which tests pass or fail).

- List the original test files to protect (so the AI can’t cheat by changing them).

- Weaken some tests (temporarily) to hide the bug from existing checks. The reverse of this weakening acts like a “rule sheet” that tells the fixer exactly what should be true after the bug is fixed.

- Bug-solving role: The same AI, now as the fixer, sees only the reversed test-weakening patch—which serves as a precise specification of what the program should do—and tries to repair the code so all tests pass.

Making a Fair Bug Puzzle

Before the AI sends a bug to the fixer role, the bug must pass “consistency checks,” like:

- Do the tests and parser actually work?

- Does the bug cause some tests that used to pass to fail (and not just break everything)?

- Does weakening tests hide the bug in a realistic way?

- Is each changed file truly part of the problem (not random edits)?

These checks make sure the bug is a real, meaningful challenge—think like making a puzzle that’s neither broken nor trivial.

How the AI Learns: Rewards (Trial and Error)

Reinforcement learning (RL) means learning from practice and feedback:

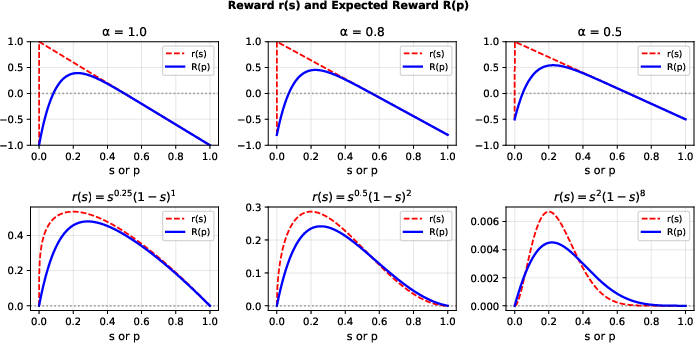

- The bug-maker gets more points for creating bugs that are “just right”—not impossible, not trivial, but challenging and solvable.

- The bug-fixer gets points when all the tests pass after its patch.

- Because the maker wants harder bugs and the fixer wants easier ones, the two roles push each other toward better performance—like a coach and athlete pushing each other to improve.

Making Tougher Problems: Higher-Order Bugs

Sometimes the fixer fails. Those failed attempts are turned into new, more realistic bugs—like layers of edits that went wrong—so the AI learns to deal with multi-step, real-world mistakes.

What They Found (Results)

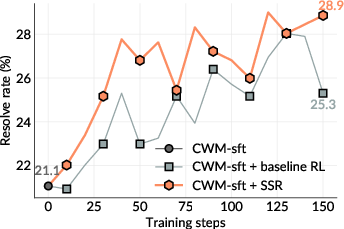

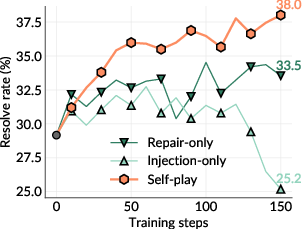

- The self-play system (called SSR) improved itself noticeably on two tough benchmarks:

- SWE-bench Verified: +10.4 points improvement.

- SWE-Bench Pro: +7.8 points improvement.

- SSR consistently beat a strong baseline that used human-written issue descriptions and human-curated tests. In other words, learning from self-made, code-grounded tasks worked better than learning from human-made tasks.

- Self-play (doing both bug-making and fixing) was better than training only the bug-maker or only the fixer.

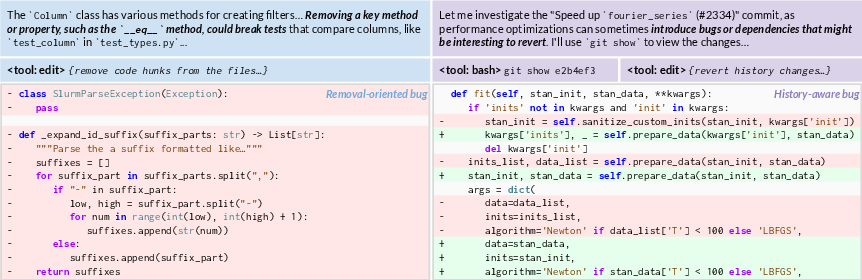

- How you inject bugs matters:

- Naive “just change a line” often produced trivial problems that didn’t help learning.

- Removing chunks of code forced the fixer to rebuild logic and was more educational.

- Mixing removal with “undoing past changes” (using git history) produced the best training challenges—more realistic and diverse.

- Using the fixer’s solve rate as extra feedback to the bug-maker helped only slightly. The biggest gains came from the overall self-play setup itself.

Why It Matters (Implications)

This work shows a path toward coding AIs that don’t rely heavily on people to set up tasks, write issues, or maintain large curated datasets. Instead, the AI can:

- Explore real codebases.

- Create meaningful problems that match its current skill level.

- Practice fixing those problems.

- Continuously learn without waiting on new human-labeled data.

If this continues to scale, we could see agents that understand complex systems better than humans, tackle new kinds of software challenges, and eventually build complete, high-quality software from scratch with minimal guidance.

Conclusion and Potential Impact

In simple terms: they taught an AI to become a stronger coder by letting it make its own practice problems inside real projects and then fix them. This self-play method beat traditional training that depends on human-written tasks. It’s an early but promising step toward super-smart software agents that can keep improving on their own.

Limitations to keep in mind:

- The system relies on tests to judge correctness, which can miss real-world goals or invite overfitting to specific tests.

- It used one model for both roles; separating them or using larger models could help.

- Writing clear natural-language issues automatically is still hard.

- Large-scale training can be unstable and needs more research.

Overall, this paper suggests that autonomous, code-grounded practice could be a powerful way to grow future software AIs beyond what’s possible with human-curated data alone.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, phrased as concrete, actionable items for future research.

- Dependence on existing tests in repositories: SSR’s consistency checks require original test files to exist and be a superset of weakened tests. Assess SSR’s applicability to repos with sparse or no tests, and develop robust, agentic test synthesis that includes public/private test splits to prevent reward hacking.

- Verification fidelity beyond unit tests: The framework uses unit tests as the sole oracle. Integrate higher-level goals (e.g., end-to-end behaviors, integration tests, property-based tests, fuzzing) and quantify whether agents overfit to narrow unit-test specifications.

- Specification leakage and overfitting risk: The reversed test-weakening patch exposes explicit specs to the solver. Measure and mitigate spec overfitting (e.g., metamorphic testing, adversarial test generation, hidden/private tests, randomized checks).

- Cross-language and framework generality: The agent must discover test commands and run diverse test frameworks. Evaluate SSR on polyglot repositories, non-Python ecosystems (e.g., Java/JUnit, JS/Jest, C/C++/CTest), heterogeneous build systems (Maven/Gradle, npm, Bazel), and different OS environments.

- Bug diversity and realism: Current injection focuses on code removal and historical change reversion. Quantify realism and diversity of generated bugs (taxonomy coverage: concurrency, performance, memory, security, API migrations), and design injection strategies that create non-deletion, non-trivial semantic bugs.

- Higher-order bug design: Only up to second-order bugs are considered. Systematically study deeper orders, deduplication criteria, curriculum scheduling, and the trade-off between complexity and solvability; measure how higher-order bugs affect learning and potential drift from original repo correctness.

- Adversarial self-play dynamics with shared policy: Both roles share parameters, enabling possible collusion or implicit coordination. Compare shared vs. separate policies, cross-play among heterogeneous models, population-based training, and formal convergence analyses to avoid dominant strategies that stall progress.

- Reward signal limitations: Solve-rate feedback is noisy and weak, yielding small gains. Investigate richer reward designs (step-level shaping, partial credit for subgoals, verification penalties for brittle fixes, uncertainty-aware or confidence-calibrated rewards) and their impact on stability and sample efficiency.

- Training stability and scalability: Training exhibited instability at scale (gibberish outputs). Identify stabilizing regimes (optimizer choice, gradient clipping, entropy regularization, KL control, off-policy bounds, rollout group size), and provide cost-performance curves and reproducible seeds for robust scaling.

- Evaluation breadth and transfer: Results are limited to SWE-bench Verified and Pro with single attempts and no test-time scaling. Evaluate on larger, fresher, and more diverse corpora (SWE-rebench, SWE-Gym, R2E-Gym), multi-attempt/ranking setups, and measure transfer to natural-language issue resolution and broader software tasks.

- Practical environment assumptions: SSR assumes Docker images with dependencies preinstalled. Explore automated, scalable environment creation (dependency resolution, reproducible builds, caching), and assess SSR robustness on repos with flaky builds, missing dependencies, or non-standard tooling.

- Test discovery and parser reliability: The agent synthesizes test_script.sh and test_parser.py across frameworks. Benchmark parser correctness, failure modes, and portability; consider standardized, framework-aware parsers or toolkits to reduce brittleness.

- Integrity and regression detection: Passing specified tests may still introduce regressions. Add differential testing against original behavior, change-impact analysis, coverage tracking, and regression detectors to ensure holistic correctness beyond targeted specs.

- Difficulty estimation and curriculum control: There is no principled metric for bug difficulty beyond observed solve rates. Develop difficulty predictors, target-matching curricula, and online calibration strategies to maintain bugs in the “challenging yet solvable” regime.

- Repair-only vs. self-play data dynamics: Repair-only underperforms, but the causal factors are unclear. Design controlled experiments with matched bug distributions to isolate the benefits of evolving online curricula and quantify data-efficiency differences.

- Prompt sensitivity and automated evolution: Injection outcomes vary with prompts (direct vs. removal vs. history-aware). Systematize prompt design search, implement automated prompt evolution/optimization, and measure how prompt changes reshape bug distributions and learning.

- Role of natural language specifications: Attempts to synthesize NL issues failed. Explore hybrid specifications (structured + concise NL), quality-controlled NL generation with explicit rewards (clarity, consistency, non-redundancy), and measure transfer improvements on NL benchmarks.

- Model capacity and architecture: Only a single 32B dense model is used. Evaluate larger and MoE models, role-specialized policies, and routing strategies, and study how capacity/architecture affect self-play dynamics, stability, and generalization.

- Security and ethical considerations: SSR generates intentional bugs and fixes. Establish safeguards to avoid creating or propagating vulnerabilities, implement red-teaming and filtering for dangerous edits, and define ethical guidelines for releasing self-play artifacts.

- Reproducibility and artifact standardization: Standardize the format, metadata, and provenance of self-play bug artifacts (patches, tests, parsers, weakened specs) and environment images; open-source these with deduplication and quality metrics to enable community comparison and reproduction.

Glossary

- Absolute Zero: A self-play training approach where a model proposes tasks to maximize its own learning progress without external data. "Absolute Zero~\cite{zhao2025absolutezeroreinforcedselfplay} trains a single reasoning model to propose coding tasks that maximize its own learning progress and improves reasoning by solving them."

- agentic reinforcement learning (RL): Reinforcement learning focused on enabling autonomous, tool-using agents to act and learn in environments. "software agents powered by LLMs and agentic reinforcement learning (RL)"

- agentic scaffolds: Frameworks where an LLM controls decision-making and tool use to solve tasks within an environment. "Agentic scaffolds~\cite{yang2024sweagent,wang2024openhands} involves an LLM driving the core decision-making process based on its tool-mediated interaction with the sandboxed environment."

- bug artifact: A standardized bundle of files (patches, tests, scripts) that formally defines and validates a specific bug and its fix. "A bug artifact that passes the consistency checking is considered valid and is presented to the solver agent,"

- bug-injection agent: The policy role that introduces bugs into a codebase by creating bug artifacts for training. "the same LLM policy is divided into two roles: a bug-injection agent and a bug-solving agent."

- bug-injection patch: The code patch that introduces the bug into the repository as part of the artifact. "The bug-injection patch bug_inject.diff must produce a minimum number of changed files, controlled by the parameter min_changed_files."

- Code World Model (CWM): An open-weight code-focused LLM and tooling scaffold used as the base model and environment interface. "We use Code World Model (CWM), a state-of-the-art open-weight 32B code LLM for agentic software engineering, as our base model."

- consistency validation: Automated checks ensuring a generated bug artifact is meaningful, reproducible, and aligns with specified constraints. "if consistency validation fails"

- containerized environment: A self-contained software environment packaged (e.g., via containers) that provides a consistent runtime for agents. "Both roles have access to the same containerized environment and set of tools, such as Bash and an editor,"

- Docker image: A pre-built container snapshot that encapsulates a repository and its dependencies for execution. "In practice, each input to SSR consists solely of a pre-built Docker image."

- execution-based reward: A reinforcement signal derived from running code/tests to verify behavior rather than from static proxies. "using pure RL on containerized software environments with execution-based reward."

- fail-to-pass tests: Tests that initially fail in the buggy state but are expected to pass after a correct fix. "including pass-to-pass and fail-to-pass tests"

- git diff patch: A patch in unified diff format (produced by git) that modifies repository files. "a git diff patch that introduces bugs into the existing codebase."

- higher-order bugs: Bugs constructed from failed repair attempts, producing layered error states that mimic real multi-step development issues. "we further incorporate higher-order bugs in training the solver agent,"

- inverse mutation testing: A validation technique that checks each modified file is necessary to trigger observed test failures by reverting files individually. "Inverse mutation testing: this check verifies that each file in the bug-injection patch is necessary to trigger the bug."

- Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): A model architecture that routes inputs to specialized expert components to increase capacity efficiently. "Future work should explore larger Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models to understand how capacity and architecture affect self-play learning,"

- mutation testing: A method that assesses test suite quality by introducing small code changes (mutations) and checking if tests detect them. "This approach inverts traditional mutation testing~\cite{mutationtesting},"

- off-policy steps: Training updates using data generated by an older version of the policy, potentially causing staleness. "discard rollouts with more than 8 off-policy steps,"

- oracle test files: The authoritative test files used to evaluate correctness, which are restored to prevent tampering. "test_files.txt: a list of oracle test files that are always reset to their original version before running the test suite."

- pass-to-pass tests: Tests that pass both before and after fixing, used to ensure no regressions are introduced. "including pass-to-pass and fail-to-pass tests"

- reward-hacking behaviors: Undesirable strategies that exploit the reward mechanism (e.g., overfitting specific tests) rather than solving the intended task. "may enable agents to develop reward-hacking behaviors (e.g., overfitting the specific set of tests) rather than genuine bug-fixing capabilities."

- rollouts: Executed trajectories where the agent interacts with the environment to gather experience for RL. "with 64 GPUs for training and 448 GPUs for rollouts."

- sandboxed environment: An isolated execution setting that safely contains code and tools for interaction without affecting the host system. "the bug-injection agent receives a sandboxed environment of a raw codebase."

- self-play: A training paradigm where the agent generates and solves its own tasks to improve autonomously. "a single LLM agent is trained via reinforcement learning in a self-play setting"

- Self-play SWE-RL (SSR): The paper’s proposed framework where a single policy alternates between injecting and repairing bugs to learn from self-generated tasks. "we propose Self-play SWE-RL (SSR), a first step toward superintelligent software engineering agents"

- solve rate: The proportion of solver attempts that successfully fix a given bug. "Let denote the solve rate, defined as the fraction of solver attempts that successfully fix the bug entirely."

- SWE-bench Verified: A human-verified subset of SWE-bench used for reliable evaluation of software bug-fixing agents. "On the SWE-bench Verified and SWE-Bench Pro benchmarks, SSR achieves notable self-improvement"

- SWE-Bench Pro: A more complex, enterprise-oriented extension of SWE-bench focusing on realistic software tasks. "On the SWE-bench Verified and SWE-Bench Pro benchmarks, SSR achieves notable self-improvement"

- SWE-RL: An open RL method for improving LLMs on software engineering tasks using rule-based rewards and software data. "SWE-RL~\cite{wei2025swerl} is the first open RL method to improve LLMs on software engineering tasks using rule-based rewards and open software data."

- test parser: A script that converts raw test outputs into structured results (e.g., JSON pass/fail mapping). "Test parser validity: the test parser test_parser.py, which is used throughout subsequent validation steps, must reliably convert raw test output into a detailed JSON mapping"

- test-time scaling: Inference-time techniques (e.g., multiple attempts or ranking) used to boost performance at evaluation. "We perform one attempt for each problem without parallel test-time scaling or ranking."

- test-weakening patch: A patch that disables or relaxes tests to hide a bug, whose reversal serves as the solver’s formal specification. "we see only the reversed test-weakening patch as a formal specification of the required behavior"

- verifiable rewards: RL rewards grounded in objective checks (e.g., tests passing) rather than subjective judgments. "reinforcement learning (RL) with verifiable rewards has become the focal point."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are actionable applications that can be deployed now, derived from the paper’s Self-play SWE-RL (SSR) framework, its artifacts, and empirical findings.

- Self-play QA augmentation in CI/CD

- Sectors: software, DevOps, QA; Audience: industry

- Use case: Integrate a “challenger–solver” loop in pre-merge pipelines. The injector proposes realistic bugs (via code removal or history-aware reversion), the solver attempts fixes, and inverse mutation checks validate that tests catch meaningful failures. Weak tests are identified by test-weakening reversal, prompting improvements.

- Tools/products/workflows: GitHub Actions/Bitbucket Pipelines integration; “Bug Artifact Kit” (test_script.sh, test_parser.py, bug_inject.diff, test_weaken.diff); inverse mutation test stage; automated PR comments suggesting test additions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Dockerized sandbox of the repo and dependencies; reproducible test execution; sufficient compute for multi-attempt evaluation; organizational policy to keep SSR confined to sandboxes (no direct production writes).

- Automated test runner and parser generation

- Sectors: software tooling; Audience: industry, academia

- Use case: Standardize test execution across heterogeneous repos by auto-creating test_script.sh and test_parser.py, enabling consistent pass/fail accounting and downstream tooling (ranking, triage).

- Tools/products/workflows: Language-agnostic test parser library with adapters; “discover-and-execute” scripts; telemetry for flaky-test detection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to repo and installed dependencies; basic test conventions discoverable by the agent (or minimal human hints).

- Inverse mutation testing toolkit

- Sectors: QA, software engineering research; Audience: industry, academia

- Use case: Assess test suite adequacy by verifying that each buggy file contributes to observable failures and that restoring individual files changes test outcomes. Helps prioritize test work where coverage is weak.

- Tools/products/workflows: CLI and API for per-file reversion runs; dashboards of test sensitivity; integration with coverage tools.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Deterministic test runs; sufficient failing tests to analyze; version-controlled repos (for patch application).

- Synthetic bug/task generation for model training

- Sectors: AI software, ML ops; Audience: industry, academia

- Use case: Produce large, diverse, executable tasks (SWE-bench-like instances) without human issue labels. Use SSR to scale internal corpora for RL fine-tuning of proprietary code models.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Self-play training farm” on Kubernetes; deduplication and solvability filters; data cards for provenance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: GPU capacity; sandboxed containers for proprietary repos; guardrails against data leakage (git history reset).

- Repository onboarding assistant

- Sectors: developer productivity; Audience: industry, daily life (developers)

- Use case: Agents automatically discover how to build/run tests, generate runnable scripts, and surface minimal specs (e.g., reversed test-weakening patches) to help new contributors quickly reproduce failures and iterate.

- Tools/products/workflows: IDE extension (VS Code/JetBrains) with SSR-powered “discover tests” and “spec from tests” functions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Local Docker or devcontainer setup; permissioned access to repo; reliable tool scaffold (bash/editor).

- Education: auto-generated repair assignments and curricula

- Sectors: education; Audience: academia, daily life (students)

- Use case: Create layered bug-fix labs with higher-order bugs that emulate realistic multi-step repair. Calibrate difficulty via solve-rate targets.

- Tools/products/workflows: LMS integration; per-student sandboxes; analytics on error modes and progress.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Institution compute or cloud credits; curated repo set suitable for instruction; safety controls (no malicious code injection).

- Benchmarking without human issue labels

- Sectors: research; Audience: academia

- Use case: Build reproducible, executable benchmarks for agent evaluation using SSR artifacts (tests as formal specs). Reduce reliance on ambiguous natural-language issues while maintaining real repo grounding.

- Tools/products/workflows: Public benchmark hosting with task regeneration; standardized result parsing and solve-rate reporting.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community acceptance of spec-first tasks; transparent validation pipelines.

- Brittle-test detection and improvement suggestions

- Sectors: QA, reliability; Audience: industry

- Use case: Use test-weakening patches and their reversal to locate brittle assertions and missing oracles; recommend strengthening tests in high-risk modules.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Test Hardener” bot posting patches to refine checks; sensitivity maps combining inverse mutation data.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable CI; governance around automated recommendations; owners to approve suggested test changes.

- Training schedule and curriculum design insights

- Sectors: AI engineering; Audience: industry, academia

- Use case: Adopt self-play rather than repair-only pipelines for sustained improvement. Prefer removal + history-aware bug strategies over naive direct injection to avoid trivialities.

- Tools/products/workflows: RL ops playbooks; strategy toggles; solve-rate calibration dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: RL infrastructure with rollout capacity; acceptance of transient instability; monitoring for reward hacking.

- Open-source maintenance support

- Sectors: open-source ecosystems; Audience: industry, daily life (maintainers)

- Use case: SSR agents propose bug artifacts showing failing paths and minimal specs for fixes, helping maintainers triage issues faster and focus reviews on substantive patches.

- Tools/products/workflows: Maintainer bots that generate artifacts and checks; automated labels (“spec-provided,” “inverse-mutated”).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear contribution guidelines; sandboxed execution on forked environments for safety.

Long-Term Applications

Below are applications that likely require further research, scaling, safety controls, or broader organizational buy-in before deployment.

- Autonomous software creation and evolution

- Sectors: software, platforms; Audience: industry

- Use case: Agents that not only fix bugs but continuously propose and implement features, refactors, and migrations—self-creating specs via test-weakening reversal and validating with adversarial self-play.

- Tools/products/workflows: Self-play DevOps platform; multi-context rollouts; long-horizon planning; artifact governance (public/private test splits).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scalable RL with stable training; robust guardrails to avoid reward hacking; verification beyond unit tests (goal-level or system tests).

- Enterprise-scale self-play training on proprietary codebases

- Sectors: enterprise software, ML platforms; Audience: industry

- Use case: Train org-specific “house engineers” (LLM agents) on internal repos with evolving curricula. Achieve repository-specialized competence exceeding generalist agents.

- Tools/products/workflows: Data governance layers; decontamination; compliance-ready audit trails of artifacts and training decisions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strong privacy/security measures; MoE models or larger capacity; diverse repo portfolios to avoid overfitting.

- Automated security red-teaming for code

- Sectors: cybersecurity; Audience: industry, policy

- Use case: Aggressive, history-aware bug injection to simulate realistic failure and vulnerability scenarios; solver role attempts repairs; results guide secure coding standards and patches.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Red Team Agent” integrated with SAST/DAST; exploit-aware specs; attack surface maps produced from inverse mutation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strict sandboxing; ethical use policies; integration with vulnerability databases and disclosure processes.

- Standards for formal, artifact-based software specifications

- Sectors: policy, software standards; Audience: policy, industry

- Use case: Codify test-script, parser, injection, and weakening patches as a portable specification format for AI-assisted development and verification; enable certification and auditability.

- Tools/products/workflows: Specification registries; conformance tests; SBOM-like artifacts for AI-generated changes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder standards bodies; interoperability across languages/frameworks.

- Goal-level verification beyond unit tests

- Sectors: software, robotics, healthcare, finance; Audience: industry, academia

- Use case: Move from unit-test-only rewards to goal-oriented validation (business KPIs, safety goals) for mission-critical systems (e.g., trading engines, medical devices, autonomous robots).

- Tools/products/workflows: Scenario simulators; formal methods + empirical tests; multi-tiered oracles (public/private).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain-specific validators; robust simulation fidelity; regulatory approval in sensitive sectors.

- Multi-step, interdependent workflows (migrations and large refactors)

- Sectors: enterprise software; Audience: industry

- Use case: Agents plan and execute complex version migrations (e.g., framework upgrades), handling staged test expectations and partial specs across sessions.

- Tools/products/workflows: Multi-context memory; automated context compaction; dependency impact analysis; staged CI gates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable long-horizon RL; tool support for cross-session state; strong rollback mechanisms.

- Public–private test split governance to counter reward hacking

- Sectors: policy, QA; Audience: industry, policy

- Use case: Adopt governance models with hidden test splits and randomized checks to ensure agents generalize rather than overfit to oracles.

- Tools/products/workflows: Compliance checkers; “hacking detectors” (e.g., content-based patch heuristics); rotating private test sets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational buy-in; processes for refreshing hidden tests; auditable agent behaviors.

- Repository-specialized agent teams (role separation)

- Sectors: software; Audience: industry, academia

- Use case: Separate policies for injector and solver roles (or multi-agent MoE) to improve specialization and co-evolution dynamics.

- Tools/products/workflows: Role-specific prompts, skills, and memory; negotiation protocols; curriculum orchestration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Larger model capacities; scalable training stability; coordination frameworks.

- Cross-language test interpreter framework

- Sectors: tooling; Audience: industry, academia

- Use case: Unified test parsing and execution across languages/frameworks with minimal assumptions, simplifying adoption of self-play across polyglot stacks.

- Tools/products/workflows: Extensible parser SDK; adapters for major frameworks; standardized JSON outputs for solve-rate analytics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community contributions; maintenance across ecosystem changes.

- Regulatory and ethical frameworks for AI code agents

- Sectors: policy, compliance; Audience: policy, industry

- Use case: Create guidelines for safe self-play in enterprise settings (e.g., sandbox-only, disclosure of generated artifacts, audit trails) and certification of agent outputs.

- Tools/products/workflows: Audit tooling; provenance tracking (data cards); compliance dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Alignment with sector-specific regulations; third-party certification bodies; incident response protocols.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.