Propose, Solve, Verify: Self-Play Through Formal Verification (2512.18160v1)

Abstract: Training models through self-play alone (without any human data) has been a longstanding goal in AI, but its effectiveness for training LLMs remains unclear, particularly in code generation where rewards based on unit tests are brittle and prone to error propagation. We study self-play in the verified code generation setting, where formal verification provides reliable correctness signals. We introduce Propose, Solve, Verify (PSV) a simple self-play framework where formal verification signals are used to create a proposer capable of generating challenging synthetic problems and a solver trained via expert iteration. We use PSV to train PSV-Verus, which across three benchmarks improves pass@1 by up to 9.6x over inference-only and expert-iteration baselines. We show that performance scales with the number of generated questions and training iterations, and through ablations identify formal verification and difficulty-aware proposal as essential ingredients for successful self-play.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching an AI to write correct computer programs all by itself, without relying on human-written training data. The key idea is “self-play”: the AI makes new coding challenges, tries to solve them, and uses a strict checker to see if its solutions are truly correct. The authors use formal verification—a mathematical way to prove programs are right every time, not just on a few tests—to make self-play work reliably for code.

Goals and Questions

The paper asks:

- Can we make a LLM improve at writing code using only self-play, with no human-written answers?

- If we use formal verification (a strong, math-based checker) instead of unit tests (small example checks), does self-play work better?

- What parts of the self-play process matter most for success, like how we create new problems or how we train the solver?

How They Did It (Methods, explained simply)

Think of this system like a three-player team:

- The Proposer: creates new coding problems.

- The Solver: tries to write code that meets the problem’s rules.

- The Verifier: the strict referee that checks if the code is truly correct for all inputs, not just a few examples.

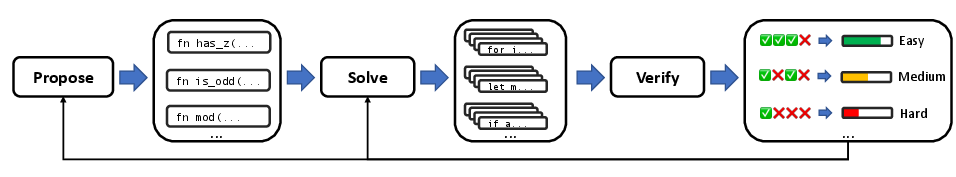

They call the approach “Propose, Solve, Verify” (PSV). Here’s how the loop works:

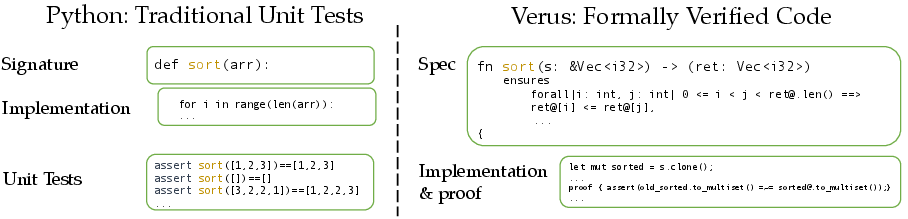

- Propose: The proposer generates formal specifications (clear rules about what the program must do). A spec includes preconditions (what inputs are allowed) and postconditions (what must be true about the output).

- Solve: The solver tries multiple solutions for each spec.

- Verify: A formal verifier (using Verus, a system for verifying Rust code) checks each solution. If it passes verification, it’s guaranteed to be correct.

- Learn: The solver is trained only on the verified, correct solutions (this is called “rejection fine-tuning”: you reject any solution that fails and only learn from the good ones).

- Repeat: The proposer makes new problems, guided by the solver’s current skills.

Two important tricks:

- Difficulty-aware proposing: The proposer adjusts problem difficulty (Easy, Medium, Hard, Impossible) based on how often the solver passes on similar problems. If the solver starts doing well, the proposer makes harder challenges; if not, it offers more appropriate ones.

- Formal verification instead of unit tests: Unit tests check a few examples (like a quiz with a few questions). Formal verification is like proving a math theorem—it guarantees the program is correct for all inputs if it passes.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

What they found:

- Using formal verification makes self-play work much better for code. It stops the solver from “cheating” by gaming unit tests and prevents bad solutions from being used for training.

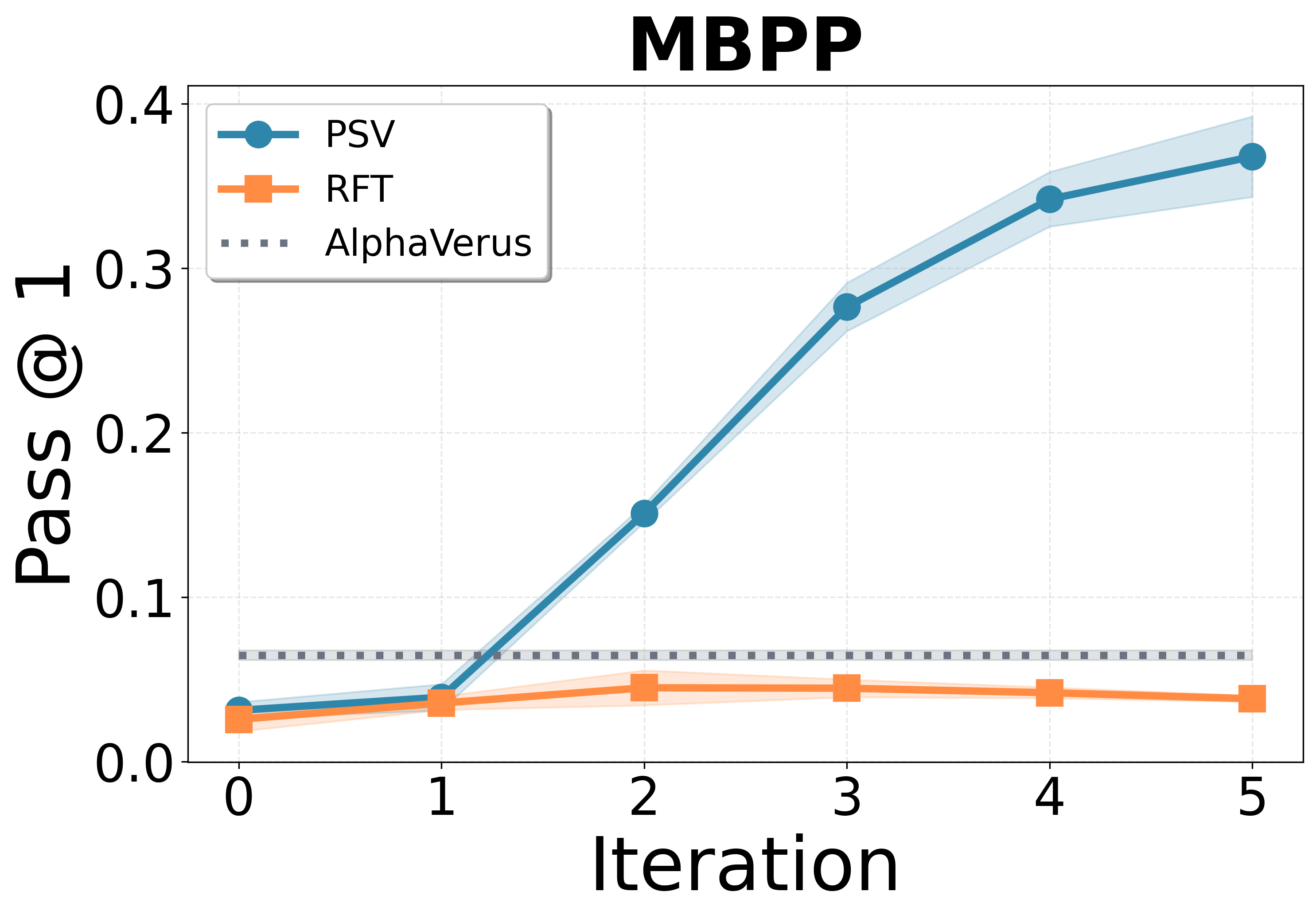

- Their model, called PSV-Verus, beats strong baselines:

- Compared to inference-only methods (like AlphaVerus) and training without proposing new problems (RFT), PSV-Verus improves success rates by up to about 9.6× in some settings.

- Performance grows smoothly when you:

- Generate more problems per round (more practice helps).

- Run more self-play rounds (iterative training helps).

- Ablation tests (turning features off to see what breaks) show:

- Removing verification causes big drops in accuracy and wastes compute on unsolvable problems.

- Removing difficulty-awareness or reducing diversity in proposed problems also hurts performance.

Why this matters:

- It shows that self-play can work for real programming tasks when you have a strong checker.

- It reduces dependence on expensive, hard-to-scale human-made datasets.

- It points to a path for AI systems to teach themselves safely and steadily.

Implications and Potential Impact

- Safer code generation: Formal verification is used in safety-critical software (like operating systems) because it provides guarantees. Bringing this to AI training means we can trust its outputs more.

- Scalable self-improvement: The AI can grow by making its own curriculum—creating and solving new problems—without needing people to write or grade them.

- Beyond coding: The idea could extend to any domain where a reliable verifier exists (like formal math proofs), enabling broader self-play learning.

- Research direction: The results suggest focusing on better proposers (for controlling difficulty) and stronger verifiers can unlock more powerful self-play systems.

In short, the paper shows that combining self-play with formal verification can train code-writing AI models to get better on their own, safely and reliably, and that the process scales well as you add more problems and rounds of training.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of unresolved issues and concrete opportunities for future work arising from the paper.

- Portability beyond Verus: Validate PSV on other sound verification ecosystems (e.g., Dafny, Lean/Coq, Why3, Viper) to assess generality across languages, tooling, and proof styles.

- Handling verifier incompleteness: Quantify the rate and impact of false negatives and “unknown” outcomes in Verus, and design training strategies that don’t discard potentially correct solutions due to incomplete verification.

- Verification robustness: Characterize verifier timeouts, nondeterminism, and resource limits; introduce outcome triaging (pass/fail/unknown), time-budget policies, and caching to stabilize training signals.

- Spec quality assurance: Move beyond syntactic spec validation to detect vacuous, trivial, contradictory, or unsatisfiable specifications; define and enforce semantic quality metrics for proposed specs.

- Difficulty estimation accuracy: Replace solver pass-rate as a proxy for difficulty with calibrated predictors using spec/proof features (e.g., SMT query complexity, invariant count, proof length), and validate their predictive power.

- Adaptive curriculum design: Learn thresholds and target difficulty mixtures (instead of fixed τE/τM and uniform sampling) to maximize solver learning progress over iterations.

- Proposer learning: Train the proposer’s parameters (not just in-context prompting) via supervised or RL objectives tied to downstream solver improvement; study stability and avoidance of degenerate/spec-bleeding behaviors.

- Diversity and coverage controls: Introduce novelty/coverage objectives (AST diversity, spec template coverage, logical pattern diversity) and grammar-constrained decoding to reduce duplication and invalid generations.

- Semantic deduplication: Upgrade from textual dedup to semantic equivalence (AST normalization, spec canonicalization, solver-in-the-loop equivalence checks) to reduce redundant training examples.

- Spec exploitation guardrails: Detect and prevent proposer-solver “collusion” where specs become overly permissive or trivial to satisfy; add checks for constraint tightness and non-trivial postconditions.

- Scaling laws and compute trade-offs: Systematically quantify performance scaling with model size, proposal budget, number of iterations, and few-shot context length; identify diminishing returns and optimal budget allocation across proposing vs. solving.

- RL alternatives to RFT: Benchmark on-policy RL methods (e.g., GRPO/PPO with verifiable rewards) adapted to sound-but-incomplete verifiers, including advantage assignment under uncertain verification outcomes.

- Efficiency of solving: Explore guided search (tree-of-thought, beam search with verifier-in-the-loop, proof planning), early-stopping heuristics, and reuse of partial proofs to reduce solving cost.

- Broader evaluation metrics: Track proof length/complexity, verification time, implementation efficiency (runtime/memory), and code/readability metrics alongside pass@k to capture quality beyond binary correctness.

- Real-world program complexity: Evaluate on larger, multi-module, stateful Rust projects (I/O, concurrency, unsafe code interfaces), and measure how PSV handles dependencies and cross-function proofs.

- Cross-domain generalization: Test transfer beyond Dafny2Verus→MBPP/HumanEval on diverse, industrial or domain-specific verified corpora to assess overfitting to the synthetic spec distribution.

- Natural-language-to-spec alignment: Investigate generation of formal specs from natural-language prompts and measure semantic alignment with human intent; compare PSV-trained solvers on such tasks.

- Unknown outcome integration: Treat “unknown” verifier results explicitly (e.g., secondary checkers, heuristic confidence, delayed re-verification) rather than mapping all non-pass outcomes to fail in training.

- Few-shot prompting cost vs. benefit: Quantify the trade-off between adding more in-domain few-shot examples and solving runtime; develop retrieval strategies to select informative exemplars efficiently.

- Acceptance criteria for proposed specs: Define principled filters beyond syntactic validity (e.g., satisfiability checks, minimal witness generation, non-vacuity proofs) before adding specs to the training pool.

- Proposal objective formalization: Optimize proposer behavior for “learning progress” (e.g., expected gain in solver performance) rather than difficulty alone; estimate progress signals from solver updates.

- Reproducibility and sensitivity: Run broader sensitivity analyses over seeds, base models, τ thresholds, k_trn/k_prop/B/T, and prompting templates to assess robustness of PSV’s gains.

- Dataset representativeness: Audit topic and structure coverage of generated specs (algorithms, data structures, numeric/proof-heavy tasks) to ensure balanced curricula and to identify underrepresented areas.

- Failure mode monitoring: Develop detectors for drift toward unhelpful or adversarial specs, stagnation in solver improvements, or curriculum collapse; design automatic recovery mechanisms.

Glossary

Below is an alphabetical list of advanced domain-specific terms drawn from the paper, each with a brief definition and a verbatim example of how it is used in the text.

- Advantage-weighted algorithms: Reinforcement learning methods that weight updates by estimated advantages, which can misbehave under noisy or incomplete rewards. "meaning that advantage-weighted algorithms could incorrectly punish models for correct solutions that were judged to be incorrect."

- AlphaVerus: A prior state-of-the-art prompting-based method for verified code generation in Verus. "AlphaVerus, which relies on the same seed corpus but without self-play."

- Binary guarantee of correctness: A property of verification that yields a definitive pass/fail signal with no partial credit. "formal verification provides a binary guarantee of correctness."

- Difficulty-aware proposer: A generator that conditions on estimated problem difficulty to produce specifications matched to the solver’s current level. "We design a difficulty-aware proposer that adapts the difficulty of proposed specifications based on the solver's current pass rates."

- Ensures clause: A postcondition section in a specification stating required properties of outputs. "ensures clause saying that the vector is sorted"

- Expert iteration: A training paradigm where a solver improves iteratively using increasingly strong guidance (experts or verified outputs). "a solver trained via expert iteration."

- Expectation-maximization: An iterative optimization framework; here, used to interpret rejection fine-tuning as offline RL via EM. "can be seen as an offline RL algorithm based on expectation-maximization."

- Few shot prompting: Supplying a small number of exemplars in the prompt to steer generation. "We follow AlphaVerus's few shot prompting setup"

- Formal specification: A mathematically precise description of valid inputs and required output behavior for a program. "generate problems in the form of formal specifications"

- Formal theorem proving: Machine-checked proof construction in formal logic systems. "domains such as formal theorem proving"

- Formal verification: Mechanically checking program correctness against specifications, typically via a verifier. "formal verification provides a sound reward signal: if the verifier accepts the program, then the program is guaranteed to satisfy its specification for all inputs."

- GRPO: A reinforcement learning algorithm variant referenced as an alternative to RFT. "such as GRPO"

- In-context learning: Conditioning model behavior on examples provided in the prompt without parameter updates. "propose a difficulty-aware proposer based on in-context learning."

- Loop invariants: Properties that must hold before and after each loop iteration to enable verification of correctness. "e.g., “loop invariants”"

- Offline RL: Reinforcement learning from fixed datasets of trajectories without on-policy exploration. "can be seen as an offline RL algorithm based on expectation-maximization."

- On-policy RL: Reinforcement learning that updates a policy using data sampled from the current policy. "Future work on on-policy RL algorithms for formally verified self-play may investigate more performant RL algorithms in this setting."

- Pass rate: The fraction of sampled solutions for a problem that successfully pass verification. "using the pass rate (how many candidate solutions passed verification for each problem) as a proxy"

- Pass@: A metric estimating the probability that at least one of k sampled solutions is correct. "We adopt the widely used Pass@ metric"

- Postcondition: A requirement that must hold for outputs after a function executes, as specified formally. "postcondition (here, the ensures clause saying that the vector is sorted)"

- Precondition: A requirement on inputs that must hold before a function executes, as specified formally. "preconditions (here, just the type constraint of )"

- Rejection Fine-Tuning (RFT): A method that fine-tunes only on verified or accepted outputs, rejecting failures. "rejection fine-tuning (RFT)"

- Reward hacking: Exploiting imperfections in reward signals to increase rewards without genuinely solving tasks. "vulnerable to reward hacking"

- Self-play: A training paradigm where models generate their own tasks and learn from attempts to solve them, guided by verification. "Training models through self-play alone (without any human data) has been a longstanding goal in AI"

- SMT-backed proofs: Proofs checked using Satisfiability Modulo Theories solvers to ensure logical validity of specifications and code. "SMT-backed proofs into mainstream systems languages such as Rust"

- Soundness (verifier): The property that if the verifier accepts a program, the program truly meets the specification. "the Verus verifier is guaranteed to be sound but not complete"

- Specification verifier: A tool that checks whether a specification itself is well-formed and valid before solving. "filtered through a spec verifier which ensures that the spec defines a valid set of mathematical pre- and post-conditions."

- Test-time training (TTT): Adapting a model during evaluation by training on tasks available at test time. "a setting that we refer to as test-time training (TTT)"

- Turing-complete: A language capable of expressing any computation given enough resources. "SMT-backed verification provides a sound guarantee over a Turing-complete language (Rust)."

- Verifier: A function or tool that returns whether code satisfies a specification. "A verifier checks whether the code meets the formal specification."

- Verus: A Rust-based framework enabling formal verification with specifications and machine-checkable proofs. "Verus, a framework that enables formal verification of Rust programs"

Practical Applications

Summary

Drawing on the paper’s Propose, Solve, Verify (PSV) framework—self-play for code generation anchored by formal verification (Verus for Rust)—the applications below translate its findings into concrete tools, workflows, and initiatives. Each item names likely sectors, indicative products, and key assumptions or dependencies.

Immediate Applications

- Verified coding assistant for Rust

- Sectors: Software, DevTools, DevSecOps, Safety-Critical (aerospace, automotive, medical devices), Infrastructure

- What: An IDE/CI assistant that proposes Verus specs, generates implementations plus proofs, and only accepts solutions passing the Verus verifier; difficulty-aware prompts can escalate challenges during internal evaluation.

- Tools/Workflows: VSCode/JetBrains plugin; GitHub Actions “SpecGuard” to gate PRs on verifier pass; pre-commit hooks for spec sanity checking; on-demand test-time training on the repo’s own specs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Code must sit within Verus’s supported Rust subset; high-quality specs are available or can be elicited; verification time is acceptable within CI budgets.

- Self-play data engine for training code LLMs

- Sectors: AI/ML, Software

- What: Use PSV to synthesize large corpora of spec–solution–proof triplets for RFT or RL from verifiable rewards, reducing dependence on scarce human-written formal proofs.

- Tools/Workflows: “PSV-Orchestrator” to generate specs (with difficulty labels), solve, verify, deduplicate; artifacts to fine-tune base code models.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Verifier soundness (Verus) and stable toolchain; compute for repeated sampling and verification; seed specs to kick-start diversity.

- Formal-methods courseware generator and auto-grader

- Sectors: Education (university courses, bootcamps), Corporate training

- What: Difficulty-aware generation of Verus problems (Easy/Medium/Hard), verified reference solutions, and instant, machine-checkable grading.

- Tools/Workflows: “Verus Tutor” web app; LMS integration for assignments and automated feedback; analytics on pass rates to tune curricula.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable parsing/spec verification filters; institutional willingness to adopt Verus-based assignments.

- Verified component libraries and refactoring assistants

- Sectors: Libraries (collections, crypto, parsing), Systems software

- What: Generate or refactor small Rust modules with embedded specs and proofs (e.g., sorting, bounds-checked data structures, simple crypto utilities), guaranteeing contract adherence.

- Tools/Workflows: Library scaffolder that proposes specs from short NL descriptions; batch “verify-and-promote” pipeline for internal component catalogs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Target functionality fits Verus’s subset; proofs remain maintainable as APIs evolve.

- Security- and compliance-oriented development gates

- Sectors: FinTech, Healthcare IT, Industrial control, Government IT

- What: Use verifier pass/fail as a policy gate on code that touches safety/security boundaries; retain verifier logs and proof artifacts for audits.

- Tools/Workflows: “ProofTrace” archival of verification outcomes; policy-as-code to require proofs for selected modules (e.g., bounds, memory safety, critical invariants).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Organizational buy-in; defined scope where formal guarantees are feasible; auditor acceptance of SMT-backed proofs.

- Adversarial evaluation and robustness testing for code LLMs

- Sectors: AI/ML evaluation, Model governance

- What: Generate hard, diverse, verifier-backed tasks to stress-test code assistants and detect reward hacking that would be missed by unit tests.

- Tools/Workflows: Difficulty-aware “SpecFuzzer” that tracks pass rates and proposes edge cases; dashboards showing failure clusters.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Coverage is bounded by Verus language subset; tests target spec satisfaction, not emergent non-functional properties (e.g., performance).

- Project-specific specialization via test-time training (TTT)

- Sectors: Software teams, Open-source repos

- What: Run PSV locally on repo-specific specs to adapt a small code model (e.g., 3B) to the project’s patterns and proof idioms without human labels.

- Tools/Workflows: One-click TTT job in CI; cache of verified local exemplars for few-shot prompts; periodic retraining as specs grow.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Compute availability; stable specs within the project; legal clearance to use on internal code.

- Benchmark and dataset curation for verified coding

- Sectors: Academia, Open-source, Evaluation labs

- What: Expand and maintain Verus benchmarks (HumanEval-Verified, MBPP-Verified) with principled proposal, spec verification, and de-duplication.

- Tools/Workflows: Continuous dataset building pipeline; metadata on difficulty distributions and solver pass curves.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Community governance for dataset quality; license compliance for derivatives.

- Proof engineering helpers (loop invariants, ghost code)

- Sectors: Formal methods, DevTools

- What: Suggest missing invariants and auxiliary lemmas during verification failures; re-run until verifier accepts.

- Tools/Workflows: “ProofLint” to extract counterexamples/hints from SMT feedback and propose patches; tight IDE integration.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Verifier diagnostics are accessible and informative; models can be prompted effectively on failure traces.

- Procurement and pilot projects for verification-first AI coding

- Sectors: Public sector, Critical infrastructure contractors

- What: Pilot RFPs that request machine-checkable proof artifacts on selected modules; evaluate bid feasibility using PSV-generated baselines.

- Tools/Workflows: Template RFP clauses referencing verifier pass as acceptance criteria; small proof-of-concept repos demonstrating end-to-end flow.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Legal acceptance; scope selection that’s feasible with today’s Verus subset and model capabilities.

Long-Term Applications

- End-to-end autonomous software agents with propose–solve–verify loops

- Sectors: Software, Robotics, Embedded systems

- What: Agents that draft specs from NL requirements, implement, verify, and iterate—escalating difficulty automatically—across sizable codebases.

- Tools/Workflows: Multi-agent build systems where “Spec Agent,” “Code Agent,” and “Verifier Agent” coordinate; continuous self-play in the background.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Broader language coverage (beyond Verus subset), strong spec elicitation from ambiguous requirements, scalable verification.

- Cross-language verified code generation

- Sectors: Systems (C/CompCert/Frama-C), SPARK/Ada, Dafny/C#, Move/SMT for smart contracts

- What: Port PSV to ecosystems with sound verifiers to synthesize verified modules across languages.

- Tools/Workflows: Language adapters; unified “Verifier API” to plug into SAT/SMT, proof assistants (Isabelle/Coq/Lean).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of sound verifiers; comparable or better completeness; tooling maturity across ecosystems.

- Verified smart contract synthesis and auditing

- Sectors: Finance/DeFi, Enterprise blockchains

- What: Propose and synthesize contracts and proofs against formal specs (safety, liveness, invariants), reducing exploit risk.

- Tools/Workflows: PSL/Move/Why3-based specs; on-chain deployment gates requiring proof artifacts; “SpecFuzzer” for adversarial properties.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Sound, widely accepted verifiers for target languages; alignment with auditor standards; gas and performance constraints.

- Safety-critical controllers with proof-backed guarantees

- Sectors: Robotics, Automotive, Aerospace, Industrial automation, Healthcare devices

- What: Synthesize controllers satisfying formal constraints (bounds, monotonicity, fail-safes) and generate proofs of invariants.

- Tools/Workflows: Hybrid PSV + control synthesis; plant-model-aware verification (e.g., integrating reachability tools).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Richer specification languages for continuous dynamics; integration with domain-specific verifiers.

- Hardware design via property-checked self-play

- Sectors: Semiconductors, EDA

- What: Apply PSV-like loops to RTL/HDL with formal property checkers (SAT/SMT) to synthesize blocks satisfying assertions.

- Tools/Workflows: “PSV-RTL” to propose properties, implement modules, and run bounded/unbounded model checking.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Scalable property checking; well-formed property sets; synthesis–verification co-design loops.

- Organization-wide “proof-as-a-service” pipelines

- Sectors: Enterprise software, Cloud platforms, MSPs

- What: Shared platforms that convert policy plus requirements into specs and continuously verify critical services; proofs as auditable artifacts.

- Tools/Workflows: Central “ProofHub” with APIs; dashboards for coverage, proof debt, difficulty distribution; automated escalations.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Cultural adoption; standardized spec templates; cost-effective verification at scale.

- Regulatory frameworks for verifiable AI-generated code

- Sectors: Government, Standards bodies, Insurance

- What: Standards specifying when machine-checkable proofs are required and how verification artifacts should be produced and retained.

- Tools/Workflows: Certification schemes; artifact schemas; audit tooling integrated into CI/CD and model training logs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Consensus on verifier trust; jurisprudence for liability; sector-specific profiles (e.g., MISRA-like for Rust+Verus).

- General reasoning self-play anchored to sound verifiers

- Sectors: Mathematics (theorem proving), Scientific computing, Operations research

- What: Extend proposer–solver loops to theorem provers and constraint-solvers where correctness can be mechanically checked.

- Tools/Workflows: Cross-domain curriculum engines mixing formal math and code; unified pass-rate difficulty management.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Strong, scalable verifiers/provers; robust spec/proof synthesis beyond code.

- Reduced human data dependence for frontier LLM training

- Sectors: AI labs, Open-source ML ecosystems

- What: Scale self-play with verifiable rewards to bootstrap stronger reasoning in code models without massive human-curated datasets.

- Tools/Workflows: Cluster-scale PSV orchestration; active-learning loops for verifier-guided exploration.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Compute scaling; preventing mode-collapse/diversity loss; managing verifier incompleteness in RL.

- National-scale education in formal reasoning

- Sectors: Public education, Professional certification

- What: Personalized tutors generating targeted exercises and proofs; credentialing based on verifier-backed assessments.

- Tools/Workflows: Adaptive curricula driven by pass-rate telemetry; shared open datasets; teacher dashboards.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Ease-of-use for learners; accessible tooling; alignment with curricula and accreditation bodies.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Verifier properties: Soundness is critical; incompleteness can misclassify correct solutions and complicate on-policy RL. Toolchain stability (SMT solver versions) matters.

- Language coverage: Today’s Verus supports a subset of Rust; broader industrial use needs expanded coverage and better prover ergonomics.

- Spec quality: High-quality, non-ambiguous specifications are a bottleneck; automated spec elicitation from NL remains a hard problem.

- Compute and cost: PSV involves sampling and verification; production adoption needs cost-aware batching, caching, and priority queues.

- Integration: Smooth IDE/CI integration, artifact management, and developer UX (interpretable errors, invariant suggestions) are essential for uptake.

- Governance: For policy/regulatory use, standardized artifact formats and auditor acceptance criteria must be defined.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.