In Pursuit of Pixel Supervision for Visual Pre-training (2512.15715v1)

Abstract: At the most basic level, pixels are the source of the visual information through which we perceive the world. Pixels contain information at all levels, ranging from low-level attributes to high-level concepts. Autoencoders represent a classical and long-standing paradigm for learning representations from pixels or other raw inputs. In this work, we demonstrate that autoencoder-based self-supervised learning remains competitive today and can produce strong representations for downstream tasks, while remaining simple, stable, and efficient. Our model, codenamed "Pixio", is an enhanced masked autoencoder (MAE) with more challenging pre-training tasks and more capable architectures. The model is trained on 2B web-crawled images with a self-curation strategy with minimal human curation. Pixio performs competitively across a wide range of downstream tasks in the wild, including monocular depth estimation (e.g., Depth Anything), feed-forward 3D reconstruction (i.e., MapAnything), semantic segmentation, and robot learning, outperforming or matching DINOv3 trained at similar scales. Our results suggest that pixel-space self-supervised learning can serve as a promising alternative and a complement to latent-space approaches.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching computers to “see” using only pixels—the tiny colored dots that make up an image—without relying on human labels or text. The authors present Pixio, a simple but powerful way to pre-train vision models by hiding parts of images and asking the model to fill them in. They show that, with the right setup and a lot of diverse images, this pixel-based learning can match or beat popular methods that learn from abstract features instead of raw pixels.

Key Objectives

The paper explores a few simple questions:

- Can a model learn strong, general visual skills just by predicting missing pixels in images?

- How can we make this pixel-prediction task challenging enough so the model truly understands images, not just copies nearby colors?

- If we train on billions of internet images with almost no human labeling, does it still work?

- Compared to leading methods (like DINOv2/v3), how well does this approach do on real tasks such as estimating depth from a single image, reconstructing 3D scenes, segmenting images into meaningful parts, and helping robots learn?

Methods and Ideas, Explained Simply

The basic idea: learning by “repairing” images

Imagine a jigsaw puzzle where large pieces of the picture are covered. A model looks at the visible parts and tries to guess what’s hidden. If it can accurately “paint in” the missing areas, it must have learned about shapes, textures, lighting, materials, and even what objects are likely to appear together. This is called self-supervised learning because the model learns from the image itself, not from human-written labels.

What is an autoencoder?

An autoencoder has two parts:

- The encoder: like a great note-taker, it looks at the visible parts and makes a compact summary.

- The decoder: like a skilled artist, it uses that summary to repaint the missing pixels.

Masked autoencoders (MAEs) remove many patches of the image before encoding, then ask the decoder to rebuild the missing pieces. Using a high “masking ratio” (hiding a lot of the image) makes the task hard, which forces real understanding.

What Pixio changes and why

The authors found the original MAE design wasn’t ideal for very large models and very large datasets. They made a few focused upgrades:

- Deeper decoder: The “artist” (decoder) gets more layers so it can handle detailed pixel reconstruction. This lets the “note-taker” (encoder) focus on learning useful visual features, not just low-level details.

- Larger mask blocks: Instead of hiding single tiny patches, Pixio hides bigger chunks (like 4×4 patches at a time). This stops the model from cheating by copying nearby pixels and encourages learning real structure.

- More class tokens: Think of class tokens as extra “global notebooks” where the model stores high-level summaries (scene type, style, camera angle). Using several, not just one, helps capture different kinds of global information.

- Web-scale training with soft self-curation: They trained on about 2 billion web images. To avoid overfitting to boring or overly simple images (like plain product shots or text-heavy pictures), they use:

- Loss-based sampling: Images the model struggles to reconstruct are sampled more often (they’re more informative).

- Color-entropy filtering: Images with very low color variety (often text-heavy) are downweighted.

Together, these changes keep the task challenging, the model capable, and the data diverse—without heavy manual curation.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

Across several tasks, Pixio performs as well as or better than top alternatives that use more complicated “latent-space” objectives (like DINOv3):

- Monocular depth estimation: From a single photo, the model predicts how far things are. Pixio gives better accuracy on popular indoor datasets and competitive results elsewhere.

- Feed-forward 3D reconstruction: From pairs of images, the model helps recover 3D structure and camera poses. Pixio consistently improves reconstruction quality, even though it learned from single images during pre-training.

- Semantic segmentation: The model classifies each pixel (for example, sky vs. building vs. road). Pixio matches or beats strong baselines, especially when fine details matter.

- Robot learning: On a suite of robot control tasks, Pixio outperforms several competitors, suggesting its features transfer well to action and decision-making.

Why this is important:

- Pixel-based training is simple, stable, and efficient. It doesn’t need tricky tricks like contrastive pairs, special stabilizers, or handcrafted invariances.

- It captures both low-level details (textures, edges, lighting) and higher-level meaning (objects, scenes). This blend is especially helpful for geometry-heavy tasks like depth and 3D.

- It scales to web data with minimal human labeling, which reduces bias from specific benchmarks and makes it future-proof as data grows.

Implications and Impact

This work shows that learning directly from pixels can be a powerful and scalable path to visual intelligence. Instead of depending on human-written labels or complex training setups, a model can learn a lot by trying to rebuild what it cannot see. The approach:

- Offers a strong, less biased alternative to popular latent-space methods.

- Complements existing techniques—some tasks may benefit more from pixel modeling, others from abstract feature learning, and combining them could be even better.

- Points toward training large, general-purpose vision systems on massive, diverse, lightly curated web data, which can then be used for many real-world applications: robotics, 3D mapping, AR/VR, and more.

Takeaway

By making the reconstruction task tougher, the decoder stronger, the global summaries richer, and the data broader (but not over-curated), Pixio shows that “learning to paint the missing pixels” remains a simple, reliable, and remarkably effective way to teach computers to understand the visual world.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, organized to guide future research.

- Algorithmic trade-offs and scaling laws:

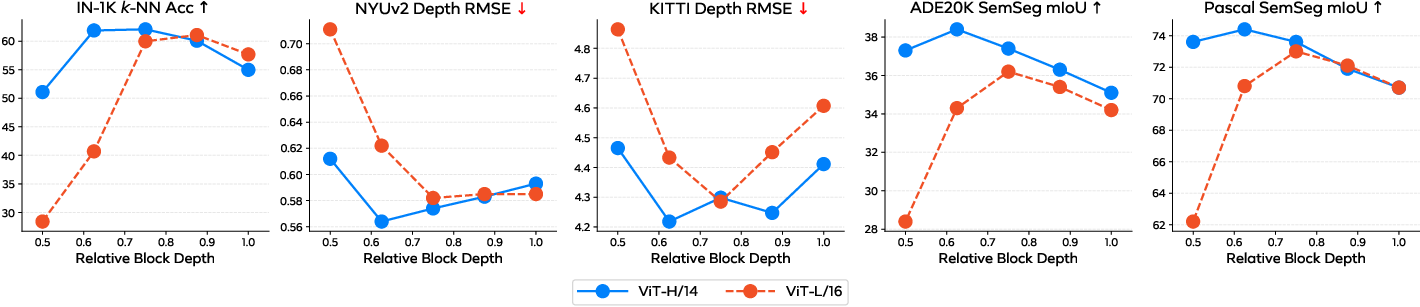

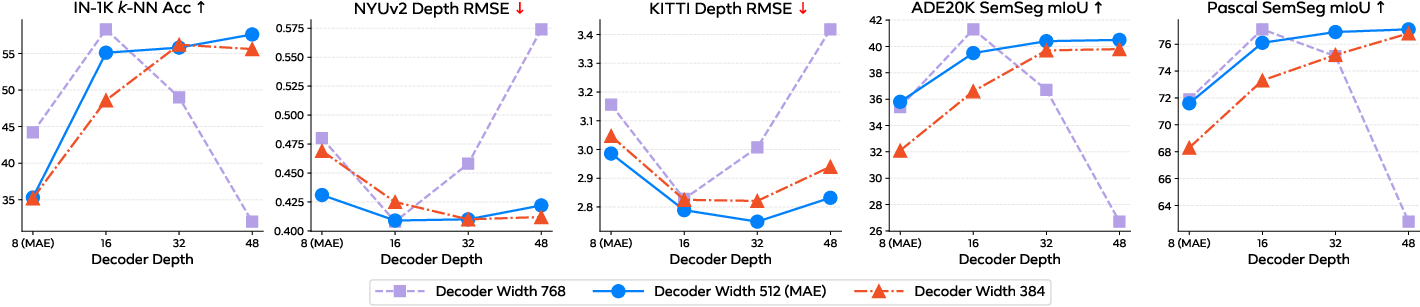

- Quantify the encoder–decoder capacity trade-off: how decoder depth/width affect where the “best” representations live in the encoder, and whether deeper decoders consistently shift optimal features toward later blocks across model scales.

- Establish scaling laws for masking ratio and masking granularity (e.g., 1×1 vs 2×2 vs 4×4 vs 8×8) as a function of patch size, input resolution, and dataset diversity; current results only test a few points and lack principled guidance.

- Systematically evaluate mask shapes and content-aware/dynamic masking (irregular, semantic, edge-aware masks) versus fixed square blocks, including their impact on downstream tasks and leakage shortcuts.

- Objective design and representation properties:

- Specify and ablate reconstruction loss choices (e.g., MSE vs L1 vs perceptual/feature-space losses vs MAE-on-features) and their effect on semantic abstraction versus low-level fidelity.

- Provide empirical evidence and diagnostics for “encoder laziness” and “memorization” when decoders are over-parameterized, including metrics/indicators to detect and prevent these failure modes.

- Analyze invariances induced (or missed) by pixel reconstruction (viewpoint, illumination, texture), and quantify trade-offs with latent/invariant objectives for tasks needing strong semantics (e.g., linear-probe classification).

- Multiple class tokens:

- Determine principled design guidelines for the number and role of class tokens (e.g., specialization into pose/style/scene/semantics), including mechanisms to encourage diversity (orthogonality constraints, auxiliary losses) and task-dependent aggregation strategies (average vs concatenation vs learned pooling).

- Evaluate whether class tokens overlap with or complement ViT register tokens and whether combining both yields better downstream performance.

- Data curation and reproducibility:

- Precisely define reconstruction-loss-based sampling (range/normalization of l_i, acceptance probability function, number of passes, update schedule), and measure how bootstrapping from an initial model biases the final data distribution.

- Quantify the impact of the color-histogram entropy filter (thresholds, failure cases); assess whether it unintentionally filters rare but important domains (e.g., low-light, monochrome, medical).

- Audit and de-duplicate the 2B dataset against evaluation/test sets (NYUv2, KITTI, ADE20K, Pascal VOC, ETH3D, etc.) to rule out contamination and measure OOD robustness under controlled domain shifts.

- Release detailed data pipeline (including filtering thresholds, sampling procedure, and duplicates removal) to support exact reproducibility.

- Efficiency, stability, and compute:

- Provide quantitative training efficiency and stability comparisons with DINOv2/v3 (wall-clock time, GPU hours, memory footprint, throughput) at matched data/model scales; current claims of “simplicity, stability, efficiency” lack measurements.

- Report training dynamics (loss curves, variance across seeds, sensitivity to hyperparameters), failure modes, and recovery strategies at 2B-data/5B-model scale.

- Explore resolution and patch-size scaling (e.g., 256→448→896, 16→14→8), and quantify how they interact with mask granularity and decoder capacity.

- Fairness in comparisons and evaluation breadth:

- Ensure uniform evaluation protocols across baselines (e.g., consistent heads, patch sizes, hyperparameters, data sources), especially where DINOv2 official models and different ViT variants are used; quantify sensitivity to head choices (DPT vs other dense heads).

- Expand benchmarks to tasks requiring high-level semantics and invariance (object detection, instance segmentation, open-vocabulary recognition/retrieval, few-shot classification) to reveal where pixel-only objectives underperform.

- Include robustness tests (corruptions, occlusions, adversarial noise, heavy compression) and OOD generalization beyond the limited zero-shot depth setups.

- Distillation details and effects:

- Describe the distillation procedure (teacher/student objectives, layer mapping, temperature, losses used—pixel vs feature vs logits, augmentation pipeline), and ablate its effect on students’ representation quality and downstream performance.

- Investigate whether distillation preserves or alters the benefits of deeper decoders and masked-block design, and whether students inherit the same optimal encoder-block features.

- 3D and video extensions:

- Validate claims of multi-view/spatial reasoning by evaluating on video self-supervision, multi-view masked modeling, and temporal correspondence; establish whether pixel supervision alone scales to 4D (spatiotemporal) settings.

- Study whether combining single-view pixel pretraining with explicit multi-view/sequence objectives (e.g., epipolar consistency, temporal masking) further improves MapAnything-like tasks.

- Objective hybridization:

- Explore hybrid objectives that combine pixel reconstruction with latent/invariant targets (contrastive, JEPA-style predictive losses) to balance semantics and low-level details; quantify gains on both dense and semantic tasks.

- Examine curriculum strategies (e.g., mask ratio schedules, progressive decoder capacity, perceptual loss annealing) to steer representation learning.

- Interpretability and analysis:

- Empirically verify the hypothesized contents of global tokens (pose/style/scene/objects) via probing, CKA/CCA analyses, and controlled interventions; relate to downstream performance contributions.

- Reconcile results with claims that reconstruction can produce uninformative features; provide mechanistic explanations (e.g., what specific design choices prevent representational collapse).

- Robotics and embodiment:

- Test on real-robot, closed-loop control with online adaptation/sample efficiency metrics; analyze whether global vs spatial embeddings are consistently optimal across tasks and whether class-token aggregation choices matter for policy learning.

- Evaluate safety, sim-to-real transfer, and failure analysis under task distributions that differ markedly from web imagery.

- Ethics and governance:

- Assess biases introduced by loss-based sampling and color-entropy filtering across demographic and domain dimensions; develop mitigation strategies.

- Clarify licensing, privacy, and content moderation policies for the 2B web-crawled data; provide procedures for auditability and takedown.

Glossary

- Ablation study: A systematic evaluation that varies one component at a time to assess its impact. "Ablation study of using decoders of different depth (#attention blocks) or width (feature dimension) to train MAE on IN-21K."

- Asymmetric encoder-decoder architecture: A design where the encoder and decoder have different structures or roles, often to separate representation learning from reconstruction. "disentangling visible and masked tokens with an asymmetric encoder-decoder architecture,"

- Autoencoder: A neural network that learns to compress inputs into a latent representation and reconstruct them back. "Autoencoders represent a classical and long-standing paradigm for learning representations from pixels or other raw inputs."

- BERT: A transformer-based masked LLM whose masking idea inspired visual masked modeling. "MAE adapts BERT~\cite{bert} to visual domain."

- Class token: A learned token added to transformer inputs to aggregate global information for tasks like classification. "MAE appends a class token~\cite{bert} alongside patch tokens."

- Contrastive learning: A self-supervised approach that pulls together representations of similar pairs and pushes apart dissimilar ones. "The second category stems from contrastive learning~\cite{Hadsell2006, moco, simclr} and has evolved to incorporate various forms of latent-space objectives"

- Decoder: The network component that reconstructs masked or target signals (e.g., pixels) from encoded features. "We employ a ViT decoder with 512 dimensions and 32 blocks,"

- Denoising autoencoder (DAE): An autoencoder trained to reconstruct clean inputs from corrupted versions, learning robust features. "The first category is represented by denoising autoencoders (DAE)~\cite{vincent2008extracting}, now commonly realized as masked autoencoders (MAE)~\cite{mae} which learn by predicting unknown pixels under structural corruptions."

- DINO: A family of self-supervised methods for vision transformers using latent-space objectives and teacher-student training. "Today, the go-to solution for off-the-shelf self-supervised learning models is typically DINO and its extensions,"

- DINOv2: A large-scale, robust self-supervised vision model trained with extensive curated data. "DINOv2~\cite{dinov2} demonstrates large-scale data with diverse concepts~\cite{vo2024automatic} is essential for learning robust and transferrable representations."

- DINOv3: A state-of-the-art self-supervised vision model leveraging multi-view training and large data. "Pixio clearly outperforms the most capable DINOv3 model under both DPT and linear heads,"

- DPT head (Dense Prediction Transformer): A transformer-based head for dense prediction tasks like depth or segmentation. "Domain-specific monocular metric depth estimation with frozen encoder and a trainable DPT (Dense Prediction Transformer) head or a linear regression head."

- Encoder: The network component that transforms inputs into latent representations used for downstream tasks. "We freeze the pre-trained encoder and add a trainable DPT head~\cite{dpt} or linear regression head on it."

- Feed-forward 3D reconstruction: Predicting 3D structure directly from images without iterative optimization or geometry pipelines. "feed-forward 3D reconstruction (i.e, MapAnything),"

- Ground truth leakage: When the target information becomes too easily inferable from inputs, reducing task difficulty and learning utility. "MAE demonstrates that a high masking ratio (e.g, 75\%) is necessary to avoid ground truth leakage and construct a meaningful pretext task"

- Histogram entropy (in colors): A measure of color distribution complexity; low values often indicate text-heavy or low-variability images. "we filter images with low histogram entropy in colors to reduce text-heavy images,"

- Inductive bias: Built-in assumptions or priors in algorithms/tasks that guide learning toward certain solutions. "The inductive bias from humans implicitly serves as the ground truth guiding models to learn the physical world."

- JEPA (Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture): A self-supervised framework predicting future or masked embeddings in latent space. "(e.g, DINO~\cite{dino}, JEPA~\cite{jepa})."

- k-NN accuracy: Performance metric using k-nearest-neighbor classification on frozen features to assess representation quality. "IN-1K -NN accuracy 35.3 55.8,"

- Latent space: The representation space produced by a model where inputs are encoded into abstract features. "or a latent space produced by models."

- Linear head: A simple linear layer attached to frozen features to evaluate or adapt representations. "We use a linear head for both monocular depth estimation (regression) and semantic segmentation (classification)."

- Linear probing: Evaluating representations by training only a linear classifier on top of frozen features. "``0 block'' corresponds to linear probing."

- Loss-based soft sampling: A data sampling strategy that probabilistically favors examples with higher loss to emphasize harder data. "First, we employ loss-based soft sampling."

- Mask block: A masking scheme that hides contiguous blocks of patches rather than single patches. "Larger mask block."

- Masking granularity: The size of the unit (e.g., 1×1 vs 4×4 patches) used when masking parts of the input during training. "We compare performance under different masking granularity in Figure~\ref{fig:maskgrid}."

- Masking ratio: The proportion of input tokens/pixels that are masked during training in masked modeling. "MAE demonstrates that a high masking ratio (e.g, 75\%) is necessary to avoid ground truth leakage and construct a meaningful pretext task"

- Metric depth estimation: Predicting absolute (metric) scene depth values rather than only relative ordering. "Domain-specific monocular metric depth estimation with frozen encoder and a trainable DPT (Dense Prediction Transformer) head or a linear regression head."

- mIoU (mean Intersection over Union): A standard segmentation metric averaging IoU across classes. "ADE20K mIoU 35.8 40.4."

- Monocular depth estimation: Estimating scene depth from a single RGB image. "including monocular depth estimation (e.g, Depth Anything),"

- Multi-view consistency: A training bias encouraging features to be consistent across different views/augmentations of the same scene. "For latent-space practices, inductive bias (e.g, multi-view consistency~\cite{simclr, dino}) is necessary to prevent model collapse"

- Patch tokens: Tokenized image patches used as inputs to vision transformers. "MAE appends a class token~\cite{bert} alongside patch tokens."

- Pixel-space self-supervised learning: Learning directly from raw pixels by reconstructing or predicting them, rather than using latent targets. "pixel-space self-supervised learning can serve as a promising alternative and a complement to latent-space approaches."

- Reconstruction loss: The objective measuring difference between predicted and ground-truth pixels in masked modeling. "To minimize reconstruction loss, the encoder has to sacrifice some capacity"

- Register tokens (ViT registers): Special tokens in vision transformers that act as persistent memory slots to aid representation. "These tokens relate to ViT register tokens~\cite{darcet2023vision, capi, dinov3}, but serve different roles."

- Relative depth estimation: Predicting ordinal relationships (which point is closer/farther) rather than absolute depth. "we further follow Depth Anything V2~\cite{dav2} to evalute zero-shot monocular relative depth estimation,"

- RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error): A regression error metric measuring the square root of mean squared differences. "reducing RMSE from 0.320 0.268"

- Self-curation: Minimally supervised dataset refinement driven by model feedback (e.g., loss) to improve data quality. "with a self-curation strategy with minimal human curation."

- Self-supervised learning: Learning from unlabeled data using pretext tasks where the supervision signal is derived from the data itself. "Modern methods on self-supervised learning generally fall into two categories,"

- Stop gradient: A technique that prevents gradient flow through parts of the network to stabilize training. "it does not require stabilization mechanisms such as negative samples~\cite{simclr}, stop gradient~\cite{moco}, or careful centering and sharpening~\cite{dino}."

- Train-test distribution shift: A mismatch between training and evaluation data distributions that can harm generalization. "resulting in train-test distribution shift."

- ViT (Vision Transformer): A transformer architecture that processes images as sequences of patch tokens. "Our largest ViT-5.4B/16 model is pre-trained on 2B curated web-crawled images"

- Web-scale data: Extremely large datasets collected from the web with diverse content and minimal curation. "trained on carefully curated web-scale data."

- Zero-shot: Evaluating a model on tasks or datasets without task-specific fine-tuning. "we further follow Depth Anything V2~\cite{dav2} to evalute zero-shot monocular relative depth estimation,"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete, deployable uses that can leverage Pixio’s pixel-space self-supervised pretraining today, along with target sectors, likely tools/workflows, and feasibility notes.

- Vision backbones for dense perception in production

- Sectors: Software, Robotics, AR/VR, Mapping, Geospatial

- What: Swap in Pixio encoders (e.g., Pixio-H/L/B checkpoints) for dense tasks (depth, segmentation) where low-level details matter. The paper shows superior or on-par performance vs. DINOv3 for monocular depth, feed-forward 3D reconstruction, and semantic segmentation.

- Tools/workflow: Load Pixio encoders from the released repo; attach a DPT head for depth or a linear/DPT head for segmentation; export to existing inference services.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to pretrained weights; compatibility with ViT-based pipelines; minor head tuning per domain.

- Feed-forward 3D reconstruction with fewer views

- Sectors: Real estate, Construction/BIM, E-commerce (product digitization), Entertainment/Media

- What: Use Pixio as the encoder in MapAnything-style pipelines to improve two-view reconstruction and pose estimation, accelerating asset capture and inspection with fewer images.

- Tools/workflow: Two-view capture workflow; Pixio encoder + MapAnything training/inference stack; export meshes/point clouds for digital twins or product listings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality camera inputs; proper scale estimation or downstream alignment; compute for point cloud/mesh post-processing.

- AR occlusion and scene understanding on devices

- Sectors: Mobile, AR/VR

- What: Improve monocular depth and segmentation for occlusion handling, virtual object placement, and room understanding in AR apps.

- Tools/workflow: Integrate Pixio-B/L with a light DPT head; quantization/pruning for mobile; on-device or edge inference.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Latency targets may require distillation, quantization, or NPU acceleration; 256×256 pretraining resolution may necessitate multi-scale finetuning.

- Geospatial and remote sensing segmentation

- Sectors: Energy, Agriculture, Urban planning, Insurance

- What: Use Pixio-based segmentation for land use/land cover mapping and urban feature extraction (demonstrated on LoveDA satellite dataset).

- Tools/workflow: Pixio encoder + linear/DPT head; georeferenced tiling; post-processing with GIS tools.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain adaptation for specific sensors (e.g., multispectral); handling large imagery via tiling and stitching.

- Robotics policies with improved visual embeddings

- Sectors: Warehousing, Manufacturing, Consumer robotics, Logistics

- What: Use Pixio embeddings (average of multiple class tokens) in imitation or RL policies to boost task success across benchmarks (CortexBench).

- Tools/workflow: Policy networks consuming global embeddings (no additional CNN needed); behavior cloning/RL training loops with Pixio-frozen encoders.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Closed-loop latency constraints; camera mounting and calibration; environment variation may require modest finetuning.

- Depth label generation for supervision-lite datasets

- Sectors: Autonomy, AR/VR, Robotics, Synthetic data platforms

- What: Generate pseudo depth labels from single images to augment training of downstream detectors/segmenters or multi-task models.

- Tools/workflow: Batch inference with Pixio+DPT; filtering heuristics; re-training downstream models with pseudo-labels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Error-aware training (confidence weighting); avoid domain drift if target domain diverges significantly.

- Bias-resistant pretraining data pipelines

- Sectors: Software platforms, Foundation model labs

- What: Adopt loss-based self-curation (probabilistic sampling by reconstruction loss) and color-histogram-entropy filtering to select diverse, “hard” images at scale with minimal manual curation.

- Tools/workflow: Compute reconstruction loss per image with a bootstrap Pixio model; sample using l_i ≥ U(0,1); filter low color-entropy images; iterate.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Initial model to score images; legal access to web-scale data; monitoring for residual domain skews.

- Faster domain adaptation for dense tasks

- Sectors: Healthcare imaging (non-diagnostic assistance), Industrial inspection, Retail analytics

- What: Finetune Pixio encoders on modest domain data to improve segmentation/depth in specialized environments (e.g., factory floors, store aisles).

- Tools/workflow: Frozen or partially unfrozen encoder with task head; few-shot or low-shot finetuning; active learning loops.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Representative domain samples; compliance constraints in sensitive domains; careful validation to avoid overreach in regulated use.

- Benchmark-neutral model selection for evaluation

- Sectors: Academia, ML Ops

- What: Use Pixio as a complementary baseline to latent-space methods (e.g., DINO) when evaluating dense perception tasks to reduce benchmark-induced bias.

- Tools/workflow: Side-by-side evaluation harnesses across depth/segmentation/3D; report variance under distribution shifts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to diverse test sets; adherence to reproducible evaluation protocols.

Long-Term Applications

These uses require further research, scaling, productization, or ecosystem development before wide deployment.

- General-purpose world models for embodied AI

- Sectors: Robotics, Consumer electronics, Assistive tech

- What: Combine pixel-supervised pretraining with action learning (e.g., VLA stacks) for robust manipulation/navigation in unstructured environments.

- Tools/workflow: Pixio as vision backbone in VLA agents; continual learning on robot-collected data; safety layers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scalable video + action datasets; reliable sim-to-real bridges; safety certification.

- Foundation models for real-time AR glasses

- Sectors: AR/VR, Wearables

- What: On-device, low-latency depth and segmentation under outdoor lighting, motion blur, and power limits.

- Tools/workflow: Hardware-aware architecture search; aggressive distillation and quantization; sensor fusion (IMU, depth).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Next-gen NPUs; thermal budgets; robust multi-scale training.

- City-scale, feed-forward 3D mapping from crowd images

- Sectors: Geospatial, Smart cities, Disaster response

- What: Aggregate few-view reconstructions across crowdsourced photos to update city geometries and aid post-disaster assessments.

- Tools/workflow: Large-scale deduplication and pose graph construction; Pixio-based two-view reconstruction as building block; confidence fusion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data licensing and privacy; geo-localization accuracy; quality control of heterogeneous inputs.

- Autonomous driving perception backbones with minimal manual curation

- Sectors: Automotive

- What: Train driving backbones using pixel-supervised pretraining on web-scale data plus targeted domain adaptation, reducing annotation costs.

- Tools/workflow: Web-scale curation with reconstruction-loss sampling; targeted injection of driving scenes; multi-sensor fusion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Despite promising results elsewhere, Pixio underperforms DINO variants on KITTI in zero-shot; needs domain-tailored curation and finetuning.

- Universal 3D asset creation for metaverse and digital twins

- Sectors: Entertainment, Industrial digital twins, E-commerce

- What: Consumer-grade, few-shot capture generating consistent, textured, metric 3D assets with material and lighting priors.

- Tools/workflow: Pixio + differentiable rendering; PBR material estimation; scene relighting.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Advances in reflectance and material modeling; scale-aligned multi-view capture guidelines.

- Data governance and public datasets for minimal-bias pretraining

- Sectors: Policy, Public research, Standards bodies

- What: Curate and release large, minimally filtered image corpora plus transparent self-curation recipes to reduce benchmark overfitting.

- Tools/workflow: Documentation (datasheets), audits for representational harms, community challenges focused on distribution shift.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal frameworks for web data; funding for hosting and governance; privacy-preserving pipelines.

- Cross-modal extensions with pixel-grounded supervision

- Sectors: Healthcare, Industrial IoT, Remote sensing

- What: Extend pixel supervision to multi-spectral, depth, thermal, or event cameras for robust multimodal representations.

- Tools/workflow: Masked autoencoding on stacked modalities; modality dropout; cross-sensor calibration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to aligned multimodal datasets; handling sensor-specific noise and sampling rates.

- Video-native pixel supervision for temporal reasoning

- Sectors: Sports analytics, Surveillance, Robotics

- What: Masked autoencoding across space-time to learn motion, causality, and long-horizon correspondences for forecasting and control.

- Tools/workflow: Temporal masking schedules; scalable video pretraining; memory-efficient attention.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Efficient video training at scale; dataset licensing; careful bias and privacy controls.

- On-device privacy-preserving personalization

- Sectors: Mobile, Smart home

- What: Personalize depth/segmentation to a user’s environment on-device via lightweight finetuning without sending data to the cloud.

- Tools/workflow: Federated or local finetuning; low-rank adapters; periodic evaluation with private metrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sufficient on-device compute; robust adapter designs; battery constraints.

- Green pretraining practices

- Sectors: Sustainability, Cloud providers

- What: Reduce compute and carbon cost by adopting stable pixel supervision (no negatives or complex losses) plus loss-based data sampling to avoid wasteful training.

- Tools/workflow: Carbon-aware schedulers; curriculum via reconstruction loss; mixed-precision and sparsity.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate energy accounting; alignment with organizational sustainability targets.

- Safety-critical perception with certifiable uncertainty

- Sectors: Healthcare (non-diagnostic), Industrial autonomy, Aviation

- What: Combine Pixio’s dense outputs with calibrated uncertainty for risk-aware decision making in safety-critical settings.

- Tools/workflow: Post-hoc calibration; Bayesian heads; conformance testing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain certification requirements; rigorous validation datasets; explainability tooling.

- Educational and research infrastructure

- Sectors: Academia, EdTech

- What: Use Pixio as a simple, stable baseline to teach self-supervised learning and conduct reproducible ablations on masking granularity, decoder depth, and class tokens.

- Tools/workflow: Course labs leveraging released code/checkpoints; standardized ablation suites; student projects on data curation strategies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Continued availability of open-source assets; compute grants for education.

Notes on general feasibility across applications:

- Compute and model size: While the training is compute-heavy, distilled Pixio variants (B/L/H) support a range of deployment budgets; on-device use may need quantization/distillation.

- Data licensing and ethics: Web-scale pretraining hinges on lawful, ethical data use; organizations must manage privacy, consent, and content provenance.

- Domain gaps: Despite strong generalization, domain-specific finetuning is often required (e.g., automotive).

- Stability and simplicity: Pixel supervision avoids complex loss tricks, easing engineering, but decoder capacity and masking granularity must be tuned to prevent encoder laziness or reconstruction shortcuts.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.