Advantage in distributed quantum computing with slow interconnects (2512.10693v1)

Abstract: The main bottleneck for distributed quantum computing is the rate at which entanglement is produced between quantum processing units (QPUs). In this work, we prove that multiple QPUs connected through slow interconnects can outperform a monolithic architecture made with a single QPU. We consider a distributed quantum computing model with the following assumptions: (1) each QPU is linked to only two other QPUs, (2) each link produces only one Bell pair at a time, (3) the time to generate a Bell pair is $τ_e$ times longer than the gate time. We propose a distributed version of the CliNR partial error correction scheme respecting these constraints and we show through circuit level simulations that, even if the entanglement generation time $τ_e$ is up to five times longer than the gate time, distributed CliNR can achieve simultaneously a lower logical error rate and a shorter depth than both the direct implementation and the monolithic CliNR implementation of random Clifford circuits. In the asymptotic regime, we relax assumption (2) and we prove that links producing $O(t/\ln t)$ Bell pairs in parallel, where $t$ is the number of QPUs, is sufficient to avoid stalling distributed CliNR, independently of the number of qubits per QPU. This demonstrates the potential of distributed CliNR for near-term multi-QPU devices. Moreover, we envision a distributed quantum superiority experiment based on the conjugated Clifford circuits of Bouland, Fitzsimons and Koh implemented with distributed CliNR.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper asks a simple but important question: if the “roads” connecting small quantum computers (called QPUs) are slow, can a group of them working together still beat one big, single quantum computer?

The authors show that the answer can be yes. They design and test a way for multiple QPUs to cooperate even when their connections are slow, and they find that this setup can run certain tasks faster and with fewer errors than a single large QPU.

What questions were they trying to answer?

They focused on three easy-to-understand questions:

- If connecting QPUs is slow, is there still any advantage in using several QPUs instead of one?

- Can a special technique (called CliNR) be redesigned to work well across multiple QPUs?

- How many “connection resources” are needed so the group of QPUs doesn’t get stuck waiting for the slow links?

How did they approach it?

Think of a quantum circuit like a recipe: you apply a sequence of steps (gates) to a set of ingredients (qubits) to get a final dish (the result). Here’s the setup and the approach, explained with simple ideas and analogies.

The hardware setup (distributed vs. monolithic)

- Monolithic (one big QPU): This is like one big kitchen with all the tools and ingredients in one place. Everything is connected and fast.

- Distributed (many QPUs): This is like several smaller kitchens arranged in a ring, each connected only to its two neighbors by slow delivery routes. Each kitchen has:

- A “compute module” (where it cooks),

- A “storage module” (where it keeps special ingredients called Bell pairs),

- An “entanglement module” (where it makes those Bell pairs to share with neighbors).

A Bell pair is a “magic link” between two qubits in different kitchens. Making a Bell pair over the slow connection takes longer than a normal in-kitchen step. The paper studies the case where making a Bell pair takes up to 15 times longer than a normal gate, often focusing on up to 5×.

What is CliNR (the main technique)?

CliNR is a “partial error correction” method. Instead of trying to correct every error (which is expensive), it reduces errors in a smart, lightweight way by preparing, checking, and then using special helper states. It breaks a big circuit into smaller chunks and handles each chunk with these steps:

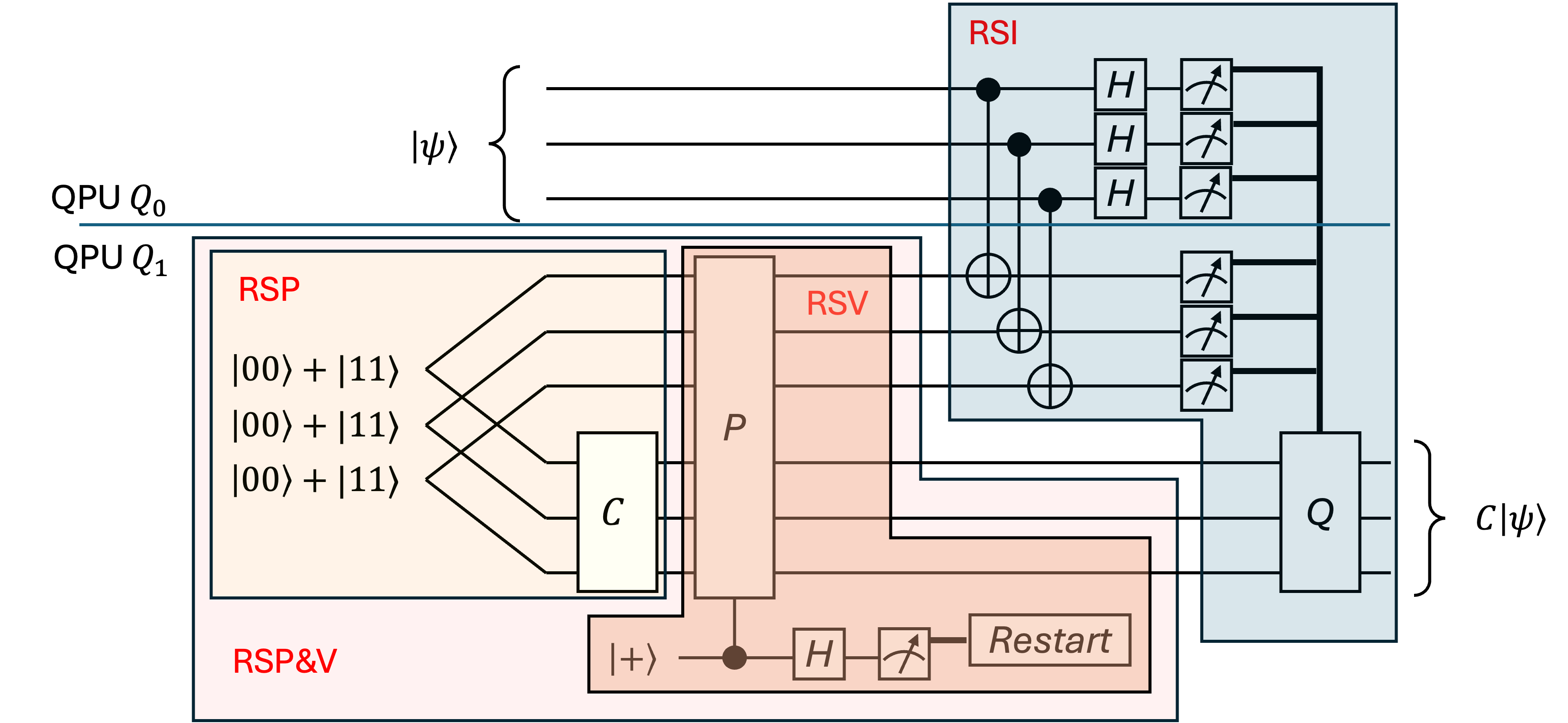

- Resource State Preparation (RSP): Build a helper state offline, like assembling a Lego module ahead of time.

- Resource State Verification (RSV): Perform quick tests to make sure the helper state isn’t broken. If a test fails, scrap it and rebuild.

- Resource State Injection (RSI): Use the good helper state to apply the chunk of the circuit to your data quickly.

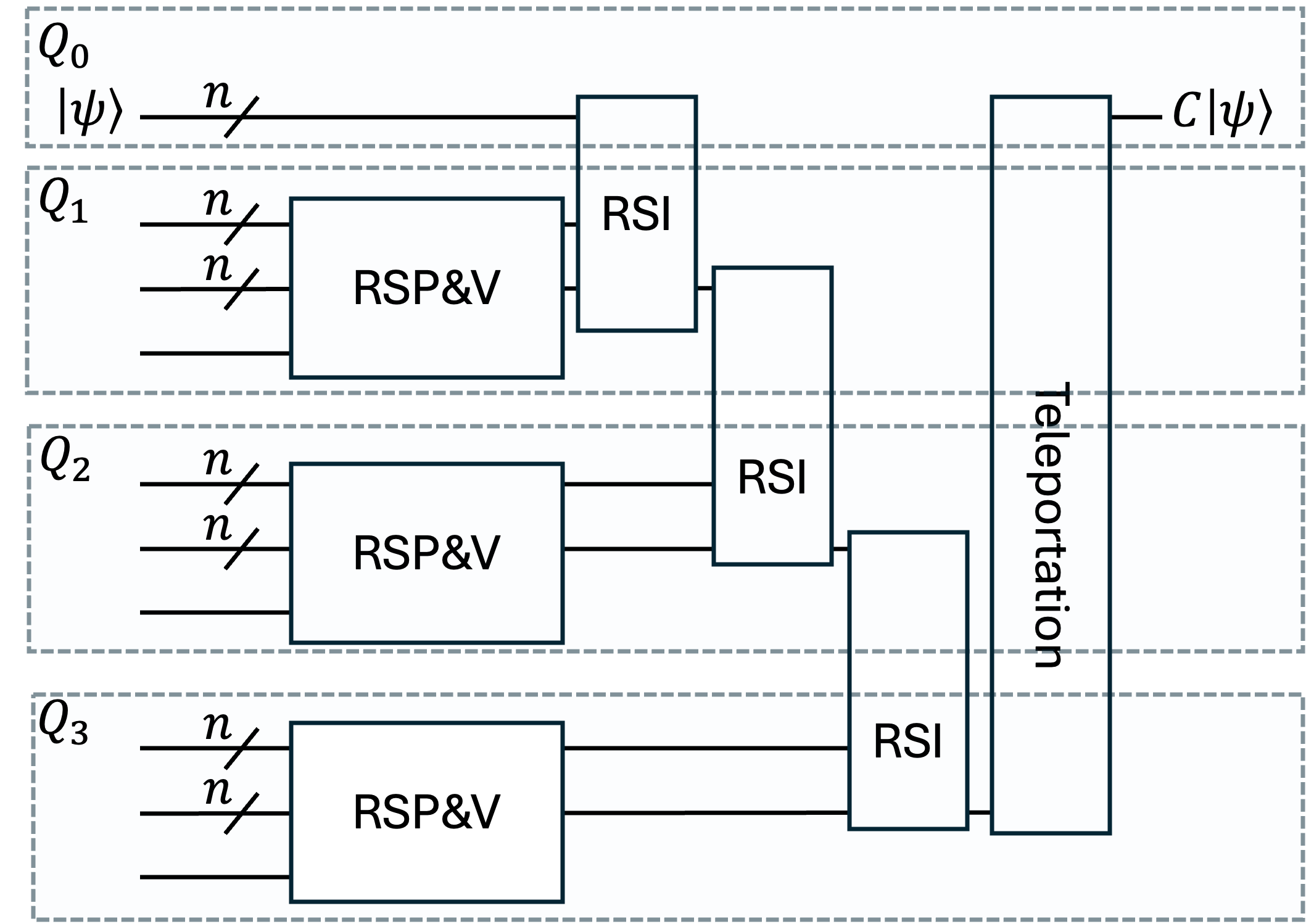

The authors redesign CliNR to run across multiple QPUs. Here’s the key idea:

- Parallel preparation and checking: Each QPU prepares and verifies its chunk’s helper state at the same time, without needing the slow links. This cuts waiting time.

- Serial injection with shared entanglement: Once a helper state is ready, it is “injected” into the data, passing the data from one QPU to the next using remote operations that consume Bell pairs. Because many Bell pairs can be made in advance and stored, the slow links don’t stall the whole process as much.

Important terms explained simply

- Entanglement: A strong, special connection between two qubits. Changing one can affect the other, even far away.

- Bell pair: A standard “entangled pair” used like a shared tool to do remote operations across QPUs.

- Depth: How many layers of steps your circuit takes. Lower depth usually means faster and less error accumulation.

- Logical error rate: The chance the overall output is wrong. Lower is better.

- Clifford circuit: A specific set of quantum operations often used for testing and building other quantum techniques. You don’t need the details—just think of them as a standard type of recipe.

What did they find and why is it important?

Here are the main results:

- In simulations, distributed CliNR beats both:

- The direct method (just run the circuit on one QPU),

- A monolithic CliNR method (run CliNR on one big QPU),

- for random Clifford circuits on around 85 qubits split across 4 QPUs.

- Distributed CliNR gives:

- Lower logical error rates (more accurate results),

- Shorter depth (faster completion),

- even when making entanglement is up to 5 times slower than normal gates.

- Why it works: Most of the needed Bell pairs can be created and stored while helper states are being prepared and checked in parallel. This “front-loading” avoids later stalls during injection.

- Theory result (as systems get bigger): If you slightly relax the rule and allow a few parallel Bell-pair links per neighbor, you only need about O(t / ln t) parallel links for t QPUs to avoid stalling. That means the number of parallel links grows much slower than the number of QPUs, and it doesn’t depend on how many qubits are inside each QPU. This is surprisingly efficient.

This matters because today’s quantum links are much slower than gates inside a QPU. Showing an advantage even with slow links suggests multi-QPU machines can be useful sooner than expected.

What’s the potential impact?

- Near-term promise: Many labs can already build monolithic QPUs, but fast interconnects are hard. This work shows you don’t need very fast links to get benefits. That means multi-QPU systems might outperform single large QPUs sooner, using current or near-future technology.

- Path to quantum advantage: The authors propose using distributed CliNR to help run a special kind of circuit (conjugated Clifford circuits) that is linked to quantum superiority tests—experiments where quantum devices do something classical computers can’t feasibly match.

- Room for improvement: Techniques like better photon collection, quantum memories, or other engineering tricks could make entanglement faster and higher quality, widening the gap in favor of distributed CliNR.

In short, the paper shows a practical way to make several small quantum computers cooperate effectively even with slow connections, and it provides both simulations and theory that explain why this can beat one big quantum computer for important tasks.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to guide future research:

- Quantify the precise advantage threshold as a function of n, t, p, and τ_e: the simulations only explore n ∈ [50,100], t=3, p=10⁻⁴, and show advantage up to τ_e≈5, but the paper does not characterize the full parameter regimes (e.g., critical τ_e beyond which distributed CliNR loses its edge, sensitivity to p, or optimal t for a given n).

- Extend beyond random Clifford circuits: the paper focuses on Clifford circuits and CliNR for Clifford subcircuits; it does not address non-Clifford gates (e.g., T gates), magic-state injection, or hybrid circuits where only parts are Clifford—limiting applicability to general quantum algorithms.

- Provide a formal definition and assessment of the “uniform distribution” assumption used in the asymptotic result: the proof that O(T/ln T) parallel links suffice relies on uniform distribution of subcircuits; the paper does not specify this rigorously nor evaluate non-uniform/adversarial circuit partitions.

- Incorporate realistic interconnect details: entanglement distillation overheads, heterogeneous link fidelities/times, memory-enhanced generation, photon collection improvements, and electron juggling are mentioned but not modeled; their impact on τ_e, error rates, and throughput remains unquantified.

- Model classical communication and feed-forward latency: remote CX/teleportation and RSI rely on measurement outcomes and classical signaling; the depth model ignores classical delays, control electronics constraints, and synchronization overhead, which could affect both depth and error.

- Validate the assumption of maximally parallel compute/storage modules: the architecture assumes full parallelism and all-to-all connectivity within modules; real devices have limited parallelism, crosstalk, restricted connectivity, and scheduling constraints that could erode the depth advantage.

- Reassess storage module assumptions: storage qubits are treated as “long-lived” with negligible idle noise, and large buffers (n_s=2n per QPU) are assumed; the sensitivity of results to realistic memory coherence, leakage, and storage footprint is not evaluated.

- Account for correlated, non-Markovian, and hardware-specific noise: the noise model is simple depolarizing noise with fixed ratios (remote gate noise set to 3p); it does not capture crosstalk, drift, leakage, biased noise, gate-duration-dependent errors, or link-induced correlations, which may alter the advantage.

- Compare resource footprints fairly: distributed CliNR uses many more total qubits across multiple QPUs (e.g., per QPU 2n+1 compute + 2n storage, versus 3n+1 monolithic); the paper does not analyze total qubit cost vs. performance, nor qubit-per-QPU constraints in near-term hardware.

- Optimize circuit partitioning and scheduling: the split into t equal-depth subcircuits and serial RSI is assumed; there is no algorithmic method to choose t, balance q_i and δ_i, minimize stalls, or exploit alternative schedules (e.g., overlapping RSIs, parallel injections, dynamic reorderings).

- Detail the RSV design and its trade-offs: r (number of stabilizer checks) is set (e.g., r=3 in simulations) but not optimized; the relationship between r, restart probability q_i, preparation depth δ_i, and logical error is not studied, nor is adaptive/stop-on-detection RSV analyzed.

- Clarify remote gate implementation costs: the paper assumes each remote CX consumes one Bell pair and assigns 3p error; remote entanglement-based gates can require extra operations, classical corrections, or additional Bell pairs depending on protocol—these costs are not detailed or varied.

- Evaluate scaling with larger t and alternative topologies: simulations use t=3 and a ring; the depth and error scaling for larger t, different topologies (line, star, mesh), and non-adjacent connectivity are not explored, especially under the one-Bell-pair-per-link restriction.

- Integrate entanglement generation queueing and buffering: the model allows pre-generation during RSP but does not present queueing policies, buffer sizing strategies, or stall analysis under variable τ_e and link contention, especially with heterogeneous link performance.

- Assess final teleportation overhead and alternatives: the model teleports the final state from Q_t to Q_0 without accounting for time and errors; evaluating whether to keep output on Q_t, pipeline across QPUs, or restructure post-processing could reduce overhead.

- Conduct robustness analyses across p, τ_e, r, and idle noise rates: the simulations fix p=10⁻⁴ and specific idle noise assumptions; the sensitivity of the advantage to these parameters and to realistic variability is not provided.

- Provide statistical rigor in simulation results: using 20 circuits × 200 samples yields means and standard deviations but no confidence intervals, finite-size effects analysis, or assessment of distribution tails (important for restart-heavy processes).

- Explore integration with fault-tolerant schemes: CliNR is a partial error mitigation approach; the paper does not discuss how distributed CliNR would interact with error-corrected QPUs, entanglement distillation within codes, or whether it can reduce logical error budgets in fault-tolerant stacks.

- Quantify and plan the proposed “distributed quantum superiority” experiment: resource counts (qubits per QPU, number of QPUs, τ_e, link fidelity), required depth and error budgets, classical hardness under realistic noise, and verification strategy are not specified.

- Develop practical hardware mappings: how to realize the compute/storage split, inter-module couplers, cross-talk mitigation, measurement/readout routing, and timing on specific platforms (ions, superconducting, NV centers) is left open.

- Analyze alternative CliNR variants hinted in Conclusions: two-sided RSP to halve depth and parallel instances (m) to reduce expected depth by ~1/m are proposed but not analyzed; their impact on qubit/memory overhead, entanglement demand, and noise is unknown.

Glossary

- Asymptotic regime: A limit in which system size or parameters grow, used to derive scaling results and requirements. "In the asymptotic regime, we relax assumption (2) and we prove that links producing Bell pairs in parallel, where is the number of QPUs, is sufficient to avoid stalling distributed CliNR, independently of the number of qubits per QPU."

- Bell pair: A maximally entangled two-qubit state used as a resource for nonlocal operations and teleportation. "each link produces only one Bell pair at a time"

- Bernoulli random variable: A random variable that takes value 1 with some probability and 0 otherwise. "Let be Bernoulli random variables such that ."

- Big-O notation: Asymptotic notation describing upper bounds on growth rates. "links producing Bell pairs in parallel"

- Circular topology: A network layout where each node connects to two neighbors, forming a ring. "we restrict ourselves to a circular topology for the QPU network"

- Circuit knitting: Techniques to replace inter-QPU quantum gates with classical post-processing and local operations. "Another insight comes from circuit knitting techniques"

- Circuit level noise model: A model applying noise channels after each operation in a circuit to capture realistic errors. "We use a circuit level noise model where each operation is followed by a depolarizing channel applied to the support of the operation."

- Clifford circuit: A quantum circuit composed of gates from the Clifford group, often amenable to efficient simulation and stabilizer methods. "In what follows, we consider three implementations of a -qubit Clifford circuit with size ."

- Clifford subcircuit: A portion of a circuit consisting only of Clifford operations, often processed or verified separately. "CliNR is a technique for reducing logical error rates in quantum circuits by performing Clifford subcircuits offline and using stabilizer measurements to check for errors."

- CliNR: A partial error correction scheme that prepares, verifies, and injects resource states to reduce noise in Clifford circuits. "We consider the CliNR scheme which is a partial error correction scheme designed to reduce the noise rate of Clifford circuits at the price of a smaller overhead than quantum error correction."

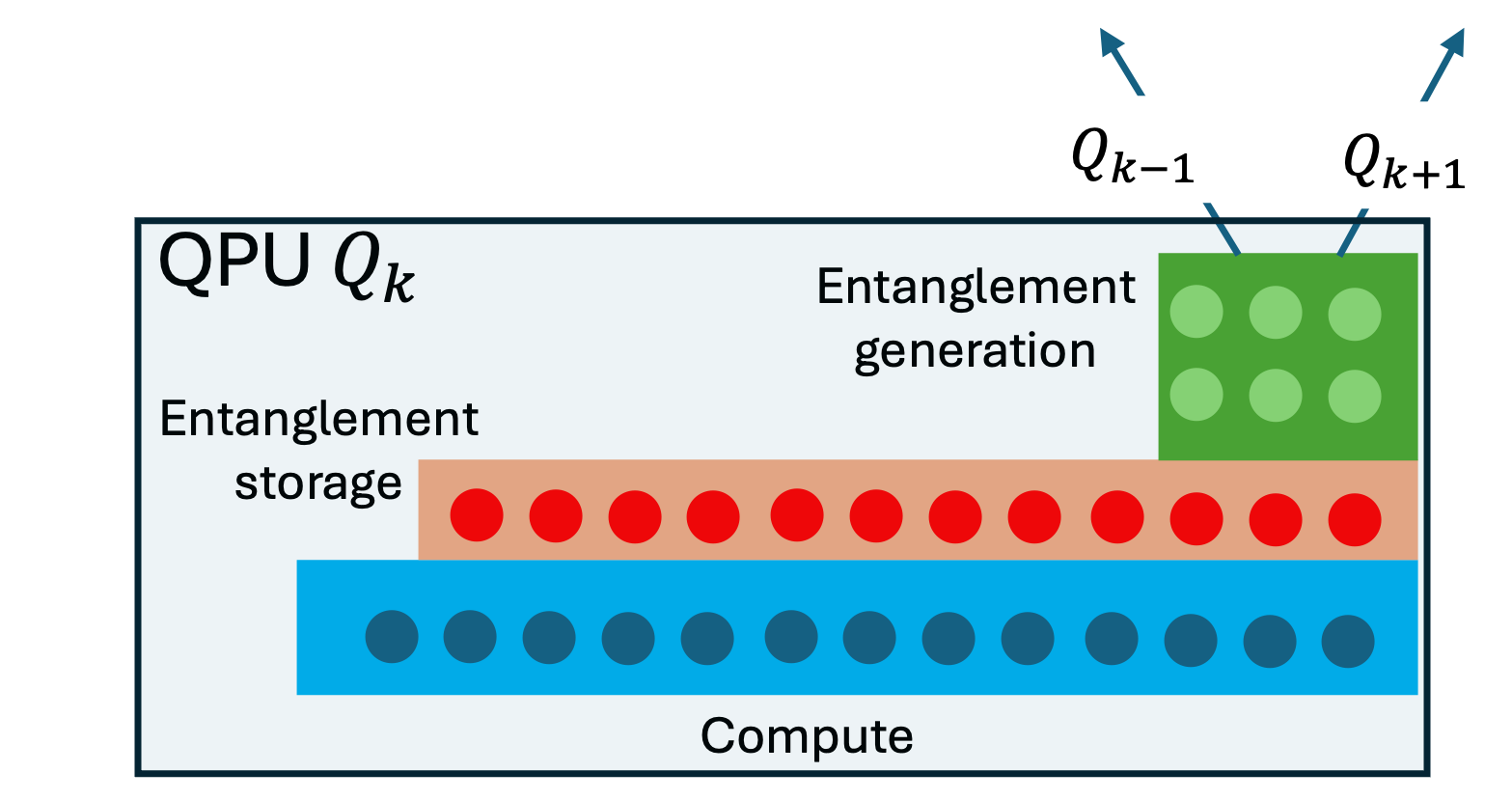

- Compute module: The part of a QPU where core quantum operations are performed on fully connected, parallel qubits. "The {\em compute module} has fully connected, maximally parallel qubits, and it is where the core of the computation takes place."

- Conjugated Clifford circuits: A structured class of circuits used in complexity-theoretic proposals for quantum advantage. "distributed quantum superiority experiment based on the conjugated Clifford circuits of Bouland, Fitzsimons and Koh implemented with distributed CliNR."

- Coupon collector problem: A classical probabilistic problem used here to bound the expected time for parallel successes. "The following lemma, which is a variant to the coupon collector problem, is used to establish an upper bound on the expected time for the parallel RSP in distributed CliNR."

- CX gate: The controlled-X (CNOT) two-qubit gate, a standard entangling operation. "two-qubit gates , and ,"

- CY gate: The controlled-Y two-qubit gate. "two-qubit gates , and ,"

- CZ gate: The controlled-Z two-qubit gate. "two-qubit gates , and ,"

- Depolarizing channel: A noise process that replaces the state with a maximally mixed state with some probability. "We use a circuit level noise model where each operation is followed by a depolarizing channel applied to the support of the operation."

- Distributed architecture: A quantum computing setup with multiple interconnected QPUs that share entanglement over links. "A {\em distributed architecture} includes multiple QPUs connected through links producing entanglement."

- Entanglement distillation: Protocols that improve the fidelity of entangled states by consuming multiple noisy pairs. "Moreover, the need for entanglement distillation might further increase the entanglement generation time"

- Entanglement generation module: A QPU subsystem responsible for creating inter-QPU Bell pairs. "The {\em entanglement generation module} is used to generate Bell pairs between connected QPUs."

- Entanglement generation time: The time required to create a Bell pair across a link, often slower than gate times. "the time to generate a Bell pair is times longer than the gate time."

- EPR pair: Another name for a Bell pair, representing a maximally entangled two-qubit state. "The storage qubits are used to store half of an EPR pair, the other half being stored in the storage module of a neighboring QPU."

- Gate time: The duration of a basic quantum gate operation on a QPU. "the time to generate a Bell pair is times longer than the gate time."

- Idle qubits: Qubits not undergoing operations during a circuit layer, which can accumulate decoherence. "Furthermore, idle qubits in the compute module experience a depolarizing channel with noise rate (per depth 1 layer)."

- Logical error rate: The probability that a computation yields an incorrect logical outcome after error mitigation or correction. "distributed CliNR can achieve simultaneously a lower logical error rate and a shorter depth than both the direct implementation and the monolithic CliNR implementation of random Clifford circuits."

- Monolithic architecture: A single-QPU device with fully connected qubits and maximal parallelism, without interconnect constraints. "The {\em monolithic architecture} describes a single QPU with fully connected and maximally parallel qubits."

- Pauli errors: Discrete error operators from the Pauli set (X, Y, Z) applied with some probability. "one of the 15 non-trivial Pauli errors with probability each."

- Pauli measurements: Measurements in the eigenbases of Pauli operators (X, Y, Z). "and single-qubit Pauli measurements,"

- Quantum interconnects: Technologies enabling entanglement generation between distinct QPUs. "Quantum interconnects generating entanglement between different QPUs have been demonstrated experimentally"

- Quantum processing unit (QPU): A hardware module that executes quantum gates and measurements on its qubits. "The main bottleneck for distributed quantum computing is the rate at which entanglement is produced between quantum processing units (QPUs)."

- Quantum superiority experiment: A task designed to demonstrate computational advantage over classical methods. "Moreover, we envision a distributed quantum superiority experiment based on the conjugated Clifford circuits of Bouland, Fitzsimons and Koh implemented with distributed CliNR."

- Remote gate: A gate enacted between qubits on different QPUs, typically consuming a shared Bell pair. "The storage qubits are used exclusively to implement a {\em remote gate}, that is, either a gate or teleportation, between qubits in the compute modules of two different QPUs."

- Resource state: A specially prepared multi-qubit state used to implement a target subcircuit via injection. "Preparation of a $2n$-qubit resource state ."

- Resource state injection (RSI): The step that consumes a verified resource state to apply the intended subcircuit to the data. "Resource state injection (RSI). If no errors are detected during RSV, the subcircuit is applied to the -qubit input state by consuming the verified resource state ."

- Resource state preparation (RSP): The process of creating the resource state, often involving Bell pairs and a subcircuit execution. "Resource state preparation (RSP). Preparation of a $2n$-qubit resource state ."

- Resource state verification (RSV): A series of stabilizer checks to detect errors before injection, restarting on failure. "Resource state verification (RSV). The resource state is verified using stabilizer measurements."

- Restart probability: The chance that verification detects an error, causing the preparation to restart. "Denote by the depth of the RSP for in the absence of restart and let be the restart probability for this subcircuit."

- Stabilizer measurements: Measurements of stabilizer operators used to detect errors in stabilizer-based schemes. "The resource state is verified using stabilizer measurements."

- Storage module: A QPU subsystem with long-lived qubits used to store halves of Bell pairs for remote operations. "Once a Bell pair is generated, we assume that it is stored in the {\em storage module}, which consists of storage qubits."

- Tail sum formula: A technique to compute expectations by summing probabilities of exceeding thresholds. "To bound the expectation of , we use the tail sum formula"

- Teleportation: A protocol that transfers quantum states using entanglement and classical communication. "{\bf Teleportation}. Teleport the -qubit state from to ."

- Union bound: A probabilistic inequality bounding the probability of a union of events by the sum of individual probabilities. "Therefore, a union bound yields"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are applications that can be piloted or deployed with existing prototype hardware and software stacks (e.g., trapped-ion or superconducting platforms with demonstrated interconnects, and today’s quantum compilers/runtimes).

- Industry — Hardware: Multi-QPU ring prototypes with slow interconnects

- Use case: Build and benchmark 3–5 QPU ring-topology systems where each QPU has a compute module (≈2n+1 qubits), a storage module (≈2n qubits), and an entanglement-generation module. Demonstrate lower depth and lower logical error rates on Clifford-heavy workloads using distributed CliNR.

- Tools/products/workflows: Modular QPUs; entanglement “state factories”; storage-memory arrays; remote CX/teleportation primitives; entanglement prefetching queues; control firmware for RSP/RSV/RSI orchestration.

- Sectors: Quantum hardware, telecom-photonics (interconnects).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Two links per QPU in a ring; one Bell pair at a time per link; entanglement generation time τ_e up to ≈5× gate time; long-lived storage qubits; remote gate error ≈3p with intra-QPU two-qubit error ≈p≈1e−4.

- Industry — Software/Cloud: Distributed CliNR compiler pass and runtime scheduler

- Use case: Implement a compiler transformation that partitions Clifford circuits into t subcircuits of balanced depth, schedules parallel RSP and RSV on different QPUs, and serial RSI with entanglement prefetching to minimize stalls.

- Tools/products/workflows: A “dist-CliNR” pass for Qiskit/Cirq/Tket; runtime entanglement manager (EPR buffer sizing, link allocation); error-aware scheduling; logics to restart RSV on failure; Stim-based simulation-backed validation.

- Sectors: Quantum software, cloud services.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable per-link τ_e calibration; remote CX API; measurement/classical-control latencies modeled; circuit segments predominantly Clifford.

- Industry — Benchmarking and SLAs for interconnects

- Use case: Introduce interconnect readiness benchmarks: (i) threshold τ_e below which distributed CliNR beats monolithic and direct circuits on depth and logical error; (ii) entanglement buffer occupancy and refill rates during RSI; (iii) observed speedup vs. number of subcircuits t.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Distributed Clifford Benchmark Suite” (random Clifford circuits sized n2); dashboards for τ_e, buffer occupancy, restart rates, achieved depth/error-rate.

- Sectors: Quantum hardware test/validation, vendor SLAs, cloud procurement.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to multi-QPU rigs; standardized noise reporting; reproducible Clifford workloads.

- Industry — Alternative to circuit knitting for moderate interconnects

- Use case: Replace circuit knitting (which scales poorly with number of remote gates) by distributed CliNR when τ_e is not extremely slow. Gain lower depth/error on Clifford-dominant workflows (stabilizer pre/post-processing in larger algorithms).

- Tools/products/workflows: Hybrid planner that selects between knitting and distributed CliNR based on predicted entanglement bottlenecks.

- Sectors: Software, hybrid quantum-classical solutions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Moderate interconnect quality; availability of storage qubits; Clifford-heavy segments identifiable by compiler.

- Academia — Near-term distributed “quantum advantage” demos

- Use case: Implement conjugated Clifford circuits of Bouland–Fitzsimons–Koh with distributed CliNR to target superiority/advantage in a multi-QPU setting under slow interconnects.

- Tools/products/workflows: Small-ring QPU experiments; fidelity boosters via CliNR’s verification; cross-lab reproducibility kits.

- Sectors: Academic research labs; cross-institution quantum network testbeds.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to 3–5 modules; τ_e/gate-time ≤ 5; careful noise calibration and verification; classical post-processing pipelines.

- Academia — Experimental validation of entanglement prefetching and RSI pipelining

- Use case: Show that preparing n Bell pairs per link during RSP/RSV avoids RSI stalls; quantify depth/error improvements and restart-rate distributions.

- Tools/products/workflows: Time-resolved link utilization traces; controlled RSP/RSV restarts; EPR buffer size sweeps.

- Sectors: Experimental quantum information science.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sufficient storage qubits; on-chip/out-of-chip memory with negligible idle noise; accurate τ_e monitoring.

- Policy — Procurement specifications for modular QC pilots

- Use case: Define minimum viable system requirements for funded multi-QPU demonstrators: ring topology, τ_e characterization, storage capacity (n_s≈2n), compiler/runtime support for distributed CliNR, benchmark reporting.

- Tools/products/workflows: RFP templates; standard reporting of τ_e, remote gate error multipliers, and distributed benchmark results.

- Sectors: Public funding agencies, standards bodies, national labs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Vendor willingness to disclose calibrated metrics; availability of interconnect modules.

- Policy — Early interoperability profiles for remote-gate interfaces

- Use case: Encourage a minimal API for remote CX/teleportation primitives and entanglement resource management across vendors, focused on ring-connected pilot networks.

- Tools/products/workflows: Draft interface specs; plugfests with small demos; test harnesses.

- Sectors: Standards, cross-vendor ecosystems.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Agreement on primitive definitions and error models; support for classical control latency constraints.

- Daily Life — Better user experience on quantum cloud platforms

- Use case: For users submitting Clifford-heavy circuits (e.g., stabilizer pre/post-processing), cloud providers can transparently route to multi-QPU backends with distributed CliNR for lower depth and error, improving job success and turnaround.

- Tools/products/workflows: Backend selection heuristics; job metadata indicating distributed execution; user-facing metrics on depth/fidelity gains.

- Sectors: Quantum cloud users in education and R&D.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cloud access to multi-QPU hardware; compiler/runtime integration; user consent for distributed execution.

Long-Term Applications

These require additional research, scaling, or maturation of interconnects, memories, control stacks, and standards.

- Industry — Scaling rule-of-thumb: O(T/ln T) parallel links per connection

- Use case: Architect next-gen systems where each neighboring QPU pair supports O(T/ln T) parallel entanglement channels to avoid stalling as the number of QPUs T grows (independent of qubits per QPU).

- Tools/products/workflows: Multi-core link modules; wavelength/polarization multiplexing; high-rate photon collection (cavities); memory-enhanced repeaters.

- Sectors: Quantum hardware, photonics, telecom infrastructure.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Relaxation of “one Bell pair at a time” constraint; stable multi-channel operation; scalable synchronization across T nodes.

- Industry — Productization of “resource state factories”

- Use case: Dedicated on-module factories that continually prepare and verify CliNR resource states during user idle periods, filling verified-state buffers to feed RSI on demand.

- Tools/products/workflows: Background RSV pipelines; quality-tracking of prepared states; inventory/expiry policies; integration with job schedulers.

- Sectors: Hardware systems, operating software for QPUs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-yield verification; low idle noise in storage; trusted discard-and-reprepare loops.

- Industry — Distributed execution for non-Clifford workloads via Clifford partitioning

- Use case: Embed distributed CliNR for the Clifford “skeleton” of hybrid circuits (e.g., variational algorithms, error-detection layers), with localized injection of non-Clifford gates (e.g., magic states) on fewer modules to reduce depth and error.

- Tools/products/workflows: Circuit partitioners that isolate Clifford layers; asynchronous subcircuit injection; hybrid resource orchestration.

- Sectors: Software for chemistry/materials optimization, error-mitigated simulation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear separation of Clifford vs. non-Clifford layers; robust magic-state pipelines; acceptable communication latency.

- Industry — Data-center scale quantum clusters

- Use case: Assemble racks of modular QPUs in rings/meshes, with inter-rack photonic links, providing a “quantum cluster” abstraction to users for large Clifford-dominant workloads and multi-tenant isolation.

- Tools/products/workflows: Cluster OS for QPUs; entanglement routing; QoS for links; monitoring/telemetry of τ_e and buffer health; elastic scaling of subcircuits t.

- Sectors: Cloud/enterprise computing, hyperscalers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust optical networking; standardized link-layer protocols; fault detection and recovery procedures.

- Academia — Theoretical extensions of partial error correction beyond CliNR

- Use case: Generalize partial error-correction schemes to non-Clifford families and to heterogeneous architectures, exploring trade-offs between verification depth, restart rates, and interconnect demands.

- Tools/products/workflows: New verification codes; stochastic models of restarts; asymptotic analyses across topologies beyond rings.

- Sectors: Quantum information theory, algorithms.

- Assumptions/dependencies: New bounds for mixed Clifford/non-Clifford structures; realistic noise/interconnect models.

- Academia — Large-scale distributed superiority/advantage experiments

- Use case: Execute larger conjugated Clifford or stabilizer-heavy random circuit families over tens of modules, exploiting O(T/ln T) link scaling to avoid stalls and to push classical intractability.

- Tools/products/workflows: Cross-facility federation; joint calibration protocols; public result verification datasets.

- Sectors: Multi-institution collaborations; national quantum initiatives.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Interoperable stacks; synchronized timing across sites; reproducible metrics.

- Policy — Interconnect performance standards and certifications

- Use case: Define test suites and certification levels for τ_e/gate-time ratios, remote gate fidelity penalties (e.g., 3p vs. p), Bell-pair throughput and quality with/without distillation, and memory-idle error rates.

- Tools/products/workflows: Compliance test harnesses; certification tiers; public scorecards for procurement.

- Sectors: Standards bodies, regulators, public buyers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community consensus on metrics; transparent vendor reporting.

- Policy — Investment prioritization for quantum networking R&D

- Use case: Inform funding priorities for memory-enhanced links, cavity-assisted collection, high-fidelity heralded schemes, and multi-channel (O(T/ln T)) link modules, tied to explicit application benchmarks like distributed CliNR.

- Tools/products/workflows: Roadmaps linking component metrics to system-level advantage; milestone-based funding tied to benchmark gains.

- Sectors: Funding agencies, public–private partnerships.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Technological feasibility of proposed link improvements; clear validation protocols.

- Daily Life — More reliable quantum cloud services for education and SMEs

- Use case: As clusters mature, end-users benefit from increased job reliability for verified Clifford segments inside larger workflows (e.g., teaching labs, small research groups).

- Tools/products/workflows: “Reliability tiers” for jobs that opt into distributed execution; credits/refunds tied to verification outcomes; pedagogical toolkits demonstrating distributed entanglement.

- Sectors: Education, SMB research users.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Affordable access to modular backends; simplified APIs; clear user documentation.

- Cross-cutting — Toolchain ecosystems and open tooling

- Use case: Open-source packages implementing partitioning, distributed CliNR scheduling, EPR buffering, and measurement-driven restarts; reference implementations for Stim-based validation and hardware backends.

- Tools/products/workflows: Libraries (e.g., “dist-clinr”), compilers passes, runtime plugins; CI pipelines with synthetic and real-hardware tests.

- Sectors: Open-source community, startups, academia.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Maintainers; permissive IP posture; cooperation from hardware vendors.

- Cross-cutting — Operational analytics and “entanglement observability”

- Use case: Production-grade observability for entanglement generation/consumption (buffers, latencies, failure modes) to diagnose stalls and tune τ_e targets and storage sizing.

- Tools/products/workflows: Telemetry agents on link modules; anomaly detection on restart rates; A/B tests of prefetch policies.

- Sectors: DevOps for quantum systems, reliability engineering.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Low-overhead monitoring; stable identifiers for EPR pairs; privacy/security of telemetry.

- Cross-cutting — Risk management and cost modeling

- Use case: TCO models weighing added hardware (storage, link multiplexing) vs. gains in depth/error; SLAs framed around τ_e thresholds where distributed CliNR dominates monolithic/direct baselines.

- Tools/products/workflows: Financial models; design space exploration tools; SLA contract templates.

- Sectors: Vendors, cloud providers, enterprise buyers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate cost curves for link modules/memory; validated performance envelopes across workloads.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.