Closing the Train-Test Gap in World Models for Gradient-Based Planning (2512.09929v1)

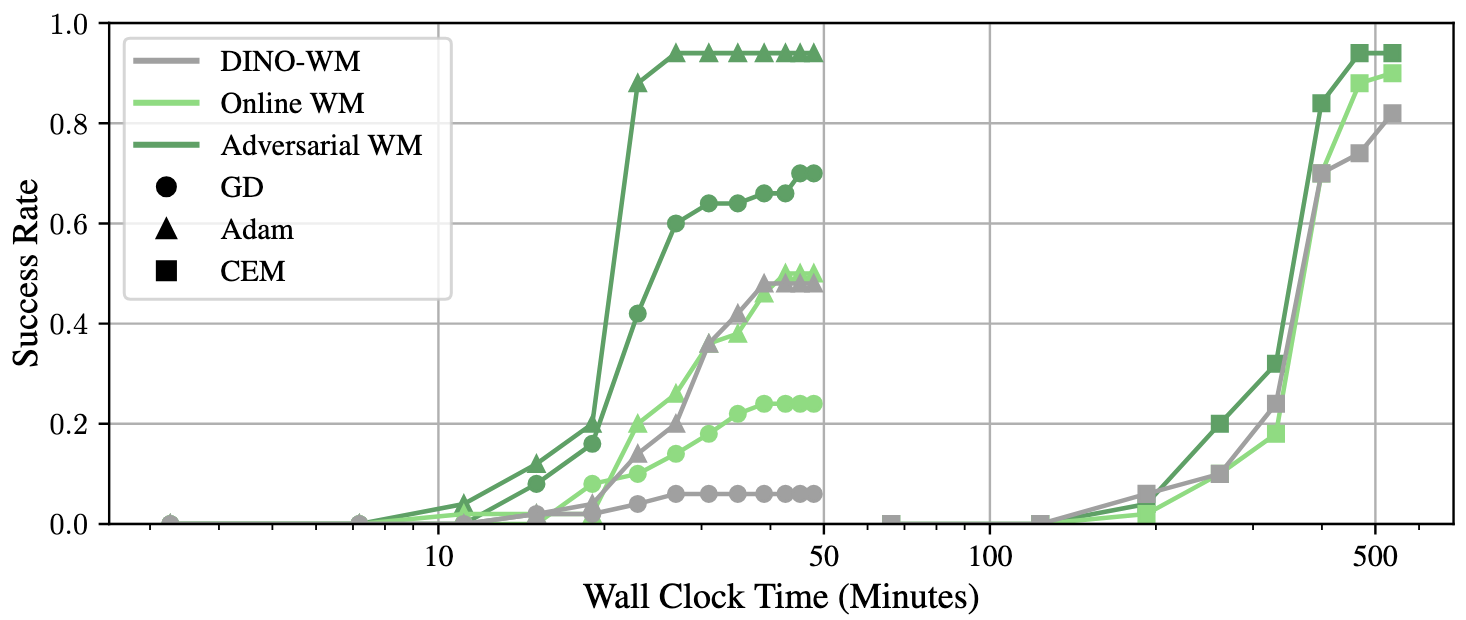

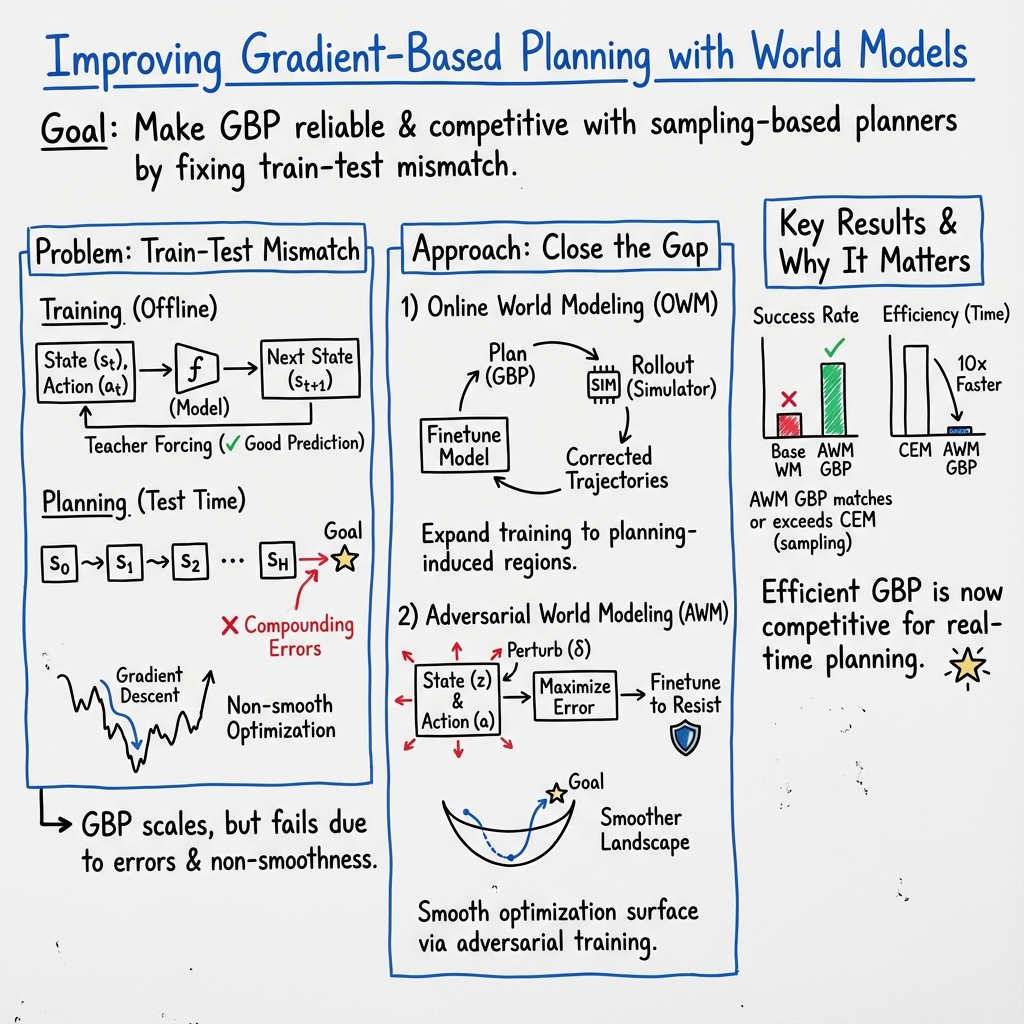

Abstract: World models paired with model predictive control (MPC) can be trained offline on large-scale datasets of expert trajectories and enable generalization to a wide range of planning tasks at inference time. Compared to traditional MPC procedures, which rely on slow search algorithms or on iteratively solving optimization problems exactly, gradient-based planning offers a computationally efficient alternative. However, the performance of gradient-based planning has thus far lagged behind that of other approaches. In this paper, we propose improved methods for training world models that enable efficient gradient-based planning. We begin with the observation that although a world model is trained on a next-state prediction objective, it is used at test-time to instead estimate a sequence of actions. The goal of our work is to close this train-test gap. To that end, we propose train-time data synthesis techniques that enable significantly improved gradient-based planning with existing world models. At test time, our approach outperforms or matches the classical gradient-free cross-entropy method (CEM) across a variety of object manipulation and navigation tasks in 10% of the time budget.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper tries to make robots plan their actions faster and more reliably by improving how “world models” are trained. A world model is like a learned simulator: it predicts what will happen next when a robot takes an action. The authors focus on a planning style called gradient-based planning, which uses calculus to directly adjust a sequence of actions to reach a goal. Their main goal is to close a “train–test gap” so the world model works well both during training and when used for planning in new situations.

What questions are the researchers asking?

In simple terms, the paper asks:

- Why does gradient-based planning often perform worse than other methods, even though it should be faster?

- Can we train world models in a smarter way so gradient-based planning becomes both accurate and stable?

- How can we make the model handle action sequences it didn’t see during training?

- Can we make the “optimization landscape” (the surface the planner climbs down to reach a goal) smoother and easier to navigate?

They suspect two big problems:

- During planning, the model gets pushed into weird situations it never saw during training, so its predictions become unreliable.

- The model’s “loss landscape” is bumpy and full of bad local minima, so gradients don’t guide the planner well.

How did they approach the problem?

The paper uses world models trained on expert examples (like videos and actions from skilled robots). Then, instead of only training to predict the next state, the authors add special training steps to make the model behave better when used for planning.

To understand some terms:

- World model: a learned “what happens next?” predictor.

- Gradient-based planning: a way to tweak actions using gradients (like following the slope downhill to minimize the distance to a goal).

- MPC (Model Predictive Control): plan a short action sequence, do the first few actions, then replan—repeat until you reach the goal.

- Latent space: a compact feature space where images are turned into useful numbers by an encoder, making prediction easier.

- Adversarial example: a tiny, carefully chosen change to inputs that makes a model mess up—useful for stress-testing and training robustness.

The paper offers two training improvements:

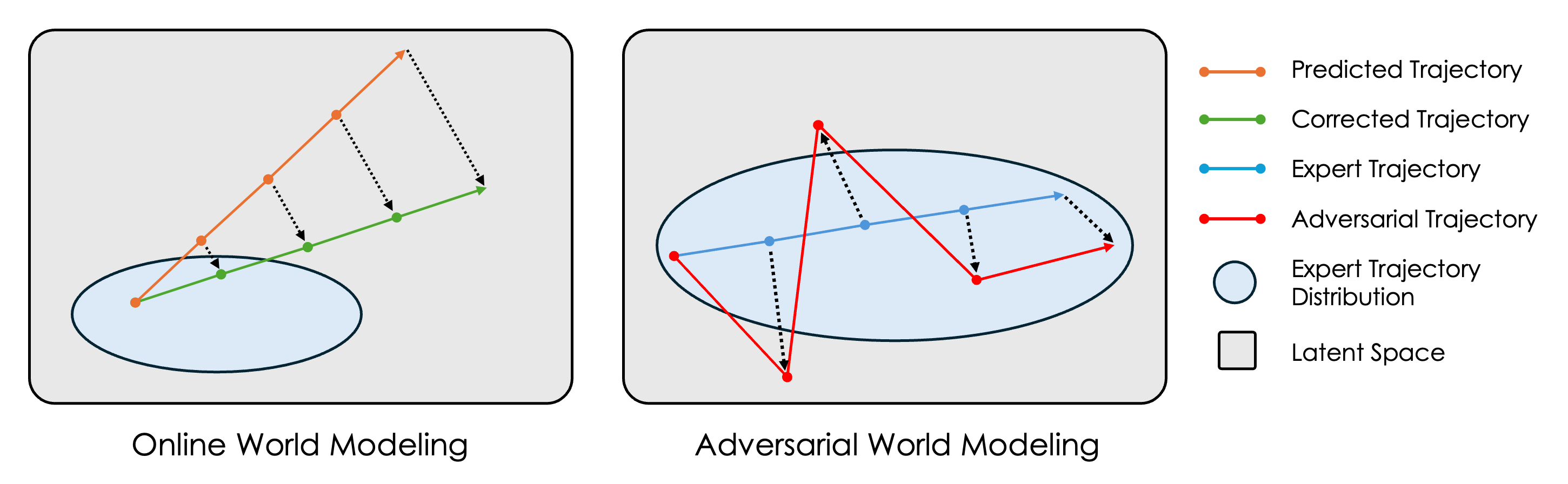

- Online World Modeling:

- Think of this like doing practice runs with a coach.

- The planner proposes a sequence of actions to reach a goal. A trusted simulator (the “coach”) shows what would really happen.

- The authors add these corrected “what actually happens” trajectories back into the training set.

- This expands the model’s experience beyond expert demonstrations to include the kinds of states the planner will actually visit.

- Adversarial World Modeling:

- Think of this like strength training with tricky drills.

- The authors slightly and cleverly change the inputs (states and actions) to find cases that make the model predict poorly.

- Then they train the model on these hard cases, so it becomes robust and its gradients are smoother.

- This reduces bumps in the loss landscape, helping gradients guide planning more reliably.

- They use a fast method (FGSM) to generate these small, worst-case tweaks efficiently.

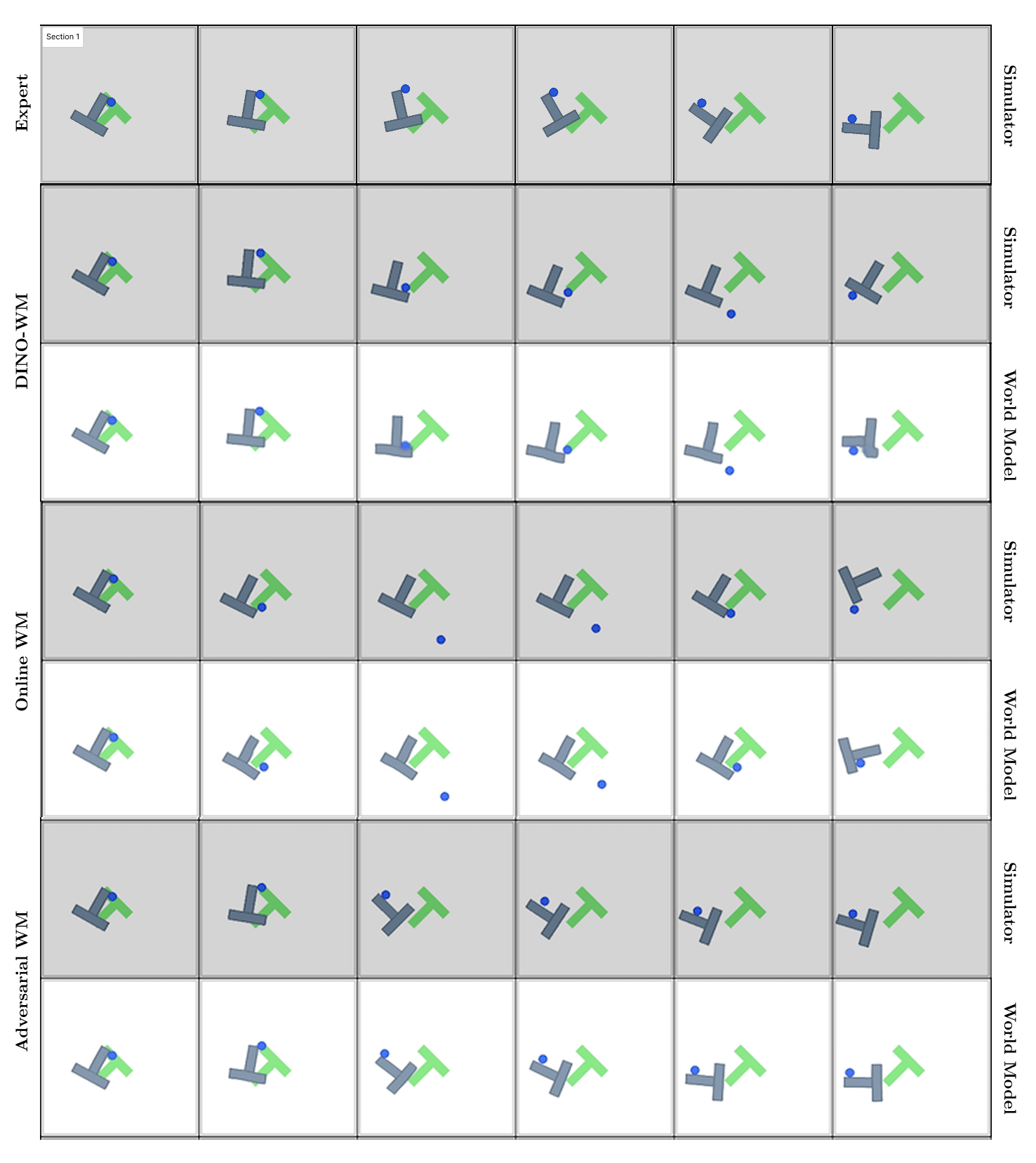

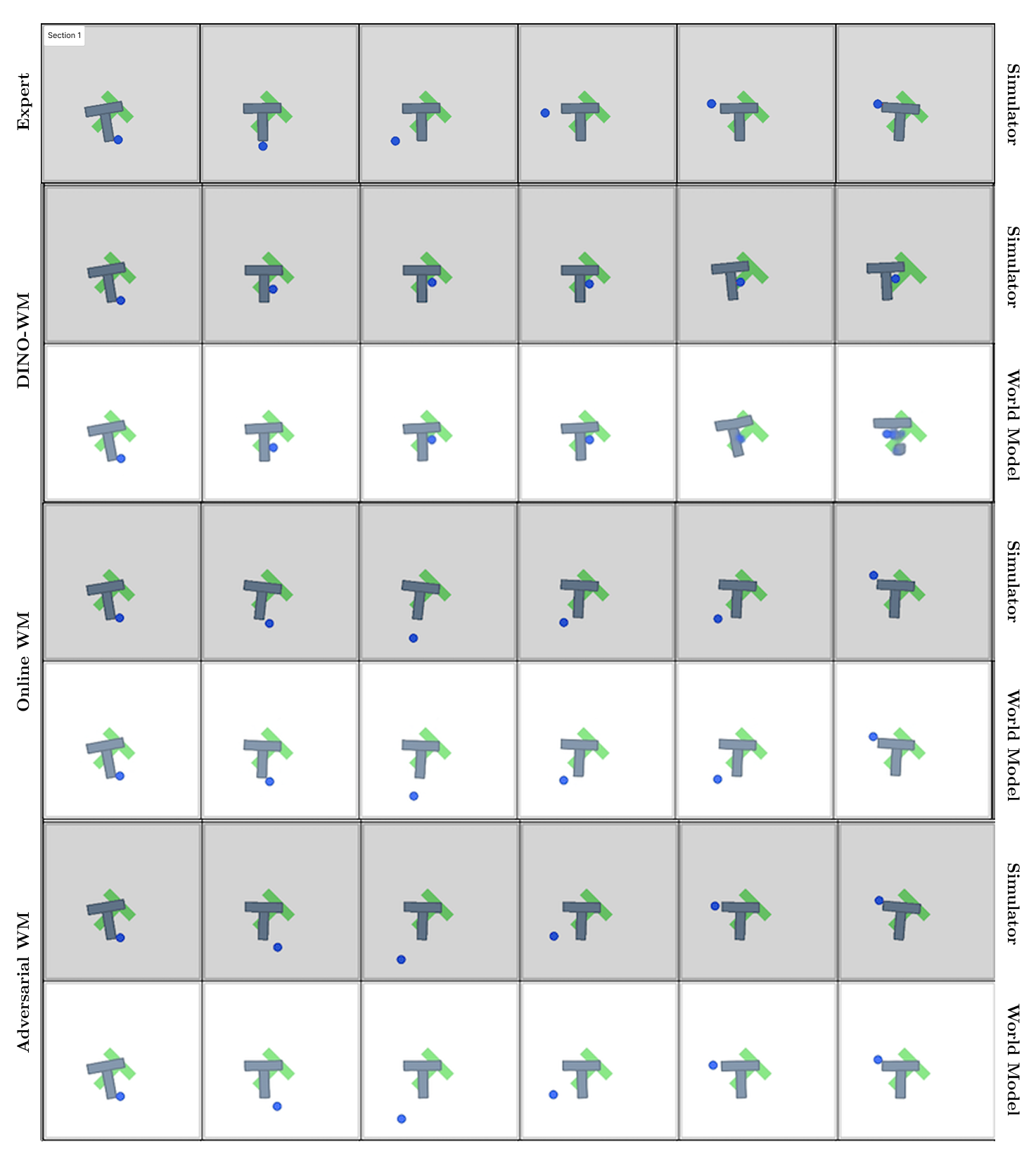

They still use the usual pipeline: encode images into a latent space using a strong, pre-trained vision model (DINOv2), then predict next latent states with a transformer-style network. Planning is done by backpropagating gradients through the world model to adjust action sequences, optionally with MPC to replan frequently.

What did they find and why does it matter?

Main findings:

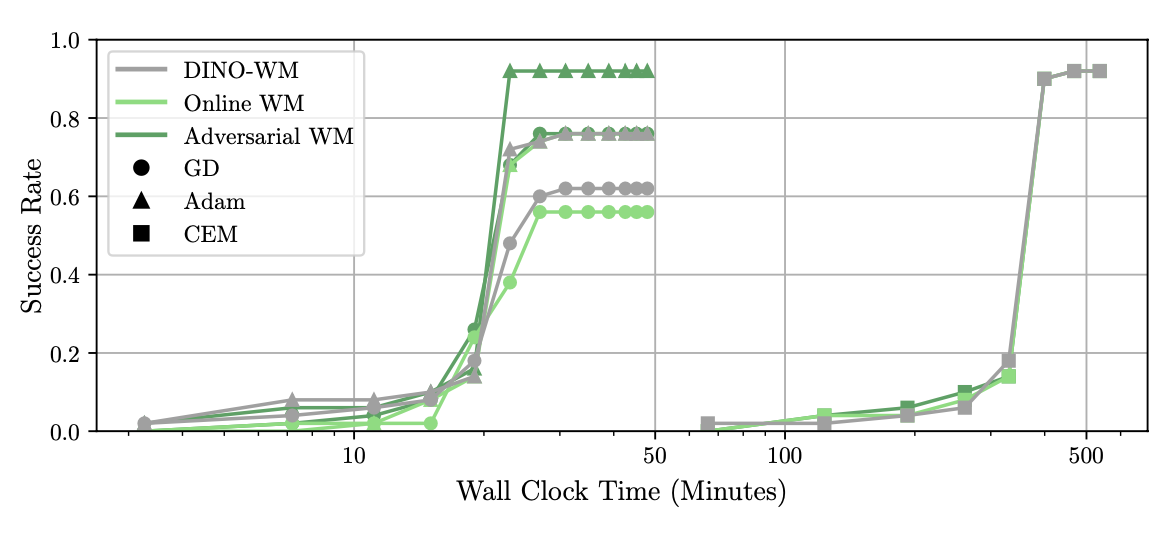

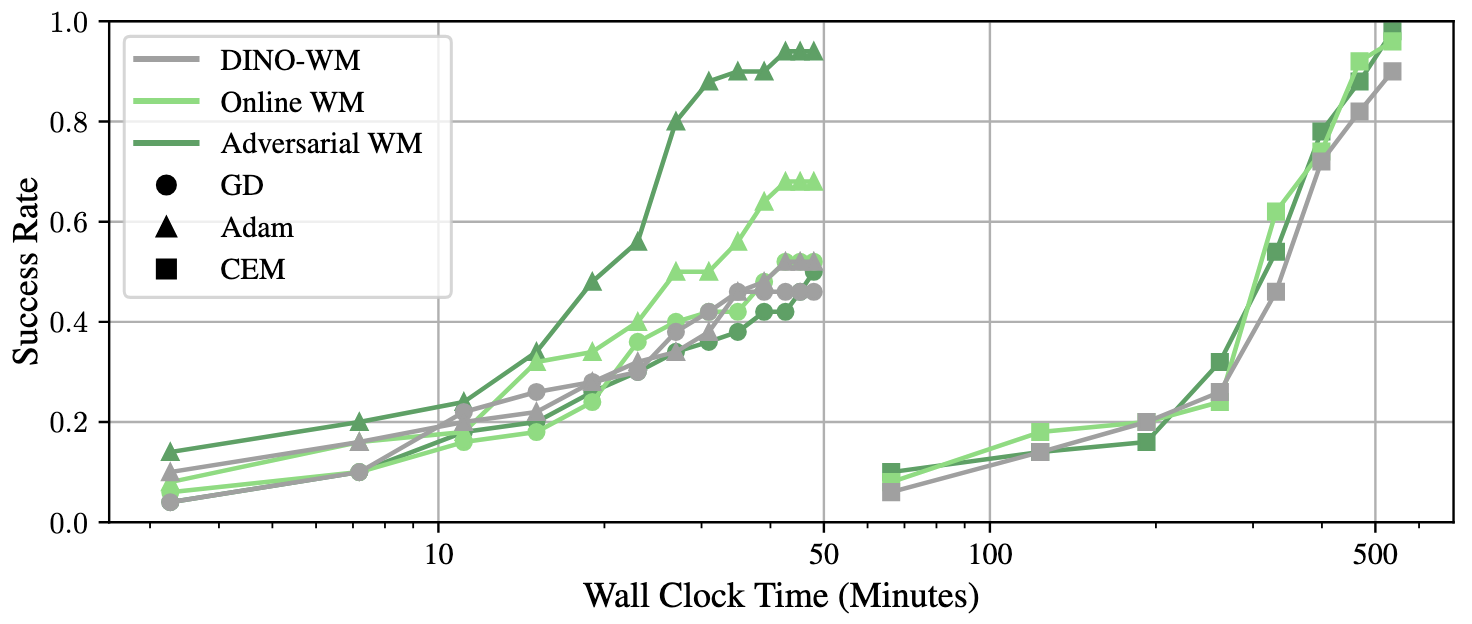

- With their improved training, gradient-based planning often matches or beats a popular search-based method called CEM (Cross-Entropy Method), while using only about 10% of the computation time.

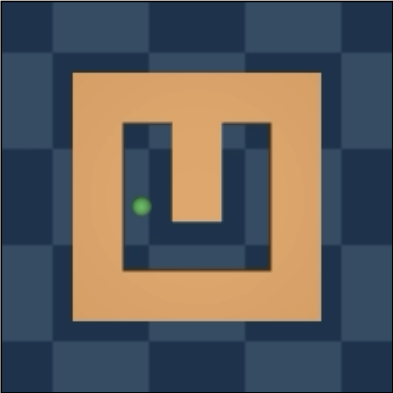

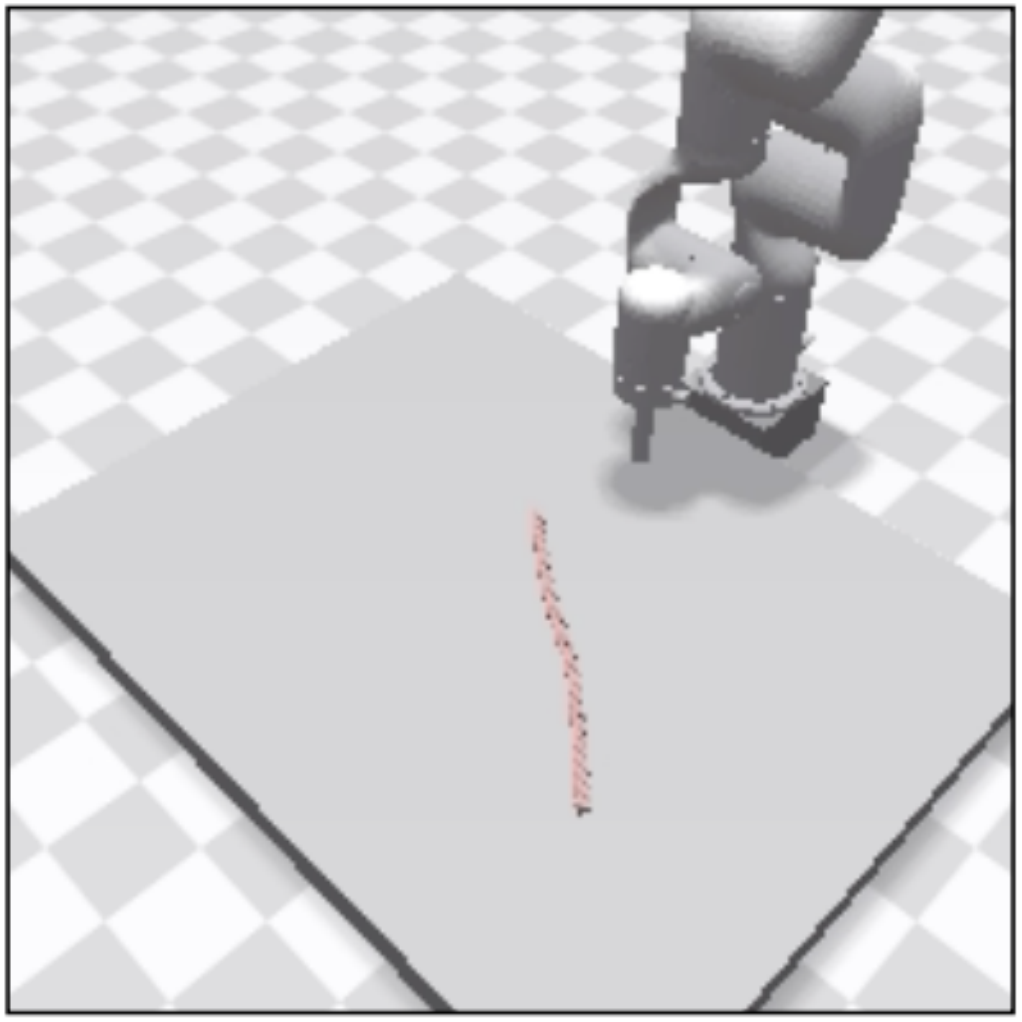

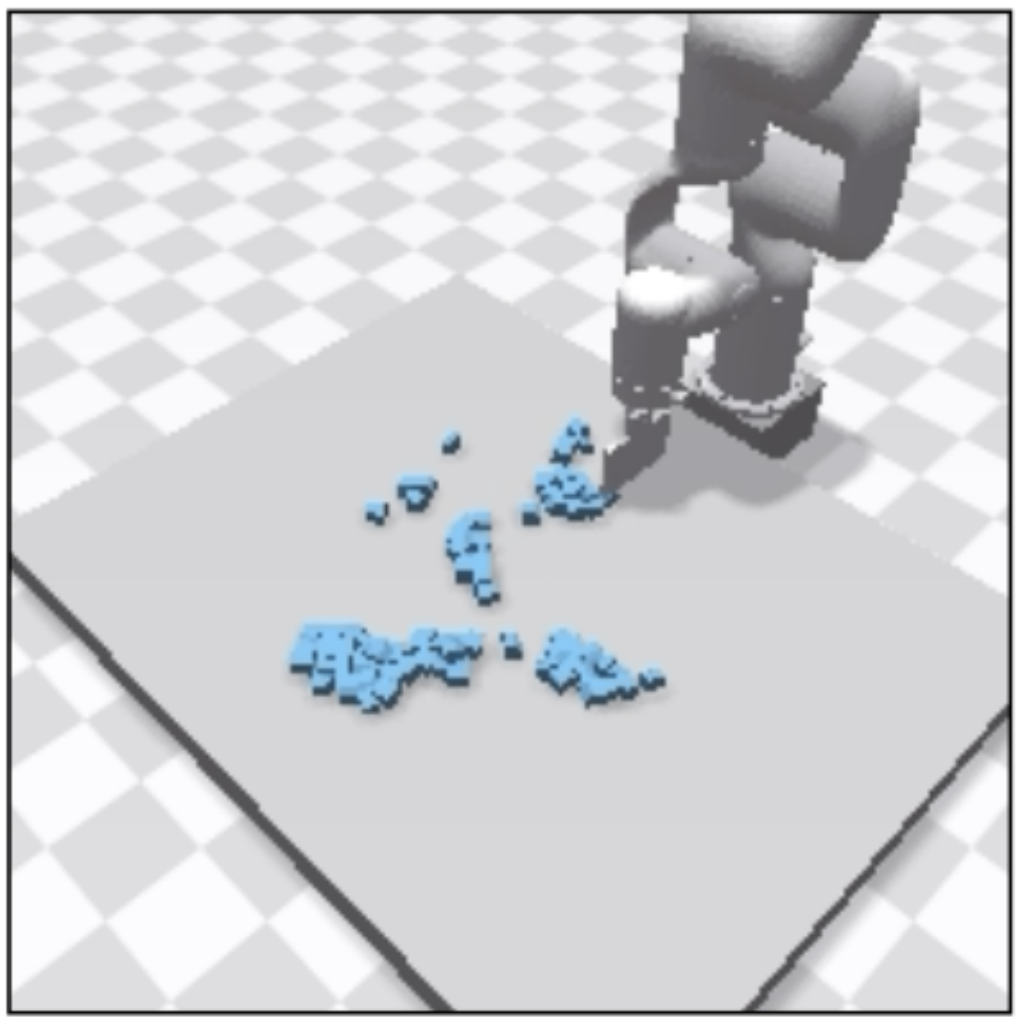

- They tested on three robotics-like tasks (PushT, PointMaze, Wall) and saw higher success rates, especially when using MPC.

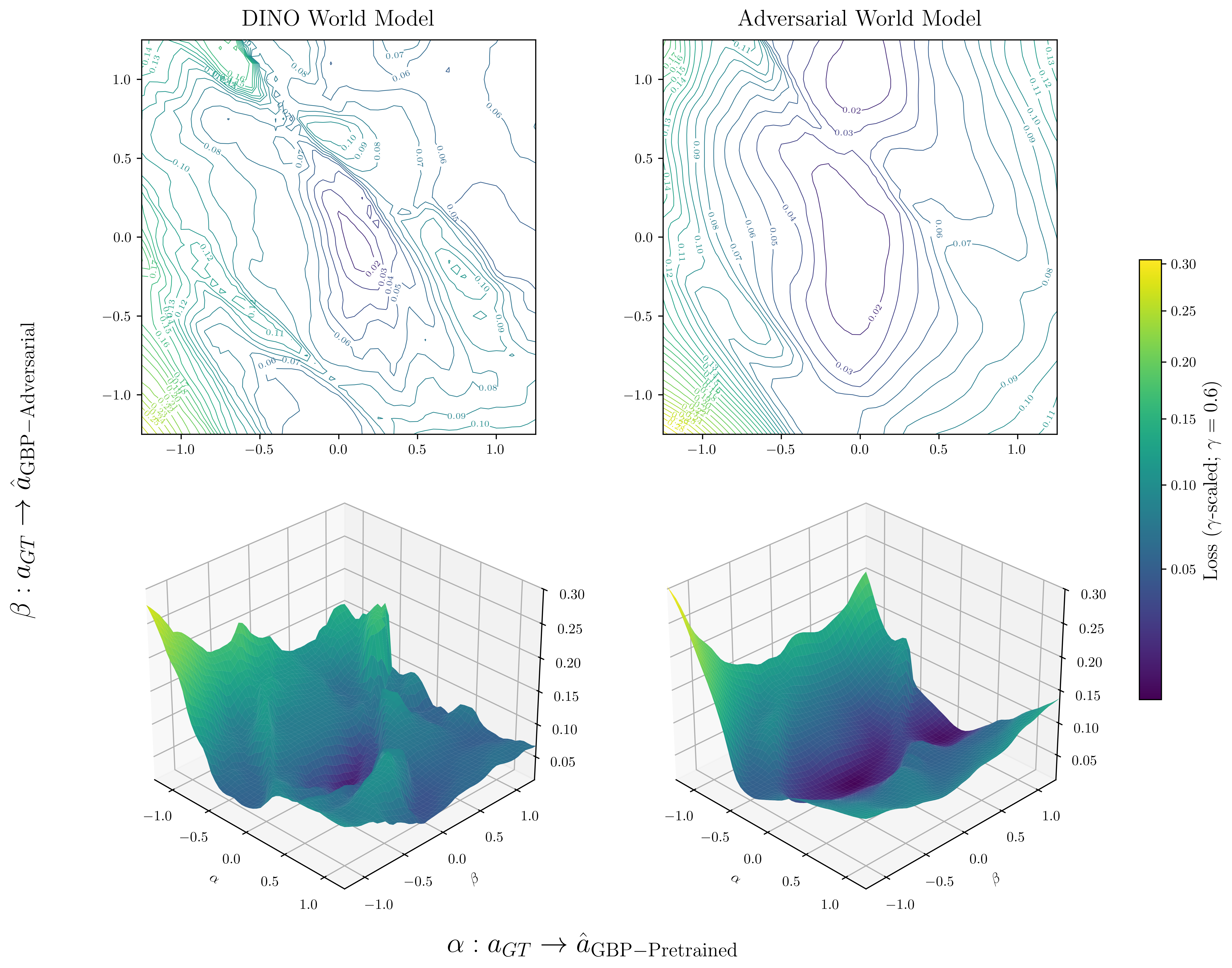

- Adversarial World Modeling made the optimization landscape smoother (fewer traps and flat spots), so gradient steps worked better.

- They measured the “train–test gap”: before, the model predicted well on expert data but worse on planning-generated data. After their training, this gap shrank—the model stayed reliable when actually used for planning.

- Overall, gradient-based planning became practical and competitive, not just theoretically appealing.

Why it matters:

- Faster planning means robots can react and plan in real time, which is crucial outside the lab.

- Robustness to unfamiliar states and small input changes makes planning safer and more dependable.

- This can reduce the need for slow, sampling-heavy methods and make learned models more useful in high-dimensional, image-based settings.

What’s the big picture and future impact?

This work suggests a simple but powerful idea: train your world model not just to predict the next step on clean expert data, but also on the kinds of tricky situations and off-distribution states it will face during planning. Doing so makes gradient-based planning both fast and reliable.

Potential impacts:

- More responsive robots for manipulation and navigation tasks.

- Better long-horizon planning using learned models (helpful where reinforcement learning can be slow or data-hungry).

- Practical planning in settings with limited compute or tight time budgets.

Future directions include testing these methods on real robots, handling noisy and unpredictable environments, and combining them with multi-level or hierarchical models to handle very long-horizon tasks even more effectively.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to be directly actionable for future research.

- Real-world validation: No experiments on physical robots; it remains unclear whether Online World Modeling (OWM) and Adversarial World Modeling (AWM) transfer under sensor noise, latency, actuation limits, and safety constraints.

- Reliance on a ground-truth simulator for OWM: OWM assumes access to an accurate dynamics simulator to “correct” planner-induced trajectories; how to obtain corrections in the absence of a simulator or under partial observability in real environments remains unresolved.

- Safety and feasibility constraints: Planning optimizes latent goal distance without explicit handling of safety, collisions, torque/velocity limits, or nonholonomic constraints; methods to integrate constraints into GBP with world models are not addressed.

- Latent metric validity: The use of an L2 distance in DINOv2 latent space as the planning objective is assumed but not validated; it is unknown when Euclidean distances in pretrained latent spaces correlate with task success or with physical closeness in state space.

- Encoder choice and adaptation: The encoder is frozen (DINOv2) and not jointly trained or adapted to planning; sensitivity to encoder choice (e.g., MAE, SimCLR, JEPA variants) and potential benefits of end-to-end finetuning are untested.

- Generalization breadth: Evaluation is limited to PushT, PointMaze, Wall (and brief mention of two manipulation tasks); scalability and robustness on contact-rich, high-dimensional, long-horizon, visually diverse, or stochastic domains are not demonstrated.

- Robustness to stochastic dynamics: The approach assumes deterministic dynamics; how AWM/OWM perform when dynamics or observations are stochastic (e.g., varying friction, wind, sensor noise) remains unknown.

- Theoretical guarantees: The paper argues that AWM “smooths” the action-level loss landscape empirically, but provides no formal analysis (e.g., Lipschitz bounds on input gradients, curvature control, or convergence guarantees for GBP).

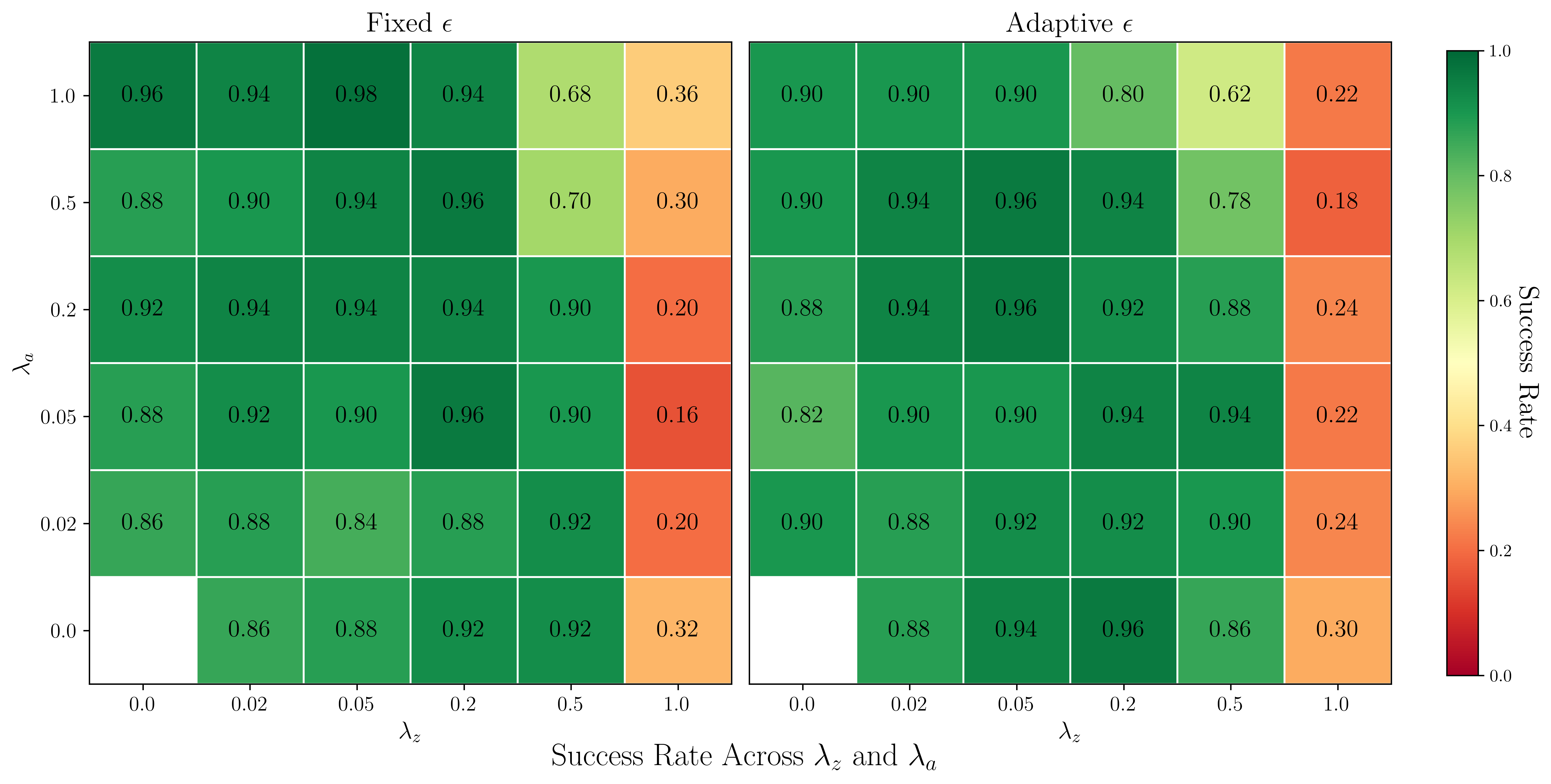

- Hyperparameter sensitivity: Despite reporting ranges for λ and ε, systematic sensitivity analyses across tasks and models (e.g., perturbation norms, step sizes, number of adversarial steps, minibatch composition) are missing.

- Strength of adversarial training: AWM primarily uses single-step FGSM-style perturbations; the effect of multi-step PGD, diverse norms (L2, L1), and mixed perturbation schedules on GBP stability and performance is not thoroughly investigated.

- Physical plausibility of perturbations: Perturbations are applied in latent state and action spaces with L∞ bounds but without constraints enforcing physical plausibility; how to ensure that adversarially perturbed samples reflect realizable states and valid control inputs is not addressed.

- Multi-step training objectives: Training uses one-step teacher forcing; whether multi-step prediction losses or rollout-based objectives reduce compounding errors and further improve GBP is not studied.

- MPC design choices: Sensitivity to MPC horizon H, execution window K, and replanning frequency is not analyzed; guidelines for stable GBP under different MPC configurations are absent.

- Optimization strategy breadth: Gradient-based planning explores GD and Adam only; second-order methods, L-BFGS, trust-region approaches, line-search strategies, restarts, and hybrid search-gradient planners are not compared.

- Initialization strategies: Random initialization often outperforms an “initialization network,” but alternative initializers (e.g., retrieval from nearest neighbors, diffusion-based priors, warm-start from CEM) and their impact on GBP remain unexplored.

- Model uncertainty: The approach does not model or leverage predictive uncertainty (e.g., ensembles, Bayesian models) to avoid adversarial action sequences or guide robust planning.

- Training compute vs inference gains: While GBP offers ~10× faster inference than CEM, the added training/finetuning costs (AWM/OWM) are not quantified; the amortization of training cost over deployments and tasks is unclear.

- Data requirements and sample efficiency: Dependence on large offline expert datasets is assumed; performance under limited data, suboptimal demonstrations, or noisy labels has not been characterized.

- Interaction with search-based planners: The impact of OWM/AWM on CEM performance is underexplored; whether finetuned models improve or degrade gradient-free planning is unclear.

- Loss landscape diagnostics: Beyond a single visualization, comprehensive diagnostics of the action-space landscape (e.g., curvature, gradient norms, basin sizes) pre- and post-finetuning are lacking.

- Combined OWM+AWM: The methods are presented separately; whether combining dataset aggregation (OWM) with adversarial training (AWM) yields additive or conflicting effects is not evaluated.

- Task-conditioned objectives: The weighted goal loss assumes intermediate states provide useful gradients; conditions under which this assumption holds (e.g., subgoal structure vs deceptive gradients) are not established.

- Transfer and multitask learning: It is unclear whether world models finetuned via AWM/OWM on one task transfer to new tasks or support multitask planning without catastrophic forgetting.

- Domain shift in perception: Robustness to changes in camera pose, lighting, textures, and backgrounds is not studied; adaptation strategies for perception shift are missing.

- Validity of latent perturbations: Perturbing latent states may induce semantically implausible observation changes; methods to constrain perturbations to a learned manifold or decoder-consistent region are not considered.

- Alternative regularization: Comparisons against other smoothing techniques (e.g., Jacobian/gradient penalties, spectral normalization, Lipschitz constraints, consistency regularization) are absent.

- Multi-step adversarial sequences: AWM attacks individual one-step transitions; whether adversarially perturbing entire sequences (trajectory-level attacks) better aligns training with planning is an open question.

- Evaluation metrics: Success rate is the primary metric; analyses of path efficiency, energy use, constraint violations, safety incidents, and recovery behavior are missing.

- Reproducibility and variance: Discrepancies in reported Wall results indicate variance; systematic reporting of seeds, confidence intervals, and failure mode analyses is needed.

- Goal specification and ambiguity: The approach assumes a single target image/latent; handling multi-modal goals, partial goals, or ambiguous goal states (e.g., equivalent configurations) is not addressed.

- Architecture choices: The transition model uses ViT; comparisons to structured dynamics models (e.g., recurrent, graph-based, physics-informed) and their interaction with GBP are not provided.

Glossary

- Adam: A first-order adaptive optimization algorithm commonly used for training neural networks. "We additionally evaluate using the Adam optimizer~\citep{Kingma2014AdamAM} during GBP."

- Adversarial examples: Inputs deliberately perturbed to maximize a model’s error, used to evaluate or improve robustness. "An adversarial example is generated by applying a perturbation to an input that maximally increases the model's loss."

- Adversarial inputs: Inputs produced by optimization that exploit model weaknesses, causing large errors. "Optimizing through learned models under such conditions is known to induce adversarial inputs \citep{szegedy2013intriguing, goodfellow2014explaining}."

- Adversarial training: A training strategy that optimizes model performance under worst-case perturbations to improve robustness. "Adversarial training improves model robustness by optimizing performance under worst-case perturbations \citep{madry2019deeplearningmodelsresistant}."

- Adversarial World Modeling: A finetuning approach that perturbs states and actions to smooth the planning loss landscape and improve gradient-based planning. "Adversarial World Modeling finetunes a world model on perturbations of actions and expert trajectories, promoting robustness and smoothing the world model's input gradients."

- Cross Entropy Method (CEM): A gradient-free, sampling-based optimization method often used in model-based planning. "At test time, our approach outperforms or matches the classical gradient-free cross-entropy method (CEM) across a variety of object manipulation and navigation tasks in 10\% of the time budget."

- Dataset Aggregation (DAgger): An online imitation learning technique that iteratively adds expert-labeled data from the learner’s rollouts. "This procedure is reminiscent of DAgger (Dataset Aggregation) \citep{ross2011reduction}, an online imitation learning method wherein a base policy network is iteratively trained on its own rollouts with the action predictions replaced by those from an expert policy."

- Differential Dynamic Programming (DDP): A second-order optimal control method that iteratively solves local approximations of dynamics. "Traditional methods such as DDP \citep{mayne1966second} and iLQR \citep{li2004iterative} rely on iteratively solving exact optimization problems derived from linear and quadratic approximations of the dynamics around a nominal trajectory."

- DINO-WM: A latent world model built on DINOv2 features used as the baseline in experiments. "We use DINO-WM \citep{zhou2025dinowmworldmodelspretrained} as our initial world model for its strong performance with CEM across our chosen tasks."

- DINOv2: A pre-trained visual representation model used as the encoder for latent states. "The embedding function is taken to be the pre-trained DINOv2 encoder ~\citep{oquab2024dinov2learningrobustvisual}, and remains frozen while finetuning the transition model ."

- Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM): A single-step adversarial attack that perturbs inputs in the direction of the gradient sign to maximize loss. "We generate adversarial latent states using the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) \citep{goodfellow2014explaining}, which efficiently approximates the worst-case perturbations that maximize prediction error \citep{fastbetterthanfree}."

- Gradient-based planning (GBP): Planning by directly optimizing action sequences through gradients of a differentiable world model. "We show that finetuning world models with these algorithms leads to substantial improvements in the performance of gradient-based planning (GBP)."

- iLQR (iterative Linear Quadratic Regulator): An iterative optimal control algorithm using local linear-quadratic approximations. "Traditional methods such as DDP \citep{mayne1966second} and iLQR \citep{li2004iterative} rely on iteratively solving exact optimization problems derived from linear and quadratic approximations of the dynamics around a nominal trajectory."

- IRIS: A transformer-based world model architecture used to validate method generality. "To validate the broad applicability of our approach, we also study the use of the IRIS \citep{micheli2023transformerssampleefficientworldmodels} world model architecture in \Cref{sec:diff-wm}."

- Joint-Embedding Prediction Architectures (JEPAs): Models that learn prediction objectives directly in latent space rather than reconstructing pixel observations. "such as those in joint-embedding prediction architectures (JEPAs)~\citep{lecun2022path, Bardes2024RevisitingFPA, Drozdov2024VideoRLA, Guan2024WorldMFA, zhou2025dinowmworldmodelspretrained}."

- Latent space: A lower-dimensional representation space where high-dimensional observations are embedded for efficient modeling. "an embedding function is employed to map observations to a lower-dimensional latent space ."

- Latent world model: A dynamics model that predicts transitions directly in latent space given current latent state and action. "our goal is to learn a latent world model "

- Loss landscape: The surface defined by the planning or training objective over inputs or parameters, affecting optimization difficulty. "Additionally, we empirically demonstrate that Adversarial World Modeling smooths the planning loss landscape"

- Model Predictive Control (MPC): A control strategy that repeatedly optimizes a finite-horizon action sequence and executes only a prefix before replanning. "World models paired with model predictive control (MPC) can be trained offline on large-scale datasets of expert trajectories"

- Model Predictive Path Integral control (MPPI): A sampling-based, gradient-free control method rooted in path integral formulations. "search-based methods such as the Cross Entropy Method (CEM)~\citep{rubinstein2004cross} and Model Predictive Path Integral control (MPPI)~\citep{williams2017model} have been widely adopted as gradient-free alternatives and have proven effective in practice."

- Model-based planning: Planning that leverages a learned or known dynamics model to evaluate and optimize action sequences. "World models are compatible with many model-based planning algorithms."

- Next-state prediction objective: A training objective where the model predicts the next latent state given the current state and action. "World models are typically trained using a next-state prediction objective on datasets of expert trajectories."

- Online World Modeling: A finetuning approach that uses simulator-corrected planner rollouts to expand training distribution and reduce errors. "To address this issue, we propose Online World Modeling, which iteratively corrects the trajectories produced by GBP and finetunes the world model on the resulting rollouts."

- Open-loop planning: Planning where the full action sequence is optimized once and executed without feedback between steps. "In the open-loop setting, we run \Cref{algo:gbp} from once and evaluate the predicted action sequence."

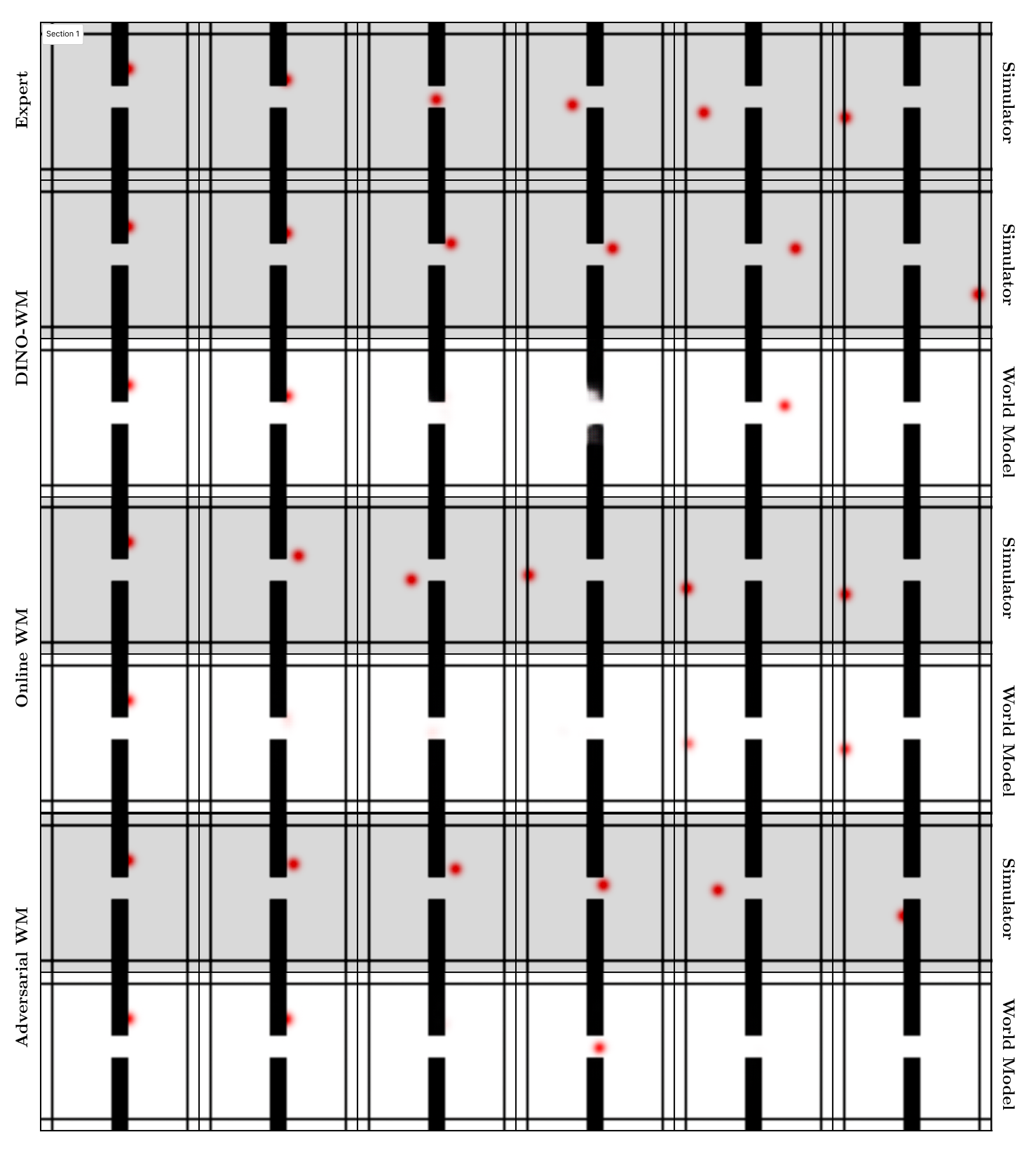

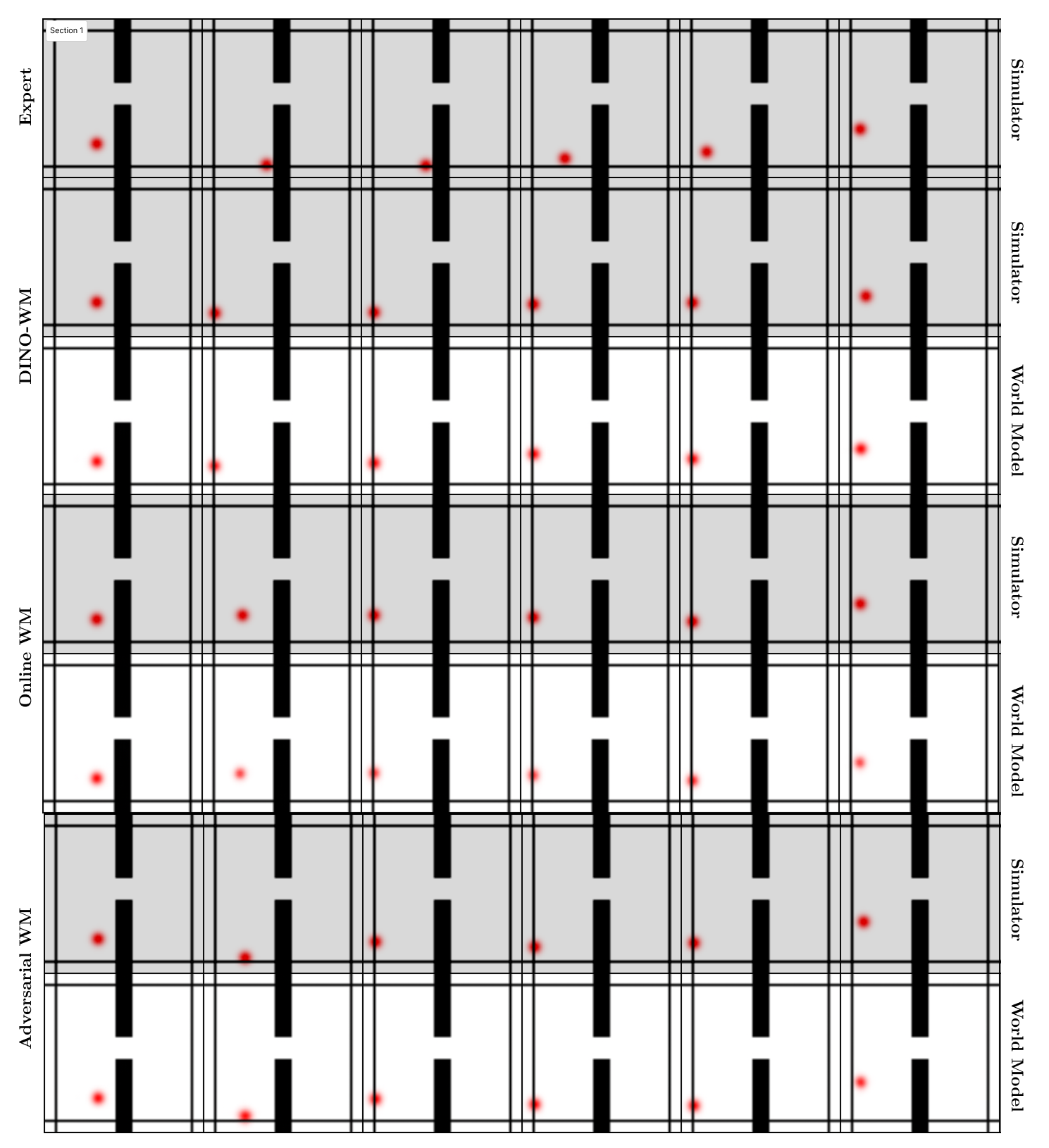

- Optimization landscape: The structure of an objective over action or parameter space, including basins and local minima. "Optimization landscape of DINO-WM \citep{zhou2025dinowmworldmodelspretrained} before and after finetuning with our Adversarial World Modeling objective on the Push-T task."

- Out-of-distribution states: States not represented in the training data, where model predictions can fail or compound errors. "In these out-of-distribution states, model errors compound, making the world model unreliable as a surrogate for optimization."

- Pixel-space prediction methods: Approaches that predict future observations directly in pixel space, often costly due to image reconstruction. "Pixel-space prediction methods~\citep{Finn2016UnsupervisedLFA, Kaiser2019ModelBasedRL} have shown success in applications such as human motion prediction~\citep{Finn2016UnsupervisedLFA}, robotic manipulation~\citep{Finn2016DeepVF, agrawal2016learning, zhang2019solar}, and solving Atari games~\citep{Kaiser2019ModelBasedRL}"

- Projected Gradient Descent (PGD): An iterative adversarial attack that performs gradient ascent steps constrained within a perturbation set. "Although stronger iterative attacks such as Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) can be used, we find that FGSM delivers comparable improvements in GBP performance"

- Rollout: Simulating the dynamics forward over a sequence of actions to evaluate outcomes or objectives. "search-based methods such as the Cross Entropy Method (CEM)~\citep{rubinstein2004cross} and Model Predictive Path Integral control (MPPI)~\citep{williams2017model} have been widely adopted as gradient-free alternatives and have proven effective in practice. However, they are computationally intensive as they require iteratively sampling candidate solutions and performing world model rollouts to evaluate each one"

- Simulator: A ground-truth dynamics function used to obtain corrected trajectories or evaluate predictions. "using the true dynamics simulator "

- Teacher-forcing objective: A training approach using ground-truth next states to supervise one-step predictions, avoiding compounding errors. "This procedure is represented by the following teacher-forcing objective:"

- Train-test gap: The mismatch between training objectives/data and test-time planning usage that degrades performance. "This procedure suffers from a fundamental train-test gap."

- ViT (Vision Transformer): A transformer-based architecture used to implement the transition model in the world model. " is implemented using the ViT architecture ~\citep{dosovitskiy2021imageworth16x16words}."

- VQVAE (Vector-Quantized Variational Autoencoder): A generative model with discrete latent codes, used here to visualize latent states. "We additionally train a VQVAE decoder ~\citep{oord2018neuraldiscreterepresentationlearning} to visualize latent states, though it plays no role in planning."

- World model: A learned dynamics model that predicts how states evolve under actions, enabling planning and control. "World models \citep{ha2018world}, in particular, have emerged as a powerful paradigm."

Practical Applications

Practical Applications of “Closing the Train-Test Gap in World Models for Gradient-Based Planning”

Below we translate the paper’s contributions—Online World Modeling (OWM) and Adversarial World Modeling (AWM)—into concrete, real-world applications. Each item notes sector relevance, candidate tools/products/workflows, and key assumptions or dependencies affecting feasibility.

Immediate Applications

These can be deployed now with existing datasets, simulators, and off-the-shelf models (e.g., DINO-WM, IRIS), especially in settings where planners already use MPC, simulators, or offline logs.

- Robotics: Drop-in replacement for CEM with faster gradient-based planning (GBP)

- Sector: Robotics (industrial manipulation, mobile robots, drones)

- What: Replace sampling-based planners (e.g., CEM) with GBP enhanced by AWM/OWM to achieve comparable or better performance at ~10× lower compute/time budgets.

- Tools/workflows:

- ROS2 plugin/module for GBP (Adam optimizer + weighted goal loss) integrated with existing world models.

- Model-serving pipeline for ViT-based transition models with frozen DINOv2 encoders.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- A pre-trained latent world model exists for the task domain.

- Action constraints and safety checks implemented around the planner.

- Adequate GPU/CPU for backprop at control frequency.

- Onboard real-time MPC on constrained hardware

- Sector: Warehousing (AGVs), logistics robots, UAVs

- What: Use AWM-smoothed world models to run real-time GBP-based MPC where CEM is too slow; supports frequent re-planning with tight latency budgets.

- Tools/workflows:

- Embedded inference pipelines (TensorRT/ONNX) for ViT transitions.

- Fixed-horizon MPC with re-planning every K steps; latency monitoring.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Deterministic inference timing; bounded action spaces; robust fallback (e.g., safe stop or CEM in low-frequency background).

- Simulator-in-the-loop model finetuning for robust planning

- Sector: Robotics R&D, autonomous systems validation

- What: Use OWM to finetune world models by correcting off-distribution GBP trajectories with a simulator (DAgger-like), closing the train-test gap before deployment.

- Tools/workflows:

- Integration with MuJoCo/Isaac Gym/PyBullet simulators.

- Automated “planner-in-the-loop” data aggregation and retraining jobs.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Access to a sufficiently accurate simulator; sim2real gap mitigations (domain randomization, calibration).

- Robustness-oriented data augmentation for world models without simulation

- Sector: Robotics and autonomy teams lacking high-fidelity simulators

- What: Apply AWM (FGSM-based latent/action perturbations) to offline datasets to smooth the planning loss landscape, improve stability of GBP without rolling in a simulator.

- Tools/workflows:

- Training augmentation toolkit for adversarial latent/action perturbations with tunable ε scales (λa, λz).

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Sufficiently diverse offline logs; quality of latent encoder (e.g., DINOv2) generalizes to task states.

- Faster simulated training loops for model-based control

- Sector: Software for robotics simulation and training

- What: Replace CEM with GBP during iterative training and benchmarking to reduce compute bill and wall-clock time for experiments.

- Tools/workflows:

- Experiment manager switching between CEM and GBP; time-to-solution dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Comparable task success targets; reliable early-stopping criteria.

- Teaching and academic benchmarking of model-based planning

- Sector: Academia/education

- What: Use AWM/OWM in coursework and labs to demonstrate closing the train-test gap, adversarial finetuning benefits, and MPC with latent world models.

- Tools/workflows:

- Reproducible notebooks using DINO-WM/IRIS; metrics for train-test error gaps and landscape smoothness; standard tasks (PushT, PointMaze, Wall).

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Access to GPUs; open datasets; clear evaluation protocols.

- Game AI and simulation agents

- Sector: Software/gaming

- What: Use GBP-enabled world models for efficient trajectory optimization of NPCs in continuous or hybrid action spaces.

- Tools/workflows:

- Unity/Unreal plugin for latent world modeling with GBP; curriculum finetuning with AWM.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Game physics/world dynamics captured by the model; latency and determinism requirements met.

- QA and safety monitoring via train-test gap metrics

- Sector: Industry QA, policy/compliance inside engineering orgs

- What: Introduce a dashboard tracking world-model error on expert vs. planning trajectories (Δ metrics) to detect dangerous distribution shifts pre-deployment.

- Tools/workflows:

- MLOps metric logging; trigger retraining with OWM/AWM on threshold breaches.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Access to representative planning rollouts for evaluation; standardized thresholds tied to safety cases.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling to complex domains, tighter safety cases, and/or integration with high-fidelity or real-world data.

- Autonomous driving and advanced driver assistance trajectory planning

- Sector: Automotive

- What: Robust GBP built on adversarially finetuned latent world models for real-time trajectory optimization (merging, obstacle avoidance) at lower compute than sampling-based MPC.

- Tools/products:

- World-model planner module that interfaces with perception stacks and enforces kinematic and safety constraints.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- High-fidelity learned multi-agent dynamics; strong OOD generalization; rigorous verification and regulatory approval.

- Surgical and medical robotics

- Sector: Healthcare

- What: Low-latency planning around tissue/tool interactions using improved GBP; faster replanning than sampling-based methods.

- Tools/products:

- Regulatory-compliant training pipelines using AWM with clinically curated datasets; constrained MPC wrappers.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Verified biomechanical world models; stringent safety validation/certification.

- Generalist household robots with hierarchical world models

- Sector: Consumer robotics

- What: Combine AWM/OWM with multi-timescale/hierarchical planners to stabilize long-horizon tasks (e.g., tidy room, cooking subtasks) using latent JEPA-like models.

- Tools/products:

- Hierarchical world-model SDK; household task libraries; on-device GBP.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Scalable representation learning across diverse household scenes; robust manipulation primitives; safety interlocks.

- Multi-robot/drone swarms with cooperative planning

- Sector: Aerospace, logistics, defense

- What: Differentiable multi-agent world models to enable coordinated GBP with real-time MPC across agents.

- Tools/products:

- Communication-aware world models; decentralized GBP modules with shared latent states.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Accurate multi-agent dynamics; communication constraints; collision-avoidance and formal guarantees.

- Industrial process control and energy systems

- Sector: Energy, manufacturing

- What: Apply robust, differentiable MPC with learned world models for building HVAC optimization, grid control, or chemical process set-points where sampling-based controllers are costly.

- Tools/products:

- Domain-specific latent encoders (time-series) and AWM finetuning; real-time GBP controller with constraints.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Reliable telemetry-based world models beyond vision; safety envelopes and fail-safes; explainability requirements.

- Sim-to-real adaptation via real-world “correction loops”

- Sector: Robotics (field deployment)

- What: Extend OWM by using cautious, safety-capped real executions to correct planner-induced trajectories, gradually adapting world models on-device.

- Tools/products:

- Safe exploration wrappers; incremental dataset aggregation with human-in-the-loop approvals.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Risk-managed execution; strong supervisory control; automated anomaly detection.

- Standardization and certification of robustness for learned planners

- Sector: Policy/regulation

- What: Define evaluation protocols for adversarial robustness and train-test gap metrics specific to model-based planners; incorporate into certification regimes.

- Tools/products:

- Benchmark suites and reporting standards for planning robustness; conformance tests.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Industry consensus; mapping metrics to safety risk; regulator engagement.

- Edge deployment and hardware co-design for differentiable planning

- Sector: Semiconductors/embedded systems

- What: Co-design accelerators optimized for backprop-based planning loops (short-horizon rollouts + gradient steps), enabling GBP at the edge.

- Tools/products:

- Compiler support for tiny ViTs; fused rollout-gradient kernels; latency-bounded scheduling.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Stable model architectures; predictable memory footprints; sufficient demand for on-device planning.

- Cross-domain foundation world models for planning

- Sector: AI platforms

- What: Large, multimodal JEPAs/world models trained on diverse physical interaction data, then finetuned with AWM/OWM to provide planning-as-a-service across domains.

- Tools/products:

- Planning APIs; goal-conditioned GBP endpoints; dataset hubs for offline trajectories.

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Massive, diverse datasets; robust latent spaces shared across tasks; governance for data provenance and safety.

Key Assumptions and Dependencies (General)

- World model quality: Success hinges on strong latent representations (e.g., DINOv2) and a well-trained transition model (ViT/IRIS); poor representations limit planning gains.

- Goal specification: Goals must be expressible in latent space; reward shaping or goal encoders may be required for non-visual tasks.

- Safety and constraints: GBP can exploit model inaccuracies; action limits, collision checks, and constraint handling are essential in real systems.

- Data availability: OWM needs simulators (or safe real-world correction loops); AWM needs diverse offline trajectories for meaningful adversarial augmentation.

- Compute and latency: While GBP is faster than CEM, guaranteed real-time performance depends on model size, horizon H, and optimizer iterations.

- Domain shift: Sim-to-real gaps and OOD events still require monitoring (train-test gap metrics) and fallback strategies (e.g., degrade gracefully to safer controllers).

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.