RVC-NMPC: Nonlinear Model Predictive Control with Reciprocal Velocity Constraints for Mutual Collision Avoidance in Agile UAV Flight (2512.08574v1)

Abstract: This paper presents an approach to mutual collision avoidance based on Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC) with time-dependent Reciprocal Velocity Constraints (RVCs). Unlike most existing methods, the proposed approach relies solely on observable information about other robots, eliminating the necessity of excessive communication use. The computationally efficient algorithm for computing RVCs, together with the direct integration of these constraints into NMPC problem formulation on a controller level, allows the whole pipeline to run at 100 Hz. This high processing rate, combined with modeled nonlinear dynamics of the controlled Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), is a key feature that facilitates the use of the proposed approach for an agile UAV flight. The proposed approach was evaluated through extensive simulations emulating real-world conditions in scenarios involving up to 10 UAVs and velocities of up to 25 m/s, and in real-world experiments with accelerations up to 30 m/s$2$. Comparison with state of the art shows 31% improvement in terms of flight time reduction in challenging scenarios, while maintaining a collision-free navigation in all trials.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about helping many fast-moving drones fly safely together without crashing into each other. The authors designed a smart control method that tells each drone how to move so it avoids others, even at high speeds, using only simple information it can observe (like where other drones are and how fast they’re going). It runs very quickly—100 times per second—so it can react fast enough for agile flight.

What questions does the paper try to answer?

- How can multiple drones avoid each other reliably at high speeds without constantly sharing detailed plans over a network?

- Can we make collision avoidance work using only what a drone can see or receive with low-bandwidth signals (current positions and velocities), instead of needing other drones’ future paths?

- Can this be done while respecting each drone’s physical limits (like maximum speed, acceleration, and motor power)?

- Will it work in real-life conditions with delays, noise, and many drones?

How does the method work? (Explained with everyday examples)

Think of each drone as a skilled skateboarder in a crowded park:

- Each skateboarder knows where others are and how fast they’re moving right now.

- No one shares a detailed plan of their next moves; they just react smartly and quickly.

The paper combines three main ideas:

- A quick “reference path” to the goal The drone makes a fast, simple plan towards its destination that respects limits like top speed and maximum acceleration. This is like sketching a quick route that’s safe for your skateboard tricks.

- “Reciprocal Velocity Constraints” (RVC) to avoid collisions

Imagine two skateboarders heading toward each other. There’s a set of speed directions that would make them bump; that’s called a “velocity obstacle.”

- The “reciprocal” part means both share the responsibility to avoid the collision—each adjusts a bit, instead of one doing all the work.

- The method turns this idea into simple rules about which speeds are allowed right now. These rules are linear (think straight-line boundaries), so they’re fast to compute.

Time-dependent twist: The rules only stay active while the two drones are truly on a collision course. As soon as their relative directions no longer point toward each other, the constraints switch off. This helps drones move faster without being overly cautious.

- A fast controller that uses the drone’s real physics

The drone uses “Nonlinear Model Predictive Control” (NMPC), which is like a mini planner that looks a short time ahead, 100 times per second, and chooses motor thrusts that follow the reference path while obeying the collision-avoidance rules and the drone’s physical limits.

- “Nonlinear” here means it respects real physics (forces, rotation), like a good video game physics engine.

- The collision constraints are “soft,” so if there’s ever a moment where all rules can’t be met perfectly, the controller doesn’t freeze; it makes the best possible safe choice.

Why only use current information? Because at high speeds, future plans can change quickly, and heavy communication is slow or unreliable. By using only what’s visible now (positions and velocities), drones stay responsive. If messages arrive late, a simple prediction fills in the gaps for a moment.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

- It works fast: The whole method runs at about 100 Hz (100 times per second) on a modest processor, making it suitable for agile flight.

- It handles real physics: The controller considers the drone’s real dynamics and motor limits, not just simplified math.

- It scales to multiple drones: In simulations with up to 10 drones moving up to 25 m/s and accelerating up to 40 m/s², the system avoided collisions over long tests.

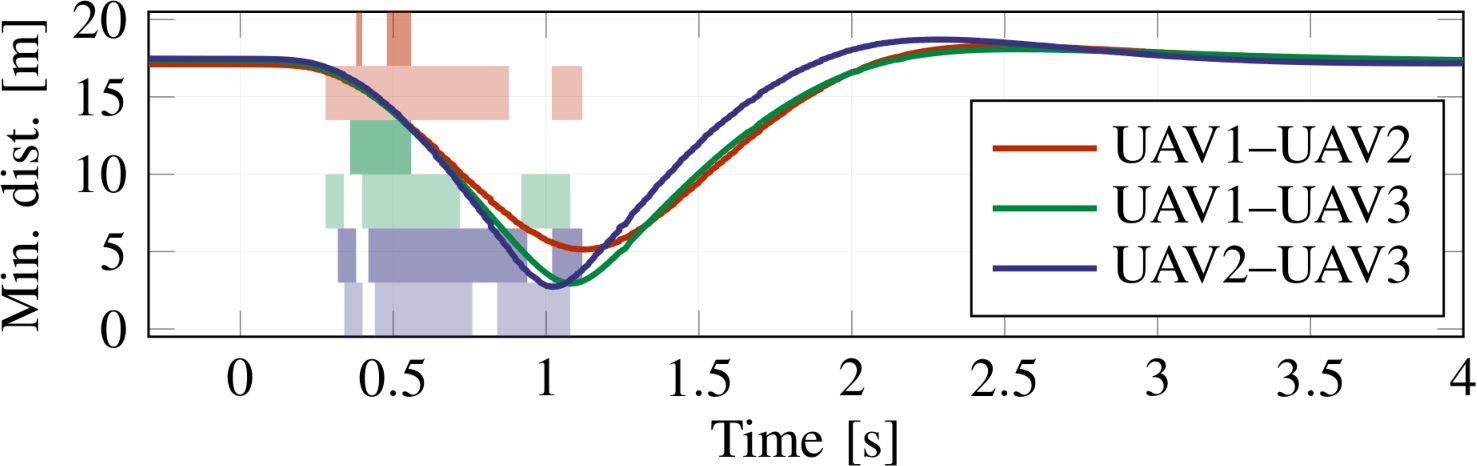

- It works in the real world: In experiments with three drones, they reached speeds up to 18 m/s and accelerations up to 30 m/s² without crashing.

- It’s faster than other methods: In a tough scenario designed to create lots of crossing paths, this method completed flights about 31% quicker than the best competing approach, while still avoiding collisions.

- It’s robust: It handled communication delays and noisy measurements well.

This is important because many previous methods either:

- Required sharing future paths (heavy communication), or

- Ignored the drone’s real physical limits, or

- Didn’t work reliably above about 10 m/s.

This method avoids those pitfalls.

What does this mean for the future?

- Safer, faster drone fleets: Delivery drones, search-and-rescue teams, and inspection swarms could fly closer and faster without crashing, even if they don’t constantly share detailed plans.

- Less reliance on strong networks: Using only positions and velocities makes it friendly to low-bandwidth systems (like Remote ID), onboard sensing, or noisy environments.

- Practical agility: Respecting real physics means it’s more likely to work reliably in the field, not just in theory.

The authors note they don’t provide strict mathematical guarantees for every situation, but the approach shows strong practical results. Future work could add formal safety guarantees, handle even larger fleets, and extend to cluttered environments with buildings or trees.

Knowledge Gaps

The paper leaves the following knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that future work could address:

- Absence of formal safety guarantees: no proof that time-dependent reciprocal velocity constraints (RVCs) embedded in NMPC ensure collision avoidance, especially when constraints are softened via slack variables.

- Unproven claim that a single set of constraints computed at the current state and applied over the entire horizon guarantees safety when τ ≥ T_h; the required conditions on dynamics, constraint softness, and other agents’ behaviors are unspecified.

- Lack of principled guidance for choosing prediction horizon N and the ORCA time window τ (e.g., relations to speed/acceleration bounds, control rate, sensing delays, and r_ca) to achieve guaranteed safety and performance.

- Time-validity t_{v,m} derivation assumes constant relative velocity; there is no robustness analysis or alternative formulation when neighboring agents accelerate or change intent.

- Handling of non-cooperative or adversarial agents is not addressed; ORCA-style equal responsibility may fail if other agents do not comply or use different policies.

- Soft constraints (slack variables) can permit constraint violations; no bounds on slack magnitudes, no risk quantification, and no emergency fallback (e.g., prioritized braking, altitude separation) are provided.

- No strategy for infeasible intersections of multiple half-space constraints (empty feasible velocity set); the reliance on slacks lacks safety assurances in dense encounters.

- Scalability beyond 10 UAVs is unquantified: computational complexity, solver convergence, and achievable control frequency at larger swarm sizes/densities are not measured or analyzed.

- Robustness to sensing/communication imperfections is only qualitatively mentioned; explicit bounds on tolerable delay, jitter, dropout duration, out-of-order messages, and state-estimation noise for safety are missing.

- Onboard detection failure modes (occlusions, false positives/negatives, intermittent tracking) and their mitigation (e.g., uncertainty-aware sets, confidence gating) are not evaluated.

- Other-agent prediction uses a constant-velocity model; bounded-acceleration sets, probabilistic/chance constraints, or tube-based approaches are not explored to improve robustness.

- Dynamic model fidelity: linear drag is assumed, while high-speed flight generally exhibits quadratic drag and wind/gust effects; the impact of aerodynamic model mismatch on NMPC feasibility and safety is not analyzed.

- Aerodynamic interactions (downwash, wake effects) in close proximity are ignored; constraints for vertical separation or anisotropic safety regions are not modeled.

- Applicability to heterogeneous platforms (e.g., fixed-wing UAVs, different nonholonomic models) is claimed but not demonstrated; necessary model adaptations and validations are absent.

- Environmental complexity: evaluations focus on obstacle-free scenarios; integration of static/dynamic obstacles into the NMPC and RVC framework (and performance in clutter) is left unexplored.

- Deadlock/livelock risks (e.g., “reciprocal dances” in symmetric encounters) are not analyzed; no liveness guarantees or anti-oscillation mechanisms are proposed.

- Parameter tuning is ad hoc: there is no principled method to select r_ca, Q/R/Z weights, or slack penalties based on vehicle size, localization errors, and desired safety margins.

- Inconsistent radii in evaluation (e.g., r_ca = 0.6 m vs. collision checking at 0.25 m) without rationale; the effect of this margin on safety and performance is not quantified.

- Stability and recursive feasibility of the NMPC scheme (with time-varying constraints and slacks) are not established; formal analysis or broad empirical evidence is missing.

- Solver and numerical details (optimizer choice, horizon length, time step, warm-start, convergence rates, failure handling, and fallback behavior) are unspecified, hindering reproducibility and robustness assessment.

- Interaction between PMM reference generation and NMPC tracking is not analyzed (e.g., mismatch between point-mass references and full dynamics, curvature limits, and feasibility under active constraints).

- Adaptive scheduling is absent: fixed 100 Hz update rate and static τ/t_{v,m} may be suboptimal; no policies to adapt horizon or constraint validity based on speed, density, or communication quality.

- Safety in 3D with anisotropic constraints (e.g., larger vertical separation due to downwash or regulatory altitude rules) is not considered; RVCs are isotropic in velocity space.

- Real-world validation is limited (three UAVs, up to 18 m/s); larger-scale, higher-speed experiments with diverse environmental and operational conditions are needed.

- Interaction with non-UAV air traffic and regulatory systems (e.g., Remote ID update rates, communication range/reliability) is not addressed; operational requirements and compliance strategies remain open.

Glossary

- Body frame: A coordinate frame fixed to the vehicle used to express forces, torques, and velocities relative to the vehicle. "in the body frame"

- Deadlock: A standstill situation where multiple agents block each other and none can make progress without coordination. "deadlock prevention"

- Downwash: The downward airflow generated by rotors that can affect nearby vehicles’ dynamics and safety. "integrating the downwash in the \ac{orca} algorithm"

- Flatness-based feedforward linearization: A control design technique that uses differential flatness to pre-cancel nonlinearities through feedforward terms. "flatness-based feedforward linearization"

- Flight Control Unit (FCU): The onboard controller that converts high-level control inputs into low-level motor commands. "passed to Flight Control Unit"

- Hadamard product: Element-wise multiplication of vectors or matrices. "where stands for Hadamard product"

- Minkowski sum: The set obtained by adding every element of one set to every element of another set in a vector space. "operator denotes Minkovski sum."

- Model Predictive Control (MPC): An optimization-based control scheme that repeatedly solves a finite-horizon problem to compute control actions. "use ORCA constraints directly in a MPC formulation"

- Nonholonomic models: System models with non-integrable motion constraints that limit feasible velocities or directions. "nonholonomic models"

- Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC): MPC that explicitly handles nonlinear system dynamics and constraints. "NMPC Controller"

- Optimal Reciprocal Collision Avoidance (ORCA): A decentralized collision-avoidance method where each agent shares responsibility to avoid collisions by selecting velocities outside conflict sets. "ORCA constraints"

- Point-mass model: A simplified dynamics model that treats a vehicle as a point with mass subject to kinematic limits. "point-mass model minimum-time trajectory generation approach"

- Quadrotor: A four-rotor aerial vehicle whose motion is controlled via differential rotor thrusts and torques. "The quadrotor dynamics can be described as:"

- Quaternion: A four-parameter representation of 3D orientation with a non-commutative multiplication operation. "quaternion multiplication"

- Reciprocal Velocity Constraints (RVC): Linear constraints on agent velocities that ensure mutual collision avoidance when enforced reciprocally. "reciprocal velocity constraints"

- Remote Drone ID: A broadcast mechanism for drones to share identity and basic state information over low bandwidth. "as part of the Remote Drone ID"

- Runge–Kutta method: A family of numerical integrators for solving ordinary differential equations. "discretized using the Runge-Kutta method"

- Slack variables: Auxiliary variables that relax constraints to maintain feasibility at the cost of a penalty in the objective. "with slack variables "

- SO(3): The Lie group of 3D rotation matrices representing orientations in three-dimensional space. "unit quaternion rotation "

- Soft constraints: Constraints that may be violated with an associated penalty, preserving problem feasibility. "applied as soft constraints"

- Velocity Obstacle (VO): The set of relative velocities that would lead to a collision within a given time horizon. "The velocity obstacle "

- V-RVO: A variant of Reciprocal Velocity Obstacles that assigns variable responsibility to agents for collision avoidance. "V-RVO~\cite{arul2021vrvo}"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are near-term, deployable uses that can leverage the paper’s RVC‑NMPC method with minimal adaptation.

- High-speed tactical detect-and-avoid for multi-UAV operations in shared airspace

- Sector: aerospace/UTM, public safety

- Tools/products/workflows: PX4/ArduPilot Offboard controller with an RVC‑NMPC ROS2 node; Remote ID or ADS‑B telemetry bridge; “tactical deconfliction” mode that gates mission references through the controller at ~100 Hz

- Assumptions/dependencies: availability of own-state (GNSS/RTK or VIO + IMU) and other agents’ position/velocity (via Remote ID or onboard detection); companion computer (~2 GHz ARM-class) to run NMPC at 100 Hz; acceptance as a tactical safety layer (no formal safety guarantees yet); reciprocal behavior expected from other cooperative UAVs or conservative responsibility assignment for non-cooperative intruders

- Concurrent infrastructure inspections by multiple drones (power lines, solar farms, wind turbines, construction)

- Sector: energy, construction, oil & gas

- Tools/products/workflows: mission planner that assigns inspection waypoints per UAV; onboard decentralized collision-avoidance using only position/velocity sharing or onboard sensing; logging/telemetry for safety cases

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable state estimation (GNSS/RTK in open areas; VIO/LiDAR in clutter); modest fleet sizes (tested up to ~10 agents); wind/gust margins handled by controller tuning; agreed safety radii

- Warehouse/intralogistics indoor inventory drones operating in fleets

- Sector: logistics, retail

- Tools/products/workflows: VIO/UWB-based localization; peer detection via UWB-ranging, vision, or LiDAR; WMS integration; RVC‑NMPC as the local safety layer while tasking remains decentralized

- Assumptions/dependencies: GPS-denied localization; reliable peer-state estimates in occlusive aisles; speed limits compatible with human safety; obstacle avoidance for static shelving integrated alongside mutual avoidance

- Drone light shows and multi-camera cinematography safety layer

- Sector: media/entertainment

- Tools/products/workflows: choreography/shot planner generates references; RVC‑NMPC enforces reciprocal velocity constraints as a guardrail during deviations (wind, GPS glitches); emergency braking behavior via soft constraint slack

- Assumptions/dependencies: sufficient onboard compute; careful integration to avoid altering choreography beyond acceptable limits; preflight validation in simulation; RF coordination for telemetry if used

- Inter-agency emergency operations with ad-hoc multi-UAV deconfliction

- Sector: public safety, disaster response

- Tools/products/workflows: smartphone/edge appliance that aggregates Remote ID broadcasts; a cross-vendor ROS2 node running RVC‑NMPC; on-scene “plug-in” collision-avoidance retrofit for diverse fleets

- Assumptions/dependencies: uneven equipage and skill levels; variable latency and packet loss (method robust to moderate delays); policy approval to use Remote ID for tactical deconfliction; fallback for non-cooperative aircraft

- Academic testbeds and coursework for decentralized multi-robot control

- Sector: academia

- Tools/products/workflows: open-source ROS2/Gazebo/FlightGoggles modules implementing RVC‑NMPC; reproducible APCX scenario (antipodal circle crossing) for benchmarking; ablation studies for communications/noise

- Assumptions/dependencies: open-source availability; safety cages; hardware-in-the-loop capability or low-cost companion computers

- Ports, mining pits, and construction site mapping with multi-UAV teams

- Sector: geospatial, AEC (architecture/engineering/construction), mining

- Tools/products/workflows: waypoint distribution per asset/sector; RVC‑NMPC as a decentralized safety layer to cut idle time during concurrent area coverage; post-mission audit logs

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable GNSS in open areas; site-specific geofences; incident procedures for unexpected intruders (helicopters, cranes)

- OEM SDK for “decentralized collision-avoidance” add-on

- Sector: software, UAV OEMs

- Tools/products/workflows: vendor-agnostic SDK offering: (1) RVC generation from observed states, (2) NMPC controller bindings, (3) tuning UI; CI pipeline with scenario-based regression tests (e.g., APCX)

- Assumptions/dependencies: integration effort with different FCUs; compute and latency budgets; support for ROS2/MAVLink bridges; liability and warranty considerations

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities require further research, scaling, validation, or certification before widespread deployment.

- Certified detect-and-avoid (DAA) for high-density UTM/U‑space and urban air mobility (UAM)

- Sector: aerospace/UTM, policy/regulatory

- Tools/products/workflows: safety-certified avionics module implementing RVC‑NMPC with monitors; formal verification or runtime assurance (e.g., reachability/barrier-function supervisors); standard V&V test suites

- Assumptions/dependencies: formal safety guarantees and assurance cases; redundancy and fail-operational capability; standards alignment (ASTM F3442, EUROCAE ED‑78/ED‑279); integration with strategic deconfliction and conformance monitoring

- City-scale last-mile delivery without high-bandwidth trajectory sharing

- Sector: logistics, e-commerce

- Tools/products/workflows: fleet management that issues goals only; tactical RVC‑NMPC on each vehicle; adoption of broadcast-only peer-state (Remote ID) with low-latency edge relays; “RVC corridors” as operational rules

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust perception or reliable broadcast coverage in urban canyons; handling of non-cooperative traffic (GA aircraft, birds); obstacle-rich environments require combined static-obstacle planning + RVC; regulatory maturation for BVLOS at scale

- Cross-domain traffic management for heterogeneous robots (air/ground/marine)

- Sector: robotics, logistics, smart infrastructure

- Tools/products/workflows: generalized RVC for different dynamic models; multi-domain simulators; shared minimal state interfaces; site-wide decentralized traffic rules

- Assumptions/dependencies: heterogeneous dynamics and responsibility assignment; standardized message formats; indoor/outdoor localization interoperability

- Consumer drones with built-in “mutual safety” mode for recreational swarms

- Sector: consumer electronics

- Tools/products/workflows: firmware integration leveraging onboard SoCs (DSP/GPU) for 100–200 Hz NMPC; simple UI toggles; interoperability profiles for different brands

- Assumptions/dependencies: compute and battery overhead; RF coexistence; minimal user setup; user education and liability frameworks

- Onboard-only deconfliction with all-weather perception for non-cooperative traffic

- Sector: aerospace, sensing

- Tools/products/workflows: radar/LiDAR/vision-based drone detection and tracking; low-latency sensor fusion; uncertainty-aware RVC‑NMPC

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable detection ranges at high relative speeds; occlusion handling; elevated compute and power; rigorous datasets for training/validation

- Formal safety guarantees for RVC‑NMPC via robust control/verification

- Sector: academia, safety engineering

- Tools/products/workflows: integration of control barrier functions, tube‑MPC, or reachability analysis; probabilistic guarantees (chance constraints) for uncertainty; runtime monitors with fallback policies

- Assumptions/dependencies: computational tractability at ≥100 Hz; conservative margins vs. performance; scalable proofs for many-agent systems

- Swarm autonomy in GPS-denied or harsh environments (indoor, tunnels, urban canyons)

- Sector: mining, public safety, critical infrastructure

- Tools/products/workflows: cooperative localization (UWB/VIO/SLAM); relative-state RVC with uncertainty bounds; mesh networking; resilient behaviors under signal loss

- Assumptions/dependencies: drift management; robust relative-ranging in occlusive spaces; safety with human workers; integration with static obstacle mapping

- Hardware-accelerated NMPC for extreme agility or very large swarms

- Sector: hardware, embedded systems

- Tools/products/workflows: GPU/DSP/FPGA acceleration to push 100→200–500 Hz control and longer horizons; autotuning tools; power-aware scheduling

- Assumptions/dependencies: thermal/power constraints on small airframes; maintainable toolchains; certification of accelerated components in safety-critical contexts

Notes on Method-Specific Assumptions and Dependencies

- Observability and communication: The approach assumes access to other agents’ positions and velocities, via low-bandwidth broadcast (e.g., Remote ID) or onboard perception. Performance degrades with severe latency, dropouts, or poor detections.

- Reciprocity: The RVC design shares responsibility (ORCA-style). For non-cooperative agents, responsibility weighting must be biased conservatively; otherwise, safety margins need to increase.

- Dynamics and tuning: NMPC requires a reasonably accurate dynamic model and tuning of weights/constraints. Platform-specific identification and validation are needed.

- Scale and speed: Demonstrated up to 10 UAVs and ≤25 m/s in sim, ≤18 m/s in real tests. Scaling beyond requires validation and likely compute upgrades.

- Obstacles: The work focuses on inter-robot avoidance. Integration with static/unknown obstacle avoidance is necessary for cluttered environments.

- Certification: No formal safety guarantees are claimed; regulatory adoption as a primary DAA requires further analysis, testing, and assurance.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.