Training-Time Action Conditioning for Efficient Real-Time Chunking (2512.05964v1)

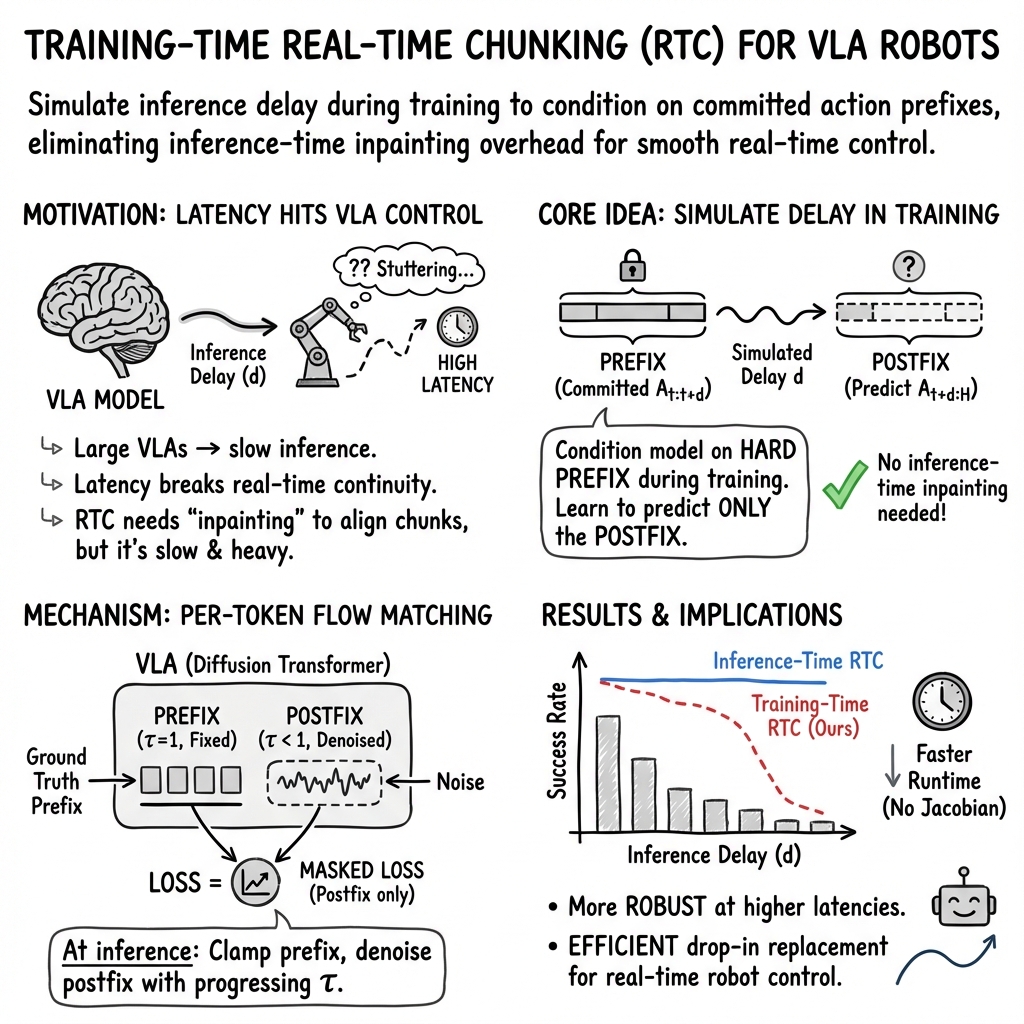

Abstract: Real-time chunking (RTC) enables vision-language-action models (VLAs) to generate smooth, reactive robot trajectories by asynchronously predicting action chunks and conditioning on previously committed actions via inference-time inpainting. However, this inpainting method introduces computational overhead that increases inference latency. In this work, we propose a simple alternative: simulating inference delay at training time and conditioning on action prefixes directly, eliminating any inference-time overhead. Our method requires no modifications to the model architecture or robot runtime, and can be implemented with only a few additional lines of code. In simulated experiments, we find that training-time RTC outperforms inference-time RTC at higher inference delays. In real-world experiments on box building and espresso making tasks with the $π_{0.6}$ VLA, we demonstrate that training-time RTC maintains both task performance and speed parity with inference-time RTC while being computationally cheaper. Our results suggest that training-time action conditioning is a practical drop-in replacement for inference-time inpainting in real-time robot control.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about helping robots act smoothly and quickly in the real world using big AI models that look at images, understand language, and produce actions (called vision-language-action models, or VLAs). When a robot uses a large model, it can be slow to think. The paper introduces a simple way to make the robot’s movements stay smooth even when the model takes time to produce the next set of actions. The trick is to teach the model during training how to handle delays, instead of doing extra complicated computations while the robot is running.

Key Questions and Goals

The researchers focused on a practical problem: how can we keep robot movements smooth and reactive when the model’s “thinking time” causes delays? Specifically, they wanted to:

- Keep robot actions continuous (no jerky motion) even when the model’s predictions arrive late.

- Avoid extra heavy computation while the robot is moving.

- Make a solution that works with existing models and robot systems without big changes.

- Compare their training-time method to a common alternative that fixes things during robot operation (called inference-time inpainting).

Methods and How They Work (in Simple Terms)

Think of a robot planning its moves like writing a short “to-do” list of actions, called a chunk. For example, a chunk might be the next 8 tiny movements of its arm. Because the AI model takes time to create the next chunk, the robot starts executing the current chunk while the next one is being prepared. This overlap can cause a problem: the start of the new chunk needs to match the actions the robot has already committed to, or the motion will “jerk.”

Here are the key ideas explained with everyday analogies:

- Action chunks: Short sequences of moves (like writing the next few steps in a dance).

- Delay (): The time it takes the AI to produce those next steps. If the model takes longer, you get a bigger delay.

- Prefix: The part of the action chunk the robot has already committed to (like the first few dance steps already started).

- Postfix: The rest of the action chunk the model still needs to finish (the remaining dance steps).

- Real-time chunking (RTC): The system generates the next chunk while executing the current one and tries to make them flow together smoothly.

What’s new in this paper:

- Prior method (inference-time inpainting): While the robot is moving, the model does extra math to “fill in” the rest of the chunk so it connects nicely to the already-committed actions. This works but adds extra computation during operation, making the robot slower.

- Proposed method (training-time action conditioning): Instead of fixing things at run time, the model is trained to expect delays. During training, the model is fed the already-fixed “prefix” actions and learns to predict the remaining “postfix” so that it lines up perfectly. This way, when the robot is running, the model doesn’t need extra expensive fixes—it already knows how to handle the delay.

A bit more about the training setup, simplified:

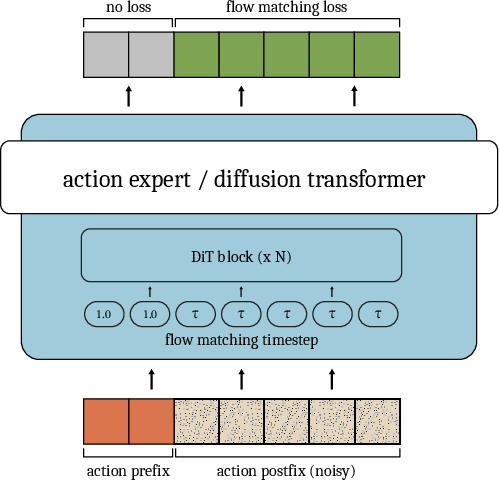

- The model learns to turn noisy guesses into correct actions gradually (a process called “flow matching,” similar to cleaning up a blurry picture until it’s clear).

- During training, the first part (prefix) is given as the ground-truth actions (no noise), and the model only has to “denoise” the rest (postfix).

- The training randomly uses different delays so the model becomes robust to various real-world timing.

Importantly, this approach:

- Doesn’t need changes to the robot’s software.

- Doesn’t change the model’s overall design—just a small tweak so each action in the chunk can have its own “time” setting.

- Can be added with only a few lines of code.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

The authors tested their method in both simulations and real-world tasks:

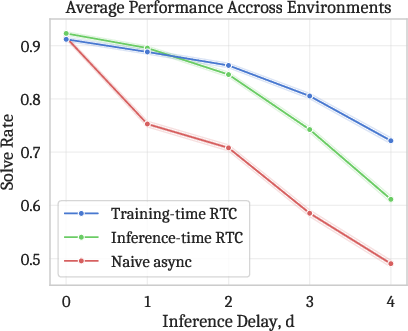

- Simulations: At higher delays (when the model takes longer to think), the training-time method performed better than the inference-time fix. This shows the model becomes more robust when taught about delays upfront.

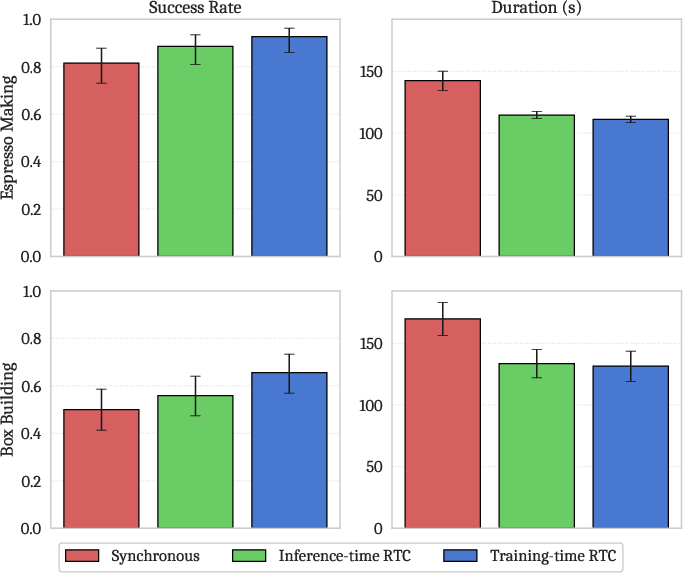

- Real-world tasks: They fine-tuned a strong base robot model (called π0.6) and tested on two complex, hands-on tasks:

- Building a cardboard box

- Making espresso (grinding, tamping, extracting, pouring)

Results:

- The training-time method matched the task success and speed of the inference-time method.

- It was also computationally cheaper during operation, reducing the robot’s run-time latency (for example, about 108 ms vs. 135 ms on average in one setup).

- Both real-time methods (old and new) were faster than a basic approach that waits for each chunk before moving (which causes visible pauses).

Why this matters:

- Robots can move smoothly and react quickly even with large, powerful AI models.

- It reduces the extra “thinking load” during operation, making real-time control more practical.

- It works on challenging, real-world tasks without redesigning the robot or the model.

Implications and Impact

This work suggests a simple, practical way to get smooth, real-time robot control using big models:

- It’s easy to adopt: a drop-in replacement with minimal code changes and no new hardware or major architecture changes.

- It’s efficient: less heavy computation when the robot is running, helping with speed and cost.

- It’s robust: handles bigger delays better because the model learned to expect them.

A small trade-off:

- The training-time method is less flexible than the inference-time fix—it focuses on a firm prefix that matches the delay, rather than softly blending extra overlapping actions.

- You need to choose and train on a range of expected delays to match your real-world setup.

Overall, this approach can make advanced robot controllers more reliable and responsive in everyday applications—like home assistance or industrial tasks—where reacting quickly and smoothly really matters.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to guide future research:

- Training–inference mismatch: the method trains with ground-truth (perfect) action prefixes but deploys with prefixes generated by the model’s prior chunk; the impact of this exposure bias and strategies like scheduled sampling, noisy/perturbed prefixes, or mixing predicted prefixes during training are not studied.

- Lack of “soft” conditioning: training-time RTC supports only hard prefix conditioning (exactly d actions) and cannot incorporate additional overlapping actions with graded weights as inference-time inpainting does; it is unclear how to recover these benefits without reintroducing inference-time overhead.

- Sensitivity to delay distribution: the approach requires selecting a training distribution over delays; robustness to mismatch between the trained delay distribution and real-world, nonstationary, or heavy-tailed latency profiles (including bursty/jittery delays) is not evaluated.

- Handling intra-chunk delay variability: real systems can experience delay jitter within a chunk; the method assumes a fixed prefix length d per generation and does not address robustness when d changes mid-generation or when the chunk completion time varies.

- Observation staleness: the method accounts for action delay via prefixes but does not explicitly model stale observations (o_t captured d steps earlier); how to integrate observation time-lag compensation (e.g., predictive state estimation) remains open.

- Theoretical guarantees: there is no analysis of continuity, jerk bounds, or closed-loop stability under asynchronous chunking with action prefixes; formal guarantees or control-theoretic analyses are missing.

- Error accumulation across chunks: the method’s robustness to compounding errors when conditioning on imperfect prefixes over many chunks (long horizons) is not measured or analyzed.

- Scalability to large delays: performance and stability for larger delays relative to horizon (d approaching H) and the trade-offs among prediction horizon H, execution horizon s, and delay d (beyond the feasibility constraint d ≤ H − s) are underexplored.

- Generality beyond flow matching: applicability to non-flow-matching policies (e.g., DDPM-style diffusion, autoregressive policies, model-predictive controllers) and to discrete or mixed action spaces is not demonstrated.

- Architectural generality: while termed a “drop-in replacement,” the method relies on per-token conditioning (per-token timestep in adaLN-zero); feasibility and performance on architectures where such conditioning is nontrivial (e.g., non-transformers, convolutional backbones, or quantized/edge models) are unclear.

- Combination methods: whether a hybrid approach (training-time conditioning plus lightweight inference-time correction) can recapture the advantages of soft masking without significant overhead is not investigated.

- Robustness to distribution shift: performance under unexpected dynamics, disturbances, occlusions, or adversarial perturbations in the real world is not evaluated.

- Broader evaluation: real-world results are limited to two tasks and a single robot/model family; generalization across diverse tasks, embodiments, environments, and datasets is not shown.

- Fair latency-controlled comparison: real-world comparisons report different average end-to-end latencies for training-time (≈108 ms) vs inference-time RTC (≈135 ms); equal-latency experiments are needed to isolate method effects from latency differences.

- Metrics beyond success and duration: effects on motion smoothness (e.g., jerk/acceleration), safety (torque/force limits), and user-perceived quality are not measured.

- Compute trade-offs: while inference-time overhead is reduced, the paper lacks a quantitative analysis of the train–infer compute trade-off (fine-tuning cost vs runtime savings), including energy and cost on edge vs server hardware.

- Denoising step ablations: the sensitivity of performance and latency to the number of denoising steps and alternative ODE/SDE solvers is not explored.

- Delay sampling policy: only simple distributions (uniform or exponentially weighted) are tried; optimal curricula, adaptive sampling, or online adjustment of training delays based on measured runtime latency remain open.

- Interaction with execution horizon: simulation ties s to max(d, 1); the impact of different s/H schedules, variable s, or adaptive execution horizons on performance and latency is not systematically analyzed.

- Integration with hierarchical control: compatibility with hierarchical VLAs (high-level planner + low-level controller), and how prefix conditioning interacts with low-level servo loops or impedance control, is untested.

- Effect on general skills and forgetting: fine-tuning with prefix conditioning may alter a base model’s broader capabilities; potential catastrophic forgetting or degradation on tasks not targeted during fine-tuning is not assessed.

- Handling missing/uncertain prefixes: resilience to dropped actions, partial prefixes, or uncertainty in d (e.g., using a belief over d) is not studied.

- Comparisons to concurrent methods: empirical head-to-head against A2C2, VLASH, or other lightweight correction methods is absent, leaving relative strengths and weaknesses unclear.

- Reproducibility and deployment details: results on on-device/edge hardware, network jitter impacts, memory/energy footprints, and full code/dataset availability for replication are not provided.

Glossary

- Action chunking: Representing control as sequences of short action segments predicted by a policy. "Action chunking \citep{zhao2023learning,chi2023diffusion} is the de facto standard in end-to-end imitation learning for visuomotor control."

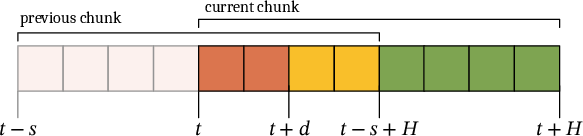

- Action postfix: The portion of an action chunk that follows the conditioned prefix and is produced by the model. "and is an action postfix (Figure~\ref{fig:diagram}, yellow and green),"

- Action prefix: The overlapping initial actions from the previous chunk used to condition the current generation under a delay. "We call these actions from the previous chunk that overlap with the current chunk the action prefix (see Figure~\ref{fig:diagram})."

- Asynchronous execution framework: An execution scheme where action generation overlaps with ongoing execution to reduce latency. "which introduces an asynchronous execution framework that serves as a foundation for this work."

- Conditional flow matching: A training objective that conditions a generative flow on observations to match the data distribution of action chunks. "We consider policies trained with conditional flow matching \citep{lipman2022flow}, which minimizes the following loss:"

- Controller timestep: A discrete time index of the robot control loop. "and indicates a controller timestep."

- Denoising steps: Iterations of the generative solver that progressively refine samples toward clean actions. "with 5 denoising steps, averaging 108ms of end-to-end latency for training-time RTC () and 135ms for inference-time RTC ()."

- Diffusion transformer: A transformer architecture used within diffusion/flow models for sequence denoising. "a standard diffusion transformer such as the \PiZeroSix{} action expert."

- Drop-in replacement: A method that can substitute an existing component without changes to interfaces or architectures. "and thus acts as a seamless drop-in replacement."

- Execution horizon: The number of actions from a chunk that are executed before the next chunk begins. "we roll out each chunk for timesteps, where is the execution horizon."

- Flow matching timestep: The scalar time parameter that indexes the generative flow during training/inference. "and denotes the flow matching timestep."

- Hierarchical VLA designs: Architectures that split a VLA into separate high-level (planning) and low-level (action) components. "employ hierarchical VLA designs where the model is split into a heavyweight System 2 (high-level planning) and lightweight System 1 (low-level action generation) component."

- Inference delay: The number of control steps between starting inference and the chunk becoming available. "we define the quantity to be the inference delay in units of controller timesteps."

- Inference latency: The total time taken to run model inference. "when the model inference latency is in the tens to hundreds of milliseconds"

- Inference-time inpainting: A technique that fills in parts of the output during inference by conditioning on known tokens. "Inference-time RTC \citep{black2025real} conditions the policy on the action prefix (Figure~\ref{fig:diagram}, red) using a inference-time inpainting method based on pseudoinverse guidance \citep{pokle2023training,song2023pseudoinverse}."

- Kinetix: A dynamic simulated manipulation benchmark used for evaluation. "our simulated experiments use the same dynamic Kinetix \citep{matthews2024kinetix} benchmark as RTC (see \citep{black2025real} for details)."

- MLP-Mixer: A neural architecture based on MLPs that mixes features across tokens and channels. "a 4-layer MLP-Mixer \citep{tolstikhin2021mlp} architecture"

- Mixture of expert policies: A dataset generation strategy combining multiple expert controllers to improve training diversity. "on data generated by a mixture of expert policies."

- Prediction horizon: The length of the action chunk predicted at each decision point. "We call the prediction horizon, and at inference time, we roll out each chunk for timesteps, where is the execution horizon."

- Pseudoinverse guidance: An inpainting guidance technique that uses a pseudoinverse to enforce constraints during denoising. "using a inference-time inpainting method based on pseudoinverse guidance \citep{pokle2023training,song2023pseudoinverse}."

- Real-time chunking (RTC): An asynchronous framework that predicts action chunks and conditions on committed actions to ensure continuity. "Real-time chunking (RTC) enables vision-language-action models (VLAs) to generate smooth, reactive robot trajectories by asynchronously predicting action chunks and conditioning on previously committed actions via inference-time inpainting."

- Soft masking: A conditioning scheme that weights overlapping actions beyond the prefix with decaying weights rather than hard constraints. "In RTC, this is referred to as ``soft masking''."

- System 1: The lightweight low-level action generation component in a hierarchical VLA. "System 1 (low-level action generation)"

- System 2: The heavyweight high-level planning component in a hierarchical VLA. "System 2 (high-level planning)"

- Vector-Jacobian product: A backpropagation operation computing products with the Jacobian to apply guidance during inference. "requires computing a vector-Jacobian product (using backpropagation) during each denoising step."

- Vision-language-action model (VLA): A model that integrates visual, language, and action modalities to produce robot control sequences. "vision-language-action models (VLAs) consisting of billions of parameters have increasingly been used to control robots at high frequencies to accomplish dexterous tasks."

- Vision-LLM (VLM): A multimodal model that processes vision and language; can be extended to output actions. "augmenting vision-LLMs (VLMs) to produce action chunks has demonstrated great success in robot manipulation, giving rise to vision-language-action models (VLAs)~\citep{rt22023arxiv,collaboration2023open,kim2024openvla,black2024pi,...}."

- Wilson score intervals: A statistical method for confidence intervals of proportions used in reporting success rates. "Each data point represents 2048 trials, and 95\% Wilson score intervals are shaded in."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below is a focused list of practical, deployable use cases that leverage training-time action conditioning (simulated inference delay, prefix-conditioned generation) as a drop-in replacement for inference-time inpainting in real-time robot control. Each item notes sector, the specific use case, likely tools/products/workflows, and key assumptions.

- Manufacturing and Assembly: Retrofit existing RTC-based VLA controllers (e.g., Pi0.6-like action experts) on assembly lines to remove inference-time inpainting overhead, reducing latency “jerks” and increasing throughput in tasks like fastening, insertion, and packaging; Tools/Workflows: minimal-code fine-tuning with prefix conditioning, ROS/ROS2 nodes that accept

dand prefix buffers, telemetry-driven delay sampling, H-s constraint checks; Assumptions/Dependencies: action chunking flow policies available, demonstration datasets exist, delays ≤ H − s, control frequency known, adaLN-zero or equivalent per-token conditioning supported. - Warehouse Logistics (Pick, Pack, Box Building): Increase cycle speed and reliability for pick-and-place, carton erection, and tape sealing by maintaining smooth inter-chunk continuity under cloud inference; Tools/Products: “RTC-TAC” fine-tuning pipeline on site data, cloud-edge deployment with measured latency histograms feeding training

dsampling, integrated monitoring (Wilson-score success metrics, per-chunk latency); Assumptions: stable network, remote GPU inference compatible, sufficient data for target tasks, execution horizon tuned to meet H − s. - Food & Beverage Automation (Espresso Kiosks, Cafeteria Stations): Deploy robots that perform grinding, tamping, extraction, pouring without pauses between action chunks, matching speed/performance of inference-time RTC while being computationally cheaper; Tools: safety wrappers for high-contact tasks, HMI for baristas/operators, fixed 50 Hz or comparable controllers, 5–8 denoising steps; Assumptions: camera placement and calibration stable, consistent task scripts, latency under supported delay range, quality demonstrations.

- Embedded Edge Robotics (Jetson Orin, Xavier, ARM SoCs): Achieve real-time control on lower-power hardware by avoiding inpainting vector-Jacobian products at inference, enabling higher control frequencies at the edge; Tools: quantization/pruning plus training-time RTC, dynamic denoising-step scheduling, latency histogram–guided

dsampling; Assumptions: diffusion-transformer-like policy supports per-token timestep, adequate memory bandwidth, continuous control actions. - Teleoperation and Shared Autonomy: Improve robustness to variable network latency in human-in-the-loop control by training with sampled delays reflective of empirical latency distributions; Tools: “Latency-aware policy training” that logs end-to-end latency (including network and robot runtime), online selection of execution horizon s, prefix buffer alignment; Assumptions: human demonstrations aligned to action chunks, reliable latency telemetry, delays ≤ H − s.

- Software/ML Tooling for VLA Frameworks: Integrate prefix-conditioned training modules into existing PyTorch/JAX codebases as a plug-in replacement for pseudoinverse guidance; Tools: open-source training wrapper implementing per-token timesteps and postfix-only loss masking, dataset augmentation scripts to pad prefixes and simulate

d, unit/integration tests against RTC baselines; Assumptions: willingness to fine-tune existing models, access to training compute, MLOps pipelines for deployment. - Academic Research and Benchmarking: Use the Kinetix dynamic benchmark (or equivalent) to paper latency-resilience and action-prefix conditioning in flow policies; Tools: reproducible scripts for delay sampling (uniform or exponentially weighted), reporting with Wilson score intervals, ablation of delay distributions; Assumptions: access to GPU resources and standardized datasets, matched training compute across baselines.

- Energy/Power Budgeting for Mobile Robots: Reduce inference compute and power consumption (battery life gains) by removing inpainting overhead during high-frequency control tasks; Tools: power monitoring and budgeting dashboards, adaptive denoising-step schedules; Assumptions: measurable power savings relative to pseudoinverse guidance, stable ambient compute/thermal conditions.

- Policy and Procurement in Public-Space Robotics: Specify latency-aware training as a preferred practice in RFPs for robots operating near people (retail, airports), to minimize pauses and jerks that affect user safety and perception; Tools: conformance testing harnesses that simulate representative delay distributions and verify smoothness across chunk boundaries; Assumptions: procurement bodies recognize latency as a safety/performance factor, standardized test procedures.

- Consumer/Home Robotics (Daily Life): Update firmware for household robots (dish loading, tidying, simple kitchen tasks) to improve reaction smoothness and user experience with variable home network conditions; Tools: fine-tuning with household demonstration data, privacy-preserving telemetry for latency distributions, edge-first deployment; Assumptions: demonstration coverage of target tasks, controller frequency adequate, H − s constraint satisfied.

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities will likely require further research, scaling, integration with other modules, or regulatory work before broad deployment.

- Healthcare and Assistive Robotics: Apply prefix-conditioned, latency-aware control to delicate tasks (feeding assistance, medication handling) where pauses or jerks are unacceptable; Tools/Workflows: clinical-grade data collection, safety certification, formal verification of bounded delay behavior; Assumptions/Dependencies: regulatory approval (FDA/CE), comprehensive safety envelopes, robust sensing and redundancy.

- Autonomous Vehicle Manipulation (Charging Arms, Cargo Handling): Use training-time RTC for precise real-time manipulation in AV ecosystems (robotic charging connectors, loading/unloading); Tools: integration with hierarchical VLAs for planning + low-level control, industrial-grade sensing; Assumptions: stringent safety requirements, nonstationary environments, coordinated scheduling with AV stacks.

- Hybrid Conditioning with Correction Heads (A2C2) or Future-Action Conditioning (VLASH): Combine training-time conditioning with lightweight correction heads or future-action conditioning to get the flexibility of soft masking and the speed of training-time methods; Tools: hybrid architectures that support both hard-prefix and soft-overlap conditioning; Assumptions: additional research on blending guidance signals, careful stability analysis.

- Standards and Benchmarks for Latency-Aware Robot Learning: Establish community benchmarks and best practices around delay distributions, H, s selection, and reporting; Tools: consortium-driven test suites, shared datasets with recorded latency traces; Assumptions: cross-institution coordination, open data policies.

- Adaptive, Self-Tuning Delay Curriculum: Develop controllers that estimate latency online and adapt the effective

dand execution horizon s, with training-time curricula that match deployment telemetry; Tools: closed-loop telemetry pipelines, on-robot adaptation of denoising steps; Assumptions: robust online estimation, safety constraints for adaptation. - Smaller, Edge-First VLAs (SmolVLA/MiniVLA + Training-Time RTC): Combine compact architectures with prefix-conditioned training to meet 50–100 Hz control on low-power chips for consumer robots; Tools: co-design of model size, control horizons, and delay sampling, hardware-aware training schedules; Assumptions: mature compact VLA designs, tight integration with edge accelerators.

- Industrial Process Control Beyond Robotics: Apply chunked, prefix-conditioned control to CNC trajectory smoothing, additive manufacturing path planning, and PLC-driven actuation where inference delays disrupt smooth operation; Tools: middleware bridging RTC-TAC to PLCs/industrial protocols, data collection pipelines for action chunks; Assumptions: mapping from robotic action chunks to discrete process controls, high-quality trajectory datasets.

- Education and Workforce Training: Create curricula and lab modules teaching latency-aware design, delay distributions, and real-time chunking for robotics programs; Tools: classroom kits with sample datasets and training scripts, exercises on H − s constraints and delay sampling strategies; Assumptions: institutional adoption, resource availability.

- Regulatory Guidance on Latency Budgets and Real-Time Safety: Develop guidelines that quantify acceptable delay ranges and require latency-aware training/testing for robots in public spaces; Tools: compliance checklists and standardized smoothness metrics; Assumptions: policy momentum and stakeholder buy-in.

Cross-Cutting Assumptions and Dependencies

- Action chunking flow policies are available, with access to demonstration data covering target tasks and environments.

- Controllers satisfy the constraint d ≤ H − s for valid action prefixes; s and H are selected based on task and hardware.

- Policies support per-token timesteps (e.g., adaLN-zero conditioning) and postfix-only loss masking without architecture changes.

- Delay distributions used for training reflect deployment telemetry; robustness depends on sampling strategy and coverage.

- Safety wrappers, monitoring, and fallback strategies are in place for contact-rich or safety-critical tasks.

- Deployment compute (edge or cloud) and networking are sufficiently stable to stay within supported delay ranges.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.