On the Computability of Artificial General Intelligence (2512.05212v1)

Abstract: In recent years we observed rapid and significant advancements in artificial intelligence (A.I.). So much so that many wonder how close humanity is to developing an A.I. model that can achieve human level of intelligence, also known as artificial general intelligence (A.G.I.). In this work we look at this question and we attempt to define the upper bounds, not just of A.I., but rather of any machine-computable process (a.k.a. an algorithm). To answer this question however, one must first precisely define A.G.I. We borrow prior work's definition of A.G.I. [1] that best describes the sentiment of the term, as used by the leading developers of A.I. That is, the ability to be creative and innovate in some field of study in a way that unlocks new and previously unknown functional capabilities in that field. Based on this definition we draw new bounds on the limits of computation. We formally prove that no algorithm can demonstrate new functional capabilities that were not already present in the initial algorithm itself. Therefore, no algorithm (and thus no A.I. model) can be truly creative in any field of study, whether that is science, engineering, art, sports, etc. In contrast, A.I. models can demonstrate existing functional capabilities, as well as combinations and permutations of existing functional capabilities. We conclude this work by discussing the implications of this proof both as it regards to the future of A.I. development, as well as to what it means for the origins of human intelligence.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

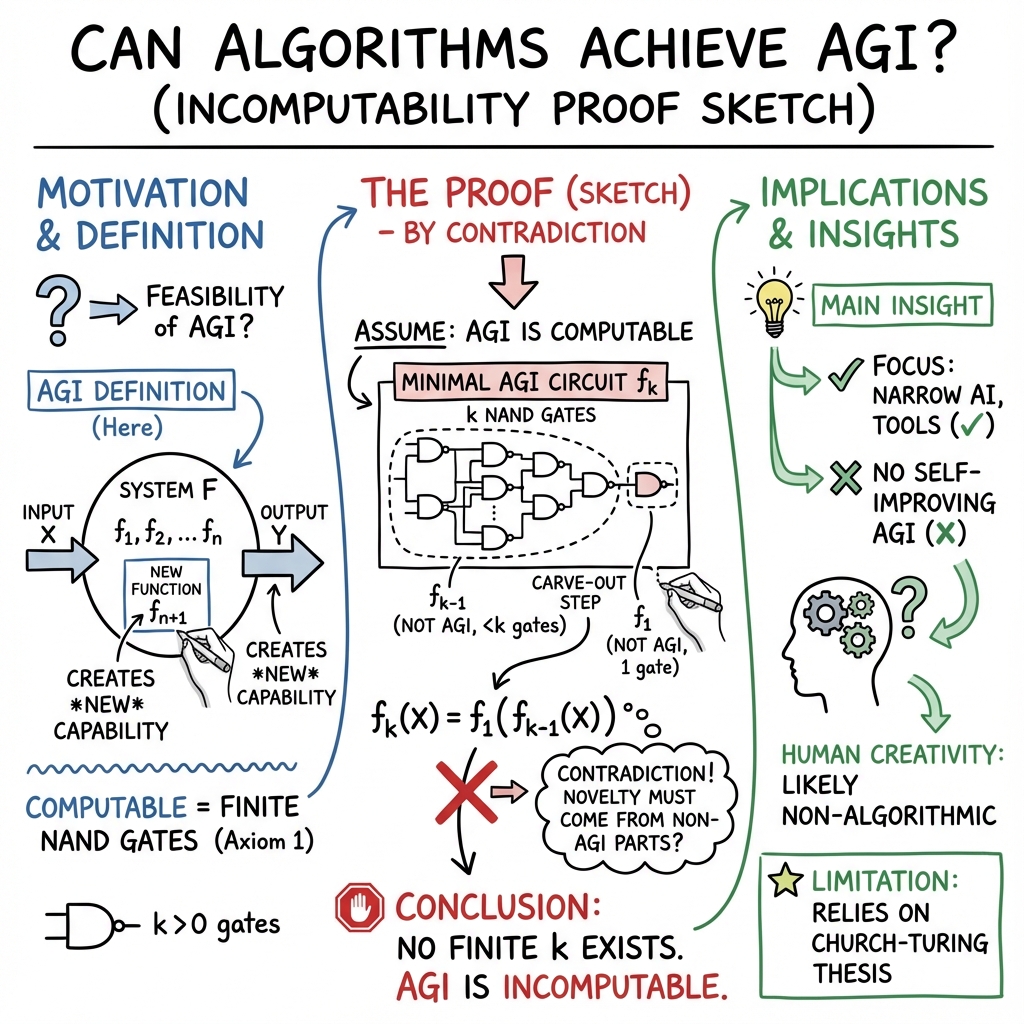

This paper asks a big question: Can a computer or AI ever be truly creative like a human and invent brand‑new abilities? The authors define “Artificial General Intelligence” (AGI) as a machine that can create new ways of doing things (new functions) that weren’t already inside it. Then they argue, using ideas from computer science, that no algorithm (no step‑by‑step computer program) can do that. In short, they claim AGI (as they define it) is impossible to compute.

Key Questions

The paper focuses on two simple questions:

- What exactly does “AGI” mean?

- If AGI means creating genuinely new abilities, can any algorithm or computer actually do that?

How They Approach the Problem

Think of an algorithm like a recipe: it follows steps to turn inputs (ingredients) into outputs (a finished dish).

To study what algorithms can and cannot do, the authors use two classic computer science ideas:

- The Church–Turing Thesis: This says that anything you can calculate using clear, mechanical steps (an “effective method”) can be done by a very simple imaginary computer called a Turing Machine. Modern computers are basically the same in power.

- Boolean logic and NAND gates: These are the tiny building blocks of digital computers. A NAND gate is like a basic Lego block for logic—it can be combined to build every other kind of logic part and, in theory, entire computers.

Their key setup:

- If a process is computable, you can build it using a finite number of NAND gates. If you cannot build it with any finite number of NAND gates, then it’s not computable.

- They define AGI as a system that can generate a brand‑new function (new ability) that wasn’t already in its set of abilities. In everyday terms: the system can do something genuinely new that wasn’t pre‑built or learned from training data.

The Main Proof Idea (in everyday terms)

- Start simple: A single wire or a single NAND gate can’t “invent” new abilities. They only do what they were built to do.

- Build up: Combine many NAND gates to make more complex circuits (like building with more Lego blocks).

- Suppose, for the sake of argument, there exists a smallest possible “AGI machine” built from k NAND gates that can create a truly new function.

- Now split that k‑gate machine into two parts: one part with k‑1 gates, and the other part with just 1 gate.

- If the whole machine is truly creative, then the new ability must come from one of those parts. But the k‑1 part and the 1‑gate part use fewer than k gates, and (by the “smallest machine” assumption) neither can be AGI.

- That’s a contradiction. So there cannot be any smallest k‑gate AGI machine—and in fact, there is no finite number k that makes AGI possible.

- Conclusion: AGI (defined as creating new functions) is not computable.

A helpful analogy: If you only have Lego bricks of certain shapes, you can stack and rearrange them in endless ways, but you can’t magically create a brand‑new brick shape you didn’t have. The system can combine and permute existing abilities, but it can’t invent a genuinely new ability out of nothing.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

Here are the paper’s main claims:

- No algorithm can create truly new functional capabilities beyond what it already contains.

- Therefore, AGI—defined as creativity that produces new functions not present in the system—is incomputable (you cannot build it on any standard computer).

- AI can still be very powerful: it can demonstrate and recombine existing capabilities in impressive ways. But it cannot cross the line into true creativity as defined here.

Why this matters:

- It challenges the common idea that computers will one day be creatively intelligent like humans.

- It suggests we should focus AI on specific tasks (where it already excels) rather than expect it to replace human creativity.

Methods and Technical Terms Explained Simply

- Algorithm: A recipe or set of steps a computer follows.

- Turing Machine: A very simple, imaginary computer model that defines what “computable” means.

- Church–Turing Thesis: The belief that anything you can do with a clear, mechanical method, a Turing Machine (and thus modern computers) can also do.

- NAND gate: A tiny logic part that can be combined to build any computation. Think Lego blocks for building computers.

- Computable: You can do it step‑by‑step in a finite time with a computer built from basic parts (like a finite number of NAND gates).

The authors use a “proof by contradiction”: they assume an AGI machine exists, and then show that assumption leads to a logical conflict when you decompose the machine into simpler parts—so the original assumption must be false.

Implications and Impact

This research has several practical takeaways:

- For AI development: It suggests focusing on “narrow AI” (systems designed for specific jobs, like medical imaging or self‑driving) rather than expecting a single, general system to invent new science or art.

- For AI safety debates: It reduces fears that an all‑powerful, self‑directed AGI will emerge and take over. The paper argues such creativity is not computable.

- For understanding human intelligence: If human general intelligence involves true creativity (new functions), then it might not be computable by machines. That raises deep questions about how human minds work and whether some parts of intelligence are non‑algorithmic or rely on physical processes beyond current computing models.

Limits of the Paper’s Argument

The proof relies on the Church–Turing Thesis, which is widely accepted but not formally proven. If one day someone builds a “hypercomputer” (a device that can compute beyond Turing Machines), the conclusions could change. However, with today’s understanding, no known computer model can compute the kind of creativity defined as AGI in this paper.

Conclusion

In plain language: The paper argues that computers can rearrange and combine what they already know, but they can’t invent genuinely new abilities from scratch. So, under this definition of AGI, true machine creativity isn’t something algorithms can do. AI will remain extremely useful—just not creative in the same way humans are.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, concrete list of knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions left unresolved by the paper. Each point is framed to be actionable for future research.

- The paper’s AGI definition hinges on “creating new functionality not present in the initial system,” but it lacks a rigorous mathematical formalization of “functionality,” the set F, and what it means for a function to be “present” versus “generated,” especially for systems that learn, self-modify, or synthesize code.

- Axiom 1 equates computability with implementability via a finite number of NAND gates configured as a (seemingly) combinational circuit; it does not formally account for sequential circuits, state, unbounded memory, or time-varying reconfiguration—core aspects of Turing-computable processes. A formal extension to sequential/stateful architectures is needed.

- The proof’s “carve-out” step assumes that if a k-gate system is AGI, then the new functionality must be attributable to either the (k–1)-gate subcircuit or the 1-gate subcircuit; the paper does not provide a formal argument that composition of non-AGI components cannot yield AGI at the system level (emergence under composition remains unaddressed).

- The existence and uniqueness of a “minimum AGI system” (with the least k) is asserted via Lemma 4 but not rigorously proven. A formal existence proof (e.g., via well-ordering on gate counts across circuit families parameterized by input size and state) is required if the contradiction hinges on such minimality.

- The argument treats the algorithm as a fixed circuit with a fixed gate count and topology; it does not analyze algorithms that reconfigure themselves over time (e.g., neural architecture search, JIT compilation, dynamic programming synthesis, or self-modifying code). A formal model of dynamic topology and its implications for “new functionality” is missing.

- The paper requires algorithms to be deterministic and terminating for all valid inputs, omitting probabilistic or partial computability (non-terminating on some inputs). An extension that explicitly covers randomized Turing machines and partial recursive functions is needed to establish whether “creativity” remains incomputable under these more general models.

- The boundaries between “training” and “inference” are not formalized. For learning systems, it is unclear whether training is considered part of the algorithm, how the “initial” functionality set F is defined pre- and post-training, and how online learning or continual learning affects the claim.

- Program synthesis is treated implicitly as “no new functionality” because it is produced by a prior algorithm, but the paper does not formally address whether generated code that implements previously unknown behaviors (to the designers) constitutes “new functionality” under Definition 1.

- The mapping from “new scientific knowledge” to the function-level criterion f(X)=Y is insufficiently specified. There is no operational metric or test to decide when an output Y constitutes “new functionality” relative to F (e.g., using algorithmic information theory, semantic novelty tests, or formal verification against extant knowledge bases).

- The reliance on NAND-gate universality does not address computational models with continuous variables or real-number computation (e.g., analog computation, Blum–Shub–Smale model) where “computability” may differ; the paper does not analyze whether its conclusion holds in these models.

- The Physical Church–Turing discussion raises the possibility of hypercomputation (HTMs) but provides no formal criteria, constructive models, or physical feasibility constraints to assess whether AGI-like “new functionality creation” could be realized outside Turing computability.

- The proof does not consider interaction with external tools, APIs, or environments that enable systems to acquire capabilities during runtime (tool use, delegation, external theorem provers). The boundary conditions for what is “coded” versus “externally sourced” functionality need to be formally defined.

- The paper introduces “new functionality” as a single mapping required to produce output Y for input X but does not address multi-step processes where intermediate decision-making, planning, and tool use collectively realize capabilities beyond any single component’s function. A formal multi-process capability model is needed.

- The assumption that “no algorithm can demonstrate new functional capabilities not already present in the initial algorithm itself” is claimed via the presented proof, but the argument does not engage with existing theory on computational creativity (e.g., novelty search, open-endedness) and does not offer counterexamples or formal impossibility results in those frameworks.

- The treatment of “emergence” is limited to gate composition; there is no analysis of emergent behavior in complex adaptive systems, distributed multi-agent systems, or learning dynamics, where capabilities can arise from interactions over time without being reducible to fixed subcomponents.

- The paper’s conclusion that human GI is incomputable (and possibly non-physical or non-computing physical) is speculative; it lacks testable predictions, neuroscientific correlates, or empirical methodologies to differentiate computable versus incomputable cognitive processes in humans.

- The suggestion that human GI cannot be the product of an algorithmic evolutionary process is not supported by a formal model of evolution’s computational properties; a precise analysis of whether evolutionary dynamics can implement incomputable processes is needed.

- No empirical falsification strategy is proposed: there are no benchmarks, protocols, or experiments that could demonstrate (or refute) “new functionality” creation by advanced AI systems according to Definition 1. Designing such tests is an open methodological gap.

- The dependency on the Church–Turing Thesis is acknowledged but not mitigated: the paper does not explore alternative proof strategies that would stand even if the thesis were refined (e.g., via “effective computability” formalizations, resource-bounded models, or axiomatizations of creativity).

- The proof does not explicitly handle circuit families indexed by input length (non-uniform computation) or complexity classes where capability depends on input size, resources, or advice strings; whether the incomputability claim persists under non-uniform models remains open.

- The paper does not address whether “new functionality” could be defined relative to a knowledge base rather than the algorithm’s internal function set, nor does it examine how external validation (e.g., peer review in science) would formally integrate into the computability claim.

- Reference coverage is limited regarding formal models of creativity and open-endedness in computation; integrating and testing the paper’s claims against those literatures (e.g., algorithmic information theory, artificial life) is an open task.

Glossary

- Artificial General Intelligence (A.G.I.): A proposed machine intelligence matching human general intelligence, defined here as the ability to generate genuinely new functionality and knowledge not present in the original system. "Or more formally, can machines achieve Artificial General Intelligence (A.G.I.)?"

- Bold Physical CT: The strong form of the Physical Church–Turing thesis asserting that all physical processes are computable by Turing machines. "G. Piccinini [55] expands on the computability of physical processes and argues that not all physical processes can be considered physical systems... the 'Bold Physical CT' and a more relaxed 'Modest Physical CT'."

- Church-Turing Thesis: The hypothesis that any effectively computable function can be computed by a Turing machine. "Today the work of Church and Turing is widely described as the Church-Turing Thesis [39], which is a hypothesis about the nature of computation."

- Entropy divergence: An author-coined notion suggesting that a truly thinking system raises new questions that increase entropy after receiving information. "The author refers to that phenomenon as entropy divergence."

- Gödel's incompleteness theorem: The result that any sufficiently powerful formal system is incomplete, containing true statements that cannot be proved within the system. "Similar arguments are made by M. M. Schlereth [62] that also uses Gödel's incompleteness theorem [60] and Kolmogorov complexity [61] to argue that no truly general A.G.I. algorithm is possible."

- Halting Problem: The undecidable problem of determining whether a given program will eventually halt on an input. "One famous such example is the Halting Problem were asking if an algorithm (or Turing Machine) ever halts is an undecidable problem as proved by Alan Turing [38]."

- Hyper-Turing Machine (HTM): A hypothetical computational model that can compute functions beyond Turing machine capabilities. "there must be some Hyper-Turing Machine (HTM), with novel computation mechanisms, that can compute such methods that a Turing Machine cannot."

- Kolmogorov complexity: The length of the shortest program that produces a given string; used to show limits of universal optimal algorithms. "Kolmogorov complexity proves that no general algorithm that provides optimal solution for all problems can ever be conceived."

- LLMs: Neural network models trained on vast text corpora to process and generate natural-language outputs. "Generative A.I. leverages LLMs that can process queries described in natural language [10, 11]."

- Modest Physical CT: The weaker form of the Physical Church–Turing thesis stating that only physical processes that are computing systems are Turing-computable. "the Modest Physical CT argues that only physical processes that represent compute systems (a.k.a. physical functions) can be computed by Turing machines."

- Physical Church-Turing thesis (Physical CT): The claim relating physical processes and devices to Turing-machine computability. "The Physical Church-Turing thesis (Physical CT) [54] links mathematical notions to the physical world, associating physical (mechanical, digital or quantum) computing devices with the theoretical concept of a Turing machine."

- Rice's theorem: The theorem that all non-trivial semantic properties of programs/Turing machines are undecidable. "He also uses Rice's theorem [63], to argue that many aspects of complex systems are known to be incomputable, and thus A.G.I. may also be incomputable."

- Shannon entropy: A measure of the uncertainty or information content of a random variable/message. "Shannon's entropy, when describing information, does not refer to the actual meaning (e.g., knowledge or functionality) contained in a message but rather the maximum theoretical information that a message could potentially transmit, even if in practice a message has no real meaning (e.g., it contains only gibberish)."

- Turing Machine: An abstract computational model that formalizes algorithmic computation via a tape and deterministic state transitions. "calculated by a Turing machine [40], an abstract machine that at any given moment, its behavior can be completely determined by its current state and inputs."

- Turing completeness: The property of a system being able to compute any computable function by simulating a Turing machine. "Thus, according to the Church- Turing Thesis, modern computers are able to compute all computable processes (given enough memory and time), a concept known as Turing completeness."

- Universal gate: A logic gate from which all other logic functions can be built (e.g., NAND or NOR). "That is why the NAND gate (as well as the NOR gate) is also referred to as a universal gate."

- Universal Turing Machine (UTM): A Turing machine capable of simulating any other Turing machine via a program/input encoding. "A. Turing introduced the Universal Turing Machine (UTM) [40], a machine that can compute any other Turing Machine."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now by redirecting strategy, updating governance, and building tools that leverage the paper’s core finding: under the Church–Turing framework and the paper’s creativity definition, algorithmic systems can recombine and permute existing functionality but cannot originate genuinely new functionality.

- Composable narrow-AI product strategy across sectors (software, robotics, healthcare, finance, education)

- Use case: Replace “general-purpose AGI” roadmaps with a portfolio of specialized models orchestrated via a capability router (e.g., task-specific planners, domain retrievers, validation modules).

- Tools/products/workflows: “Capability registry” (catalog of vetted model functions), “Model orchestrator” microservice layer, formal specs for each model’s operational design domain (ODD).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to domain datasets; acceptance of the paper’s AGI definition; engineering resources for integration; clear performance metrics per task.

- AI governance and marketing compliance (industry, policy, consumer protection)

- Use case: Establish internal review boards that prohibit “AGI” claims and require accuracy in capability statements; add standardized disclaimers about limits (no genuine novelty creation).

- Tools/products/workflows: “AGI claim review checklist,” template disclosures (“model outputs are recombinations of existing functionality/data”).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory alignment; legal counsel; organizational buy-in.

- Safety and risk management reprioritization (policy, security, platforms)

- Use case: Shift AI risk frameworks away from speculative runaway agency toward concrete harms (misuse, bias, privacy violations, fraud, disinformation, over-trust).

- Tools/products/workflows: Updated threat models; misuse monitoring; bias audits; privacy-by-design guidelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Revised safety budgets; cross-functional training.

- Procurement and vendor due diligence (enterprise IT, government)

- Use case: Require vendors to supply “functionality provenance reports” showing how outputs trace to training/data/code; evaluate claims of novelty with reproducible evidence.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Provenance auditor” pipelines; dataset lineage documentation; reproducible evaluation harnesses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Vendor transparency; data access; audit standards.

- Benchmarking and evaluation aligned to “creativity as new functionality” (academia, AI labs)

- Use case: Adopt tests that operationalize the paper’s AGI threshold (e.g., [1]) to check whether outputs require functionality not present initially; emphasize generalization within known capability sets.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Functionality novelty benchmarks,” differential capability maps, testbeds that separate recombination from true novelty.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Shared definitions; curated benchmark suites; reproducible training footprints.

- Human-in-the-loop innovation pipelines (academia, biopharma, materials science)

- Use case: Use LLMs for literature synthesis, hypothesis enumeration, and experiment planning; reserve hypothesis origination and theory formation to human experts.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Innovation kanban” with gates (synthesis → human hypothesis → computational screening → experimental validation).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Skilled domain scientists; data access; lab infrastructure.

- Education and AI literacy (K–12, higher ed, professional training)

- Use case: Integrate modules on computability, the Church–Turing thesis, and the paper’s creativity limits into AI curricula to reduce over-trust and hype.

- Tools/products/workflows: “AI Skepticism 101” courseware; case studies of recombination vs genuine novelty; classroom exercises mapping outputs to known functionality.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Curriculum approval; educator training.

- IP and legal policy adjustments (patent offices, courts, corporate legal)

- Use case: Update guidance that treats AI outputs as derivative/combinatorial unless human-origin novelty is established; require provenance in patent applications involving AI-assisted invention.

- Tools/products/workflows: “AI-derivation checks,” provenance documentation standards, examiner training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legislative/Judicial processes; consensus on novelty standards and the paper’s AGI definition.

- Safety-critical product design constraints (autonomous vehicles, medical devices, industrial automation)

- Use case: Formally constrain autonomy; certify models only within specified ODDs; enforce rule-based fail-safes and human oversight for out-of-ODD scenarios.

- Tools/products/workflows: ODD gating; formal verification of bounded capabilities; escalation to human supervisor.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sector standards; verification tooling; regulatory compliance pathways.

- Finance and investment portfolio realignment (VC, PE, corporate strategy)

- Use case: Screen out “AGI moonshots” predicated on new-functionality creation; prioritize narrow-AI ventures with measurable task ROI and defensible data moats.

- Tools/products/workflows: “AGI hype risk” rubric; due diligence checklists focusing on task specification and evidence of generalization within known capabilities.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Investor acceptance; access to technical diligence.

- Content platforms and daily-life transparency (consumer apps, media)

- Use case: Attach “AI Info Cards” to outputs explaining model limitations and provenance; discourage treating AI as an oracle for life advice or metaphysical claims.

- Tools/products/workflows: UI components for disclosures; links to source material; flags for uncertainty.

- Assumptions/dependencies: UX resources; policy mandates; user testing.

- Research reproducibility and documentation (academia, open-source)

- Use case: Archive initial functionality sets (training data summaries, architecture specs) with publications to enable evaluation of recombination vs novelty claims.

- Tools/products/workflows: Data governance policies; model cards with functionality inventories; reproducibility repositories.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Willingness to share; privacy constraints; storage infrastructure.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, consensus-building, or new scientific/technical capabilities and may reshape standards, science policy, and foundational research programs.

- Formal “AGI Impossibility” standards and certification (standards bodies, regulators)

- Use case: Create a certification scheme that audits products against the paper’s AGI definition and prohibits misleading “AGI” labels in the marketplace.

- Tools/products/workflows: Standardized test suites; certification audits; compliance seals.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder consensus on definitions; regulatory adoption.

- Hypercomputation research programs (academia: CS, physics, philosophy of computation)

- Use case: Explore Hyper-Turing Machine concepts and physical mechanisms that could exceed Turing computability (if any), with clear impossibility/feasibility criteria.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Hyper-Turing lab” initiatives; theoretical models; experimental proposals (oracles, non-classical computation).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Significant theoretical breakthroughs; funding; acceptance that the Church–Turing thesis might be bounded.

- Physical Church–Turing empirical studies of human GI (neuroscience, cognitive science, philosophy of mind)

- Use case: Design experiments to test whether aspects of human general intelligence involve non-computing physical processes or phenomena not emulable by Turing machines.

- Tools/products/workflows: Neurophysiological assays for creativity markers; task paradigms isolating novel-functionality generation; cross-disciplinary collaboration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ethical approvals; measurement methodologies; clear operationalization of “new functionality.”

- Mature functionality-provenance engines (enterprise software, research infrastructure)

- Use case: Build systems that robustly infer whether model outputs are derivable by known functionality sets and trace them to training sources, improving trust and compliance.

- Tools/products/workflows: Corpus indexing at scale; semantic lineage graphs; proof-of-derivability inference.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to training data; scalable indexing; privacy-preserving provenance.

- Regulatory codification of AI terminology and claims (policy, law)

- Use case: Enact “Truth-in-AI advertising” laws defining AGI, mandating capability disclosures, and penalizing deceptive claims.

- Tools/products/workflows: Legal definitions; enforcement mechanisms; public registries of certified capabilities.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legislative cycles; stakeholder input; international harmonization.

- Composable AI operating systems (software ecosystems)

- Use case: Develop an OS-like layer that natively orchestrates many narrow models with formal specifications, capability negotiation, and fail-safe dispatch.

- Tools/products/workflows: Capability negotiation protocols; formal task contracts; runtime verifiers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Ecosystem buy-in; interoperability standards; performance/scaling engineering.

- Sector-specific “Non-AGI Safety Certification” frameworks (healthcare, robotics, energy)

- Use case: Standards that certify bounded capability, ODD adherence, human oversight, and provenance transparency in critical systems.

- Tools/products/workflows: Safety cases; conformity assessment; continuous monitoring requirements.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Standards bodies engagement; pilot programs; post-market surveillance.

- Education standards integrating computability and AI limits (national curricula, accreditation)

- Use case: Institutionalize modules on computability theory, AGI definitions, and ethical implications in STEM education.

- Tools/products/workflows: Curriculum frameworks; teacher training; assessment rubrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accreditation processes; teacher capacity; resource allocation.

- IP law reform on AI-assisted invention (policy, courts)

- Use case: Define a “human-origin innovation test” for patentability and clarify copyright for AI-generated content as derivative unless human novelty is demonstrated.

- Tools/products/workflows: Examination guidelines; evidentiary standards for human contribution; litigation frameworks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Jurisdictional harmonization; legal scholarship; public consultation.

- Cultural and public-health shifts in AI trust (daily life, mental health)

- Use case: Broad campaigns to normalize AI as powerful assistants for information synthesis rather than sources of novel truth; embed mental-health safeguards in AI companions.

- Tools/products/workflows: Public-service messaging; in-app safety prompts; referral pathways for vulnerable users.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Collaboration with health agencies; platform cooperation; evidence-based messaging.

Notes on Core Assumptions and Dependencies

- Most applications rely on the paper’s specific AGI definition (creativity = generation of new functionality not present initially) and the Church–Turing framing that underpins the incomputability claim.

- Feasibility of provenance-based tools depends on access to training data, logs, and model internals—often constrained by privacy, IP, or proprietary concerns.

- Policy and legal reforms require multi-stakeholder consensus and legislative timelines; interim voluntary standards may be prudent.

- If future work meaningfully challenges the Church–Turing thesis (or the paper’s definition), long-term applications tied to impossibility or hypercomputation will need reassessment.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.