Reversing Large Language Models for Efficient Training and Fine-Tuning (2512.02056v1)

Abstract: LLMs are known for their expensive and time-consuming training. Thus, oftentimes, LLMs are fine-tuned to address a specific task, given the pretrained weights of a pre-trained LLM considered a foundation model. In this work, we introduce memory-efficient, reversible architectures for LLMs, inspired by symmetric and symplectic differential equations, and investigate their theoretical properties. Different from standard, baseline architectures that store all intermediate activations, the proposed models use time-reversible dynamics to retrieve hidden states during backpropagation, relieving the need to store activations. This property allows for a drastic reduction in memory consumption, allowing for the processing of larger batch sizes for the same available memory, thereby offering improved throughput. In addition, we propose an efficient method for converting existing, non-reversible LLMs into reversible architectures through fine-tuning, rendering our approach practical for exploiting existing pre-trained models. Our results show comparable or improved performance on several datasets and benchmarks, on several LLMs, building a scalable and efficient path towards reducing the memory and computational costs associated with both training from scratch and fine-tuning of LLMs.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about making LLMs easier and faster to train by using “reversible” designs. Think of a reversible model like a movie you can play forward and backward perfectly: if you know the current frame, you can recover the previous one exactly. The authors borrow ideas from physics (where many systems are reversible) to build LLMs that don’t have to remember every step during training. This saves a lot of computer memory, lets you use bigger batches of data, and can speed up training—without hurting accuracy. They also show how to turn existing non-reversible models into reversible ones with light fine-tuning.

What questions does the paper try to answer?

- Can we design LLMs that use much less memory during training by making them reversible?

- Will these reversible models still work as well—or even better—than standard models?

- Can we convert popular, already-trained models into reversible versions with minimal effort?

- What math and design rules make reversible models stable and reliable?

How did they approach the problem?

To explain their approach, it helps to know a few common terms in simple language:

- Token: a small chunk of text (like a word or subword) the model reads.

- Embedding: turning tokens into numbers the model understands.

- Transformer layer: a building block that mixes information using attention and simple neural networks (MLPs).

- Backpropagation: the process used to learn; it usually needs you to keep all intermediate steps in memory.

Standard transformers “stack” layers and must store every layer’s output during training to compute gradients. That’s what eats up memory. The authors change the layer updates so each step can be perfectly undone. During training, instead of storing all steps, they reconstruct them on the fly when needed. They explore three reversible designs:

- Midpoint update: a step rule that lets you compute the next and recover the previous from the current—like taking a balanced step forward that you can always undo.

- Leapfrog update: a two-step rule inspired by wave motion; it’s stable and also reversible, good for passing information over many layers without “fading.”

- Hamiltonian update: keeps two states (like position and momentum in physics) that take turns updating each other. It conserves a kind of “energy,” helping the model stay stable and reversible.

They also show a practical recipe to retrofit (convert) existing, non-reversible models:

- Estimate the previous layer’s state from the current one.

- Use a reversible update that closely imitates the original model’s behavior.

- Fine-tune a little so the converted model’s outputs match the original model’s outputs.

Finally, they analyze the math behind these updates to make sure the models are stable (won’t explode or collapse) both forward and backward.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

In experiments on several models (like GPT-2 small and large, TinyLlama, and SmolLM2), they found:

- Similar or better accuracy: Reversible models matched or sometimes beat standard transformers on training/validation loss and zero-shot tasks (like PIQA, ARC, WinoGrande).

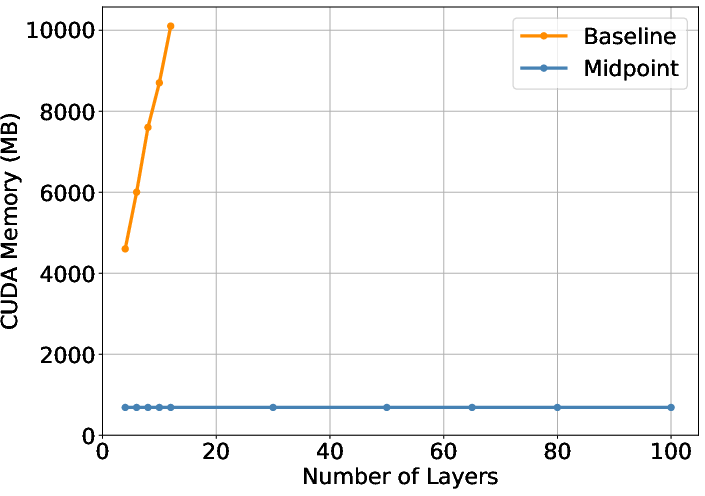

- Huge memory savings: Because reversible models don’t store every layer’s activations, they could fit batch sizes about 10 times larger on the same GPUs.

- Faster training in practice: Even though you recompute some steps, the bigger batch sizes often increase overall throughput (examples processed per second). In deeper models they saw up to about double the throughput compared to the baseline.

- Easy conversion: They successfully turned existing models (like TinyLlama and SmolLM2) into reversible versions with small amounts of fine-tuning. The converted models stayed very close in performance to the originals on benchmarks (for example, MMLU scores were almost the same).

Why this matters:

- Training large models is often limited by GPU memory. Reversible designs remove the biggest bottleneck (storing activations), making larger batches and deeper models feasible on the same hardware.

- Bigger batches can mean fewer total training steps and less time communicating across devices, which can speed up training overall.

- Stable, “energy-preserving” updates help keep information intact across many layers, which can improve learning and generalization.

What are the broader implications?

- More accessible AI: Teams with limited hardware can train and fine-tune powerful models more efficiently, reducing costs and energy use.

- Scalable training: Memory-efficient reversibility enables deeper models and larger batch sizes, which can shorten training time under fixed budgets.

- Practical adoption: Because you can convert existing pre-trained models with minimal fine-tuning, this approach can be adopted quickly without starting from scratch.

- Better long-range reasoning: The physics-inspired “energy-conserving” view helps models carry information across many layers without it getting lost, potentially improving performance on tasks that require long context.

In short, the paper shows a clear path to making LLM training more efficient: design layers you can reverse, save a lot of memory, process more data faster, and keep accuracy solid—all while being able to retrofit models we already use today.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed as concrete items future work can address.

- Lack of guarantees for stability in realistic nonlinear settings: analysis is primarily for linearized “test equations” and constant coefficients; no rigorous stability guarantees are provided for full transformer blocks with layer norm, attention, and MLPs under mixed nonlinearity and data-dependent Jacobians.

- Unclear mechanisms to enforce stability conditions in practice: the constant-coefficient analysis requires Jacobian eigenvalues to be purely imaginary (or negative real) and constraints like |a|=1 and |b + λh| ≤ 2, but the paper does not propose parameterizations, normalization, or regularization strategies (e.g., skew-symmetric/antisymmetric parametrizations, spectral normalization) to make transformer blocks satisfy these constraints during training.

- Step-size h and coefficient aℓ,bℓ selection is underspecified: h is treated as a hyperparameter and aℓ,bℓ are sometimes set to 1 and elsewhere randomized; there is no guidance on how to choose or adapt h and aℓ,bℓ across depth, tasks, or scales, nor ablations quantifying sensitivity and failure modes.

- Energy-conservation claim is unvalidated in practice: the paper asserts “energy-preserving” or “conservative dynamics” but does not define an explicit energy functional for transformer blocks nor measure energy drift across layers to empirically verify conservation or relate it to generalization.

- Reversibility under stochasticity and nondeterminism not addressed: dropout, data augmentation noise, stochastic depth, and GPU nondeterminism (atomic ops, fused kernels) can break reversible reconstruction unless RNG states/masks are recorded; no strategy is provided to ensure consistent recomputation.

- Mixed-precision and numerical error accumulation are not analyzed: reversibility relies on re-evaluating f(p) in reduced precision (bfloat16/FP16) where rounding errors can accumulate across hundreds of layers; there is no numerical robustness study (e.g., error growth vs. depth, precision choices, loss scaling) or mitigation (e.g., Kahan summation, selective FP32).

- Interaction with modern memory/throughput baselines is missing: there is no head-to-head comparison against activation checkpointing, selective activation recomputation, FlashAttention/Flash-Decoding, ZeRO/FSDP, tensor/pipeline/sequence parallelism, or offloading—making it unclear how much net benefit reversibility brings in state-of-practice training stacks.

- End-to-end wall-clock training under realistic pipelines is underreported: throughput improvements are reported on isolated setups; there is no tokens-per-second accounting including data loading, distributed communication, optimizer steps, gradient accumulation, and mixed-precision kernels.

- Optimizer and parameter-state memory not considered: claims focus on activation memory; however, large LLM training is often dominated by optimizer states (e.g., Adam’s 2–3× parameter memory) and gradients; the net memory footprint reduction at scale is not quantified.

- Attention-specific memory costs and long-context regimes are untested: while activation memory is depth-independent, attention still scales quadratically with sequence length in training; no experiments or analysis are provided for long-context training (e.g., 8k–128k tokens), nor exploration of pairing reversibility with efficient attention variants.

- Inference-time implications are unclear: reversibility mainly aids training; the paper does not measure inference latency/throughput, KV-cache behavior, or any trade-offs introduced by the reversible updates during generation.

- Retrofitting method lacks robustness analysis: the conversion relies on approximating p_{j−1} and KL alignment to the original model with limited data; there are no studies on how much data/compute is needed to preserve performance, how robust alignment is across domains, or how higher-order fixed-point iterations (k > 1) trade off compute vs. fidelity.

- Missing evaluation of the “higher-order estimator” in practice: the proposed fixed-point refinement to estimate p_{j−1} is not empirically evaluated (no k-sweep), leaving open whether it materially improves alignment or stability and at what cost.

- No large-scale or instruction-tuned evaluations: results are shown for GPT-2 (124M/772M), TinyLlama, and SmolLM2; there is no evidence on multi-billion to tens-of-billions parameter models, instruction tuning, RLHF/DPO, tool-use, or multi-turn dialogue performance.

- Limited statistical rigor and variance reporting: improvements are small on several benchmarks; there is no report of run-to-run variance, confidence intervals, or statistical significance, leaving uncertainty about robustness of the gains.

- Interaction with adapters/LoRA and parameter-efficient fine-tuning is unexplored: it is not shown whether reversible dynamics are compatible with LoRA/adapters, how to apply reversibility when only subsets of weights are trainable, or whether memory savings persist in PEFT regimes.

- Compatibility with fused kernels and fast attention implementations: the feasibility of using FlashAttention-2/3, xFormers, Triton kernels, or vendor fused ops within reversible recomputation is not examined, nor potential performance regressions due to kernel availability.

- Pipeline and model-parallel training interactions are open: it is unclear how reversible recomputation affects pipeline bubbles, inter-stage activation interfaces, and communication patterns in tensor/pipeline parallel training.

- Lack of guidelines for selecting which reversible scheme to use: midpoint vs. leapfrog vs. Hamiltonian updates are proposed, but there is no decision framework or empirical mapping from task/model characteristics to the most stable/effective scheme.

- No analysis on gradient quality and optimization dynamics: constraining dynamics to reversible/energy-preserving forms could alter curvature, conditioning, and optimization; there is no study on gradient norms, Hessian spectra, or training stability across depths.

- Potential generalization–batch-size trade-offs untested: the throughput gains come from much larger physical batch sizes; there is no comparison to gradient accumulation (same effective batch) to isolate whether performance differences are architectural or batch-size driven.

- Sequence length, head count, and model-width sensitivity absent: the memory and throughput gains are reported for specific hidden sizes and depths; no systematic scaling laws or sensitivity analyses are provided for d_model, n_heads, feedforward expansion, or sequence length.

- Limitations of the linear approximation bound for conversion: the provided error bound relies on small-norm operator assumptions; there is no non-linear bound nor empirical verification of when the approximation “falls apart” in modern LLM layers with large residual updates.

- Regularization and training tricks compatibility not discussed: weight decay, gradient clipping, stochastic depth, data augmentation, and EMA of weights may interact with reversibility; guidance for enabling these safely is missing.

- Safety of reversibility under catastrophic activations: if f(p) yields extreme values (e.g., due to rare out-of-distribution inputs), backward reconstruction might be numerically unstable; no safeguards or clipping strategies are proposed for reversible backprop.

- Licensing and ecosystem integration: there is no discussion of integrating the reversible updates into popular frameworks (DeepSpeed, Megatron-LM, vLLM) or implications for model zoos and checkpoints, including how to store/convert reversible states for downstream users.

Glossary

- Activation Recomputation: A technique that recomputes activations during the backward pass to save memory, instead of storing them. Example: "This idea is similar to ``Activation Recomputation''"

- Advection: A time-reversible physical transport process used as inspiration for model dynamics. Example: "time-reversible physical systems such as wave propagation, advection, and Hamiltonian flows"

- Arithmetic intensity: The ratio of computation to memory access in an operation, affecting backward pass cost. Example: "MLPs and attention modules with high arithmetic intensity tend to have costly backward steps"

- Automatic differentiation: A method to compute gradients programmatically, often costlier than forward evaluation. Example: "e.g., via automatic differentiation, is often significantly more expensive than the forward pass"

- Autoregressive generation: Generating tokens sequentially by predicting the next token from previous ones. Example: "This step yields a probability distribution over next tokens for autoregressive generation or language modeling objectives."

- Backpropagation: The process of computing gradients through the network, typically requiring stored activations. Example: "use time-reversible dynamics to retrieve hidden states during backpropagation, relieving the need to store activations."

- Conservative discretizations: Numerical schemes that preserve quantities (like energy) across layers or time steps. Example: "leveraging conservative discretizations that preserve information flow and guarantee reversibility."

- Conservative flows: Dynamics that conserve energy or information over depth, preventing dissipation. Example: "By modeling token dynamics as conservative flows, our architectures preserve the fidelity of representations across depth"

- Diffusion-based networks: Architectures modeled on diffusion processes that dissipate energy with depth. Example: "parabolic systems such as diffusion-based networks, which dissipate energy as depth increases"

- Eigenstructure: The set of eigenvalues/eigenvectors of a transformation, impacting stability of dynamics. Example: "especially when has eigenstructure with nonzero real parts."

- Energy dissipation: Loss of representational energy as depth increases, common in parabolic systems. Example: "parabolic systems such as diffusion-based networks, which dissipate energy as depth increases"

- Energy conservation: Preservation of a discrete analogue of energy across layers in reversible dynamics. Example: "ability to conserve energy over time"

- Explicit midpoint integrator: A reversible numerical method for first-order ODEs used to update hidden states. Example: "inspired by an explicit midpoint integrator commonly used for time-reversible numerical integration of first-order differential equations."

- Finite-difference discretization: Approximating derivatives using differences to simulate differential equations in layers. Example: "which corresponds to a finite-difference discretization of the second-order system"

- Foundation model: A large pre-trained model serving as a base for downstream fine-tuning. Example: "pre-trained LLM considered a foundation model."

- Forward Euler equation: A first-order explicit integration method referenced for stability comparison. Example: "behaves in expectation just like the forward Euler equation in terms of stability."

- Forward-backward stability: Stability of both forward and reverse passes under reversible dynamics. Example: "implying that there is no forward-backward stable method for a complex ."

- Hamiltonian dynamics: Reversible, energy-preserving dynamics using coupled position and momentum variables. Example: "We now introduce a third reversible architecture motivated by Hamiltonian dynamics"

- Hamiltonian flows: Time-reversible physical flows governed by Hamiltonian mechanics used for model inspiration. Example: "time-reversible physical systems such as wave propagation, advection, and Hamiltonian flows"

- Hyperbolic differential equations: Equations (e.g., waves) modeling conservative, time-reversible dynamics across layers. Example: "reversible architectures for LLMs based on hyperbolic differential equations"

- Inductive bias: Built-in structural preference of a model that guides learning and information propagation. Example: "This inductive bias supports stable long-range information propagation"

- Invertible update rules: Layer transformations that can be exactly reversed to reconstruct intermediate states. Example: "using invertible update rules (e.g., \eqref{eq:midpoint}, \eqref{eq:leapfrog}, \eqref{eq:hamil}), so only inputs and final outputs must be stored."

- Jacobian: The matrix of partial derivatives of a transformation, whose eigenvalues affect stability. Example: "real positive eigenvalues in the Jacobian of "

- Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence: A measure of difference between two probability distributions used for alignment. Example: "KL\left(Y_{\rm rev}, Y_{\rm fe}\right)"

- Leapfrog integrator: A second-order, reversible integration scheme improving stability for oscillatory dynamics. Example: "Like the leapfrog integrator, this update is fully reversible"

- Marginally stable: A property where systems neither grow nor decay, posing training challenges. Example: "reversible networks are typically only marginally stable"

- Nonlinear wave equation: A second-order hyperbolic PDE used to motivate the leapfrog architecture. Example: "specifically, the nonlinear wave equation."

- Oscillatory dynamics: Behavior with periodic variations that reversible second-order updates handle well. Example: "improved handling of oscillatory dynamics"

- Parabolic systems: Diffusive systems that dissipate energy, contrasted with conservative hyperbolic dynamics. Example: "parabolic systems such as diffusion-based networks"

- Residual update scheme: A structure that adds learned transformations to hidden states for stable training. Example: "This structure forms a residual update scheme"

- Reversible architectures: Network designs that allow exact reconstruction of activations without storing them. Example: "we introduce memory-efficient, reversible architectures for LLMs"

- Reversible LLMs: LLMs whose layer updates can be inverted to save memory. Example: "In this section, we introduce our reversible LLMs."

- Second-order dynamics: Dynamics involving second time derivatives, enabling energy-conserving behavior. Example: "Both the Hamiltonian and leapfrog updates represent {\em second-order dynamics}"

- Staggered update scheme: Alternating updates of coupled states (e.g., position and momentum) in Hamiltonian models. Example: "through a staggered update scheme resembling the symplectic Euler integrator"

- Step size: The discretization interval controlling the magnitude of layer updates in integrators. Example: " is a fixed step size"

- Symplectic differential equations: Structure-preserving equations from Hamiltonian systems inspiring reversible designs. Example: "inspired by symmetric and symplectic differential equations"

- Symplectic Euler integrator: A structure-preserving integrator used to update coupled Hamiltonian states. Example: "resembling the symplectic Euler integrator for Hamiltonian systems"

- Test equation: A simplified linear model used to analyze stability of numerical schemes. Example: "we study the test equation "

- Throughput: The rate of data processed during training, often improved by larger batch sizes. Example: "thereby offering improved throughput."

- Time-reversible dynamics: Dynamics that can be run backward to reconstruct previous states exactly. Example: "use time-reversible dynamics to retrieve hidden states during backpropagation"

- Token dynamics: The evolution of token representations across layers modeled as physical-like flows. Example: "By modeling token dynamics as conservative flows"

- Volume-preserving propagation: Dynamics that conserve flow volume, maintaining representational fidelity. Example: "volume-preserving propagation of information across depth"

- Wave propagation: A physical, time-reversible phenomenon used to motivate hyperbolic model updates. Example: "time-reversible physical systems such as wave propagation, advection, and Hamiltonian flows"

- Zero-shot evaluation: Assessing model performance on tasks without task-specific fine-tuning. Example: "we conduct zero-shot evaluation on five downstream benchmarks"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The paper introduces reversible, energy-conserving LLM architectures and a practical retrofitting (conversion) method that enable constant activation memory during training and fine-tuning. This can be acted on immediately in multiple settings:

- Memory-efficient fine-tuning on limited hardware

- Sector: software, healthcare, finance, legal, public sector

- Use case: Adapt foundation models (e.g., GPT-2, LLaMA-style, TinyLlama, SmolLM2) to domain-specific corpora on a single 24–48 GB GPU by converting to reversible blocks and fine-tuning

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Retrofit pipeline using the paper’s reversible Midpoint update and KL-alignment (distillation) objective; combine with LoRA/QLoRA/adapters

- PyTorch modules for reversible transformer blocks integrated into Hugging Face Transformers training loops

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Access to model weights and a modest calibration dataset (e.g., WikiText scale) for alignment

- Careful handling of stochastic ops (dropout RNG seeding), mixed precision (BF16 preferred), and step-size/stability hyperparameters

- Training throughput and cost optimization in cloud/HPC environments

- Sector: AI labs, cloud providers, enterprise MLOps

- Use case: Increase effective batch size by ~10× and improve throughput by 20–100% (reported up to 101% at 96 layers) under memory-bound regimes, reducing wall-clock time and GPU-hour cost

- Tools/products/workflows:

- “Reversible mode” in training orchestrators to auto-scale batch size when memory frees up

- Cost dashboards that report FLOPs vs. throughput trade-offs for reversible vs. baseline runs

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Benefits materialize primarily when memory, not compute, is the bottleneck; recomputation adds ~30–50% per-layer forward overhead during backprop

- On-prem and privacy-preserving fine-tuning

- Sector: regulated industries (healthcare, finance, defense), government

- Use case: Keep sensitive data in-house by enabling fine-tuning on fewer, smaller GPUs

- Tools/products/workflows:

- “ReversibleFT” internal toolkit that converts selected pre-trained checkpoints to reversible form, then runs PEFT methods locally

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Governance requirements still apply (data handling, audit); reversible training does not change inference-time privacy properties

- Faster experimentation for academic labs and SMEs

- Sector: academia, startups

- Use case: Run deeper or more ablations per day on the same hardware by fitting larger batches/deeper models without activation checkpoints

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Reversible blocks as a drop-in replacement for residual blocks in common research codebases (e.g., nanoGPT-style recipes)

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Stability-sensitive hyperparameters (step size h, a_j schedule) must be tuned; follow paper’s recipes to avoid divergence

- Long-context training under fixed memory budgets

- Sector: legal-tech, code intelligence, scientific literature processing

- Use case: Train with longer sequences or deeper stacks at the same GPU RAM, improving long-range representation propagation (energy-conserving dynamics)

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Curriculum that jointly scales depth and sequence length; memory planning combining reversible blocks with flash attention and gradient checkpointing for attention

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Reversibility removes depth-related activation memory, not the O(L·T2) attention cost; attention memory/time still scale with sequence length T

- Energy/carbon efficiency tracking and sustainability initiatives

- Sector: enterprise sustainability, cloud FinOps

- Use case: Reduce energy per processed sample by leveraging larger batches; report lower carbon per epoch for memory-bound jobs

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Training telemetry that logs energy/sample and contrasts reversible vs. baseline runs

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Gains rely on operating in the memory-bound regime; in compute-bound regimes, recomputation overhead may offset benefits

- Improved cluster utilization and scheduling

- Sector: HPC schedulers, MLOps platforms

- Use case: Pack more concurrent training jobs per node by lowering per-job activation footprints; dynamic batch tuning per device

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Scheduler plugins that detect reversible jobs and admit more concurrent workers or larger per-worker batches

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Interacts with distributed strategies; communication overheads (data/model parallel) remain

- Education and curriculum in physics-inspired deep learning

- Sector: academia, professional training

- Use case: Teach PDE/symplectic ideas through hands-on reversible LLM labs that fit on commodity GPUs

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Classroom notebooks illustrating Midpoint/Leapfrog/Hamiltonian blocks, stability regions, and empirical memory/time trade-offs

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Students need math prerequisites for stability analysis; provide simplified defaults

- Open-source extensions and model zoos

- Sector: OSS ecosystems

- Use case: Provide reversible variants of popular backbones (GPT-2, LLaMA-family) and reference training scripts

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Transformers PRs adding ReversibleMidpoint/Leapfrog layers; conversion utilities shipping as CLI tools

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Must validate equivalence via alignment loss; maintainers will require robust tests and benchmarks

- Safer, more stable deep stacks

- Sector: software, safety research

- Use case: Leverage energy-conserving dynamics (hyperbolic/second-order) to reduce representational dissipation and oversquashing in very deep models

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Depth-scaling studies with automated stability monitors and step-size schedulers

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Proper choice of a, b, h parameters; guardrails for eigenvalue regimes per paper’s stability analysis

- Personal and hobbyist fine-tuning

- Sector: daily life, indie developers

- Use case: Fine-tune chat/code assistants on a single 24 GB consumer GPU without activation checkpointing

- Tools/products/workflows:

- “One-GPU reversible fine-tune” guides combining reversible conversion + LoRA for local datasets

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Users manage CUDA/driver/toolchain versions; mixed precision stability considerations apply

Long-Term Applications

Beyond immediate deployment, the paper’s methods open pathways that require further R&D, scaling, or co-design:

- Foundation reversible LLM families at large scale

- Sector: AI labs, model providers

- Use case: Pre-train 7B–70B reversible models offering lower training RAM, improved depth scalability, and comparable or better downstream performance

- Tools/products/workflows:

- “RevLLM” checkpoints; training recipes standardized around reversible blocks

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Engineering for distributed training (tensor/pipeline parallel) and stability at scale; rigorous evals on diverse benchmarks

- Hardware–algorithm co-design for reversible training

- Sector: semiconductor, accelerators

- Use case: Architect memory hierarchies and kernels that exploit activation-free backprop and deterministic recomputation

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Reversible-aware compilers and kernels; RNG determinism hardware support; kernel fusion for multi-use recomputations

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Vendor adoption; integration with CUDA/ROCm/XLA and graph compilers

- On-device and edge fine-tuning

- Sector: mobile, IoT, automotive, robotics

- Use case: Personalize medium-size models on laptops/edge devices using reversible training to stay within RAM/power envelopes

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Lightweight reversible training runtimes; adapter-based PEFT stacks with reversible cores

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Further efficiency gains (e.g., low-rank adapters + 4/8-bit training) and thermal constraints

- Federated and cross-silo learning with lower client memory

- Sector: healthcare networks, finance consortia, telecom

- Use case: Enable clients with constrained GPUs to participate in training by cutting activation memory

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Federated orchestration that negotiates reversible configurations per client; privacy-preserving alignment

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Communication remains a bottleneck; privacy guarantees independent of reversibility

- Ultra-deep or effectively infinite-depth sequence models

- Sector: research, foundational AI

- Use case: Explore limits of depth scaling with energy-conserving dynamics for stable long-range reasoning and memory

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Depth growth schedules, dynamic step-size controllers, spectral monitoring of Jacobians

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Theoretical and empirical validation that generalization scales with depth under these dynamics

- Robustness, continual learning, and stability research

- Sector: safety, reliability

- Use case: Study whether energy-preserving flows mitigate catastrophic forgetting and improve robustness to distribution shift

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Continual learning benchmarks using reversible cores; diagnostics of “energy” over layers as a health signal

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Requires dedicated longitudinal evaluations; current evidence is suggestive but not conclusive

- Interpretable dynamics via Hamiltonian formulations

- Sector: interpretability research

- Use case: Leverage position/momentum split to probe how attention (global flow) and MLP (local forces) contribute to reasoning

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Probing tools that visualize trajectory “energy” and phase-space dynamics across layers

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Needs standardized “energy” proxies and careful mapping to linguistic behavior

- Multimodal reversible transformers

- Sector: vision-language, speech, embodied AI

- Use case: Apply reversible blocks to VLMs and speech models to cut training memory and stabilize deep fusion backbones

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Reversible cross-attention and encoder–decoder stacks; symplectic updates for multi-stream fusion

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- New stability regimes for heterogeneous modalities; attention scaling still dominates long-context memory/time

- Regulatory and sustainability frameworks

- Sector: policy, ESG reporting

- Use case: Reference reversible training as a best practice for memory-bound efficiency and carbon accounting in AI procurements/grants

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Reporting templates capturing energy/sample and memory footprint reductions attributable to reversible methods

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Standard-setting bodies adopt compute/energy metrics; independent verification ecosystems mature

- AutoML and compilers that “make models reversible”

- Sector: software tooling

- Use case: Automated conversion of residual models into reversible approximations with stability checks and fine-tuning

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Graph-level pattern rewriters; auto-selection of a_j, step-size h, and fixed-point iterations for p_{j-1} estimation

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Broad model coverage (RMSNorm, RoPE, SwiGLU, gating) and robust numerical handling

- Communication-aware distributed reversible training

- Sector: large-scale training systems

- Use case: Reduce activation traffic across pipeline stages by reconstructing states locally during backward

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Pipeline parallel schedulers that leverage reversibility to minimize activation stashing/sends; overlap recomputation with comms

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Net benefits depend on network topology; needs careful choreography with model/tensor parallel strategies

- Personalization marketplaces and “bring-your-own-checkpoint” services

- Sector: platforms, SaaS

- Use case: Offer conversion + fine-tune pipelines that let customers adapt third-party checkpoints under tight RAM limits

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Managed reversible conversion, alignment, and PEFT services with compliance options (VPC, on-prem connectors)

- Assumptions/dependencies:

- Licensing constraints for model weights; SLA for performance parity after conversion

Notes on Feasibility and Key Dependencies

- Stability and hyperparameters: Reversible updates require careful choice of coefficients (a, b) and step size h; stability regions differ for midpoint, leapfrog, and Hamiltonian variants.

- Numerical precision: BF16/FP32 are safer for reversibility than aggressive FP16; ensure deterministic RNG for invertibility across forward/backward.

- Attention complexity: Reversibility removes depth-related activation storage but does not solve quadratic attention time/memory; combine with efficient attention methods.

- Scale-up engineering: While results cover GPT-2 and ~1–2B parameter models, scaling to multi-billion parameter pretraining needs distributed systems work and extensive validation.

- Retrofitting quality: Conversion preserves performance when f_j updates are “small” (typical of residual nets); quality may degrade if layers are highly non-linear or poorly conditioned; fixed-point refinement improves approximation at additional cost.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.