Language-conditioned world model improves policy generalization by reading environmental descriptions (2511.22904v1)

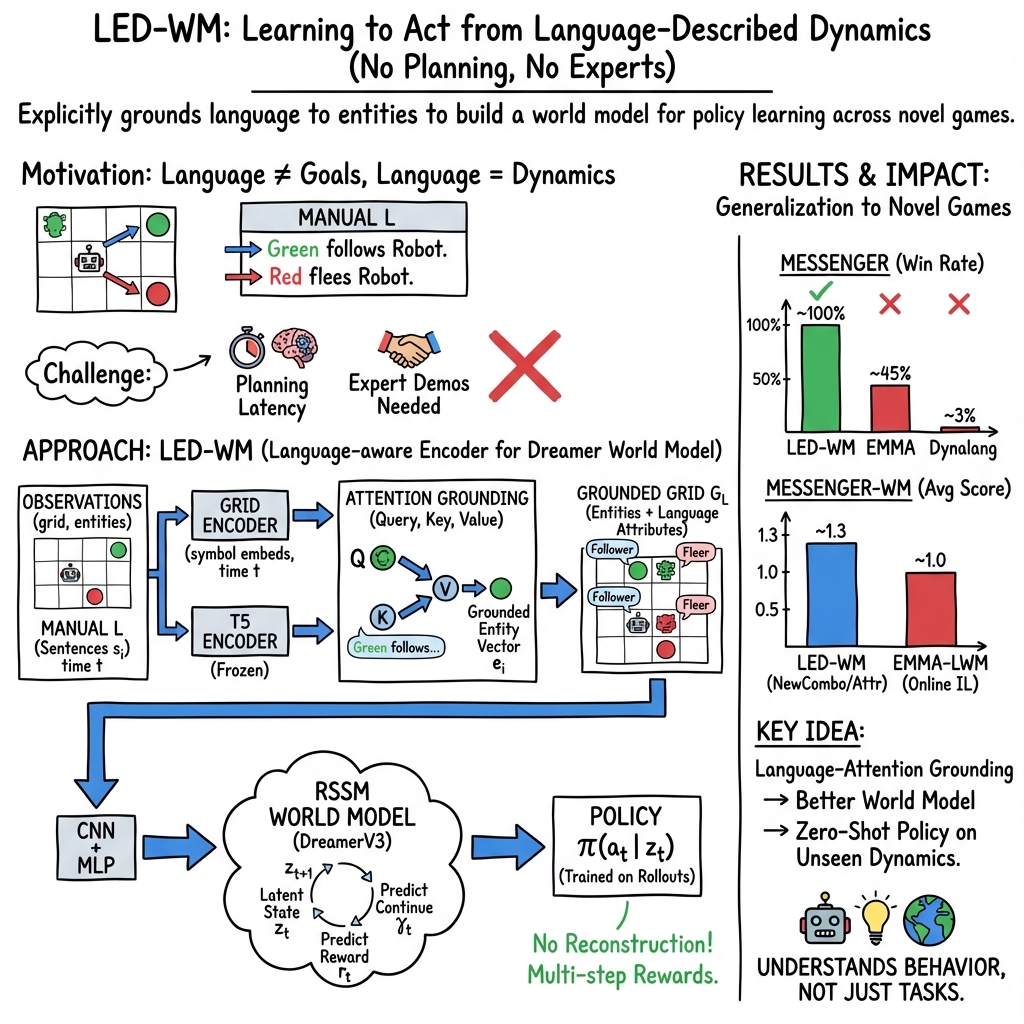

Abstract: To interact effectively with humans in the real world, it is important for agents to understand language that describes the dynamics of the environment--that is, how the environment behaves--rather than just task instructions specifying "what to do". Understanding this dynamics-descriptive language is important for human-agent interaction and agent behavior. Recent work address this problem using a model-based approach: language is incorporated into a world model, which is then used to learn a behavior policy. However, these existing methods either do not demonstrate policy generalization to unseen games or rely on limiting assumptions. For instance, assuming that the latency induced by inference-time planning is tolerable for the target task or expert demonstrations are available. Expanding on this line of research, we focus on improving policy generalization from a language-conditioned world model while dropping these assumptions. We propose a model-based reinforcement learning approach, where a language-conditioned world model is trained through interaction with the environment, and a policy is learned from this model--without planning or expert demonstrations. Our method proposes Language-aware Encoder for Dreamer World Model (LED-WM) built on top of DreamerV3. LED-WM features an observation encoder that uses an attention mechanism to explicitly ground language descriptions to entities in the observation. We show that policies trained with LED-WM generalize more effectively to unseen games described by novel dynamics and language compared to other baselines in several settings in two environments: MESSENGER and MESSENGER-WM.To highlight how the policy can leverage the trained world model before real-world deployment, we demonstrate the policy can be improved through fine-tuning on synthetic test trajectories generated by the world model.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

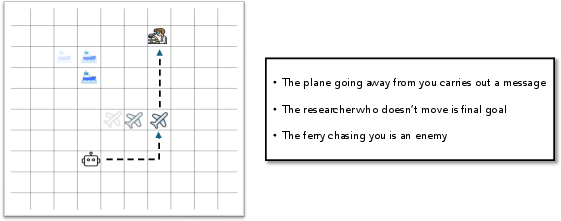

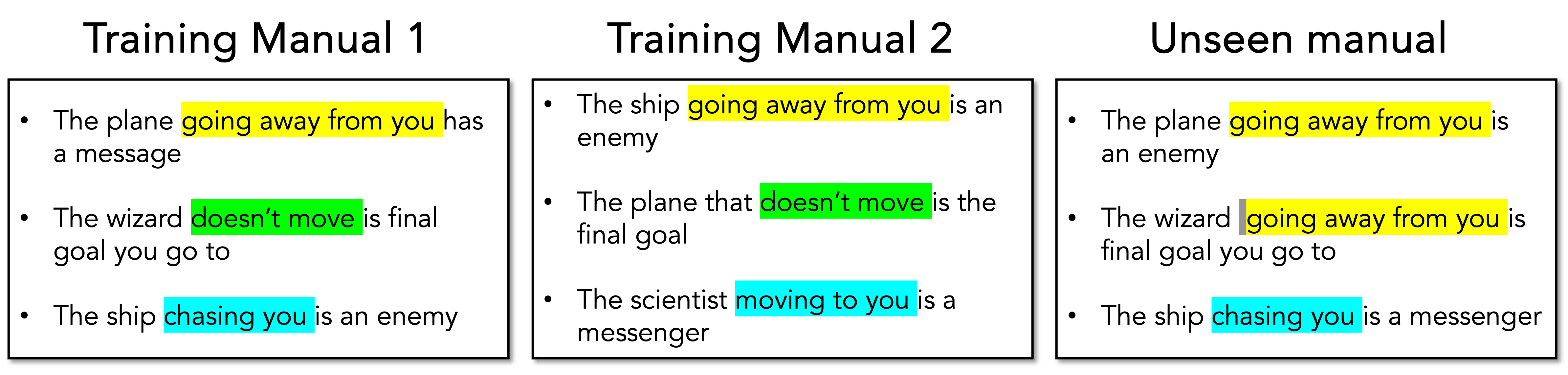

This paper is about teaching AI agents to understand language that describes how a world behaves, not just what task to do. Imagine a robot playing a simple grid-based game with different moving characters. The robot gets a short manual written in plain language—like “the plane stays still,” or “the ferry moves away from you”—and must use that to figure out who is the messenger, who is the goal, and who is the enemy. The paper shows a way to help the robot “read” these manuals and use them to act well—even in new games it has never seen before.

Key Objectives

The researchers wanted to find out:

- How to build an agent that understands dynamics-descriptive language (language about how things move and interact), not just task instructions.

- Whether a language-aware “world model” can help the agent generalize (do well) in new, unseen game setups and manuals.

- How to avoid common limitations in previous methods, like needing expert demonstrations or slow planning at decision time.

- Whether the agent can be improved further by practicing on fake (simulated) experiences generated by its own world model.

How Did They Do It?

The Game World

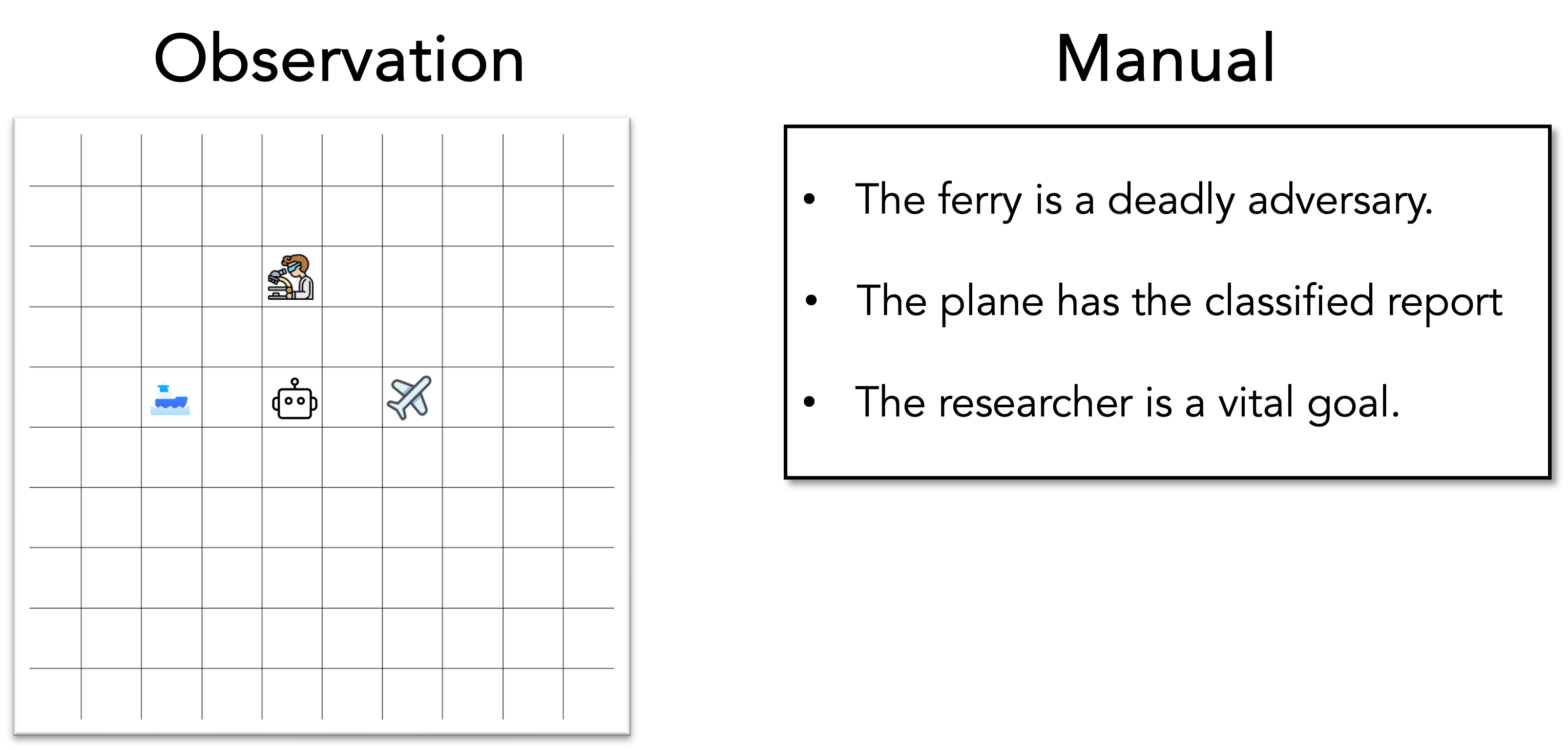

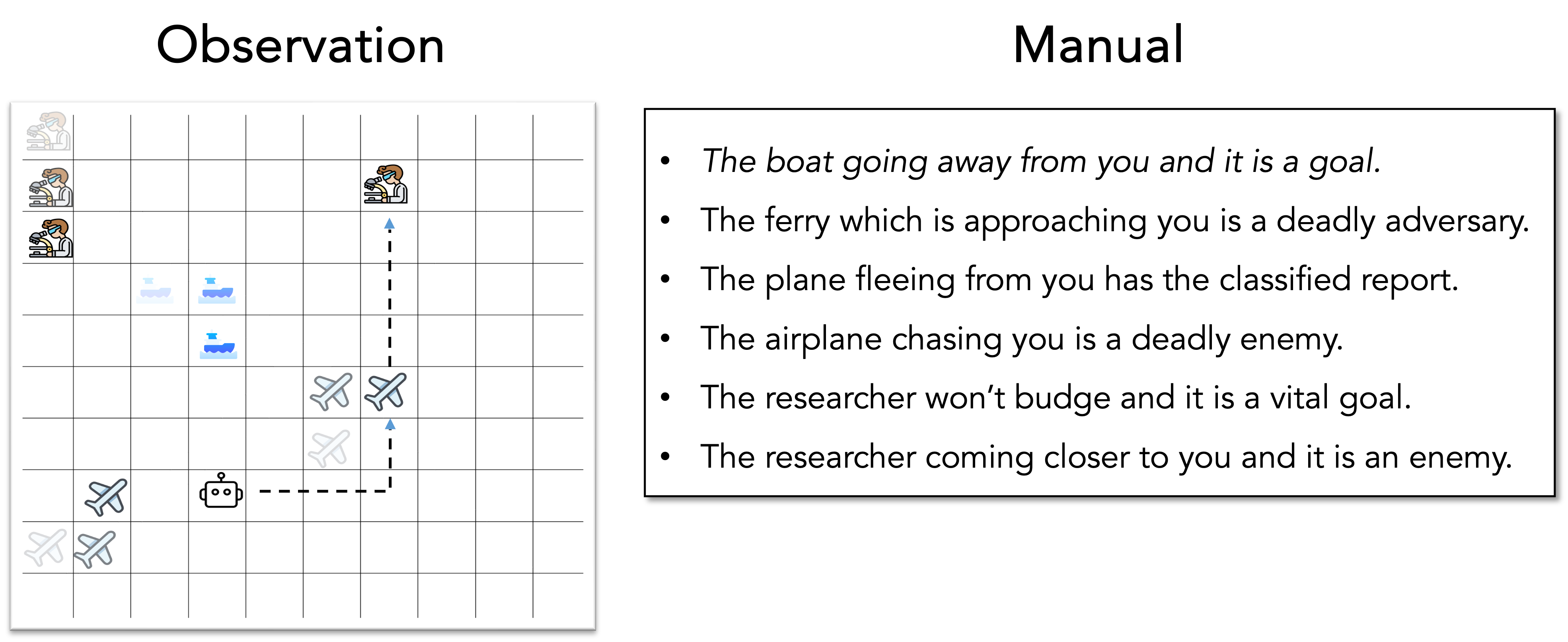

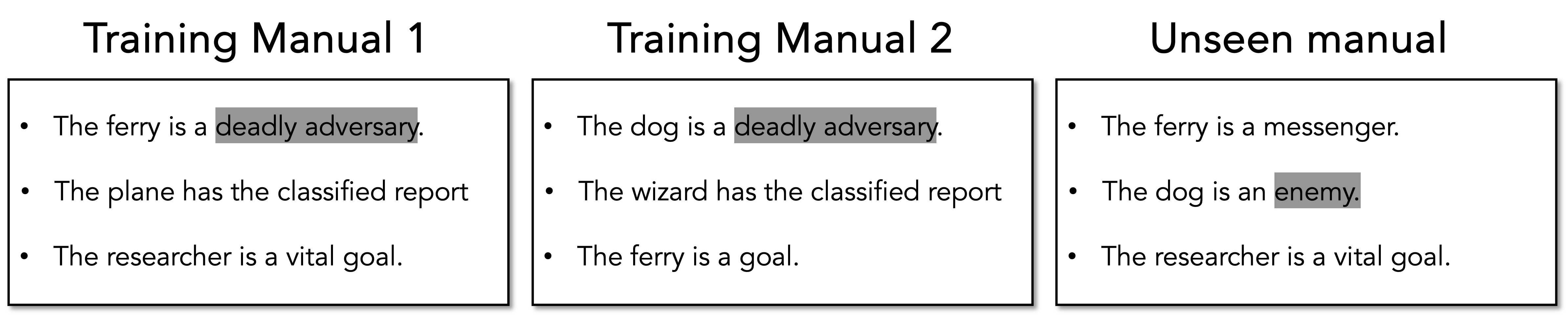

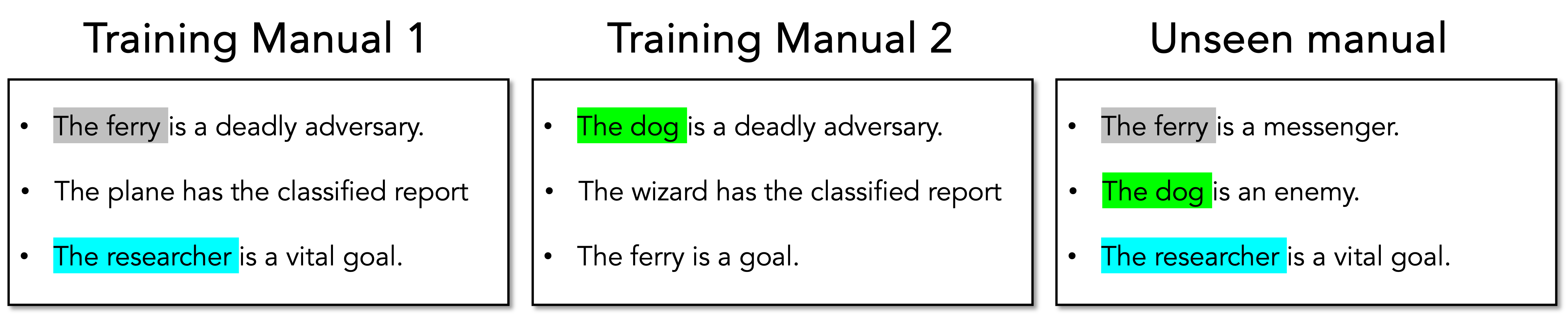

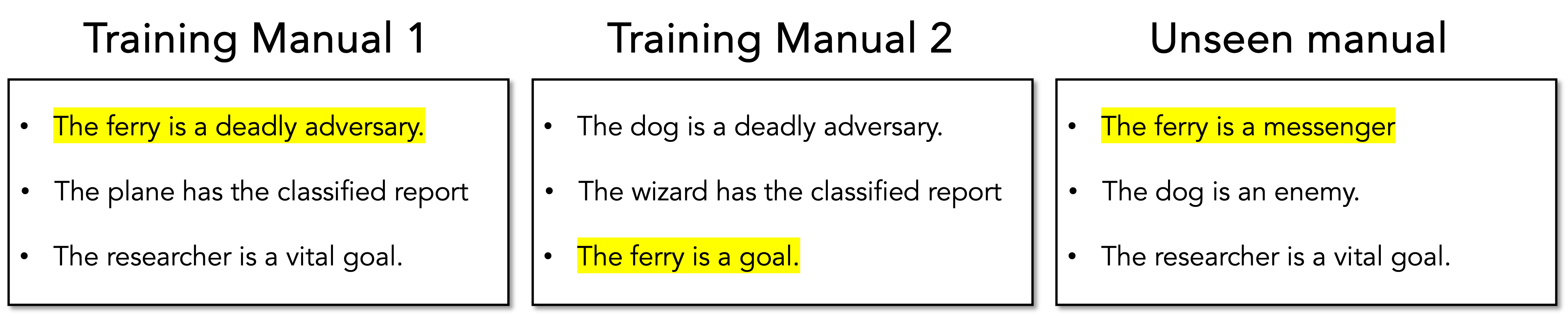

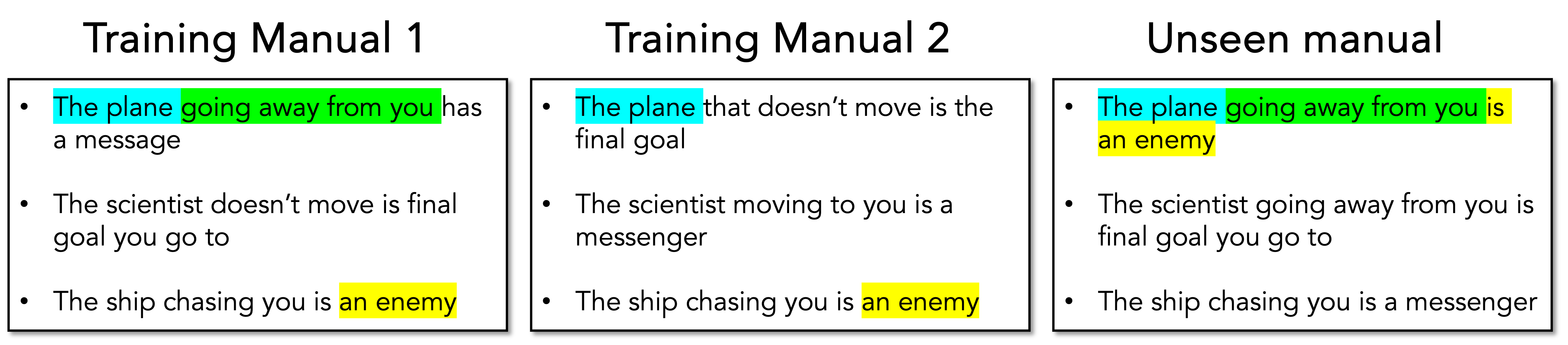

The agent plays grid-based games called MESSENGER and MESSENGER-WM:

- The world is a 10×10 grid with symbols for entities (like a ferry, plane, scientist) and the agent.

- Each entity has a role: messenger (who gives a message), goal (where to deliver the message), or enemy (to avoid).

- The agent can move left, right, up, down, or stay.

- A short language manual describes how each entity behaves (e.g., “the scientist stays put” or “the ferry runs away from you”) and what role they have.

The challenge: The agent must read the manual, watch how entities move, match descriptions to the right symbols, and then plan how to deliver the message safely.

Building a “World Model” That Reads Manuals

Think of a world model like the agent’s internal video game simulator. It learns the rules of the game and can predict what will happen next when the agent takes different actions.

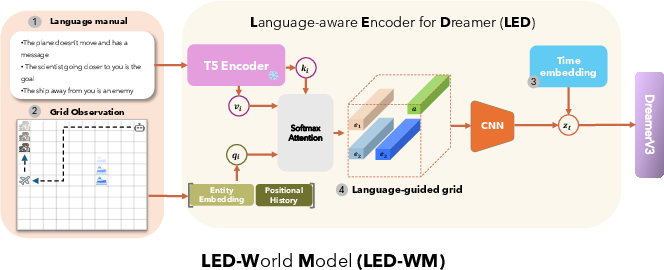

The authors build LED-WM (Language-aware Encoder for Dreamer World Model), based on a powerful method called DreamerV3:

- The agent encodes the grid (where things are) and the manual (what the text says about each entity).

- It uses attention (like a smart matching spotlight) to align each sentence in the manual with the correct entity symbol in the grid.

- This produces a “language-aware grid”—a map where each entity is enriched with the language describing how it moves and what role it plays.

- The world model then uses this enriched map to predict future states and rewards, helping train a good policy (the agent’s way of choosing actions).

Analogy: If you’re playing a board game and you have a rulebook, LED-WM helps the player “attach” the right rules to the right game pieces, so it knows how each piece will behave.

Training Without Shortcuts

Many existing methods either:

- Require expert demonstrations (someone showing the agent exactly what to do), or

- Use slow planning at decision time (like searching a big tree of possibilities before each move).

LED-WM avoids both:

- It learns by interacting with the environment (trial and error).

- It trains a policy directly from the world model, without planning during inference.

- Later, it can fine-tune the policy using synthetic practice games created by the world model itself.

What Did They Find?

The authors tested LED-WM against several baselines in MESSENGER and MESSENGER-WM (which include different levels of “newness,” like unseen language, new combinations of entities, and new movement dynamics).

Here’s what stood out:

- LED-WM strongly outperformed the model-based EMMA-LWM in all MESSENGER-WM settings, even though EMMA-LWM needed expert demonstrations and LED-WM did not.

- LED-WM beat or matched other methods in several MESSENGER stages, especially when the test games used familiar movement patterns but with new descriptions or combinations.

- A previous method (Dynalang) failed to generalize to new games—likely because it didn’t explicitly match language to each entity the way LED-WM does.

- In one tough setting (MESSENGER S2), LED-WM underperformed a specialized baseline (CRL) that includes a technique to handle training data bias. However, LED-WM did very well in a similar setting (S2-dev) where the test dynamics matched training dynamics.

- Fine-tuning the policy using synthetic practice from the world model improved results in some test settings, showing that the world model’s rollouts are useful for adapting to new games.

Why It’s Important

- Understanding dynamics-descriptive language helps agents adapt to new situations using familiar concepts. For example, if the manual says “the scientist won’t move,” the agent can match that to any stationary symbol—even if it’s called “researcher” or “scientist.”

- Generalization is crucial. Real-world tasks change often, and agents need to handle new combinations of known behaviors and new language phrasing.

- Avoiding expert demos and slow planning makes agents more practical and faster in real use.

Takeaway and Potential Impact

This work shows that teaching an agent to “read” the world’s rules and match them to what it sees can make it more flexible and reliable. LED-WM bridges language understanding with world modeling, letting the agent:

- Ground language to specific entities,

- Predict how the environment changes,

- Learn a strong policy without expert help or slow planning,

- Adapt further with simulated practice.

In the long run, this approach could help build robots and digital assistants that respond naturally to human descriptions (“the floor is slippery,” “this machine overheats if used too long”) and act safely and efficiently in new situations.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of concrete gaps and open questions that remain unresolved and could guide future research:

- External validity beyond toy domains: The approach is only evaluated in discrete, symbolic grid worlds (MESSENGER, MESSENGER-WM). It is unknown whether LED-WM scales to visually rich, continuous-control environments (e.g., robotics, Atari, embodied agents) with perception noise, occlusions, and partial observability.

- One-to-one sentence–entity assumption: Manuals are constructed with exactly one sentence per entity and equal cardinality between sentences and entities. Handling mismatches (extra/missing sentences), multi-sentence descriptions per entity, sentences describing multiple entities, global rules, coreference, or ambiguous/contradictory language is not explored.

- Language complexity and phenomena: The method’s robustness to complex linguistic phenomena (negation, quantifiers, comparatives, temporal references, anaphora/coreference, conditional rules, multi-step dependencies), noisy text (typos), multi-lingual manuals, or mixed-structure documentation (tables + text) is not evaluated.

- Frozen language encoder: The T5 encoder is frozen and low-dimensional. The trade-offs of fine-tuning, using larger LLMs, adapters, or task-specific pretraining for dynamics-descriptive language remain untested.

- Grounding fidelity measurement: There is no direct metric or evaluation of how accurately attention aligns sentences to entities (e.g., assignment accuracy, precision/recall of role/movement grounding). Developing and validating explicit grounding metrics is needed.

- Limited dynamics coverage: Movement types and dynamics are narrow (e.g., chaser, fleeing, stationary). Generalization to richer, interacting dynamics (inter-entity interactions independent of the agent, stochastic transitions, continuous velocities, collision/contact effects) is unknown.

- S2 failure mode and data bias: LED-WM underperforms CRL in S2 due to training on a single movement combination, suggesting spurious correlations. How to mitigate distributional bias in MBRL (e.g., constraints, invariance penalties, data augmentation, adversarial reweighting, causal regularization) is an open design question.

- Component-wise attribution and ablation: The paper changes DreamerV3 (removing reconstruction decoder, multi-step predictors) and adds LED. There is no ablation quantifying each component’s contribution (LED vs temporal array D_i vs CNN choice vs decoder removal) or sensitivity to hyperparameters.

- World model quality metrics: World model generalization is inferred indirectly via policy fine-tuning improvements. Direct evaluation (multi-step prediction error, likelihood of state transitions, calibration, roll-out divergence, counterfactual consistency under language changes) is missing.

- Synthetic rollouts for fine-tuning: Fine-tuning on model-generated trajectories yields modest gains and risks model bias. When and how synthetic data helps (trajectory selection, uncertainty-aware filtering, model-based regularization, Dyna-style schedules) and its failure modes are not rigorously characterized.

- Thresholding and triggering fine-tune: The heuristic to trigger fine-tuning based on an estimated policy value threshold is not justified or analyzed (sensitivity, calibration of value estimates, false positives/negatives, adaptive or Bayesian criteria).

- Generalization breakdown by novelty type: While tables summarize novelty categories, results do not disentangle performance by specific novelty sources (language-only vs role-reassignment vs movement-combination shifts). A controlled, per-factor analysis would clarify where LED-WM helps or fails.

- Scalability to variable entity counts and layouts: Beyond 3 and 5 entities, how the encoder handles variable numbers, dense scenes, overlapping entities, or dynamic appearance/disappearance is unknown.

- Interaction beyond agent-centric signals: Query construction uses the entity’s motion relative to the agent. Handling dynamics that depend on inter-entity relations (e.g., enemy chases messenger) or global rules not referenced to the agent is unaddressed.

- Robustness to misaligned or noisy manuals: The approach assumes accurate manuals aligned with true environment dynamics. Performance under noisy, outdated, partial, or adversarial language and mechanisms for consistency checking/correction are unknown.

- Inference-time efficiency and deployment: The paper argues against MCTS latency but does not quantify LED-WM’s inference costs (T5 encoding, attention, CNN, RSSM) or its suitability for real-time control under resource constraints.

- Combining planning with learned policies: It remains open whether limited-depth planning or lookahead (e.g., model-predictive control, tree search hybrids) could further improve generalization without incurring prohibitive latency.

- Transfer to other language-dynamics benchmarks: Generalization to datasets like RTFM, TextWorld, ALFWorld, or visually grounded language tasks (e.g., RLBench + manuals) is not studied.

- Role and reward grounding: Manuals encode both transition and reward functions, but there is no analysis of separating/grounding these components, or of credit assignment when language specifies sparse/delayed rewards.

- Perception-to-symbol pipeline: The method assumes perfect symbolic observations. How to integrate object discovery/segmentation, slot-based representations, or detection uncertainty with language grounding is an open integration challenge.

- Safety and stability under fine-tuning: Potential catastrophic forgetting when fine-tuning on synthetic test trajectories and strategies to maintain prior capabilities (e.g., rehearsal, regularization, conservative updates) are not examined.

- Fairness of baseline comparisons: Baselines use reported results or different training budgets; compute-normalized, sample-efficiency comparisons (including learning curves) are missing, limiting causal claims.

- Hyperparameter sensitivity and reproducibility: Many hyperparameters (e.g., latent unimix, free nats, embedding dims) lack justification. Systematic sensitivity analysis, code/model release, and reproducibility audits are needed.

- Limits of attention-only grounding: The encoder uses cross-modal attention over sentence and entity embeddings. Exploring structured representations (graphs, slots, relational reasoning), neuro-symbolic constraints, or causal models might yield more robust grounding and generalization.

Glossary

- Attention mechanism: A neural mechanism that learns to focus on relevant parts of inputs by computing similarity between queries and keys. "features an observation encoder that uses an attention mechanism to explicitly ground language descriptions to entities in the observation."

- Behavior policy: The policy that determines how an agent acts, often distinguished from target or optimal policies in RL. "language is incorporated into a world model, which is then used to learn a behavior policy."

- Compositional generalization: The ability to generalize to new combinations of known components or attributes not seen during training. "enables evaluation at compositional generalization for world model and policy."

- Convolutional neural network (CNN): A neural network architecture using convolutional layers, commonly for spatial feature extraction. "which is then processed by a CNN."

- Cross-modal attention: An attention mechanism that aligns information across different modalities (e.g., language and vision). "uses cross-modal attention to align game entities with sentences."

- Curriculum learning: Training strategy that introduces tasks in increasing difficulty to stabilize or accelerate learning. "The policy is trained via curriculum learning where the agent is initialized with parameters learned from previous easier game settings."

- DreamerV3: A model-based RL framework that learns a latent world model and optimizes policies in imagination. "built on top of DreamerV3"

- Dynamics-descriptive language: Language that describes how an environment evolves over time, including entity interactions. "Understanding this dynamics-descriptive language is important for human-agent interaction and agent behavior."

- Fine-tuning: Post-training adjustment of a model or policy on additional data to improve performance on specific tasks. "we demonstrate the policy can be improved through fine-tuning on synthetic test trajectories generated by the world model."

- Grid-world: A discrete 2D environment represented as a grid where entities and agents occupy cells. "MESSENGER \cite{emma} is a 10 × 10 grid-world environment."

- Hierarchical bootstrap sampling: A resampling method that accounts for multiple levels of variability (e.g., episodes and trials). "hierarchical bootstrap sampling \cite{Davison2013-hr} corresponding to two levels of hierarchies in our experiments (episodes and run trials)"

- Imitation learning (Online imitation learning): Learning a policy by mimicking expert actions, often with supervision during simulated interaction. "through online imitation learning and filtered behavior cloning."

- Language-conditioned world model: A world model that incorporates language to predict environment dynamics and rewards. "a language-conditioned world model is trained through interaction with the environment"

- Language grounding: Mapping language descriptions to specific entities or features in the environment. "we aim to develop a world model capable of doing language grounding to entities in a game."

- Latent representation: A compact, learned embedding of observations used by the model for prediction and planning. "These inputs are compressed into a latent representation z_t"

- Markov Decision Process (MDP): A formal framework for sequential decision-making defined by states, actions, transitions, and rewards. "We define our problem as a language-conditioned Markov Decision Process"

- Model-based reinforcement learning (MBRL): RL that learns a model of environment dynamics to plan or learn policies using imagined rollouts. "We adopt a model-based reinforcement learning (MBRL) approach"

- Model-free methods: RL approaches that learn policies directly from interaction without an explicit model of dynamics. "Model-free methods \cite{emma, crl} directly map language to a policy."

- Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS): A planning algorithm that builds a search tree using Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate actions. "Reader uses a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to look ahead and generate a full plan."

- Multi-layer perceptron (MLP): A feedforward neural network composed of multiple fully connected layers. "we employ a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) that processes the entity embedding and its temporal information"

- Out-of-distribution dynamics: Environment dynamics at test time that differ from those seen during training. "multiple stages to evaluate policy generalization over out-of-distribution dynamics"

- Policy generalization: The ability of a learned policy to perform well on tasks or environments not seen during training. "either do not demonstrate policy generalization to unseen language or rely on limiting assumptions."

- Recurrent State-Space Model (RSSM): A recurrent latent dynamics model used to predict future latent states and rewards. "uses Recurrent State-Space Model (RSSM) \cite{Hafner2018-db} to build a recurrent world model."

- Reward function: A mapping from state-action pairs to scalar feedback that the agent seeks to maximize. "transition function and reward function ."

- Scaled dot-product attention: An attention computation that scales dot-product similarities by the dimension to stabilize training. "We then apply scaled dot-product attention \cite{Vaswani2023-iq}."

- Soft actor-critic: An off-policy RL algorithm that maximizes expected reward and entropy for robust exploration. "Dynalang \cite{dynalang} use soft actor-critic for policy learning."

- Synthetic trajectories: Model-generated rollouts used to train or fine-tune policies without interacting with the real environment. "generate 60 synthetic trajectories."

- T5 encoder: The encoder component of the T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) model used for language embeddings. "are encoded using a T5 encoder \cite{Raffel2023-ru}"

- Transition function: The probabilistic mapping from current state and action to the next state in an MDP. "transition function and reward function ."

- Wilcoxon signed-rank test: A non-parametric statistical test for paired data to assess median differences. "Wilcoxon signed-rank \cite{Wilcoxon1945-sa}"

- World model: A learned model of environment dynamics and rewards used to simulate future trajectories. "We base our world model on DreamerV3 \cite{dreamerv3}"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below is a concise set of deployable use cases that leverage the paper’s LED-WM method (a language-aware encoder built on DreamerV3) and its demonstrated ability to generalize policies from dynamics-descriptive language without expert demonstrations or inference-time planning.

- Sector: Robotics, Industrial Automation

- Application: Text-driven site onboarding for mobile/warehouse robots

- Description: Robots adjust their navigation and interaction behaviors by reading local operational “manuals” (e.g., “aisle 3 is slippery; avoid pushing heavy carts there”) to generalize behavior to new combinations of known entities.

- Tools/Workflows: Manual-to-policy pipeline using LED-WM; attention-based language grounding module to align entity mentions to observed entities; offline synthetic rollout fine-tuning prior to entering a new site.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable entity detection and mapping from text to perceived entities; concise dynamics-descriptive manuals; discrete interaction spaces or an abstraction layer that converts continuous perception into discrete entities; LED-WM’s current strengths (generalization to novel language and combos) and limits (sensitivity to data bias on unseen dynamics like S2).

- Sector: Software Engineering, DevOps for Agent Systems

- Application: Rule-change regression testing for agentic systems

- Description: “What-if manual” testing to evaluate and fine-tune agent behavior under new textual rules (e.g., swapping entity roles or movement patterns) before deployment.

- Tools/Workflows: LED-WM synthetic trajectory generator; automated thresholds for triggering fine-tune (as in paper’s policy value check); CI integration for agent QA.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to representative text descriptions of environment dynamics; fixed latency constraints favoring model-based learning without online planning.

- Sector: Gaming, Simulation

- Application: NPCs that adapt to dynamic rule books and mods

- Description: Game AI reads changing rule descriptions (“the wizard now chases the player but avoids traps”) and generalizes behavior to new rule combinations without developer-provided demos.

- Tools/Workflows: LED-WM embedded in game engine; mod-to-world-model parser; synthetic rollout fine-tuning for balance and behavior predictability.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Entities and roles are represented discretely; rule text is amenable to T5-like embeddings and attention alignment; clear grounding of rule descriptions to in-game entities.

- Sector: Smart Home, Consumer Robotics

- Application: Home cleaning and courier robots responding to environment state changes

- Description: Users issue dynamics-descriptive commands (“the living room is wet; avoid pushing chairs; the cat sleeps near the window”) and the robot adapts interactions accordingly.

- Tools/Workflows: LED-WM module with lightweight entity abstraction (rooms, furniture, pets); pre-deployment synthetic trajectories to validate safety; low-latency control policy without planning.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robust entity recognition and mapping to language; simple movement patterns and discrete interaction primitives; user-provided language is clear and grounded.

- Sector: Academia, AI Education

- Application: Teaching language-grounded model-based RL

- Description: Course labs and research projects using MESSENGER/MESSENGER-WM-like tasks to paper generalization from dynamics-descriptive language, attention-based grounding, and synthetic rollout fine-tuning.

- Tools/Workflows: LED-WM open-source module; benchmark kits; ablation studies on encoder choices, bias mitigation, and compositional generalization.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of structured environments; faculty access to compute and baseline implementations.

- Sector: Safety and Risk Management (Policy Pilots)

- Application: Machine-readable operational notes for agent safety checks

- Description: Facilities provide concise textual hazard descriptions that agents ingest to adjust behaviors (e.g., “reactive spill present; avoid rapid motion near coordinate range”).

- Tools/Workflows: Draft templates for dynamics-descriptive manuals; LED-WM-based preflight synthetic rollout to ensure the agent’s value exceeds a safety threshold; pre-deployment fine-tune when below threshold.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Organizational willingness to author dynamics-descriptive text; minimal ambiguity in language; mapping from text hazards to actionable agent policies.

- Sector: RPA (Robotic Process Automation), Enterprise Software

- Application: Text-conditioned workflow agents

- Description: Agents adapt to textual changes in process dynamics (e.g., “approvals will time out after 30 minutes; retries must increase backoff”) and generalize across unseen combinations of known steps.

- Tools/Workflows: LED-WM conceptual analog using discrete workflow entities and rules; synthetic “rollout” of process states to fine-tune; invariant grounding to avoid spurious role-entity correlations.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Workflow states can be abstracted into discrete entities and dynamics; consistent mapping from text to state transitions.

- Sector: Digital Twins (Operations)

- Application: Authoring environment dynamics via text to validate agent behavior

- Description: Operators describe dynamic changes (e.g., role reassignment of devices, altered movement policies) and simulate how agents would respond before deployment.

- Tools/Workflows: Text-to-world-model authoring interface; LED-WM-based simulation of trajectories; policy adjustment pipeline driven by synthetic rollouts.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of a discrete twin model; sufficient fidelity for policy transfer; clarity of textual dynamics and consistent grounding.

Long-Term Applications

Below are forward-looking uses that will benefit from further research, scaling to continuous perception, bias mitigation, and standardization of dynamics-descriptive language.

- Sector: Industrial Robotics and Manufacturing

- Application: Robots reading SOPs and hazard notices to self-adjust in complex, continuous environments

- Description: Agents ingest plant-specific manuals and signage (“conveyor friction fluctuates; keep low contact force near line B”) to adapt without external demos or online planning.

- Tools/Workflows: Multimodal LED-WM (vision + language) extended to continuous spaces; robust grounding from unstructured text to visual entities; domain bias mitigation (akin to CRL constraints).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable perception-to-entity grounding; standardized plant-level “machine-readable” dynamics descriptions; validation frameworks for safety-critical deployment.

- Sector: Healthcare Operations

- Application: Hospital service robots aligning with dynamic protocols

- Description: Agents interpret protocol text (“avoid isolation rooms; handoff at nurse station only during rounds”) to generalize navigation and interaction without handcrafted plans.

- Tools/Workflows: Medical protocol-to-world-model parser; compliance-aware policy learning; continuous-space extensions of LED-WM.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Clear clinical language mapping to operational dynamics; stringent safety and regulatory approvals; robust entity detection in crowded, variable environments.

- Sector: Autonomous Vehicles and Drones

- Application: Adapting to temporary signage, notices, and airspace bulletins

- Description: Vehicles read textual advisories (“lane closure shifts inbound traffic; slow-moving convoy ahead”) and modify driving/flying policies accordingly.

- Tools/Workflows: Language-grounded world modeling integrated with HD maps and perception; real-time policy adjustment without heavy planning; simulation-based fine-tuning.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: High-fidelity grounding from text to dynamic scene elements; latency and compute constraints; fail-safe overrides and certification.

- Sector: Disaster Response and Public Safety

- Application: Agents ingest incident reports to model hazards and adapt behavior

- Description: Robots interpret on-the-fly textual hazard updates (“floor collapse risk; avoid vibration; keep distance from structural supports”) to generalize behaviors rapidly.

- Tools/Workflows: Text-to-dynamics mapping integrated with hazard models; constrained policy updates from synthetic rollouts; safety thresholds before operational deployment.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate, timely reports; robust language disambiguation in stressful contexts; strong safety envelopes and human-in-the-loop oversight.

- Sector: Energy, Utilities, and Infrastructure Maintenance

- Application: Field robots adjusting to dynamic site conditions described in manuals

- Description: Agents interpret text on slippery surfaces, temperature extremes, or reactive materials to adapt movement and manipulation strategies.

- Tools/Workflows: Multimodal LED-WM with thermals and tactile sensing; entity-role grounding for equipment and zones; synthetic trajectory validation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable sensing and entity abstraction; standardized site documentation; scaling beyond discrete testbeds.

- Sector: Digital Twins and Industrial Simulation

- Application: Language interfaces for authoring and validating complex environment dynamics

- Description: Textual authoring (“valves alternate high-pressure cycles every 10 min; avoid simultaneous actuator triggers”) drives world model configuration, enabling rapid scenario testing and agent policy calibration.

- Tools/Workflows: Authoring language schema for dynamics; compositional generalization; integration with continuous simulators.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Standardization across vendors; domain-adapted embeddings and grounding; robust transfer from simulated to real.

- Sector: Enterprise Compliance and Policy Automation

- Application: Compliance-aware agents simulating consequences of policy changes described in text

- Description: Agents read compliance updates (“escalations require dual approval; retries must not exceed two per hour”) and simulate workflow dynamics to adjust policies.

- Tools/Workflows: LED-WM analog for business processes; synthetic rollouts for stress-testing compliance impacts; invariance constraints to mitigate spurious correlations.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Precise mapping from textual rules to process dynamics; auditability and explainability requirements.

- Sector: Foundation Models + World Models (Research)

- Application: LLM-integrated, language-grounded world models for rich, continuous environments

- Description: Joint architectures combining LLMs (for nuanced language grounding) with RSSM-like dynamics for scalable generalization; multi-step prediction and safety-aware finetuning.

- Tools/Workflows: LLM-augmented encoder replacing frozen T5; perception-language alignment pipelines; benchmark suites extending MESSENGER/MESSENGER-WM to realistic domains.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Compute and data scale; stability under domain shift; methods for mitigating data bias (e.g., constraints akin to CRL) and handling ambiguous language.

Cross-cutting Notes on Feasibility and Dependencies

- Grounding quality: Real deployments require robust perception-to-entity mapping; current paper assumes discrete grids with symbolic entities. A perception abstraction layer is needed for continuous, high-dimensional settings.

- Language quality and standardization: Dynamics-descriptive text must be clear, unambiguous, and consistently tied to environment states and rewards. Industry templates and standards will accelerate adoption.

- Bias mitigation: The paper shows LED-WM can underperform in data-biased settings (S2). Incorporating constraints to avoid spurious correlations (similar to CRL) will improve generalization to unseen dynamics.

- Compute and latency: LED-WM’s avoidance of inference-time planning is favorable for low-latency applications; training and synthetic rollout generation will still require compute budgets.

- Safety and certification: Pre-deployment fine-tuning with synthetic trajectories is promising, but safety-critical sectors need additional guardrails, explainability, and validation protocols.

- Tooling: Immediate product opportunities include a “manual-to-policy” SDK, a synthetic rollout fine-tuner, and benchmarking kits; long-term requires multimodal extensions and standard schemas for text-described dynamics.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.