Scale-Agnostic Kolmogorov-Arnold Geometry in Neural Networks (2511.21626v1)

Abstract: Recent work by Freedman and Mulligan demonstrated that shallow multilayer perceptrons spontaneously develop Kolmogorov-Arnold geometric (KAG) structure during training on synthetic three-dimensional tasks. However, it remained unclear whether this phenomenon persists in realistic high-dimensional settings and what spatial properties this geometry exhibits. We extend KAG analysis to MNIST digit classification (784 dimensions) using 2-layer MLPs with systematic spatial analysis at multiple scales. We find that KAG emerges during training and appears consistently across spatial scales, from local 7-pixel neighborhoods to the full 28x28 image. This scale-agnostic property holds across different training procedures: both standard training and training with spatial augmentation produce the same qualitative pattern. These findings reveal that neural networks spontaneously develop organized, scale-invariant geometric structure during learning on realistic high-dimensional data.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper studies a hidden pattern that seems to appear inside neural networks as they learn. The pattern is called Kolmogorov–Arnold geometry (KAG). In simple terms, it’s a special way information gets organized inside a network so that complex decisions can be built from many simpler steps. Earlier work saw this happen in tiny, toy problems. This paper asks: does the same organized pattern show up in real, high‑dimensional tasks like recognizing handwritten digits (MNIST)? The short answer: yes—and it shows up at many sizes and places across the image.

What questions did the authors ask?

In everyday language, the paper tries to answer:

- Do simple neural networks naturally form KAG while learning to recognize digits?

- Does this geometric pattern show up in small parts of the image, the whole image, and everything in between (that is, across “scales”)?

- Is the pattern stable even if we change how we train the network (for example, using data augmentation like shifting digits around)?

- Does the pattern look stronger in some layers or bigger networks?

How did they study it?

The dataset and models

- Task: Classify MNIST digits (28×28 grayscale images → 10 digit classes).

- Model: A 2-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP), a very standard kind of neural network. They tried different hidden sizes (64, 128, 256).

- Training setups:

- “Standard” training.

- “Augmented” training where images are randomly shifted (translations) during training to increase variety.

All models reached about 98% test accuracy (augmented ones were a bit lower but close), so performance wasn’t the main difference—internal geometry was.

What is “geometry” here?

Think of the network as a machine with many knobs. Each input pixel slightly turns some knobs inside the network. The Jacobian is like a big “sensitivity map” that tells you, for each input pixel, how much each hidden neuron reacts if you nudge that pixel. By studying this map, you can see whether the network organizes information in a special, structured way during learning.

- If many neurons don’t react locally (flat response), or if reactions line up in very particular ways, that’s a sign of KAG.

- The authors examine small “blocks” inside this sensitivity map to see how groups of pixels and neurons work together.

How they measured the hidden pattern

They tracked three simple statistics on many small pieces of the Jacobian (explained in everyday terms):

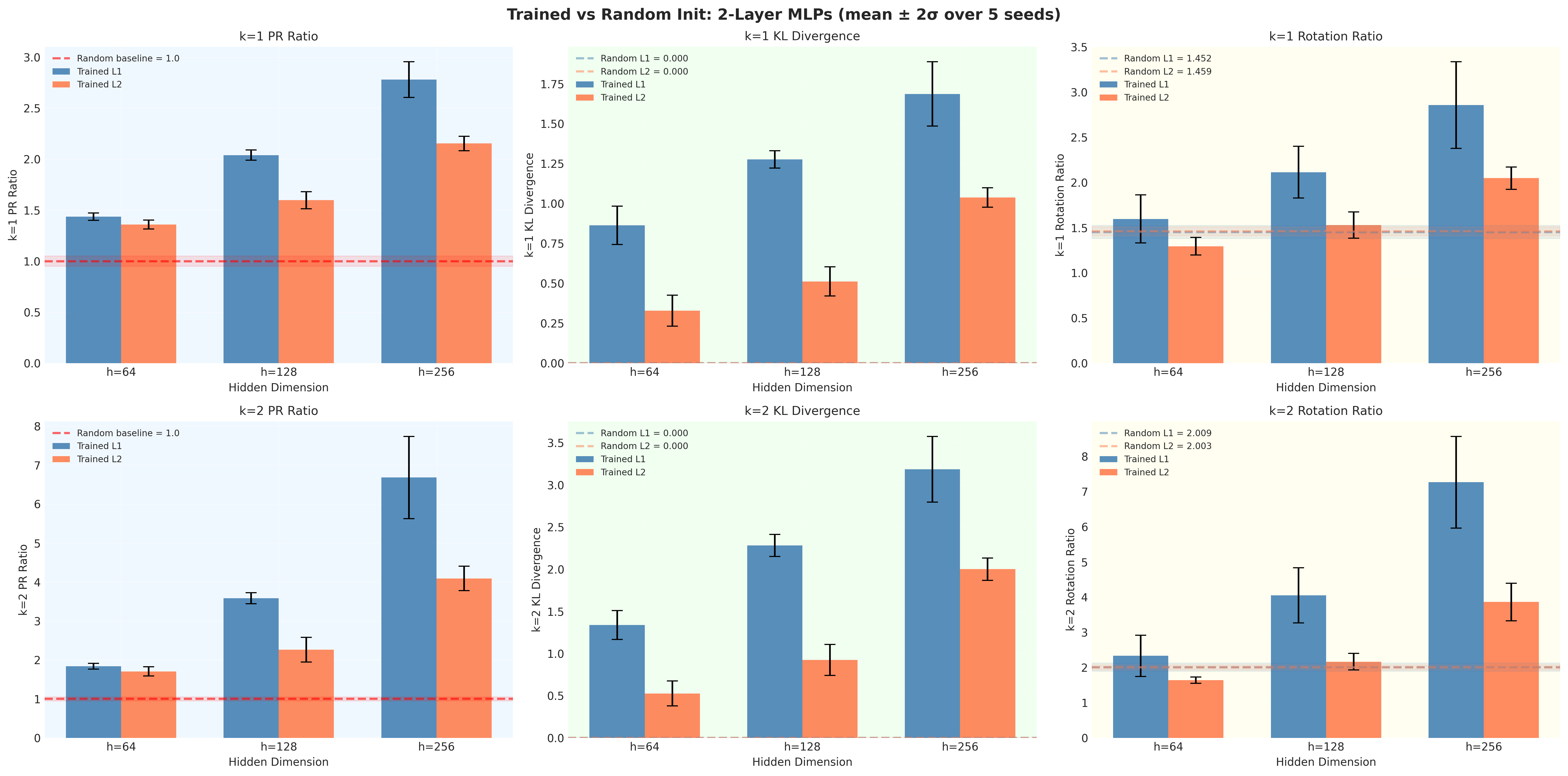

- Participation Ratio (PR): Are a few reactions much bigger than the rest? If yes, the distribution is “heavy-tailed,” a KAG signal. They report a PR Ratio comparing trained vs. untrained (random) networks. Bigger than 1 means training made the pattern stronger.

- KL Divergence: How much did the distribution of reactions change from the very start of training? Bigger change suggests the network learned a new structure (another KAG signal).

- Rotation Ratio (RR): They “shuffle” the neuron directions by rotating them randomly. If the structure is special (aligned with the network’s own axes), shuffling will weaken it. RR > 1 means the original alignment is real and not just random.

You can think of PR as “few big contributors vs. many small ones,” KL as “how different did things get after learning,” and RR as “is the pattern lined up in a meaningful way?”

Looking at different parts and scales of the image

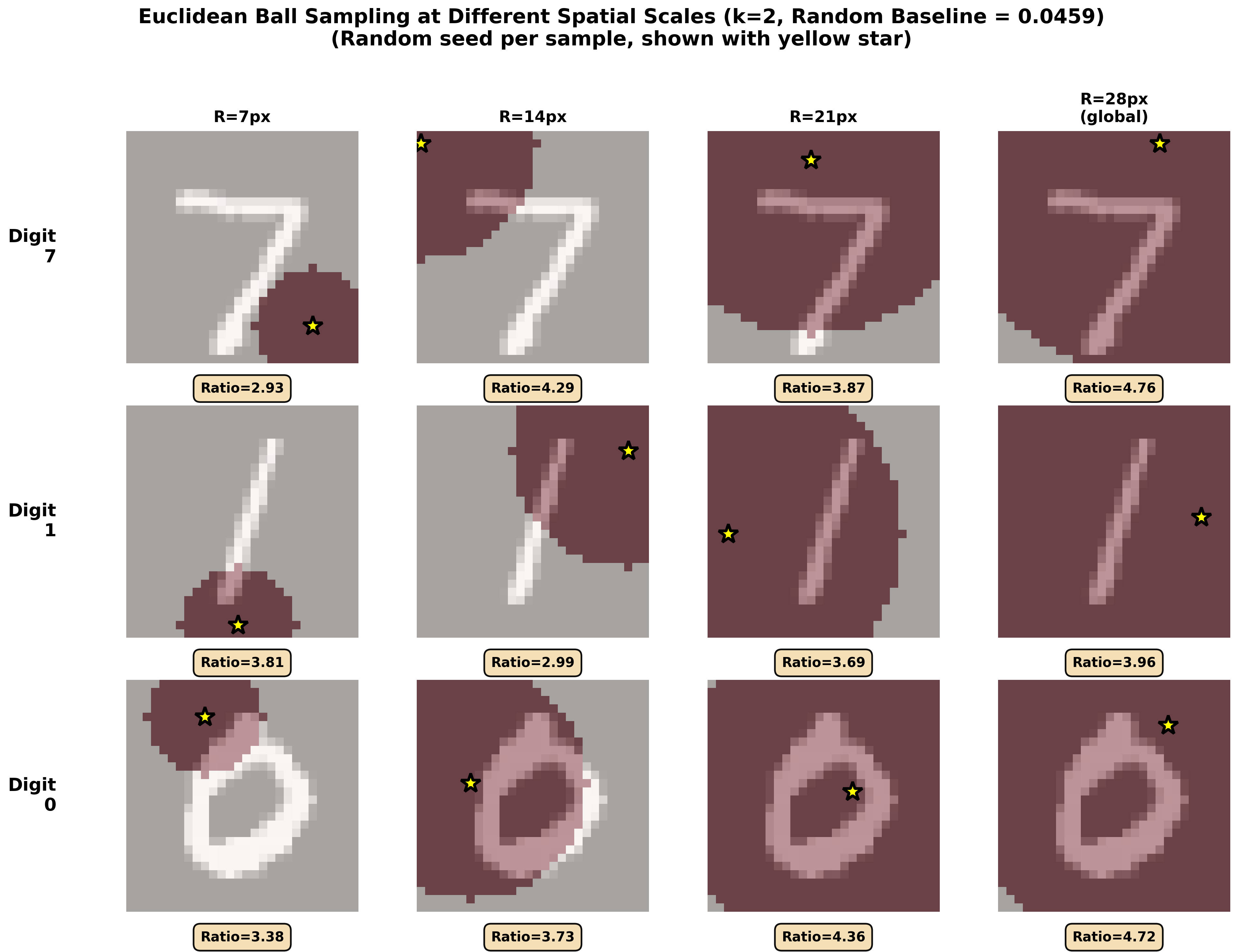

To test scale, they didn’t always use all 784 pixels. Instead, they:

- Looked at small neighborhoods (like circles of radius 7 pixels), medium ones, and up to the full image.

- Looked at different corners/regions of the image.

- Forced the selected pixels to be far apart (up to half the image’s width) to see if the pattern spans long distances.

If KAG shows up similarly across all these choices, it’s “scale-agnostic” (the same kind of structure appears from small patches to the entire picture).

What did they find and why is it important?

- KAG emerges reliably during training: Compared to random, untrained networks, trained networks showed much stronger KAG signals across PR, KL divergence, and RR.

- It’s scale-agnostic: The same KAG pattern appears whether you look at tiny local areas, large areas, or the whole image. It also holds when using pixels that are far apart, showing the geometry is global, not just local.

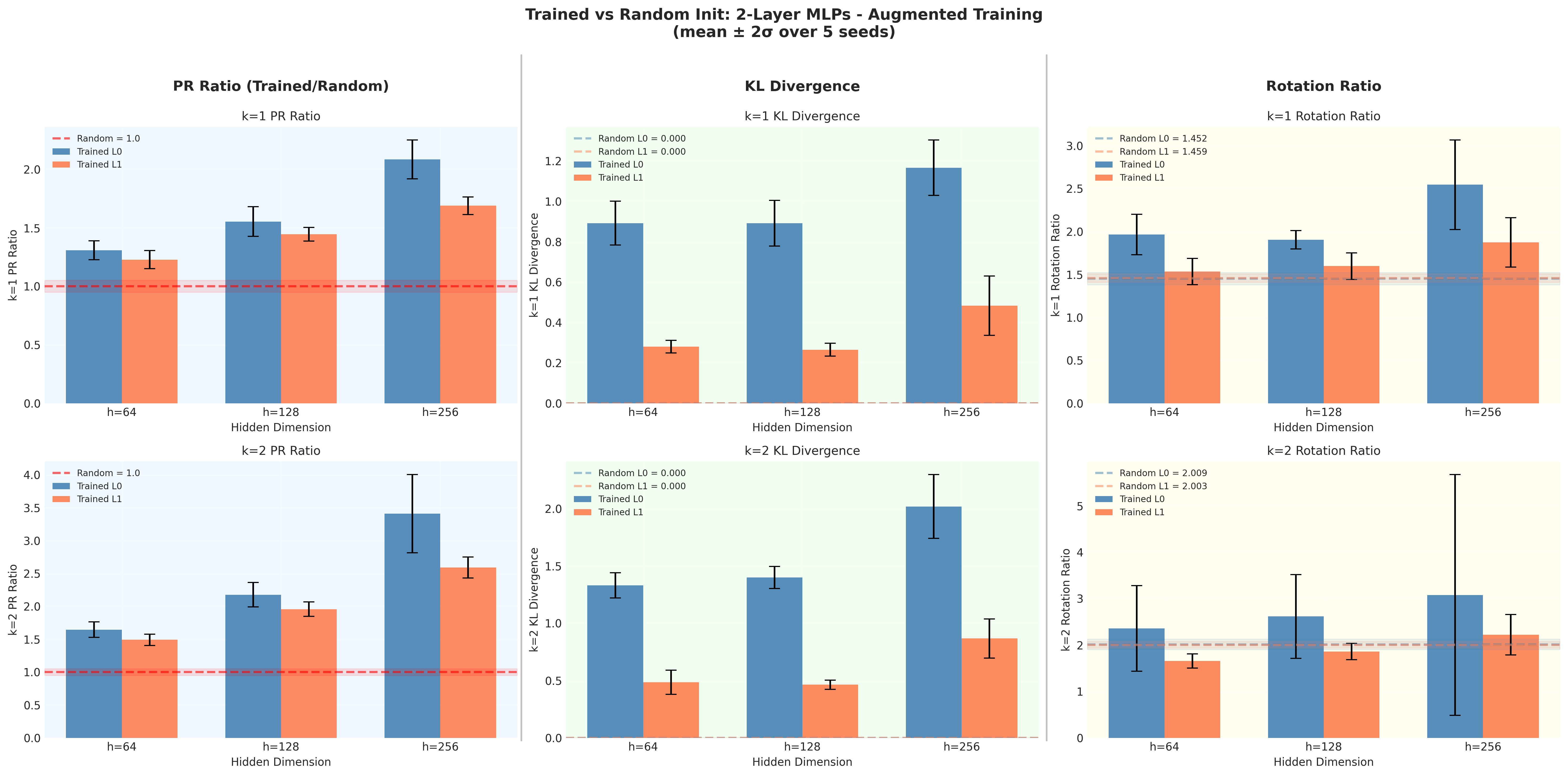

- It’s robust to training style: Whether trained normally or with spatial augmentation (shifting digits), the same overall pattern appears.

- Augmented training reduced the strength of the PR signal by about 30–40%, but the shape of the pattern stayed the same. This suggests that seeing more variety during training makes the network rely less on extremely concentrated geometry, even though it still uses similar structure.

- Stronger in the first layer: The first hidden layer shows clearer KAG signals than the second. That fits the idea that early layers “prepare” the data in a structured way, and later layers build on that.

- Bigger networks show stronger KAG: With more hidden units, the KAG signatures get more pronounced—even though accuracy is already high in smaller models. This means KAG isn’t just a byproduct of doing better on the task; it’s a way the network organizes itself internally.

Why it matters: These results suggest that neural networks naturally arrange their internal calculations into an organized, layered structure that works across different image sizes and regions. This may be a general principle of learning, not just a quirk of tiny toy problems.

What does this mean for the future?

- A possible general rule: The fact that KAG shows up in real data (MNIST), across scales, and across training methods hints that this geometry may be a basic feature of how neural networks learn—especially in early layers where data is “shaped” for later decisions.

- Training insights: If data variety reduces how extreme the geometry needs to be (yet preserves its pattern), we might use this to design better training procedures that balance generalization and structure.

- Open questions:

- Cause or effect? Does forming KAG help the network learn, or does learning naturally create KAG? Experiments that deliberately encourage or discourage these patterns could answer this.

- Does KAG appear in modern deep architectures (like CNNs, ResNets, Transformers) and on large-scale tasks? If yes, it could become a powerful lens for understanding and improving today’s AI systems.

In short, the paper shows that as networks learn, they build a tidy, scale-invariant internal structure—one that seems to be a natural outcome of training and may be key to how they solve complex tasks using simple building blocks.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, consolidated list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper. Each item is phrased to be directly actionable for future researchers.

- Generality beyond MNIST: Does scale-agnostic KAG persist on more complex vision datasets (e.g., CIFAR-10/100, ImageNet) and non-vision modalities (e.g., speech, language)?

- Architectural generality: Do CNNs, ResNets, Vision Transformers, and KANs exhibit the same KAG patterns under analogous analyses, or is KAG specific to fully connected MLPs?

- Depth and width scaling: How do KAG signatures change with deeper networks and with hidden widths in regimes h ≪ d and h ≫ d (including the KA-ideal regime h ≥ 2d + 1)?

- Activation dependence: Are KAG patterns robust to different nonlinearities (ReLU, LeakyReLU, tanh, ELU, SiLU) and to linear networks (to isolate the role of nonlinearity)?

- Optimization sensitivity: How do optimizer choice (SGD vs Adam/AdamW), learning-rate schedules, batch sizes, and weight decay affect KAG strength and emergence?

- Initialization effects: Does KAG depend on initialization schemes (e.g., Xavier, orthogonal, scaled Gaussian) or on bias initialization?

- Regularization impact: What is the effect of dropout, batch normalization, label smoothing, and stochastic depth on KAG metrics?

- Causality tests: Do interventions that induce or suppress KAG (e.g., explicit regularizers targeting PR/KL/RR, “frustration” pretraining on random labels) causally affect learning speed, generalization, or robustness?

- Training dynamics: The paper reports end-of-training results; how do KAG metrics evolve throughout training and correlate with phases like representation learning and convergence?

- Layer-wise propagation: How does KAG propagate across all layers, including the final logits layer and deeper architectures, and how does it interact with phenomena like neural collapse?

- Performance correlation: Is there a quantitative link between KAG strength and accuracy, calibration, margin, or sample efficiency (holding other factors fixed)?

- Robustness and shift: Do KAG signatures predict adversarial robustness, resistance to common corruptions, or transfer performance under distribution shifts?

- Class-conditional structure: Are KAG patterns consistent across digit classes or do certain classes induce stronger/weaker geometric signatures?

- Image-level variability: How much do KAG metrics vary across individual inputs; is there a systematic relationship with input complexity or uncertainty?

- Spatial analysis assumptions: The “spatial” analyses assume the canonical 2D raster ordering of pixels; how sensitive are KAG conclusions to random pixel permutations that destroy spatial adjacency?

- Input vs hidden alignment: RR rotates only the hidden dimension; does rotating the input basis (R ∈ SO(d)) or jointly rotating both spaces change alignment conclusions?

- Regional anisotropy: Rectangular patch analysis is described but detailed results are not shown; do specific regions (corners vs center) exhibit statistically different KAG patterns?

- Minor order limitation: Results are restricted to k ≤ 3 due to numerical/stability concerns; can numerically stable methods (e.g., pivoted decompositions or log-determinants) extend analysis to higher k and confirm scaling trends?

- Sign information loss: Minors are analyzed by absolute value only; does the sign or orientation of minors carry informative structure (e.g., consistent across classes or layers)?

- Sampling bias: Minor distributions are estimated via random sampling (up to 10k combinations); how sensitive are PR/KL/RR to sampling strategy, sample size, and deterministic seeds?

- “Zero rows” hallmark: The paper emphasizes minors and alignment but does not quantify vanishing Jacobian rows; how prevalent are locally constant hidden units and how do they vary across inputs and training?

- Metric robustness: PR can depend on the number and scale of sampled minors; can alternative heavy-tail measures (e.g., tail index, Gini coefficient) or normalized PR variants improve comparability across settings?

- Alignment metric variance: RR exhibits high variance and one-seed outliers; can more stable alignment observables (e.g., subspace angles, coherence measures) corroborate alignment claims?

- Interpretability: Which neurons and pixels contribute to dominant minors; can we map large minors to meaningful input structures (strokes, edges) or learned features?

- Augmentation breadth: Only small translations (±4 px) are tested; how do rotations, scaling, elastic distortions, noise, cutout, and stronger affine transforms modulate KAG?

- Convolutional locality: In CNNs, locality is inductive-bias-driven; does scale-agnostic KAG persist or differ when spatial structure is explicit rather than implicit (as in MLPs)?

- Preprocessing sensitivity: Do choices like input normalization, whitening, or pixel intensity scaling affect KAG emergence or strength?

- Sample size effects: How does training set size (subsampling MNIST) influence KAG, and does KAG predict sample efficiency or data hunger?

- Output-layer analysis: The Jacobian of second hidden layer w.r.t. inputs is analyzed; what geometric signatures appear in the Jacobian of logits w.r.t. inputs?

- Closeness to KA ideal: Can the “one nonzero per column” ideal be quantified directly (e.g., sparsity patterns, column-wise support size) and tracked during training?

- Global vs local consistency: Do distance-constrained minors reveal consistent global geometry across different inputs, or is global KAG highly input-dependent?

- Seed sensitivity: With only 5 seeds and noted outliers, how stable are KAG conclusions across more seeds and different random states?

- Theoretical underpinning: What mechanisms in gradient descent and loss landscapes drive KAG emergence; can we formalize implicit biases that favor KA-like Jacobians?

- Reproducibility artifacts: Full code and data links are not provided in the text; standardized benchmarks and open implementations would enable independent verification of numerical subtleties (e.g., AD precision, determinant stability).

Glossary

- AdamW: An optimizer that decouples weight decay from the gradient-based update, improving generalization over Adam. "Models are trained using AdamW for 200 epochs"

- Alignment: A structured correlation in the Jacobian not preserved under generic rotations, indicating preferred bases in learned representations. "Alignment: The Jacobian structure exhibits non-generic alignment that is not preserved under random orthogonal rotations"

- Automatic differentiation: A computational technique to obtain derivatives programmatically, used here to compute Jacobians efficiently. "using PyTorch's vectorized automatic differentiation."

- Cosine annealing: A learning-rate schedule that follows a cosine decay curve over training. "LR schedule & Cosine annealing"

- Euclidean ball sampling: A spatial sampling method selecting pixels within a fixed Euclidean radius to probe local geometric structure. "First, for Euclidean ball sampling, we select varying radii pixels"

- GELU: Gaussian Error Linear Unit, an activation function that smoothly weights inputs by their value under a Gaussian. "We train 2-layer MLPs with GELU activations on MNIST digit classification"

- Implicit regularization: The tendency of optimization dynamics (e.g., gradient descent) to favor certain solutions even without explicit penalties. "connect to broader questions about implicit regularization and the geometry of loss landscapes."

- Jacobian: The matrix of first-order partial derivatives mapping input perturbations to changes in hidden representations. "Analyzing the Jacobian matrix of the inner map"

- Kaiming He initialization: A variance-preserving weight initialization tailored for ReLU-like activations. "We use Kaiming He initialization \citep{he2015delving} for all weight matrices:"

- KL divergence: A measure of how one probability distribution diverges from another, used to quantify training-induced shifts in minor distributions. "KL Divergence: We measure how much the minor distribution changes during training:"

- Kolmogorov-Arnold geometry (KAG): A structured pattern in learned representations linked to the Kolmogorov-Arnold superposition theorem, characterized by sparse and aligned Jacobians. "dubbed Kolmogorov-Arnold geometry (KAG) in \citet{freedman2025spontaneous}"

- Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN): Architectures that explicitly implement KA-style representations via learnable univariate functions. "The connection to neural networks is one-to-one in the KAN construction \citep{liu2024kan}"

- Kolmogorov-Arnold theorem: A result stating any multivariate continuous function can be represented as sums and compositions of univariate continuous functions. "The Kolmogorov-Arnold (KA) theorem states that any continuous function of multiple variables can be exactly represented as a finite composition and superposition of continuous functions of a single variable."

- Loss landscape: The high-dimensional surface defined by the loss function over parameters, whose geometry influences optimization dynamics. "implicit regularization and the geometry of loss landscapes."

- Minor (matrix minor): The determinant of a k×k submatrix of the Jacobian, used to quantify multi-dimensional sensitivity (k-volume). "we compute determinants (minors) for "

- Minor concentration (MC): A phenomenon where the distribution of Jacobian minors is sharply peaked at zero yet heavy-tailed, indicating sparse but strong interactions. "Minor concentration (MC): The distribution of determinants (minors) of has a large spike at zero , but is simultaneously heavy-tailed"

- Neural collapse: A late-training regime where class representations become highly structured, e.g., class means form a simplex configuration. "The relationship to neural collapse \citep{papyan2020prevalence} is particularly intriguing."

- Overparameterized networks: Models with more parameters than strictly needed to fit the training data, often exhibiting distinctive optimization geometry. "how gradient descent organizes representations in overparameterized networks"

- Participation ratio (PR): A concentration metric defined as ||m||2 / ||m||1 over minor magnitudes, capturing heavy-tailedness. "Participation Ratio (PR): For a set of minor values , the participation ratio is:"

- RandomAffine: A data-augmentation operator applying random affine transforms (e.g., translations) to images. "using spatial data augmentation with RandomAffine transformations (translation 4 pixels horizontal/vertical) applied during training."

- Random orthogonal rotations: Transformations by random orthogonal matrices used to test whether geometric structure depends on specific bases. "not preserved under random orthogonal rotations"

- Rotation Ratio (RR): A metric comparing PR before and after random orthogonal rotations to detect alignment. "Rotation Ratio (RR): To test whether Jacobian structure is aligned with the neuron bases axis of and , we apply random orthogonal transformations"

- SO(h): The special orthogonal group of h×h rotation matrices (determinant 1), representing rotations in h-dimensional space. "where "

- Simplex configurations: Highly symmetric arrangements of class means in representation space characteristic of neural collapse. "with class means collapsing toward symmetric simplex configurations."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now using the paper’s methods (Jacobian-based analysis, minor statistics, PR/KL/RR metrics) and findings (spontaneous, scale-agnostic KAG; sensitivity of KAG strength to training data diversity).

- KAG telemetry for training diagnostics (software/MLOps; healthcare, finance, robotics)

- Use PR, KL, and RR computed on Jacobians at regular intervals to monitor representational geometry during training, flagging unusual “frustration” or overfitting when PR spikes or when RR shows excessive alignment.

- Tools/workflows: PyTorch-based “KAG Monitor” module that computes layer-wise Jacobians and minor statistics every N epochs; dashboards tracking PR/KL/RR trends versus accuracy and loss.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires automatic differentiation and GPU time to compute Jacobians; current signal validated in 2-layer MLPs on MNIST—thresholds need task/architecture-specific calibration.

- Augmentation tuning via geometric feedback (software, vision; healthcare imaging, robotics)

- Adjust spatial augmentation intensity using PR changes: the paper shows augmented training lowers PR ~30–40%; practitioners can target a PR range to avoid geometric “frustration” while maintaining accuracy.

- Tools/workflows: “Augmentation Tuner” that adapts RandomAffine and other transforms based on PR targets; A/B comparisons guided by geometry.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Empirically observed on MNIST; generalization to other tasks/architectures likely but not yet proven; compute overhead for Jacobian analysis.

- Early-warning indicators of data insufficiency or distribution narrowness (software/MLOps; industry)

- High PR with stable accuracy suggests the model is organizing representations in extreme geometry due to limited variability (“frustration”). Use as a trigger to broaden data or augmentations.

- Tools/workflows: Automated alerts when PR exceeds baseline bands relative to random initialization; pipeline step to expand datasets or diversify augmentation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Correlational evidence; policy for thresholds should be validated per domain.

- Layer-wise feature pruning and efficiency (edge AI; software)

- Exploit “zero rows” and low-gradient hidden units to prune redundant neurons or compress early layers without large drops in accuracy.

- Tools/workflows: Gradient-norm screening of hidden units; post-training pruning passes guided by Jacobian row norms; lightweight re-finetune.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Safe pruning depends on task sensitivity; measure at multiple inputs to avoid pruning units that are important on rare modes.

- Spatial sensitivity mapping for interpretability (healthcare imaging; robotics; education)

- Use Jacobian columns and minor magnitudes to map which input regions (local patches or widely separated pixels) most influence internal representations, complementing saliency maps.

- Tools/workflows: “Spatial KAG Analyzer” producing per-region PR profiles and sensitivity maps at different radii or minimum-distance constraints.

- Assumptions/dependencies: MNIST findings show scale-agnosticity; extension to complex images expected but must be tested; interpretability remains qualitative.

- Architecture/training regime selection with geometric criteria (software; academia)

- Compare models by KAG metrics to select configurations that produce more stable or desirable geometry (e.g., lower PR under augmentation, stronger early-layer organization).

- Tools/workflows: Benchmark suites reporting PR/KL/RR alongside accuracy and latency; model cards including geometry profiles.

- Assumptions/dependencies: The utility of geometry as a selection criterion is task-dependent; causality (geometry → generalization) not yet established.

- Teaching and reproducible research exercises (academia; education)

- Use the open methodology to teach representational geometry: computing Jacobians, minors, PR/KL/RR, spatial sampling, and rotation tests in lab courses.

- Tools/workflows: Notebook kits with vectorized AD and minor sampling; assignments comparing standard vs augmented training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires access to GPU or small-scale CPU demos; results strongest in early layers and small networks.

Long-Term Applications

The following applications are promising but require further research, scaling, or development (e.g., causality tests, larger datasets, modern architectures, and efficiency improvements).

- Geometry-regularized training objectives (software; healthcare, finance, robotics)

- Add loss terms that encourage or discourage specific KA signatures (e.g., controlling PR, penalizing extreme RR) to improve generalization, stability, or robustness.

- Potential products: “KA Regularizer” library; geometry-aware schedulers that adjust regularization over training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Causal benefits not yet proven; must avoid collapsing useful representation diversity.

- Geometry-aware architectures and feature routing (software; edge AI; energy-constrained devices)

- Design layers that structurally favor KA-like Jacobians (e.g., per-column sparsity, learnable univariate transforms as in KAN) for efficiency and interpretability.

- Potential products: “KAG-MLP” blocks, hybrids with KAN; dynamic gating enforcing near-single-activity per column.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Need validation on deep CNNs/Transformers and large datasets; trade-offs with accuracy and flexibility.

- Robustness and adversarial defense via Jacobian control (software; policy; safety-critical sectors)

- Use geometry constraints to limit vulnerability (e.g., controlling Jacobian norms and minor concentration to reduce adversarial sensitivity).

- Potential products: Defense modules that monitor and cap PR/gradient norms; certification tests including RR/PR profiles.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires rigorous red-teaming and formal analysis; must avoid oversimplifying representations.

- Data-centric AI: geometry-guided dataset design and curricula (software; policy; industry)

- Use PR/KL trajectories to quantify dataset diversity, guide acquisition, and schedule augmentations/curricula to shape geometry throughout training.

- Potential products: “Geometry Curriculum Designer” that modulates data difficulty/variety when PR patterns become extreme.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Needs validated links between geometry trajectories and learning outcomes across domains.

- Model fingerprinting, auditing, and drift detection (software; compliance; security)

- Treat a model’s geometry profile (PR/KL/RR across layers) as a fingerprint for provenance, tamper detection, or drift monitoring.

- Potential products: Audit tools that log geometry baselines and alert on deviations; regulatory reporting standards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Must establish robustness of profiles across retrains and updates; privacy impacts to be considered.

- Cross-architecture generalization and large-scale validation (academia; industry)

- Extend KAG analysis to CNNs, ResNets, transformers, and multimodal models on ImageNet, medical imaging, language modeling, and time series.

- Potential products: Unified “Geometry Dashboard” integrated into major training frameworks; lightweight approximations for large models.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Significant compute; efficient Jacobian estimation (Hessian-vector methods, low-rank approximations) likely needed.

- Interplay with neural collapse and late-phase training control (academia; software)

- Investigate how early-layer KAG dynamics relate to class-level geometry (simplex structures) and exploit this to time regularization, early stopping, or fine-tuning phases.

- Potential products: Phase-aware trainers that pivot strategies when geometry indicates impending collapse or saturation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires joint, multi-layer geometry tracking and causal experiments.

- Hardware acceleration for geometry metrics (semiconductors; software/hardware co-design)

- Develop kernels or accelerators for Jacobian/minor computation and rotation sampling to make geometry monitoring practical at scale.

- Potential products: “Geometry Ops” libraries optimized for GPUs/TPUs; firmware support for vectorized AD patterns.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Needs standardization of metrics and workflows; benefits increase with model size and training frequency.

- Safety and policy standards (policy; healthcare/finance/regulatory)

- Incorporate geometry-based diagnostics into model documentation and audits (e.g., PR/KL/RR bands as part of model cards; thresholds for deployment in safety-critical contexts).

- Potential products: Draft guidelines and benchmarks for geometry reporting; compliance pipelines integrating KAG checks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Evidence base linking geometry to reliability/fairness must be established; sector-specific calibration required.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.