ROOT: Robust Orthogonalized Optimizer for Neural Network Training (2511.20626v1)

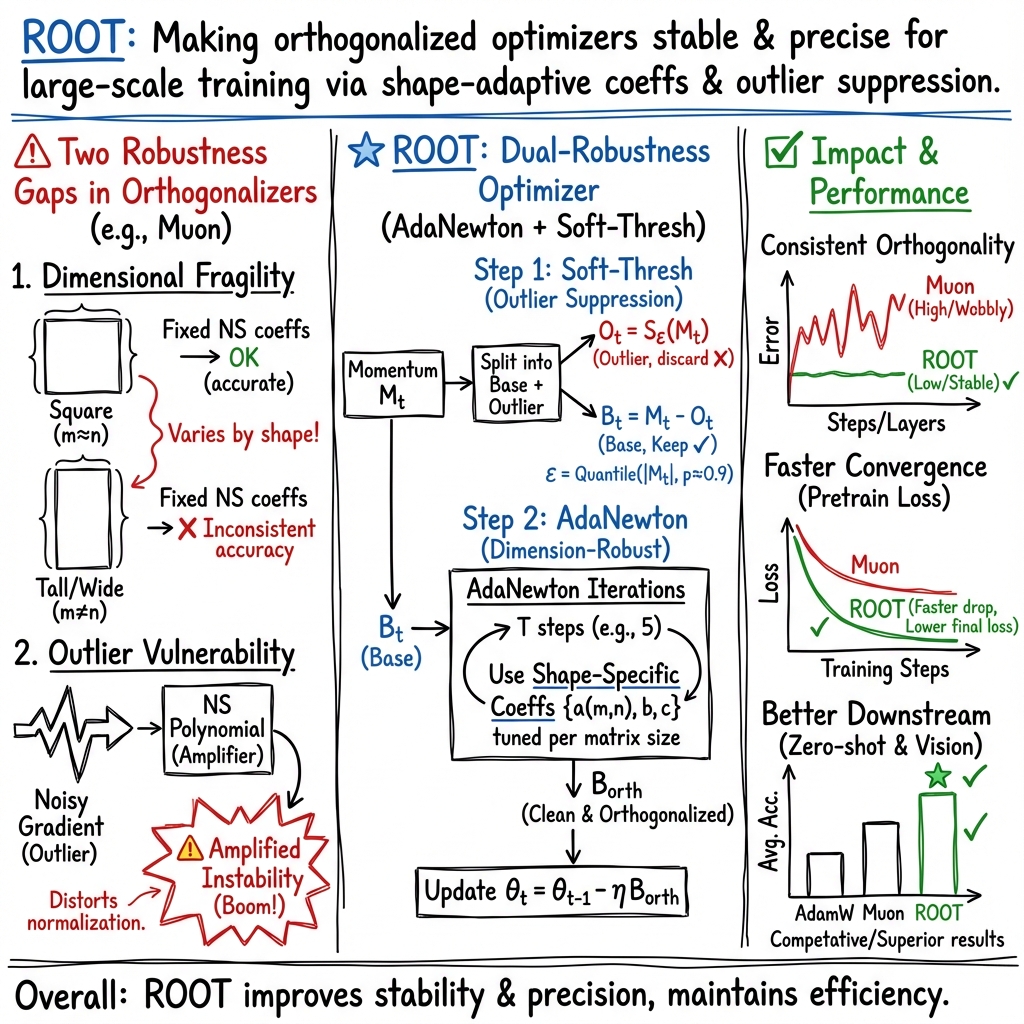

Abstract: The optimization of LLMs remains a critical challenge, particularly as model scaling exacerbates sensitivity to algorithmic imprecision and training instability. Recent advances in optimizers have improved convergence efficiency through momentum orthogonalization, but suffer from two key robustness limitations: dimensional fragility in orthogonalization precision and vulnerability to outlier-induced noise. To address these robustness challenges, we introduce ROOT, a Robust Orthogonalized Optimizer that enhances training stability through dual robustness mechanisms. First, we develop a dimension-robust orthogonalization scheme using adaptive Newton iterations with fine-grained coefficients tailored to specific matrix sizes, ensuring consistent precision across diverse architectural configurations. Second, we introduce an optimization-robust framework via proximal optimization that suppresses outlier noise while preserving meaningful gradient directions. Extensive experiments demonstrate that ROOT achieves significantly improved robustness, with faster convergence and superior final performance compared to both Muon and Adam-based optimizers, particularly in noisy and non-convex scenarios. Our work establishes a new paradigm for developing robust and precise optimizers capable of handling the complexities of modern large-scale model training. The code will be available at https://github.com/huawei-noah/noah-research/tree/master/ROOT.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What this paper is about

This paper introduces a new way to train large AI models (like chatbots) more safely and quickly. It focuses on the “optimizer,” which is the set of rules that decides how the model should adjust itself to get better. The new method is called ROOT (Robust Orthogonalized Optimizer). ROOT aims to keep training stable, even when things get noisy or tricky, and to make progress faster than popular methods like AdamW and Muon.

The main questions the paper asks

The authors noticed two big problems with modern training methods and set out to fix them:

- Many recent optimizers (like Muon) “clean up” the model’s update directions using the same settings for every layer. But different layers in a big model have different shapes and sizes, and one fixed setting doesn’t work equally well for all of them.

- During training, a few “outlier” examples can create very large, noisy updates (like a sudden spike). These outliers can throw the model off-course and make training unstable.

So the questions are: Can we make the “direction cleanup” step precise for every layer size? And can we filter out extreme noise without losing useful information?

How the method works (in simple terms)

Think of training a model like hiking across a huge, bumpy landscape in fog. The optimizer is your guide. A good guide picks steady directions and avoids getting pushed around by sudden gusts of wind (noise).

This paper improves the guide in two ways.

1) Better “direction cleanup” for every layer size

Modern optimizers sometimes use a process called “orthogonalization” to turn messy update directions into clean, well-spaced ones (like aligning your steps to north–south and east–west so you don’t slide diagonally by accident). Muon does this using a repeated math recipe (called the Newton–Schulz iteration) with fixed knobs (three numbers a, b, c).

ROOT changes this by making those knobs adaptive:

- Different layers (tables of numbers with different shapes) need slightly different settings to get the same level of accuracy.

- ROOT learns fine-tuned settings for each layer size, so the “cleanup” is precise everywhere, not just on average.

Analogy: If you bake cakes in pans of different sizes, you shouldn’t use the exact same recipe timings for all pans. ROOT adjusts the recipe based on the pan size so every cake comes out right.

2) Gentle filtering of extreme noise (outliers)

Sometimes, parts of the training signal are way too large—like a sudden loud pop in an audio recording. Many methods try to clip (cut off) these spikes, but hard clipping can be harsh and lose useful details.

ROOT uses “soft-thresholding,” a smooth version of clipping:

- If a number is small, keep it as is.

- If it’s very large, nudge it down toward a safer level rather than slicing it off.

- The result is a cleaner signal that still points in the right direction.

Analogy: It’s like using a smart volume control that turns down only the painful spikes without muting the music.

Putting it together:

- First, ROOT separates the clean part of the update from the outlier part (using soft-thresholding).

- Then, it applies the improved “direction cleanup” only to the clean part.

- Finally, it updates the model with these stable, well-aimed steps.

What they found and why it matters

In their tests on LLM training and standard benchmarks, the authors report:

- More accurate “direction cleanup” across all layer sizes: ROOT’s adaptive settings reduced errors compared to fixed settings, keeping updates reliable during the entire training.

- Faster and more stable training: ROOT reached lower training loss (it learned better, faster), especially when the data was noisy or the learning landscape was very bumpy.

- Better or competitive scores on common language benchmarks: Compared to AdamW and Muon, ROOT often scored higher on tasks like HellaSwag, PIQA, and others.

- Works beyond language: ROOT’s noise-filtering also improved results in an image classification test, suggesting it’s useful in vision tasks too.

- Practical tuning tips: A dynamic threshold that keeps the top 10% largest values as “outliers” (around the 90th percentile) gave a good balance between filtering noise and keeping helpful signal.

These results matter because training big models is expensive and delicate—instability can waste time and money. ROOT speeds things up and makes training more reliable.

Why this could be important in the long run

Training future AI systems will keep getting larger and more complex. ROOT shows a new way to build optimizers that are both precise and tough:

- Precision: Adjust the “direction cleanup” to match each layer’s size so every part of the model gets equally good treatment.

- Toughness: Smoothly tame extreme noise before it can derail training.

If widely adopted, this could help companies and researchers train better models faster, with fewer crashes or slowdowns—making powerful AI more accessible and dependable.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to guide follow-up research:

- Lack of formal, rigorous convergence guarantees for the adaptive Newton-Schulz iteration with learned, dimension-specific coefficients, including precise stability domains and conditions on singular value spectra under which the iteration remains contractive.

- Unclear methodology for learning the coefficients

a(m,n), b(m,n), c(m,n): no explicit optimization algorithm, objective, or training procedure (online vs. offline, per-layer vs. global) is specified; reproducible details (data used, optimization solver, regularization) are missing. - Inconsistency between claims of “jointly learning” coefficients during training and later “offline calibration”; the paper does not clarify when and how coefficients are updated, frozen, or transferred between runs or architectures.

- No analysis of how shape-specific coefficients generalize to unseen matrix shapes (e.g., new aspect ratios from model reconfigurations, fine-tuning adapters, or parameter-efficient modules) or to non-standard parameter types (embeddings, layer norms, convolutions).

- Fixed iteration count (5 steps) is assumed throughout; there is no paper of iteration-count adaptivity, accuracy–compute trade-offs, or dynamic stopping criteria based on residual/error estimates at runtime.

- No comparison against newer or stronger baselines beyond AdamW and Muon (e.g., AdaMuon, AdaGO, CANS/Chebyshev variants, Dion/power iteration, Shampoo/K-FAC), leaving unclear where ROOT sits in the current optimizer landscape.

- Absence of wall-clock, memory, and communication overhead analysis for

AdaNewtonversus Muon/AdamW, especially under distributed training; no profiling on GPUs vs. NPUs or under mixed-precision and activation checkpointing. - Theoretical section provides only a high-level minimax inequality (

E(m,n) ≤ E_std) without quantifying the magnitude of improvement, assumptions on spectral distributionsS(m,n), or how these distributions are estimated reliably during training. - Orthogonalization error improvements are demonstrated early (first 10k steps) but not tracked across longer trajectories or multiple training phases; no link is established between lower orthogonalization error and downstream metrics (perplexity, generalization) with statistical rigor.

- Reported training and benchmark gains are small; no statistical significance, variance across seeds, or sensitivity analyses (e.g., different datasets, sequence lengths, batch sizes) are provided.

- Proximal soft-thresholding is motivated but not compared against established baselines (global norm clipping, per-layer norm clipping, adaptive clipping schedules); lack of ablations on alternative robustification methods (Huber, Tukey, quantile normalization, group-wise shrinkage).

- Outlier modeling is element-wise and ignores structure (per-row/column/group/channel); it remains unknown whether structured outlier suppression (e.g., block-wise or subspace-wise) would better preserve informative gradients while removing noise.

- The choice and schedule of the percentile threshold

p(optimal at 0.90 in one setting) is empirical; there is no paper of per-layer, per-parameter, or time-varying thresholding, nor principled tuning (e.g., linkingεtoλin the proximal objective) grounded in theory. - The proximal formulation includes a constraint

|B| ≤ Tbut does not define the norm, selection ofT, or how it interacts with optimizer state (momentum, weight decay) and mixed-precision scaling; potential bias introduced by discardingO_tis not quantified. - No analysis of false positives/negatives in outlier detection: when does soft-thresholding remove useful signal, and what is the impact on convergence speed, final accuracy, and generalization?

- Interaction effects between orthogonalization and soft-thresholding are not dissected: do they help or hinder each other under different noise regimes, tasks, or layer types? Are there regimes where one component suffices?

- Claims about improved stability (e.g., “exploding attention logits”) are qualitative; the paper does not provide quantitative stability metrics (gradient norms, logit statistics, loss spikes) or failure cases under stress (noisy data, extreme batch sizes).

- Evaluation is limited to a 1B model trained for a single epoch on FineWeb-Edu subsets and zero-shot benchmarks; scalability to larger models (≥7B), longer training (hundreds of billions of tokens), instruction/finetuning regimes, and RLHF settings remains unexplored.

- Generalization beyond language tasks is assessed only on a small ViT for CIFAR-10 with soft-thresholding alone; combining

AdaNewton+ soft-thresholding on larger vision models or other modalities (speech, multimodal) is not evaluated. - ROOT is tested on Ascend NPUs with bespoke infrastructure; portability, reproducibility, and performance on commodity GPUs/TPUs are not addressed. Code availability is promised but not present, limiting external validation.

- No guidance is provided on integrating ROOT with popular training toolchains (DeepSpeed, Megatron-LM), optimizer state checkpointing, or distributed optimizer partitioning—practical steps for broad adoption are missing.

- Lack of failure-mode analysis: under which spectra, data distributions, or hyperparameter settings does

AdaNewtondiverge, slow down, or destabilize training? Diagnostic tools and safeguards are not specified.

Glossary

- AdaGrad-style step sizes: Adaptive per-parameter step sizes based on accumulated squared gradients. "AdaGO (Zhang et al., 2025) combines orthogonal directions with AdaGrad-style step sizes."

- Adaptive Newton-Schulz iteration (AdaNewton): A Newton-Schulz iteration whose coefficients are adapted to matrix dimensions to improve orthogonalization accuracy. "we propose an adaptive Newton-Schulz iteration (AdaNewton) with fine-grained, dimension-specific coefficients."

- Attention-mask-reset strategy: A technique to reset attention masks so that tokens from different documents do not attend to each other. "An attention-mask-reset strategy (Chen et al., 2025) is also used to prevent self-attention between different documents within a sequence."

- Chebyshev polynomials: Special polynomials used to accelerate iterative methods over specified spectral intervals. "CANS (Grishina et al., 2025) utilizes Chebyshev poly- nomials to accelerate the convergence of the orthogonaliza- tion process over spectral intervals."

- Cosine learning rate schedule: A learning-rate schedule that decays following a cosine curve from a peak to a minimum. "We employ a cosine learning rate schedule that decays to 10% of the peak learning-rate, following a warm-up phase of 2,000 steps."

- Frobenius norm: A matrix norm equal to the square root of the sum of the squares of all entries. "the optimization objective is to minimize the Frobenius norm distance to the identity matrix:"

- Isomorphic update matrices: Update matrices with orthogonal structure (e.g., UVT) that maintain equal magnitude across directions, encouraging diverse optimization paths. "This orthogonalization process pro- motes isomorphic update matrices, which encourages the network to explore diverse optimization directions rather than converging along a limited set of dominant pathways."

- Kronecker-factored preconditioners: Curvature approximations built from Kronecker products of smaller matrices to precondition gradients efficiently. "leverage Kronecker-factored preconditioners to capture parameter geometry."

- Mean squared error (MSE): The average of squared differences used here to quantify orthogonalization error. "the mean squared error (MSE) of the orthogonal approxima- tion varies dramatically with matrix shape."

- Momentum orthogonalization: Enforcing orthogonality on momentum matrices to regulate update geometry and improve stability. "improve convergence efficiency through momen- tum orthogonalization but suffers from two key robustness limitations"

- Newton-Schulz iteration: An iterative matrix method to approximate inverses and roots, used here to produce orthogonalized momentum updates. "Muon employs a Newton-Schulz iteration (Bernstein & Newhouse, 2024; Higham, 2008; Guo & Higham, 2006) to orthogonalize the momentum matrix"

- Orthogonalization-based optimizers: Optimizers that produce updates by transforming momentum or gradients toward orthogonality instead of relying on element-wise adaptations. "The orthogonalization-based optimizers, e.g., Muon (Jordan et al., 2024), address the optimization of neural network parameters that exhibit a matrix structure."

- Outlier-induced gradient noise: Large, anomalous gradient components from rare samples that can distort updates and destabilize training. "height- ened sensitivity to outlier-induced gradient noise, which is a common phenomenon in large-scale training"

- Proximal optimization: Optimization augmented with a proximal term to enforce regularization or constraints, often enabling robust handling of outliers. "we incorpo- rate a proximal optimization term that suppresses outlier- induced gradient noise via soft-thresholding"

- Proximal operator: The operator that yields the solution to a proximal subproblem; for L1-norm it is soft-thresholding. "characterized by the proximal operator for the L1-norm, which yields the soft-thresholding function"

- Quantile-based threshold: A threshold defined by a percentile (quantile) of the value distribution, used to adapt clipping to current gradient scales. "we employ a dynamic, percentile-based threshold Et = Quantile(|Mt], p) to adapt to the evolving gradient scale."

- Randomized SVD: A fast, approximate singular value decomposition computed via randomized algorithms. "LiMuon (Huang et al., 2025) leverages randomized SVD"

- Singular value decomposition (SVD): A matrix factorization X = UΣVT that exposes singular values and orthogonal directions. "Considering the singular value decomposition (SVD) of Mt = UEVT, this transformation yields UVT,"

- Soft-thresholding: The L1 proximal operator that shrinks values toward zero by a threshold, suppressing outliers smoothly. "which yields the soft-thresholding function (Tibshirani, 1996; Donoho, 2002):"

- Spectral calibration strategy: A procedure to choose iteration coefficients by fitting to the singular-value (spectral) distributions observed during training. "Spectral Calibration Strategy. To determine the optimal coefficients {a, b, c} for ROOT (AdaNewton), we perform offline optimization using singular value distributions of momentum matrices with varying dimensions"

- Spectral norm: The matrix/operator norm equal to the largest singular value, defining geometry for steepest-descent in Muon-like methods. "which theoretically corresponds to performing steepest descent under the spec- tral norm (Li & Hong, 2025; Kovalev, 2025)."

- Steepest descent under the spectral norm: A descent method where the step direction is chosen to be steepest with respect to the spectral norm geometry. "which theoretically corresponds to performing steepest descent under the spec- tral norm (Li & Hong, 2025; Kovalev, 2025)."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The findings and methods in ROOT enable several drop-in improvements to existing ML pipelines, especially where training instability and noisy gradients are common.

- Drop-in optimizer for LLM pretraining and fine-tuning — sectors: software/AI, cloud providers, enterprise ML

- Tools/workflows: replace AdamW/Muon with ROOT in PyTorch/JAX/DeepSpeed pipelines; keep 5 Newton-Schulz steps; use p≈0.90 quantile soft-threshold as a robust default; cache per-layer dimension-specific coefficients learned offline.

- Assumptions/dependencies: code availability; integration for 2D weight tensors (continue using AdamW for 1D params like norms/biases if needed); validation on your model’s matrix shapes; mixed-precision compatibility.

- Stabilizing noisy regimes (RLHF, preference modeling, DPO/SFT with imperfect data) — sectors: foundation model training, safety, content platforms

- Tools/workflows: enable ROOT’s soft-thresholded momentum to suppress heavy-tailed gradient spikes without discarding signal; combine with existing gradient clipping; reduce loss spikes and exploding attention logits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: percentile threshold tuning (start at p=0.90; adjust per task); ensure logging of gradient norms to verify tail suppression.

- Faster convergence to target loss (reduced training time/cost) — sectors: cloud/compute, MLOps, sustainability

- Tools/products: training schedulers that stop early when loss plateaus sooner; carbon dashboards crediting optimizers that reduce steps; budgeting tools that reflect expected step savings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: gains vary by model/data; measure on a small pilot to calibrate expected step reductions before committing large runs.

- More reliable distributed training (fewer instability-induced restarts) — sectors: HPC, AIOps/SRE for ML platforms

- Tools/workflows: pair ROOT with distributed optimizers (e.g., Dion) to lessen sensitivity to layer shape and gradient outliers; add monitors on quantile thresholds and orthogonalization error to trigger alerts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: compatible collective ops; stable coefficient lookup per shard; minimal communication overhead from any added telemetry.

- Robust training for small vision and multimodal models — sectors: robotics, manufacturing, edge/embedded, automotive

- Tools/workflows: apply ROOT to 2D weight matrices in ViTs while keeping 1D params on AdamW; use the same soft-thresholding for momentum; adopt p in [0.85, 0.95] per the task’s noise profile.

- Assumptions/dependencies: improvements beyond CIFAR-10 need validation on your datasets; quantify any overhead of orthogonalization vs. accuracy gains.

- Data quality triage via “gradient outlier telemetry” — sectors: data engineering, MLOps, data governance

- Tools/workflows: log the soft-thresholding mask/Ot to identify problematic samples or shards; route flagged batches to curation pipelines; prioritize reweighting or deduplication.

- Assumptions/dependencies: linkage from gradients to sample IDs (e.g., per-sample gradient or microbatch mapping); privacy constraints for logging.

- Default optimizer baselines for academic benchmarks and courses — sectors: academia, education

- Tools/workflows: include ROOT as a baseline in optimizer studies; use its dimension-specific coefficients to teach matrix-aware optimization and spectral effects.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reproducible coefficient calibration (Mixed 1:3 strategy) and public code for didactic use.

- Safer training guardrails for production LLMs — sectors: safety, reliability engineering

- Tools/workflows: set conservative defaults (e.g., p=0.90, capped learning-rate warmups) and continuously track orthogonalization relative error vs. SVD on small probes; auto-fallback to higher thresholds if instability rises.

- Assumptions/dependencies: lightweight probe computation budget; policies for automated parameter adjustments.

Long-Term Applications

Some opportunities will benefit from further research, scaling, or systems integration before wide deployment.

- Hardware-accelerated kernels for ROOT — sectors: semiconductors, cloud accelerators (TPU/NPU/GPU)

- Tools/products: fused Newton–Schulz with adaptive coefficients; fast quantile computation for soft-thresholding; vendor libraries (cuDNN/XLA/Ascend) with dimension-aware coefficient tables.

- Assumptions/dependencies: vendor buy-in; stable ABI across frameworks; clear performance wins in representative workloads.

- Online/learned per-layer coefficients — sectors: AutoML, optimizer research

- Tools/workflows: jointly learn {a,b,c} per layer during training (meta-parameters) with regularization; schedule updates based on spectral drift; integrate into hyperparameter search.

- Assumptions/dependencies: stability of meta-optimization; low overhead for coefficient updates; safeguards against overfitting to transient spectra.

- Federated and Byzantine-robust training — sectors: mobile, healthcare, finance

- Tools/workflows: apply soft-thresholded momentum aggregation at the server to mitigate malicious or anomalous clients; combine with robust aggregation (e.g., median/trimmed mean).

- Assumptions/dependencies: privacy-preserving telemetry; convergence analysis under non-i.i.d. data and communication constraints.

- On-device continual personalization — sectors: smartphones, IoT, AR/VR

- Tools/products: efficient ROOT variants for low-power NPUs; dynamic thresholds based on local gradient statistics; safer on-device updates under noisy user data.

- Assumptions/dependencies: memory-efficient implementations; energy budgets; secure rollback on instability.

- Sector-specific robust learning under label noise — sectors: healthcare imaging, scientific ML, cybersecurity

- Tools/workflows: combine ROOT with noise-robust losses and curriculum learning to handle heavy-tailed/noisy labels; track outlier masks to inform relabeling or expert review.

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain validation and regulatory approval; explainability requirements for clinical or regulated contexts.

- Curriculum/data pipeline driven by optimizer signals — sectors: data platforms, AutoDL

- Tools/products: adaptive sampling/reweighting that deprioritizes batches repeatedly flagged as gradient outliers; schedule harder examples as stability improves.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable mapping from outlier statistics to data units; guardrails to avoid discarding rare-but-valuable samples.

- Framework defaults and standards for robust, energy-aware training — sectors: policy, standards bodies, sustainability

- Tools/workflows: best-practice guidelines recommending robust optimizers for mixed-precision large-scale training; reporting templates that attribute energy savings to optimizer choice.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consensus across labs; standardized measurement of “steps-to-target-loss” and carbon intensity.

- Training orchestration products with optimizer intelligence — sectors: enterprise ML platforms

- Tools/products: controllers that select between AdamW/Muon/ROOT per phase; maintain coefficient caches per layer shape; auto-tune quantile thresholds via bandits; rollback on instability.

- Assumptions/dependencies: telemetry integration; policy for automated changes in regulated environments.

- Safety-critical online adaptation (robotics/AVs) — sectors: robotics, autonomous systems

- Tools/workflows: use ROOT for on-policy updates with sensor outliers; limit update magnitude via proximal thresholding to preserve stability in the control loop.

- Assumptions/dependencies: rigorous verification and real-time constraints; simulation-to-real validation; fail-safe mechanisms.

Notes on cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies:

- ROOT’s benefits depend on availability of per-layer dimension-specific coefficients; if not learned online, an offline “Mixed 1:3” calibration (real+random matrices) is a practical interim solution.

- Soft-thresholding percentile p is task-dependent; p≈0.90 worked well in LLM pretraining ablations but should be tuned for new modalities.

- ROOT primarily targets 2D weight matrices; 1D parameters can remain on AdamW without negating gains.

- Any expected cost/energy savings should be validated on your stack, as wins depend on model scale, data noise, precision settings, and distributed topology.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.