AMB3R: Accurate Feed-forward Metric-scale 3D Reconstruction with Backend (2511.20343v1)

Abstract: We present AMB3R, a multi-view feed-forward model for dense 3D reconstruction on a metric-scale that addresses diverse 3D vision tasks. The key idea is to leverage a sparse, yet compact, volumetric scene representation as our backend, enabling geometric reasoning with spatial compactness. Although trained solely for multi-view reconstruction, we demonstrate that AMB3R can be seamlessly extended to uncalibrated visual odometry (online) or large-scale structure from motion without the need for task-specific fine-tuning or test-time optimization. Compared to prior pointmap-based models, our approach achieves state-of-the-art performance in camera pose, depth, and metric-scale estimation, 3D reconstruction, and even surpasses optimization-based SLAM and SfM methods with dense reconstruction priors on common benchmarks.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Explaining “AMB3R: Accurate Feed-forward Metric-scale 3D Reconstruction with Backend”

Overview

This paper introduces AMB3R, a computer program that can build accurate 3D models of the real world from regular photos or videos. It does this quickly, in a single pass (called “feed-forward”), and it knows the real size of things (called “metric scale,” so a meter in the model equals a meter in real life). AMB3R also works for related tasks like tracking how a camera moves (visual odometry and SLAM) and building big 3D models from many photos (Structure from Motion), all without extra fine-tuning or slow optimization steps.

Key Objectives

The paper sets out to answer a few simple questions:

- Can we make a fast, one-pass 3D system that still reasons carefully about real-world geometry?

- Can this system recover the true size and scale of scenes (not just relative depth)?

- Can it do more than just depth—like estimate camera positions, build full 3D models, and run on long videos—without extra training or fine-tuning?

- Can it beat or match the accuracy of slower, optimization-heavy methods?

Methods (with simple explanations)

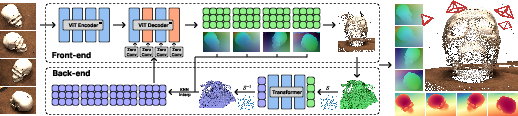

Think of AMB3R like a two-part team: a front-end and a back-end.

1) Front-end: “Seeing and guessing”

- The front-end (based on a model called VGGT) looks at the images and produces:

- Pointmaps: For each pixel in an image, it guesses where that point is in 3D space. Imagine every pixel has an arrow pointing to a 3D location.

- Features: Useful information about the geometry and appearance that helps later steps.

- Metric scale head: The front-end usually predicts shapes without exact size. So AMB3R adds a small “scale head” that estimates the true scale. It does this by looking at each frame and predicting the log depth of the pixel that has the median predicted depth, then combines scales from different frames to align everything to real-world sizes.

2) Back-end: “Fusing and reasoning in 3D”

- Voxels: The back-end packs all the predicted 3D points and features into small cubes in space (like 3D pixels called voxels). If multiple pixels from different views point to the same place, they get combined in the same voxel. This is “spatial compactness”—the same spot in 3D should have one consistent description.

- Space-filling curve: It turns the 3D voxel grid into a 1D list (like a snake path that visits every cube) so it can process the data efficiently.

- Transformer: A smart neural network processes this 1D sequence to “reason” about the 3D scene—merging overlapping views, cleaning noise, and making the 3D model more coherent.

- KNN interpolation: Once the back-end improves the voxel features, it passes refined information back to image pixels (like looking up the nearest cubes to a pixel’s 3D point).

- Zero-convolution injection: These improved features are gently wired back into the front-end’s decoder without retraining the whole front-end. This keeps the original model’s strengths while adding better 3D reasoning.

3) Training and extensions

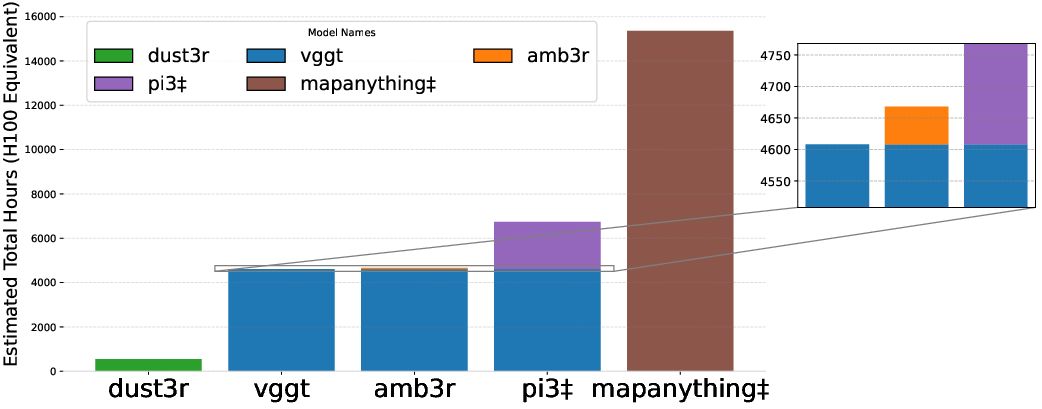

- Training: The front-end is kept frozen (unchanged), and only the back-end and scale head are trained. The authors also align the predicted shapes with standardized training shapes so the model focuses on details instead of fighting scale mismatches. Notably, they trained using academic-level resources (~50–80 H100 GPU hours).

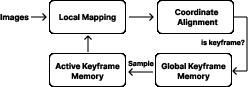

- Visual Odometry (VO)/SLAM: Instead of doing heavy optimization, AMB3R cleverly uses selected “keyframes” as memory. Because pointmaps already use the first frame’s coordinate system, AMB3R can align new predictions to the global scene mostly by estimating scale and fusing results, avoiding complex transformations.

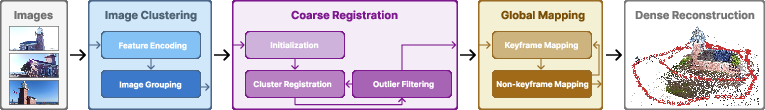

- Structure from Motion (SfM): For large sets of images, AMB3R splits them into small clusters, maps them step-by-step, and then refines globally—again, without slow optimization.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

Here’s what AMB3R achieves across many datasets and tasks:

- Camera Pose Estimation: It outperforms leading feed-forward models on the RealEstate10K benchmark, estimating where the camera was and how it rotated with high accuracy.

- Monocular Depth Estimation (single image): Strong zero-shot performance (no fine-tuning) on common benchmarks like NYUv2 and ETH3D—better than or competitive with models trained specifically for depth.

- Multi-view Depth (multiple images), including metric scale: AMB3R sets new state-of-the-art results across various datasets, even when other methods have access to camera information. Its metric depth is accurate under both strict and practical evaluation settings.

- 3D Reconstruction: It builds detailed 3D models with high accuracy and completeness, matching or beating other feed-forward systems and even some optimization-based ones.

- Video Depth: It handles dynamic videos well, producing stable depth maps across sequences.

- VO/SLAM: AMB3R runs as an online system and, remarkably, can surpass traditional optimization-based methods in some cases—without heavy post-processing.

- SfM: It scales to larger collections of photos using a divide-and-conquer approach while staying feed-forward.

These results matter because they show you can get top-tier 3D quality fast, with practical real-world scale, and without the usual slow, complex optimization steps. That lowers the barrier for many applications.

Implications and Impact

- A unified, fast 3D pipeline: AMB3R brings together depth, camera pose, 3D reconstruction, VO/SLAM, and SfM in one feed-forward system.

- Real-world size awareness: Because it works in metric scale, it’s useful for robotics, AR/VR, mapping, and measurements—where “how big is this?” really matters.

- Efficiency and accessibility: It achieves state-of-the-art results with modest training compute, making advanced 3D modeling more accessible to researchers and developers.

- Robust and general: It handles “in-the-wild” images and varied datasets without task-specific fine-tuning.

- Open-source: The released code, weights, and tools help the community build on this work and push 3D vision forward.

In short, AMB3R shows that smart 3D reasoning in a compact voxel “backend,” combined with a strong “front-end,” can make fast 3D modeling accurate, scalable, and practical—opening the door to many real-world applications where speed and true size matter.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of missing, uncertain, or unexplored aspects in the paper that future researchers could concretely address.

- Backend voxel resolution: The sparse voxel size is fixed at 0.01 in normalized space, without analysis of how voxel size impacts thin structures, fine geometry, or different scene scales. A learned/adaptive voxel resolution and its effect on accuracy and runtime remains unexplored.

- Space-filling curve choice: The paper serializes voxels via space-filling curves but does not ablate or compare different curves (e.g., Hilbert vs. Morton/Z-order) or sequence lengths on locality preservation and transformer effectiveness.

- Transformer backend design: No ablation on the Point Transformer v3 U-Net depth, receptive field, and sequence batching strategy; the contribution of backend depth and attention to final accuracy is unclear.

- KNN interpolation hyperparameters: The choice of k, distance metrics, and weighting in KNN interpolation from voxels to per-pixel features is not specified or analyzed; sensitivity to k and trade-offs between speed and accuracy are unknown.

- Fusion via zero-convolution: The zero-conv injection scheme is adopted without ablation on injection layers, strength, or alternatives (e.g., cross-attention, FiLM), leaving the optimal fusion strategy and its robustness unclear.

- Confidence gating strategy: Backend execution depends on a learned confidence threshold, but threshold calibration, dataset sensitivity, and failure risk (e.g., skipping backend when needed or over-triggering) are not quantified.

- Canonical scale mismatch and ROE alignment: During training, ROE scale alignment is used to mitigate canonical scale inconsistencies, yet numerical stability, failure modes (e.g., degenerate geometry, narrow baselines), and its effect on convergence are not studied.

- Metric scale head robustness: The scale head regresses per-frame log-depth at the median predicted depth pixel; failure under occlusion, dynamic foreground near the median depth, or biased content (e.g., very close-up/macro scenes) is untested.

- Metric scale dependence on priors: The method relies on learned metric cues from frozen VGGT features; how scale estimation generalizes to distributions with unusual object sizes, alien environments (e.g., underwater, endoscopic), or semantic shifts is unknown.

- Dynamic scene handling in reconstruction: The backend enforces spatial compactness and fuses multi-view cues assuming static geometry; there is no explicit motion segmentation or dynamic object modeling, risking ghosting or mis-fusions in dynamic scenes.

- Drift and loop closure in VO/SLAM: The feed-forward VO uses running averages and keyframe resampling without loop closure or global optimization; long-term drift characteristics, loop closure robustness, and large-loop performance are not evaluated.

- Uncalibrated camera intrinsics: The VO/SLAM and SfM claims are “uncalibrated,” but robustness to unknown and varying intrinsics, lens distortion, rolling shutter, and auto-focus changes is not thoroughly evaluated or characterized.

- Large-scale SfM without optimization: The divide-and-conquer SfM avoids BA and global optimization; behavior under repetitive structures, severe viewpoint changes, weak overlaps, and wrong cluster assignments is not analyzed, nor is failure detection/recovery.

- Scalability and resource profiling: The paper lacks runtime, memory, and throughput metrics (per image/sequence) for front-end+backend, including upper bounds on number of frames/images, voxel counts, and sequence lengths; real-time feasibility and scaling to thousands of images remain uncertain.

- Evaluation coverage gaps: No systematic tests on extreme domain shifts (nighttime, specular/transparent surfaces, snow/rain, aerial/drone, satellite, underwater, medical), which are critical for metric scale generalization and 3D consistency.

- Failure case taxonomy: The paper notes metric errors on DTU (toy buildings on white tables with dark backgrounds) but does not provide a systematic analysis of failure patterns, scene attributes causing errors, or mitigation strategies.

- Pose estimation evaluation granularity: Camera pose evaluation uses AUC@30 with 10-sample subsets per scene, without full-sequence or worst-case analyses; sensitivity to trajectory length, baseline distribution, and occlusion is not assessed.

- Robustness to limited parallax: The approach’s behavior under very narrow baselines and small parallax (e.g., handheld jitter) is not measured; stability of pointmap and scale head in near-degenerate configurations is unknown.

- Uncertainty calibration: No quantitative calibration of depth/pose uncertainty or metric scale uncertainty (e.g., predictive intervals, sharpness vs. calibration curves), limiting safe deployment and downstream decision-making.

- Output representation limitations: The backend produces dense points via per-pixel pointmaps; occupancy, TSDF/SDF surfaces, mesh extraction, or radiance fields are not integrated, leaving surface consistency and texture synthesis for downstream tasks unexplored.

- Semantic integration: There is no integration of semantics or object priors to assist metric scale, disambiguate correspondences, or handle dynamic actors; the potential of semantic-driven scale estimation is untested.

- Training data and overfitting risks: The backend trains on a mixture of 12 datasets with 80K samples; there is no dataset ablation, learning curve, or analysis of overfitting/generalization vs. data diversity, nor paper of performance with reduced training budgets.

- Hyperparameter sensitivity in VO/SfM: Multiple VO/SfM thresholds (ηd, ηb, ηmax, Nk_max, Nmin, window sizes) are fixed; sensitivity analyses and automatic tuning strategies for varied domains and motion regimes are missing.

- Coordination of multi-cluster SfM: Cluster-to-cluster alignment relies on local keyframes and ROE-based scaling; accumulation of small misalignments and the conditions where global harmonization (e.g., cycle-consistency or spectral methods) becomes necessary are not explored.

- Comparative analysis with optimization backends: While surpassing some optimization-based methods, the conditions where test-time optimization adds value (e.g., extreme scenes, large loops) and principled hybrid designs that combine feed-forward priors with lightweight optimization remain open.

- Fairness and reproducibility details: Some baselines use different training datasets or are concurrent; comprehensive, uniform evaluation settings (data splits, pre-processing, intrinsics, metrics) and public runtime logs are needed to ensure fair, reproducible comparisons.

- Extension to multi-sensor fusion: IMU, LiDAR, or altimeter cues could stabilize scale and VO; the method’s compatibility and gains from multi-sensor integration are not investigated.

- Handling of radiometric variation: Robustness to exposure changes, HDR, flash/no-flash pairs, severe noise, and motion blur, and potential preprocessing (e.g., photometric normalization) effects on pointmap consistency are not reported.

- Theoretical grounding of “spatial compactness” benefits: The claim that voxel compactness improves correspondence fusion is intuitive but not theoretically analyzed; formalizing when and why compact 3D representations outperform 2D grid-based reasoning would guide design choices.

- End-to-end training vs. frozen front-end: The paper freezes VGGT to preserve confidence functions; whether end-to-end fine-tuning with careful confidence regularization could yield further gains—without catastrophic forgetting—remains unexplored.

Glossary

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN): A type of deep neural network commonly used for analyzing visual images. "The front-end of our architecture employs a Convolutional Neural Network to encode visual features."

Dense 3D Reconstruction: The process of generating a complete 3D model of a scene with detailed spatial information, often from multiple images. "For dense 3D reconstruction, approaches range from traditional methods to modern neural implicit models."

Feed-forward Model: A type of neural network architecture where connections between units do not form cycles, commonly used in deep learning for straightforward processing of input to output. "We present AMB3R, a multi-view feed-forward model for dense 3D reconstruction."

Geometric Reasoning: In computer vision, this refers to the computation and interpretation of shapes and geometries from visual data. "Enabling geometric reasoning with spatial compactness was a key design choice for AMB3R."

K Nearest Neighbor (KNN) Interpolation: A method for predicting values at unobserved locations in space by averaging or considering the nearest known values. "Per-pixel features are obtained via KNN interpolation and injected into the frozen front-end."

Monocular Depth Estimation: The process of estimating depth information from a single image. "AMB3R supports monocular/multi-view metric depth/3D reconstruction."

Multi-view Stereo (MVS): A method in computer vision used for 3D reconstruction, which involves deducing depth information by processing multiple images taken from different angles. "Multi-view stereo methods construct cost volumes for depth estimation."

Pointmaps: A representation of a scene in which pixel locations are mapped to 3D coordinates, often used for camera localization and scene reconstruction. "Pointmaps have emerged as the cornerstone of modern 3D foundation models."

Sparse Voxel Grids: A type of data structure used for representing 3D space in a compact form by only storing non-empty regions of the space. "Thanks to decades of progress in 3D geometry processing, we organize these sparse voxels into a 1D sequence."

Visual Odometry (VO): Techniques in computer vision that estimate camera movement by examining video data. "AMB3R can be seamlessly extended to visual odometry or large-scale structure from motion."

Zero-convolution Layers: A neural network layer that integrates secondary information by adding its features to primary features without altering the core structure. "The fused features are injected back into the front-end decoder via zero-convolution layers."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are concrete, deployable use cases that can be implemented now using the methods, findings, and open-source release described in the paper.

- Sector: Software and Robotics

- Use case: Real-time, uncalibrated visual odometry (VO) for mobile robots and drones without optimization-based backends.

- Tools/workflows: Wrap AMB3R as a ROS2 node that ingests RGB streams, performs keyframe selection and confidence gating, and publishes poses and metric-scale depth; integrate into navigation stacks for indoor robots (e.g., warehouse AGVs) or small UAVs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires sufficient inter-frame overlap and moderate motion; performance degrades with severe dynamics, feature-poor scenes, or extreme lighting; GPU or high-end CPU recommended for low-latency inference; camera intrinsics optional but beneficial.

- Sector: AR/VR and Mobile Software

- Use case: On-device metric-scale scene understanding for AR occlusion, anchoring, and spatial measurements using a smartphone camera (no LiDAR).

- Tools/workflows: Integrate AMB3R into ARCore/ARKit pipelines for depth and pose priors; use AMB3R metric depth to enable tape-measure and room-layout apps; fuse sparse voxels with zero-conv injection for fast updates during AR sessions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires modest compute on mobile; dynamic objects and transparent/specular surfaces are challenging; scale head relies on per-frame visual cues aligned with training distributions.

- Sector: AEC (Architecture, Engineering, Construction)

- Use case: Rapid, feed-forward site documentation and as-built capture from short image sequences (rooms, façades, small outdoor areas).

- Tools/workflows: Replace slow COLMAP-style SfM in photogrammetry workflows with AMB3R to bootstrap 3D point clouds and meshes; export to CAD/BIM via mesh reconstruction pipelines; use confidence gating to decide when to invoke the backend.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Works best on moderate-scale areas seen during training; textureless walls and repetitive patterns may require more viewpoints; metric accuracy sufficient for rough measurements, not for survey-grade without validation.

- Sector: Media, Film, and VFX

- Use case: Fast matchmove and set reconstruction for shot prep and previz using in-the-wild handheld footage.

- Tools/workflows: A plugin that runs AMB3R on selected frames to provide camera trajectory and dense point clouds; export to Blender, Houdini, or Unreal; use the backend only when front-end confidence is low to save compute.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires adequate parallax and overlap; specular/transparent props are hard; may need manual cleanup or a secondary meshing step.

- Sector: E-commerce and Digital Twins

- Use case: Rapid product digitization and indoor inventory mapping from multi-view smartphone captures.

- Tools/workflows: A web service that accepts short image sets, runs AMB3R to produce metric point clouds, and post-processes to meshes for product pages or digital twin catalogs; optionally initialize Gaussian splats/NeRFs with AMB3R’s metric depth.

- Assumptions/dependencies: White backgrounds and high contrast may confuse scale (documented DTU-like failure modes); quality varies with lighting and texture richness.

- Sector: Geospatial and Cultural Heritage

- Use case: Fast documentation of small heritage sites and artifacts without specialized sensors, supporting quick field scans and inspection.

- Tools/workflows: Field app that sequences photos, builds clusters, runs feed-forward SfM with the paper’s divide-and-conquer clustering, and exports an aligned, metric reconstruction; use the open-source evaluation toolkit for QA.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Moderate scene sizes; larger sites require clustering and careful keyframe management; ensure consistent viewpoints and avoidance of large moving crowds.

- Sector: Education and Research (Academia)

- Use case: Baseline for teaching and benchmarking multi-view depth, VO, SLAM, and SfM without expensive training or optimization backends.

- Tools/workflows: Use AMB3R’s open-source code, weights, and evaluation toolkit to create coursework labs; run ablations on confidence gating, keyframe policies, and voxel serialization; generate synthetic labels for training other models.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Results depend on adherence to training distribution; careful selection of datasets improves zero-shot generalization.

- Sector: Public Safety and Policy (Operational)

- Use case: Rapid, on-site scene reconstruction for incident documentation (small crime scenes, minor traffic accidents) using smartphones.

- Tools/workflows: A simple capture app with AMB3R backend to produce metric-scale point clouds and camera paths; export to standardized formats for reports and archival.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Not forensic-grade; sensitive to reflective surfaces and moving subjects; requires clear capture protocol and metadata retention.

- Sector: Video Post-production and Editing

- Use case: Per-frame and multi-frame metric depth for depth-aware effects (relighting, defocus, compositing) and fast scene proxies.

- Tools/workflows: Integrate AMB3R as a plug-in to NLEs/compositors to batch-process clips; use confidence thresholds to route frames to the backend for improved depth on challenging shots.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Results depend on scene motion and texture; unusual cinematography (whip pans, motion blur) may reduce accuracy.

Long-Term Applications

The following require further research, scaling, or development (e.g., domain adaptation, training, hardware optimization, or standards).

- Sector: Large-Scale Mapping and AR Cloud

- Use case: City-scale feed-forward SfM/SLAM for persistent AR cloud maps without global optimization.

- Tools/workflows: Hierarchical clustering, federated keyframe graphs, and confidence-aware blending; distributed mapping on edge devices; server-side reconciliation of submaps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: The current approach mitigates quadratic complexity via clustering, but global consistency over tens of thousands of images likely needs additional loop closures or lightweight optimization; privacy and data governance considerations.

- Sector: Autonomous Driving and Outdoor Robotics

- Use case: Onboard feed-forward metric scene understanding for navigation and obstacle mapping from monocular cameras.

- Tools/workflows: Fuse AMB3R outputs with IMU and wheel odometry; use scale head to stabilize metric estimates; integrate with planners for near-real-time perception.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Training distribution is not vehicle-centric; robust handling of high-speed motion, extreme weather, and repetitive road textures needs domain-specific training and sensor fusion.

- Sector: Healthcare (Medical Endoscopy and Laparoscopy)

- Use case: Feed-forward 3D mapping of internal anatomy for navigation and measurement from monocular endoscope video.

- Tools/workflows: Domain-adapt AMB3R to medical imagery; incorporate motion/lighting priors and non-Lambertian surfaces; validate with phantom datasets; ensure regulatory compliance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Major domain shift; strict accuracy, safety, and explainability requirements; potential need for intrinsics and instrument calibration.

- Sector: Underwater, Space, and Harsh Environments

- Use case: Reconstruction and VO from monocular cameras in low-texture, turbidity, or low-light conditions (ROVs, planetary rovers).

- Tools/workflows: Train on domain-specific data; add physics-informed priors; combine with sonar or stereo when available; robust confidence gating.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Severe distribution shift; sensor noise and environmental artifacts; compute constraints on remote platforms.

- Sector: Collaborative Multi-Robot Mapping

- Use case: Fleet-level feed-forward mapping across robots, sharing keyframes and voxel features to co-build metric maps without heavy optimization.

- Tools/workflows: Shared backend feature stores; keyframe graph synchronization; conflict resolution via ROE-based scale alignment and lightweight pose fusion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Network constraints, clock sync, and data association across agents; eventual need for global consistency checks.

- Sector: High-Fidelity Digital Twins and Survey-Grade Workflows

- Use case: Replace traditional photogrammetry with faster feed-forward pipelines for large assets and facilities while meeting survey standards.

- Tools/workflows: Hybrid pipelines that use AMB3R to initialize and constrain subsequent optimization (bundle adjustment, surface regularization); QA tooling using the paper’s evaluation metrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Survey-grade accuracy likely requires optimization loops, scale validation against ground truth, and metadata standards.

- Sector: Edge Hardware and Efficient Inference

- Use case: Deploy AMB3R on low-power devices (AR glasses, small robots) with real-time constraints.

- Tools/workflows: Model compression, pruning, and quantization; efficient voxel serialization; dynamic backend invocation via confidence thresholds to conserve compute.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Maintaining accuracy under aggressive compression; memory constraints for space-filling curve serialization.

- Sector: Semantics and Scene Understanding

- Use case: Joint geometric-semantic mapping to support reasoning (navigation, manipulation, scene editing).

- Tools/workflows: Extend the voxel backend to store semantic features; couple with panoptic segmentation modules; exploit spatial compactness for multi-view semantic fusion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Additional training on labeled datasets; evaluation measures for accuracy and consistency; handling dynamic entities.

- Sector: Privacy, Standards, and Policy

- Use case: Standardized practices for citizen-science mapping and public-sector incident documentation using feed-forward methods.

- Tools/workflows: Policy frameworks around data collection, retention, and sharing; standardized QA using open-source toolkits; interoperable formats for metric reconstructions and trajectories.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legal compliance (privacy of bystanders, property rights); trust and auditability of feed-forward results; potential certification for official use.

Cross-cutting Assumptions and Dependencies

- Model generalization depends on the training distribution (in-the-wild scenes); domain-specific deployments require finetuning or adaptation.

- Reliable performance requires sufficient viewpoint overlap, textured surfaces, and manageable scene dynamics.

- Metric scale recovery uses per-frame log-depth regression aligned via ROE; extreme frame combinations or atypical capture orders can affect scale stability.

- Confidence gating reduces compute by limiting backend runs; tuning thresholds is workload-dependent.

- The compact voxel backend and serialization/tranformer processing deliver geometric reasoning, but very large-scale scenes still need clustering or hierarchical strategies.

- Open-source availability of code, weights, and evaluation tools accelerates adoption; licensing for VGGT and derivative weights should be confirmed for commercial use.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.