What does it mean to understand language? (2511.19757v1)

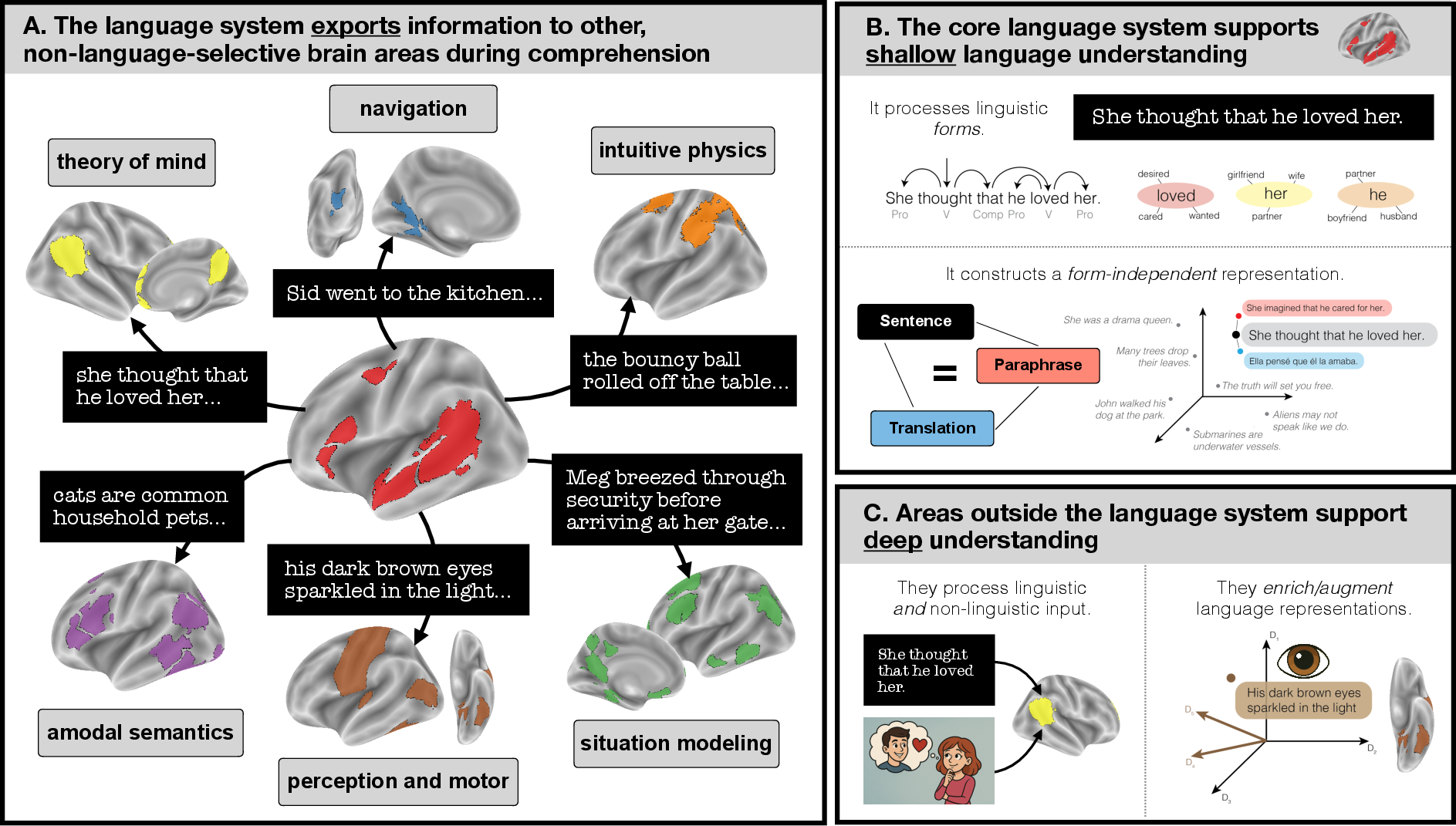

Abstract: Language understanding entails not just extracting the surface-level meaning of the linguistic input, but constructing rich mental models of the situation it describes. Here we propose that because processing within the brain's core language system is fundamentally limited, deeply understanding language requires exporting information from the language system to other brain regions that compute perceptual and motor representations, construct mental models, and store our world knowledge and autobiographical memories. We review the existing evidence for this hypothesis, and argue that recent progress in cognitive neuroscience provides both the conceptual foundation and the methods to directly test it, thus opening up a new strategy to reveal what it means, cognitively and neurally, to understand language.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

A simple explanation of “What does it mean to understand language?”

1) What is this paper about?

This paper asks a big question: when you read or listen to a sentence, what does it really mean to “understand” it? The authors argue that true, deep understanding is more than knowing the words and grammar. It’s building a rich “mental movie” of what’s being described—who’s involved, what they feel, where they are, and what might happen next. They propose that to do this, your brain’s core language areas must “export” information to many other brain systems that handle vision, movement, memory, emotions, social thinking, and more.

2) What are the key questions?

The paper focuses on three main questions, rephrased in everyday terms:

- How much understanding happens inside the brain’s “language hub,” and how much needs help from other parts of the brain?

- When language needs extra help, where does the information go (which brain systems), and what do those systems add?

- Under what conditions does this “exporting” happen, and how might the brain carry it out?

3) How did the researchers paper this?

This is an opinion and review piece. The authors don’t report one new experiment; instead, they connect many past studies to build a new framework.

To do that, they rely a lot on:

- fMRI studies: fMRI is a safe brain scanner that acts like a “heat map,” showing which brain areas use more energy (and blood flow) while you do something, like reading a story.

- Functional localizers: This means first finding each person’s specific brain spots for things like faces (face area), places (place area), or language (language network). That way, researchers can be confident about what each region really does.

- Natural stories and passive reading: They look at brain activity while people just read or listen, without doing extra tasks. This helps show what the brain does during normal understanding, not just when following instructions.

The authors also use simple analogies from AI. They compare the brain’s language system to earlier text-only AI models: good at patterns in words (“shallow understanding”), but needing extra systems (vision, logic, memory) for “deep understanding.”

4) What are the main ideas and why do they matter?

The authors’ core idea is that the brain has a “core language system” that’s amazing at language patterns—recognizing words, grammar, and sentence structure—but that this system alone only supports “shallow understanding.”

- Shallow understanding: Knowing what words go together and forming an abstract meaning based on how language is used. It’s like knowing all the rules of a game but not picturing the game being played.

- Deep understanding: Building a detailed mental model—the characters, setting, causes and effects, time, emotions, and how it connects to your life.

They argue you get deep understanding only when the language system “exports” information to other brain systems. Think of it like this: your language hub is a great translator, but to really understand, it has to share the translated message with other “departments” in your brain.

Here are some of those “departments” and when they get involved:

- Thinking about people’s thoughts (“theory of mind” areas): Used when a story describes what someone believes, intends, or feels.

- Intuitive physics network: Used when you reason about physical situations (e.g., whether something can fall, break, or balance).

- Navigation and scene areas (place-related regions like PPA, OPA, RSC): Used for understanding places, routes, or room layouts in text.

- Perception and motor areas (vision/movement systems): Can get involved when text is vivid (faces, bodies, motion) or describes actions you can simulate (e.g., “kick,” “grasp”).

- Emotion-related regions: Activated by emotionally charged passages (fear, joy, sadness).

- Memory systems:

- Episodic memory: Personal memories (e.g., recalling your own similar experience while reading).

- Semantic memory: General knowledge about the world (facts and concepts).

- “Default network”: A set of areas that help integrate information over longer stretches (like chapters of a story). These may help knit everything into a coherent “situation model” across time.

Why this matters:

- It explains why reading a story can feel like “being there.” Your brain isn’t just parsing sentences—it’s calling in specialists to build the scene, simulate actions, predict outcomes, and connect to your memories.

- It sets a clear plan for future research: scientists can test, with fMRI and careful methods, exactly which “extra” brain areas get involved during normal reading, and when.

How do we know when exportation is happening? The authors suggest strong evidence should:

- Come from brain regions with clear, specific functions (e.g., the face area for faces).

- Identify those regions in each person individually (not just average across people).

- Use passive reading/listening (no special tasks), so findings reflect natural understanding.

When is exportation more likely?

- Longer or more complex text (the language system has a short memory and needs help keeping track over time).

- When the topic is personally relevant or interesting (you bring in more memories, imagery, and emotion).

- When the sentence is clear enough that the language system can create a good, shareable representation.

How might exportation work?

- Routing: like sending a message to the most relevant “department.”

- Broadcasting: like posting in a group chat and letting relevant “departments” pick it up. The authors think both directions of information flow matter: language informs other systems during comprehension, and other systems send information back when we speak or when context/vision/gestures influence understanding.

5) What could this change or inspire?

- For brain science: It gives a concrete roadmap for experiments to test deep language understanding—what regions are involved, how they coordinate, and under what conditions.

- For AI: It suggests that LLMs become more “deeply understanding” when they connect to other systems (vision, reasoning, memory), not just more text. That mirrors how the human brain likely works.

- For education: It highlights that true understanding involves building rich mental models, not just repeating words. This could guide better ways to check if students really “get it.”

- For future research: It lists open questions, like whether exportation is routine or occasional, how the brain translates language into formats other systems use, and whether messages are routed or broadcast.

In short, the paper reframes language understanding as a team effort. The language system gets the words right, but deep understanding happens when many brain systems work together to turn those words into a living, breathing story in your mind.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, concrete list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored, framed to enable actionable follow‑up studies.

- Lack of direct, causally validated evidence for exportation during passive comprehension across most proposed extra‑linguistic target systems; design experiments with within‑subject functional localizers, naturalistic text, and content time‑locking to test engagement without explicit tasks.

- Unspecified “translation layer” by which language‑system representations interface with downstream systems; identify and characterize the intermediate code (e.g., via representational similarity analysis and cross‑modal decoding) and determine whether it is continuous/distributional or symbolic/propositional.

- No agreed behavioral operationalization of “deep understanding”; develop validated, task‑free behavioral metrics that track situation‑model richness (e.g., memory for causal/spatial relations, inference consistency, counterfactual integration) and align them with neural measures.

- Incomplete mapping of perceptual exportation: unknown whether ventral visual category‑selective areas (FFA, PPA/OPA/RSC, MT) are engaged by passive reading of vivid descriptions; test with individualized localizers, content‑controlled narratives, and time‑locked analyses.

- Motor embodiment evidence remains methodologically mixed; determine necessity vs. epiphenomenality using high‑resolution intracranial recordings, perturbation (TMS/TES) and lesion studies while controlling for phonological and imagery confounds.

- Emotional processing lacks functionally selective markers and suffers from reverse‑inference ambiguity; apply multivariate decoding and searchlight analyses to dissociate emotion‑related engagement during passive comprehension from ToM and DN‑A activity, avoiding explicit emotion judgments.

- The role and format of amodal semantic memory systems in passive language understanding is unresolved; localize candidate semantic hubs within individuals and test their time‑locked engagement and representational content during naturalistic comprehension.

- Situation‑model construction locus is ambiguous (single DN vs. dynamic coordination among domain‑specific systems, potentially hippocampal‑dependent); reanalyze prior DN findings using individualized ToM vs. DN‑A parcellations and test hippocampal contributions to cross‑domain binding and temporal integration.

- Temporal dynamics of exportation are unknown; use MEG/ECoG/fast fMRI to measure latency and directionality of information flow from language areas to destination networks and back during comprehension.

- Mechanism of information transfer (selective routing vs. broad broadcasting) is untested; apply effective connectivity (e.g., dynamic causal modeling), closed‑loop stimulation, and model‑based perturbations to adjudicate these hypotheses.

- Quantitative prevalence of exportation in everyday comprehension is unmeasured; build corpora with annotated content dimensions and quantify exportation rates across genres, input lengths, and contexts under passive conditions.

- Determinants of exportation (stimulus complexity, context length, language proficiency, prior knowledge, interest, alertness, imagery ability) lack parametric characterization; conduct factorial designs to model how these variables modulate destination recruitment and comprehension outcomes.

- Bidirectional interactions are underspecified; test how extra‑linguistic signals (visual context, gesture, common ground) modulate processing in the core language system during comprehension, including predictive and error‑signal effects.

- Plausibility constraints appear absent in the core language system; localize where plausibility is computed (e.g., DN‑A, ToM, semantic hubs) and determine how and when those computations feed back to language areas.

- Cross‑linguistic generality of exportation is unknown; replicate destination‑engagement effects in typologically diverse languages and in bilinguals, controlling for proficiency, orthography, and structural differences.

- Developmental trajectory of exportation is unexplored; investigate when and how children begin to export to specific systems and how literacy, world knowledge, and schooling shape these pathways.

- Clinical relevance is untested; characterize exportation deficits in aphasia, autism/ToM impairments, hippocampal damage, and MD‑system dysfunction, and quantify their impact on deep comprehension to validate necessity of destination systems.

- Conflicting reports of no exportation lack synthesis; identify task, stimulus, and analysis features (e.g., group averaging, lack of individual localizers) that suppress destination engagement to specify boundary conditions.

- Representation format in destinations (e.g., variable binding, causal relations, spatial maps) remains uncharacterized; develop decoding tasks and formal computational models to read out specific relational structure during comprehension.

- Capacity limits of the language system and handoff thresholds are not quantified; determine the context length at which exportation becomes necessary and how buffer size varies across individuals and states (fatigue, alertness).

- AI alignment of exportation is incomplete; define and measure “exportation signatures” in multimodal/modular AI systems, test whether they improve prediction of human neural dynamics beyond text‑only LLMs, and assess causal importance of emergent specialized units.

- Methodological standards are uneven; adopt individual functional localization, naturalistic stimuli with content annotations, preregistered analyses, multivariate models, and report negative results to strengthen inference about exportation.

Glossary

- Amygdala: A subcortical brain structure central to processing emotional valence and arousal. "the emotional valence of the words in short passages from Harry Potter modulated responses in the amygdala."

- Amodal semantic processing: Processing of meaning that is independent of input modality (e.g., language or vision). "amodal semantic processing [23]"

- Anterior cingulate cortex: A medial frontal brain region implicated in diverse cognitive processes including conflict monitoring and error detection. "whereas engagement of anterior cingulate cortex would be consistent with numerous disparate cognitive processes."

- Auditory cortex: Cortical regions specialized for processing auditory information such as speech and music. "regions of auditory cortex selective for the perception of speech sounds and music [14-15]"

- Autobiographical memories: Personal episodic memories about events from one’s own life. "our world knowledge and autobiographical memories."

- Broadcasting: A hypothesized export mechanism where language representations are sent broadly to many downstream systems. "A different possibility is that representations constructed by our language system are sent to all possible downstream systems all the time (i.e., “broadcasting”)."

- Compositional representation: A structured meaning representation built by combining parts (words, constructions) according to syntax/semantics. "constructing a compositional representation of the sentence’s meaning"

- Core language system: A network of frontal and temporal regions specialized for processing and producing language. "The core language system, however, is selective for language only."

- Default Network (DN): A large-scale brain network involved in integrating information over extended contexts and internally directed cognition. "Some studies have implicated the “default network” (DN) [95-96]."

- Default Network A (DN-A): A subnetwork associated with episodic projection and possibly spatial representation/navigation. "Episodic memory represents personal memories of past events and has been linked to a distributed network of regions in the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes (“Default Network A”, DN-A [24,17]; see [89] for a review)."

- Distributional framework: A representational approach where meanings are captured by statistical co-occurrence patterns across contexts. "all of our ideas are compatible with a distributional framework [58]."

- Embodied cognition: The view that understanding language involves engaging perceptual and motor systems. "Although the general idea behind embodied cognition [53-54,81] aligns with the view we propose here..."

- Episodic memory: Memory for personally experienced events, tied to specific times and places. "Episodic memory represents personal memories of past events..."

- Episodic projection: The ability to remember the past and imagine the future by projecting oneself in time. "the DN-A was originally implicated in episodic projection (remembering the past and imagining the future [118])"

- Episodic retrieval: The process of recalling personal past events from memory. "episodic retrieval and self-projection [24,17]"

- Exportation: Transferring information from the language system to other brain regions for deeper processing. "we argue that exportation can also happen when language simply provides a description during passive reading or when listening to a story."

- fMRI: Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging; a neuroimaging method that measures brain activity via blood-oxygen-level changes. "fMRI research over the last 15 years has identified and characterized the brain's core language system with new precision (see [10] for review)."

- Fusiform Face Area (FFA): A ventral visual region specialized for face perception. "engagement of the FFA during language understanding would provide strong evidence that a face percept has been constructed"

- Hippocampal-dependent: Requiring the hippocampus, typically for memory integration or binding over time. "possibly hippocampal-dependent [105-107]"

- Intuitive physical reasoning: Rapid, automatic reasoning about the physical world and object interactions. "Growing evidence implicates regions of the parietal and frontal cortex in this intuitive physical reasoning (aka the “Physics Network” [21,67])."

- Intracranial study: Neural recording directly from the brain, typically via electrodes placed on or in cortical tissue. "a more recent intracranial study found cross-decoding of neural responses from action words to videos depicting those actions [80]"

- Localizer task: A functional MRI task used to identify specific brain regions in individual participants. "with a standard ‘localizer’ task."

- Medial Place Area (MPA): An area within retrosplenial cortex linked to scene representation and navigation. "retrosplenial cortex (RSC, or “medial place area”, MPA [12,71])."

- Multiple-Demand system: A domain-general network engaged by cognitively demanding tasks across modalities. "as the domain-general processing characteristic of the ‘Multiple-Demand’ system [25]"

- Occipital Place Area (OPA): A visual region selective for scene boundaries and navigationally relevant features. "the occipital place area (OPA, [70])"

- Parahippocampal Place Area (PPA): A ventral visual region specialized for scene and place perception. "including the parahippocampal place area (PPA, [12])"

- Probabilistic programing engines: Computational systems that represent and reason using probabilistic programs. "translate them into a format compatible with probabilistic programing engines [55-56]"

- Resting state: Brain activity measured in the absence of explicit task demands, used to infer functional connectivity. "functional correlations derived from resting state (e.g., [138])"

- Retrosplenial Cortex (RSC): A cortical region involved in scene processing and navigation. "retrosplenial cortex (RSC, or “medial place area”, MPA [12,71])."

- Reverse inference: Inferring cognitive processes from activation in particular brain regions. "Inferences of the engagement of specific mental processes from activation in particular anatomical locations (or “reverse inference” [137])"

- Right temporo-parietal junction (rTPJ): A region selectively engaged in representing others’ mental states. "the right temporo-parietal junction (rTPJ), which is selectively engaged in thinking about what others are thinking [16]"

- Routing: A hypothesized export mechanism where information is selectively directed to the most appropriate downstream system. "One possibility is that the language system preferentially sends information to the most likely target destination (i.e., “routing”)."

- Semantic memory: General world knowledge not tied to specific episodes, including concepts and facts. "Semantic memory instead consists of our general conceptual knowledge of objects, people, places, and facts about the world [90-92]."

- Self-projection: Mentally placing oneself into past or future scenarios or other perspectives. "episodic retrieval and self-projection [24,17]"

- Situation models: Integrated mental representations of the events, entities, goals, and relations described by language. "we construct situation models (see Glossary) when processing language..."

- Symbolic problem solvers: Systems that perform reasoning using discrete symbolic representations and rules. "translate them into a format compatible with probabilistic programing engines [55-56] or symbolic problem solvers [57]"

- Theory of mind (ToM): The capacity to represent and infer others’ beliefs, desires, and intentions. "theory of mind (ToM), the ability to construct a mental model of someone else’s mind."

- ToM network: The network of regions (including rTPJ) specialized for representing others’ mental states. "that together constitute the ToM network [16-18]."

- Ventral visual pathway: A pathway in the visual system specialized for high-level object and category perception. "regions in the ventral visual pathway selectively engaged in perception of faces, bodies, and scenes [11-13]"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following use cases leverage the paper’s exportation hypothesis, methodological desiderata, and domain-specific brain systems to deliver practical value today.

- AI assistant routing to specialized tools

- Sectors: software/AI, robotics, navigation

- Use case: Improve task performance by “exporting” queries from an LLM to dedicated engines (e.g., physics simulators for physical reasoning, map APIs for spatial/navigation queries, knowledge bases for semantic recall, social-reasoning modules for ToM).

- Tools/products/workflows: LLM orchestration frameworks with tool routers; skill libraries (simulation, search, logic); unit tests that require ToM, spatial, and physical inference; telemetry for routing decisions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality tool integrations; latency tolerances; reliable detection of content features (e.g., “this input needs spatial reasoning”); clear evaluation criteria for success.

- Benchmarking “deep understanding” behaviors in AI

- Sectors: software/AI, academia

- Use case: Evaluate models on tasks that mirror exportation destinations (ToM, intuitive physics, scene/navigation, episodic/semantic memory, perception/motor imagery) under passive comprehension and minimal instruction.

- Tools/products/workflows: A benchmark suite combining annotated narratives, grounded simulations, and multi-modal probes; scoring protocols distinguishing shallow vs deep responses; analysis dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Curated datasets with validated ground truth; consensus on task design (e.g., passive comprehension vs explicit tasks); fairness and cultural validity.

- Research pipelines that use individual functional localizers

- Sectors: academia (cognitive neuroscience)

- Use case: Improve interpretability and replicability of language studies by functionally identifying regions (e.g., PPA, OPA, FFA, rTPJ) within each participant and using passive comprehension paradigms.

- Tools/products/workflows: Open-source localizer task library; pre-registered analysis specs; participant-level ROI extraction; story stimuli annotated by content dimensions (ToM, spatial, physical).

- Assumptions/dependencies: MRI/iEEG access; IRB approvals; analyst training; adequate sample sizes.

- Education: teaching situation-model building for reading comprehension

- Sectors: education

- Use case: Shift curricula and assessments from surface parsing to construction of situation models (characters, goals, spatial layout, temporal/causal links).

- Tools/products/workflows: Lesson plans prompting perceptual/motor imagery, ToM inference, spatial mapping; rubrics distinguishing literal recall from model-based understanding; formative assessments aligned to exportation targets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Teacher training; alignment with standards; age-appropriate materials; consideration of neurodiversity and language proficiency.

- Healthcare communication that reliably engages extra-linguistic systems

- Sectors: healthcare

- Use case: Improve patient understanding by crafting materials that cue spatial layouts (e.g., care pathways), ToM (perspective-taking), timelines/causal chains, and vivid perceptual details.

- Tools/products/workflows: Template-based patient education sheets; narrative framing for instructions; visuals aligned with text to support scene and motor representations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Health literacy; cultural tailoring; regulatory review (plain language requirements); clinician training.

- Clinical neuropsychological assessment distinguishing language vs extra-linguistic deficits

- Sectors: healthcare/clinical psychology

- Use case: Differentiate impairments in core language parsing from deficits in ToM, episodic memory, spatial navigation, or physical reasoning during comprehension.

- Tools/products/workflows: Test batteries with matched linguistic complexity but varying content (mental states, spatial layouts, physical processes); normative data and scoring guidelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Validated instruments; training for interpretation; accounting for comorbidities and attention/alertness.

- UX and safety documentation that leverages motor and perceptual imagery

- Sectors: manufacturing, aviation, energy

- Use case: Reduce procedural errors by using stepwise narratives that cue motor imagery and perceptual features (e.g., “feel resistance,” “align with the slot,” “doorway orientation”).

- Tools/products/workflows: Instruction design standards; scenario-based diagrams; user testing focusing on comprehension depth.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear language; multilingual support; compliance and safety review; user diversity.

- Media and learning content annotation with content features

- Sectors: media, edtech

- Use case: Use LLMs and human review to tag narratives for ToM, spatial, physical, emotional, episodic/semantic features to optimize engagement and comprehension.

- Tools/products/workflows: Annotation pipelines; editorial dashboards; A/B testing on comprehension outcomes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quality control on annotations; privacy/consent; cross-cultural generalization.

Long-Term Applications

These use cases require further empirical validation, multi-modal measurement, or advances in AI architecture and neurotechnology.

- Neuroadaptive reading platforms that gauge comprehension depth

- Sectors: education, edtech

- Use case: Adapt text pacing, visuals, and prompts in real time based on neural/behavioral biomarkers of exportation (e.g., engagement of ToM or spatial systems).

- Tools/products/workflows: Wearable EEG/fNIRS/eye-tracking; model-driven adaptation policies; privacy-preserving analytics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable, scalable biomarkers of deep understanding; regulatory approvals; data protection.

- Clinical biomarkers for prognosis and therapy targeting exportation pathways

- Sectors: healthcare

- Use case: Use exportation signatures (e.g., rTPJ engagement during ToM comprehension, PPA/RSC during spatial text) to predict recovery in aphasia, autism, TBI, or aging-related decline.

- Tools/products/workflows: fMRI/MEG/iEEG protocols; longitudinal datasets; targeted rehabilitation programs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Large, diverse cohorts; causal validation; cost-effectiveness and access equity.

- Brain stimulation adjuncts to language therapy

- Sectors: healthcare

- Use case: Augment language rehabilitation by modulating extra-linguistic systems (e.g., TMS/tDCS to ToM or DN-A regions) during narrative comprehension tasks.

- Tools/products/workflows: Combined behavioral-stimulation protocols; safety monitoring; personalized targeting using functional localizers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: RCTs demonstrating efficacy; safety and ethical oversight; precise targeting capabilities.

- Standards and policy for “depth of understanding” in AI systems

- Sectors: policy, software/AI

- Use case: Governance frameworks that require disclosure of shallow vs deep comprehension capabilities and audit of tool-routing decisions for high-stakes applications.

- Tools/products/workflows: Certification criteria; transparency reports; independent audits tied to deep-understanding benchmarks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Consensus definitions; regulatory capacity; industry adoption.

- Exportation-aware neuro-symbolic AI architectures

- Sectors: software/AI, robotics

- Use case: Design architectures that implement routing/broadcasting from a language core to specialized modules (vision, physics, ToM, memory), with learned interfaces and causal specialization.

- Tools/products/workflows: Modular training pipelines; interface languages (probabilistic programs, symbolic schemas); causal probing tools to verify specialization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Scalable training data; compute resources; robust evaluation linking modules to outcomes; avoidance of brittle heuristics.

- Personalized AI with autobiographical memory integration

- Sectors: software/AI, productivity

- Use case: Enhance assistant comprehension by integrating user-specific episodic and semantic stores to construct richer situation models and reduce working-memory bottlenecks.

- Tools/products/workflows: Secure personal memory stores; retrieval-augmented generation; consent and data governance workflows.

- Assumptions/dependencies: User trust; privacy-preserving design; memory accuracy and calibration; legal compliance.

- Neuro-informed instructional design in high-stakes environments

- Sectors: aviation, defense, energy, healthcare

- Use case: Create training and SOPs that explicitly engage spatial/navigation, motor, and ToM systems to improve decision-making under stress.

- Tools/products/workflows: Scenario simulations; multi-modal storytelling; performance analytics tied to comprehension depth.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain validation; ethical considerations; transfer to real-world performance.

- Journalism and public communication optimized for situation-model formation

- Sectors: media, public policy

- Use case: Craft public advisories (e.g., emergency instructions) that trigger spatial, causal, and ToM processing to increase adherence and reduce misunderstanding.

- Tools/products/workflows: Content frameworks; field experiments measuring behavior change; accessibility standards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cultural sensitivity; readability; collaboration with behavioral scientists.

- Lifespan interventions to maintain exportation capacity

- Sectors: healthcare, public health

- Use case: Prevent cognitive decline affecting deep language understanding through programs that train perceptual imagery, spatial mapping, ToM, and episodic recall via guided reading.

- Tools/products/workflows: Digital therapeutics; personalized training schedules; outcome tracking.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Longitudinal efficacy evidence; adherence; integration with clinical care.

- Real-time comprehension monitoring for error reduction

- Sectors: operations, safety-critical industries

- Use case: Detect shallow comprehension states (e.g., working-memory overload in core language network without downstream exportation) to trigger support or confirm-read steps.

- Tools/products/workflows: Behavioral proxies (response latency, paraphrase generalization), physiological signals; human-in-the-loop safeguards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable detection with low false positives; privacy and ethics; worker acceptance.

Cross-cutting assumptions and dependencies

- Measurement: Valid, ethically deployable biomarkers and task designs that distinguish shallow vs deep understanding (especially under passive comprehension).

- Generalization: Cultural, linguistic, and neurodiversity considerations in content and assessment.

- Tooling: High-quality specialized modules (physics, vision, ToM, memory) and robust orchestration for AI applications.

- Ethics and privacy: Strong governance for neurodata and personal memory integration; transparency for AI capabilities.

- Evidence base: Continued empirical work to test exportation across domains, refine situation-model measures, and establish causal links to outcomes.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.