First measurement of reactor neutrino oscillations at JUNO (2511.14593v1)

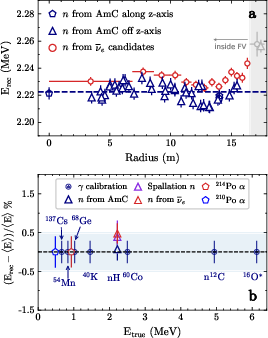

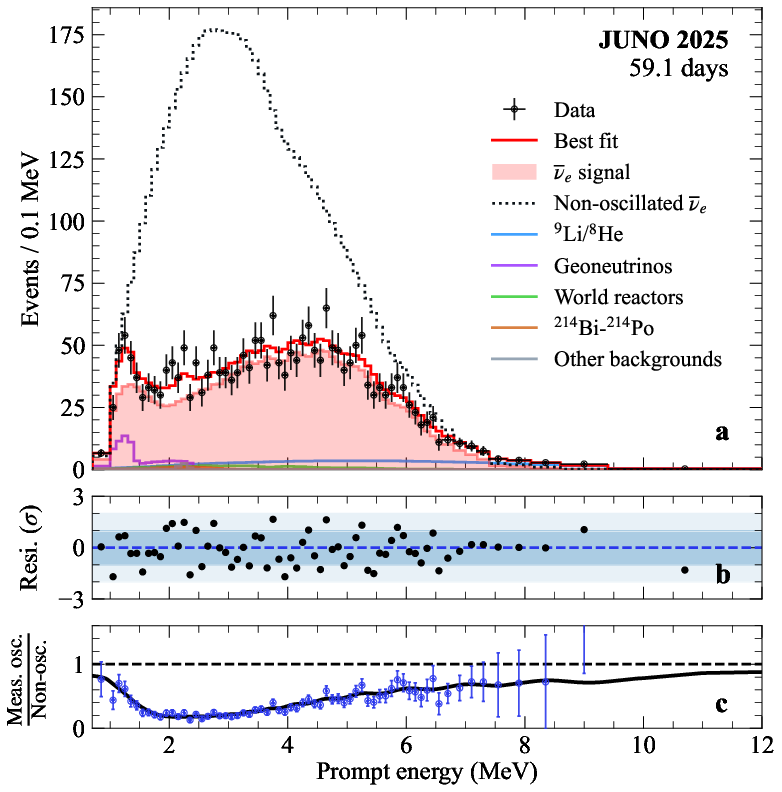

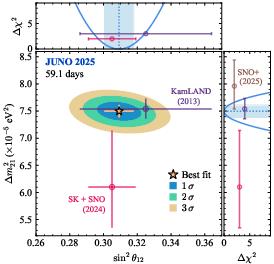

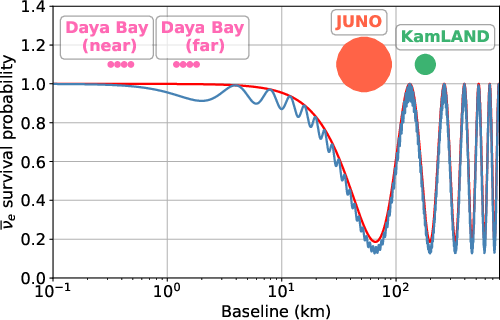

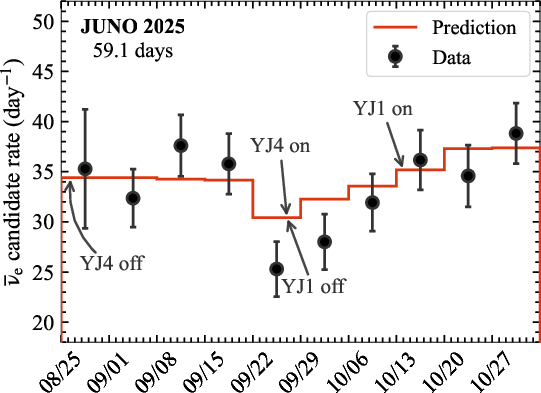

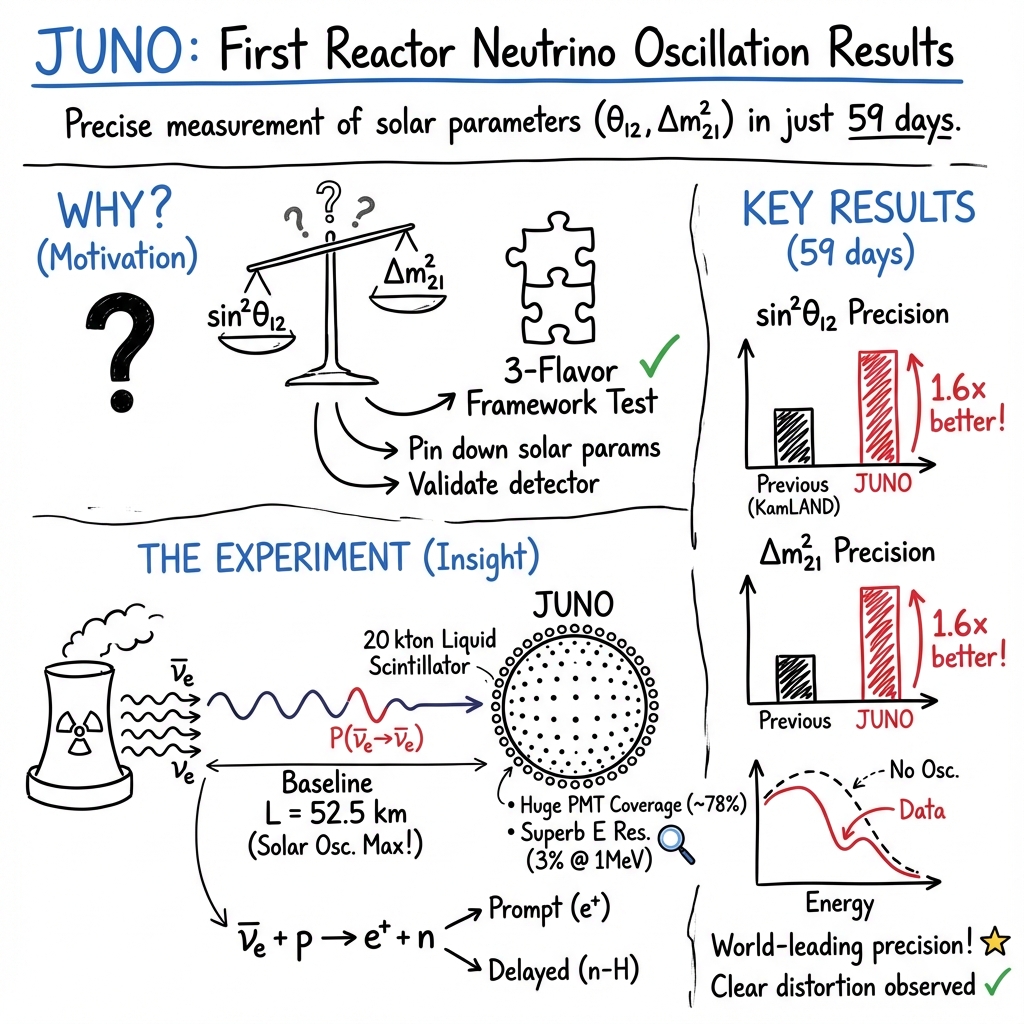

Abstract: Neutrino oscillations, a quantum effect manifesting at macroscopic scales, are governed by lepton flavor mixing angles and neutrino mass-squared differences that are fundamental parameters of particle physics, representing phenomena beyond the Standard Model. Precision measurements of these parameters are essential for testing the completeness of the three-flavor framework, determining the mass ordering of neutrinos, and probing possible new physics. The Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO) is a 20 kton liquid-scintillator detector located 52.5 km from multiple reactor cores, designed to resolve the interference pattern of reactor neutrinos with sub-percent precision. Here we report, using the first 59.1 days of data collected since detector completion in August 2025, the first simultaneous high-precision determination of two neutrino oscillation parameters, $\sin2 θ{12} = 0.3092\,\pm\,0.0087$ and $Δm2{21} = (7.50\,\pm\,0.12)\times10{-5}\;{\rm eV}2$ for the normal mass ordering scenario, improving the precision by a factor of 1.6 relative to the combination of all previous measurements. These results advance the basic understanding of neutrinos, validate the detector's design, and confirm JUNO's readiness for its primary goal of resolving the neutrino mass ordering with a larger dataset. The rapid achievement with a short exposure highlights JUNO's potential to push the frontiers of precision neutrino physics and paves the way for its broad scientific program.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

First measurement of reactor neutrino oscillations at JUNO — explained simply

What is this paper about?

This paper announces the first big physics results from JUNO, a giant underground detector in China that studies neutrinos—tiny, almost invisible particles that fly through everything. JUNO used neutrinos coming from nearby nuclear power plants to measure how neutrinos “change type” as they travel. This change is called neutrino oscillation.

What questions were the scientists trying to answer?

The team wanted to measure two key numbers that describe how neutrinos switch between types (also called “flavors”):

- How strongly two of the neutrino types mix with each other. This is described by a “mixing angle” written as .

- How different the masses of two neutrino types are. This is described by a “mass-squared difference” written as .

Measuring these precisely helps test our current theory of neutrinos and prepares JUNO to answer a huge question next: which neutrino is the heaviest and which is the lightest (this is called the “neutrino mass ordering”)?

How did they do it? (In everyday language)

Think of neutrinos like chameleons that change color (their “flavor”) as they move. How fast and how much they change depends on those two key numbers. JUNO measures these numbers by watching how many neutrinos arrive with different energies.

Here’s the basic idea of the experiment:

- Neutrino source: Nuclear reactors produce a flood of antineutrinos. JUNO sits about 52.5 km away—just the right distance to see a clear pattern in how they change.

- Big, super-sensitive detector: JUNO is a huge clear sphere filled with 20,000 tons of special liquid that flashes when a neutrino interacts. It’s surrounded by thousands of light sensors (like ultra-sensitive cameras) to catch these tiny flashes.

- Underground location: The detector sits deep under a hill to block most cosmic rays from space, which would otherwise create “fake” signals.

- How neutrinos are seen: An antineutrino can hit a proton in the liquid and produce two signals: 1) a “prompt” flash from a positron (like an anti-electron), 2) a “delayed” flash a tiny fraction of a second later when a neutron is captured. Seeing this two-part flash is like a fingerprint that tells researchers, “That was an antineutrino!”

- Reading the energy “ripples”: If you plot how many neutrinos arrive at each energy, oscillations create a wavy pattern—like ripples on a pond. The shape of these ripples lets JUNO calculate the mixing angle and mass difference very precisely.

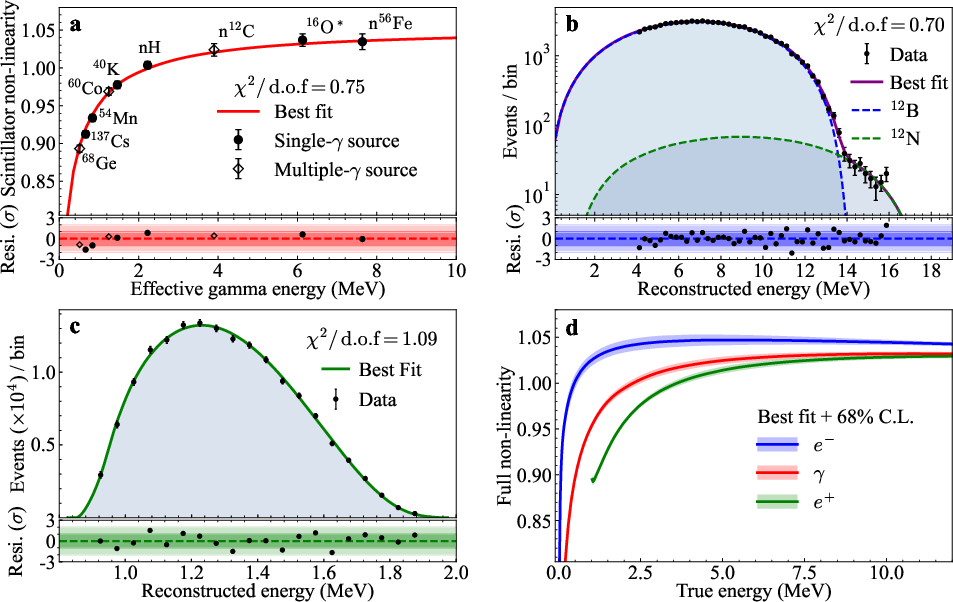

- Careful calibration: The team checked their “energy scale” (how bright a flash equals how much energy) using small radioactive sources and natural signals, making sure their “ruler” is accurate to about half a percent. This is like regularly checking a scale with standard weights so you trust every measurement.

What did they find?

Using just 59.1 days of high-quality data (a short time for such a big experiment), JUNO measured:

Why this is impressive:

- These are two of the most important numbers in neutrino physics.

- JUNO improved the precision (the “sharpness” of the measurement) by about 1.6 times compared to all previous world data combined.

- Doing this so quickly shows that the detector works as designed and is ready for even tougher goals, like figuring out the neutrino mass ordering.

Why does this matter?

- Tests our best theory: Precise measurements let scientists check whether our current three-neutrino model is complete, or whether there are hints of new physics.

- Prepares for the big question: With more data, JUNO aims to determine the neutrino mass ordering—who’s heaviest and who’s lightest—a major missing piece in particle physics.

- Helps other research: Better neutrino knowledge affects studies of supernovae, the early universe, and even the structure of matter.

What’s the bigger picture?

This first result is like a “proof of power” for JUNO. It shows the experiment can deliver extremely accurate measurements in a short time. As JUNO collects more data, it can:

- Pin down the mass ordering of neutrinos.

- Test whether the standard three-flavor picture truly holds up.

- Search for hints of new physics beyond our current understanding.

- Catch neutrinos from supernova explosions and paper neutrinos coming from inside the Earth.

In simple terms: JUNO has turned on, worked beautifully, and already sharpened our picture of how neutrinos behave. It’s on track to answer even bigger questions about the universe.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise, actionable list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper’s first JUNO oscillation analysis, focusing on topics that would enable targeted follow-up work.

- Neutrino mass ordering (NMO) not yet addressed: explicit projection of exposure, background, and energy-scale requirements to achieve a given NMO significance (e.g., 3–5σ) is not provided for the current detector performance.

- External-parameter dependence: the fit strategy’s treatment of and (priors vs. free parameters) and their impact on the and uncertainties are not quantified.

- Reactor antineutrino spectrum modeling: the reference flux/spectrum model(s) used (e.g., Huber–Mueller, ab initio, or data-driven) and the associated covariance are not described; it remains unclear how model uncertainties propagate to the oscillation parameters.

- 5 MeV “bump” treatment: no explicit discussion of whether a spectral anomaly around 4–6 MeV is present in this dataset, how it is modeled, or its potential bias on extraction.

- Core-by-core reactor modeling: the handling of non-identical baselines and time-varying core powers (outages, ramps) and their contribution to spectral smearing and systematics is not documented.

- Spent fuel and off-equilibrium isotopes: contributions from spent fuel pools and long-lived fission products and their uncertainties are not quantified in the flux prediction.

- Geoneutrino background: modeling, subtraction strategy, and uncertainty of U/Th geoneutrinos in the 1–3.5 MeV region—and their impact on —are not presented.

- IBD detection efficiency: the absolute efficiency and its error budget (prompt/delayed energy windows, time/space coincidence, multiplicity vetoes, neutron capture fraction on H vs C, electronics/live-time effects) are not given.

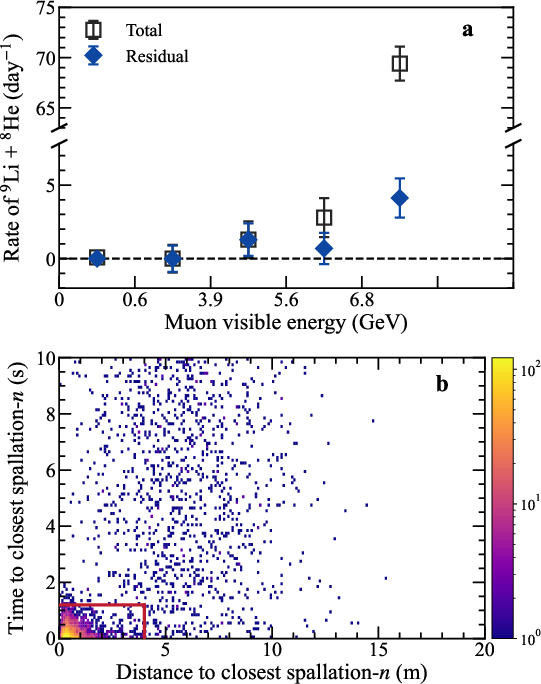

- Cosmogenic backgrounds: rates, spectra, and residual uncertainties for Li/He, fast neutrons, and other muon-induced backgrounds; muon-tagging efficiency, tracking performance, and veto-induced deadtime are not detailed.

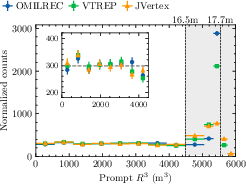

- Fiducial volume (FV) definition: the FV selection, its stability, and the associated fractional uncertainty on rate and spectral shape are not reported.

- Energy resolution performance: quantitative, position- and time-dependent resolution versus the 3% at 1 MeV target is not shown, nor is the contribution of resolution modeling to the oscillation-parameter errors.

- Energy-scale non-linearity coverage: constraints are reported from sources up to ~6 MeV, but a positron-like calibration across the full IBD range (1–8 MeV) is not demonstrated; impact of e vs response differences on is not quantified.

- Absolute energy-scale uncertainty: the current 0.5% scale uncertainty is reported but not decomposed; a roadmap to reach <0.3% (typically needed for robust NMO sensitivity) is not laid out.

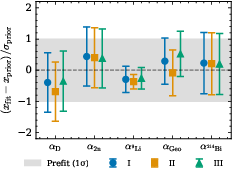

- Response-model degeneracies: correlations between energy-scale/non-linearity parameters and oscillation parameters (pull terms, covariance matrices) are not provided for external scrutiny.

- Dual-PMT system cross-calibration: residual differences between 20-inch and 3-inch PMT systems (charge linearity, timing, pileup, afterpulsing) and their propagation to the energy response are not quantified.

- Reconstruction algorithm systematics: while multiple algorithms yield “comparable” performance, a quantitative comparison and the associated systematic envelope are not shown.

- Matter effects: the treatment of Earth-matter corrections along 52.5 km and the uncertainty from crustal density models on the extracted parameters are not discussed.

- Baseline and geometry uncertainties: errors on reactor core positions, detector center definition, and baseline distances—and their contribution to the uncertainty—are not reported.

- IBD cross-section systematics: inclusion of radiative corrections, recoil, weak magnetism, and their uncertainties in the fit is not specified.

- Time-stability of the detector: beyond the reported 0.2% temporal variation, long-term stability of LS optical properties (attenuation, light yield, quenching), PMT gains, and their control over year-scale exposures are not assessed.

- Boundary and gamma-leakage effects: validation of neutron-capture (2.223 MeV) energy reconstruction near the FV boundary and residual biases from gamma escape are not quantified.

- Reactor-operations robustness checks: week-by-week or configuration-split fits to test stability against changing reactor conditions are not reported.

- Consistency with solar data: a quantitative compatibility test with solar-neutrino determinations (e.g., global-fit pull, possible hints of non-standard interactions) is not provided.

- Data products for external validation: unfolded prompt-energy spectrum, detector response matrices, and background templates are not released to enable independent cross-checks.

- Broader BSM reach in early data: constraints on sterile neutrinos, non-standard interactions, or CPT-violating effects with this dataset are not explored.

- Path to measuring with JUNO-only data: the analysis strategy, exposure, and systematic thresholds needed to extract atmospheric-scale parameters (and their synergy with NMO extraction) are not quantified.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following items translate JUNO’s reported methods, instrumentation, and early physics results into deployable uses across sectors. Each item includes sector links, potential tools/products, and key dependencies.

- High-fidelity calibration workflows for large scintillation detectors (energy, nuclear, homeland security, academia)

- What to do: Adopt JUNO-like multi-source calibration (241Am–13C, gamma sources), daily in-situ energy-scale tracking with cosmogenic neutrons, and dual-sensor-system cross-checks to achieve sub-percent energy-scale stability in large detectors.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Energy-scale nonlinearity models combining Birks’ law plus Cherenkov contributions.

- Likelihood-based reconstruction that fuses PMT timing and charge for spatially uniform response.

- Scheduled “daily drift” correction protocol using natural spallation neutron peaks and alpha decays (210Po/214Po).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of calibrated sources and readout electronics that support waveform capture; sufficient statistics from natural backgrounds; trained personnel for low-background operations.

- Improved signal processing and reconstruction for photon sensor arrays (software, instrumentation, medical imaging R&D)

- What to do: Port JUNO’s timing+charge likelihood reconstruction and spatial non-uniformity correction to other scintillation and Cherenkov systems (e.g., radiation monitors, laboratory spectrometers, benchtop PET testbeds).

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Open-source or modular libraries for waveform-based position/energy inference and uncertainty propagation.

- Benchmarks and QA procedures for timing/charge cross-calibration across thousands of channels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to representative waveform data; hardware that preserves timing fidelity; team expertise in probabilistic reconstruction.

- Quality assurance at scale for PMT/MCP-PMT installations (instrumentation manufacturers, test facilities, large experiments)

- What to do: Use JUNO’s dual-PMT-system approach (20-inch + 3-inch) and water-buffered mounting to validate linearity, dynamic range, and stability of large-area photodetectors pre- and post-installation.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Batch acceptance protocols using uniform light sources and distributed calibration lines.

- On-detector performance maps for spatial response equalization.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Supply chain access to PMTs/MCP-PMTs; facilities for water shielding and optical homogeneity tests.

- Low-background shielding and muon-tagging patterns (homeland security, environmental monitoring, laboratories)

- What to do: Apply JUNO’s passive (meter-scale water) + active (water Cherenkov veto, top tracker) shielding strategy to reduce cosmogenic and radiogenic backgrounds in sensitive measurement suites (e.g., trace radioactivity assays, cargo or waste assay labs).

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Modular water Cherenkov panels for muon tagging and vetoing.

- Workflow for background characterization via tagged muon samples and spallation products.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Facility space and infrastructure for shielding; maintenance for water purity; local safety/regulatory approvals.

- Reactor antineutrino spectrum cross-validation for core modeling (energy utilities, nuclear engineering R&D, safeguards labs)

- What to do: Use JUNO-style spectral distortion analysis and uncertainty budgeting as an external check on reactor antineutrino flux and spectral predictions used in core simulations and burnup analytics.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Spectral fit frameworks that incorporate detector nonlinearity, efficiency, and background systematics.

- Data–model comparison dashboards for reactor fuel-cycle stages.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Near-field or on-site neutrino detectors of modest size; data-sharing between plant operators and monitoring labs; standardized antineutrino model inputs.

- Teaching and workforce development modules on precision low-energy neutrino detection (education, academia)

- What to do: Integrate JUNO’s documented calibration, reconstruction, and systematic-control methods into graduate courses, lab practicums, and summer schools to train the next generation of detector physicists and data scientists.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Reproducible notebooks illustrating energy-scale fits, nonlinearity modeling, and spectral parameter extraction.

- Synthetic datasets emulating timing/charge reconstruction with controlled systematics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Public or sharable example datasets; institutional support for course material development.

Long-Term Applications

The following opportunities likely require further R&D, scaling, or policy frameworks before broad deployment.

- Neutrino-based reactor monitoring and safeguards at standoff distances (policy, energy, non-proliferation)

- What to do: Develop compact, high-efficiency antineutrino detectors inspired by JUNO’s calibration/stability methods to monitor reactor power and operational status from on-site to multi-kilometer standoffs for safeguards and transparency.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Portable scintillator modules with in-situ daily calibration via natural signals.

- Standardized spectral analysis pipelines that quantify deviations from declared operation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Technology miniaturization with adequate sensitivity; host-country regulatory acceptance; international standards and data governance; cost reductions.

- Supernova early warning and multi-messenger coordination (astronomy infrastructure, emergency management)

- What to do: Integrate JUNO-class detectors into SNEWS-style networks to issue rapid neutrino-based alerts providing tens of seconds lead time for optical/radio/X-ray observatories and space assets.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Automated, robust burst triggers with cross-experiment coincidence logic.

- Alert dissemination protocols and observatory scheduling APIs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High uptime and false-alarm control across the network; inter-agency protocols; public/private observatory participation.

- Precision geoneutrino mapping for Earth model constraints and potential geothermal siting insights (geoscience, energy R&D)

- What to do: Use multi-year geoneutrino datasets from JUNO-like detectors to refine crust/mantle radiogenic heat models; in the long run, assess correlations with geothermal prospecting risk models.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Joint inversions combining geoneutrino rates, seismic tomography, and geochemical priors.

- Regional background modeling workflows separating reactor and cosmogenic contributions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Long exposures for statistical power; global detector network for spatial coverage; domain-bridging models linking heat production to resource assessments.

- Medical imaging gains from fast-timing photodetector and reconstruction advances (healthcare, medtech R&D)

- What to do: Translate timing-centric light-collection and waveform reconstruction techniques to improve time-of-flight PET timing resolution and sensitivity.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Fast photodetectors (e.g., MCP-PMT or SiPM with analogous timing) plus waveform processing stacks adapted from neutrino detectors.

- Calibration protocols ensuring timing linearity and uniformity across detector panels.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Medical-grade component costs, radiation hardness and lifetime; regulatory approvals; integration with clinical workflows.

- Ultra-pure liquids and large-scale purification systems for industry (semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, advanced manufacturing)

- What to do: Adapt JUNO’s liquid scintillator handling know-how, radon suppression, and high-purity water systems to industrial ultra-clean processes.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Degassing, radiopurity verification, and continuous-monitoring toolkits.

- Materials compatibility and leaching test standards derived from large acrylic/LS experience.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Economic viability versus existing industrial solutions; tailored engineering to specific chemistries; IP/licensing.

- Massive sensor network calibration paradigms generalized to industrial IoT and monitoring (software, industrial operations)

- What to do: Apply JUNO’s “known stimulus + natural signal” cross-calibration model to fleets of distributed sensors (e.g., structural health monitoring, environmental sensor networks).

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Periodic in-situ calibration stimuli, natural-signal cross-checks, and drift-correction pipelines with uncertainty tracking.

- Fleet-level dashboards for detecting sensor drift and spatial non-uniformities.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sensors must support time-synchronized data and controlled stimuli; statistical coverage; organizational adoption.

- Global neutrino parameter constraints feeding precision cosmology and rare-event experiment design (academia, funding policy)

- What to do: Use JUNO’s improved and precisions to tighten priors in cosmological fits and optimize designs of neutrinoless double-beta decay and long-baseline experiments.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Shared likelihoods and covariance matrices for global fits; coordinated design studies using updated parameter posteriors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Continued data releases; community standards for sharing systematics; sustained funding for cross-experiment synergy.

- Advanced radiation monitoring and dosimetry with improved linearity control (health physics, nuclear facilities)

- What to do: Integrate nonlinearity modeling and sub-percent energy-scale control into next-generation dosimeters and area monitors for more accurate low-energy spectra.

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Embedded calibration sources or LED/laser systems; software for on-the-fly nonlinearity correction and QA.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Miniaturization of calibration hardware; ruggedization for field use; certification standards.

These applications build directly on JUNO’s demonstrated innovations: unprecedented 3%/MeV energy resolution in a 20 kton liquid scintillator, sub-percent energy-scale control via diversified calibration, waveform-based reconstruction across tens of thousands of PMTs, and robust background suppression with water Cherenkov vetos and top tracking. Feasibility depends on adapting these methods to scale, cost, and regulatory contexts outside a dedicated underground physics laboratory.

Glossary

- Acrylic Vessel (AV): Large transparent container made of acrylic that holds the liquid scintillator target. "The 20-kton LS target is contained within a 17.7-m-radius Acrylic Vessel (AV)"

- AmC source: A calibration source combining Am and C used to produce neutrons for energy-scale calibration. "an AmâC (AmC) source deployed at the detector center"

- Atmospheric parameters: Oscillation parameters (, ) associated with atmospheric neutrino oscillations. "referred to as the “atmospheric parameters”"

- Baseline: The source-to-detector distance relevant for observing neutrino oscillations. "At this baseline, the interference between oscillation frequencies produces a maximal spectral distortion"

- Beta decays: Radioactive decays emitting electrons/positrons; reactor antineutrinos originate from these decays. "β decays of fission products from nuclear reactors"

- Birks' law: Empirical relation describing ionization quenching in scintillators. "Birks' law"

- Central Detector (CD): The main JUNO detector volume filled with liquid scintillator used to detect neutrino interactions. "LS Central Detector (CD)"

- Cherenkov light emission: Light produced when a charged particle moves faster than light’s phase velocity in a medium. "Cherenkov light emission"

- Cosmogenic backgrounds: Background signals created by cosmic-ray interactions in/around the detector. "cosmic muons and their subsequent cosmogenic backgrounds"

- CP-violating phase: Parameter in the neutrino mixing matrix that allows violation of charge-parity symmetry. "one CP-violating phase"

- Delayed neutron capture: Neutron capture occurring a short time after an interaction, producing a delayed signal. "delayed neutron capture (\,s)"

- Energy resolution: The precision with which a detector measures particle energy, typically given as a percentage. "energy resolution of 3\% at 1\,MeV"

- Energy-scale non-linearity: Deviation of reconstructed energy from linear proportionality to true energy. "Energy-scale non-linearity, mainly from ionization quenching and Cherenkov light emission"

- Fiducial volume (FV): The inner region of the detector selected to minimize edge effects and backgrounds. "fiducial volume (FV)"

- Fission products: Nuclei produced by splitting heavy elements in reactors; their beta decays emit antineutrinos. "fission products from nuclear reactors"

- Geometrical coverage: Fraction of the detector surface covered by photodetectors, affecting light collection. "78\% total geometrical coverage"

- Inverse beta decay (IBD): Interaction where an antineutrino converts a proton into a neutron and a positron; primary detection channel at JUNO. "inverse beta decay (IBD), "

- Ionization quenching: Reduction in scintillation light yield due to dense ionization tracks in a scintillator. "ionization quenching"

- Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO): A large underground experiment in China designed to paper reactor neutrinos and neutrino properties. "The Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO)"

- Kinematic threshold: Minimum energy required for a particular interaction to occur. "Given the 1.8\,MeV IBD kinematic threshold"

- Lepton flavor mixing: Quantum mixing among electron, muon, and tau neutrino flavors described by the PMNS matrix. "lepton flavor mixing angles"

- Liquid scintillator (LS): Organic liquid that emits scintillation light when charged particles deposit energy. "JUNO is a liquid scintillator (LS) detector"

- Likelihood algorithms: Statistical reconstruction methods that maximize a likelihood function to estimate event properties. "Several likelihood algorithms"

- Majorana nature of neutrinos: Hypothesis that neutrinos are their own antiparticles. "Majorana nature of neutrinos"

- Mass eigenstates: Neutrino states with definite masses, distinct from their flavor states. "mass eigenstates , , and "

- Mass-squared differences: Differences between squared neutrino masses that determine oscillation frequencies. "neutrino mass-squared differences"

- Micro-Channel Plate (MCP): A photodetector technology using microscopic channels to amplify electron signals. "Micro-Channel Plate (MCP)"

- Monte Carlo (MC) simulations: Computational techniques using random sampling to model detector response and physics processes. "Monte Carlo (MC) simulations"

- Neutrino Mass Ordering (NMO): The sequence of neutrino mass eigenvalues (normal or inverted). "Neutrino Mass Ordering (NMO)"

- Overburden: Thickness of material above an underground detector that provides shielding from cosmic rays. "rock overburden (1800\,m water equivalent)"

- Photomultiplier tube (PMT): Sensitive light detector that converts photons to electrons and amplifies the signal. "photomultiplier tubes (PMTs)"

- Prompt positron: The positron produced immediately in IBD, forming the prompt signal. "the prompt positron"

- Scintillation light: Light emitted by a scintillator as particles deposit energy. "scintillation light"

- Scintillator non-linearity: Energy-response non-linearity intrinsic to the scintillating medium. "Scintillator non-linearity originates mainly from ionization quenching"

- Solar parameters: Oscillation parameters (, ) primarily measured using solar/reactor data. "hereafter referred to as the “solar parameters”"

- Spallation: Nuclear breakup caused by high-energy particles (e.g., cosmic muons), producing neutrons and isotopes. "muon-induced spallation"

- Spectral distortion: Oscillation-induced modulation in the measured energy spectrum of reactor antineutrinos. "maximal spectral distortion in the reactor neutrino energy spectrum"

- Standard Model: The prevailing theory describing fundamental particles and forces (excluding gravity). "beyond the Standard Model"

- Top Tracker (TT): External detector used to tag and track cosmic muons and validate muon reconstruction. "Top Tracker (TT)"

- Unitarity: Property of the mixing matrix ensuring conservation of total probability. "unitarity of lepton flavor mixing"

- Water Cherenkov Detector (WCD): Water-based detector that tags particles via Cherenkov light to shield and veto backgrounds. "Water Cherenkov Detector (WCD)"

- Water equivalent: Shielding depth expressed as an equivalent thickness of water. "water equivalent"

- Weak force: Fundamental interaction responsible for beta decays and neutrino interactions. "interact via the weak force"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.