CodeClash: Benchmarking Goal-Oriented Software Engineering (2511.00839v1)

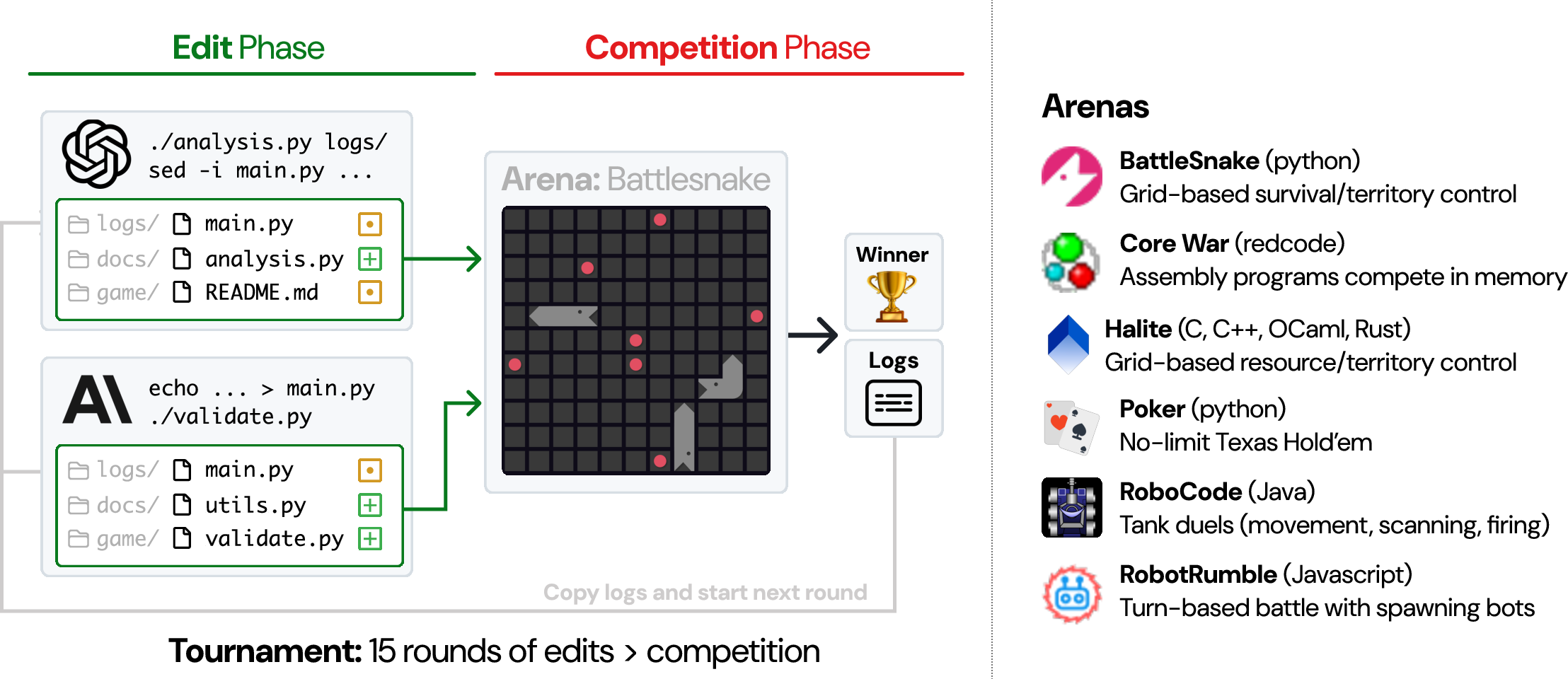

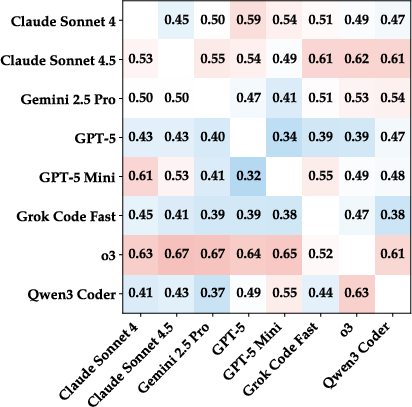

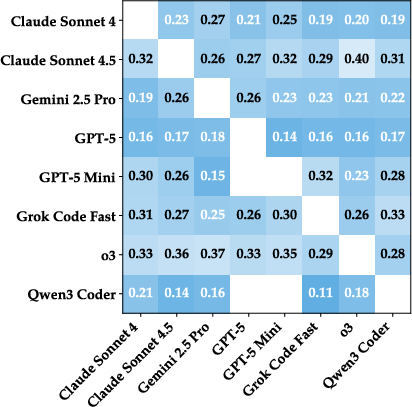

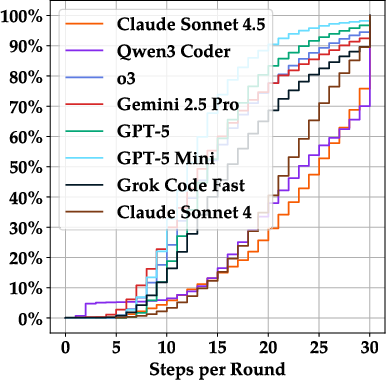

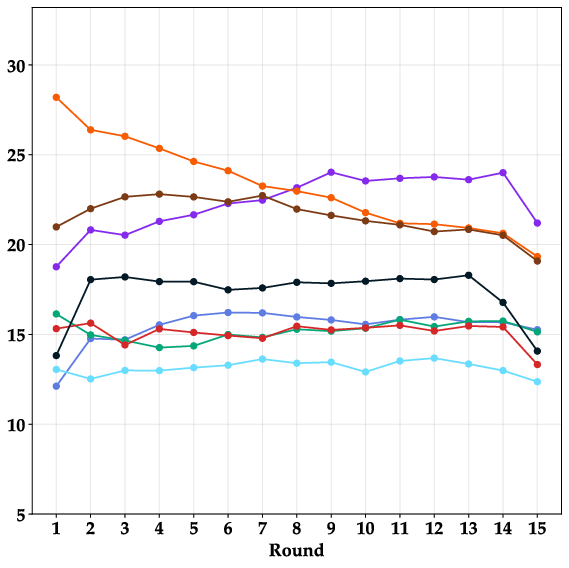

Abstract: Current benchmarks for coding evaluate LMs on concrete, well-specified tasks such as fixing specific bugs or writing targeted tests. However, human programmers do not spend all day incessantly addressing isolated tasks. Instead, real-world software development is grounded in the pursuit of high-level goals, like improving user retention or reducing costs. Evaluating whether LMs can also iteratively develop code to better accomplish open-ended objectives without any explicit guidance remains an open challenge. To address this, we introduce CodeClash, a benchmark where LMs compete in multi-round tournaments to build the best codebase for achieving a competitive objective. Each round proceeds in two phases: agents edit their code, then their codebases compete head-to-head in a code arena that determines winners based on objectives like score maximization, resource acquisition, or survival. Whether it's writing notes, scrutinizing documentation, analyzing competition logs, or creating test suites, models must decide for themselves how to improve their codebases both absolutely and against their opponents. We run 1680 tournaments (25,200 rounds total) to evaluate 8 LMs across 6 arenas. Our results reveal that while models exhibit diverse development styles, they share fundamental limitations in strategic reasoning. Models also struggle with long-term codebase maintenance, as repositories become progressively messy and redundant. These limitations are stark: top models lose every round against expert human programmers. We open-source CodeClash to advance the study of autonomous, goal-oriented code development.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces CodeClash, a new way to test AI coding systems. Instead of giving AIs small, one-time tasks (like fixing a single bug), CodeClash puts them in tournaments where they have to keep improving a codebase over many rounds to win a big, open-ended goal—like surviving longest in a game or earning the highest score. The twist: the AIs don’t play the games directly. They write and improve the code for bots that do the playing.

What questions did the researchers ask?

The authors wanted to know:

- Can AI coding systems set their own plans and improve their code over time to reach high-level goals?

- How well do they adapt to opponents who are also improving?

- Do they keep their codebases clean and organized as they iterate?

- How do they compare to skilled human programmers in competitive settings?

How did they paper it?

Think of CodeClash like a sports league for code.

- The “players” are AI coding systems. Each one has its own codebase (like a team playbook).

- A “code arena” is a competitive game environment (examples include BattleSnake, Poker, RoboCode, and others). Each AI writes a bot; then the bots battle it out according to the arena’s rules (e.g., who survives longest, who gathers the most resources, who wins more hands).

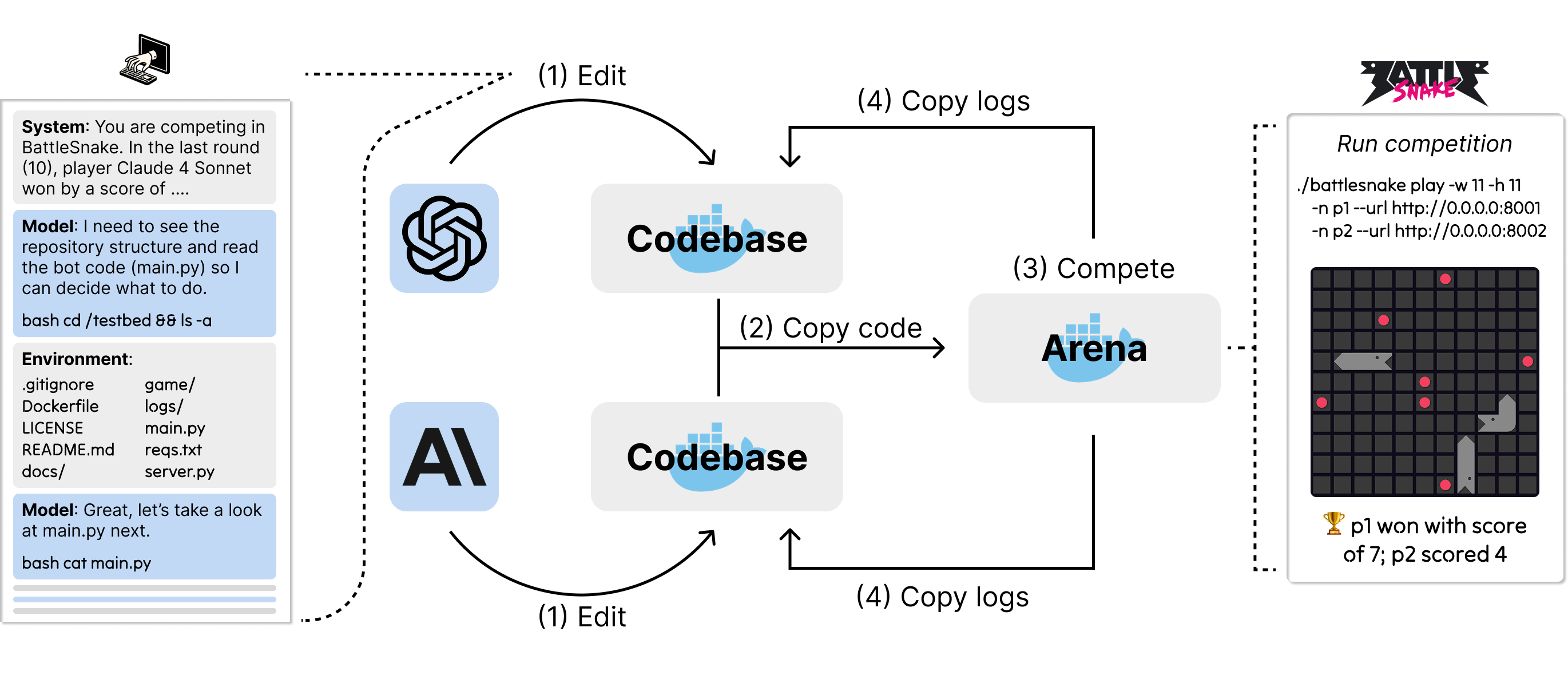

- Each match happens in rounds. Every round has two phases: 1) Edit phase: The AI updates its codebase however it wants (it can read files, write notes, add tests, run scripts, etc.). 2) Competition phase: The updated bots face off in the arena. The results and logs (records of what happened) are copied back into each AI’s codebase.

- Important constraint: The AI doesn’t “remember” past rounds unless it writes things down (in code, notes, or files). Its codebase is its memory.

- The researchers ran lots of tournaments: 8 AI models across 6 arenas, totaling 1,680 tournaments and 25,200 rounds.

Key technical ideas explained simply:

- Agent Computer Interface (ACI): This is the “hands” of the AI—basically, a safe way for the AI to run terminal commands, open files, and edit code.

- Logs: Like game replays and score sheets that show what happened each round.

- Elo rating: A scoring system (like in chess) that estimates how strong a player is based on who they beat.

What did they find, and why does it matter?

Here are the main takeaways from the experiments:

- Different styles, same weaknesses:

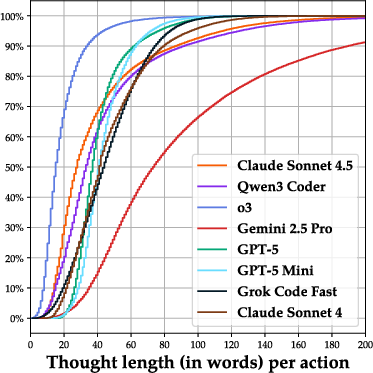

- AIs showed very different “coding personalities.” Some made small, careful edits; others changed lots of files. Some wrote long thoughts; others were brief.

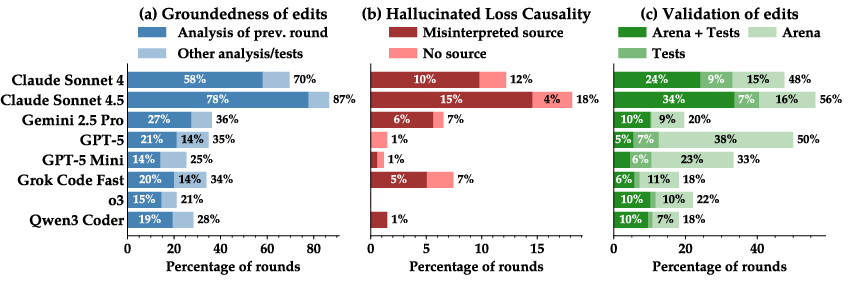

- Despite the variety, they shared important limitations: weak strategy, shallow analysis of feedback, and poor long-term planning.

- Trouble learning from results:

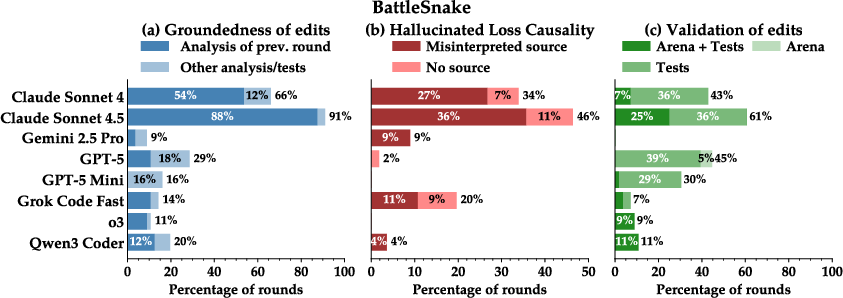

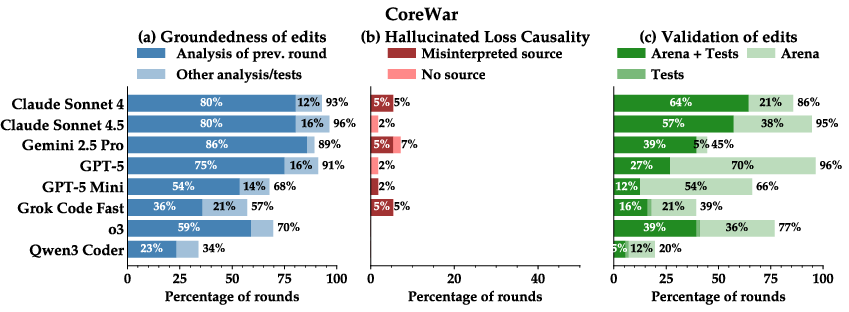

- Many AIs didn’t deeply analyze the logs (game replays) to figure out why they won or lost.

- They often guessed wrong about the cause of failure (the paper calls this “hallucinating” reasons).

- They frequently made changes without testing whether those changes really helped.

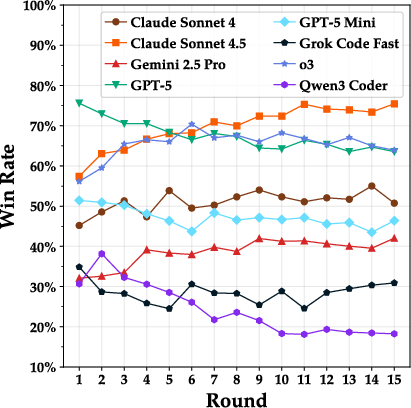

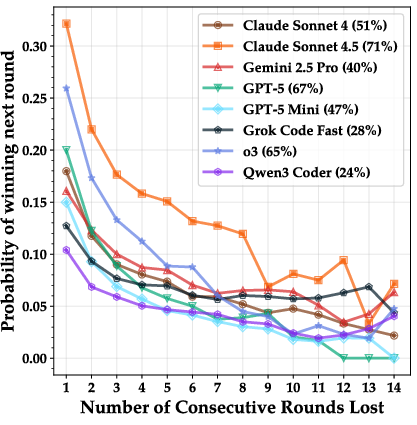

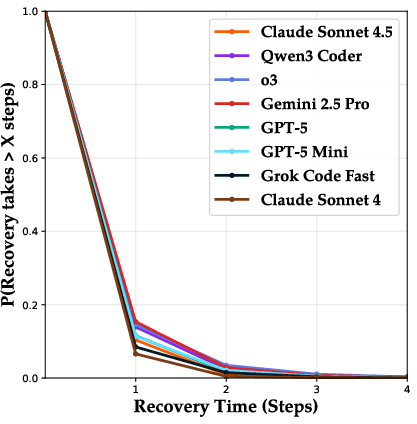

- Hard to bounce back:

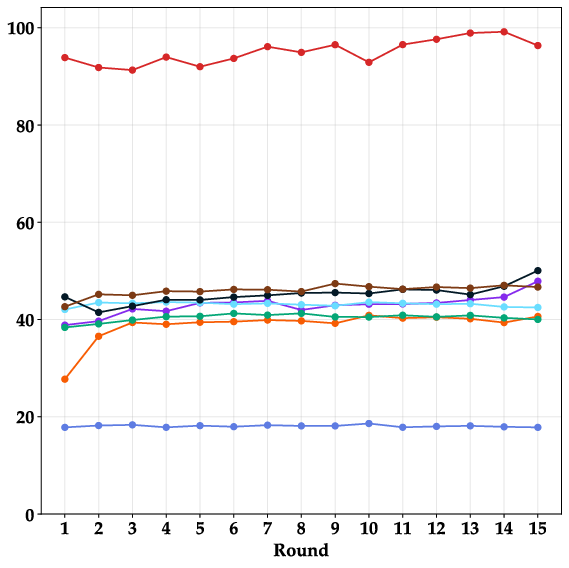

- After losing a round, even the stronger AIs rarely “come back” in the next round. Their chance of winning often dropped sharply after a loss, suggesting they struggle to rethink or pivot their strategy.

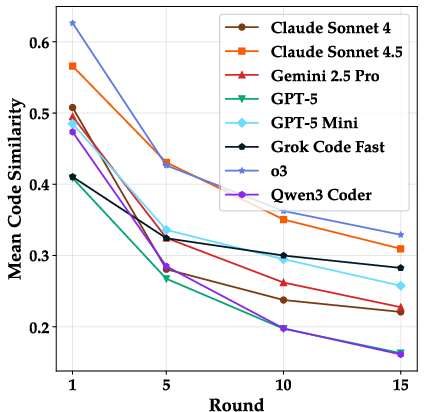

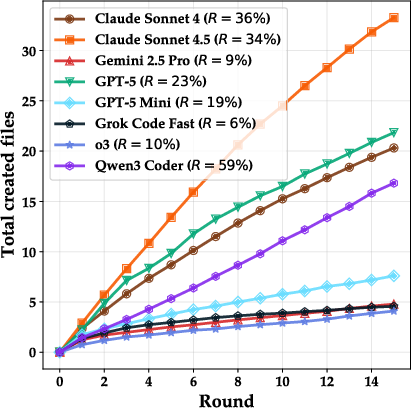

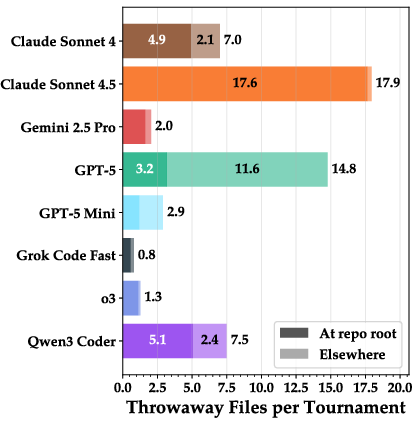

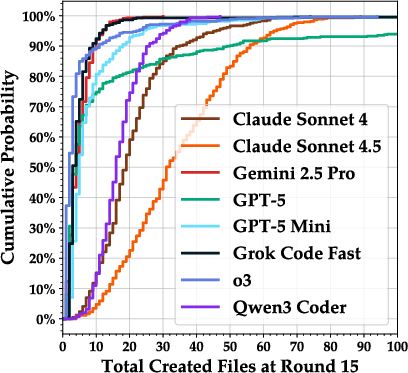

- Messy codebases over time:

- Instead of cleaning up and improving structure, many AIs kept creating more files round after round, often with repetitive names and lots of “throwaway” scripts they never used again.

- This shows weak habits in code maintenance and organization—important skills in real software projects.

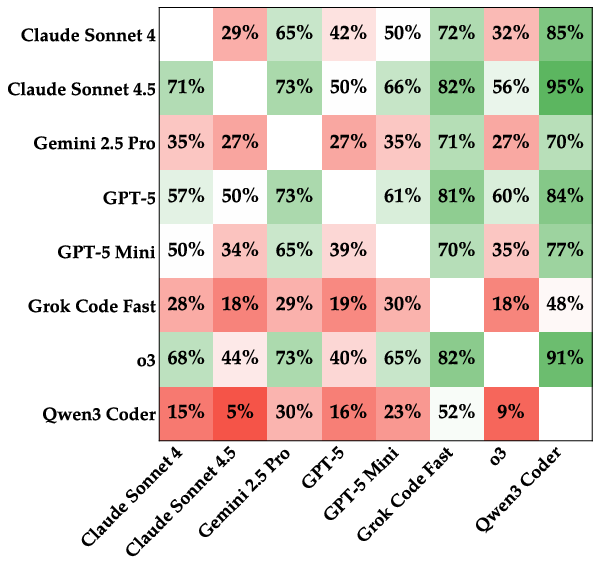

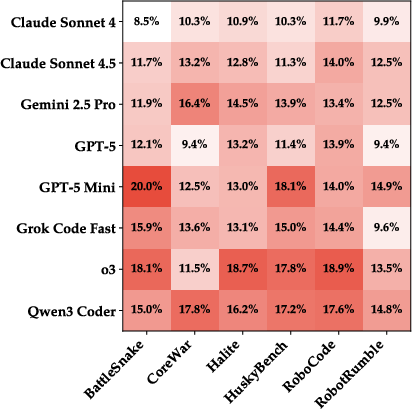

- No single “best everywhere” model:

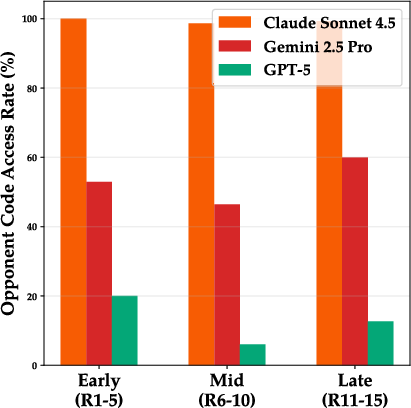

- One model (Claude Sonnet 4.5) ranked highest on average, but it did not dominate every arena. Different arenas stress different skills.

- Humans still win:

- Against an expert human-made bot in one arena (RobotRumble), the best AI model lost every single round—even across 37,500 simulations. This shows a big gap still exists between top AI systems and skilled human programmers in competitive, evolving environments.

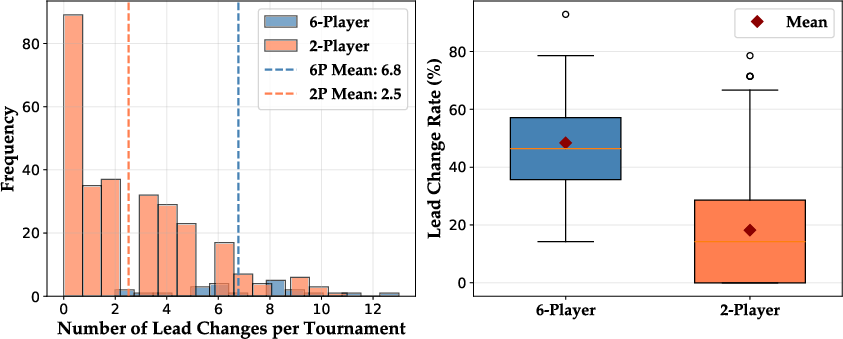

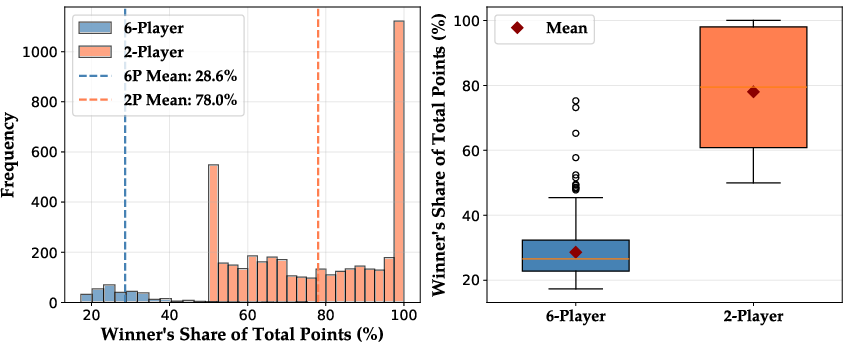

- Multi-player chaos:

- With more than two players, tournaments got more volatile—leaders changed more often and wins were spread out—highlighting how messy and dynamic real competition can be.

Why this matters:

- Real-world software isn’t just “fix bug X.” It’s about setting goals, adapting to feedback, beating competitors, and keeping code clean over time. CodeClash tests these tougher, more realistic skills—where current AIs still struggle.

What could this change in the future?

The authors release CodeClash as open source so others can use it to paper and improve AI coding agents. Potential impacts:

- Better training for autonomous coding agents: AIs can learn from continuous, rich feedback (not just pass/fail tests), including self-play and opponent adaptation.

- Stronger analysis tools: Future systems may build better log analyzers, test harnesses, and self-checks—so they stop guessing and start measuring.

- Improved code hygiene: Research can focus on teaching AIs to maintain clean, reusable codebases over many iterations.

- More realistic benchmarks: Beyond simple unit tests, future arenas could simulate complex, real-world goals (like reducing costs, increasing reliability, or handling emergencies).

- Human–AI collaboration: CodeClash could also be used to paper how humans and AIs co-develop strategies and code together.

In short, CodeClash shows that today’s AI coders can be creative and competent in short bursts, but they still struggle with big-picture strategy, careful learning from feedback, and long-term code health. It sets the stage for building the next generation of AI systems that can plan, adapt, and improve like experienced software engineers.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of what the paper leaves missing, uncertain, or unexplored, phrased to be actionable for future research.

- External validity: It is unclear how performance in CodeClash’s game-like arenas correlates with real-world software engineering outcomes (e.g., user retention, revenue, reliability). Establish predictive validity to real enterprise SWE tasks.

- Arena diversity and complexity: The six arenas are relatively small and self-contained. Investigate larger, more complex, multi-objective environments (e.g., city-scale simulations, cybersecurity, distributed systems) and measure whether rankings and behaviors transfer.

- Human baselines: Human comparison is limited to a single bot in RobotRumble. Run systematic human baselines across all arenas (including open-source and closed-source human bots), with varied skill levels and adaptation between rounds.

- Multimodal feedback: Logs are text-only; many arenas have rich visual states. Evaluate Vision-LLMs with graphical logs, state visualizations, and replay videos to test whether multimodal feedback improves diagnosis and strategy.

- Memory design: Agents only have “codebase-as-memory” with no persistent external memory. Study the impact of explicit long-term memory (e.g., vector stores, knowledge graphs, retrospectives) on adaptation and codebase organization.

- Scaffold dependence: Results use mini-SWE-agent with bash-only tooling. Quantify how different agent scaffolds (OpenHands, SWE-agent, tool suites, planning/execution loops) change performance, maintenance behavior, and strategic reasoning.

- Turn budget sensitivity: The edit phase is capped at 30 turns. Analyze sensitivity to turn budgets, token budgets, and latency constraints; determine fairness and whether some models benefit disproportionately from longer interaction budgets.

- Opponent transparency: Strategic opacity is default; a small ablation permits read-only access to prior opponent code. Systematically vary degrees of transparency (logs-only, API traces, full code, runtime introspection) and measure effects on meta-strategy, counterplay, and deception.

- Multi-agent dynamics: Multi-player tournaments were tested in one arena (Core War) with six models. Extend to more arenas and player counts; measure coalition formation, positional play, risk management, and instability in rankings under many-player dynamics.

- Generalization across arenas: Rankings differ by arena (no single model dominates). Quantify cross-arena generalization via out-of-domain arenas and parameterized variants (maps, rules, resource distributions) to test robustness and overfitting.

- Starter code dependence: All experiments use provided starter codebases. Evaluate cold-start conditions, varying starter quality, and adversarial or misleading starters to understand sensitivity to initial code structure and documentation.

- Data contamination: Models may have prior training exposure to arenas, strategies, or public bots. Audit and control for contamination to ensure a fair benchmark (e.g., new custom arenas, private rulesets, provenance tracking).

- Evaluation granularity: Metrics focus on win rates and Elo/TrueSkill. Add fine-grained measures: adaptation speed per round, sample efficiency per simulation, comeback robustness, regression frequency, ablation-specific improvements, and causal attribution of code changes to outcomes.

- Validation methodology: LM-as-a-judge annotations rely on a single model (GPT-5). Establish judge reliability via multi-LLM ensembles and human annotation; measure inter-rater agreement, calibration, and bias.

- Log analysis capability: Agents receive gigabytes of logs, which exceed typical LM context limits. Explore scaffolds for scalable log ingestion (summarization pipelines, streaming analytics, tool-based parsing) and evaluate their impact on grounded decision-making.

- Maintainability metrics: The paper observes messy codebases (file proliferation, redundancy, throwaways) but lacks standardized maintainability metrics. Develop and validate quantitative measures (cohesion/coupling, dependency graphs, duplicate code, file hygiene indices).

- Interventions for hygiene: No experiments test interventions (linters, formatters, structure templates, cleanup policies) to reduce repository entropy. Evaluate whether tooling or prompts for refactoring/cleanup improve long-run maintainability and performance.

- Unit test culture: Models seldom write or use tests. Design arenas/scaffolds that reward test coverage, differential testing, and self-play validations; quantify how testing behaviors affect regression rates and win trajectories.

- Strategy reassessment: Models struggle to recover after losses. Test scaffolds that enforce structured retrospectives, hypothesis tracking, A/B comparisons, and backtesting; measure improvements in comeback probabilities and strategic pivot quality.

- Opponent modeling: Despite transparent code ablation, models rarely exploit opponent weaknesses. Build explicit opponent-modeling pipelines (behavioral profiling, strategy classification, counter-strategy generation) and evaluate payoffs.

- Runtime fairness and resources: The reported runtime is extremely large; costs and latencies may differ across model providers. Control for resource heterogeneity (rate limits, context windows, throughput), and report standardized resource-normalized performance.

- Token/trace logging: The paper does not report per-round token usage, thought lengths by arena, or action traces alignment with outcomes. Release richer traces and paper correlations between reasoning styles, token budgets, and competitive success.

- Security and sandboxing: The bash-based interface can pose security risks in open-source replication. Document sandboxing guarantees, network isolation, and reproducibility practices; explore secure agent tooling that permits broader experimental sharing.

- Reproducibility and seeds: Arena randomness, seeds, and simulation parameters are not fully specified. Provide deterministic seeds, variance estimates, and robust statistical protocols (e.g., power analyses) to ensure replicable comparisons.

- Leaderboards and lifecycle: Only one arena has a public leaderboard suitable for human comparisons. Establish official leaderboards for all arenas with versioned releases, periodic refreshes, and anti-overfitting mechanisms (hidden test arenas, rotating maps).

- Training on CodeClash: The paper suggests but does not test self-play/RL or pretraining on edit traces. Quantify how training on CodeClash artifacts changes model rankings and behaviors, and whether gains transfer to standard SWE benchmarks (e.g., SWE-bench).

- Cross-language support: Analysis of solution diversity is limited to Python main.py in BattleSnake. Expand language coverage and compare semantic diversity via language-agnostic code embeddings and behavioral metrics (not just difflib).

- Behavior-to-outcome attribution: Current analyses infer ungrounded edits and hallucinations but lack causal links. Implement controlled A/B deployments and causal inference pipelines to attribute performance changes to specific code modifications.

- Prompt design: System prompts offer high-level suggestions but no structured guidance. Systematically vary prompts (e.g., “coach” prompts, tool-use directives, checklists) and quantify their effects on grounding, validation, and repository hygiene.

- Ethical/game-specific constraints: Some arenas may reward deceptive or brittle strategies. Study alignment and robustness: ensure strategies remain fair, transparent, and resilient to rule changes; assess whether high-ranked models overfit to loopholes.

- Model coverage: Only eight frontier models are tested. Extend to smaller open-source models and distilled agents to understand scaling trends, cost-performance trade-offs, and accessibility of the benchmark for broader communities.

- Tournament design: Rounds are fixed at 15 per tournament. Analyze sensitivity to round count, match length, and simulation count (per round) on ranking stability and learning dynamics.

- Opponent evolution: Opponents are static unless both are LMs. Introduce “evolving human” or “evolving scripted” baselines to test co-evolution dynamics and prevent stagnation in relative performance signals.

- Code execution introspection: Agents cannot inspect runtime states beyond logs. Evaluate tooling that surfaces richer runtime introspection (profilers, debug visualizations, telemetry) and test if it reduces hallucinations and improves grounded edits.

Glossary

- A/B test: A controlled experiment comparing two variants to assess impact on a metric or behavior. "A/B test results"

- Adversarial adaptation: The process of changing strategies or code in response to opponents in a competitive setting. "Adversarial adaptation. CodeClash's uniquely multi-player, head-to-head setting adds a new layer of complexity to coding evaluations."

- Agent Computer Interface (ACI): A scaffold that lets an LM interact with a codebase through actions like running shell commands. "Player refers to an LM equipped with an Agent Computer Interface (ACI) or scaffold that enables it to interact with a codebase~\citep{yang2024sweagentagentcomputerinterfacesenable}."

- Agent scaffold: The framework and tools surrounding an LM that structure how it performs tasks and interacts with code. "We intentionally decide against using tool-heavy scaffolds such as SWE-agent or OpenHands~\citep{wang2025openhandsopenplatformai}, as they are often optimized for models and benchmarks."

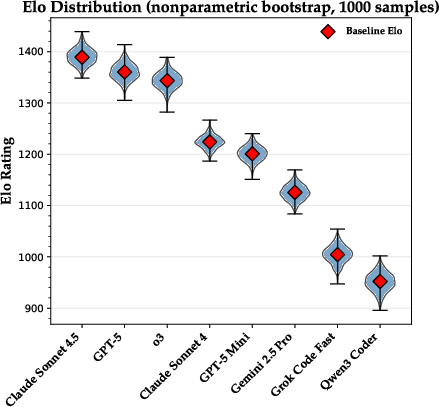

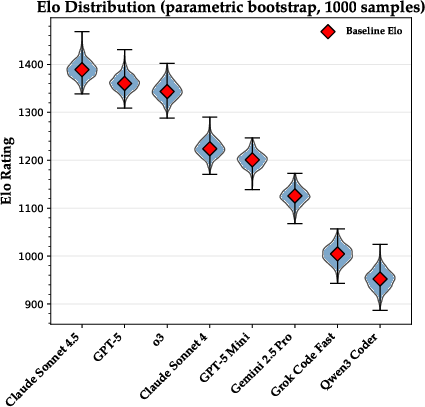

- Bootstrapping (parametric and non-parametric): Statistical resampling methods for estimating uncertainty or validating results by repeatedly sampling data. "We validate rank stability and our statistical treatment with both parametric and non-parametric bootstrapping experiments and observe more than 98\% pairwise order agreement."

- Cascading failures: Error patterns where one failure triggers subsequent failures, compounding problems in an agent system. "This stands in stark contrast to earlier findings of 'cascading failures' in agent systems~\citep{yang2024sweagentagentcomputerinterfacesenable,pan2025trainingsoftwareengineeringagents}"

- Code arena: A platform that executes multiple codebases against each other and produces competitive outcomes. "their codebases compete head-to-head in a code arena"

- Codebase-as-memory: A design where the only persistent memory across rounds is what the agent explicitly writes into the repository. "Codebase-as-memory: players have no explicit memory of actions from previous rounds."

- Comeback probability: The chance of winning the next round after a loss streak, used to assess recovery ability. "comeback probability (win probability of the next round)"

- difflib.SequenceMatcher: A Python utility to compute similarity between sequences, here used to measure code similarity. "using Python's difflib.SequenceMatcher~\citep{ratcliff1988pattern}"

- Elo scores: A rating system that models relative skill based on head-to-head outcomes. "we use Elo scores with a base rating of and a slope of $400$ to quantify the overall strength of each model."

- Filename redundancy metric: A measure of repeated filename patterns, indicating organizational redundancy in repositories. "We quantify this effect through the filename redundancy metric (the fraction of files sharing name prefixes with other files)"

- Hallucination (LLM): When a model asserts ungrounded or incorrect explanations or facts. "Even top models hallucinate reasons for failure or modify code without confirming if these changes meaningfully improve performance."

- LM-as-a-judge: Using a LLM to evaluate or annotate other models’ behaviors or outputs. "Using LM-as-a-judge, we annotate players' trajectories with answers to three questions"

- Log-based feedback: A setup where post-round logs are the sole source of new information for subsequent edits. "Log-based feedback: after each competition phase, the results and logs are copied into each player's codebase as the sole source of new information."

- Maximum likelihood fit: Estimating model parameters by maximizing the probability of observed outcomes. "we perform a more rigorous maximum likelihood fit to the win rates."

- Mini-SWE-agent: A lightweight ACI that limits agents to bash interactions for code editing and analysis. "we use mini-SWE-agent, an agent computer interface (ACI) that enables an LM to interact with a codebase by issuing bash actions to a terminal~\citep{yang2024sweagentagentcomputerinterfacesenable}."

- Open-ended objectives: Goals without fixed correctness tests, requiring agents to define and pursue their own improvement strategies. "Open-ended objectives. CodeClash departs from the traditional reliance on unit tests or implementation correctness to measure success."

- ReAct: A prompting method where models interleave reasoning (thought) and acting (tool use) in steps. "a ReAct~\citep{yao2023reactsynergizingreasoningacting} style response"

- Self-crafted memory: Knowledge that agents explicitly record in their codebases for future rounds, in lieu of persistent hidden memory. "Self-crafted memory. As mentioned in Section~\ref{sec:codeclash:formulation}, CodeClash does not maintain persistent memory for models across rounds; only ephemeral, within-round memory exists."

- Self-directed improvement: Autonomous planning and execution of code changes without prescriptive instructions. "Self-directed improvement. Beyond a brief description of the environment and arena, the initial system prompt provided to each player at the start of every edit phase contains no guidance beyond high level suggestions about how to enhance its codebase."

- Self-play: Training or evaluation where agents improve by competing against versions of themselves or one another. "via self-play and reinforcement learning~\citep{zelikman2022star}"

- Strategic opacity: Hiding opponents’ code to force reasoning from indirect signals like outcomes and logs. "Strategic opacity: players cannot see each other's codebases, though we explore lifting this restriction in Section~\ref{sec:results:ablations}."

- SWE-agents: Software-engineering agents powered by LMs that autonomously modify and manage codebases. "players (LMs as SWE-agents) compete in programming tournaments spanning multiple rounds."

- Throwaway files: Files created during a round that are never reused or referenced later, indicating waste or disorganization. "We quantify these throwaway files in Figure~\ref{fig:bar_chart_throwaway_files}"

- TrueSkill rating system: A Bayesian skill rating system suitable for multi-player competitions. "we use the TrueSkill rating system~\citep{herbrich2006trueskill} since Elo and win rate are limited to one-on-one settings."

- Vision LLMs (VLMs): Models that process both visual and textual inputs for reasoning or control. "We don't explore Vision LLMs (VLMs) in this work."

Practical Applications

Overview

Below are practical, real-world applications that build directly on CodeClash’s findings, methods, and artifacts. Each item notes sectors, potential tools/products/workflows, and feasibility dependencies, grouped as Immediate Applications and Long-Term Applications.

Immediate Applications

These can be piloted or deployed now using the released toolkit, logs, and evaluation methodology.

- Bold-faced bakeoffs for agentic coding systems in CI/CD

- Sectors: Software, MLOps, DevTools

- What: Use CodeClash tournaments as a pre-merge or pre-release gate to evaluate autonomous coding agents (or model updates) on open-ended, multi-round objectives rather than unit-test-only tasks.

- Tools/workflows:

- “Agent Arena” job in CI that spins up 1–v–1 tournaments on selected arenas.

- Use Elo/TrueSkill, comeback probability, and per-round win-rate trends as release criteria.

- Dashboards tracking codebase hygiene (file growth, redundancy, throwaway rate).

- Dependencies/assumptions: Sandbox compute; deterministic seeds for reproducibility; cost control for multi-round runs; evaluation arenas approximating relevant product goals.

- Model/vendor selection via CodeClash-style procurement evaluation

- Sectors: Software, Finance, Regulated industries (for procurement)

- What: Compare coding copilots/agents across vendors using standardized tournaments to assess strategic adaptation, validation discipline, and code maintainability under pressure.

- Tools/workflows:

- Internal benchmark pack with curated arenas and acceptance thresholds (e.g., “must validate ≥50% of changes; throwaway files ≤X per tournament”).

- Dependencies/assumptions: Access to comparable model interfaces; standardized compute budgets; anti-benchmark-gaming procedures.

- Agent hygiene monitors integrated into repositories

- Sectors: Software, DevTools

- What: Deploy “agent lint” that computes the paper’s hygiene metrics in real time:

- File creation rate across rounds, filename redundancy, throwaway file ratio, root-directory pollution.

- Tools/products:

- Repo-level bot that comments on PRs with hygiene KPIs and suggests auto-cleanups.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Access to agent edit logs; clear thresholds that do not penalize healthy exploration.

- Log-grounded analysis assistants

- Sectors: Software, AIOps, DevOps

- What: Lightweight assistants that parse arena logs and verify that proposed code changes are grounded in evidence (addressing the frequent hallucinated failure analyses observed).

- Tools/workflows:

- Scripts to summarize loss-causing events; “evidence trace” linking edits ↔ log snippets; automated unit/simulation test generation.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Structured log formats; reliable parsers; guardrails to prevent overfitting to superficial signals.

- Validation-before-deploy orchestrators for agents

- Sectors: Software, DevOps, Testing

- What: Enforce “simulate or test” gates since most models deployed unvalidated changes in many rounds.

- Tools/workflows:

- Auto self-play across code versions; regression checks; minimal unit tests scaffolding generated per change.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Fast local simulation harnesses; budget for repeated runs; clear pass/fail thresholds.

- Courseware and hackathons for goal-oriented coding

- Sectors: Education, Workforce training

- What: Teach iterative software improvement with adversarial objectives (BattleSnake, RoboCode, Poker) to build skills in strategy, experimentation, and log-driven iteration.

- Tools/workflows:

- Classroom tournament kits; grading based on Elo gains, code hygiene, and documentation quality.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Instructor support; sandbox infra; starter code and rubrics.

- Research testbed for strategic reasoning and adaptation

- Sectors: Academia (CS, HCI, ML), Industrial Research

- What: Run controlled studies on phenomena exposed by the paper (poor comeback rates, ungrounded edits, divergent development styles).

- Tools/workflows:

- Ablations (opponent code visibility, turn budgets, log types); interventional prompts; external memory tools; analysis of per-round drift and diversity.

- Dependencies/assumptions: IRB for human-baselines if used; compute for large tournament grids.

- Multi-player volatility testing for agents

- Sectors: Software, Multi-agent systems

- What: Stress-test agents under 3+ player volatility (higher lead changes, lower point concentration) to evaluate robustness beyond 1–v–1.

- Tools/workflows:

- TrueSkill-based ranking; coalition/responsiveness probes; risk preference diagnostics.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Scalable arenas; metrics beyond win rate (e.g., consistency and risk-adjusted performance).

- Robotics/control code sandboxes

- Sectors: Robotics, Simulation

- What: Use tournament-based control code evaluation (e.g., RoboCode-like engines) to compare iterative controller updates.

- Tools/workflows:

- Simulation harnesses; self-play of controller variants; telemetry-to-code feedback loops.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Realistic simulators; domain-specific safety constraints.

- Dataset curation from released artifacts

- Sectors: Academia, Model training

- What: Build datasets for supervised fine-tuning on edit grounding, log reading, and validation behaviors using the open-source traces, logs, and repository histories.

- Tools/workflows:

- “Edit justification” labels; contrastive pairs (validated vs unvalidated edits); agents’ thoughts/actions mining.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Licensing compliance; balanced sampling across arenas; privacy review for any added logs.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling, model improvements, or stronger safety/compliance frameworks.

- Autonomous product engineering agents achieving business KPIs

- Sectors: Software, Product/Growth, E-commerce

- What: Agents that decompose high-level goals (retention, revenue, latency) into experiments, implement changes, analyze production telemetry, and iterate.

- Tools/products:

- “Goal-to-experiment” planners; production-sim A/B arenas; KPI-grounded change validators.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Reliable strategic reasoning (currently weak); robust memory beyond codebase-as-memory; strong safety and rollback systems; business metric instrumentation.

- Continuous self-improvement via self-play and RL

- Sectors: ML Platforms, Agent R&D

- What: Train agents with perpetual learning signals from evolving opponents and non-binary objectives, rather than static unit tests.

- Tools/workflows:

- Curriculum arenas; population-based training; safe exploration policies; offline-to-online RL.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Substantial compute; reward shaping that avoids degenerate strategies; anti-overfitting to specific arenas.

- Human–AI co-development loops with formal guardrails

- Sectors: Software, Regulated industries

- What: Agents propose code, humans review/steer strategic direction, and tournaments act as objective safety/performance validators before production.

- Tools/products:

- “Agent Coach” UIs; rationale checkers; gated deploy with red-team arenas; audit trails.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Traceability standards; liability clarity; organizational buy-in.

- Sector-specific competitive sandboxes

- Healthcare: Scheduling/triage policy tournaments optimizing wait times or outcomes (requires HIPAA-compliant synthetic data, clinical oversight).

- Energy: Grid dispatch or bidding strategy arenas (requires high-fidelity simulators, safety interlocks).

- Finance: Strategy tournaments in realistic market simulators for pre-trade validation (requires compliance, robust risk constraints).

- Cybersecurity: Red/blue competitive code arenas for continuous hardening (requires safe malware sandboxes, disclosure policies).

- Education: Adaptive learning algorithms that compete on engagement/learning metrics in sim before classroom deployment.

- Dependencies/assumptions: High-fidelity domain simulators; regulatory and ethics frameworks; realistic data and guardrails.

- Opponent modeling and counter-strategy toolchains

- Sectors: Cybersecurity, Competitive strategy, Games/eSports

- What: Dedicated modules that infer opponent patterns from logs/code and produce tailored countermeasures (paper’s ablations suggest room for growth).

- Tools/workflows:

- Automated scouting reports; exploit detection; counter-policy synthesis.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Access to opponent behaviors or artifacts; avoiding privacy/IP violations; generalization beyond overfitting.

- Multi-modal feedback for agents (logs + visuals)

- Sectors: Robotics, HCI, VLM Systems

- What: Agents that learn from game replays/visual traces alongside text logs to improve spatial/temporal reasoning and debugging.

- Tools/workflows:

- Replay parsers; vision-language alignment to code edits; visual-causal analysis.

- Dependencies/assumptions: VLM robustness; synchronized data capture; eval protocols for multimodal grounding.

- Maintainability-first agent architectures

- Sectors: Software, DevTools

- What: Architectures that internalize maintainability KPIs (file structure convergence, reuse, doc/tests growth) to avoid the observed “messy codebase drift.”

- Tools/products:

- “Repository homeostasis” objectives; automated archive/refactor passes; memory substrates beyond raw files (e.g., structured knowledge stores).

- Dependencies/assumptions: Reliable long-horizon planning; safe refactoring at scale; developer acceptance.

- Governance and certification frameworks for autonomous coding

- Sectors: Policy, Compliance, Standards bodies

- What: Certification that agents meet thresholds on grounding, validation, maintainability, and resilience metrics (comeback rates) before deployment in critical systems.

- Tools/workflows:

- Standardized CodeClash-like suites; transparent scorecards; regulatory sandboxes.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Consensus standards; third-party auditors; periodic re-certification to prevent drift.

- Enterprise “Agent Arena” platforms (SaaS)

- Sectors: DevTools, Platform Engineering

- What: Managed service offering curated arenas, scoring, telemetry, and integrations (GitHub/GitLab/Jenkins) to operationalize agent evaluation and training.

- Tools/products:

- Sector-specific arena packs; KPI dashboards; policy-as-code gates; team collaboration features.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Data security; on-prem options; cost controls for large tournaments.

- Resilience engineering for agents

- Sectors: Safety-critical software, SRE

- What: Systematically improve agents’ ability to recover from losses (the paper shows steep drop-offs) using diagnostics for hypothesis revision and exploration strategies.

- Tools/workflows:

- “Comeback drills” scenarios; exploration-exploitation tuners; strategic hypothesis testing frameworks.

- Dependencies/assumptions: Better meta-reasoning; telemetry on causal determinants of failure; risk-aware exploration limits.

Notes on Key Assumptions and Dependencies

- Domain fidelity: Arenas must approximate real objectives to transfer insights to production.

- Costs/latency: Multi-round tournaments are compute-intensive; budget and time constraints matter.

- Safety/sandboxing: Agents should be restricted from sensitive systems; rigorous guardrails needed.

- Evaluation integrity: Prevent benchmark overfitting and gaming; randomization and hidden tests help.

- Memory and multi-modality: Many real tasks need richer, durable memory and visual/temporal feedback.

- Human baselines: Paper shows top models lost to expert humans—human-in-the-loop and oversight remain critical in the near term.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.