PhysHSI: Towards a Real-World Generalizable and Natural Humanoid-Scene Interaction System

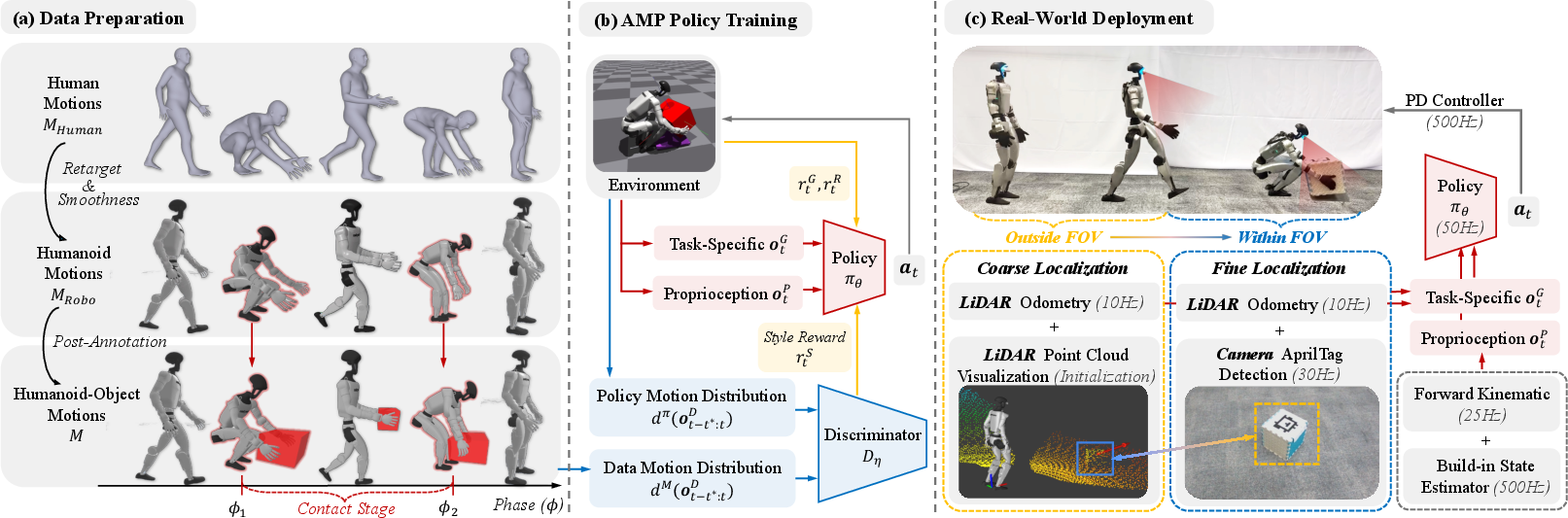

Abstract: Deploying humanoid robots to interact with real-world environments--such as carrying objects or sitting on chairs--requires generalizable, lifelike motions and robust scene perception. Although prior approaches have advanced each capability individually, combining them in a unified system is still an ongoing challenge. In this work, we present a physical-world humanoid-scene interaction system, PhysHSI, that enables humanoids to autonomously perform diverse interaction tasks while maintaining natural and lifelike behaviors. PhysHSI comprises a simulation training pipeline and a real-world deployment system. In simulation, we adopt adversarial motion prior-based policy learning to imitate natural humanoid-scene interaction data across diverse scenarios, achieving both generalization and lifelike behaviors. For real-world deployment, we introduce a coarse-to-fine object localization module that combines LiDAR and camera inputs to provide continuous and robust scene perception. We validate PhysHSI on four representative interactive tasks--box carrying, sitting, lying, and standing up--in both simulation and real-world settings, demonstrating consistently high success rates, strong generalization across diverse task goals, and natural motion patterns.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What is this paper about?

This paper introduces a system called PhySHSI that helps humanoid robots interact with everyday scenes in a natural, human-like way. Think of tasks like carrying a box, sitting on a chair, lying down on a bed, or standing up. The goal is to make robots move smoothly and realistically while understanding where objects are, both indoors and outdoors.

Objectives: What questions did the researchers ask?

The researchers wanted to know:

- How can we teach a humanoid robot to perform different everyday interactions naturally, not like a stiff machine?

- How can we make the robot’s skills work in many different places with different objects, not just in a fixed lab setup?

- How can the robot reliably “see” and find objects it needs to interact with, even when they’re far away or briefly out of view?

Methods: How did they build and train the system?

The system has two parts: learning in simulation (practice) and working in the real world (deployment). Here’s the idea in simple terms.

1) Learning natural movements in simulation

- Motion capture (MoCap) data: This is like recording how real humans move (walking, sitting, picking up things). The team used large human motion datasets and “retargeted” them to a robot’s body, so the robot could learn the style of human motion.

- Adversarial Motion Priors (AMP): Imagine a “judge” network that looks at the robot’s movements and decides whether they look human-like or not. The robot learns to fool the judge by moving more like a human while also completing the task (e.g., carry the box to a goal).

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): This is trial-and-error learning. The robot tries things, gets rewards for doing well (e.g., moving toward a chair, lifting a box), and improves over time.

- Smarter starts (Hybrid RSI): Instead of always starting from the same pose, the robot sometimes starts from points taken from the motion data (like already near the chair) and sometimes from fully random scenes. This helps it learn long tasks faster and generalize better.

- Smoothness and stability: They added training rules that discourage jerky or unnatural movements, so the robot’s motions stay smooth enough for real hardware.

2) Seeing and localizing objects in the real world

The robot combines two kinds of onboard sensors to find objects reliably:

- LiDAR: A laser sensor that measures distance and helps the robot know where it is in space over time (this tracking is called “odometry”). Think of it as a rough compass and map that works at long distances.

- Camera + AprilTag: The camera looks for a simple sticker marker (an AprilTag, like a high-tech QR code). When the tag is visible, the robot can get a very accurate object position.

This forms a “coarse-to-fine” strategy:

- Coarse stage (far away): Use LiDAR and odometry to keep a rough estimate of where the object is. This helps the robot navigate toward it even if the camera can’t see it yet.

- Fine stage (close up): Once the tag appears in the camera view, switch to accurate camera-based localization for precise actions like grasping or sitting.

They also handled tricky cases:

- Static vs. dynamic objects: A chair is static (doesn’t move). A box becomes dynamic when the robot picks it up—if it leaves the camera’s view, the system safely “masks” (temporarily ignores) its exact pose and relies on the robot’s body sense to finish the task.

- Domain randomization: During simulation training, they added noise and random delays to mimic the messy real world, helping the robot adapt when deployed.

Hardware used: A Unitree G1 humanoid robot equipped with a Livox LiDAR and a RealSense camera. Everything runs onboard on a compact computer (Jetson Orin NX), so the system is portable.

Findings: What worked and why it’s important

Here are the main results the team observed:

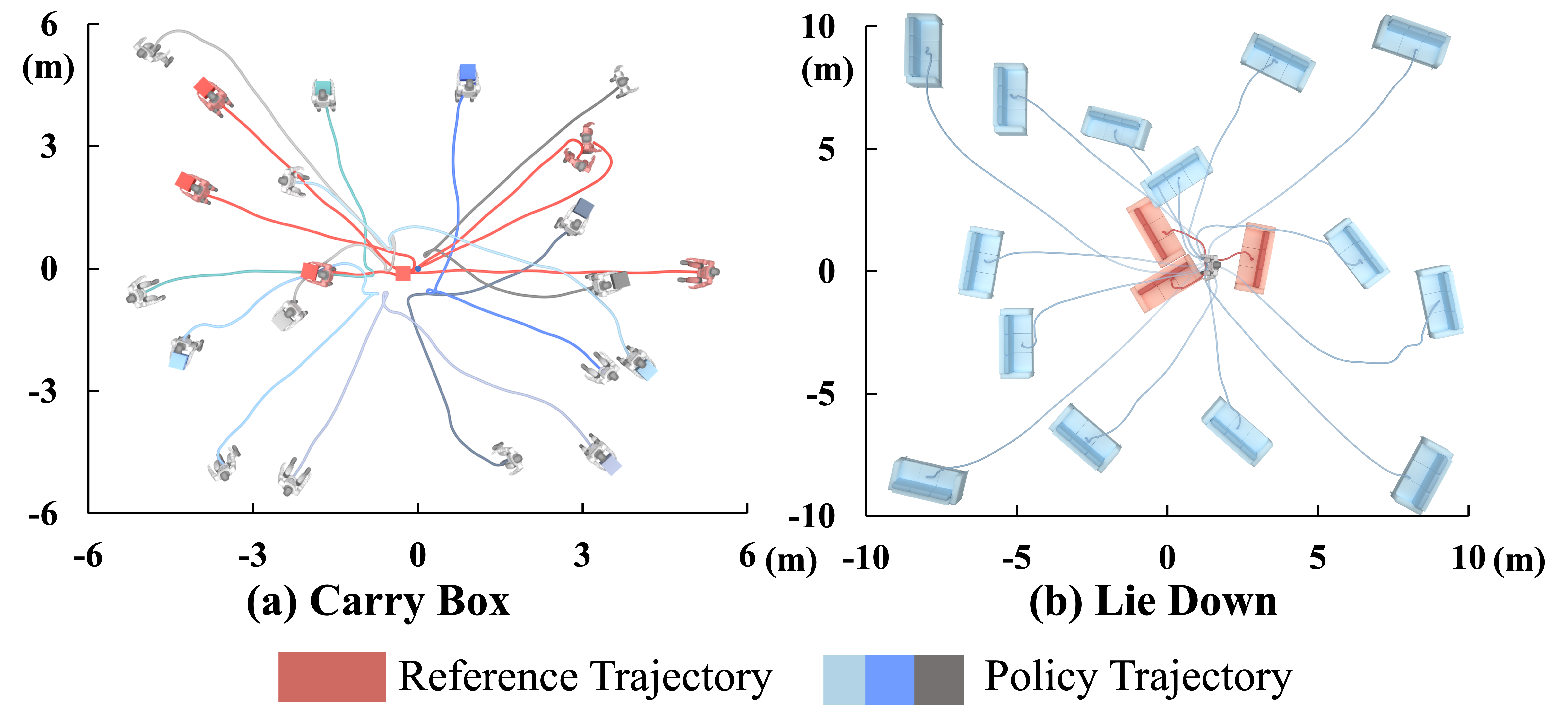

- Strong performance on long tasks: The robot successfully completed complex, multi-step tasks like carrying a box (walk → pick up → carry → place), as well as sitting, lying down, and standing up, both in simulation and in real life.

- Generalization to new scenes: Even when objects were placed in new positions, with different sizes and heights, the robot’s learned skills still worked well. It didn’t need to copy a fixed trajectory; instead, it learned a human-like “style” it could adapt to different scenarios.

- Natural, human-like motion: Movements looked smoother and more “human” compared to robots trained only with hand-crafted rewards. The AMP “judge” helped the robot learn realistic behavior.

- Reliable object localization: The coarse-to-fine perception worked as intended—rough guidance from far away and precise positioning up close. In tests, the error dropped from about 35 cm when far to around 5 cm when close.

- Outdoor demos and stylized walking: The system ran outdoors using only onboard sensors. It even learned fun, stylized locomotion like dinosaur-like walking or high-knee stepping, showing flexibility in movement style.

Implications: Why this research matters

This work is a step toward humanoid robots that can operate naturally in everyday places—homes, offices, outdoors—without needing special lab equipment. By combining human-style motion learning with robust, practical perception, PhySHSI shows that:

- Robots can learn general strategies (not just fixed scripts) for interacting with objects and scenes.

- Onboard sensors are enough for long, real tasks when you design a smart perception pipeline.

- Natural motion isn’t just for looks—it helps robots move more safely and predictably around people and furniture.

There are still challenges: stronger hands would handle bigger/heavier boxes, larger high-quality datasets would speed up learning, and more automated perception could reduce setup. But overall, this system brings us closer to helpful humanoid robots that can work smoothly in the real world.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed to be actionable for future research:

- Automated data generation at scale: The motion dataset relies on manual post-annotation (e.g., setting object pose to the midpoint of hands and aligning to the robot base), which is simplistic and labor-intensive. How to build large-scale, contact-consistent humanoid–object interaction datasets with automated, physics-consistent object trajectory inference and contact labels?

- Fiducial-free perception: Real-world deployment depends on AprilTags for fine localization and a manually specified coarse pose via LiDAR visualization. Can the system achieve robust, fiducial-free object detection and pose estimation (appearance-based RGB/RGB-D + LiDAR) across varied textures, occlusions, and lighting, indoors and outdoors?

- Active perception and search: The robot does not autonomously bring objects into view; failure can occur when coarse guidance never yields a tag in FOV. How to plan vantage points, perform active search, and reorient sensors to acquire objects reliably without manual initialization?

- Extrinsic calibration and synchronization: The paper does not describe calibration between LiDAR, camera(s), and the robot base nor time synchronization. What is the sensitivity of performance to calibration drift and latency, and how can online calibration or self-checks mitigate it?

- Odometry drift quantification: FAST-LIO drift is mentioned but not quantified over longer horizons or dynamic motions. What are drift characteristics outdoors and during aggressive whole-body motion, and how can loop closure or map-based correction improve coarse localization?

- Handling untagged, dynamic, and deformable objects: The approach assumes static chairs/beds and boxes with a simple grasp model. How to localize and manipulate untagged objects that move independently, have non-rigid geometry (e.g., bags, pillows), or require orientation control during transport?

- Grasp-state sensing and slip detection: After grasping, the system masks object pose and relies solely on proprioception. Can tactile/force sensing or gripper-mounted vision be integrated to detect slip, infer object inertia, and maintain stable grasps when the object leaves the camera FOV?

- Multi-object and cluttered scenes: The paper evaluates single-object tasks in relatively simple scenes. How does the system perform with multiple identical/different objects, clutter, partial occlusions, and dynamic obstacles (e.g., moving people, pets), and what fusion strategies are needed?

- Terrain and environment diversity: Real-world trials do not include uneven terrain, stairs, slopes, soft/low-friction surfaces, or adverse weather/lighting. What adaptations (perception, control, shoe/foot design) are required to maintain robustness on challenging terrains and conditions?

- Policy memory and hierarchy: The actor uses a short 5-step observation history, with no explicit recurrent memory or hierarchical decomposition. Would recurrent policies (e.g., LSTMs/Transformers) and learned stage/option policies improve long-horizon credit assignment, robustness, and interpretability?

- Style control and conditioning: Stylized locomotion is shown but not controllable at run time. How to parameterize and condition AMP policies on style tokens/embeddings for on-demand style modulation while preserving task success?

- Discriminator’s privileged inputs vs. deployment reality: The discriminator uses privileged object pose, but the actor faces masked/noisy observations at deployment. What is the performance impact of training the discriminator with realistic observation noise or partial observability, and can a consistency regularizer or adversarial domain randomization bridge this gap?

- Reward/style weighting schedule: The schedule for increasing style weight and the effect of L2C2 smoothness are not systematically studied. What are the trade-offs between naturalness and task success across different schedules and regularizers, and can adaptive scheduling improve stability?

- Comparative real-world baselines: Real-world performance is reported without comparison to model-based controllers, hierarchical visuomotor policies, or modern imitation/diffusion baselines. How does the system stack up empirically against strong baselines in success, precision, energy use, and recovery from perturbations?

- Human-likeness metric validity: Human-likeness is scored using an LLM (Gemini-2.5-Pro) without human raters or biomechanics metrics. How reliable is this metric, and can standardized, multi-rater human studies and kinematic/energetic measures offer more trustworthy assessments?

- Safety and failure handling: The system lacks explicit fall prevention, recovery behaviors, or safe fallback strategies under perception or actuation failures. What safe-stop, retreat, and recovery policies are needed for deployment in human-populated environments?

- Hardware generalization: Experiments are limited to Unitree G1 with a rubber hand. Does the approach transfer to other humanoid morphologies, hands (multi-fingered, suction), and sensors (stereo, event cameras), and what retraining/adaptation is needed?

- Energy, thermal, and wear considerations: The paper notes motor overheating risks with heavier boxes but does not quantify energy consumption or thermal limits under long tasks. How can policies be adapted to minimize energy/thermal stress, and what monitoring is required for safe operation?

- Object placement accuracy under occlusion: During placement, the object pose can be masked (e.g., leaving FOV). How can placement be made accurate under occlusion (e.g., through tactile feedback, wrist-mounted cameras, or learned object-state estimation from arm kinematics)?

- Generalization beyond four tasks: The system covers carry box, sit down, lie down, and stand up. How well does it extend to more diverse interactions (e.g., door opening, tool use, drawer/cabinet manipulation, stair traversal, push/pull tasks), and what data and perception changes are required?

- Scene understanding and planning: The approach is largely reactive without global path planning or semantic scene understanding. Can integrating mapping, obstacle avoidance, and semantic affordance detection (e.g., identifying sit-able surfaces) improve performance and autonomy?

- Domain randomization coverage: Domain randomization details (noise magnitudes, delays, masking triggers) are not fully specified or analyzed. What randomization regimes most improve sim-to-real transfer, and how can we quantify coverage vs. real-world failure modes?

- AMP variants and alternative imitation methods: The paper uses AMP but does not compare against modern alternatives (e.g., diffusion policies for control, adversarial IL variants, token-conditioned AMP). Which methods best balance realism, sample efficiency, and robustness for HSI?

- Style–task trade-offs: The catwalk-style locomotion inherited from AMASS may not be optimal for stability or energy. How does style choice affect task success, safety, and energy, and can multi-objective training explicitly trade off style vs. performance?

- Quantifying localization handoff: The coarse-to-fine transition is reported around ~2.4 m without systematic sensitivity analysis. How should transition thresholds adapt to object size, sensor FOV, motion speed, and odometry quality to minimize handoff failures?

- Robustness to sensor outages: AprilTag loss and system crashes caused failures, but resilience strategies are not explored. Can redundant sensing, confidence-aware control, and quick re-localization (e.g., brief scanning behaviors) reduce outage-induced failures?

- Dataset bias and realism: Reference motions include limited sequences (2–5 per task) and catwalk locomotion styles; object annotations are rule-based. How do these biases affect learned behaviors, and can more diverse, in-the-wild HSI datasets reduce style and interaction bias?

- Formal guarantees and verification: No stability or safety guarantees are provided for whole-body contact-rich interactions. Can formal verification or constraint-based controllers be combined with AMP policies to guarantee balance, collision safety, and joint-limit compliance?

Glossary

- 6D normal-tangent representation: A continuous 6D rotation encoding using two orthonormal 3D vectors to represent 3D orientation without singularities. "encoded with a 6D normal-tangent representation"

- Adversarial Motion Priors (AMP): An adversarial imitation framework where a discriminator encourages a policy to match motion styles from a reference dataset. "we then train generalizable HSI policies via reinforcement learning with adversarial motion priors (AMP)"

- AMASS: A large collection of human motion sequences parameterized by SMPL, used as motion priors. "from the AMASS dataset"

- AprilTag: A visual fiducial marker system for accurate, robust 6-DoF pose estimation from camera images. "For fine-grained localization at close range, AprilTag detection is employed to provide accurate object position"

- Asymmetric actor-critic: An RL setup where the actor (policy) and critic (value function) receive different observations, often giving the critic privileged information. "we adopt the asymmetric actor-critic framework"

- Discriminator: In adversarial learning, a classifier trained to distinguish real (dataset) motions from policy-generated motions, guiding style realism. "A discriminator distinguishes between policy-generated and reference motions to facilitate learning of natural behaviors and task completion."

- Domain randomization: Sim-to-real technique that randomizes simulation observations/dynamics to improve robustness in real deployment. "we apply domain randomization"

- End-effector: The terminal link(s) of a robot (e.g., hands, feet) that directly interact with the environment. "five end-effectors (left/right hand/foot, and head)"

- FAST-LIO: A real-time LiDAR-inertial odometry algorithm for accurate pose estimation by fusing LiDAR and IMU data. "we use FAST-LIO to estimate the odometry"

- Forward kinematics (FK): Computing the pose of robot links/end-effectors from joint angles and known kinematic parameters. "It is easy to get accurate by forward kinematics (FK) with joint encoder information."

- Gradient penalty: A regularization term that penalizes large discriminator gradients to stabilize adversarial training. "regularizes the gradient penalty"

- GVHMR: A video-based human motion reconstruction method that recovers SMPL motions from videos. "retargeted to SMPL motions using GVHMR"

- Humanoid-Scene Interaction (HSI): Whole-body humanoid behaviors involving interactions with objects and the environment (e.g., carry, sit, lie). "humanoid-scene interaction (HSI) system"

- IsaacGym: A GPU-accelerated physics simulation platform for scalable reinforcement learning. "All training and evaluation environments are implemented in IsaacGym"

- L2C2 smoothness regularization: A policy/action smoothness regularizer that reduces jerky motions for safer hardware deployment. "we adopt the L2C2 smoothness regularization"

- LiDAR-Inertial Odometry (LIO): Pose estimation that fuses LiDAR and inertial measurements to track robot motion. "LiDAR-Inertial Odometry (LIO)"

- Motion capture (MoCap): Sensor/camera-based systems that record precise 3D human or object motion for ground-truth trajectories. "Motion capture (MoCap) systems can provide accurate global information"

- PD controller: A proportional-derivative joint controller that tracks target joint positions by damping error and velocity. "executed by a PD controller across all 29 humanoid DoFs."

- Proprioception: A robot’s internal sensing (e.g., joint angles, velocities, base orientation/IMU) used for control. "a 5-step history of proprioception"

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): A policy-gradient RL algorithm using clipped objectives to stabilize training. "we use the proximal policy optimization (PPO) to maximize"

- Reference State Initialization (RSI): Initializing episodes from randomly sampled reference states to improve exploration of long-horizon tasks. "we adopt the reference state initialization (RSI) strategy"

- Retargeting: Mapping motion from a source body (human) to a target model (robot) while preserving semantics/feasibility. "retarget SMPL motions from the AMASS and SAMP datasets"

- SAMP: A dataset of human motions used alongside AMASS for training motion priors. "SAMP datasets"

- SE(3): The 3D rigid-body transformation group combining rotations and translations. "SE(3)"

- Sim-to-real transfer: Transferring policies trained in simulation to real robots while mitigating sensor and dynamics gaps. "leaving sim-to-real transfer an unexplored obstacle."

- SMPL: A parametric human body model (Skinned Multi-Person Linear model) used to represent and retarget human motions. "SMPL motions"

- Unitree G1: A commercial humanoid robot platform used for real-world experiments in this work. "Our system is built on the Unitree G1 humanoid robot,"

Practical Applications

Practical Applications Derived from the Paper

Below are actionable applications that leverage the paper’s findings and system components (AMP-based training pipeline, hybrid RSI, coarse-to-fine LiDAR+camera perception, asymmetric actor-critic training, motion smoothness regularization, and a deployable onboard stack). Each item is categorized and tied to relevant sectors, with tools/workflows and feasibility assumptions.

Immediate Applications

These can be piloted or deployed now in controlled environments using the released methods and a comparable hardware stack (e.g., Unitree G1 with LiDAR + RGB-D camera + onboard compute).

- Industry — Robotics R&D and Startups

- Use case: Rapid prototyping of humanoid-scene interactions (carry light boxes, sit/stand/lie) for customer demos, pilots, and showcases.

- Tools/workflows: AMP-based policy training with hybrid RSI in IsaacGym; coarse-to-fine object localization (FAST-LIO + AprilTag) ROS2 node; onboard deployment on Jetson Orin-class modules; L2C2 motion smoothing; stylized locomotion tuning for brand-specific motion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Tagged objects or goal zones for fine localization; manual coarse initialization via LiDAR visualization; payloads < ~3.6 kg and sizes ≤ ~45 cm; relatively flat terrain; safety operator present; controlled FOV and occlusion.

- Warehousing and Logistics (pilot-scale)

- Use case: Internal transport of small, tagged parcels between stations; carry-and-place into marked bins/shelves; “last-10-meters” movement in facilities.

- Tools/workflows: Coarse-to-fine localization with AprilTags on bins/racks; operator-in-the-loop to specify coarse goal in LiDAR view; scheduling via a fleet dashboard; domain-randomized policies to handle varied object sizes/heights (0–60 cm).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Fiducials (AprilTags) at pickup/placement; light payloads; moderate aisle clutter; low speed and safety clearance; reliable LiDAR odometry; periodic re-localization to limit drift.

- Healthcare/Hospitality (campus pilots)

- Use case: Delivery of light items to rooms; structured interactions with furniture (approach chairs/beds, sit/stand), concierge tasks with stylized walking for guest engagement.

- Tools/workflows: Tagged carts/chairs/beds for precise docking; pre-mapped corridors; onboard compute; stylized locomotion variants for user-facing presence; human-supervised operation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Non-clinical assistance (no patient transfer); hygiene protocols and corridor etiquette; facility-approved fiducials; battery swaps; staff oversight.

- Entertainment/Marketing/Events

- Use case: Live activations with natural or stylized humanoid motion (catwalk-style, dinosaur-like gait), seated segments, or lying-down routines in exhibition spaces.

- Tools/workflows: Rapid stylization training with AMP priors; scripted/choreographed sequences; onboard sensing only (portable); safe motion envelopes; show-control integration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Smooth flooring; predefined interaction zones; minimal heavy manipulation; safety marshals; rehearsal for camera/FOV conditions.

- Education and Academic Labs

- Use case: Teaching modules on reinforcement learning and sim-to-real for humanoids; reproducible assignments replicating four tasks (carry/sit/lie/stand).

- Tools/workflows: IsaacGym training setup; adversarial motion priors; hybrid RSI curriculum; ablation studies; evaluation with LLM-based human-likeness scores; example policies for Unitree G1.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to AMASS/SAMP motion datasets; GPU resources; university lab robots or high-fidelity simulation.

- Software Tooling (ROS2 ecosystem)

- Use case: Packaging the coarse-to-fine object localization into a reusable ROS2 component; dataset annotation tool that infers object trajectories from contact frames; evaluation scripts.

- Tools/workflows: FAST-LIO + AprilTag integration; FK-based frame management; policy deployment node; logging and automatic mode switching (coarse/fine).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Calibrated sensors; fiducials; synchronization (time stamps); open-source licensing and maintenance.

- Policy and Safety Pilots

- Use case: Define operating envelopes for early humanoid pilots—payloads, object sizes, heights, FOV limits, minimum safety distances, fiducial placement policy.

- Tools/workflows: Onsite risk assessments driven by the paper’s quantified ranges; facility signage and restricted areas; emergency stop protocols.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Alignment with local safety standards; insurer oversight; staff training; systematic trials with telemetry.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling, or additional components (e.g., dexterous hands, untagged perception, larger payloads, robust compliance).

- Warehousing/Manufacturing at Scale

- Use case: Autonomous pick–carry–place of diverse, untagged items; palletizing; shelf interaction; multi-step sequences with tight placement tolerances.

- Tools/workflows: Replace AprilTags with robust 6D pose estimation for open-set objects; active perception with viewpoint planning; dexterous, force-controlled grippers; AMP + diffusion policies for flexible interaction; digital-twin validation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable vision under clutter/occlusion; heavier-payload manipulators; compliance and safety certification; large-scale task data.

- Healthcare and Eldercare Assistance

- Use case: Activities of daily living—fetching items, safe sit-to-stand assistance, bed positioning, fall recovery; long-duration operation around people.

- Tools/workflows: Human-intent recognition; risk-aware policies; force/torque sensing and compliant control; privacy-preserving perception; clinical HRI protocols.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Rigorous clinical validation; ethical guidelines; legal approvals; very high reliability; soft end-effectors and redundancy in safety.

- Smart Homes and Consumer Robotics

- Use case: Household helper capable of fetching/placing light objects, setting tables, rearranging chairs, laundry bin transport, “natural” behaviors around furniture.

- Tools/workflows: Home anchors or SLAM map features instead of tags; language-guided tasking; personalization via in-home motion priors; low-power, on-device inference.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cost-effective platforms; robustness to home variability and clutter; simple user interfaces; maintenance and charging ecosystems.

- Construction and Facility Operations

- Use case: Transport of small materials, tool positioning, furniture manipulation (door/chair handling), energy-saving sit/stand routines during idle periods.

- Tools/workflows: Ruggedized hardware, dust/water-resistant sensors; outdoor SLAM; terrain-aware locomotion trained via AMP with rough-terrain priors; tool adapters.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Increased payload and reach; fall protection; regulatory compliance on active worksites.

- Public Safety and Disaster Response

- Use case: Search support in structured environments; supply delivery; low-profile locomotion/lying motions to traverse under obstacles; manipulation of doors/furniture.

- Tools/workflows: Tagless perception (thermal, radar, multispectral); remote-supervised autonomy; fault-tolerant controllers with safe failover.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Extreme reliability; communications resilience; mission-specific training; certification.

- Standardized HSI Benchmarks and Pretraining

- Use case: Community benchmarks and datasets for humanoid-scene interaction; generalist pretraining across many tasks with AMP-style objectives.

- Tools/workflows: Scalable collection and automatic annotation of HSI data (contact-based object inference, inverse dynamics filters); shared sim suites; LLM-based evaluators for motion naturalness.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Dataset licensing (AMASS/SAMP/video retargeting); compute budgets; shared metrics and consortium governance.

- Finance/Insurance and Risk Modeling

- Use case: Actuarial models for humanoid deployments in public/factory spaces using quantified operating ranges and failure modes; premium pricing based on telemetry.

- Tools/workflows: Simulation-based stress testing; standardized incident reporting; hazard maps derived from perception logs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to longitudinal field data; regulatory frameworks; privacy safeguards.

- Policy and Standards Development

- Use case: Technical standards for fiducial-assisted (and later fiducial-free) perception phases; certification protocols for AMP-trained control policies; labeling schemes for “robot-interactable” objects.

- Tools/workflows: Conformance tests; reference datasets and scenes; liaison with standards bodies (e.g., ISO/IEC).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Industry consensus; repeatable, cross-vendor validation procedures.

- Policy-as-a-Service and Customization Platforms

- Use case: Cloud service where customers upload motion capture/video data and scene specs to obtain customized HSI policies validated in a digital twin and packaged for their robot.

- Tools/workflows: Secure data ingestion; automated retargeting and object annotation; AMP-based multi-task training; sim-to-real checklists; on-device deployment toolchains.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Data governance and IP protection; scaling GPU infrastructure; cross-hardware compatibility bridges.

- Vendor-Agnostic Onboard Inference Stack

- Use case: Lightweight, energy-efficient control stack for multiple humanoid platforms using PD-tracked joint targets, AMP-style regularization, and L2C2 smoothing.

- Tools/workflows: Hardware abstraction layers; calibration utilities; standardized observation/action schemas; perception plug-ins (LiDAR, RGB-D).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Manufacturer APIs; synchronized timing; community-maintained drivers.

Notes on feasibility and constraints (cross-cutting):

- Current system is optimized for light payloads, moderate object sizes, and flat indoor/outdoor terrains with fiducials. Heavier manipulation and untagged objects require improved hands, sensing, and perception.

- Coarse-to-fine localization relies on accurate odometry and proper fiducial placement; eliminating tags implies robust multi-view 6D pose estimation and active perception.

- Manual coarse initialization can be removed with autonomous exploration policies and object search behaviors.

- Safety, regulatory approvals, and human factors will govern deployment pace in public/clinical environments.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.