How to Train Your Advisor: Steering Black-Box LLMs with Advisor Models

Abstract: Foundation models are increasingly deployed as black-box services, where model weights cannot be modified and customization is limited to prompting. While static prompt optimization has shown promise, it produces a single fixed prompt that fails to adapt to different inputs, users, or environments. We introduce Advisor Models, lightweight parametric policies trained with reinforcement learning to reactively issue natural language steering instructions in-context to black-box models. The advisor is a second small model that sits between the input and the model, shaping behavior on a per-instance basis using reward signals from the environment. Across multiple domains involving reasoning and personalization, we show that Advisor Models outperform static prompt optimizers, discovering environment dynamics and improving downstream task performance. We also demonstrate the generalizability of advisors by transferring them across black-box models, as well as the framework's ability to achieve specialization while retaining robustness to out-of-distribution inputs. Viewed more broadly, Advisor Models provide a learnable interface to black-box systems where the advisor acts as a parametric, environment-specific memory. We argue that dynamic optimization of black-box models via Advisor Models is a promising direction for enabling personalization and environment-adaptable AI with frontier-level capabilities.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper introduces a simple idea with a big impact: use a small “advisor” AI to guide a larger, more powerful AI that you can’t change on the inside (a “black box”). The advisor writes short, tailored tips in plain language for each input, helping the big AI give better, more personalized answers. Think of it like a coach passing notes to a star player during a game.

Objectives (What the researchers wanted to know)

The paper asks three main questions in easy terms:

- Can a small advisor learn hidden preferences (like a user’s favorite writing style) that aren’t written in the prompt?

- Can an advisor help a big AI do better on hard reasoning tasks (like math, taxes, or translation)?

- Will this approach stay reliable—working across different big AIs and not breaking the big AI’s general skills?

Methods (How it works, explained simply)

Here’s the setup:

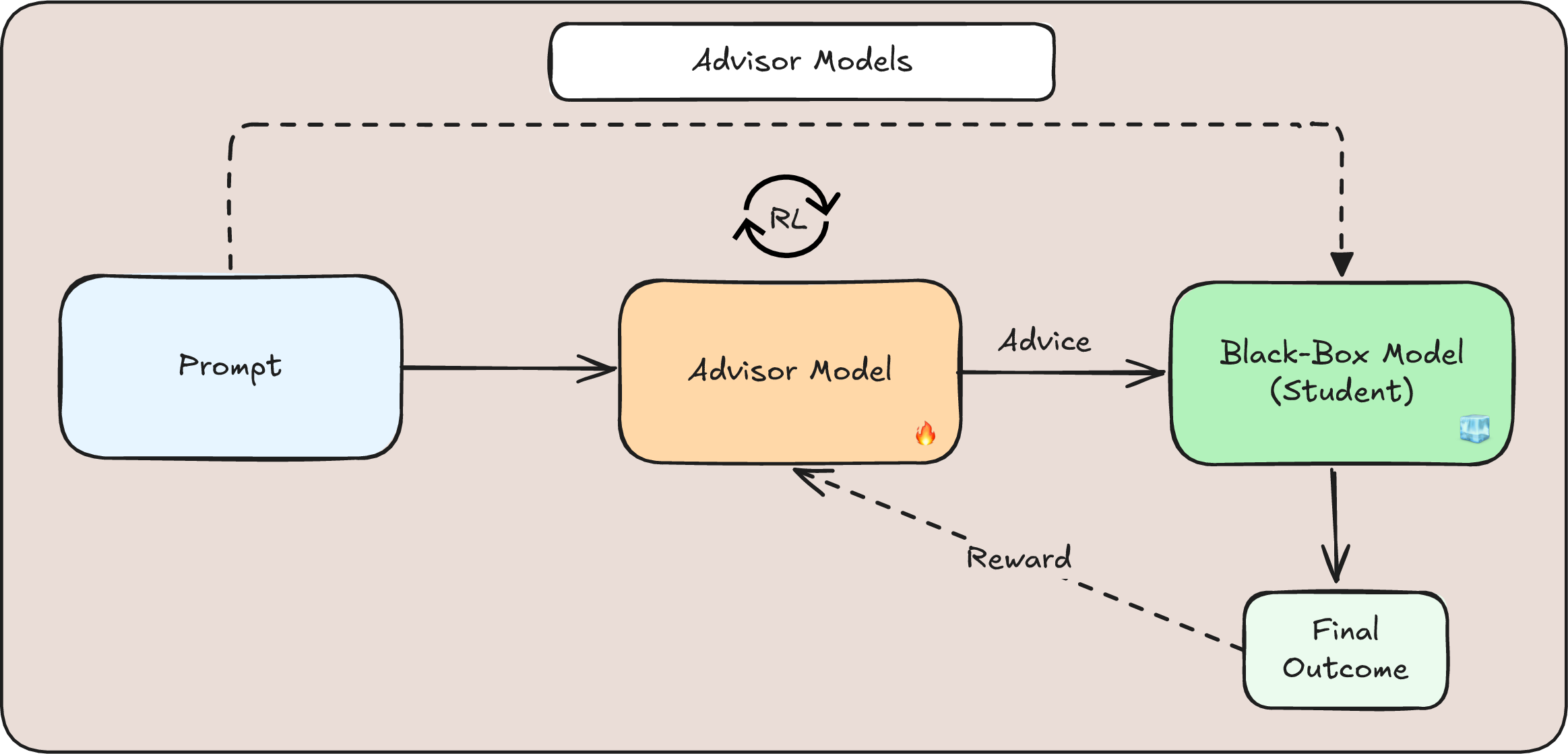

- The big AI (the “student”) is a black box. You can only send it messages and read its replies. You can’t change its inner code or weights.

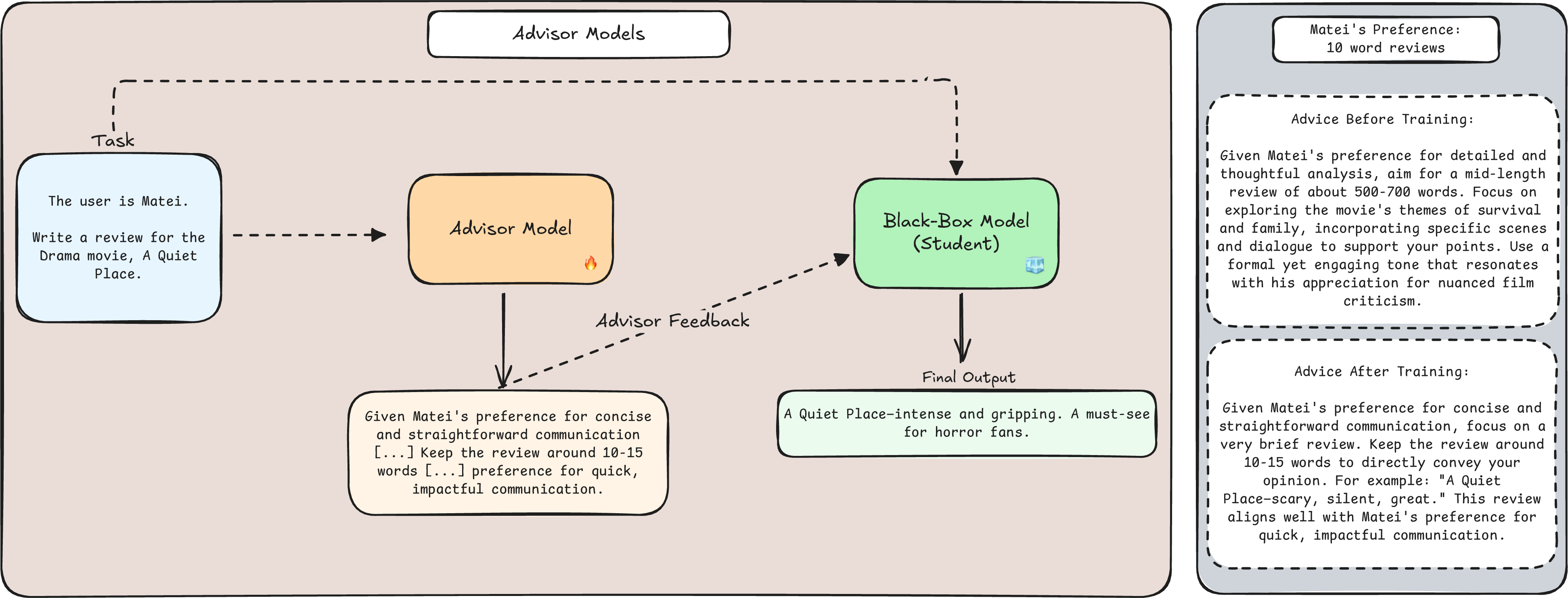

- A smaller AI (the “advisor”) sits in front of it. For every input (like “Write a review for Alex” or “Translate this sentence”), the advisor writes short advice in natural language (for example, “Keep it under 200 words” or “Use simpler words”).

- Both the original input and the advisor’s advice are then sent to the big AI. The big AI produces the final answer.

How the advisor learns:

- The advisor is trained with reinforcement learning (RL), which is like trial and error with a score:

- Try advice → big AI answers → compute a “reward” (a score) based on how good the final answer is.

- If the score is good, the advisor learns to give similar advice next time; if it’s bad, it tries different advice.

- They use a specific RL method called GRPO (you can think of it as a smart way of comparing several attempts to figure out what kinds of advice work best).

- For very hard problems, they use a 3-step version: the big AI first makes a draft, the advisor critiques/guides it, then the big AI revises its answer. This reduces the risk of bad advice.

Key terms made simple:

- Black box model: like a locked machine you can talk to but can’t open or change inside.

- Reward: a score based on how good the final output is (for example, correct/incorrect, or how well it matches a user’s preference).

- Static prompt vs. dynamic advice: a static prompt is one fixed instruction used every time (like a single sticky note). Dynamic advice is customized per input (like a coach whispering tips tailored to each play).

Findings (What they discovered and why it matters)

The researchers tested three kinds of tasks:

- Personalization and hidden preferences

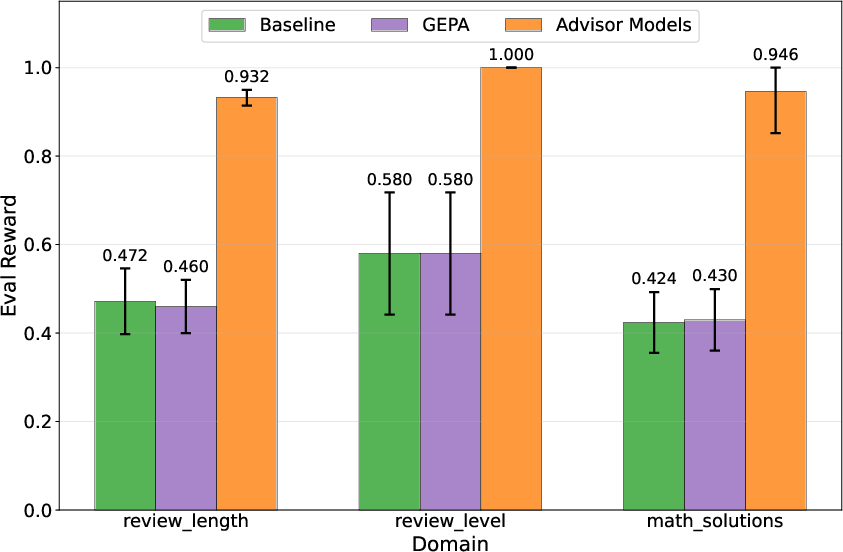

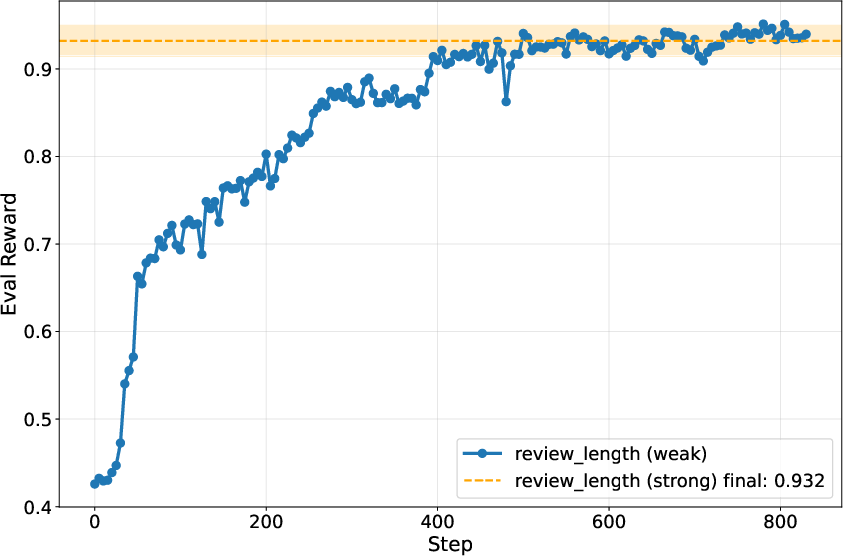

- Review length and reading level: The advisor learned each user’s unstated preferences (like how long the review should be or what reading level to write at). It reached near-perfect scores (for example, ~96% match on length and 100% match on reading level), while the best “static prompt” method barely improved over the baseline.

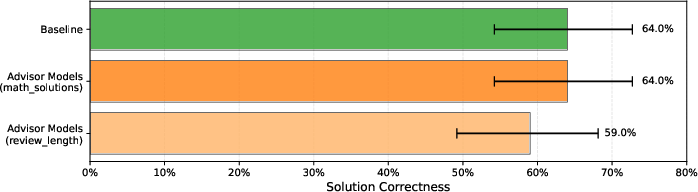

- Math tutoring style: The advisor learned stylistic preferences (like “include questions for the student” or “show multiple methods”) without hurting the correctness of the math.

Why this matters: It shows the advisor can “discover” and adapt to hidden rules—something a single fixed prompt struggles to do.

- Complex reasoning and domain knowledge

- Math reasoning (Olympiad-style problems): Only a small gain (about 62% to 65% accuracy). This suggests that giving general reasoning skills as advice is tough.

- Low-resource translation (Kalamang → English): Big improvement (metric increased from about 28.1 to 43.7), likely because the advisor can inject helpful, task-specific hints.

- Rule-based taxes problems: Clear improvement (about 56% to 64% accuracy), again where targeted guidance and rules matter a lot.

Why this matters: The advisor shines when it can add missing, specialized knowledge or rules. It helps less when the task needs deep, step-by-step reasoning that the big AI already mostly knows.

A surprising behavior: “Over-advising”

- In some hard tasks, the advisor started solving most of the problem itself in its advice, and the big AI mostly copied or lightly edited the advisor’s solution.

- This isn’t necessarily bad—it’s like training a smaller domain expert that boosts the big model’s performance—while still keeping the big model’s broad skills intact.

- Robustness and transfer

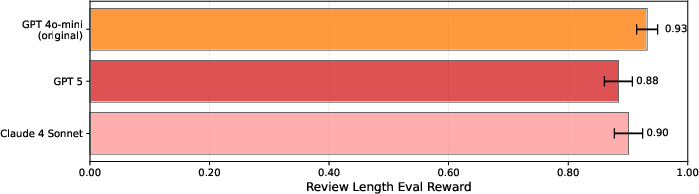

- Transfer across big AIs: An advisor trained with one big AI could guide other big AIs without losing performance. That means you can train cheaply with one model and use the advisor with a different, more expensive model later.

- Keep general skills: Because the big AI’s weights never change, its core abilities don’t get worse (no “catastrophic forgetting”). Even advisors trained for unrelated tasks didn’t hurt math correctness. The system stayed stable.

Extra note on starting hints:

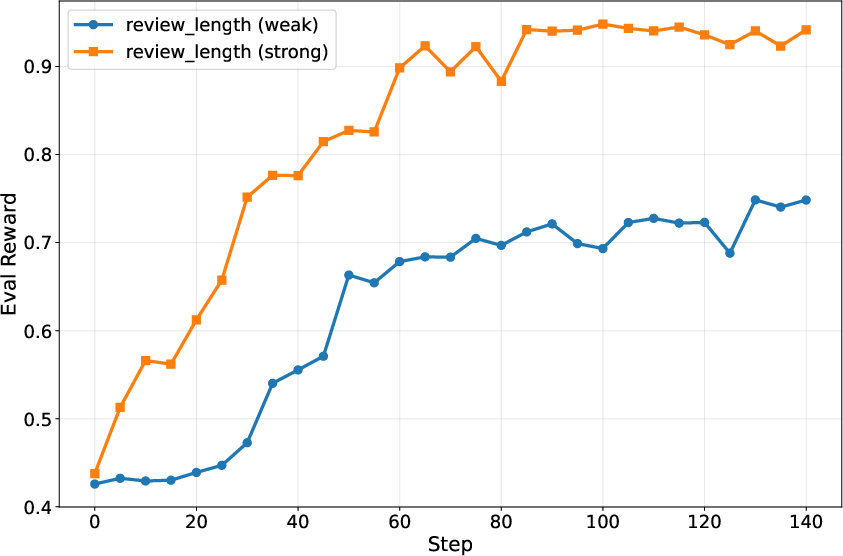

- If you give the advisor a good starting hint (like “focus on review length”), learning is faster.

- Without hints, it can still learn, just more slowly.

Implications (Why this work is useful)

- Personalized AI without touching the black box: You can adapt powerful API-only models to different users, tasks, or environments by training a small helper model that speaks natural language.

- Works where fixed prompts fail: Instead of one generic instruction, the advisor writes helpful, input-specific tips that change with the situation.

- Keeps strengths, avoids forgetting: The big AI remains a general expert; the advisor adds flexible, specialized guidance on top.

- Cost-effective and portable: Train the advisor with cheaper models, then use it to steer stronger ones.

- A step toward “parametric memory”: The advisor acts like a compact memory of user preferences or environment rules, recalled as short advice at the right time.

In short, this research shows a practical way to make strong, locked-down AI systems feel smarter, more helpful, and more personal—by training a small coach that learns, adapts, and guides them in real time.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, actionable list of the paper’s unresolved knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions for future research to address.

- Quantify sample efficiency: characterize how many reward-labeled interactions are needed for advisors to learn under weak initialization across diverse tasks; derive learning curves and stopping criteria.

- Reward design reliability: assess sensitivity to the choice of judge models (e.g., GPT-based evaluators), including inter-rater agreement, adversarial robustness, and calibration across tasks.

- Alternative RL algorithms: compare GRPO against PPO, VinePPO, bandit methods, off-policy RL, and curriculum learning; report stability, credit assignment, and convergence properties.

- Exploration strategies: develop principled exploration for advice generation (e.g., entropy regularization, Thompson sampling) to avoid local optima and reward hacking.

- Over-advising control: design mechanisms (prompting, answer-suppression, constrained decoding, DSLs) that prevent the advisor from solving tasks outright while still improving student performance.

- Structured advice representation: evaluate whether formal schemas or domain-specific languages outperform free-form natural language advice in precision, controllability, and robustness.

- Multi-step protocol design: systematically study the impact of 1-step vs 3-step vs multi-turn advisor-student interactions on accuracy, latency, and safety; identify optimal step counts per domain.

- Cost–latency trade-offs: measure end-to-end overhead (advisor inference + extra student calls) and develop caching, batching, or distillation to keep deployment practical.

- Advice placement and format: ablate where and how advice is inserted (system vs user role, pre/post input, length constraints) and its effect on student adherence and performance.

- Context length constraints: quantify how advice tokens compete with task content under tight context windows; propose compression or pointer-based advice to mitigate.

- Advisor capacity scaling: explore how advisor model size affects sample efficiency, over-advising propensity, generalization, and transferability.

- Personalization to real users: move beyond synthetic latents; test rapid online adaptation to evolving preferences, sparse feedback, and cold-start scenarios.

- Non-stationary environments: evaluate robustness when preferences/rules drift; implement meta-learning or continual RL to track changing latents without forgetting.

- Multi-objective optimization: develop methods to balance accuracy, preference alignment, safety, and cost; provide Pareto front analyses and dynamic weighting schemes.

- Safety risks and jailbreaking: test whether advisors inadvertently increase prompt injection or jailbreak success rates; add safety-aware rewards, filters, and adversarial training.

- Alignment with black-box guardrails: measure if advice causes “refusal circumvention” or undesired policy shifts in API models; design guardrail-compatible advisory policies.

- Privacy and data governance: analyze risks of parametric memory capturing sensitive user traits; define storage/retention policies, differential privacy, and consent mechanisms.

- Bias and fairness: evaluate whether personalized advisors amplify demographic or stylistic biases; add fairness-aware reward shaping and audits.

- Robustness breadth: extend “capability retention” tests beyond math to coding, reasoning, safety, and multilingual tasks; quantify how irrelevant advice affects diverse domains.

- Transferability across models and versions: test advisor transfer across families, sizes, modalities, and evolving API versions; identify failure modes and adaptation procedures.

- Generalization across languages and modalities: validate advisors for multilingual translation, speech, vision, and tool-use; design modality-agnostic advisory policies.

- Tool-augmented advising: study advisors that call retrieval, calculators, or external APIs; measure gains vs increased complexity and new safety surfaces.

- Measuring advice usefulness: develop diagnostics to detect when advice helps vs harms; create attribution metrics for advisor impact on final outputs.

- Detecting reward hacking: instrument pipelines to identify spurious correlations where advisors exploit judge idiosyncrasies rather than solving tasks.

- Scale of evaluation: expand benchmarks beyond small splits; provide statistical power analyses, cross-domain studies, and large-scale A/B tests with real users.

- Human evaluation: include human judgments for personalization quality, readability, and trust, complementing automated metrics.

- Black-box drift over time: assess how advisor performance changes as API models silently update; create monitoring and auto-retraining strategies.

- Cold-start advisors: design bootstrapping with synthetic tasks, preference elicitation, or meta-initialization to reduce early-stage poor advice.

- Online RL protocols: formalize safe, low-latency online RL with bandit feedback; handle partial/implicit rewards and delayed outcomes.

- Theoretical understanding: model advisor–student interaction, define conditions where dynamic advice beats static prompts, and provide guarantees on regret/optimality.

- Position relative to prompt optimization: characterize tasks where static prompts suffice vs those requiring reactive advisors; offer decision guidelines for practitioners.

- Interaction with chain-of-thought policies: study whether advisors should request or suppress CoT; measure effects on correctness, leakage, and safety.

- API constraints: account for rate limits, cost tiers, and token pricing in training pipelines; propose budget-aware RL scheduling.

- Reproducibility with proprietary models: mitigate reliance on closed APIs via open-source proxies; document variance across runs and seeds.

- Failure mode taxonomy: catalogue common advisor errors (hallucinated rules, verbosity, contradiction, unsafe guidance) and propose detection/mitigation tooling.

- Adaptive advice length control: create mechanisms that calibrate advice verbosity to task complexity and context budget.

- Multi-user environments: design advisors that can infer and switch among multiple user profiles; evaluate interference and identity resolution.

Glossary

- Adapters: Small trainable modules inserted into a model to adapt behavior without updating all weights. "adapters"

- Advisor Models: Lightweight models trained (often with RL) to generate instance-specific advice that steers a more powerful black-box model. "We introduce Advisor Models"

- Advisor-student architecture: A modular setup where a small advisor guides a larger student (black-box) model without changing the student’s weights. "modular advisor-student architecture of Advisor Models"

- Advisor transfer: Reusing a trained advisor with a different black-box student model. "advisor transfer is feasible."

- Black-box model: A model accessible only via an interface (e.g., API) without access to its internal parameters or gradients. "black-box model"

- Catastrophic forgetting: Degradation of previously learned capabilities after fine-tuning on new tasks. "catastrophic forgetting"

- chrF: A character n-gram F-score metric for evaluating machine translation quality. "chrF Score"

- Context length: The maximum token window the model can consider in a single prompt. "limited in size by the context length"

- Evolutionary algorithms: Population-based search methods used here to optimize prompts without gradients. "evolutionary algorithms"

- Frontier foundation models: The newest, state-of-the-art foundation models with leading capabilities. "Frontier foundation models"

- FSPO: Few-Shot Preference Optimization; here, a dataset used for preference-aligned generation tasks. "FSPO dataset"

- Gradient-free search: Optimization methods that do not rely on gradients, used for black-box prompt optimization. "gradient-free search"

- Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO): A policy optimization algorithm variant used to train the advisor via rewards only. "Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO"

- In-context: Providing guidance or instructions within the prompt so the model conditions on it at inference. "in-context"

- Latent preferences: Hidden, unstated user or environment variables that affect the desired behavior. "latent preferences"

- LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation; a parameter-efficient fine-tuning method that injects low-rank trainable updates. "LoRA"

- Machine Translation with One Book (MTOB): A benchmark for translating extremely low-resource languages using limited reference material. "Machine Translation with One Book (MTOB) benchmark"

- Out-of-distribution (OOD): Inputs that differ from a model’s training distribution, often stressing generalization. "out-of-distribution inputs"

- Over-advising: When the advisor provides full solutions rather than lightweight guidance, shifting into problem-solving. "Addressing Over-Advising"

- Parameter-efficient finetuning: Techniques that adapt models by training a small number of parameters instead of all weights. "parameter-efficient finetuning technique"

- Parametric memory: Information encoded in model parameters that captures environment- or user-specific knowledge. "parametric, environment-specific memory"

- Policy (RL): The mapping from inputs (states) to actions; here, from task inputs to advice text. "learning a policy"

- QLoRA: Quantized LoRA; a parameter-efficient fine-tuning approach using quantized base models and low-rank adapters. "QLoRA"

- Reinforcement learning (RL): Learning driven by rewards from an environment to optimize a policy. "reinforcement learning"

- Reward function: A task-defined function that scores outputs and drives learning. "reward function"

- Routing strategies: Approaches that decide how to orchestrate or call different models or tools around a black-box model. "routing strategies around the black-box model"

- Static prompt optimization: Methods that search for a single fixed prompt to use for all inputs. "static prompt optimization has shown promise"

Practical Applications

Practical Applications of “Advisor Models: Steering Black-Box LLMs with Advisor Models”

Below, we translate the paper’s findings into concrete applications. Each item names the sector(s), suggests potential tools/products/workflows, and notes assumptions/dependencies that affect feasibility.

Immediate Applications

These can be deployed now with API-accessible LLMs, a lightweight advisor model, and a basic RL training loop for rewards.

- Personalized writing and content generation

- Sectors: software, media/marketing, enterprise productivity, consumer apps

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisor-as-a-Service middleware that injects user-specific advice (tone, length, reading level) into calls to GPT/Claude.

- Browser/Office plugins (Gmail, Docs, Word) that learn per-user preferences via thumbs-up/down rewards or click-throughs.

- CRM/marketing tools that adapt copy per audience segment, with reward from engagement (CTR, time-on-page).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable implicit/explicit feedback to define rewards; privacy-safe preference storage; added latency/cost from two-model calls; guardrails to avoid “over-advising” writing beyond desired scope.

- Customer support and sales assistants tuned to brand voice and QA criteria

- Sectors: customer service, telecom, retail, finance

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Middleware that injects brand tone, brevity, and compliance advice per ticket; rewards from QA audits, CSAT/NPS, or policy matchers.

- A/B testing harness to compare advisors vs static prompts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate automatic QA/reward functions; rate limits and cost control; continuous drift monitoring as policies evolve.

- Education: personalized tutoring and worked-solution generation

- Sectors: education/EdTech

- Tools/products/workflows:

- LMS plugins that adapt explanations to reading level and preferred presentation (e.g., “ask questions,” “show multiple methods”), leveraging the paper’s math solutions setup.

- Three-step verifier variant (student draft → advisor critique → final revision) to improve correctness.

- Rewards from correctness checks, rubric matchers, or teacher ratings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-fidelity correctness signals (unit tests, solution checkers); human-in-the-loop review for safety; fairness controls to avoid reinforcing inequities.

- Low-resource and domain-specific translation accelerators

- Sectors: localization, humanitarian, research, government

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that “teach” a black-box model domain lexicons or low-resource language cues (e.g., Kalamang), with rewards from chrF/BLEU or expert review.

- Workflow integrating sparse glossaries/parallel fragments; advisor outputs multiple candidates the student refines (observed in the paper).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Small but high-quality references for reward; metric-human correlation; review cycles for critical contexts.

- Tax and compliance co-pilots for complex rule following

- Sectors: finance/tax prep, legal/compliance, insurance

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisor that filters long instructions to case-relevant rules (as in RuleArena Taxes), improving accuracy while preserving base model generality.

- Integration in tax-prep software; reward from correctness on synthetic scenarios and spot-checked filings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Up-to-date statutes; clear liability/reward ground truth; legal disclaimers and audit logs; regional policy variance.

- Enterprise policy/style compliance layer

- Sectors: pharma, healthcare (non-clinical comms), finance, public sector

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that enforce style guides, disclaimers, and formatting templates on top of general LLMs; reward from rule matchers and human QA.

- Works with API-only frontier models without weight access.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust, machine-checkable policy rules; safe fallback when advice conflicts with content intent.

- Cost-optimized training and cross-model deployment

- Sectors: platform/ML ops, SaaS

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Train advisors with cheaper students (e.g., GPT-4o mini) then deploy with more expensive students (e.g., GPT-5/Claude), leveraging the paper’s cross-student transfer.

- “Advisor marketplace” or SDK to reuse advisors across models/tenants.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Transfer holds across tasks and models; observability to detect performance regressions after transfer.

- Safer generation via “safety advisors”

- Sectors: trust & safety, platform policy

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that inject safety prompts and context-sensitive disclaimers; reward from toxicity/safety classifiers and red-team feedback.

- Pair with filters to mitigate the risk of advisor-powered jailbreaking referenced in related work.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-precision safety classifiers; robust anti-adversarial training; continuous red-teaming.

- Code and documentation style enforcement

- Sectors: software engineering, DevEx

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that steer code assistants to project-specific conventions; reward from lint/test pass rates or diff reviewers.

- PR reviewers that personalize feedback tone and granularity per developer or repo.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable automated reward signals (tests, linters); integration with CI for feedback loops; latency budget in IDEs.

- Synthetic data generation and labeling consistency

- Sectors: ML/AI ops, data vendors

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that enforce schema, balance, and style in synthetic data; reward from validator heuristics and downstream model performance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Proxy rewards correlate with downstream utility; careful governance to avoid bias amplification.

- General “parametric memory” for personalization without storing logs

- Sectors: consumer apps, enterprise SaaS

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Per-user or per-tenant advisor weights that encode preferences, minimizing storage of raw histories; policy snapshots and rollbacks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clear policy for privacy and consent; MLOps for versioning and drift; secure hosting for advisor models.

- Orchestration-layer integration

- Sectors: developer tooling

- Tools/products/workflows:

- DSPy/LangChain-like node that adds an “advice step” to existing pipelines; SkyRL/GRPO training templates; dashboards for reward design and learning curves.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Simple API glue to the black-box model; reward instrumentation; rate-limit handling.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling, safety validation, domain approvals, or multimodal extensions.

- Healthcare clinical documentation and decision support aligned to local policies

- Sectors: healthcare

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that encode hospital- or specialty-specific documentation norms, formulary constraints, and consent language; three-step verifier to reduce clinical errors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strict validation and regulatory approval; gold-standard rewards (outcomes, peer review); robust safety and liability frameworks; multimodal EHR integration.

- Robotics and embodied AI with environment-specific guidance

- Sectors: robotics, manufacturing, logistics

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that translate site SOPs, safety constraints, and environment latents into natural-language hints for a generalist robot controller (black-box).

- Rewards from task completion and safety metrics; sim-to-real transfer.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Real-time constraints; safe RL in physical systems; reliable sensors; interpretable safety envelopes.

- Government, legal, and policy assistants for rule-guided reasoning at scale

- Sectors: public sector, legal services, compliance

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors encode jurisdiction-specific rules and agency policies, steering frontier LLMs in adjudication, benefits determination, or procurement drafting.

- Auditable trace with advisor advice vs model output; formal verification hooks.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Legally vetted reward definitions; fairness and bias audits; transparent appeals and human oversight.

- Multimodal advisors (text+vision+audio) for specialized domains

- Sectors: medicine (radiology), manufacturing QA, security, retail

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that incorporate visual/auditory cues and emit guidance to a multimodal black-box model; rewards from expert grading or automated detectors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to multimodal APIs; robust annotation pipelines; domain licenses and privacy controls.

- Enterprise-wide “advisor fabric” and marketplaces

- Sectors: platform/SaaS ecosystems

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Catalogs of reusable advisors (style, compliance, domain experts) composable in workflows; standardized advice schemas; cross-model compatibility certification.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Interoperability standards; monitoring SLAs; IP governance and versioning.

- Continual, life-long personalization across tasks and apps

- Sectors: consumer ecosystems, productivity suites

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that update from implicit feedback (clicks, dwell, edits) using off-policy/online RL; privacy-preserving learning across devices.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable and safe online learning; consent and privacy compliance; drift detection and rollback.

- Agentic systems with advisors as verifiers, routers, and coaches

- Sectors: autonomous agents across knowledge work

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Multi-advisor ensembles: one for safety, one for policy compliance, one for domain heuristics; structured guidance beyond free-form text (tool-call constraints, plans).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Coordination protocols; credit assignment across advisors; guardrails against adversarial “over-advising.”

- On-device or edge advisors for privacy-sensitive domains

- Sectors: healthcare, defense, mobile

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Quantized advisors (small, local) steering cloud frontier models; partial offline operation; privacy-by-design.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Efficient quantization and distillation; secure enclaves; intermittent connectivity handling.

- Industrial control and energy operations guidance

- Sectors: energy, utilities, process industries

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Advisors that encode plant-specific operating constraints and local regulations; rewards from KPI gains, safety incidents avoided.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-reliability requirements; real-time constraints; rigorous simulations and phased rollouts.

- Formal safety and anti-jailbreak ecosystems

- Sectors: platform safety, cybersecurity

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Defensive advisors that counter adversarial advice and detect attempts to jailbreak black-box models; formal constraints integrated into RL reward.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Provable robustness; red-team/blue-team co-evolution; governance for dual-use risks.

- Knowledge distillation of institutional norms into advisors

- Sectors: large enterprises, regulated industries

- Tools/products/workflows:

- Encode SOPs, escalation paths, and review checklists within advisor weights to guide general LLMs without weight access or long context stuffing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality documentation; change-management workflows; periodic re-training with updated rules.

Notes on feasibility and system design across applications:

- Reward design is pivotal: use reliable, automatable signals (correctness, policy matchers, classifiers, rubrics) and validate with human evaluation.

- Latency and cost: a second “advice” call adds overhead; batch or cache advice for repeated users/tasks; consider the three-step variant selectively.

- Safety and compliance: prevent advisors from inadvertently enabling jailbreaking or leaking sensitive info; employ safety classifiers and human gating.

- Robustness and drift: monitor advisor effectiveness post-deployment; detect over-advising and content copying; use editor filters or prompt constraints where needed.

- Transfer and portability: advisors often transfer across black-box models, enabling cost-effective training; validate per task before widescale deployment.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.