Secrets of the Brain: An Introduction to the Brain Anatomical Structure and Biological Function

Abstract: In this paper, we will provide an introduction to the brain structure and function. Brain is an astonishing living organ inside our heads, weighing about 1.5kg, consisting of billions of tiny cells. The brain enables us to sense the world around us (to touch, to smell, to see and to hear, etc.), to think and to respond to the world as well. The main obstacles that prevent us from creating a machine which can behavior like real-world creatures are due to our limited knowledge about the brain in both its structure and its function. In this paper, we will focus introducing the brain anatomical structure and biological function, as well as its surrounding sensory systems. Many of the materials used in this paper are from wikipedia and several other neuroscience introductory articles, which will be properly cited in this article. This is the first of the three tutorial articles about the brain (the other two are [26] and [27]). In the follow-up two articles, we will further introduce the low-level composition basis structures (e.g., neuron, synapse and action potential) and the high-level cognitive functions (e.g., consciousness, attention, learning and memory) of the brain, respectively.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What this paper is about

This paper is a beginner-friendly tour of the brain. It explains how the brain is built (its anatomy) and what its parts do (its functions), from simple animals to humans. It also introduces the body’s senses (like sight and hearing) and how they send information to the brain. This is Part 1 of a three-part tutorial: later parts cover how brain cells work (neurons, synapses) and higher mental skills (like attention and memory).

Key questions the paper answers

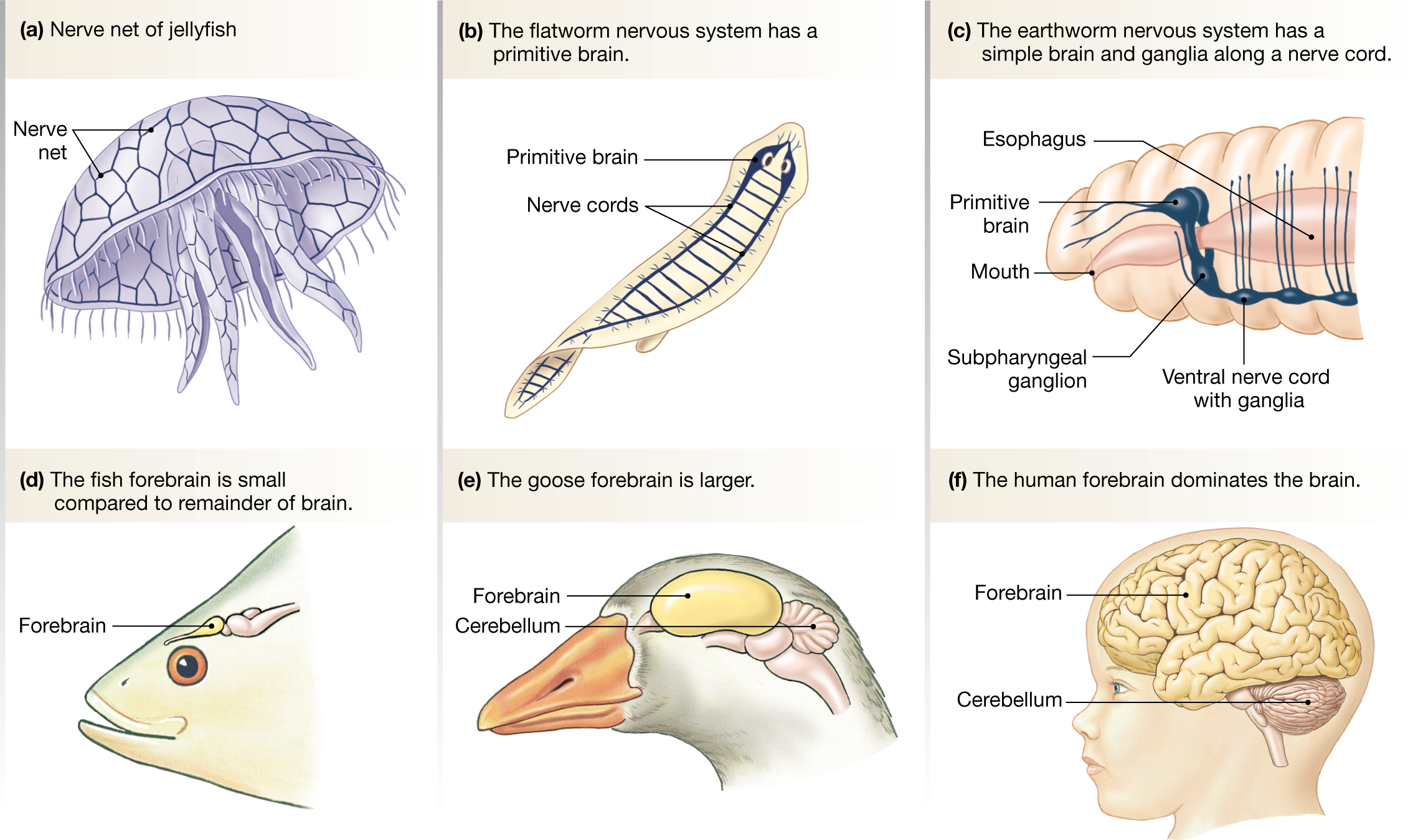

- How are animal nervous systems organized, and how do they compare?

- What are the main parts of the human brain, where are they, and what do they do?

- How is the wrinkly outer layer (the cerebral cortex) divided into functional areas and “Brodmann areas”?

- How do our senses work together with the brain to let us see, hear, feel, taste, smell, and keep balance?

How the paper explains things (the approach)

Instead of running new experiments, the author gathers trusted information (e.g., from neuroscience references and Wikipedia) and organizes it clearly. The paper:

- Starts with the big picture (nervous systems across animals) and zooms in to the human brain.

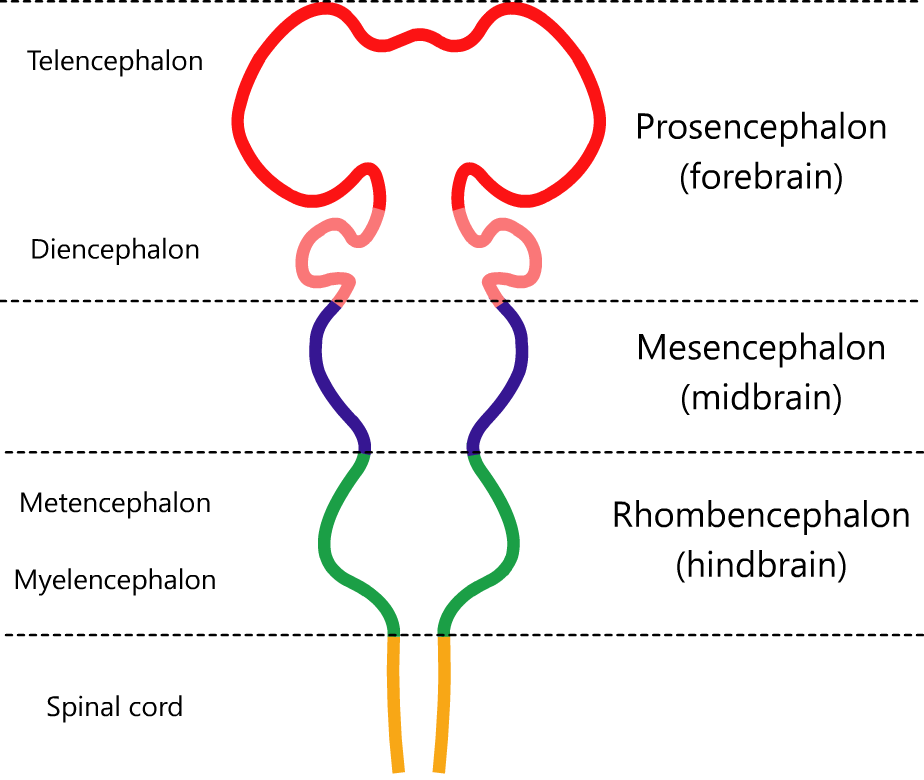

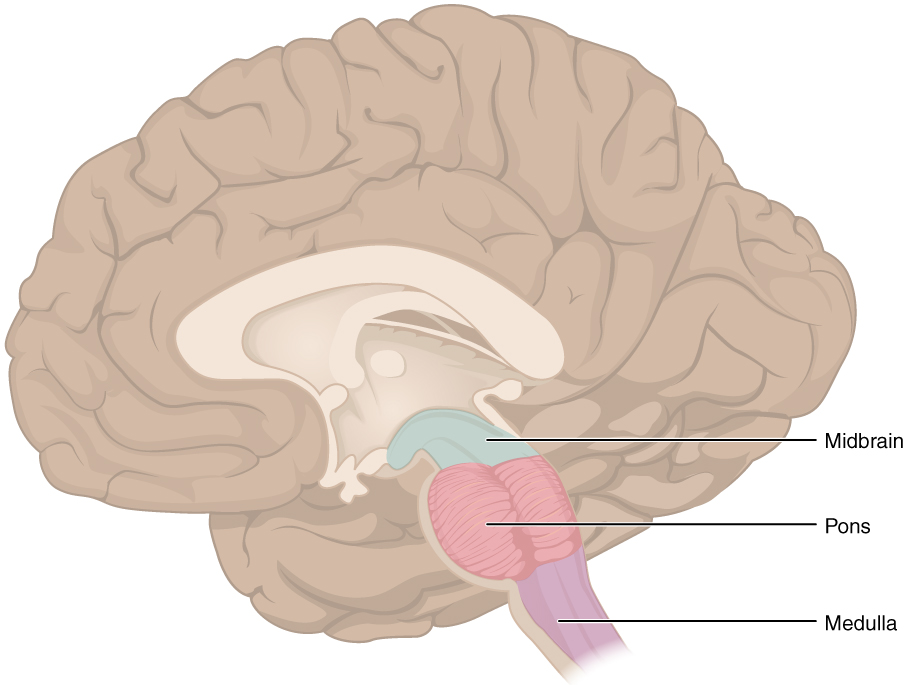

- Uses the standard anatomy “map” (brainstem, cerebellum, diencephalon, cerebrum).

- Adds helpful analogies, simple definitions, and diagrams (like maps of brain regions and sensory pathways).

Think of it like a field guide to the brain: it labels the “neighborhoods,” tells you what happens there, and shows how messages travel.

Main takeaways: what we learn

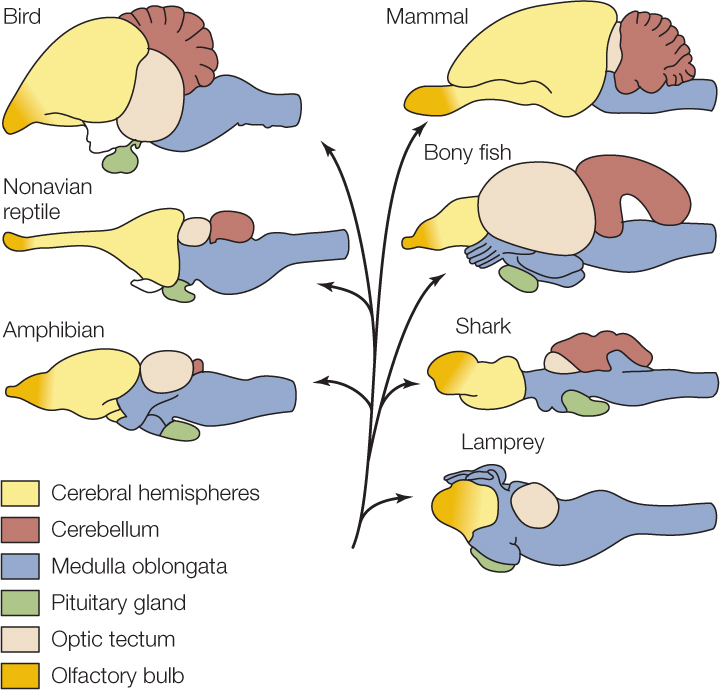

1) Nervous systems across animals share a common language

All animals use signals along nerve cells (neurons): electrical spikes (action potentials) and chemical messages across tiny gaps (synapses). What changes across species is the number of neurons and how they’re organized. As animals evolved, the front of the brain (especially the cerebrum) grew a lot in birds and mammals, and even more in primates and dolphins. Bigger and better-organized brains support more complex thinking.

Simple analogy: every animal uses the same “electrical wiring,” but some have a small toolkit, while others have a giant control center with many specialized rooms.

2) The human brain’s main parts and their jobs

- Brainstem: the body’s life-support autopilot. It manages heartbeat, breathing, sleep, and basic reflexes. It also relays information to and from the face and neck.

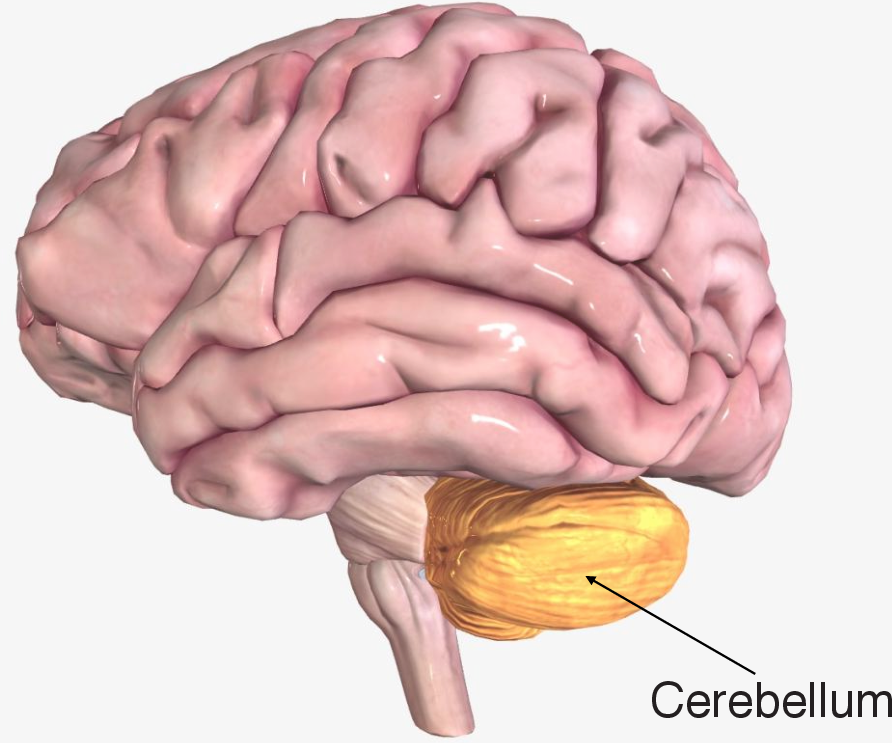

- Cerebellum: the brain’s coach and timekeeper. It fine-tunes movements so they’re smooth and accurate, and helps with motor learning (like getting better at riding a bike).

- Diencephalon:

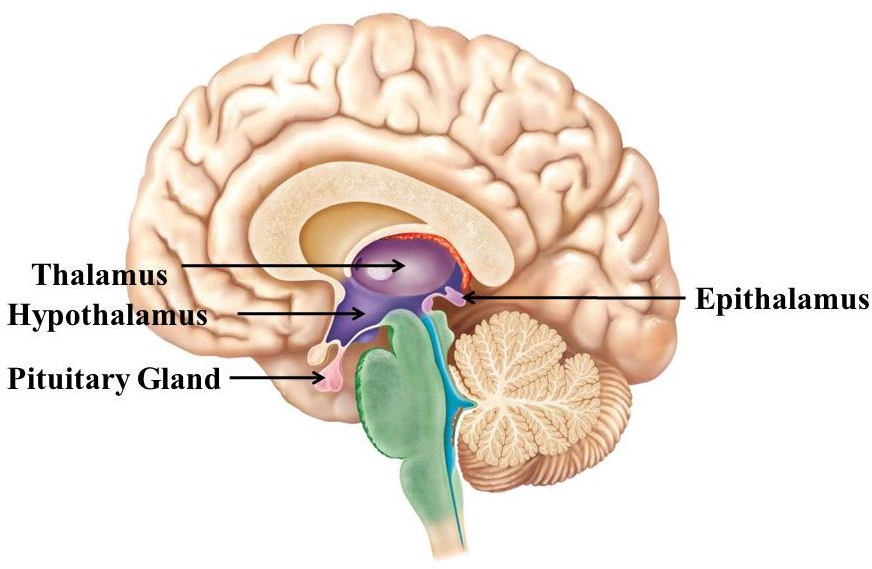

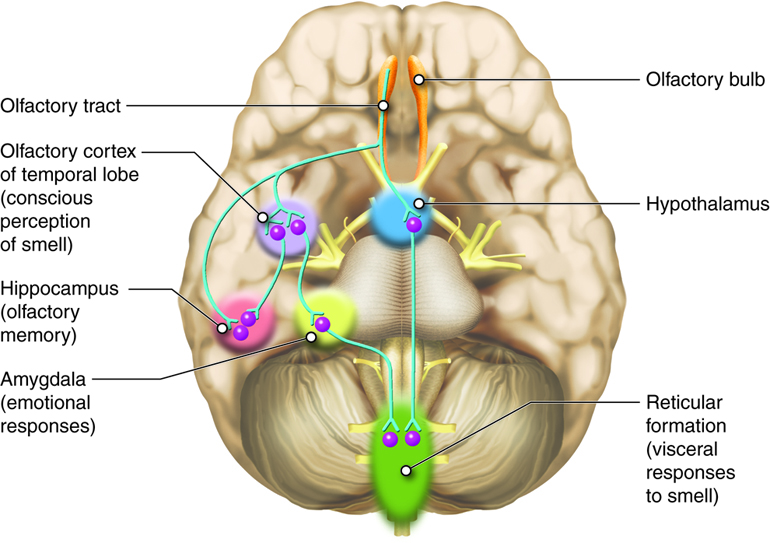

- Thalamus: the brain’s relay hub. Most sensory information (except smell) stops here before going to the cortex for detailed processing.

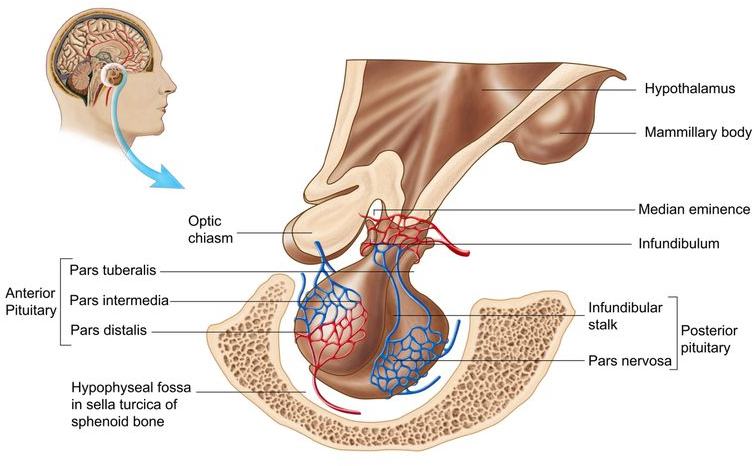

- Hypothalamus: the body’s thermostat and hormone manager. It helps keep internal balance (temperature, hunger, stress) and controls the pituitary gland.

- Pituitary gland: the “master gland” that releases hormones affecting growth, water balance, and more.

- Epithalamus and subthalamus: involved in sleep rhythms, mood, and movement control.

- Cerebrum: the largest, wrinkly top part. It handles thinking, memory, language, feelings, and voluntary movement. The two halves (hemispheres) talk through a large fiber bridge called the corpus callosum.

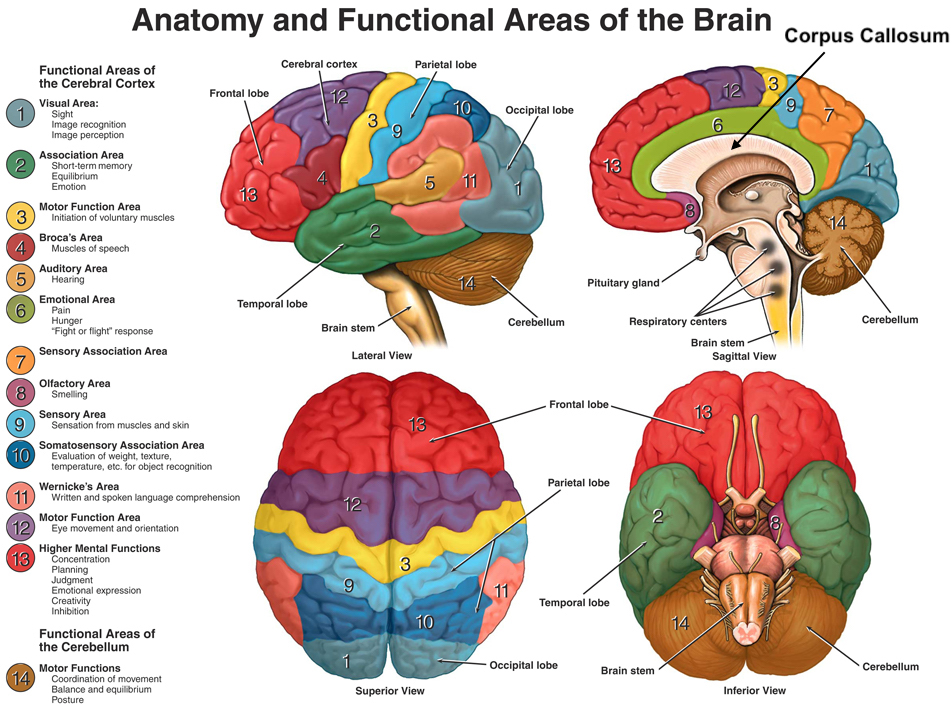

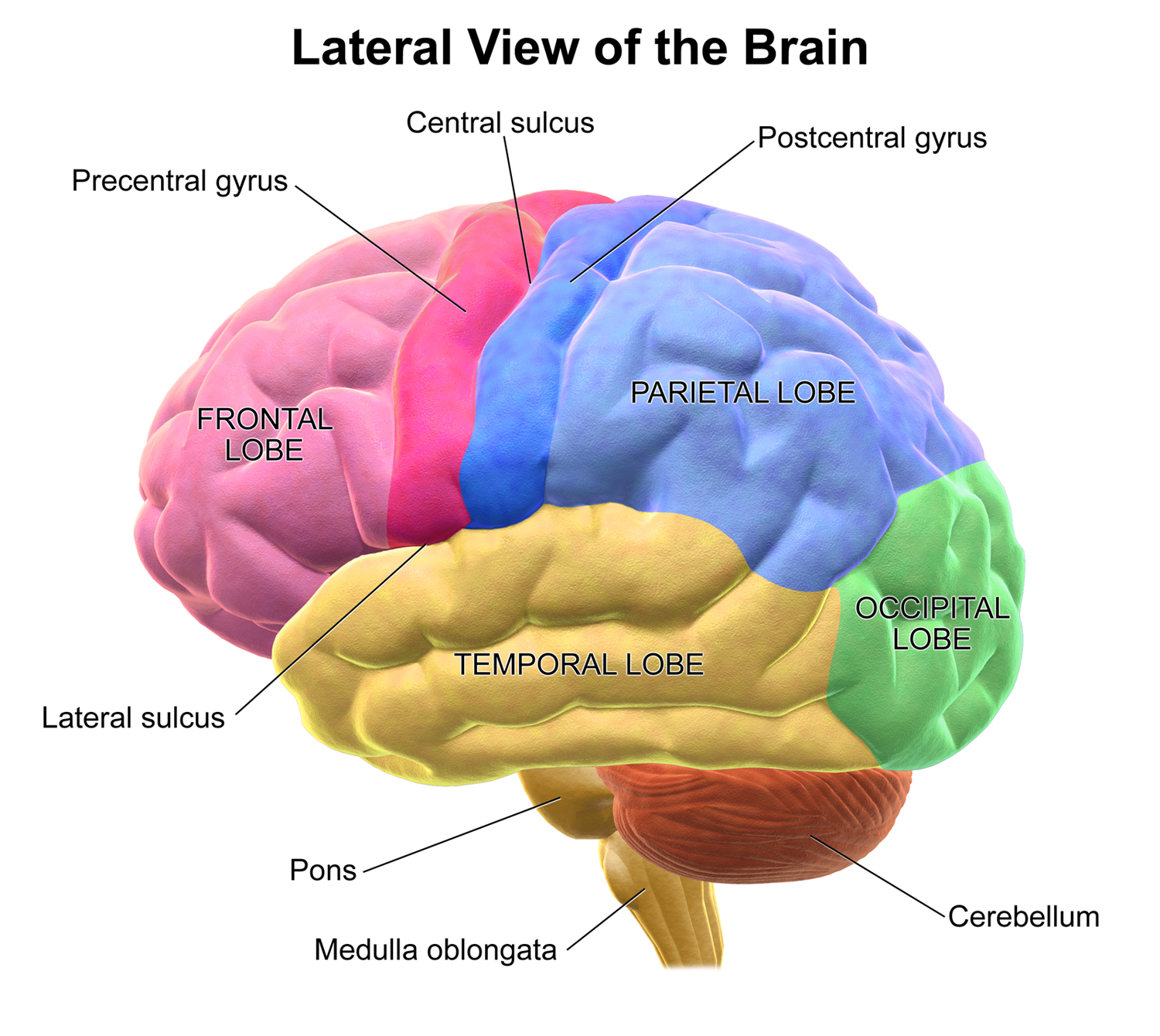

Inside the cerebrum, the outer layer—the cerebral cortex—is divided into lobes:

- Frontal lobe: planning, decision-making, and movement (via the motor cortex).

- Parietal lobe: touch, body position, and spatial sense (via the somatosensory cortex).

- Occipital lobe: vision (primary visual cortex, V1).

- Temporal lobe: hearing, language understanding, and forming long-term memories (hippocampus is key here).

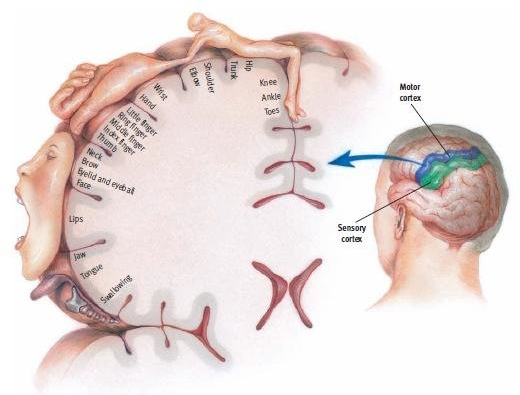

Fun fact: Each side of the motor cortex controls the opposite side of the body. Hands and lips get lots of “brain real estate” because they need very fine control and sensitivity.

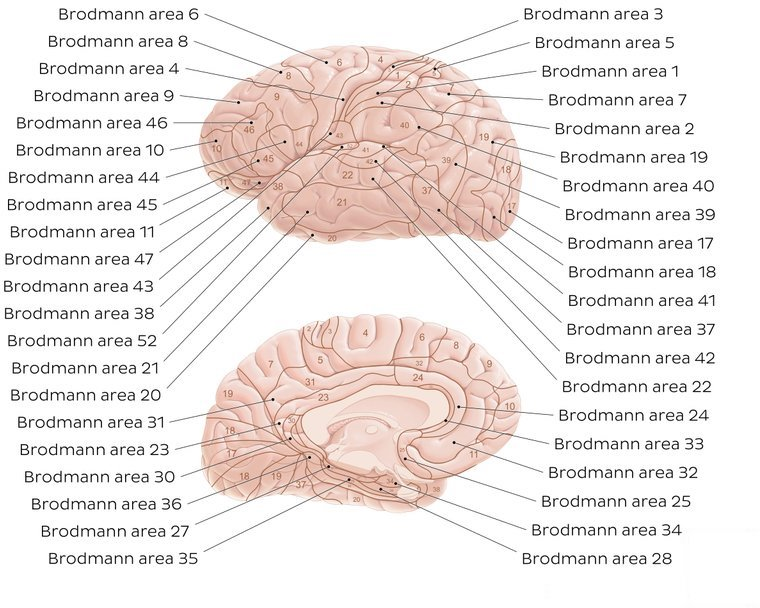

3) The cortex can be mapped like city districts (Brodmann areas)

Scientists noticed that the cortex’s layers and cells vary from place to place. Over 100 years ago, Korbinian Brodmann drew a map with numbered “areas” based on these differences. Many of these areas match functions we know today:

- Area 4: primary motor cortex (moves your body).

- Areas 3, 1, 2: primary somatosensory cortex (feeling touch).

- Area 17: primary visual cortex (seeing).

- Areas 41, 42: primary auditory cortex (hearing).

- Areas 44, 45 (usually on the left): Broca’s area (speech production).

Think of Brodmann’s map as labeled neighborhoods that specialize in different jobs.

4) How senses talk to the brain

Senses convert the outside world into signals the brain understands:

- What type (modality), how strong (intensity), where it is (location), and how long it lasts (duration).

- Receptors are like “detectors”:

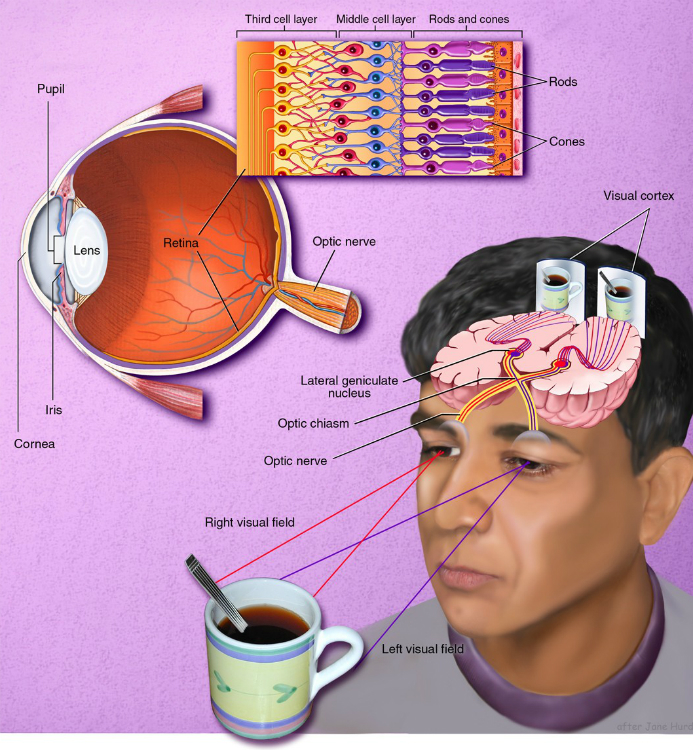

- Photoreceptors (in the eyes) detect light and color.

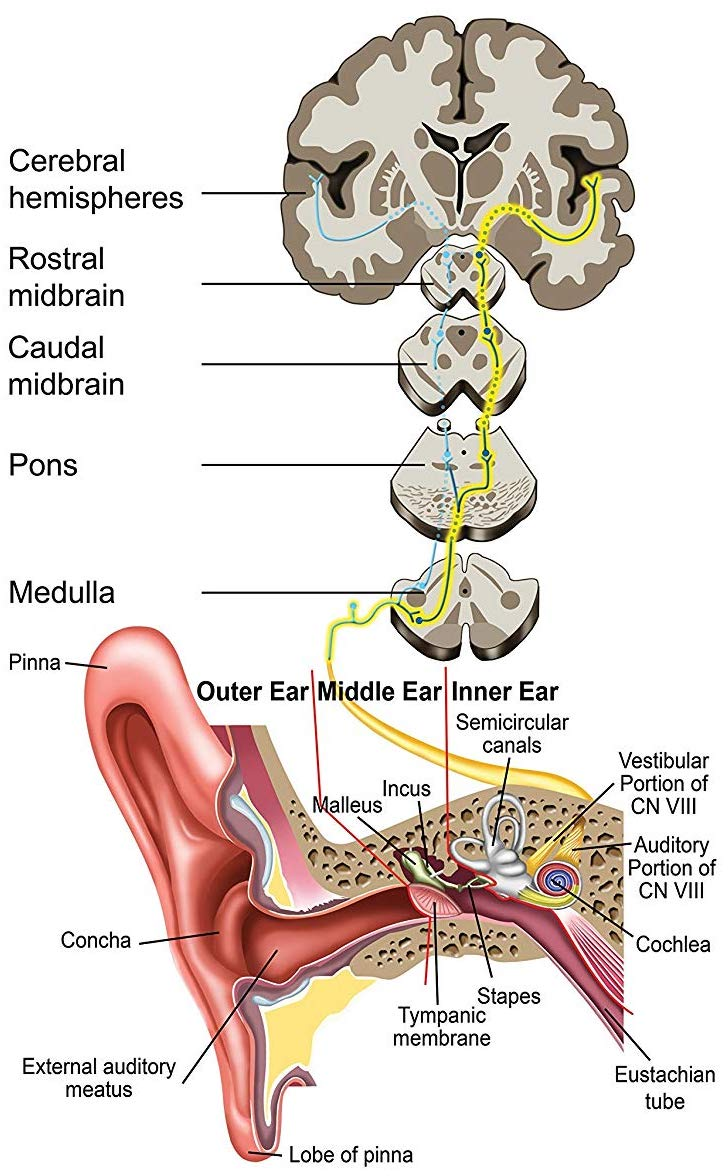

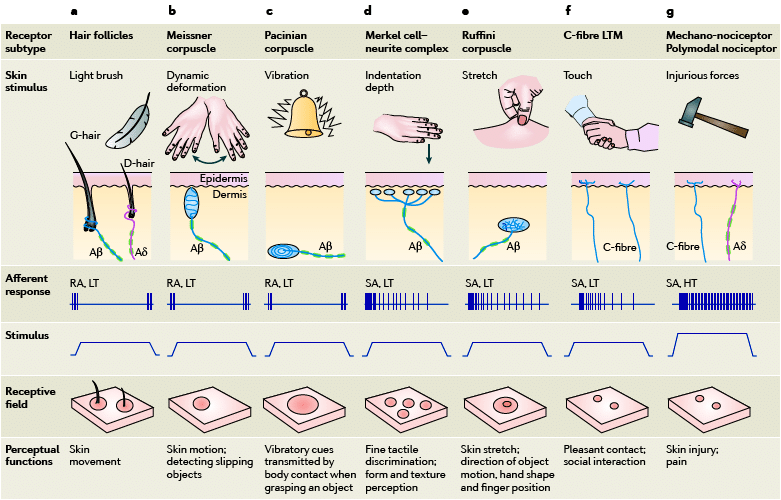

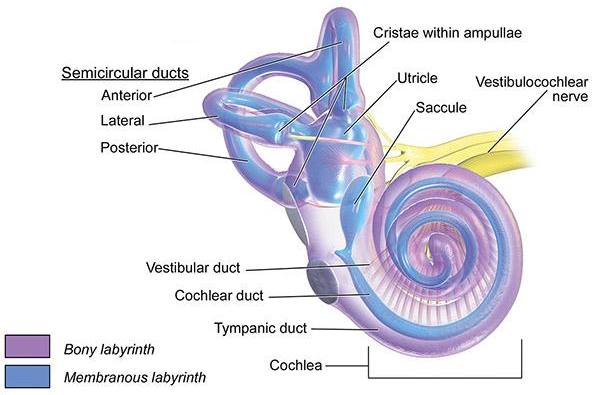

- Mechanoreceptors (in skin and inner ear) detect touch, vibration, and sound.

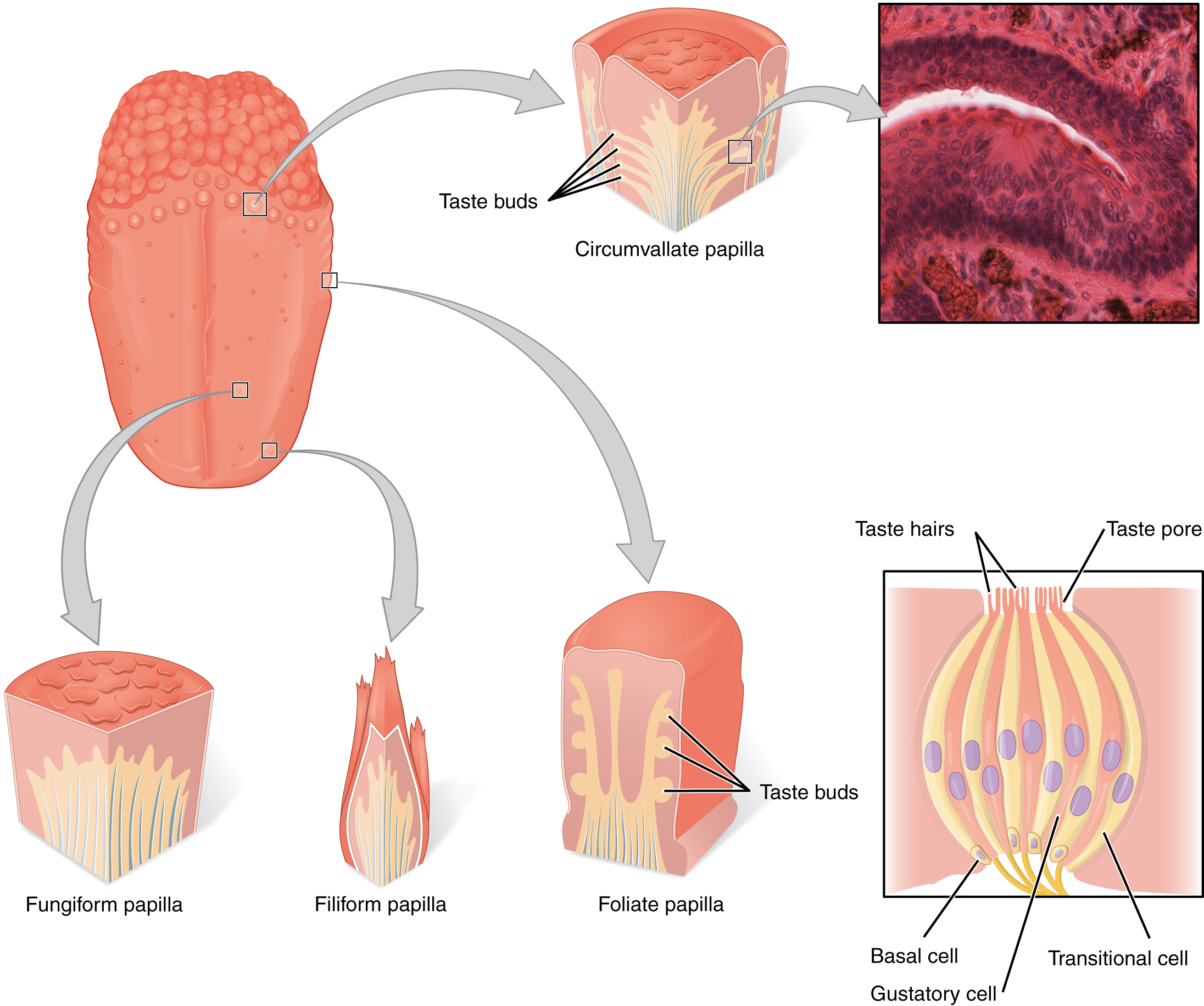

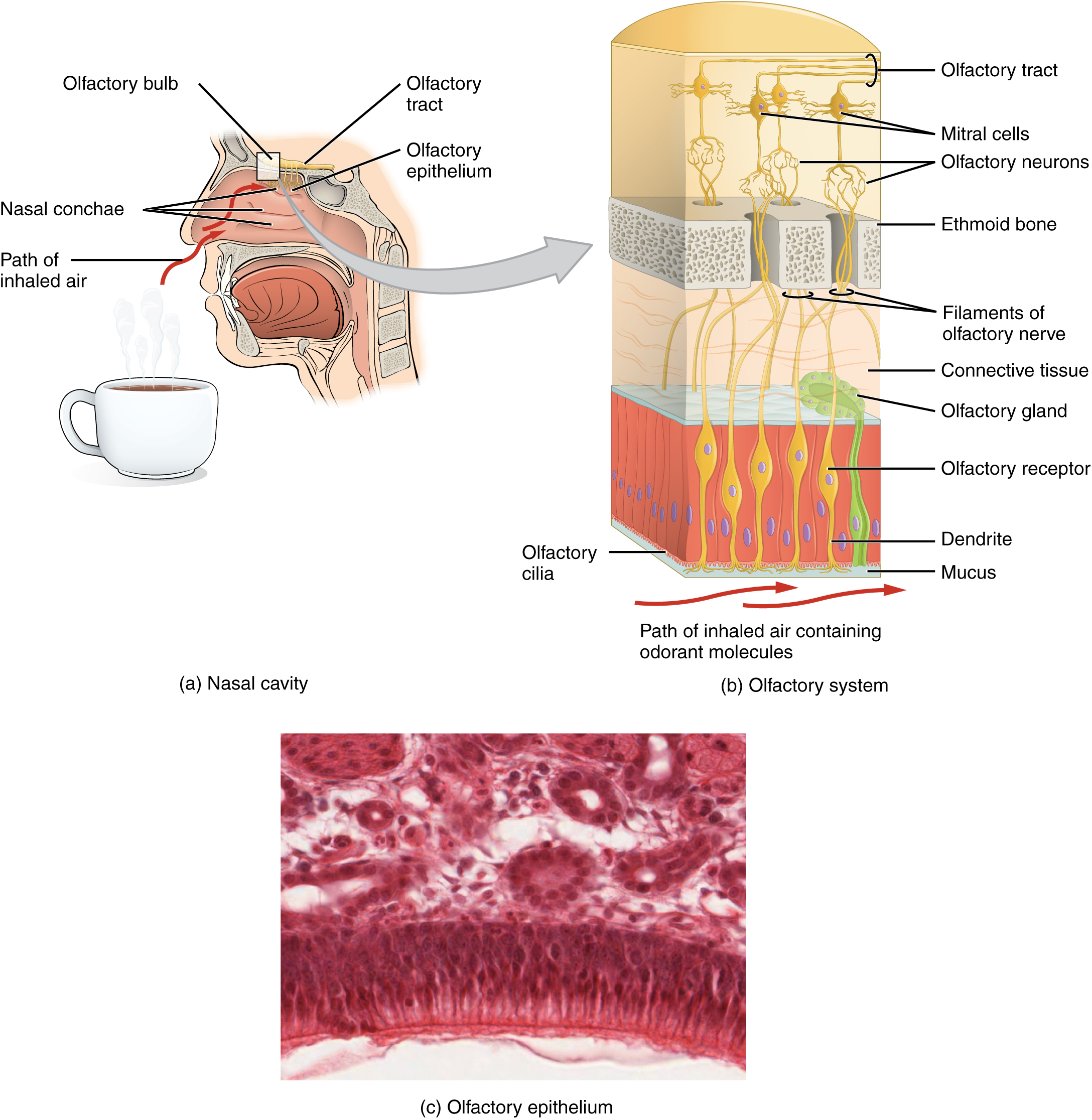

- Chemoreceptors (nose and tongue) detect smells and tastes.

- Thermoreceptors detect temperature.

- Nociceptors detect damage and can trigger pain.

Example: Vision. Light goes through the cornea and lens to the retina, turns into electrical signals, travels along the optic nerve, passes through a relay (the lateral geniculate nucleus), and reaches visual cortex (V1). From there, different pathways specialize in shape, color, and motion. Similar organized pathways exist for hearing and other senses.

Why this matters: the bigger picture

- For learning and health: Knowing what brain parts do helps doctors spot where problems might be when someone has symptoms (like speech trouble or vision loss).

- For science and technology: Understanding how brains organize and process information inspires better designs in artificial intelligence and robotics.

- For education: This “map-first” overview makes the complex brain easier to navigate, preparing readers for the next steps—how neurons work (Part 2) and how high-level thinking happens (Part 3).

In short, this paper gives you a clear map of the brain’s “places and jobs,” and a starter guide to how your senses turn the world into your experience.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The paper provides a broad, descriptive overview but leaves several concrete issues unresolved that future research (and future versions of the tutorial series) could address:

- Lack of mechanistic links from anatomy to computation and behavior: no multiscale models connecting cellular/microcircuit organization to systems-level dynamics and cognitive functions.

- Cross-species homology mapping remains unresolved: distortions of the forebrain (e.g., teleost eversion, avian specializations) complicate region-to-region correspondence; needs principled registration methods aligning cytoarchitecture, connectivity, and function across species.

- Absence of developmental and lifespan trajectories: how the introduced structures emerge, reorganize, and decline from embryogenesis through aging is not treated; longitudinal, multimodal data are needed.

- Individual variability is not addressed: inter-individual differences in anatomy (e.g., sulcal patterns), functional localization (e.g., language, motor maps), and lateralization require population-level atlases with uncertainty quantification and subject-specific parcellation methods.

- Glial, vascular, and neuromodulatory systems are largely omitted: roles of astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes, neurovascular coupling, and neuromodulators (e.g., dopamine, acetylcholine) in shaping the described circuits remain to be integrated.

- Cerebellar cognition is acknowledged but unresolved: the extent, specificity, and mechanisms of cerebellar contributions to language, attention, affect, and higher-order prediction require causal human studies (lesion, stimulation) and cross-species circuit mapping.

- Diencephalon knowledge gaps persist:

- Habenula: poorly understood roles in reward/aversion and mood; needs human in-vivo imaging with task paradigms, tractography, and causal perturbation where feasible.

- Zona incerta: function “still not determined”; requires targeted circuit dissection (e.g., high-resolution MRI, invasive recordings in clinical populations, animal optogenetics) and behavioral assays.

- Hypothalamus: nucleus-specific circuits for homeostasis and “four Fs” remain under-specified in humans; calls for fine-grained nuclei mapping, connectomics, and hormonal readouts linked to behavior.

- Endocrine pathway distinctions are blurred: clearer separation of hypothalamic releasing hormones versus pituitary effector hormones and their feedback loops is needed, with corrected hormone attributions and quantitative control diagrams.

- Brainstem arousal and sleep-wake circuitry is oversimplified: detailed ascending arousal pathways (LC, Raphe, basal forebrain, PPN), their neuromodulators, and interactions with thalamocortical loops remain to be mapped functionally in humans.

- Brodmann area (BA) limitations are not resolved:

- BA boundaries vary across individuals and cannot be identified in-vivo with current routine imaging; need individualized parcellation combining quantitative MRI, myelin maps, receptor mapping, and genetics.

- Mapping from cytoarchitecture to function is approximate; requires systematic comparisons of BA with modern multimodal atlases (e.g., HCP-MMP1.0), task/rs-fMRI, and intracranial electrophysiology.

- Motor and somatosensory homunculi are presented statically: plasticity with learning, development, and after injury (e.g., amputation) and asymmetries across hemispheres are unaddressed; longitudinal and interventional studies are needed.

- Hemispheric specialization beyond classic language areas is not covered: systematic mapping of lateralization across domains (attention, emotion, social cognition) and its anatomical bases is missing.

- Visual system open questions remain:

- Mechanisms integrating shape, color, and motion streams in humans and their laminar/circuit implementation are incomplete; requires high-field laminar fMRI, MEG/ECoG, and computational modeling.

- Quantitative connectivity and dynamics along the anterior/posterior pathways (retina → LGN → V1 → extrastriate networks) need human-validated tractography aligned with timing-resolved physiology.

- Roles and extra-visual targets of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) in humans—conscious vision versus non-image functions—need clarification via melanopsin-selective psychophysics and imaging.

- Sensory receptor mechanisms are only sketched:

- Thermoreception mechanisms are “unclear”; requires molecular characterization (e.g., TRP channels), in-vivo recordings, and behavioral correlates in humans.

- Nociceptor subtypes and central integration (e.g., spinal–thalamic–cortical pathways) and their modulation by context remain to be detailed.

- Multisensory integration is omitted: how visual, auditory, somatosensory, vestibular, olfactory, and gustatory signals are combined (e.g., in superior colliculus, STS, parietal cortex) needs causal mapping and computational accounts.

- Incomplete sensory system coverage: the auditory section is truncated and vestibular, olfactory, gustatory, and somatosensory cortical pathways lack the depth given to vision; parity in circuit-level detail is needed.

- Connectome-level organization is absent: mesoscale and macroscale connectivity (structural and effective) among the introduced regions—and how topology supports function—are not synthesized; calls for integration of tracer, diffusion MRI, and perturbational data.

- Clinical and translational links are missing: how anatomical variances and circuit dysfunctions relate to neurological/psychiatric disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s, depression, epilepsy) and guide interventions is not addressed.

- Sex differences, hormonal state, and genetic influences are not covered: systematic effects on anatomy, connectivity, and function should be quantified and incorporated into normative models.

- Methodological rigor is limited by reliance on secondary sources (e.g., Wikipedia): claims and figures should be cross-validated with primary, peer-reviewed literature and updated systematic reviews.

- Nomenclature and atlas harmonization are not discussed: inconsistencies across cytoarchitectonic, receptor, connectivity, and functional parcellations need reconciliation and standardized reference spaces.

- Integration across the planned tutorial series is not specified: explicit bridges from this anatomical overview to forthcoming neuron-level and cognitive-function tutorials (shared notation, datasets, and models) would enable a cohesive, cumulative framework.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.