Basic Neural Units of the Brain: Neurons, Synapses and Action Potential

Abstract: As a follow-up tutorial article of [29], in this paper, we will introduce the basic compositional units of the human brain, which will further illustrate the cell-level bio-structure of the brain. On average, the human brain contains about 100 billion neurons and many more neuroglia which serve to support and protect the neurons. Each neuron may be connected to up to 10,000 other neurons, passing signals to each other via as many as 1,000 trillion synapses. In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell. Such signals will be accumulated as the membrane potential of the neurons, and it will trigger and pass the signal pulse (i.e., action potential) to other neurons when the membrane potential is greater than a precisely defined threshold voltage. To be more specific, in this paper, we will talk about the neurons, synapses and the action potential concepts in detail. Many of the materials used in this paper are from wikipedia and several other neuroscience introductory articles, which will be properly cited in this paper. This is the second of the three tutorial articles about the brain (the other two are [29] and [28]). The readers are suggested to read the previous tutorial article [29] to get more background information about the brain structure and functions prior to reading this paper.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

A Simple Guide to “Basic Neural Units of the Brain: Neurons, Synapses and Action Potential”

Overview: What this paper is about

This paper is a beginner-friendly tour of how the brain sends and receives information. It explains three main building blocks:

- neurons (the brain’s “message-carrying” cells),

- synapses (the tiny gaps where messages jump from one cell to another), and

- action potentials (the electrical spikes that carry messages along a neuron).

It also touches on helpful support cells called glia and the chemicals (neurotransmitters) that help neurons talk to each other.

Goals: What questions it answers

The paper aims to answer, in simple terms:

- What do neurons look like and how are they built?

- How do neurons send signals within themselves and to other cells?

- What are synapses, and how do chemical and electrical messages get across them?

- What is an action potential, and when does it happen?

- What roles do support cells (glia) and brain chemicals (neurotransmitters) play?

Approach: How the paper explains things

This is a tutorial, not a lab experiment. The author gathers trusted information (e.g., from textbooks and Wikipedia), uses clear diagrams, and walks you through the basic ideas step by step. Think of it as a guided museum tour of brain cells.

To make the science feel familiar, here are some everyday analogies used throughout:

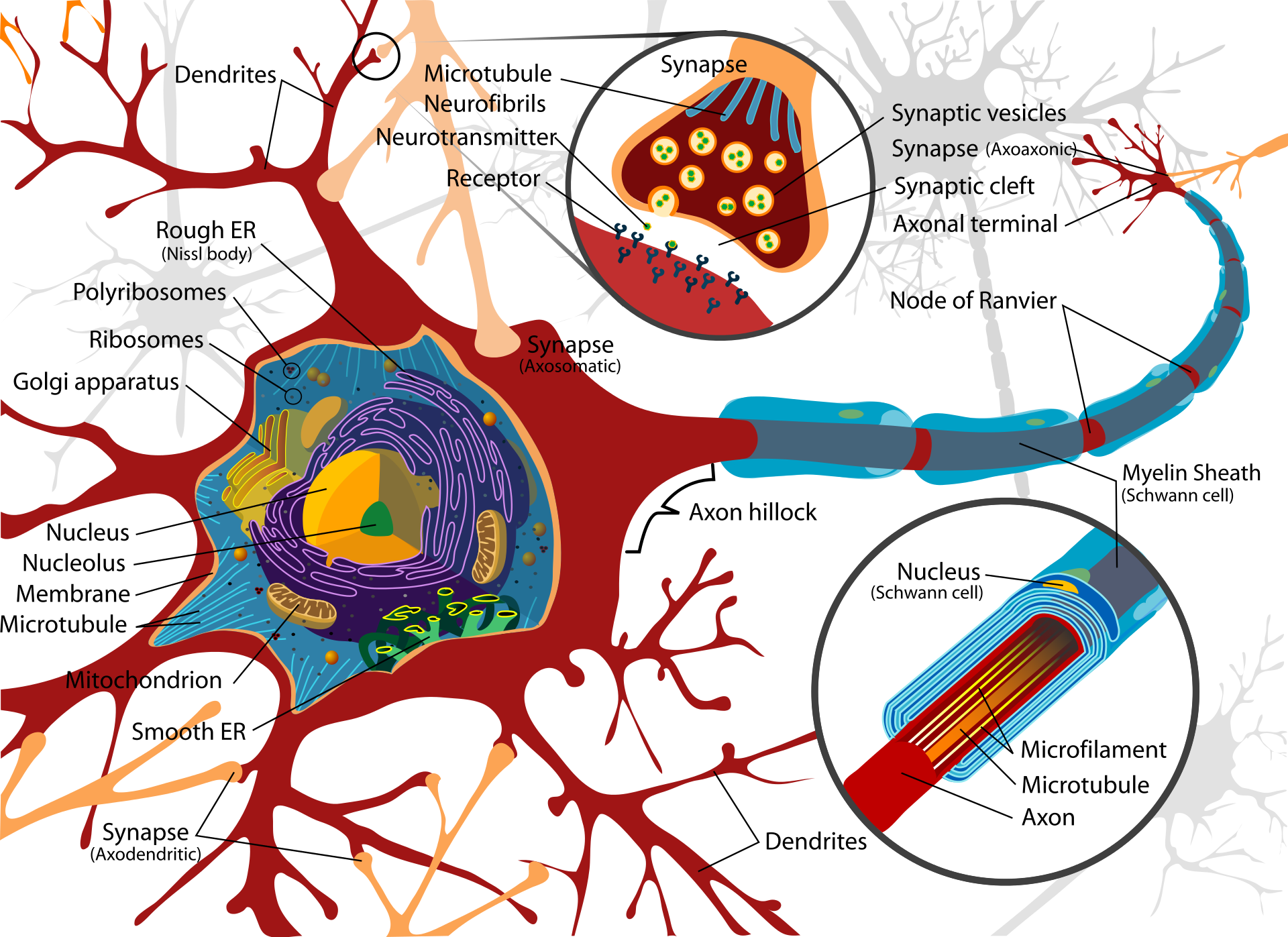

- Neuron = a long, thin wire with a control center (cell body), input branches (dendrites), and one long output cable (axon).

- Myelin = insulation on the wire that helps signals travel faster.

- Nodes of Ranvier = small gaps in the insulation that boost the signal along the way.

- Synapse = a tiny gap between two cells, like two plugs almost touching.

- Neurotransmitters = chemical “text messages” that carry the signal across the gap.

- Ion channels and pumps = doors and doormen in the cell’s membrane, controlling which charged particles (ions) go in or out.

- Membrane potential = a tiny battery across the cell’s surface; it powers signaling.

- Action potential = a fast electrical “spike” or pulse that zips down the axon—like hitting “send” on a message.

Key ideas and what the paper explains

1) Neurons: the main signal carriers

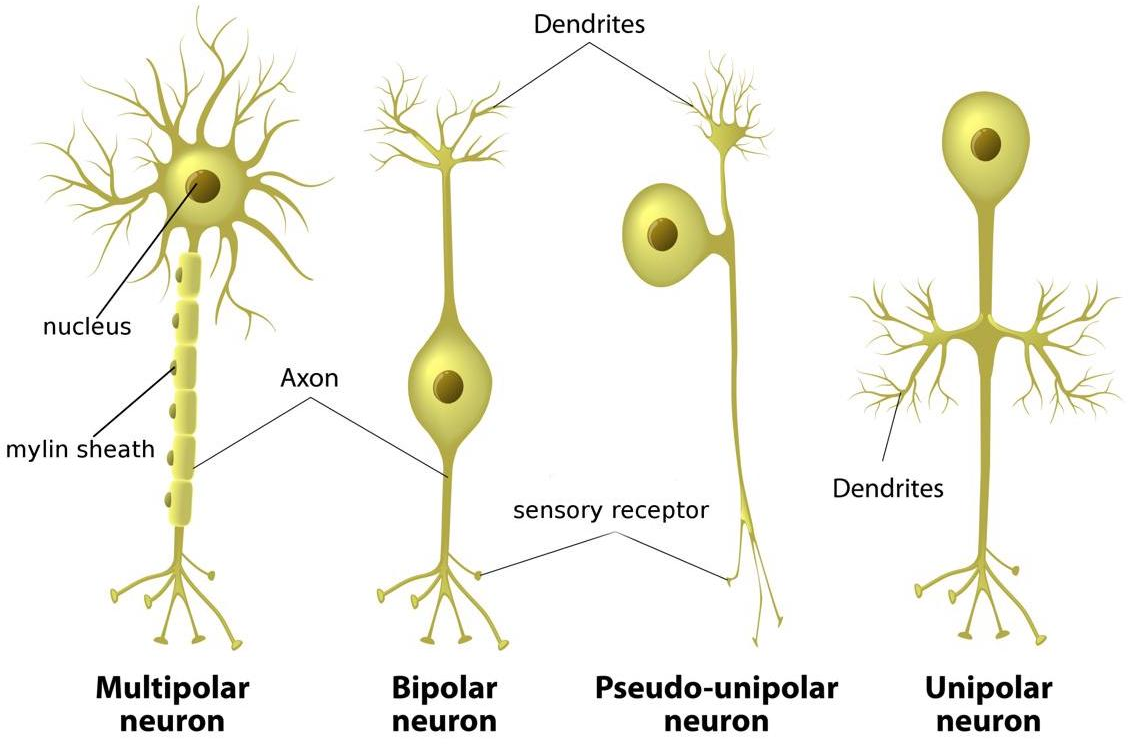

- Structure: A neuron has a cell body (soma) with a nucleus, many short input branches (dendrites), and one long output cable (axon). The axon ends in terminals that connect to other cells.

- Differences between dendrites and axons: Dendrites bring information in; axons send it out. Dendrites are often rough and branching; axons are smoother, can be insulated by myelin, and branch farther from the cell body.

- Myelin and speed: Myelin (insulation) helps messages move quickly. The signal “hops” between gaps in myelin (nodes of Ranvier), speeding things up.

- Classification: Neurons come in different shapes (unipolar, bipolar, multipolar, anaxonic, pseudounipolar) and jobs:

- Afferent (sensory): bring info from the body to the brain/spinal cord.

- Efferent (motor): send commands from the brain/spinal cord to muscles.

- Interneurons: connect neurons to other neurons and help with processing.

2) Membrane potential and action potentials: the brain’s electrical language

- The cell membrane keeps different ions (like sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium) inside vs. outside, creating a tiny voltage (like a charged battery).

- When inputs push that voltage past a threshold, an action potential (a quick, all-or-nothing spike) fires and travels down the axon.

- This is how the neuron says “yes” loudly enough to pass the message on.

3) Synapses: how neurons talk to each other

- Chemical synapses: The electrical spike reaching the axon terminal triggers vesicles (tiny bubbles) to release neurotransmitters into the synaptic gap. These chemicals bind to receptors on the next cell and change its voltage—pushing it to fire (excitatory) or to hold back (inhibitory).

- Electrical synapses: Some cells are directly connected by special channels (gap junctions) that let electricity flow straight through, which is very fast but less flexible.

- Neurotransmitters: Common ones include glutamate (often excitatory) and GABA (often inhibitory), plus dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, and others. They work briefly and are then broken down or taken back up.

- Vesicle cycle and recycling: Vesicles store neurotransmitters, release them, and then get recycled—either by fully merging with the cell membrane or by “kiss-and-run” (quickly releasing and resealing), depending on how busy the synapse is.

4) Glia: the support team that does more than support

- Glial cells (like astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia) nourish, protect, and insulate neurons. We now know some glia also help with communication and learning-related changes (neuroplasticity).

5) Brain networks and plasticity: how learning happens

- Each neuron can connect to thousands of others, making up to hundreds of trillions of connections across the brain.

- When two neurons talk a lot, their connection usually gets stronger. This “rewiring” over time is how learning and memory can form.

Main takeaways and why they matter

Here are the most important points the paper highlights:

- The brain uses both electricity (action potentials) and chemistry (neurotransmitters) to pass messages.

- Neuron structure shapes how signals enter, travel, and exit the cell.

- Synapses come in two main types (chemical and electrical). Chemical synapses are slower but flexible; electrical synapses are faster but simpler.

- Excitatory and inhibitory signals balance each other so the brain doesn’t overload or go silent.

- Glia are not just “helpers”; they are active players in brain function.

- Connections between neurons are not fixed—experience strengthens or weakens them. That’s the basis of learning.

These ideas are important because they explain everyday experiences (learning, memory, reflexes), medical issues (how drugs work, why diseases like epilepsy or Parkinson’s affect movement and mood), and even inspire technology (artificial neural networks in AI).

Implications: What this means for the future

- Medicine and mental health: Knowing how synapses and neurotransmitters work helps doctors design better treatments for depression, anxiety, epilepsy, Parkinson’s, and more.

- Education and learning: Understanding plasticity supports better study habits and teaching strategies that match how the brain changes with practice.

- Technology and AI: Brain-inspired ideas help build smarter algorithms and brain–computer interfaces.

- Research directions: Scientists are still discovering how glia contribute to communication and how different neurotransmitters fine-tune brain circuits—work that could lead to new therapies.

In short, this tutorial gives you the “wiring diagram” and the “rules of the road” for brain signals. With that foundation, you can understand how the brain learns, how medicines can help, and how brain-inspired tech is designed.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a consolidated list of knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that remain unresolved or are only superficially addressed in the paper, framed to guide future research:

- Quantification uncertainty: Reported numbers (e.g., ~100B neurons, 100–1,000 TB memory, 100–1,000T synapses, 5–50 Hz firing rates) lack primary sources, confidence intervals, regional variability, and species/developmental dependence.

- Glia function mechanisms: The extent, molecular pathways, and kinetics by which astrocytes and other glia modulate synaptic transmission and neuroplasticity (tripartite/quad-partite synapse) remain unspecified and need causal, in vivo tests.

- Axon–dendrite disambiguation: Objective, scalable criteria and markers (molecular, ultrastructural, or electrophysiological) to reliably differentiate axons from dendrites in heterogeneous neurons are not provided.

- Subcellular ion channel topography: The distributions, densities, and activity-dependent plasticity of ion channels/pumps across soma, AIS, dendrites, and axon (and their impact on thresholds and excitability) are not quantified.

- Action potential biophysics: No explicit, predictive models (e.g., Hodgkin–Huxley, cable theory) link channel kinetics to spike initiation, propagation, and back-propagation; parameterization across neuron classes is absent.

- Electrical synapses: Prevalence, molecular composition (connexin/innexin isoforms), plasticity, and functional roles of gap junctions across mammalian brain regions and behavioral states are not characterized.

- Synaptic adhesion molecules (SAMs): Which SAMs stabilize which synapse classes, and how SAMs govern synaptogenesis, alignment, and plasticity, remain open for systematic mapping and perturbation.

- Vesicle docking ambiguity: The molecular determinants and structural intermediates of synaptic vesicle docking are explicitly stated as poorly understood; high-resolution, live-cell docking assays and structure–function studies are needed.

- Priming diversity: Isoform-specific roles and kinetics of Munc13/RIM/RIM-BP across synapse types, and their calcium and second-messenger dependencies, are not delineated.

- Release coupling geometry: The nanometer-scale coupling distances between Ca2+ channels and vesicles, the specific Ca2+ channel subtypes engaged (P/Q, N, R, T), and their regulation across activity regimes are not addressed.

- Endocytosis pathways in vivo: The relative contributions and state dependence of full-collapse fusion versus kiss-and-run in mammalian central synapses during physiological firing patterns (temperature, Ca2+, metabolic constraints) remain unresolved.

- Vesicle pool quantification: In vivo sizes, turnover rates, molecular markers, and conversion dynamics between readily releasable, recycling, proximal, and reserve pools across synapse classes and activity states are not provided.

- Transporter stoichiometry context: Conditions (pH, temperature, membrane potential) under which the presented vesicular transporter stoichiometries hold, and isoform-specific differences, are unspecified.

- Neurotransmitter diversity and co-release: Systematic mapping of neurotransmitter co-release, co-transmission with neuropeptides, and the balance between synaptic versus volume transmission is not covered.

- Receptor–effector mapping: The paper does not link transmitter classes to receptor subtypes, downstream second-messenger cascades, and time scales of postsynaptic effects (fast ionotropic vs slow metabotropic).

- Clearance dynamics: Quantitative spatiotemporal models of neurotransmitter diffusion, uptake (transporters), enzymatic degradation, and the influence of extracellular space/matrix are missing.

- Dendritic computation: Mechanisms of dendritic integration (local NMDA and Ca2+ spikes, branch-specific computation), E/I balance shaping, and bAP modulation of plasticity are not treated.

- Plasticity rules: Molecular induction and expression mechanisms of LTP/LTD, STDP windows, and structural spine plasticity—and their relationship to vesicle pools and release probability—are not discussed.

- Myelin plasticity: Activity-dependent changes in myelination, node of Ranvier spacing, and their consequences for conduction velocity, temporal precision, and circuit synchrony remain unexplored.

- Energetic constraints: How mitochondrial distribution, ATP supply, and Ca2+ buffering at terminals constrain release probability, vesicle recycling, and synaptic reliability is not analyzed.

- Developmental and aging trajectories: How neuronal morphology, channel composition, synapse types, and vesicle/receptor machinery evolve across development and aging (including roles of neuromelanin/lipofuscin) are not elaborated.

- Pathophysiology linkage: The paper does not connect these mechanisms to disease (e.g., channelopathies, synaptopathies, demyelination), limiting translational relevance and hypothesis generation.

- Circuit-level scaling: How cell-level parameters (channels, vesicle pools, receptor kinetics) scale to network computation, learning capacity, and the validity of memory capacity estimates are not modeled or tested.

- Synapse-type function: Functional roles of non-axodendritic synapses (axo-axonic, dendro-dendritic, somato-somatic) in specific circuits and behaviors remain to be systematically mapped.

- Interneuron heterogeneity: Differences in synaptic machinery, release kinetics, and plasticity across interneuron subtypes (e.g., PV, SST, VIP) are not addressed.

- Methodological limitation: Heavy reliance on secondary sources (e.g., Wikipedia) without primary literature synthesis limits rigor, leaves key claims uncited, and obscures experimental uncertainties.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.