Controllable LLM Reasoning via Sparse Autoencoder-Based Steering

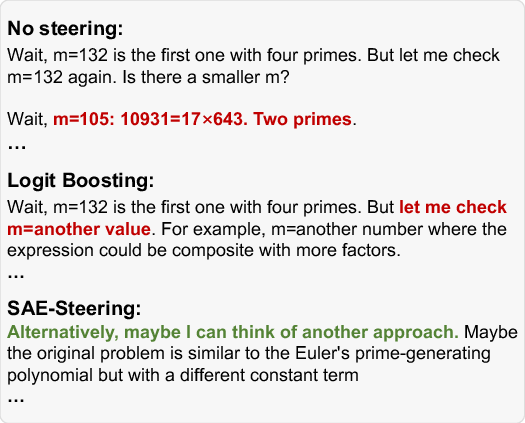

Abstract: Large Reasoning Models (LRMs) exhibit human-like cognitive reasoning strategies (e.g. backtracking, cross-verification) during reasoning process, which improves their performance on complex tasks. Currently, reasoning strategies are autonomously selected by LRMs themselves. However, such autonomous selection often produces inefficient or even erroneous reasoning paths. To make reasoning more reliable and flexible, it is important to develop methods for controlling reasoning strategies. Existing methods struggle to control fine-grained reasoning strategies due to conceptual entanglement in LRMs' hidden states. To address this, we leverage Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) to decompose strategy-entangled hidden states into a disentangled feature space. To identify the few strategy-specific features from the vast pool of SAE features, we propose SAE-Steering, an efficient two-stage feature identification pipeline. SAE-Steering first recalls features that amplify the logits of strategy-specific keywords, filtering out over 99\% of features, and then ranks the remaining features by their control effectiveness. Using the identified strategy-specific features as control vectors, SAE-Steering outperforms existing methods by over 15\% in control effectiveness. Furthermore, controlling reasoning strategies can redirect LRMs from erroneous paths to correct ones, achieving a 7\% absolute accuracy improvement.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Plain‑English Summary of “Controllable LLM Reasoning via Sparse Autoencoder‑Based Steering”

1) What is this paper about?

This paper is about teaching big AI reasoning models (the kind that “think out loud” before answering) to use the right thinking strategy at the right time. Sometimes these models choose poor strategies on their own—like chasing a wrong idea for too long—so the authors propose a way to gently steer the model’s “train of thought” toward better strategies, such as re-reading the question, making a plan, or double‑checking in a new way.

2) What questions did the researchers ask?

In simple terms, they asked:

- Can we control which thinking strategy an AI uses while it’s thinking?

- Can we find a precise “control knob” inside the AI that turns a specific strategy up or down?

- Does this kind of control actually help the AI avoid mistakes—or even fix them after they happen?

They focused on five common strategies: understanding the problem, planning steps, backtracking after a mistake, checking the answer from another angle, and trying “what if” assumptions.

3) How did they do it? (Methods explained simply)

Think of the AI’s mind as a huge music mixer with thousands of tiny sliders (its internal signals). These sliders are all tangled together, so moving one can affect many sounds at once—making it hard to control just one “instrument” (a single strategy).

The authors use a tool called a Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) to untangle this mess:

- Sparse Autoencoder (SAE): Imagine you record a full band (the AI’s hidden thoughts) and then use special software to split the music into separate tracks: drums, guitar, vocals, etc. An SAE does something like that—it takes the AI’s mixed‑up signals and breaks them into many cleaner “feature tracks,” where each track ideally represents one clear idea or behavior. “Sparse” means only a few tracks play at a time, which keeps things tidy and understandable.

Once they have these feature tracks, they try to find the few that control specific reasoning strategies. But there are tens of thousands of tracks—too many to test one by one—so they use a two‑stage “find the best candidates” process called SAE‑Steering:

- Stage 1: Fast screening (keyword magnets)

- Each next word the AI might say has a score before it’s chosen (called a “logit”—think of it as a “how likely is this word?” score).

- For each feature track, they quickly estimate whether turning that track up would increase the scores of strategy‑related words (like “plan,” “assume,” “check,” “another way”) using a technique similar to looking through a “logit lens.”

- If a feature strongly boosts several strategy keywords—and doesn’t boost random words more—it’s a good candidate. This step is super fast and removes over 99% of unhelpful features.

- Stage 2: Careful testing (auditions)

- For the small set of candidates, they run short “thinking” tests: generate the AI’s next steps with and without the feature turned on, then ask judges (another AI set up as a careful grader) which version shows the target strategy more clearly. They rank the features by how often they succeed.

- The top feature becomes the “control vector”—like the exact slider you move to encourage a strategy.

Finally, during generation, they “nudge” the AI by adding this control vector for a short stretch of tokens (words), with just enough strength to influence behavior without causing weird repetition.

4) What did they find, and why is it important?

Here are the main results and what they mean:

- Better control than previous methods:

- Their SAE‑Steering method was over 15% better at making the AI use the desired strategy than strong baselines that tried steering with prompts or with less precise vectors. This shows that untangling the AI’s internal features first makes control much cleaner and more reliable.

- Not just keyword tricks:

- Simply boosting strategy words (like “plan” or “assume”) didn’t actually change the AI’s thinking behavior much. SAE‑Steering, which targets deeper features, did change behavior—so it’s acting on real thinking patterns, not surface words.

- Efficient search:

- The fast “logit lens” screening was much more precise than older “activation strength” tricks (about 28% better in precision when recalling good features). In other words, checking how a feature affects word scores is a better hint of real control than just seeing how “loud” the feature is.

- Works across tasks:

- They trained on math reasoning but also tested on science questions (GPQA), and the control still worked well. That suggests these strategy features are somewhat general.

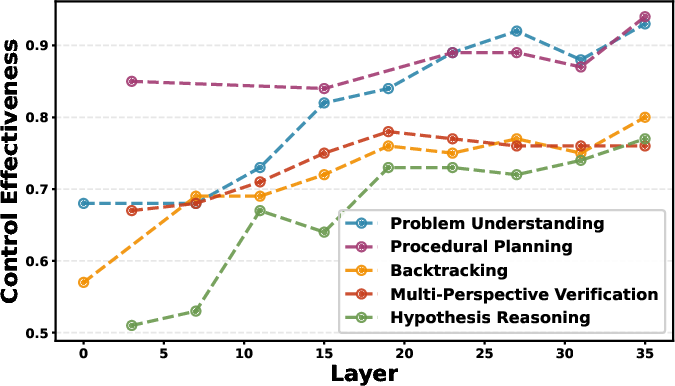

- Where in the model it works best:

- The most useful “strategy tracks” live in the deeper layers of the model (later stages of its thinking pipeline), and steering there works best.

- Helps fix mistakes:

- When the AI had already given a wrong answer, extending its thinking and steering it to better strategies improved correction rates by about 7% (absolute). On a math set, the best case corrected about one‑third of wrong answers—hard, but a real boost over baselines.

Why this matters: It shows we can move beyond “ask nicely in the prompt” and instead directly guide how the AI thinks, leading to more reliable, flexible reasoning.

5) What’s the bigger impact?

- More trustworthy AI thinking: By choosing the right strategy at the right time (re‑read, plan, backtrack, verify differently, or try an assumption), AI can avoid getting stuck and produce better, clearer solutions.

- Practical error recovery: Even after a mistake, nudging the AI to backtrack or verify from a new angle can rescue answers that would’ve stayed wrong.

- Safer and more controllable systems: Fine‑grained control helps align AI behavior with human goals, especially on long, complex problems where prompts alone can fail.

- A roadmap for future tools: The same idea—untangle internal features, then steer the right ones—could be used to control other behaviors beyond reasoning strategies.

In short, the paper shows a smart way to find and move the right “sliders” inside an AI’s mind so it thinks more like a careful problem solver, not just a good guesser.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, framed as concrete, actionable avenues for future work:

- Strategy coverage: Only five strategies are studied; it remains unknown whether the approach generalizes to other fine-grained strategies (e.g., decomposition, constraint-checking, uncertainty articulation) or to task-specific heuristic strategies.

- Multi-strategy control: The method selects a single feature per strategy; how to compose, prioritize, or schedule multiple strategies (and their features) simultaneously without interference is unexplored.

- Dynamic control policies: Steering strength α is chosen via a manual search and is fixed over T tokens; adaptive schedules (time-varying α, early stopping, or context-aware gating) and per-instance tuning are not investigated.

- Early vs late intervention: Interventions are mainly at the last layer (and layer ablations only for one model); when and where to intervene (early, middle, late, or multi-layer) for different strategies and tasks lacks a principled treatment.

- Layer-wise SAEs: SAEs are trained on a single layer; whether multi-layer SAEs, cross-layer feature sets, or layer-specific dictionaries yield stronger or safer control is untested.

- Generalization across model sizes and families: Experiments use two 8B open models; behavior on larger models, instruction-tuned vs base models, decoder vs encoder–decoder architectures, and closed-source o1-like systems is unknown.

- Tokenizer and language dependence: Strategy keyword recall and logit contributions may be tokenizer- and language-specific; cross-lingual control and robustness to different tokenizations are not evaluated.

- Domain breadth: SAEs are trained on mixed chat/reasoning corpora and evaluated on math and science; transfer to code, legal, medical, multimodal, or open-domain dialogue is unassessed.

- End-to-end utility: Beyond error-correction experiments, there is no systematic study of answer accuracy, compute cost, and time-to-solution when steering is used proactively during standard inference.

- Negative side effects: The impact of steering on hallucinations, factuality, calibration, verbosity, and coherence (especially under strong α) is not quantified.

- Failure modes: Conditions under which steering fails (e.g., contradictory goals, adversarial prompts, highly ambiguous tasks) and automatic failure detection/fallback mechanisms are not characterized.

- Safety/alignment risks: Steering could bypass guardrails or intensify persuasion; methods to constrain or audit steering for safety and compliance are not addressed.

- Judge dependence: Control success is judged by LLMs with majority voting; broader human evaluation, robustness to judge choice, and objective automated metrics (beyond keyword/style cues) are limited.

- Strategy verification metric: Success criteria rely on style and keyword expression; disentangling “strategy adoption” from superficial phrasing remains an open evaluation challenge.

- Causal validity of logit-lens recall: Using L = W_decT U assumes linearity and ignores layer norms, residual mixing, and non-linearities; causal tracing/ablation validations of feature–output effects are absent.

- Monosemanticity claims: The paper relies on SAE monosemanticity but provides no quantitative disentanglement metrics (e.g., feature purity, selectivity) or human interpretability audits of strategy features.

- Keyword-based recall bias: Stage 1 relies on strategy-specific keywords; strategies that manifest without explicit lexical markers (multi-sentence patterns, structural plans) may be missed.

- Phrase and synonym coverage: The recall relies on top-10 token contributions; handling multiword expressions, synonyms, paraphrases, and morphology (especially across domains/languages) is underexplored.

- Alternative feature selection: Beyond ReasonScore, broader comparisons (e.g., causal mediation, gradient-based influence, SHAP/Integrated Gradients in feature space) for identifying strategy features are not performed.

- Combining features: The method selects a single top feature; whether learned mixtures or sparse sets of features yield more precise, robust steering is untested.

- Router design: The “strategy router” for error correction is only briefly described; its training data, features, generalization, and robustness (and whether it can be learned end-to-end) are unclear.

- Compute and memory cost: The overhead of training/serving SAEs (dictionary size M, K sparsity, latency for per-token injections) and scaling to larger models or multi-layer SAEs is not quantified.

- Stability across seeds/checkpoints: Reproducibility of learned features and their control effects across SAE seeds, datasets, and base-model checkpoints is not studied.

- Data shift and drift: How often SAEs must be retrained to track model updates or domain drift, and whether features remain stable over time, is unknown.

- Inter-task transfer: Features found on math reasoning transfer to GPQA; but systematic transfer maps (which features transfer where, and why) and failure analyses are missing.

- Strategy conflicts: Steering to one strategy may suppress or distort others; detecting and managing conflicts (e.g., backtracking vs forward planning) is not addressed.

- Budget/length trade-offs: Steering may increase reasoning length; systematic analysis of compute–accuracy trade-offs and policies for budget-aware control is absent.

- Baseline breadth: Comparisons omit stronger activation/weight-edit baselines (e.g., ThinkEdit, RL-based self-correction, learned intermediate interventions) and ablations against more competitive prompting methods.

- Theoretical guarantees: There is no analysis of when and why feature injection provably shifts generation towards target strategies without collateral damage.

- Robustness to adversarial prompts: The resilience of steering under adversarial or distribution-shifted inputs (e.g., prompts that mimic or negate targeted strategies) is not evaluated.

- Instance-level adaptivity: Per-instance selection of features/α/T is heuristic; learning instance-adaptive controllers or bandit/RL policies for strategy scheduling remains open.

- Multi-turn settings: Effects in interactive dialogue or tool-use settings (where strategies evolve across turns and tools) are not studied.

- Non-text modalities: Whether SAE-steering extends to multimodal LRMs (vision, audio) and multi-modal strategies (e.g., cross-modal verification) is unexplored.

- Transparency and governance: Procedures for documenting, auditing, and controlling access to steering features (particularly those that can influence safety-critical behavior) are not proposed.

Practical Applications

Practical Applications of “Controllable LLM Reasoning via Sparse Autoencoder‑Based Steering”

The paper introduces SAE-Steering, a two-stage pipeline that learns monosemantic, strategy-specific features from sparse autoencoders and injects them into an LLM’s residual stream to control fine-grained reasoning strategies (e.g., problem understanding, procedural planning, backtracking, multi-perspective verification, hypothesis reasoning). It outperforms prompt- and contrastive-activation baselines and improves post-hoc error correction by ~7% absolute. Below are actionable applications, grouped by time horizon, with sectors, potential tools/workflows, and feasibility notes.

Immediate Applications

These can be piloted today with open-source/self-hosted LLMs where internal activations are accessible and with modest engineering.

- Strategy-aware copilots for safer code and analytics [Software/DevTools]

- Use cases: enforce “plan-first then implement,” auto-trigger backtracking when tests fail, verify code changes from multiple perspectives.

- Tools/workflows: inference middleware that injects SAE features during generation; adapters for vLLM/Transformers; CI hooks to toggle strategies by task.

- Assumptions/dependencies: needs access to residual stream hooks and a trained SAE per model/layer; per-task tuning of α and T; best for open models (e.g., Llama/Qwen).

- Customer support assistants that ask better clarifying questions [Customer Service/Operations]

- Use cases: steer toward “problem understanding” and “procedural planning” to reduce misinterpretation and escalations.

- Tools/workflows: routing rules in the contact center platform that enable steering for long/ambiguous tickets; audit logs of strategy usage per case.

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain-specific keywords for Stage 1 recall may need curation; privacy controls for logging intermediate states.

- Tutoring systems that teach with explicit pedagogy [Education]

- Use cases: enforce “plan → solve → multi-perspective verification” in math/science tutoring; toggle “hypothesis reasoning” for inquiry-based learning.

- Tools/workflows: LMS plugin exposing strategy profiles per lesson; per-student strategy policies; dashboards showing strategy traces.

- Assumptions/dependencies: alignment with curriculum outcomes; mild re-tuning for domain-specific corpora improves robustness.

- Error-recovery for long-form reasoning tasks [Enterprise Knowledge/Support]

- Use cases: when a draft is wrong, continue with “backtracking” or “multi-perspective verification” rather than restarting; improves salvage rate of long outputs.

- Tools/workflows: “wait” token + strategy router to select the best corrective strategy; A/B tests against budget forcing/self-reflection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: quality depends on the router; risk of repetition if α too high; needs guardrails.

- Research writing and literature review assistants [Academia/Publishing]

- Use cases: steer to “multi-perspective verification” for claims; “hypothesis reasoning” for ideation; reduce superficial keyword boosting pitfalls.

- Tools/workflows: a plug-in to trigger strategies on sections (methods, results, discussion); citation verification workflow.

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain keyword lists; careful evaluation to avoid plausible-but-wrong citations.

- Scientific analysis copilots [R&D/Life Sciences]

- Use cases: exploratory data analysis with explicit planning; hypothesis generation with structured verification steps.

- Tools/workflows: Jupyter extension that toggles strategies during code/comment generation; stepwise verification prompts driven by activation control.

- Assumptions/dependencies: works best with transparent, local models; maintain traceability for lab notebooks.

- Contract and policy analysis with enforced verification [Legal/Compliance]

- Use cases: extract constraints (problem understanding), plan review procedures, cross-verify citations/clauses.

- Tools/workflows: DMS add-in that records strategy usage; red-flag reports when verification is skipped.

- Assumptions/dependencies: human-in-the-loop review remains essential; regulatory acceptance of activation-level steering unknown.

- Risk and report generation with reasoning governance [Finance/Enterprise Ops]

- Use cases: mandate verification steps for risk summaries; enforce backtracking on numerical inconsistencies.

- Tools/workflows: “reasoning policy” templates; governance dashboards logging strategy activation traces for audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: internal hosting for sensitive data; legal review of logging CoT-like traces.

- Agentic tool-use with controlled backtracking [Automation/Agents]

- Use cases: re-plan when tool outputs contradict; force multi-perspective checks before committing high-cost actions.

- Tools/workflows: agent framework hooks to toggle strategies pre/post tool calls; success metrics tied to task completion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: stable integration with tool outputs; careful α/T tuning to avoid overcorrection.

- LLMOps evaluation and interpretability instrumentation [ML Platform]

- Use cases: diagnose strategy failures; monitor distribution of strategies across tasks; compare steering vs prompt baselines.

- Tools/workflows: evaluation harness that replays tasks with/without steering; feature registry per model/layer; judge ensembles for validation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: LLM judges introduce bias; establish human adjudication for critical evaluations.

- Personal assistants that default to clarifying and planning [Daily Life/Consumers]

- Use cases: itinerary planning that starts with questions; home projects with explicit procedural plans; cross-checking choices (e.g., purchases).

- Tools/workflows: desktop/mobile apps wrapping local LLMs with strategy toggles; preset “clarify → plan → verify” profiles.

- Assumptions/dependencies: feasible with local open models; limited by on-device compute and memory for SAEs.

Long-Term Applications

These require further research, scaling, standardization, or regulatory acceptance before broad deployment.

- High-stakes clinical decision support with verifiable reasoning policies [Healthcare]

- Use cases: enforce multi-perspective verification and backtracking to mitigate premature closure in diagnostics.

- Tools/workflows: EHR-integrated reasoning policy engine; traceable strategy logs for clinical audit; safety interlocks on α/T.

- Assumptions/dependencies: rigorous clinical validation, bias assessment, and certification; integration with patient privacy and provenance systems.

- Regulated financial advisory and trading assistants [Finance]

- Use cases: policy-driven reasoning that mandates checks for compliance and risk; auditable verification trails.

- Tools/workflows: strategy-policy compilers; immutable reasoning audit trails; regulatory reporting of strategy adherence.

- Assumptions/dependencies: regulatory clarity on activation steering; extensive backtesting; liability frameworks.

- Robotic planning with dynamic strategy routing [Robotics/Autonomy]

- Use cases: enforce “procedural planning,” backtracking on plan failures, and hypothesis testing in simulation before execution.

- Tools/workflows: closed-loop controller that toggles strategies based on sensor discrepancies; sim-to-real validation harnesses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust multi-modal SAEs; latency-sensitive steering; safety certifications.

- Curriculum-aware pedagogical control and outcome optimization [Education]

- Use cases: adapt strategy sequencing to learner profiles; measure learning gains per strategy mix.

- Tools/workflows: strategy router trained on longitudinal outcomes; teacher dashboards; individualized strategy contracts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: IRB-approved trials; data privacy; fairness across demographics.

- Training-time integration of monosemantic control “knobs” [Model Architecture/Alignment]

- Use cases: expose stable, API-accessible strategy controls learned during pretraining/finetuning; reduce inference-time hyperparameter fragility.

- Tools/workflows: joint SAE-style objectives during pretraining; RL that rewards strategy compliance; standardized control APIs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: scalability of SAEs to frontier models; compatibility with RLHF/DPO; compute cost.

- Safety and deception mitigation via strategy suppression/encouragement [AI Safety/Governance]

- Use cases: detect and steer away from risky reasoning modes; enforce verification in sensitive queries.

- Tools/workflows: red-teaming suites that map risky features; policy packs that suppress dangerous strategies and elevate safe ones.

- Assumptions/dependencies: broader feature libraries beyond the five strategies; robust generalization and adversarial testing.

- Cross-model feature marketplaces and interoperability standards [Ecosystem]

- Use cases: share “strategy feature packs” across model families; certify features for domains.

- Tools/workflows: ONNX-like format for control vectors/SAE dictionaries; registries with metadata, benchmarks, and licenses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: layer/embedding alignment across models; IP and safety governance.

- Multimodal strategy control (vision, speech, code) [Multimodal AI]

- Use cases: enforce verification on chart/image interpretations; hypothesis testing with audio transcripts; plan-first code generation paired with tests.

- Tools/workflows: multimodal SAEs; modality-bridged feature routing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: new training procedures for multimodal features; compute and data scale.

- Cost-effective test-time compute governance [Platform/Infra]

- Use cases: trade off CoT length vs accuracy by routing strategies; avoid over/underthinking pathologies.

- Tools/workflows: budget-aware routers that select strategies to meet latency/accuracy SLAs; dynamic α/T scheduling.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable performance curves per task; production-grade telemetry.

- Legal and policy frameworks for auditable “steered reasoning” [Public Policy/Standards]

- Use cases: require reasoning policy disclosure and audit logs in critical deployments; certify conformance to strategy controls.

- Tools/workflows: compliance checkers; standardized reporting of strategy usage; third-party audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consensus on privacy of internal activations/CoT; harmonization across jurisdictions.

Notes on feasibility common to many applications:

- Access: Closed-source APIs generally don’t expose internal activations; deployment favors open/self-hosted models.

- Portability: SAEs must be trained per model and (often) per layer; cross-domain performance is promising but not guaranteed.

- Tuning: Steering strength (α), duration (T), and layer choice are task-dependent; guardrails needed to prevent repetition or derailment.

- Evaluation: LLM judges are helpful but imperfect; mission-critical setups need human adjudication and robust metrics.

- Safety/Privacy: Strategy logs and activation traces may encode sensitive data; enforce strict data governance.

These applications collectively illustrate how SAE-Steering can mature into a “reasoning governance” layer that enforces, audits, and optimizes how models think, not just what they say.

Glossary

- Activation-based methods: Techniques that control model behavior by directly modifying hidden state activations during generation. "Activation-based methods offer more direct control by deriving a control vector to modify the LRM's hidden states during generation~\citep{SteeringVector_ICLR}."

- Autoregressive setting: A generation framework where each next token is predicted conditioned on previously generated tokens. "In a standard autoregressive setting, an LRM generates the next token based on the prefix ."

- Budget Forcing: An inference-time technique that extends the reasoning process (often by inserting a special token) to encourage additional thinking. "Following Budget Forcing~\citep{s1}, we insert a “wait” token at the end of the initial, flawed reasoning to induce further thinking."

- Chain-of-Thoughts (CoTs): Explicit sequences of intermediate reasoning steps generated before the final answer. "During inference, LRMs produce long Chains-of-Thoughts (CoTs) that explore diverse reasoning paths while continuously verifying previous steps~\citep{marjanoviÄ2025deepseekr1thoughtologyletsthink}."

- Concept entanglement: The mixing of multiple concepts within a single representation or vector, making precise control difficult. "As a result, the derived control vectors are prone to concept entanglement~\citep{entangle1,entangle2}, inadvertently capturing features of multiple strategies and hindering precise control."

- Contrastive pairs: Pairs of examples that differ in the presence or absence of a target behavior, used to compute activation differences. "This control vector is typically computed as activation differences between contrastive pairs exhibiting or lacking a target behavior~\citep{resong_strength2}."

- Control vector: A vector injected into model activations to steer generation toward a desired behavior. "Using the identified strategy-specific features as control vectors, SAE-Steering outperforms existing methods by over 15\% in control effectiveness."

- Disentangled feature space: A representation in which learned features correspond to distinct, non-overlapping concepts. "a well-trained SAE projects the low-dimensional, strategy-entangled hidden states of an LRM into a high-dimensional, disentangled feature space."

- Large Reasoning Models (LRMs): LLMs optimized to perform extended, structured reasoning during inference. "Large Reasoning Models (LRMs), such as GPT-o1~\citep{openai2025o3mini} and DeepSeek-R1~\citep{guo2025deepseek}, employ a “think-then-answer” paradigm"

- LLM judge: A LLM used to evaluate whether generated text exhibits a target behavior or strategy. "An LLM judge then assesses whether more explicitly demonstrates the target strategy than "

- Logit Boosting: A method that directly increases the logits of selected tokens to bias the model’s output. "Logit Boosting, which directly boosts the logits of strategy-specific keywords;"

- Logit contribution matrix: A matrix quantifying each feature’s additive effect on logits for all tokens in the vocabulary. "We compute the logit contribution matrix for all features via:"

- Logit lens: A technique for estimating token logits directly from intermediate activations. "Next, we estimate all SAE features' potential logit contribution to strategy keywords using logit lens~\citep{logitlens}."

- Monosemanticity: The property that a single learned feature corresponds to one interpretable concept. "A key benefit of this decomposition is that the sparsity objective encourages monosemanticity~\citep{claudeTowards}:"

- Residual stream activations: The internal representation vectors passed along the transformer layers’ residual pathways. "producing a sequence of residual stream activations ."

- SAE-Steering: A two-stage pipeline that identifies and applies SAE-derived features to steer reasoning strategies. "we propose SAE-Steering, an efficient two-stage feature identification pipeline."

- Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs): Autoencoders trained with sparsity constraints to learn interpretable, sparse latent features of activations. "we leverage Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) to decompose strategy-entangled hidden states into a disentangled feature space."

- Steering strength: The scalar coefficient controlling how strongly a control vector is injected into activations. "where is the steering strength."

- Strategy router: A component that selects which reasoning strategy to apply during error correction or control. "To select the most appropriate strategy for different problems, we train a strategy router (Appendix~\ref{app:router})."

- Strategy-specific features: SAE-derived latent directions associated with particular reasoning strategies. "identifying the few strategy-specific features from the vast pool of SAE features"

- Think-then-answer paradigm: An inference approach where the model first generates intermediate reasoning steps, then provides the final answer. "employ a “think-then-answer” paradigm, explicitly generating intermediate reasoning processes before deriving final answers."

- Top-K activation function: A sparsity-inducing nonlinearity that keeps only the K largest activations and zeroes the rest. "We enforce sparsity via a Top- activation function, which only retains the largest activation values and sets the rest to zero, following~\cite{TopK}."

- Unembedding matrix: The final linear mapping from hidden activations to vocabulary logits (often called the LM head weights). "let be the LRM's unembedding matrix (i.e., the weight matrix of the LM head)"

- Vector Steering: An activation-based approach that derives control vectors from contrastive activation analysis to steer behavior. "Vector Steering~\citep{SteeringVector_ICLR}, which uses an LLM to annotate reasoning strategies for constructing contrastive datasets, then extracts control vectors via contrast pairs."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.