Coupling Experts and Routers in Mixture-of-Experts via an Auxiliary Loss

Abstract: Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models lack explicit constraints to ensure the router's decisions align well with the experts' capabilities, which ultimately limits model performance. To address this, we propose expert-router coupling (ERC) loss, a lightweight auxiliary loss that tightly couples the router's decisions with expert capabilities. Our approach treats each expert's router embedding as a proxy token for the tokens assigned to that expert, and feeds perturbed router embeddings through the experts to obtain internal activations. The ERC loss enforces two constraints on these activations: (1) Each expert must exhibit higher activation for its own proxy token than for the proxy tokens of any other expert. (2) Each proxy token must elicit stronger activation from its corresponding expert than from any other expert. These constraints jointly ensure that each router embedding faithfully represents its corresponding expert's capability, while each expert specializes in processing the tokens actually routed to it. The ERC loss is computationally efficient, operating only on n2 activations, where n is the number of experts. This represents a fixed cost independent of batch size, unlike prior coupling methods that scale with the number of tokens (often millions per batch). Through pre-training MoE-LLMs ranging from 3B to 15B parameters and extensive analysis on trillions of tokens, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the ERC loss. Moreover, the ERC loss offers flexible control and quantitative tracking of expert specialization levels during training, providing valuable insights into MoEs.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about making a special kind of AI model, called a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE), work better. An MoE is like a team of many mini-experts, each good at certain tasks. A “router” decides which experts should handle each piece of text. The problem is that the router doesn’t always understand what each expert is truly good at, so it sometimes sends tokens (pieces of text) to the wrong experts. The authors introduce a simple extra training signal, called the Expert-Router Coupling (ERC) loss, to help the router and experts “sync up” and cooperate better.

What did the researchers want to find out?

In simple terms, they asked:

- Can we help the router learn what each expert is actually good at, so it sends the right tokens to the right experts?

- Can we do this without slowing training or using a lot more memory?

- Can we control and measure how “specialized” each expert becomes, and see how that affects performance?

How did they do it? (Methods in simple terms)

Think of an MoE like a hospital:

- There are many doctors (experts).

- A receptionist (router) decides which doctor a patient (token) should see.

- If the receptionist doesn’t understand each doctor’s strengths, patients might be sent to the wrong doctor.

The authors add a lightweight training trick (ERC loss) so the receptionist and doctors learn to match each other.

Key idea: Give each expert a “proxy token” and check who responds strongest

- Each expert has a special vector (a list of numbers) inside the router called a router embedding. The authors treat each embedding like a “proxy token” that represents the kind of tokens usually sent to that expert—like a label for that expert’s patient group.

- They add a tiny bit of safe randomness to each proxy (like gently shaking it) so it represents not just one exact point, but a small neighborhood of similar tokens. This randomness is carefully limited so the proxy stays in its own “group” and doesn’t drift into another expert’s area.

Measure “who lights up most”

- They pass each proxy token through every expert and measure how strongly each expert “lights up” (the activation norm—think of it like measuring the brightness of a light bulb).

- This creates a small table (where is the number of experts) showing, for every proxy, which expert reacts most.

Add two simple rules (the ERC loss)

The ERC loss encourages two things:

- Expert i should react most to its own proxy (so the expert specializes in its own tokens).

- Proxy i should get its strongest reaction from expert i (so the router’s embedding really matches what expert i can do).

A single parameter, , controls how strict this is. Smaller means “be more picky” (stronger specialization). Bigger means “it’s okay if experts are a bit similar.”

Why this is efficient

- The extra work only depends on the number of experts, not the number of tokens. It uses about extra “checks,” which is tiny compared to training on millions of tokens per batch.

- It adds almost no slowdown during training and no overhead at all during inference (model use).

What did they find?

- Models trained with ERC loss are more accurate than standard MoE models across many benchmarks.

- ERC keeps training fast and memory-friendly—almost the same speed as regular MoEs, and much faster than previous “dense activation” methods that check many experts per token.

- It works at different sizes, from 3 billion to 15 billion parameters, and improves scores on tough tests like MMLU.

- ERC helps experts become meaningfully specialized. The authors can also:

- Tune specialization with (like a dial from “generalist” to “specialist”).

- Track specialization with a measured noise bound (called ), which decreases when experts become more similar.

- There’s a trade-off: too much specialization can hurt performance. The best setting depends on how many experts you have and how many you select per token.

Why does this matter?

- Better routing means the right expert handles the right token, which improves quality without extra cost.

- ERC teaches the router what experts can actually do, instead of letting it guess through trial and error.

- The method scales well, making it practical for LLMs.

- It also gives researchers and engineers a simple “control knob” () and a “thermometer” () to manage and measure expert specialization, leading to clearer insights and better models.

Takeaway and impact

This work shows a simple, efficient way to make MoE models smarter by tightly connecting routers and experts. It boosts accuracy, keeps training affordable, and offers tools to study and tune how specialized experts should be. In practice, this can help build faster, more capable LLMs that make better use of their many expert parts—useful for everything from chatbots to tutoring systems to code assistants.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper. Each item is framed to be concrete and actionable for future work.

- Lack of formal theory: Provide a rigorous justification that intermediate activation norms reliably measure “capability alignment” across diverse architectures and training regimes (beyond empirical inspiration), including conditions under which norm-based coupling is provably sound or fails.

- Assumption on router embeddings: Test and analyze the impact when router embedding rows have non-comparable norms (the paper assumes comparable norms). Quantify how deviations affect clustering fidelity, proxy-token validity, and ERC effectiveness.

- Proxy token design: Compare multiplicative vs additive noise, and different noise distributions (e.g., Gaussian, dropout-style masks). Assess whether the current bound on remains appropriate when gating uses inner products and softmax rather than Euclidean nearest-centers assumptions.

- Coupling stage choice: Evaluate ERC computed at different expert stages (e.g., after or , or full expert forward) to test whether coupling via alone is optimal. Quantify trade-offs between fidelity to “expert capability” and added compute.

- Scalability to very large : Benchmark ERC’s activation measurements for (e.g., thousands of experts). Identify thresholds where the fixed cost becomes non-negligible and explore approximations (e.g., blockwise coupling, low-rank sketches, sampling).

- Interaction with : Systematically study how ERC interacts with different top- values, including very small or dynamic , and characterize the specialization–collaboration trade-off across pairs.

- Automated selection: Develop and test principled schedules or adaptation rules for based on training signals (e.g., specialization metrics, load balancing, validation performance), rather than manual grid search.

- ERC loss weight: Explore varying the ERC loss weight (currently fixed at 1), including annealing strategies, per-layer weights, or adaptive balancing against the main objective and load-balancing loss.

- Specialization metrics: Define and validate quantitative, model-agnostic specialization metrics beyond (e.g., token–expert mutual information, routing purity, inter-expert confusion), and correlate them with downstream performance.

- Token-level routing quality: Directly measure whether ERC reduces misrouting (e.g., via oracle expert assignment or AoE-style dense probing on a sampled subset) and quantify improvements in routing precision/recall.

- Robustness and distribution shift: Evaluate ERC under domain shifts (e.g., new datasets, multilingual inputs, long-context tasks) and adversarial or noisy tokens to determine whether coupling overfits router–expert relations to pretraining domains.

- Generalization to other MoE components: Test ERC with attention experts, shared experts, expert parameter sharing, and alternative FFN activations (ReLU, GELU) to establish breadth of applicability.

- Capacity and load balancing: Investigate ERC’s interaction with capacity constraints (as in Switch Transformers) and alternative load-balancing formulations. Measure whether ERC mitigates “dead” or “hot” experts across training.

- Communication and parallelism: Provide detailed analysis of ERC’s impact on distributed training (expert/data/model parallel), including communication overhead and memory footprint in heterogeneous hardware settings.

- Inference-time behavior: Examine whether ERC-trained models exhibit improved routing calibration, stability, and latency under inference-time constraints (e.g., speculative decoding, caching, KV-sharing).

- Language and task breadth: Extend evaluation beyond mainly English benchmarks to multilingual, code, reasoning with tool use, and generative metrics (e.g., perplexity, BLEU, factuality) to test generality of gains.

- Perplexity and pretraining signals: Report intrinsic LM metrics (perplexity, loss curves) to confirm that downstream gains are accompanied by core modeling improvements, and analyze when gains appear during training.

- Comparisons to more baselines: Include efficiency-aware coupling baselines (e.g., contrastive losses on gated subsets, router–expert co-training variants) to contextualize ERC’s improvements relative to non-dense alternatives.

- Degenerate solutions analysis: Provide theoretical and empirical safeguards against trivial norm manipulation (e.g., scaling ) beyond appendix ablations—prove or bound that ERC minima correspond to meaningful coupling.

- Layer-wise effects: Study where ERC is most beneficial (early vs middle vs late MoE layers), and whether selective application reduces compute while preserving gains.

- Curriculum and scheduling: Test curricula that introduce ERC progressively (e.g., warm-up without ERC; gradual tightening of ), and evaluate stability benefits or performance trade-offs.

- Data dependence: Quantify how ERC behaves across different pretraining mixtures (e.g., proportions of code/math/web), and whether certain domains require different or noise bounds.

- Extreme specialization risks: Characterize failure modes when is too low (e.g., over-fragmentation, brittle routing, reduced compositionality), and propose diagnostics/mitigations.

- The role of geometry: Explore alternative router embedding geometries (e.g., spherical/orthogonal constraints, temperature-scaled logits) and evaluate whether geometric regularizations complement or substitute ERC.

- Downstream fine-tuning: Assess whether ERC benefits persist or change after instruction tuning, RLHF, or task-specific fine-tuning, including stability and catastrophic forgetting.

- Token capacity and latency under high load: Analyze ERC’s behavior under high-traffic tokens or capacity overflow events—does tighter coupling worsen contention or improve graceful degradation?

- Privacy and safety: Investigate whether tighter expert–router coupling affects memorization, privacy leakage, or safety behavior, and whether specialization concentrates sensitive patterns in specific experts.

- Reproducibility details: Provide seeds, full training curves, and release code/models to enable independent validation of ERC’s efficiency and accuracy claims across compute budgets.

Glossary

- Activation norm: The magnitude of an intermediate layer’s activation, used as a signal for how well an expert matches a token. "the intermediate activation norm serves as an indicator of how well its capabilities align with the token."

- Autonomy-of-Experts (AoE): An MoE variant that encodes routing into expert parameters and selects experts via their activation norms. "Autonomy-of-Experts (AoE;~\citealp{lv2025autonomyofexperts}) encodes the routing function into expert parameters."

- Cluster centers: The router’s parameter rows interpreted as centers of token clusters routed to each expert. "router parameters are viewed as cluster centers."

- Contrastive learning: A training paradigm that encourages separation between representations; the paper’s constraints resemble contrastive objectives. "Constraints~\ref{eq:row-loss} and \ref{eq:column-loss} bear similarity to contrastive learning~\citep{chen2020simpleframeworkcontrastivelearning,oord2019representationlearningcontrastivepredictive,NEURIPS2020_d89a66c7}."

- Cosine similarity: A vector similarity metric used in specialization losses; computing it per token can be expensive. "reducing expert overlap but incurring high cost due to cosine similarity calculations per token."

- Denser activation: Activating many experts or layers during training, increasing compute and memory cost. "they incur substantial computational and memory costs due to denser activation."

- Expert-router coupling (ERC) loss: The proposed auxiliary loss that aligns router decisions with expert capabilities using proxy tokens and activation constraints. "we propose expert-router coupling (ERC) loss, a lightweight auxiliary loss that tightly couples the router's decisions with expert capabilities."

- Expert specialization: The degree to which experts develop distinct capabilities for specific token clusters. "Moreover, the ERC loss offers flexible control and quantitative tracking of expert specialization levels during training, providing valuable insights into MoEs."

- Factorization rank (r): The rank used in AoE’s low-rank factorization of expert parameters for norm-based routing. "AoE factorizes into two -rank matrices and ."

- FLOPs: A measure of computational cost in floating-point operations used to analyze training efficiency. "expert-router coupling loss\ introduces only additional FLOPs, a cost that is negligible in practical pre-training setups where is often in the millions."

- Gating network z-loss: An auxiliary loss that penalizes large router logits to stabilize MoE training. "\citet{stmoe} introduced the z-loss, which penalizes excessively large logits in the gating network to enable stable training."

- LLMs: High-parameter neural LLMs that often use MoE architectures. "Mixture-of-Experts (MoE, \citealp{shazeer2017,fedus2022switchtransformersscalingtrillion,lepikhin2021gshard,stmoe}) is a core architecture in modern LLMs."

- Load balancing loss: An auxiliary loss that encourages even distribution of tokens across experts. "A load balancing loss~\citep{fedus2022switchtransformersscalingtrillion} with a weight of 0.01 is applied consistently in all experiments."

- Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): An architecture that routes tokens to a subset of specialized experts via a router for efficient scaling. "Mixture-of-Experts (MoE, \citealp{shazeer2017,fedus2022switchtransformersscalingtrillion,lepikhin2021gshard,stmoe}) is a core architecture in modern LLMs."

- Multiplicative random noise: Bounded multiplicative perturbations applied to router embeddings to form proxy tokens while staying within clusters. "$\boldsymbol{\delta}_i \in \mathbbm{R}^{d}$ is bounded multiplicative random noise, which we elaborate in \S\ref{sec:noise}."

- Norm-based selection: Selecting experts based on the magnitude of intermediate activations as a proxy for match quality. "This norm-based selection is justified by the fact that the activation norm of MLPs represents how well their capabilities match their inputs~\citep{geva-etal-2021-transformer,dejavu}."

- Orthogonality (router embeddings): Encouraging router embeddings to be orthogonal; the paper argues this is only weakly tied to specialization. "orthogonality among router embeddings~\cite{ernie} is only weakly correlated with specialization, since the router and experts are typically decoupled."

- Proxy token: A perturbed router embedding used as a stand-in for the tokens assigned to an expert to probe activations efficiently. "Our approach treats each expert's router embedding as a proxy token for the tokens assigned to that expert, and feeds perturbed router embeddings through the experts to obtain internal activations."

- Router: A linear classifier that decides which experts process each token in an MoE layer. "A linear classifier, known as the ``router,'' selects which experts process each input token."

- Router embedding: The learnable per-expert vectors in the router parameter matrix that act as cluster centers and proxies. "orthogonality among router embeddings~\cite{ernie} is only weakly correlated with specialization, since the router and experts are typically decoupled."

- Router logits: The unnormalized scores produced by the router before softmax, which can be supervised or regularized. "\citet{pham2024competesmoe} use experts' final output norms to supervise router logits."

- SiLU: An activation function (Sigmoid Linear Unit) used within expert MLPs. "E_{i}() = \left(\text{SiLU}({i}_{g}) \odot ( {i}_{p})\right) {i}_{o},"

- Sparsity: The practice of activating only a subset of experts to reduce compute, central to MoE efficiency. "There is no inference overhead but the model is fully dense-activated during training, contradicting the core sparsity principle of MoE."

- SwiGLU: A gated MLP variant commonly used in LLMs, combining gating and activation to improve performance. "Our description follows the prevailing SwiGLU structure used by advanced LLMs~\citep{qwen25,deepseekai2025deepseekv3technicalreport,openai_gptoss_2025}."

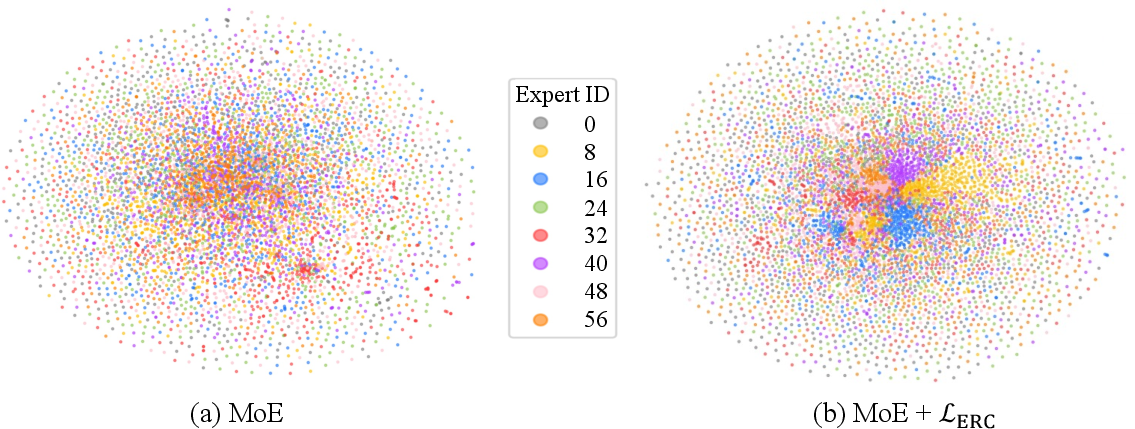

- t-SNE: A dimensionality-reduction technique for visualizing high-dimensional expert parameters. "we use t-SNE~\citep{tsne} to project each row of (where ) from layer 6 (the middle depth) onto a 2D point."

- Top-K: The selection of the K experts with the highest router scores to process a token. "Typically, the top- experts with the highest expert weights are selected to process the token."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now by organizations that train or fine-tune Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) LLMs, with minimal engineering and compute risk given the paper’s demonstrated efficiency and stability.

- MoE training upgrade for LLM providers (software/AI)

- Replace or augment existing MoE pretraining with the ERC auxiliary loss to improve downstream accuracy without adding inference cost.

- Potential product/workflow: an

ERC-Lossplugin for training stacks (e.g., OLMoE, HuggingFace Transformers, Megatron-LM), plus a turnkey training recipe. - Assumptions/dependencies: existing MoE architecture with routers and top-K gating; acceptance that intermediate activation norms correlate with expert–token match quality; modest integration effort to compute the activation matrix per MoE layer.

- Cost-efficient alternative to dense coupling methods (software/AI, energy)

- Replace Autonomy-of-Experts (AoE) or dense-activation guidance methods with ERC to reduce training hours and memory while retaining (or approaching) performance improvements.

- Potential workflow: “MoE coupling mode” flag to switch between ERC and legacy methods; training dashboards showing throughput gains and memory headroom.

- Assumptions/dependencies: ERC’s measured overhead (≈0.2–0.8%); not too small (benefits are larger with moderate-to-large expert counts).

- Fine-tuning existing MoE models for better routing (software/AI)

- Apply ERC during continued pretraining or task-specific fine-tuning to tighten router–expert alignment and reduce misrouting that suppresses specialization.

- Potential tool:

erc_finetune()utility that adds loss terms and schedules . - Assumptions/dependencies: access to model weights and training loop; the router embeddings must be trainable (not frozen).

- Specialization control and monitoring for research and MLOps (academia, software/AI)

- Use to control specialization degree and (noise bound) to quantify specialization dynamics across training runs.

- Potential product: “Expert Specialization Dashboard” that tracks cluster center distances, , and ERC loss per layer over time.

- Assumptions/dependencies: logging infrastructure (e.g., Weights & Biases); acceptance of as a proxy for specialization; consistent norm scaling of router embeddings.

- Stable MoE load balancing with coupling (software/AI)

- Combine ERC with standard load balancing losses to keep token distribution equitable while improving routing fidelity.

- Potential workflow: training configuration template that co-tunes load balancing coefficients and ERC .

- Assumptions/dependencies: current load balancing setup; ERC does not materially disrupt load balancing (empirically negligible difference).

- Domain-optimized expert design (healthcare, finance, education, legal)

- Train domain-specialized experts (e.g., clinical reasoning, regulatory compliance, pedagogical tutoring) and use ERC to ensure routers actually route relevant tokens to those experts.

- Potential product: “Domain-Coupled MoE” variants for verticals (e.g., clinical LLM, risk/compliance LLM).

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain data availability; careful selection of and to ensure an effective -expert set for typical inputs.

- Benchmarking and model selection improvements (academia, software/AI)

- Use ERC-augmented MoEs to achieve stronger scores on public benchmarks (MMLU, BBH, GSM8K, TriviaQA) with negligible inference cost.

- Potential workflow: standardized evaluation suite comparing vanilla MoE vs ERC MoE during model selection.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reproducible training conditions; adherence to the paper’s hyperparameter schedule or modest tuning.

- Energy/carbon-aware model training (policy, energy)

- Leverage ERC’s fixed-cost coupling (independent of batch size) to lower the training energy footprint compared to dense coupling methods.

- Potential tool: emissions estimator integrated into training pipelines to report gains from ERC adoption.

- Assumptions/dependencies: accurate power measurement; comparable training objectives and datasets.

- Router–expert health audits (software/AI, safety)

- Run periodic ERC diagnostics (activation matrices, off-diagonal penalties) to detect degenerate or overlapping experts and misaligned router embeddings during training.

- Potential product: “MoE Coupling Auditor” with automated alerts when coupling deteriorates.

- Assumptions/dependencies: ERC loss instrumentation; thresholds calibrated to model size and .

- Education and tutoring LLMs with structured expert assignments (education)

- Build curriculum-aligned experts (math reasoning, reading comprehension, science) and use ERC to enforce specialization so students get reliably routed assistance.

- Potential product: “ERC-Coupled Tutor” with trackable specialization metrics per subject area.

- Assumptions/dependencies: labeled or curated educational corpora; appropriate for breadth of subjects.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, larger-scale validation, productization, or ecosystem changes (e.g., standardization, hardware, policy frameworks).

- Automated scheduling and specialization auto-tuning (software/AI, academia)

- Develop AutoML/RL methods that adapt per layer and training phase to optimize the specialization–collaboration trade-off.

- Potential product: “ERC-Alpha AutoTune” that searches for a given configuration.

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable specialization metrics; generalizable policies across model scales and domains.

- Standardized specialization metrics and benchmarks (academia, policy)

- Establish community metrics using , cluster distances, and activation matrices as a standard to evaluate specialization claims across MoEs.

- Potential workflow: a public benchmark suite and reporting protocol for specialization under different , dataset regimes, and loss weights.

- Assumptions/dependencies: consensus on metric validity; multi-institution replication.

- Cross-modal MoE coupling (vision, speech, robotics)

- Extend ERC to multimodal MoEs (vision-language, speech-language, planning-language) to improve gating fidelity across modality-specific experts.

- Potential product: “ERC-Multimodal MoE” for assistive robotics or AR systems with specialized perception and language experts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: analogous activation-norm indicators in non-text MLPs; router design that accommodates multimodal embeddings.

- Personalization via user-specific or cohort experts (daily life, software/AI)

- Train cohort or user-level experts (e.g., writing style, domain familiarity) and apply ERC to ensure consistent routing for personalized experiences.

- Potential product: “Personalized ERC-MoE” with privacy-preserving on-device fine-tuning of router embeddings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: privacy and data governance; efficient expert proliferation and routing stability for large .

- Multi-tenant MoE serving with coupled routing (software/AI, enterprise)

- Host multiple tenant-specific experts inside a shared MoE and use ERC to guarantee tenant isolation at the routing level.

- Potential product: “Tenant-Isolated MoE” offering SLAs for cross-expert interference.

- Assumptions/dependencies: tenancy-aware router design; robust monitoring and arbitration policies.

- Hardware–software co-design for ERC-aware MoEs (energy, hardware)

- Architect accelerators that exploit ERC’s fixed coupling workload to precompute activation norms and optimize memory layouts for experts.

- Potential product: “ERC-ready” kernels and compiler passes that fuse proxy activation computations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: vendor support; stable ERC workload characteristics across models.

- Safety and reliability frameworks leveraging coupling metrics (policy, safety)

- Use ERC-derived coupling health signals to detect training pathologies (mode collapse, expert drift) and enforce safety gates or retraining triggers.

- Potential workflow: safety audits that include coupling integrity checks alongside bias and robustness tests.

- Assumptions/dependencies: validated correlations between coupling integrity and safety outcomes; governance processes to act on alerts.

- Dynamic expert pool sizing and routing policies (software/AI)

- Learn to adjust and over training or per domain, with ERC maintaining coupling fidelity amid structural changes.

- Potential product: “Elastic MoE” systems that scale experts up/down based on workload and domain demands.

- Assumptions/dependencies: stable reconfiguration procedures; resilience of routers to topology changes.

- Sector-specific ERC recipes at very large scales (healthcare, finance, legal)

- Validate ERC in 70B–>trillion-parameter MoEs on regulated domains, codifying best practices for , expert layouts, and coupling strength.

- Potential product: “Regulated-Domain ERC Playbooks” with compliance-mapped training and evaluation protocols.

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to high-quality, compliant datasets; large-scale compute; domain expert oversight.

- Curriculum/data shaping for specialization (academia, software/AI)

- Co-design datasets and curricula that intentionally sculpt expert niches, using ERC metrics to measure achieved specialization.

- Potential workflow: data schedulers that shift sampling distributions as coupling improves.

- Assumptions/dependencies: proven links between data distribution and specialization; tooling to measure and react in training.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.